Impact of Digital Capabilities on Digital Transformation: The Mediating Role of Digital Citizenship

Abstract

1. Introduction

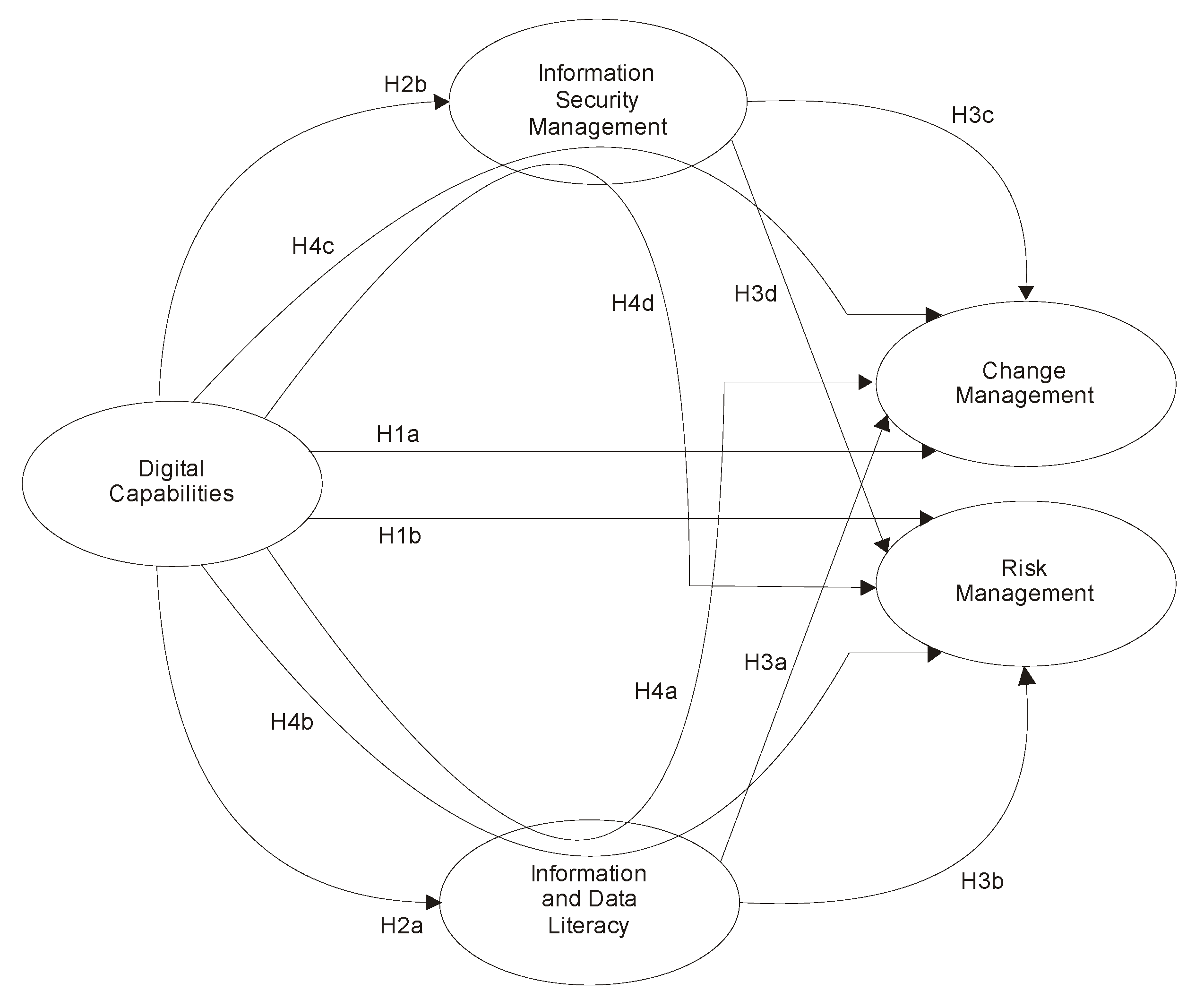

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling

3.2. Measurements

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

4.2. Structural Model Assessment

5. Discussion

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research Direction

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bharadwaj, A.; El Sawy, O.A.; Pavlou, P.A.; Venkatraman, N.V. Digital business strategy: Toward a next generation of insights. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas Junior, J.C.; Maçada, A.C.; Brinkhues, R.; Montesdioca, G. Digital Capabilities as Driver to Digital Business Performance, Twenty-Second Americas Conference on Information Systems. In Proceedings of the 22nd Americas Conference on Information Systems, AMCIS 2016, San Diego, CA, USA, 11–14 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liere-Netheler, K.; Packmohr, S.; Vogelsang, K. Drivers of Digital Transformation in Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hilton Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2018; pp. 3926–3935. [Google Scholar]

