1. Introduction

With the intensification of homogeneous competition in the home appliance consumer market, the complexity and diversity of product design require cross-departmental synergetic innovation. In the current context of sustainable development of enterprises, the advantage of cross-departmental synergetic innovation within the enterprise lies in its ability to promote consistent information sharing, collaboration, and communication among teams, decompose product development into specific tasks, resources, costs, and time, to improve project efficiency, and promote the enterprise to move towards a new stage of sustainable development. Secondly, through research, we aim to promote the efficiency and quality of project execution for home appliance enterprises and provide guarantees for them to enhance their competitiveness and innovation capabilities in the home appliance market. Arising from this, the synergetic design of enterprise projects across departments and the evaluation of organizational efficiency as a systematic and standardized management method are indispensable components of enterprise innovation strategies.

This article explores the adoption of a cross-departmental synergetic design model by household appliance enterprises to maintain market competitiveness and foster positive relationships among project management, social capital, and organizational efficiency. The purpose of this approach is to develop an effective enterprise collaboration system (ECS) to enhance organizational advantages and the efficiency of the enterprise’s collaborative innovation capabilities. In our research, we discuss the factors that affect the quality and efficiency of product output in the context of cross-departmental synergetic design within home appliance enterprises, as well as how to effectively establish relationships between project management, social capital, and organizational efficiency.

The premise of synergetic design innovation is to develop an efficient organizational system. The main existing problem in this context pertains to the need to avoid narrowness within the organization, break down barriers and information silos among departments, replace the previous command-based management model with interactive information sharing in a context of collaborative management, achieve the goal of producing innovation-driven products and services, and promote the maximization and sustainable development of enterprise innovation achievements and efficiency. To achieve these objectives, we employed a structural equation model approach to analyze the relationships between project management, social capital, and organizational efficiency in the cross-departmental synergetic design project management of home appliance enterprises. Finally, relevant improvement suggestions are proposed and can be used as a reference by relevant enterprises, senior management, and other relevant units and personnel.

2. Literature Review

Hermann Haken proposed the concept of synergy (1973) and improved the theoretical framework of synergetics (1977, 1980, 1989, 1995, 1997, 2006) [

1]. Synergetic design is an innovative process, and Peter Gloor (2006, 2008) defined the notion of a collaborative innovation network (CoIN) as a cell team of self-motivated people with a shared vision [

2]. Thomas Kvan argued that when a team collaborates to accomplish tasks that individuals cannot perform, this situation reflects the value of collaboration [

3]. The importance of synergetic design has been discussed in multiple fields, and research on the definition of and relationship models associated with synergetic design has also been conducted. The synergetic design aims to promote improvement and innovation with regard to design issues based on participation by all parties, a process that is collaboratively designed by both service providers and service users [

4]. Gianluca Spina et al. claimed that synergetic design may occur in different forms and that it depends on two background factors: the uncertainty of the design task and the ability to manage information flow [

5].

Maaike Kleinsmann and Rianne Valkenburg (2008) defined synergetic design as the process by which participants from different disciplines share their knowledge of both fields. These authors explored the obstacles and driving factors associated with the ability of multidisciplinary teams to establish a common understanding in the synergetic design process [

5]. Studies have identified obstacles and drivers of synergetic design across three organizational levels: actors, projects, and companies. The effectiveness of creating mutual understanding hinges not just on direct communication but also on project management and organization [

6]. The fact that the cognitive level and execution ability of each participant in synergetic design are equally important cannot be ignored. Maaike Kleinsmann et al. (2005) claimed that a shared understanding and mutual communication could affect the quality of the final product [

7]. In addition, Amoako Gyampah et al. (2021) found that although trust is crucial to the tasks of obtaining information and sharing knowledge among synergetic design participants, the sharing of norms and knowledge is also crucial for cross-departmental project management and success [

8]. Alghababsheh, Mohammad, and David Gallear studied the importance of the social capital dimension in the collaborative practice of socially sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) [

9].

