Abstract

Urban flood risk communication continues to challenge governments. Community-based organizations (CBOs) aim to rapidly detect deficiencies in capacity to deal with flood risk in vulnerable communities and disseminate accessible risk information to assist in the selection and implementation of risk mitigation measures. This paper discusses the methods through which CBO members think their work is beneficial in the response to urban floods. Grounded theory is utilized to guide a mixed-method approach that included semistructured interviews with CBO members (N = 34), participatory observations, and policy document analysis. The findings show that localization of risk knowledge and the emergence of new social networks are important factors in flood risk communication in vulnerable communities. This discovery may highlight the varied aspects of creating community resilience and explain why traditional risk communication is currently unsuccessful. Our findings also shed light on the priorities associated with urban flood risk communication. Only by linking flood risk management to actual livelihoods can we ensure the smooth execution of relevant disaster mitigation measures, especially for vulnerable groups.

1. Introduction

Flooding has become a greater global hazard than any others due to rising global climate change. Worldwide flood losses have been increasing at a much faster pace than global GDP [1]. Flood perils impacted an average of 82.7 million people per year from 2001 to 2020, resulting in annual economic losses of USD 34.1 billion and 5185 deaths [2]. The year 2021 saw more negative effects from floods than the annual average of the preceding two decades because of a string of catastrophic flood events. There were more than 20 severe floods in Asia in 2021, once again the highest number of any region. In India, for instance, during the monsoon season, over 1400 people died due to various floods, and in July, the devastating Henan flood in China killed 352 individuals, while the Nuristan floods in Afghanistan killed 260 [2]. In response to the increasing number of floods, many authorities have dedicated greater pre-event investment to structural and nonstructural measures, and this has undoubtedly worked effectively in terms of decreasing fatalities and catastrophic economic losses [3]. The majority of Asia’s emerging nations now devote a significant percentage of their budgets to reducing flood risk along key rivers and in coastal areas. Even though flooding has also caused harm in inland communities, urban flood risk control strategies are frequently insufficient.

The complex environment with multiple and compound risks magnifies the inadequate urban flood risk management systems [4]. In the context of post-pandemic recovery, the top-down urban risk management process has revealed a lack of public engagement and flaws in collaboration and feedback procedures [5,6,7,8]. Accelerated urbanization has certain negative consequences. On the one hand, due to resource constraints, the renewal of risk-mitigation-oriented infrastructure and management initiatives is lagging drastically. On the other hand, vulnerable groups’ exposure, vulnerability, and capacity to cope with crises are significantly lower than the metropolitan average, and they are frequently excluded from urban development frameworks [9].

To build community resilience, this study focuses on the effects of flood risk communication by community-based organizations (CBOs) in vulnerable communities. The motivation for undertaking flood risk communication is diverse [10], but the relevant academic literature usually agrees on the following risk communication arguments: (1) risk communication can facilitate it for residents to participate in the management of flood risk [11,12]; (2) community cooperation is necessary for public sector flood risk mitigation measures, in which risk communication serves as a coordinating mechanism to establish emergency interactions [13,14]; (3) risk communication’s role in fostering trust is unclear, and a rigid approach to risk communication could backfire [12,15,16,17,18]; (4) the empirical findings demonstrate that risk communication, as opposed to coercive administrative orders, makes it easier to adopt community-based risk mitigation measures [19,20,21,22,23,24]. We agree that deepening the understanding of urban flood risk and responding to reduction measures by making more active use of existing technology and model frameworks is a chief task of flood risk communication [25]. This requires authorities to have a full picture of reality and the expected performance of resident participation in the systems, as well as a clear understanding of the actual demands of communities. As a result, another objective of risk communication is to establish adequate information exchange channels between risk experts and the broader community, especially vulnerable populations.

We performed the first field survey on flood risk governance and risk communication in vulnerable communities in China, in comparison to the previous literature. This paper contributes by emphasizing the importance of CBOs and improving the qualitative analysis of successful flood risk communication experiences; as a consequence, the selection of explanatory samples emphasizes sample information richness and analytical capability rather than sample representativeness, and we attempt to answer the following questions: How can CBOs successfully increase the efficiency of risk communication, and why can CBOs be competent? What is the nature of flood risk communication in vulnerable neighborhoods, and what are the implications of the role of CBOs in urban flood risk governance?

The study contributes to the literature on urban flood mitigation and, specifically, to public participation and management system enhancement. Vulnerable communities are exceedingly heterogeneous [9,15,17,18,20,26,27,28], and this study used qualitative approaches to explore the unique position of CBOs in the systematic strategy. The urban flood risk management system in Shijiazhuang, China, should be viewed as a model for growing Asian countries. First, the practices of local CBOs in flood risk communication were researched to identify what factors are crucial to communication. Second, this study explores the state of CBOs’ flood risk communication to understand and identify the obstacles involved and to provide ideas for advancement.

The next section presents a review of community resilience and risk communication. Section 3 describes the flood risk communication in Shijiazhuang as a case study, as well as our qualitative research methods. The findings and discussion are presented in Section 4 and Section 5, and our conclusions are offered in Section 6.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Resilience in Vulnerable Communities

The concepts of vulnerable community resilience are relevant to discuss as conceptual pillars of this research. Typically, resilience and vulnerability are seen as two sides of the same coin. Communities are becoming or have become vulnerable to a variety of elements that influence the extent to which an event or series of events in nature and society diminish a group’s life, livelihood, property, and other assets [29]. Unlike the many constraints implied by vulnerability [30], resilience highlights an individual’s or group’s ability to resist the damaging consequences of a hazard and recover quickly, and the capability is formed from multiple dimensions simultaneously or sequentially. Thus, most research excludes the social processes of some attempts to end vulnerability once and for all (e.g., [31,32,33]), which is a much larger social or economic issue. More studies focus on the current state and changes in sensitivity to emergency preparedness and crisis resistance in situations where vulnerable communities’ limitations cannot be lifted in a timely way [25,32,34,35,36].

Beck’s research is particularly illuminating considering the broad and developing literature on vulnerability [37]. His work and the debate it inspired about the “risk society” are still important in the contemporary setting of growing urbanization. At the same time, a vital objective of urban risk management strategies is to educate vulnerable communities about the benefits of effective risk adaptation measures and to provide financial support accordingly, rather than to make vulnerable populations aware of disaster risks or to instill fear of crisis.