- Tangi, L.; Janssen, M.; Benedetti, M.; Noci, G. Barriers and Drivers of Digital Transformation in Public Organizations: Results from a Survey in the Netherlands. In Electronic Government; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mačiulienė, M. Mapping digital co-creation for urban communities and public places. Systems 2018, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, T.; Tomidei, L.; Trianni, A. Towards a Novel Framework of Barriers and Drivers for Digital Transformation in Industrial Supply Chains. In Proceedings of the 2019 Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology (PICMET), Portland, OR, USA, 25–29 August 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Solberg, E.; Traavik, L.E.; Wong, S.I. Digital mindsets: Recognizing and leveraging individual beliefs for digital transformation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2020, 62, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Cuddy, A.J.; Glick, P. Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007, 11, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. Rev. 2019, 28, 13–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousopoulou, E.; Kamariotou, M.; Kitsios, F. Digital transformation strategy in post-COVID era: Innovation performance determinants and digital capabilities in driving schools. Information 2022, 13, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, D.; Kraus, P. Skills and competencies for digital transformation–A critical analysis in the context of robotic process automation. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2021, in press. [CrossRef]

- Simić, M.; Slavković, M.; Ognjanović, J. Information Literacy Competencies in Digital Age: Evidence from Small-and Medium-Sized Enterprises. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference EBM 2020, Contemporary Issues in Economics, Business and Management, Faculty of Economics University of, Kragujevac, Kragujevac, The Republic of Serbia, 14 December 2020; pp. 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kayworth, T.; Whitten, D. Effective information security requires a balance of social and technology factors. MIS Q. Exec. 2010, 9, 2012–2052. [Google Scholar]