Synergetic design differs from collaborative design in that the former features high task adaptability and can facilitate high-frequency communication, thus allowing the parties involved to obtain more resources, save innovation costs, and obtain more innovation support. In organizations, the importance of synergetic design is often reflected in the improvement of work efficiency, design innovation and quality, and knowledge sharing. Synergetic design can allow the relevant parties to avoid becoming mired in personal thinking and create a shared understanding. Therefore, in the study, synergetic design refers to the formation of a common goal team composed of participants from different professional fields to improve work efficiency and design service quality based on knowledge and information sharing, clear tasks, and responsibilities.

In other words, knowledge related to the problem is generally distributed among stakeholders [

10]. Knowledge sharing helps break patterns of thinking and overcome deadlocks and, thus, has a positive promoting effect on cross-departmental collaborative product research and development in home appliance enterprises.

In the context of synergetic design, social capital, project management, and organizational efficiency are important factors with regard to improving innovation capabilities. Social capital improves organizational performance through consistency in team collaboration [

11] and has positive impacts on organizational creativity and efficiency [

12]. The cross-departmental synergetic design team itself constitutes a project-based organization and implementation environment, which can maximize organizational efficiency. Di Vincenzo and colleagues showed that project performance correlates significantly with the structure of the project’s social capital [

13].

The significance of studying cross-departmental synergetic design in home appliance enterprises lies in the achievement of value creation, which requires collaboration and efficiency throughout the value chain. The challenge of sustainable development for home appliance enterprises involves overcoming the boundaries among departments through cross-departmental synergetic design, integrating technical and nontechnical elements, and ensuring that cross-departmental collaboration and the spread of efficiency within the organization remain orderly [

12].

Sustainable development encompasses more than just environmental concerns; it also pertains to a company’s ability to consistently address and adapt to developmental challenges [

14]. Home appliance enterprises can ensure efficiency, an improved level of quality, and product research and development models that are competitive in the market through cross-departmental synergetic design [

15].

3. Research Hypotheses and Conceptual Models

3.1. Project Management

Project management is a management method that is used to achieve established goals through reasonable resource allocation and coordination within a specific time frame [

16]. It emphasizes the clarity of project objectives, requirements, and constraints, as well as the quality and efficiency of project deliverables [

17]. In projects featuring cross-departmental synergetic design, project management ensures smooth progress and successful completion by promoting “information-information symmetry”, which refers to information exchange and sharing among relevant departments [

18]. Project management promotes information sharing and exchange among relevant departments by providing clear communication channels, effective meetings, and collaborative tools, thereby improving the timeliness and accuracy of information [

19]. Project management also emphasizes “person task adaptation”, which involves assigning suitable employees to projects that are suitable for their skills and abilities to improve the efficiency and quality of project execution. By evaluating employees’ skills and experience, they can be efficiently matched to suitable tasks, thereby enhancing job satisfaction and productivity [

20].

Project management plays a crucial role in cross-departmental synergetic design projects in home appliance enterprises. These synergetic design projects often involve cooperation and coordination among multiple departments and teams; therefore, a strong project management framework is needed to ensure the smooth progress of all work [

21]. Project management can provide clear communication channels, task allocation, and schedule management in this situation, helping teams collaborate efficiently and share information. By implementing project management, home appliance enterprises can coordinate work among different departments more effectively, improve the efficiency and quality of synergetic design projects, and achieve better business results.

3.1.1. Information-Information Symmetry

One important goal of project management in cross-departmental synergetic design projects in home appliance enterprises is to ensure the efficiency of information exchange and sharing among relevant departments [

22], which is referred to in this study as “information-information symmetry”.

In cross-departmental synergetic design projects, different departments and teams must collaborate and coordinate with each other, sharing important information such as project progress, requirements, and decisions [

10]. Effective “information-information symmetry” helps eliminate information silos, improve communication and collaboration efficiency among teams, and thus promote the smooth progress of projects.

However, cross-departmental synergetic design projects in home appliance enterprises face certain difficulties with regard to achieving effective “information-information symmetry”, such as communication and understanding barriers due to different backgrounds and professional fields, cross-departmental information barriers, and the problems of information overload and screening in home appliance enterprises. If these issues can be effectively addressed, information sharing and communication among teams can be promoted, and project collaboration efficiency and the likelihood of successful delivery can be improved [

23].