There are significant obstacles to operationalizing effective flood management solutions in cities of developing countries, including expanding informal settlements, inefficient resource allocation, corruption, insufficient infrastructure, and the sheer magnitude of the problem of reacting to COVID-19 [38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Finally, adequate access to an urban risk management network is a key to vulnerable communities’ resilience, which can be characterized as follows: (1) capacity to coordinate and mobilize to maximize the public’s attention and participation in pre-disaster-response decisions and actions and to reduce the adverse consequences of disaster events; and (2) the development and application of transferable knowledge, methods, and instruments that drive community changes in keeping with the objectives of a city’s flood risk management system.

2.2. Flood Risk Communication

Risk communication aims to empower those who are exposed to various sorts of hazards to make sensible decisions that will lessen the impact of threats and hazards, as well as increase preventative and protective measures [45,46]. The traditional top-down approach to risk communication has come under fire for failing to keep up with the development of information technology and failing to adequately explain the rising complexity of hazards [47,48,49,50]. Some developing research looks at the connection between risk communication and community engagement [20,44].

It is obvious that the ability of significant rainfall events to create urban floods everywhere clashes with previous experience and local understanding. The urban flood risk communication is critical in attempts to strengthen the interaction between risk expertise and localized practice [14]. This has a direct influence on risk information application and is represented in what and how communication occurs, as well as through what channels, by whom, and for whom [25,51,52,53,54].

The terms “flood risk communication” and “flood emergency messaging” have completely different meanings and correspond to the catastrophe preparedness phase and the emergency response and recovery phase, respectively. The success of the former in creating a network of trust for risk management is correlated with the effectiveness of the total flood risk response strategy in the later phases [55]. A significant impediment is that during the preparedness phase, public concerns and participation in risk mitigation initiatives may not correspond with the objectives stated by risk management specialists. It is debatable whether the general public fully comprehends the consequences of specialists’ descriptions of the likelihood and severity of urban floods. On the other hand, Wisner argues that rigid disaster preparedness methods frequently miss the basic problem of disaster vulnerability, namely, neglecting the basic risk information and disaster mitigation demands of most economically and politically vulnerable communities [29].

Community cultural characteristics that impede flood risk communication are frequently disregarded when analyzing flood risk communication strategies in emerging economies [56]. In view of all that has been mentioned, one may suppose that implementing flood risk communication in developing nations—which focuses on incorporating localized knowledge and community cultural values into flood risk analysis—will have a positive influence.

3. Materials and Methods

This paper used a mixed-method approach that included semistructured interviews with members of CBOs, policy document analysis, and participatory observations. The three ways for collecting data allowed for triangulation, which confirmed, corroborated, and improved the reliability and validity of the data. The study was conducted according to the ethical standards for interviewing humans as followed by Nankai University’s academic staff. The participants were informed about the ethical procedures when asked to participate and that their personal details would not be disclosed.

3.1. Grounded Theory Analysis

Grounded theory is a method for developing abstract theories based on concrete data using a heuristic procedure. Rather than validating a preexisting idea, grounded theory seeks to generate theory by systematically collecting and analyzing data. Despite being a qualitative method, it combines the rigorous and logical systematic analysis of quantitative research with the insightful and complex explanations of qualitative research. The grounded theory’s main process is a three-stage analysis with three levels of coding: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding [57]. Throughout the process, theoretical saturation tests are run to augment the information until the theoretical model is complete.

In risk management studies involving emerging economies, urban flood risk is mostly ignored, and there is a dearth of mature theory to serve as a guide for community governance and community resilience development in the developing world in the setting of elevated urban flood risk. A lack of situational validation from actual cases and real-life stories characterizes current research on community resilience in China, which is primarily based on secondary data and empirical analysis of some traditional variable relationships in the fields of sociology and management. This is especially true given that the majority of theoretical concepts related to community resilience in urban development contexts and local scenarios have not yet been established and refined. Furthermore, there is a massive amount of qualitative data available for research, such as localized stories and practices in CBOs’ risk communication. In light of this, this paper employs grounded theory as a research methodology to clarify the role of CBOs in flood risk management in vulnerable communities.

3.2. The Study Area

Shijiazhuang is located in North China and the Bohai Bay Economic Zone, approximately 283 km southwest of Beijing, China’s capital. Shijiazhuang has a temperate monsoon climate with a total annual precipitation of 401.1–752.0 mm, including 628.4–752.0 mm in the western mountainous areas; precipitation from June to September accounts for 63–70% of the annual precipitation, influenced by warm and humid ocean currents.

Inland flooding within the city of Shijiazhuang, where it frequently occurs after excessive rainfall, poses a major threat to vulnerable residents [58,59]. The purpose of the policy document analysis is to comprehend the state of urban flood management in Shijiazhuang as well as the traits of vulnerable communities, which is necessary to enable us to identify four representative vulnerable communities. Table 1 displays the basic socioeconomic features for the sample communities, with names and precise locations obscured. Then, we spent five days in the field, experiencing daily community activities and special events in the vulnerable communities—which were during a July rainy season—and observing their varied flood risk communication services. The first conceptualizations and patterns were greatly influenced by these observations, allowing us to investigate the social milieu from within.

Table 1.

Communities’ characteristics.

3.3. Recruitment and Participants

Participants for this study were gathered using snowball sampling in three stages, each of which served as a guide for the subsequent phases of data collection and were guided by grounded theory. Between July and November 2021, 34 members of CBOs who took part in flood risk communication in communities at risk were recruited in Shijiazhuang City, Hebei Province, China. Each participant underwent a semistructured interview in a casual setting to ensure that they could express themselves completely and accurately. Participants ranged in age from 27 to 54 at the time of the interviews and had been involved in community management or other related work for anywhere between 11 months and 18 years (see Table 2). Full-time employees and volunteers are identified and marked with the cards “ZZ” and “ZY” throughout the anonymization procedure. All participants reported being aware of flood risk communication and performing practical activities, which lowered the possibility that they would misunderstand questions owing to cognitive barriers and practical ignorance. From July to August 2022, 79% of the respondents received a return visit in the form of a telephone interview.

Table 2.

Participants’ characteristics.