- Khin, S.; Ho, T.C. Digital technology, digital capability and organizational performance: A mediating role of digital innovation. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2018, 11, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia, J.; Castillo-Vergara, M.; Geldes, C.; Felix, M.; Gamarra, C.; Flores, A.; Heredia, W. How do digital capabilities affect firm performance? The mediating role of technological capabilities in the “new normal”. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi Sheykhjan, T. Internet research ethics: Digital Citizenship Education. In Proceedings of the Seminar on New Perspectives in Research. Seminar conducted by Department of Education, University of, Kerala, Kerala, India, 17–18 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, J. Building strong futures: Literacy practices for developing engaged citizenship in the 21st century. Aust. J. Lang. Lit. 2016, 39, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberländer, M.; Beinicke, A.; Bipp, T. Digital competencies: A review of the literature and application in the workplace. Comput. Educ. 2019, 146, 103752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, E.; Simsek, A. New literacies for digital citizenship. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2013, 4, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jæger, B. Digital Citizenship—A Review of the Academic Literature. Dms Der Mod. Staat Z. Für Public Policy Recht Und Manag. 2021, 14, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. Outsourcing, new technologies and new technology risks: Current and trending UK regulatory themes, concerns and focuses. J. Secur. Oper. Custody 2018, 10, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Fingal, J.; The 5 Competencies of Digital Citizenship. Int. Soc. Technol. Education. 2019. Available online: https://www.iste.org/explore/digitalcitizenship/5-competenciesdigital-citizenship (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Shelley, M.; Thrane, L.; Shulman, S.; Lang, E.; Beisser, S.; Larson, T.; Mutiti, J. Digital Citizenship: Parameters of the Digital Divide. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2004, 22, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribble, M.; Miller, T.N. Educational leadership in an online world: Connecting students to technology responsibly, safely, and ethically. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 2013, 17, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmundsen, K.; Iden, J.; Bygstad, B. Digital Transformation: Drivers, Success Factors, and Implications. In Proceedings of the 12th Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems (MCIS), Corfu, Greece, 28–30 September 2018; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. A Policy Review: Building Digital Citizenship in Asia Pacific Through Safe, Effective and Responsible Use of ICT; UNESCO Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education: Bangkok, Thailand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Legner, C.; Eymann, T.; Hess, T.; Matt, C.; Böhmann, T.; Drews, P.; Mädche, A.; Urbach, N.; Ahlemann, F. Digitalization: Opportunity and Challenge for the Business and Information Systems Engineering Community. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2017, 59, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, N.; Sasanti, N.; Alamsjah, F.; Sadeli, F. Strategic role of digital capability on business agility during COVID-19 era. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 197, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopik, J.; Jahn, C.; Schuster, T.; Hoßbach, N.; Pflaum, A. Mastering the digital transformation through organizational capabilities: A conceptual framework. Digit. Bus. 2022, 2, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenkova, V.; Keranova, D.; Peicheva, D. Digital Skills, New Media and Information Literacy as a Conditions of Digitization. In Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics (AHFEE 2019); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Prasetiyo, W.H.; Naidu, N.B.M.; Tan, B.P.; Sumardjoko, B. Digital Citizenship Trend in Educational Sphere: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2021, 10, 1192–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahne, J.; Bowyer, B. Can media literacy education increase digital engagement in politics? Learn. Media Technol. 2019, 44, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, H.T.; Chen, J.S. How does digital technology usage benefit firm performance? Digital transformation strategy and organisational innovation as mediators. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Hu, J. ICT self-efficacy and ICT interest mediate the gender differences in digital reading: A multilevel serial mediation analysis. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2022, 17, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Feng, B. Digital inequality in online reciprocity between generations: A preliminary exploration of ability to use communication technology as a mediator. Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebel, T.M. Digital Transformation: Survive and Thrive in an Era of Mass Extinction; RosettaBooks: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rupeika-Apoga, R.; Petrovska, K.; Bule, L. The Effect of Digital Orientation and Digital Capability on Digital Transformation of SMEs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament; Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union; Hadzhieva, E. Impact of Digitalisation on International Tax Matters: Challenges and Remedies, European Parliament. 2019. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2861/694173 (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Zangiacomi, A.; Pessot, E.; Fornasiero, R.; Bertetti, M.; Sacco, M. Moving towards digitalization: A multiple case study in manufacturing. Prod. Plan. Control. 2020, 31, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- e-CF. European e-Competence Framework. 2016. Available online: http://ecompetences.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/European-e-CompetenceFramework-3.0_CEN_CWA_16234–1_2014.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Jansson, J.; Andervin, M. Leading Digital Transformation; DigJourney Publishing: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt, J.M.; Creasey, T.J. Change Management: The People Side of Change. Prosci Inc.: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jägare, V.; Karim, R.; Söderholm, P.; Larsson-Kråik, P.O.; Juntti, U. Change Management in Digitalised Operation and Maintenance of Railway. In Proceedings of the International Heavy Haul Association (IHHA) STS 2019, Narvik, Norway, 10–14 June 2019; pp. 904–911. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.; King, D.; Sidhu, R.; Skelsey, D. (Eds.) The Effective Change Manager’s Handbook: Essential Guidance to the Change Management Body of Knowledge; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Raju, V. Implementing flexible systems in doctoral viva defense through virtual mechanism. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2021, 22, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnasse, F.; Menzefricke, J.S.; Dumitrescu, R. Identification of Socio-Technical Risks and Their Correlations in the Context of Digital Transformation for the Manufacturing Sector. In Proceedings of the IEEE 8th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Applications (ICIEA), Virtual, 23–26 April 2021; pp. 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Yeow, A.; Soh, C.; Hansen, R. Aligning with new digital strategy: A dynamic capabilities approach. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2018, 27, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkhipova, D.; Bozzoli, C. Digital Capabilities. In CIOs and the Digital Transformation; Bongiorno, G., Rizzo, D., Vaia, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vătămănescu, E.M.; Andrei, A.G.; Gazzola, P.; Dominici, G. Online academic networks as knowledge brokers: The mediating role of organizational support. Systems 2018, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesböck, F.; Hess, T. Digital innovations. Electron Mark 2019, 30, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürstenau, D.; Cleophas, C.; Kliewer, N. How do market standards inhibit the enactment of digital capabilities? Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2020, 62, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, F. ‘Developing digital skills and literacies in UK higher education: Recent developments and a case study of the Digital Literacies Framework at the Univ. of Brighton’ Publicaciones 2018, 48, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeyer, X.; Santos, S.C.; Morris, M.H. Overcoming Barriers to Technology Adoption When Fostering Entrepreneurship Among the Poor: The Role of Technology and Digital Literacy. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 68, 1605–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Briel, F.; Recker, J.; Davidsson, P. Not all digital venture ideas are created equal: Implications for venture creation processes. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2018, 27, 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.; Gonsalves, E. Organizational learning and entrepreneurial strategy. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2002, 3, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcary, M.; Doherty, E.; Conway, G. A Dynamic Capability Approach to Digital Transformation: A Focus on Key Foundational Themes. In The European Conference on Information Systems Management; Academic Conferences International Limited: South Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, C.S. Information Literacy in an Information Society: A Concept for the Information Age; Diane Publishing: Darby, PA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pangrazio, L.; Selwyn, N. ‘Personal data literacies’: A critical literacies approach to enhancing understandings of personal digital data. New Media Soc. 2019, 21, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimini, C.; Romero, D.; Pinto, R.; Cavalieri, S. Task Classification Framework and Job-Task Analysis Method for Understanding the Impact of Smart and Digital Technologies on the Operators 4.0 Job Profiles. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellantuono, N.; Nuzzi, A.; Pontrandolfo, P.; Scozzi, B. Digital transformation models for the I4. 0 transition: Lessons from the change management literature. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, M.; Plekhanov, D.; Galindo-Rueda, F.; Ker, D. 7 The digitalisation of science and innovation policy. Digit. Sci. Technol. Innov. 2020, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Lanes, K.L.; Wilson, T.C. Are you paying too much for that acquisition? Harv. Bus. Rev. 1999, 77, 136. Available online: https://hbr.org/1999/07/are-you-paying-too-much-for-that-acquisition (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Coskun, Y.D. Promoting digital change in higher education: Evaluating the curriculum digitalisation. J. Int. Educ. Res. (JIER) 2015, 11, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikse, V.; Lusena-Ezera, I.; Rivza, P.; Rivza, B. The development of digital transformation and relevant competencies for employees in the context of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in latvia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, S.A.; Gammill, S. Irons. Integrating Technology into the Curriculum; Shell Education: Huntington Beach, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rader, H.B. Conference Circuit: Information literacy: The professional issue: Subjects addressed at the Third National Australian Conference. Coll. Res. Libr. News 2019, 59, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Serbia (2023). CCIS Regional Support. Available online: https://kragujevac.pks.rs/strana/rpk-kragujevac-privreda-regiona (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Kock, N.; Hadaya, P. Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 227–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbian Business Registers Agency (2023). Statistics and Info Graphics. Available online: https://www.apr.gov.rs/home.1435.html (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Amankwaa, A.; Gyensare, M.A.; Susomrith, P. Transformational leadership with innovative behaviour: Examining multiple mediating paths with PLS-SEM. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, G.; Bonnet, D.; McAfee, A. Leading Digital: Turning Technology into Business Transformation; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Pieper, T.M.; Ringle, C.M. The use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in strategic management research: A review of past practices and recommendations for future applications. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 320–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hollingsworth, C.L.; Randolph, A.B.; Chong, A.Y.L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGrawHill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. How to Write Up and Report PLS Analysis. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Vinzi, V.E., Chin, W.W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 655–690. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-Validatory Choice and Assessment of Statistical Predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1974, 36, 111–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisser, S. A Predictive Approach to the Random Effects Model. Biometrika 1974, 61, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen, D.J.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Calantone, R.J. Common Beliefs and Reality about Partial Least Squares: Comments on Rönkkö&Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavković, M.; Sretenović, S.; Bugarčić, M. Remote Working for Sustainability of Organization during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediator-Moderator Role of Social Support. Sustainability 2022, 14, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavković, M.; Ognjanović, J.; Bugarčić, M. Sustainability of Human Capital Efficiency in the Hotel Industry: Panel Data Evidence. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099035001132365997/pdf/P1694820bcef0903e091160315d2050d03b.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2022).