3.1.2. Human-Task Adaptation

With regard to cross-departmental synergetic design projects in home appliance enterprises, “human task adaptation” is an important factor in project management. Human task adaptation refers to the process of assigning employees with relevant skills and experience to tasks that match their abilities and interests. Members of different departments and teams have different professional backgrounds and skill sets. By ensuring that employees are suitable for project tasks, their strengths can be fully utilized to improve work efficiency and quality [

24]. When employees feel that their skills and abilities are fully utilized, they are more motivated to work and more likely to achieve good work outcomes. In contrast, if employees are assigned tasks that do not match their abilities, they may feel frustrated and dissatisfied, which may lead to a decrease in work efficiency and quality [

25]. In addition, collaboration and coordination among different departments and teams are crucial. Assigning employees with different professional backgrounds and skills to corresponding tasks can promote complementarity among different teams and enhance the effectiveness of cross-departmental collaboration [

26]. This approach helps to break down information silos, promote information sharing and communication among teams, and improve project collaboration efficiency.

3.2. Social Capital

A key driving factor of team achievements is social capital, which is defined as a characteristic of social organizations that promotes cooperative competition and mutual benefits among teams, ultimately promoting team efficiency [

27]. Social capital plays an important role in promoting information sharing, knowledge transfer, and collaboration in project management. Baruch and Lin identified three key factors in social capital: (1) trust (within the team), i.e., the strength of social dependence among peers in the network; (2) social interaction, i.e., structural interactions or connections among individuals in social networks; and (3) a shared vision, which refers to the sharing of resources, such as language, explanations, and ways of thinking, with the goal of promoting effective communication [

27].

First, social capital promotes information sharing and knowledge transfer. In an environment featuring high trust and cooperation, team members are more willing to share important information and professional knowledge, thereby improving the quality and accuracy of decision-making, accelerating problem resolution, and improving project execution efficiency (trust). Second, social capital enhances team collaboration and collaboration capabilities. After establishing trust and cooperative relationships, team members are more likely to coordinate and cooperate in their work, pursuing project goals jointly (social interaction). In addition, social capital is also crucial for the innovative ability of organizations. When team members exhibit high levels of trust and cooperation, they are more willing to share innovative ideas and try new methods [

28]. This atmosphere of innovation and exploration promotes organizational flexibility and creativity, thus helping project teams adapt and innovate more effectively with regard to problem-solving in response to challenges and changes (shared vision). Social capital creates an environment of open communication and feedback that encourages team members to listen to, understand, and respect each other, thereby enhancing team collaboration effectiveness [

29].

Social capital plays an important role in project management and organizational efficiency. Its formation is a long-term process that exhibits specific characteristics and types. Social capital improves project execution efficiency and organizational efficiency by promoting information sharing, collaboration, and innovation [

30]. To maximize the benefits of social capital, leaders and project managers should focus on its cultivation and foster a positive environment for their teams.

3.3. Organizational Efficiency

Organizational efficiency refers to the resource utilization efficiency and productivity level achieved by an organization in the achievement of established goals [

31]. This term focuses on how to maximize the use of limited resources to complete work and ensure the improvement of work quality and customer satisfaction. For home appliance enterprises, organizational efficiency is vital in swiftly responding to market demands, delivering top-quality products and services, and sustaining a competitive edge.

Leiringer and Zhang claimed that organizational capacity (efficiency) stems from two sources: internal development and external acquisition [

32]. Organizations can achieve external acquisition via various channels, including knowledge acquisition [

33], knowledge sharing [

34], and corporate procurement [

35]. These avenues enable rapid capability development. The foundation of the internal capability development perspective is the hypothesis that capabilities, such as task matching degree and information symmetry efficiency, are specific to the organization.

In cross-departmental synergetic design project management in home appliance enterprises, there are close interrelationships among project management, social capital, and organizational efficiency. The effective implementation of project management can promote the establishment and enhancement of social capital, thereby improving organizational efficiency. The existence and development of social capital also contribute to the smooth progress of project management, thereby improving the level of organizational efficiency.