Appendix A contains a guide used for the semistructured interviews. The themes discussed in the interviews included prior experiences with flood risk communication, significant factors affecting flood risk management, drivers, and barriers to implementing flood risk communication in vulnerable communities, interactions with governmental actors and neighborhoods (i.e., process, type of communication), reflections on the risk communication process, and the role of CBOs in the process. A total of 63 h of interviews were audio-recorded with participant agreement.

We used a qualitative content analysis to categorize and distill relevant information from coded interview transcripts and documents within the software package NVivo. Following the completion of all interviews and analyses, an additional seven qualified community residents and three flood risk management experts at the regional level were recruited for a membership check, all of whom agreed with the previous analysis results.

4. Findings

4.1. Open Coding

Open coding is the process of categorizing words and phrases in survey materials and assigning subjective interpretations to them. We used NVivo to develop and manage open codes by assigning text segments to different nodes. As the open coding developed, we also spent substantial time revisiting the concepts by renaming, combining, or eliminating some codes. Finally, the theoretical saturation point, where no new codes are generated, was reached. Table 3 shows the 48 open codes that were created from the data. Table 3 also shows how many data sources each code appears in.

Table 3.

List of codes that emerged from the open code analysis.

4.2. Axial Coding

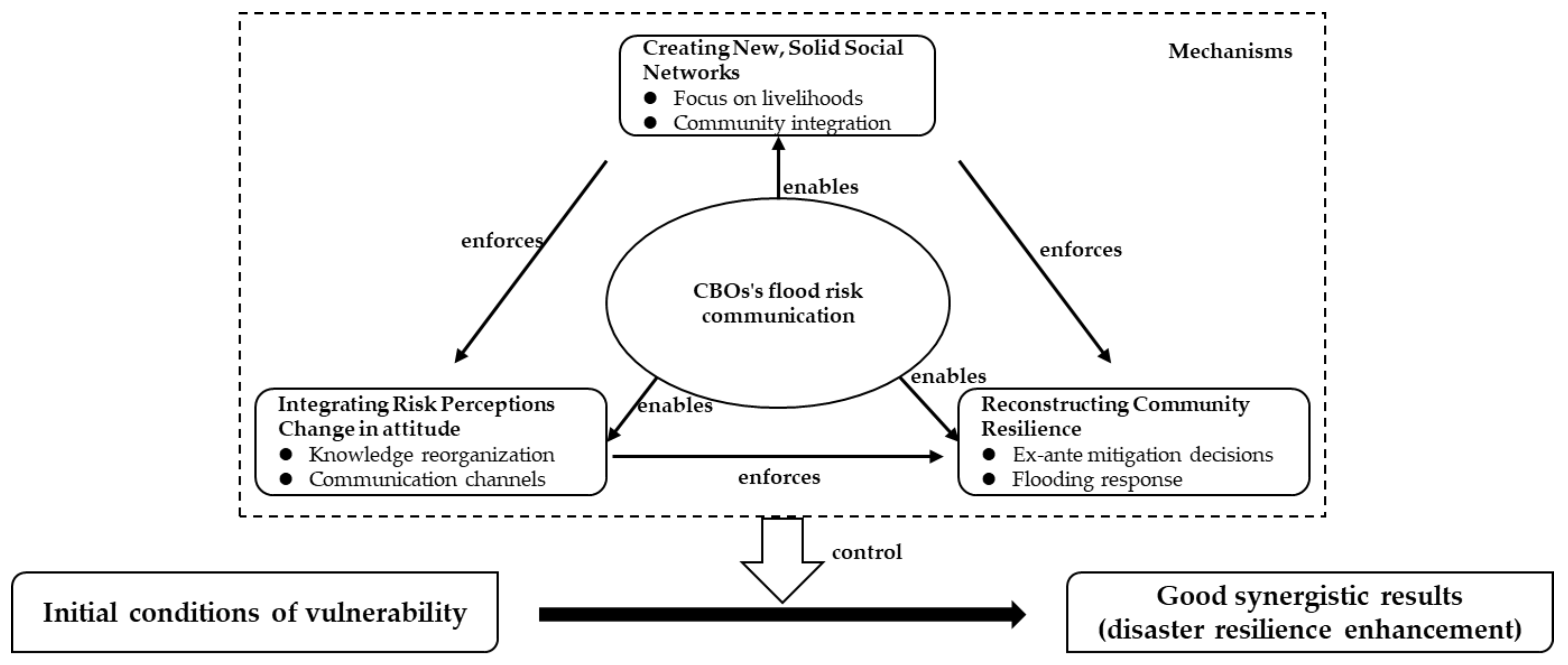

Axial coding is the process of making logical, connotational, and emotional links found in open coding, that is, connecting categories and interpreting their logic. Axial coding establishes the research’s focal point, enhancing the theory’s capacity to explain topics and social contexts while also creating a correlation channel between practice and theory. Three core categories—including creating new, solid social networks, integrating risk perceptions, and reconstructing community resilience—were ultimately developed through this axial coding method. These three core categories, which are described in Table 4, define the main dimensions of the study topic.

Table 4.

Relationship between 3 core categories, categories, and open codes.

In Shijiazhuang, CBOs were successful in influencing vulnerable community members to take advantageous actions to reduce their exposure to flooding during the flood risk communication process. The three contextualization mechanisms for achievement shown by the core categories are as follows:

4.2.1. Creating New, Solid Social Networks: A Livelihood-Based Gesellschaft

In From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society1, famous Chinese sociologist Fei Xiaotong described the contrasting organizational principles of Chinese and Western societies. Fei’s theoretical claims regarding the characteristics of Chinese society are still valid today, but social networks in major cities have undergone significant transformation. A prominent illustration of this is vulnerable communities in cities, which are a type of informal settlement without the ritual order based on blood and location and with decaying, outmoded architectural styles that clash with the bustling infrastructure of the metropolises that surround them. CBOs’ preliminary objective is to help these at-risk populations develop internal social ties. The idea behind this is that residents can decide how to minimize flood risk based on shared interests.

Whether they are full-time employees or volunteers with diverse career backgrounds, CBOs’ members may have numerous identities but work to integrate into vulnerable areas. As identities shift, CBOs that participate in “linkage” activities might also succeed in achieving a two-way engagement in local governance, i.e., engaging with grassroots government actors while providing disadvantaged people a full voice. Since CBOs serve as a platform for connecting groups within vulnerable communities, the gradual emergence of a new social network that includes them will make risk communication easier. ZY17 concluded that CBOs’ role positioning was the key to their effective flood risk communication and that CBOs’ members’ excellent service attitudes—which included daily life service and mutual aid service in addition to risk communication—helped to create a positive interactive relationship with the community.