| Construct and Item Description | Convergent Validity | VIF | Composite Reliability | α | AVE | Cross-Validated Communality Index (H2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC: Digital Capabilities | 0.914 | 0.886 | 0.639 | 0.490 | |||

| DC01 | 0.792 | 2.331 | |||||

| DC02 | 0.853 | 3.106 | |||||

| DC03 | 0.802 | 2.658 | |||||

| DC04 | 0.856 | 2.945 | |||||

| DC05 | 0.721 | 1.649 | |||||

| DC06 | 0.764 | 1.828 | |||||

| Digital Citizenship | |||||||

| IDL: Information and Data Literacy | 0.926 | 0.904 | 0.677 | 0.528 | |||

| IDL01 | 0.795 | 2.081 | |||||

| IDL02 | 0.801 | 2.363 | |||||

| IDL03 | 0.873 | 2.890 | |||||

| IDL04 | 0.820 | 2.313 | |||||

| IDL05 | 0.811 | 2.531 | |||||

| IDL06 | 0.832 | 2.821 | |||||

| ISM: Information Security Management | 0.908 | 0.798 | 0.832 | 0.423 | |||

| ISM01 | 0.907 | 1.790 | |||||

| ISM02 | 0.918 | 1.790 | |||||

| Digital Transformation | |||||||

| CM: Change Management | 0.882 | 0.822 | 0.653 | 0.422 | |||

| CM01 | 0.757 | 1.715 | |||||

| CM02 | 0.763 | 1.735 | |||||

| CM03 | 0.858 | 2.722 | |||||

| CM04 | 0.849 | 2.652 | |||||

| RM: Risk Management | 0.925 | 0.878 | 0.804 | 0.570 | |||

| RM01 | 0.883 | 2.218 | |||||

| RM02 | 0.905 | 2.547 | |||||

| RM03 | 0.901 | 2.508 | |||||

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CM: Change Management | 0.808 | ||||

| 2. IDL: Information and Data Literacy | 0.612 | 0.823 | |||

| 3. ISM: Information Security Management | 0.581 | 0.679 | 0.912 | ||

| 4. DC: Digital Capabilities | 0.492 | 0.545 | 0.466 | 0.799 | |

| 5. RM: Risk Management | 0.700 | 0.598 | 0.592 | 0.407 | 0.896 |

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CM: Change Management | – | ||||

| 2. IDL: Information and Data Literacy | 0.703 | ||||

| 3. ISM: Information Security Management | 0.713 | 0.797 | |||

| 4. DC: Digital Capabilities | 0.570 | 0.602 | 0.549 | ||

| 5. RM: Risk Management | 0.817 | 0.668 | 0.705 | 0.458 | – |

| Relationship | Path Coefficient | t-Value | 95% CIs (Bias Corrected) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC → CM | 0.188 ** | 3.257 | [0.069, 0.285] | Supported |

| DC → RM | 0.070 | 1.133 | [−0.066, 0.187] | Not supported |

| DC → IDL | 0.545 *** | 10.470 | [0.442, 0.640] | Supported |

| DC → ISM | 0.466 *** | 8.096 | [0.349, 0.568] | Supported |

| IDL → CM | 0.324 *** | 3.656 | [0.165, 0.506] | Supported |

| IDL → RM | 0.334 ** | 3.343 | [0.150, 0.546] | Supported |

| ISM → CM | 0.273 ** | 3.008 | [0.096, 0.449] | Supported |

| ISM → RM | 0.332 ** | 3.380 | [0.132, 0.517] | Supported |

| Relationship | Path Coefficient | t-Value | 95% CIs (Bias Corrected) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC → IDL → CM | 0.177 ** | 3.383 | [0.088, 0.300] | Supported |

| DC → ISM → CM | 0.127 ** | 2.840 | [0.046, 0.225] | Supported |

| DC → IDL → RM | 0.182 ** | 3.191 | [0.082, 0.304] | Supported |

| DC → ISM → RM | 0.155 ** | 3.186 | [0.057, 0.258] | Supported |

| Stoner-Geisser Q2 | R2 | GOF | ||

| Change Management | 0.287 | 0.449 | 0.359 | |

| Information and Data Literacy | 0.199 | 0.297 | 0.243 | |

| Information Security Management | 0.175 | 0.217 | 0.195 | |

| Risk Management | 0.334 | 0.425 | 0.377 | |

| SRMR | 0.063 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Slavković, M.; Pavlović, K.; Mamula Nikolić, T.; Vučenović, T.; Bugarčić, M. Impact of Digital Capabilities on Digital Transformation: The Mediating Role of Digital Citizenship. Systems 2023, 11, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11040172

Slavković M, Pavlović K, Mamula Nikolić T, Vučenović T, Bugarčić M. Impact of Digital Capabilities on Digital Transformation: The Mediating Role of Digital Citizenship. Systems. 2023; 11(4):172. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11040172

Chicago/Turabian StyleSlavković, Marko, Katarina Pavlović, Tatjana Mamula Nikolić, Tamara Vučenović, and Marijana Bugarčić. 2023. "Impact of Digital Capabilities on Digital Transformation: The Mediating Role of Digital Citizenship" Systems 11, no. 4: 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11040172

APA StyleSlavković, M., Pavlović, K., Mamula Nikolić, T., Vučenović, T., & Bugarčić, M. (2023). Impact of Digital Capabilities on Digital Transformation: The Mediating Role of Digital Citizenship. Systems, 11(4), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11040172