3.4. Model and Hypotheses

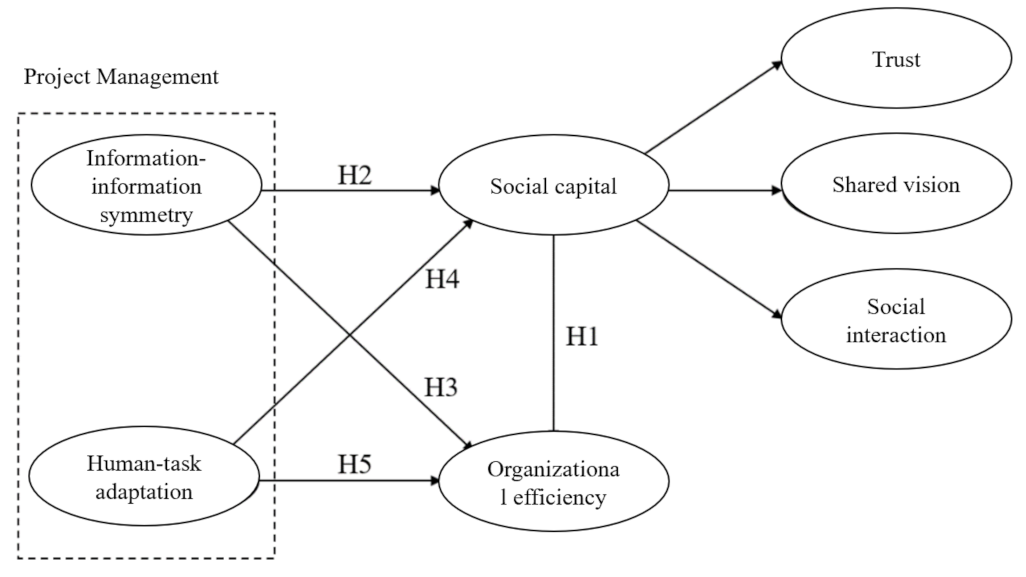

Based on the preceding discussion, this study developed an architecture model (

Figure 1), and the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Social capital positively affects organizational efficiency.

H2: Information-information symmetry positively affects social capital.

H3: Information-information symmetry positively affects organizational efficiency.

H4: Human task adaptation positively affects social capital.

H5: Human task adaptation positively affects organizational efficiency.

Figure 1.

Research structure.

Figure 1.

Research structure.

3.5. Questionnaire Design

This study designed questionnaire items based on the research topic and the relevant literature. The sources of the variable codes, questions, and scales are shown in

Table 1.

3.6. Research Objects

The theme of this study is to explore the relevant role of cross-departmental synergetic design project management in home appliance enterprises. Home appliance enterprises, as key players in contemporary business, have intricate project management needs. This spans from product research and development to technology implementation, marketing, and promotion. Close collaboration among departments and teams is essential for efficient project execution and achieving set goals.

Therefore, for the survey conducted as part of this study, employees from different departments of relevant enterprises were selected to investigate their relevant perceptions. By conducting in-depth research on the roles, impacts, and experiences of relevant employees in cross-departmental synergetic design project management, we can provide valuable insights and suggestions for the improvement of project management practices and organizational efficiency and promote the sustainable development and innovation of home appliance enterprises.

4. Empirical Analyses

4.1. Data Collection

This study was conducted in the form of an online questionnaire that was administered between January and April 2023. In this study, we reached out to several home appliance companies with whom our school has established long-standing partnerships. Upon receiving approval from the executives of these companies, we distributed questionnaires within the respective communities and WeChat groups associated with these businesses. The surveys were completed by the employees and staff members of these home appliance companies. With the exception of basic personal information, all items were scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). All respondents clicked on the website link to the survey questionnaire to view a description of the study. They answered the research questions voluntarily and could withdraw from the survey at any time. Therefore, all participants agreed to complete the questionnaire with full knowledge and voluntary participation.

The final number of observations collected for this study was 700. After excluding invalid responses (those containing logical errors or the same option chosen too many times), the remaining sample included 671 respondents for an effective recovery rate of 95.85%. The questionnaire used in this study included 22 questions, and the sample size of 671 valid responses met Jackson’s criterion that the ratio of estimated parameters to sample size should be higher than 1:10 [

38]. Therefore, subsequent data analysis work was conducted based on this criterion. Statistical analysis was conducted on the data provided by the participants in the valid responses. The statistical results are shown in

Table 2.