“We were never labeled ‘experts’, even when we had to use formal language to define risk in the context of complex problems. In China, renowned experts such as Professor Zhong Nanshan, whose perspective on infectious diseases inspires both the proper response and high levels of public confidence, have a significant influence. At least for the time being, the ‘expert effect’ does not apply to the subject of flood risk management. CBOs are not seen as commanders but rather as regular citizens of the community, and this decreased emotional distance makes it easier for people to absorb communications about flood risk”.(quotation from ZY17)

“When we employ urban flood risk communication, the most essential thing is to obtain an interface to interact with vulnerable populations”.(quotation from ZZ2)

Not the sharing of flood risk knowledge, but, rather, concern for the livelihoods of those in need is where new social connections are first established. CBOs gained people’s acceptance by offering practical and emotional support to community members, and this favorable word-of-mouth swiftly spread throughout the neighborhood. Since some programs themselves imply an unequal relationship between provider and recipient, are viewed as a form of command or handout to the poor, and fail to address the underlying problems that people face, locals frequently find pro-bono-oriented community services repugnant. Instead, being a part of a vulnerable community, communicating flood risk accurately, and providing advice on emergency preparedness and mitigation based on the needs of the vulnerable help to decrease this feeling of alienation.

The new social network has a significant impact on risk communication topics as well as the overall enlightenment of the participants in the social–ecological system of managing flood risk in communities at risk [60], including, but not limited to, the innovation of the method of communication with local government agents, meteorological departments, and emergency management departments. It can be described as a two-way formation of social networks using both endogenous and exogenous sources, which is stated to align with an effective framework for risk communication. One volunteer leader praised the pro-people approach taken by CBOs, stating that

“Our efforts include going from home to house to understand and attempt to help people with their livelihood difficulties, as well as carrying out group activities that not only take residents’ needs into account but also improve the inclusive environment. Residents’ quality of life has improved after taking essential precautions with our guidance, which has benefited our future offline and online risk communication tactics. Residents truly think that our efforts or recommendations are meant to improve their welfare. On a voluntary basis, many residents also take part in our efforts to enlighten other community members about flood risk awareness and risk reduction”.(quotation from ZY1)

Resulting from the abovementioned creation of the new social network, many previously prosocial behaviors become theoretically self-interested for the individual. CBOs have helped most people living in vulnerable and marginalized communities identify raising their standard of living as a common action goal. In this context, collective community decisions on flood risk management are no longer taken under social or altruistic pressure but, rather, serve to advance the fundamental interests of vulnerable community members and advance the growth and improvement of both people and communities. It demonstrates how, exactly in line with the findings summarized by our participatory observations, the new social network in Shijiazhuang’s at-risk neighborhoods does not enable the communities to function as a typical Chinese rural geosocial model but, rather, transforms emotions and identity into shared objectives and performs a Gesellschaft in which individual actions are improved on a continuous basis and group decisions are successfully pushed and carried out.

4.2.2. Integrating Risk Perceptions: Bridging Knowledge and Local Experiences

Since the concept of resilience was incorporated into China’s framework for managing flood risk, the issue of localizing flood risk knowledge has become a key concern [61]. These CBOs promote the idea that addressing community needs and acting in a way that is best in line with local culture and values should come first when finding solutions to problems. Therefore, CBOs distinguish between the localization of flood risk knowledge, i.e., the localization based on perceived flood risk characteristics, and the localization based on the formulation of action plans within the limitations of vulnerable circumstances under the objective condition that the risk information requirements of vulnerable populations reflect the characteristics of generalization.

“Knowledge localization based on perceived flood risk characteristics” has significant limitations. (1) Perception is constrained by distinct environmental and temporal constraints, and its uniqueness is difficult to recreate across groups. Because of this defect, flood risk communication cannot be repeated on a broader scale, which explains the failure of the local meteorological departments’ attempts to raise public awareness of flood dangers by short video platforms. (2) Localization of knowledge based on perceived flood risk characteristics tends to stay on the more superficial level of experience communication, such as imitation and replication, and is incapable of rising to the level of universal scientific meaning to comprehend [62,63]. This means that systematically capturing core knowledge from experience or events might be difficult, and the biased application of subjective risk perceptions can limit the effectiveness of risk communication. When CBOs began to serve the underprivileged as local organizations, the prevalence of these limitations was a serious hurdle.

CBOs have increased their coordination with agencies in charge of managing flood hazards to provide vulnerable communities with a framework that is agreeable and recognizable for the concept of risk. As ZZ7 points out,

“We have conferred with meteorological experts quite a bit. The cliché problem of how to explain to the general public why ‘once-in-a-century’ floods have occurred so frequently recently is one example of this. We attempted to match a large number of examples in order to highlight the traits of common situations, the evolution of different disaster outcomes, the paradoxical nature of urban flood probability, and the benefits of disaster preparedness.”

Then, short-term implementable preparedness strategies and technical and financial help CBOs may give, as well as long-term flood risk sensitivity inculcation, are among the themes of risk reduction. The CBOs’ visits strengthened the previously created interaction with residents after clarifying the topic of risk communication. In addition, thanks to the preconstruction of risk response mechanisms, the effectiveness of emergency response approaches (including emergency evacuation, self-help, and mutual assistance) in the case of a real catastrophe was validated for the 2021 rainy season2.

The cornerstone of “knowledge localization based on action formulation” is understanding how vulnerable groups perceive and react to hazards locally. Following the identification of knowledge components that are professionally relevant to risk management advancement, CBOs and risk experts conceptualize these local experiences through theoretical elaboration and analysis, which is reflected in the scientific transformation of informal risk perspectives into professional concepts or terminology that can be shared and utilized by relevant professional practices. After obtaining and analyzing several risk knowledge items, CBOs eventually incorporate local experience into the risk management knowledge system.

CBOs’ “risk communication” is involved in all four phases of flood risk management to varying degrees: early warning and surveillance; prevention and preparedness; response operations and rescue; and rehabilitation and recovery. In each phase, the experts and CBOs conducted an adaptive exploration of community risk management elements with the goal of bridging expertise and generalized experience to reprocess practically meaningful risk mitigation guidance strategies. The existence of potential risks and the benefits of coping strategies are frequently mentioned in communities, expanding from verbal communication to dissemination on online platforms, where residents of vulnerable communities have the interface to consider risks and individual livelihoods together. Although risk perception is a long-term, complex process influenced by a variety of factors, including culture and education, risk communication strategies pioneered by CBOs that are oriented toward the outcomes of mitigation actions and emergency response options can assist residents in making science-based decisions.