The proportion of young people working in home appliance enterprises is relatively high. The data collected in this study align closely with the typical distribution of personnel in such enterprises. Most of the departments at which the test subjects were located were closely involved in design (i.e., the design department, the production technology department, and the marketing department), thus providing preliminary evidence indicating that the test subjects were appropriate for investigating the topics relevant to this study. The reliability and validity testing of the sample in this study is explained in the following section.

4.2. Reliability Analysis

The reliability of the constructs is tested through Cronbach’s α coefficient and the corrected-item-to-total (CITC). As shown in

Table 3, the CITC coefficients of all factors were higher than 0.5. After deleting items, the Cronbach’s α coefficient did not improve significantly, and the Cronbach’s α coefficients of all constructs were all over 0.8, indicating that the internal consistency of the constructs in this study was high, and the data could be used for further analysis.

4.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

While the model and constructs of this study are based on established theories and prior academic work, the questions originated from scales crafted by various scholars. Therefore, it was necessary to use exploratory factor analysis to ensure the structural validity of the measurement model. The questionnaire data were tested using SPSS 22 software, and KMO and Bartlett’s sphericity tests were used to judge whether the questionnaire and scale were suitable for factor analysis. As shown in

Table 4, the KMO value was 0.886, which was significantly higher than the standard of 0.70 [

39]. The Bartlett’s sphericity test shows significant results (

p < 0.05), thus indicating that the model was suitable for factor analysis.

This study then used principal component analysis to measure the distinctiveness and accuracy of the scale dimensions. As shown in

Table 5, factors with eigenvalues greater than were extracted, resulting in a cumulative variance interpretation rate of 69.704%, and the interpretation rates of individual factors were all below 40%. No single factor explained most of the variance, thus meeting Thompson’s criteria [

40]. There was no common method variation in the scale used in this study, and the number of factors matched the dimensions of the preset model in this study.

This study then used principal component analysis to extract new factors from original scale items. As shown in

Table 6, factors with eigenvalues greater than one were extracted, resulting in a cumulative variance interpretation rate of 69.704%, and the interpretation rates of individual factors were all below 40%. No single factor explained most of the variance, thus meeting Thompson’s criteria [

41]. There was no common method variation in the scale used in this study, and the number of factors matched the dimensions of the preset model in this study.

4.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.4.1. Convergent Validity

This study used AMOS v22.0 software to conduct structural equation model analysis. Many studies have employed AMOS for analysis, demonstrating its reliability in structural equation modeling. According to Anderson and Gerbing, data analysis can be divided into two stages [

42]. The first stage is the measurement model, which uses the maximum likelihood estimation method. The estimated parameters include factor loading, reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity and are based on the recommendations from Hair et al. [

43], Nunnally and Bernstein [

44], Fornell and Larcker [

45] concerning convergent validity, and Chin [

46] and Hooper [

47] regarding standardized factor loading, as depicted in

Table 5. In this study, the standardized factor loadings exceeded 0.6, the reliability values of the included factors surpassed 0.7, and the average variance extraction (AVE) values were above 0.5, indicating strong convergent validity [

43] (

Table 7).

Discriminant validity was determined using the criteria set by Fornell and Larcker [

45]. The model exhibits discriminant validity if the square root of the AVE for each construct exceeds its correlation coefficients with other constructs. As demonstrated in

Table 8, all diagonal values in this study exceeded those off the diagonal, confirming the good discriminant validity of each construct.

4.4.2. Model Fit Test

This study selected multiple indicators to evaluate the fit of structural models based on the research conducted by multiple scholars, such as Jackson et al. [

48], Kline [

49], Schumacker [

50], and Hu and Bentler [

51]. Six dimensions were measured according to the research hypotheses and models, as shown in

Table 9 below. All standard model fit evaluation indicators met the level of independence and the combination rules for a recommended fit, proving that the structural model exhibited a good fit. The theoretical framework proposed by the research institute is consistent with the actual results of the survey.

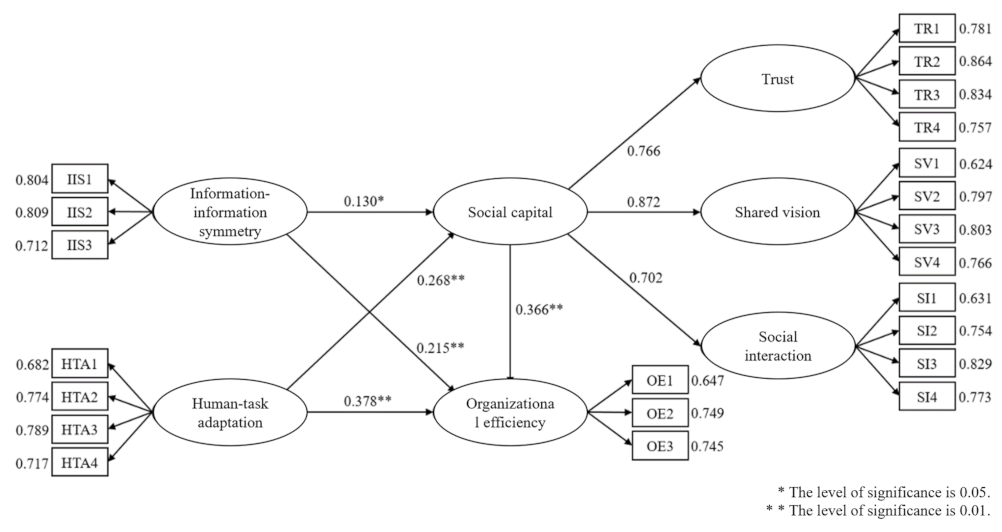

4.5. Path Analysis

Table 10 below shows the results of the path analysis. Organizational efficiency is significantly influenced by human task adaptation (b = 0.368,

p < 0.001), information-information symmetry (b = 0.149,

p < 0.001), and social capital (b = 0.311,

p < 0.001). Social capital is significantly affected by human task adaptation (b = 0.306,

p < 0.001) and information-information symmetry (b = 0.105,

p = 0.044).

Table 10 shows the normalized coefficient of the SEM in this study. A higher coefficient implies that the independent variable has a more important impact on the dependent variable.

Figure 2 shows the influence of the variables in the structural model.

5. Discussion

The validation and verification of the SEM provide some key findings, which are discussed in the following.

H1 focuses on the positive impact of social capital on the organizational efficiency of cross-departmental synergetic design project management in home appliance enterprises, according to employees of the enterprise. This positive relationship between social capital and organizational efficiency is consistent with the results of previous research [

12], thus emphasizing the importance and relevance of social capital with regard to improving the overall performance of such projects. In the context of cross-departmental synergetic design projects, social capital, as a valuable resource, promotes trust, mutual understanding, and a shared vision among team members. This positive work atmosphere encourages open communication, the exchange of ideas, and joint problem-solving, ultimately leading to improved project outcomes. In addition to promoting effective cooperation, social capital also impacts organizational efficiency by simplifying the decision-making process. Stable social connections and shared values within the organization foster a willingness among employees to actively seek opinions and welcome feedback from colleagues.

H2 emphasizes the positive impact of information-information symmetry on the social capital of cross-departmental synergetic design project management in home appliance enterprises, according to employees of the enterprise. Within home appliance enterprises’ cross-departmental synergetic design project management, information-information symmetry is crucial for efficient information exchange and sharing across departments. Employees generally believe that when information-information symmetry is effectively maintained and implemented, information exchange among different departments is smoother and more efficient. This situation helps reduce information asymmetry and overcome information silos, thereby providing team members with more opportunities to understand each other and cultivating social capital to promote mutual trust and understanding.

H3 underscores the consensus among enterprise employees that information-information symmetry positively influences the organizational efficiency of cross-departmental synergetic design project management within home appliance enterprises. This discovery highlights the important role of information-information symmetry in improving project management efficiency. The implementation of information-information symmetry can promote information exchange and sharing among departments, thus ensuring the accuracy and timeliness of information transmission. This approach curtails information lag and misunderstandings, fostering better understanding and streamlined communication among team members and facilitating the project’s smooth progression. By effectively conveying key information, various departments can coordinate resources more effectively, allocate tasks reasonably, and avoid duplicate work. These benefits help reduce resource waste, improve work efficiency, and thus enhance the overall efficiency of the organization.