“When all outcomes point to improved livelihoods, the risk knowledge framework developed by CBOs gains traction for widespread transfer”.(quotation from ZY4)

4.2.3. Socially Reconstructing Community Resilience

As determined most clearly by a measurement of the community’s environment and organizational management capabilities, resilience denotes the coordination and unity of a community’s physical space and social systems [64]. CBOs invest initially in disaster preparedness support for the physical environment in vulnerable communities, offering the most basic material and equipment support for the growth of resilience. The next step is for CBOs to standardize and organize managerial and organizational soft power in terms of fostering community resilience. It has been successfully implemented to provide transparent, effective, and multiparticipatory public services and management systems that incorporate the decision-making procedures that foster community resilience.

The original vulnerable community management paradigm limited the ability for multiactor engagement in governance. As previously stated, CBOs revitalize a community’s social network, and their most significant effect is the building of trust and reciprocity in the community. Once trust and public participation are established, the community’s collective decision-making and implementation process becomes more reliable, for example, by strengthening the implementation of ex ante mitigation measures such as infrastructure upgrades and disaster insurance agreements and by ensuring that residents respond appropriately to emergency flood evacuations, among other things. ZY8 claims that

“In vulnerable areas, the issue of harmonizing public interests is typically a problem for risk governance. Many of the flaws can be solved by increasing the number of decision-makers and improving feedback methods. The primary goal of flood risk management is to protect people’s livelihoods. Finally, our efforts resulted in a gradual change in the community’s single, inflexible management paradigm.”

The resilience of vulnerable populations is significantly harmed by pandemic shocks because there is a lack of economic diversity and stability. The possibility of inhabitants suffering health harm or income interruptions as a result of the pandemic is juxtaposed with the property and life dangers of urban floods. The information in CBOs’ risk communication needs to be diversified because of the overlap of hazards. Numerous projects to increase the resilience of infrastructure and organizational systems have seen quick updates. An unanticipated conclusion was that, in addition to improving the transmission of risk knowledge and the implementation of mitigation measures, CBOs’ risk communication considerably reduced the negative emotions that had collected in the minds of residents as a result of the ineffectiveness of the epidemic response.

4.3. Theory Building

This study first demonstrates the theoretical connection between the CBOs’ risk communication and social networks. The findings imply that the relationships among vulnerable community members and their interactions with outside stakeholders affect the effectiveness of risk communication during the response to an urban flood disaster. Strong mediation links between various vulnerability groups, as represented by CBOs, are especially important for improving disaster prevention instincts, risk perceptions, and risk communication practices. The capacity to send and receive information across various cohesive networks is substantially correlated with the effectiveness of urban flood risk communication between CBOs and vulnerability groups. A relationship that “enables” can be suggested between the CBOs’ risk communication and social network remodeling.

Second, the findings of this study point to a connection between CBOs’ risk communication and risk perceptions. Effective risk communication depends on the effective integration of professional risk knowledge and local risk experience. Participatory observations also identify the strong correlation between risk communication and risk perceptions. The findings also show that when locals have unfavorable opinions about conventional risk communication, the effectiveness of shared decision-making for disaster prevention and mitigation may suffer. For instance, community members reduced their intentions to self-mitigating flood risk and rejected subsequent risk communication when they began to believe it was more advantageous to be assisted by the government after a disaster. Thus, when negative beliefs emerge among vulnerable groups, risk communication leads to fewer resilience-enhancing outcomes, and vice versa.

The findings of this study imply that social networks and risk perceptions are related. When CBOs actively engage in risk communication and there are numerous strong links between members of vulnerable groups, residents have more opportunities to learn about urban flood risk and indirectly spread or reinforce risk perceptions among other residents. Therefore, a group’s interconnected links enable risk communicators to rapidly share fresh flood risk information. Additionally, inhabitants of a community with strong intimate ties are more likely to contact CBOs by feeding back their demands for risk reduction.

The study’s fourth relationship discovery is the link between community resilience and CBOs’ risk communication. CBOs’ activities influenced flood risk reduction and emergency preparedness in high-risk neighborhoods. These vulnerable groups could, for instance, adopt the principle of maximizing the welfare of the community and take actions that strengthen community resilience. CBOs exchange bits and pieces of evidence of mutual assistance resulting from hazard mitigation driven by livelihood development.

Fifth, how people perceive flood risk has a direct impact on how resilient a community is. For instance, this study further isolates views of urban flood danger as a shared cognitive model created by an interest group that is motivated by their goal to improve their standard of living. It is beneficial to reinforce or correct risk perceptions. Residents contributed to mitigation despite the difficulties when they realized the hazards of flood risk. Residents of vulnerable communities are more willing to develop resilience when they perceive risk.

Finally, the restructuring of social networks can be seen, on one level, as a particular path to improving community resilience.

The above findings imply that vulnerable communities’ proper understanding of the formal system of meaning of urban flood risk prevention and response is due to the molding of social networks and risk perceptions brought about by risk communication by CBOs. CBOs’ risk communication enhances disaster response among vulnerable populations. Residents’ comprehension of the urban disaster management system and their ability to make wise decisions on catastrophe mitigation depend on the effectiveness of each level of risk communication.

An integrative diagram showing the relationships between the main categories that came out of this study is shown in Figure 1. CBOs’ involvement can lead to greater synergy levels. The findings also show that social network optimization can improve the beliefs and confidence of vulnerable groups to build more resilient communities. Communities can establish a shared view of risk when there is a willingness to mitigate that is livelihood-centered. One illustration is how the livelihoods of those who are struggling have been significantly impacted by COVID-19, and, through their prior influence, community organizations aided local governments and citizens to create and sustain a consensus on epidemic control to a certain extent.

Figure 1.

Theory of CBOs’ risk communication in vulnerable communities: integrative diagram reflecting the relationships among the core categories *. Note: * The dashed box is considered to be the general mechanism for CBOs to engage in vulnerable communities’ risk communication, which directly affects the procedure of local disaster preparedness and response.