H4 emphasized the positive impact of human task adaptation on the social capital of cross-departmental synergetic design project management in home appliance enterprises as perceived by employees. Effective task adaptation leads employees to align better with their roles and responsibilities that correspond to their assigned tasks. As employees adeptly adjust to their tasks, their heightened performance often reflects increased professional competence and project responsibility, boosting team cohesion. Furthermore, as employees acclimate to their tasks, their propensity to effectively communicate and collaborate with teammates rises. This collaborative spirit fosters a shared vision, deepens cooperation, and fortifies trust, cultivating social capital in the process.

H5 focuses on the positive impact of human task adaptation on the organizational efficiency of cross-departmental synergetic design project management in home appliance enterprises, according to employees of the enterprise. Human task adaptation helps improve employee job satisfaction and engagement. When employees leverage their strengths and interests, they tend to invest more time and energy, actively driving project progress. This engaged attitude boosts work enthusiasm, directing focus towards task completion and enhancing project efficiency. In addition, the decision-making efficiency of human task adaptation projects is thus promoted. When employees have skills and knowledge that match the task at hand, they can make decisions more quickly, thus reducing uncertainty and hesitation in the decision-making process. This efficient decision-making process helps accelerate project progress, reduce the waste of time and resources, and improve the overall efficiency of project management.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

In this paper, we delve into the intricacies of project management in the context of inter-departmental collaborative design. This perspective has been chosen due to the multi-faceted and intricate business requirements within the home appliance industry. Notably, the development and design of new products necessitate close cooperation among diverse departments. By concentrating on this pivotal aspect, our study introduces novel approaches and recommendations aimed at enhancing project management efficiency and organizational effectiveness for home appliance companies.

This research centers on the nexus between project management, social capital, and organizational efficiency. Through an analysis utilizing structural equation models, we substantiate that information-information symmetry, human-task adaptation, and social capital each play pivotal roles in the management of collaborative design projects within home appliance enterprises. The home appliance sector is characterized by rapid evolution and intense competition, necessitating more effective project management and harnessing social capital to attain sustainable competitive advantages.

Consequently, the findings of this study offer valuable insights to home appliance industry firms on optimizing information exchange, staffing strategies, and social capital cultivation. In conclusion, our study furnishes both theoretical and practical guidance to enterprises. It underscores the significance of bolstering information exchange, refining staffing approaches, and nurturing robust social capital in project management practices. These measures, in turn, can bolster overall efficiency, project management performance, and organizational competitiveness. Our recommendations present a tangible blueprint for success in the ever-evolving market landscape faced by home appliance businesses.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

This study focuses on cross-departmental collaborative design project management in home appliance enterprises, aiming to explore the relationship between project management, social capital, and organizational efficiency. We try to clarify the relationship between the three and analyze social capital and project management as more detailed factors so as to explain the internal perception and related practices of enterprise employees in collaborative design. The results show that project management and social capital are the key factors affecting organizational efficiency, which verifies the importance of collaborative design in the cross-departmental management of home appliance enterprises. In this study, human-task adaptation in project management has the highest impact on organizational efficiency; that is, employees believe that they can maximize their value if they are assigned appropriate tasks. While social capital has a slightly lower impact on organizational efficiency than human-task adaptation, in other words, the importance of social capital represents that research around social capital and its inherent trust, shared vision, and social interaction is of great value. From a theoretical point of view, this study proposes a new deconstruction, connection, and causality between project management, social capital, and organizational efficiency and also provides a theoretical framework for further analysis of cross-departmental collaborative design in the future.