5. Discussion

The available research emphasizes the need for public involvement in urban flood risk management and suggests that the first step is to provide the public with a scientific understanding of the potential threats [12,16,65,66]. As a result, various theoretical frameworks for including the community in flood management have been proposed. The majority of studies, however, have ignored vulnerable people by neglecting the state of their livelihoods and the relationship between such livelihoods and the steps they take to reduce flood risk [67]. We also point out that vulnerable groups in earlier research have typically been based on the least developed nations, which is obviously crucial and essential [3,18,36]. However, in typical developing nations, we place more emphasis on the growth of metropolitan areas with economic promise, many of which contain vulnerable communities. These marginalized neighborhoods are more frequently ignored and subject to greater intraurban disparities. The process used in Shijiazhuang, China, as a case study may provide insight into how to improve flood risk communication. It is critical to concentrate on vulnerable people in cities, where survival has become increasingly tough as a result of the twin shocks of climate change and pandemics. Our findings are in line with several exploratory studies that examine effective strategies for enhancing resilience in high-risk locations, such as the effects of lowering floods, earthquakes, and manmade disasters, as well as the benefits of assisting marginalized residents [5,46,68,69]. Although the anticipated effects of CBOs involved in risk communication support the critical importance of frameworks to manage flood risk [41], the specific content still has to be adjusted in accordance with the social and cultural context [70].

This study demonstrates that these CBOs are seen as playing prominent roles in the promotion of new social networks and the localization of risk knowledge, which influences risk perceptions as well as the capacity and attitudes of vulnerable communities to participate in governance. To promote residents’ comprehension of community resilience performance levels based on objective assessment and prevent the deviation of disaster preparedness and emergency self-rescue decisions, community resilience is strongly linked to individual livelihoods. As a go-between for residents and risk experts, CBOs not only enable contextual transformation of risk knowledge based on the trust mechanism but also realize the refining and feedback of residents’ risk information needs. The enrichment of risk management participants optimizes the flood risk management operation mode, which comprises stripping and reengineering the original government participants’ activities [71]. Given the changing risk environment, the most pressing question is whether sensible choices for sustainable urban flood risk management are available, particularly for moving away from top-down approaches when prioritizing the resilience of vulnerable areas. The slow implementation of risk mitigation measures in many developing nations is a result of bloated government operations, but CBOs can step in to replace government agencies and finish the task of influencing the public’s perception of risk.

The study’s significant contribution is that it is a response to strengthening resilience in vulnerable populations. To address the absence of public disaster response capabilities, the early notion of public involvement centered on whole-of-society engagement in emergency management problems [69,72,73]. This paper expands this theory from emergency management to ex ante risk response, summarizing the essential concepts and mechanisms of flood risk communication in this setting. The findings support the basic theoretical principles that CBOs play a role in disaster mitigation acts such as trust, reciprocity, knowledge transmission, and decision-making.

Therefore, our findings support the critical role played by CBOs’ risk communication in fostering effective resilience-related sense-making. To ensure information is exchanged and organized during an incident, effective coordination across all parties involved is essential.

6. Conclusions

This study focused on CBOs to determine how they may manage flood risk communication to develop resilience in vulnerable communities. The current situation is thoroughly investigated by employing a variety of methodologies, in which traditional risk communication has difficulty being effective in vulnerable groups, and, thus, risk knowledge is lacking under many contextual systems. Although the sharing of risk information and collaborative disaster adaptation options generates the idea that communities band together to deal with disasters, this is not the only step that successful CBOs take. Community trust, reciprocal relationships, and shared goals of improving livelihoods developed through knowledge acquisition and trust mechanisms are the driving forces behind the gradual improvement of community resilience, even though not all people are willing to accept disaster reduction strategies in a short period of time. It is crucial for policy and practice to comprehend how CBOs approach the problem of risk communication and how to unite diverse stakeholder demands into a community of interests centered on catastrophe prevention and mitigation. The approaches that have been found pertain to enhancing flood risk management and mobilizing the populace for group activity in the interest of boosting social resilience.

This study adds to the research on improving community resilience from the perspective of a “social–ecological system,” which expands the participants and alters the development mode of the actors’ interaction accordingly. Regardless of the number of vulnerable communities, more broad and universal governing experiences are always needed. In this study, the risk communication systems drawn from the case-building theory may have limitations. Future research might investigate whether CBOs are the optimal choice of agents for flood risk communication, as well as the pleiotropy of community risk communication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L.; methodology, Q.L.; software, Q.L.; validation, Y.L.; formal analysis, Q.L.; investigation, Q.L. and Y.L.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social Science Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China (21YJA790041); and the Major Research Project of China Earthquake Administration (CEAZY2022JZ02).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the advice provided by researcher Hesheng Chen. We would like to thank everyone who was involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Guide to Semistructured Interviews

Duration: On average 35 min.

Type of Interview: Semistructured.

Process:

- Step 1:

- Discuss potential flood risk management or risk communication scenarios with participants and plan a review of the scenario with them. On any specific aspect, participants may be asked to provide more details.

- Step 2:

- Describe to the respondents the goal of the interview. The scientific category of “flood risk communication” given in the scenario is meant to illustrate how community governance is driven by participants’ work.

- Step 3:

- The participant is then asked to elaborate on the work-in-progress and make a list of its key components.

With that, the main query was raised: How can you, under the aforementioned scenarios, engage in flood risk communication in vulnerable areas to assist in the creation of useful judgments on flood risk mitigation?

Here are some examples of possible inquiries:

- (1)

- How can residents better grasp flood risk information?

- (2)

- How will you respond if locals are uncertain about risk communication?

- (3)

- How should you prepare to carry out your risk communication tasks?

- (4)

- What method is used to improve communication between local populations and government agencies?

- (5)

- How resilient is the community to disasters now, in your opinion?

- (6)

- Has the effectiveness of early risk communication been demonstrated in the context of emergency flood risk avoidance information?

- (7)

- What are the key obstacles to the development of community-wide flood risk mitigation?

Notes

| 1 | From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society, the representative work of sociologist and anthropologist Fei Xiaotong, is a compilation of his lecture notes from the late 1940s, when he taught rural sociology at the National Southwest Associated University and Yunnan University. The English version was published by the University of California Press in 1992, and can be viewed at http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pn6km. (accessed on 18 November 2022) |

| 2 | The catastrophic effects of massive floods brought on by heavy rain in Henan Province in 2021 shook China. In fact, the subtropical anticyclone over the western Pacific caused severe rainfall in Shijiazhuang in July 2021. However, Shijiazhuang’s casualties and property damages were kept to a minimum thanks to efficient disposal. |

References

- Bevere, L.; Remondi, D.F. Natural Catastrophes in 2021: The Floodgates Are Open; Swiss Re: Zurich, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/sigma-research/sigma-2022-01.html (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- CRED. 2021 Disasters in Numbers; Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://cred.be/sites/default/files/2021_EMDAT_report (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Carrasco, S.; Dangol, N. Citizen-government negotiation: Cases of in riverside informal settlements at flood risk. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 38, 101195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahari, R.K.; Ariffin, R.N.R. Risk Communications: Flood-Prone Communities of Kuala Lumpur. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2013, 17, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corriero, A.C.; Khan, F.M.A.; Bassey, E.E.; Bouaddi, O.; Costa, A.C.D.; Outani, O.; Hasan, M.M.; Ahmad, S.; Essar, M.Y. Floods, landslides and COVID-19 in the Uttarakhand State, India: Impact of Ongoing Crises on Public Health. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021, 373, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aura, C.M.; Nyamweya, C.S.; Odoli, C.O.; Owiti, H.; Njiru, J.M.; Otuo, P.W.; Waithaka, E.; Malala, J. Consequences of calamities and their management: The case of COVID-19 pandemic and flooding on inland capture fisheries in Kenya. J. Great Lakes Res. 2020, 46, 1767–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonovic, S.P.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Wright, N. Floods and the COVID-19 pandemic-A new double hazard problem. WIREs Water 2021, 8, e1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, T.; Das, S.; Abe, M.; Shaw, R. Managing Compound Hazards: Impact of COVID-19 and Cases of Adaptive Governance during the 2020 Kumamoto Flood in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Stevens, S.P.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Wyche, K.F.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, Set of Capacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellens, W.; Terpstra, T.; De Maeyer, P. Perception and Communication of Flood Risks: A Systematic Review of Empirical Research. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grothmann, T.; Reusswig, F. People at risk of flooding: Why some residents take precautionary action while others do not. Nat. Hazards 2006, 38, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, C.; Moser, S.C.; Kasperson, R.E.; Dabelko, G.D. Linking vulnerability, adaptation, and resilience science to practice: Pathways, players, and partnerships. Glob. Environ. Change 2007, 17, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frewer, L. The public and effective risk communication. Toxicol. Lett. 2004, 149, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punt, E.; Monstadt, J.; Frank, S.; Witte, P. Beyond the dikes: An institutional perspective on governing flood resilience at the Port of Rotterdam. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanga, R.A. The role of local community leaders in flood disaster risk management strategy making in Accra. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 43, 101358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, D.; Irons, M. Communication, sense of community, and disaster recovery: A Facebook case study. Front. Commun. 2016, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poku-Boansi, M.; Amoako, C.; Owusu-Ansah, J.K.; Cobbinah, P.B. What the state does but fails: Exploring smart options for urban flood risk management in informal Accra, Ghana. City Environ. Interact. 2020, 5, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufat, S.; Fekete, A.; Armaş, I.; Hartmann, T.; Kuhlicke, C.; Prior, T.; Thaler, T.; Wisner, B. Swimming alone? Why linking flood risk perception and behavior requires more than “it’s the individual, stupid”. WIREs Water 2020, 7, e1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Cheng, X.; Huang, Q.; Chen, R.; Ward, P.J.; Aerts, J.C.J.H. Brief communication: Rethinking the 1998 China floods to prepare for a nonstationary future. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 19, 715–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, N. Collaborative emergency management: Better community organising, better public preparedness and response. Disasters 2008, 32, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, L.; Holmes, A.; Quinn, N.; Cobbing, P. ‘Learning for resilience’: Developing community capital through flood action groups in urban flood risk settings with lower social capital. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 27, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snel, K.A.W.; Priest, S.J.; Hartmann, T.; Witte, P.A.; Geertman, S.C.M. ‘Do the resilient things.’ Residents’ perspectives on responsibilities for flood risk adaptation in England. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2021, 14, e12727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Klemm, C.; Hutchins, B.; Kaufman, S. Emergency risk communication and sensemaking during smoke events: A survey of practitioners. Risk Anal. 2022, 13903, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.-L.; Cheng, W.-C.; Shen, S.-L.; Lin, M.-Y.; Arulrajah, A. Variation of hydro-environment during past four decades with underground sponge city planning to control flash floods in Wuhan, China: An overview. Undergr. Space 2020, 5, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, P.; Thaler, T. Flood-resilient communities: How we can encourage adaptive behaviour through smart tools in public–private interaction. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Boruff, B.J.; Shirley, W.L. Social Vulnerability to Environmental Hazards. Soc. Sci. Q. 2003, 84, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, T.G.; Scheid, C. Evaluation and communication of pluvial flood risks in urban areas. WIREs Water 2020, 7, e1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Ntim-Amo, G.; Xu, D.; Gamboc, V.K.; Ran, R.; Hu, J.; Tang, H. Flood disaster risk perception and evacuation willingness of urban households: The case of Accra, Ghana. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 78, 103126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisner, B.; Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Dessai, S.; Goulden, M.; Hulme, M.; Lorenzoni, I.; Nelson, D.R.; Naess, L.O.; Wolf, J.; Wreford, A. Are there social limits to adaptation to climate change? Clim. Change 2009, 93, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.B.; Woodrow, P.J. Rising from the Ashes: Development Strategies in Times of Disaster; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelling, M. The Vulnerability of Cities: Natural Disasters and Social Resilience; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S. Vulnerability and risk: Comparing assessment approaches. Nat. Hazards 2012, 61, 1099–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskrey, A. Disaster Mitigation: A Community Based Approach; Oxfam GB: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Azad, M.A.K.; Uddin, M.S.; Zaman, S.; Ashraf, M.A. Community-based Disaster Management and Its Salient Features: A Policy Approach to People-centred Risk Reduction in Bangladesh. Asia Pac. J. Rural Dev. 2019, 29, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, P.; Mitra, A.; Eslamian, S. Disaster management strategies and relation of good governance for the coastal Bangladesh. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2021, 3, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, U.; Lash, S.; Wynne, B. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity; SAGE: London, UK, 1992; Volume 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinh Hung, H.; Shaw, R.; Kobayashi, M. Flood risk management for the RUA of Hanoi. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2007, 16, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songsore, J. The Complex Interplay between Everyday Risks and Disaster Risks: The Case of the 2014 Cholera Pandemic and 2015 Flood Disaster in Accra, Ghana. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 26, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frausto-Martínez, O.; Aguilar-Becerra, C.D.; Colín-Olivares, O.; Sánchez-Rivera, G.; Hafsi, A.; Contreras-Tax, A.F.; Uhu-Yam, W.D. COVID-19, storms, and floods: Impacts of tropical storm cristobal in the western sector of the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, A.; Wasson, R.J.; Rouwenhorst, J.; Amaral, A.L. Disaster Risk Reduction, modern science and local knowledge: Perspectives from Timor-Leste. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddighi, H. Trust in Humanitarian Aid from the Earthquake in 2017 to COVID-19 in Iran: A Policy Analysis. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2020, 14, e7–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shammi, M.; Bodrud-Doza, M.; Towfiqul Islam, A.R.M.; Rahman, M.M. COVID-19 pandemic, socioeconomic crisis and human stress in resource-limited settings: A case from Bangladesh. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawangen, A. Rural cooperatives in disaster risk reduction and management: Contributions and challenges. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2022, 31, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, S.; Tunstall, S.; Parker, D.; Faulkner, H.; Howe, J. Risk communication in emergency response to a simulated extreme flood. Environ. Hazards 2007, 7, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansom, G.T.; Aarvig, K.; Sansom, L.; Thompson, C.; Fawkes, L.; Katare, A. Understanding Risk Communication and Willingness to Follow Emergency Recommendations Following Anthropogenic Disasters. Environ. Justice 2020, 14, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpstra, T.; Lindell, M.K.; Gutteling, J.M. Does communicating (flood) risk affect (flood) risk perceptions? results of a quasi-experimental study. Risk Anal. 2009, 29, 1141–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, J.J.; Bradford, R.A.; Bonaiuto, M.; De Dominicis, S.; Rotko, P.; Aaltonen, J.; Waylen, K.; Langan, S.J. Enhancing flood resilience through improved risk communications. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 2271–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperson, R. Four questions for risk communication. J. Risk Res. 2014, 17, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haer, T.; Botzen, W.J.W.; Aerts, J.C.J.H. The effectiveness of flood risk communication strategies and the influence of social networks-Insights from an agent-based model. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 60, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubeck, P.; Kreibich, H.; Penning-Rowsell, E.C.; Botzen, W.J.W.; de Moel, H.; Klijn, F. Explaining differences in flood management approaches in Europe and in the USA—A comparative analysis. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2017, 10, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, C.; Callsen, I.; Kuhlicke, C.; Kelman, I. The role of local stakeholder participation in flood defence decisions in the United Kingdom and Germany. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2018, 11, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsma, E. The development of flood risk management in the United States. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 101, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustillos Ardaya, A.; Evers, M.; Ribbe, L. Participatory approaches for disaster risk governance? Exploring participatory mechanisms and mapping to close the communication gap between population living in flood risk areas and authorities in Nova Friburgo Municipality, RJ, Brazil. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engdahl, E.; Lidskog, R. Risk, communication and trust: Towards an emotional understanding of trust. Public Underst. Sci. 2014, 23, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; He, B.; Ma, M.; Chang, Q.; Li, Q.; Zhang, K.; Hong, Y. A comprehensive flash flood defense system in China: Overview, achievements, and outlook. Nat. Hazards 2018, 92, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; SAGE: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.H.; Xu, H.; Qin, D.Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.H.; Li, H.H.; Bao, S.J. Water cycle evolution in the Haihe River Basin in the past 10,000 years. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2013, 58, 3312–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Huang, Y.-c.; Bai, R.-z.; Chen, A. Regional disaster risk evaluation of China based on the universal risk model. Nat. Hazards 2017, 89, 647–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.; Labadz, J.C.; Smith, A.; Islam, M.M. Barriers to the uptake and implementation of natural flood management: A social-ecological analysis. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2020, 13, 12561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S. The political economy of flood management reform in China. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2018, 34, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, M.K.; Daněk, P. The perception of risk in the flood-prone area: A case study from the Czech municipality. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2018, 27, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkling, B.; Haworth, B.T. Flood risk perceptions and coping capacities among the retired population, with implications for risk communication: A study of residents in a north Wales coastal town, UK. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, T. 3-Community Disaster Resilience. In Disasters and Public Health, 2nd ed.; Clements, B.W., Casani, J.A.P., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 57–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, R.A.; O’Sullivan, J.J.; van der Craats, I.M.; Krywkow, J.; Rotko, P.; Aaltonen, J.; Bonaiuto, M.; De Dominicis, S.; Waylen, K.; Schelfaut, K. Risk perception-issues for flood management in Europe. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 2299–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalambous, K.; Bruggeman, A.; Giannakis, E.; Zoumides, C. Improving Public Participation Processes for the Floods Directive and Flood Awareness: Evidence from Cyprus. Water 2018, 10, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hügel, S.; Davies, A.R. Public participation, engagement, and climate change adaptation: A review of the research literature. WIREs Clim. Change 2020, 11, e645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cori, L.; Bianchi, F.; Sprovieri, M.; Cuttitta, A.; Ruggieri, S.; Alessi, A.L.; Biondo, G.; Gorini, F. Communication and Community Involvement to Support Risk Governance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaddar, S.; Okada, N.; Choi, J.; Tatano, H. What constitutes successful participatory disaster risk management? Insights from post-earthquake reconstruction work in rural Gujarat, India. Nat. Hazards 2017, 85, 111–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClymont, K.; Morrison, D.; Beevers, L.; Carmen, E. Flood resilience: A systematic review. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 1151–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Few, R.; Brown, K.; Tompkins, E.L. Public participation and climate change adaptation: Avoiding the illusion of inclusion. Clim. Policy 2007, 7, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassel, M.A.; Hinsberger, M. Flood partnerships: A participatory approach to develop and implement the Flood Risk Management Plans. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2017, 10, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, S.A.; Trell, E.-M.; Woltjer, J. Emerging citizen contributions, roles and interactions with public authorities in Dutch pluvial flood risk management. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2021, 37, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).