6.3. Practical Implications

The results of this study can be used by relevant enterprises to make relevant adjustments to their personnel allocation structure, planning, etc., with the goals of improving the efficiency of project execution and stimulating the output of results. Therefore, based on the research findings, the following suggestions are proposed for reference:

1. Improving innovation and creativity: Synergetic design promotes knowledge exchange and experience sharing among different departments, enabling teams to view problems from different perspectives and take advantage of their own professional knowledge and creativity. This diversified form of collaboration helps stimulate innovative thinking and generate more forward-looking and competitive design solutions. (1) Knowledge sharing platform: Create a platform for knowledge sharing among employees from various departments, facilitating the exchange of expertise and experiences. This platform can be implemented through internal networks, regular meetings, or online collaboration tools. By encouraging knowledge sharing, employees can draw inspiration from different departments, fostering innovation. (2) Diverse teams: Assemble diverse cross-departmental teams comprising members with distinct backgrounds and expertise. Embracing diversity stimulates a variety of perspectives and creative thinking, thereby yielding more forward-looking and competitive design solutions. (3) Incentivize innovation: Establish a reward system to incentivize employees to propose innovative ideas and translate them into action. Rewards may include bonuses, recognition, and opportunities to lead special projects, among others, designed to motivate employees to actively engage in innovative activities throughout the collaborative design process.

2. Strengthen team cooperation: Synergetic design requires close cooperation and coordination among team members. By jointly participating in the project design and decision-making process, team members can establish closer working relationships, thereby strengthening team cohesion and collaboration efficiency. (1) Training and workshops: Implement team training sessions and workshops to equip employees with essential teamwork skills and effective communication techniques. These initiatives facilitate the development of stronger working relationships and enhance collaboration efficiency. (2) Establishing common goals: Guarantee that all team members possess a clear understanding of the project’s common objectives. Collaboratively formulate measurable goals and key performance indicators (KPIs). This practice ensures that the team remains focused and works collectively toward achieving the project’s success.

3. Improve project execution efficiency: Synergetic design can reduce information isolation and repetitive work, ensure information-information symmetry, and thus accelerate the decision-making and execution process. By optimizing human task adaptation, team members can take full advantage of their professional abilities and improve overall project management efficiency. (1) Information sharing platform: Create a centralized platform for sharing project-related information, enabling all team members to access vital data whenever needed. This approach reduces information disparities and expedites the decision-making process, enhancing overall efficiency. (2) Well-defined task allocation: Establish a clear and concise division of tasks, ensuring that each team member comprehends their responsibilities and duties. Optimizing the alignment between individuals and tasks (man-task fit) allows everyone to leverage their professional expertise, thereby improving project management efficiency.

4. Optimize resource allocation: Synergetic design enables different departments to jointly plan and allocate resources, thereby avoiding resource waste and duplicate investment. This approach helps ensure optimal resource allocation and improve project cost-effectiveness and execution efficiency. (1) Collaborative resource planning: Encourage cross-departmental collaboration in resource planning, encompassing personnel, time, and budget allocation. This collaborative effort ensures the optimal utilization of resources, leading to reduced project costs and enhanced execution efficiency. (2) Performance assessment: Institute a performance evaluation system and conduct regular reviews of resource utilization to pinpoint potential inefficiencies and opportunities for enhancement. This practice facilitates ongoing refinement of resource allocation strategies.

5. Increase project success rates: Synergetic design ensures the project management team has a holistic grasp of project requirements and challenges, facilitating early problem resolution. (1) Early problem resolution: Foster a proactive approach within the project management team, encouraging the early identification and resolution of issues. This approach aims to prevent the accumulation and subsequent delays of problems throughout the project lifecycle. (2) Collaborative project planning: Promote collaborative project planning involving all relevant departments. This inclusive approach enhances the commitment and cooperation of each department, thereby increasing the likelihood of project success.

6.4. Research Limitations and Suggestions

Some limitations of this study may highlight directions for future research:

The research objects explored in this study may have a distribution that is biased towards departments with strong design relevance; however, other departments may also have relevant experience, experience, perceptions, etc., that are relevant to cross-departmental synergetic design project management. Therefore, subsequent research can attempt to expand the research population and obtain more in-depth results;

While this study primarily examines the role of synergetic design in cross-departmental project management for home appliance enterprises, there are still some factors that may not have been explored in depth, and certain related factors might have been overlooked;

The home appliance companies included in this study are predominantly large-scale enterprises based in China. The potential impact of enterprise size variation on the factors under investigation has not been considered. Future researchers may wish to delve deeper into the role of collaborative design in cross-departmental project management within small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs);

This study is a quantitative research paper that uses structural equation modeling as its method of research and analysis. In the future, qualitative research can be conducted to address the deeper meaning of this phenomenon that quantitative data cannot express.