Can Good Government Save Us? Extending a Climate-Population Model to Include Governance and Its Effects

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Data

- The six World Governance Indicators (1996–2020 annual except 1997 and 1999 [2]), originally reported on a scale of −2.5 to 2.5, converted to 0 to 1 indices;

- GDP per capita (GDPPC) in constant U.S. dollars (1990–2019 annual), from which annual GDPPC growth rate (GDPPCGR) was also calculated, as well as the natural logarithm of GDPPC; and

- CO2 emissions per capita in metric tons (1991–2018 annual), from which CO2 intensity of GDP (kilograms per dollar) was also calculated by dividing by GDPPC and multiplying by 1000.

- WGI: On a population-weighted basis across 150 countries, most of the WGI indicators either stayed about the same from 1996 to 2020 or slipped slightly. The worst of these was Stability & Peace, which slipped by 10% in the early 2000s and has remained at this lower level since then. Only Government Effectiveness has improved a bit, by about 6% over the 24-year period.

- GDPPC and GDPPCGR: Global average real GDP per capita grew by about 60% from 1990 to 2020. The annual growth rate has been erratic but generally increased from the 1990s (rising from 0% to 3% per year) to the 2000s (mostly about 3% per year), then declining in the 2010s (mostly 1.5% to 2% per year). The decline may reflect what has been described as the convergence effect [18], in which a country’s economic growth typically slows as its GDPPC climbs to middle or higher income. “Unified growth theory” suggests that convergence across all economies will take place in the long run [19].

- CO2 intensity of GDP: This metric declined steadily throughout 1991–2018, from 0.55 kg/USD2015 in the early 1990s down to 0.42 in the late 2010s, a rate of about 1% per year.

3.2. Statistical Analysis

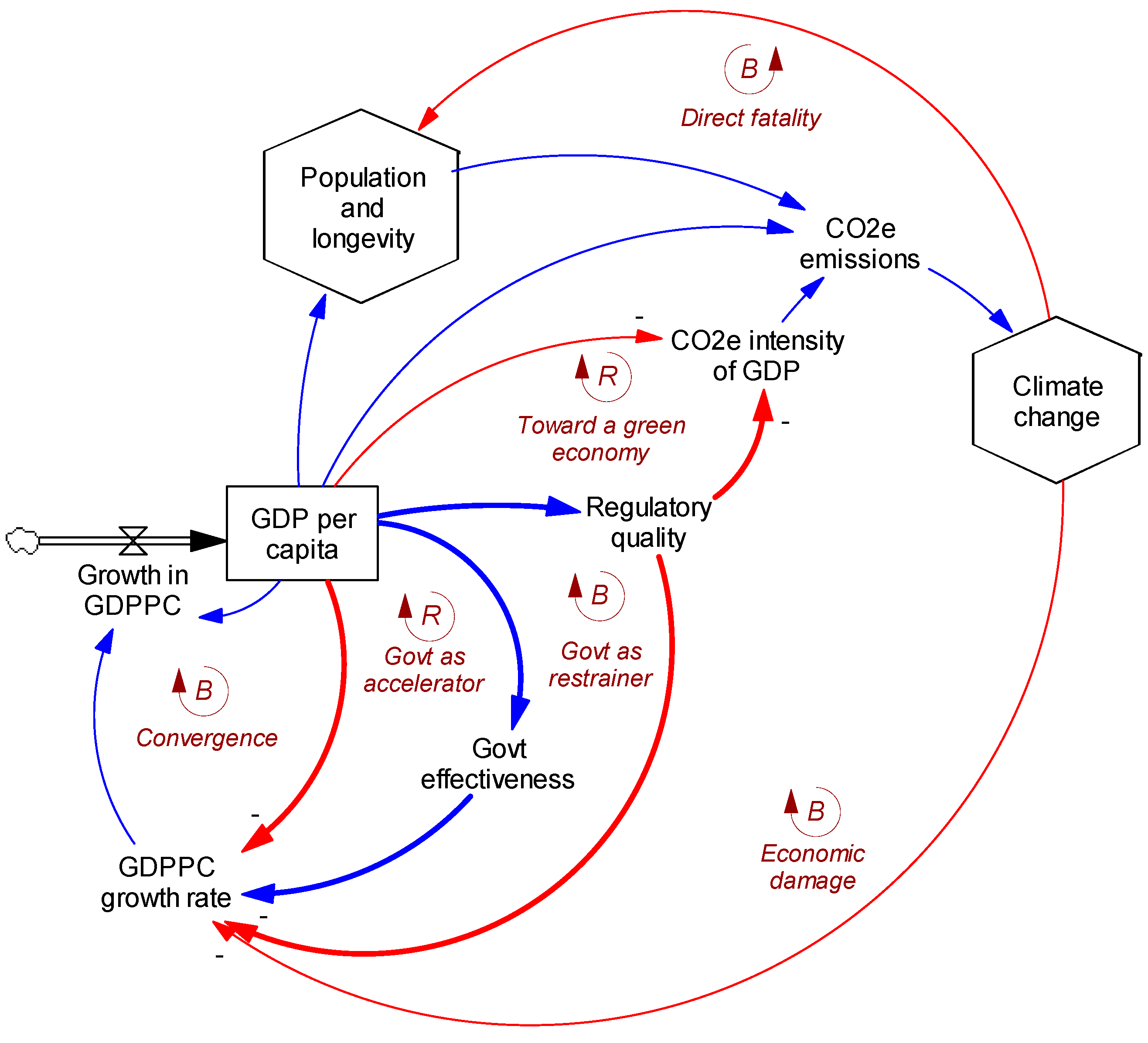

- H1 (for GDPPCGR) was tested initially by including ln(GDPPC) plus all six of the WGI. After winnowing, the strongest equation included ln(GDPPC) with a negative coefficient (thus confirming the convergence effect), Government Effectiveness (GE) with a positive coefficient, and Regulatory Quality (RQ) with a negative coefficient. None of the other four WGI proved significant. H1 is thus partially supported (GE boosts GDPPCGR after controlling for convergence), but we also encounter a surprise (RQ suppresses GDPPCGR).

- Like H1, testing for H2 (for CO2 intensity) initially included ln(GDPPC) plus all six of the WGI. After winnowing, the strongest equation included ln(GDPPC) with a negative coefficient (thus confirming the efficient technologies effect), as well as RQ with a negative coefficient. None of the other five WGI proved significant. H2 is thus supported, with Regulatory Quality revealed as the one aspect of governance in the WGI that predictably reduces CO2 intensity.

- Testing of H3 indicates that ln(GDPPC) is indeed a significant factor (with small p-values) positively affecting both GE and RQ. (Similar results were found for the other four WGI, but these results are irrelevant in light of the H1 and H2 results, which suggested that only GE and RQ should be included in the extended simulation model.)

3.3. Model Revision and Base Run Results

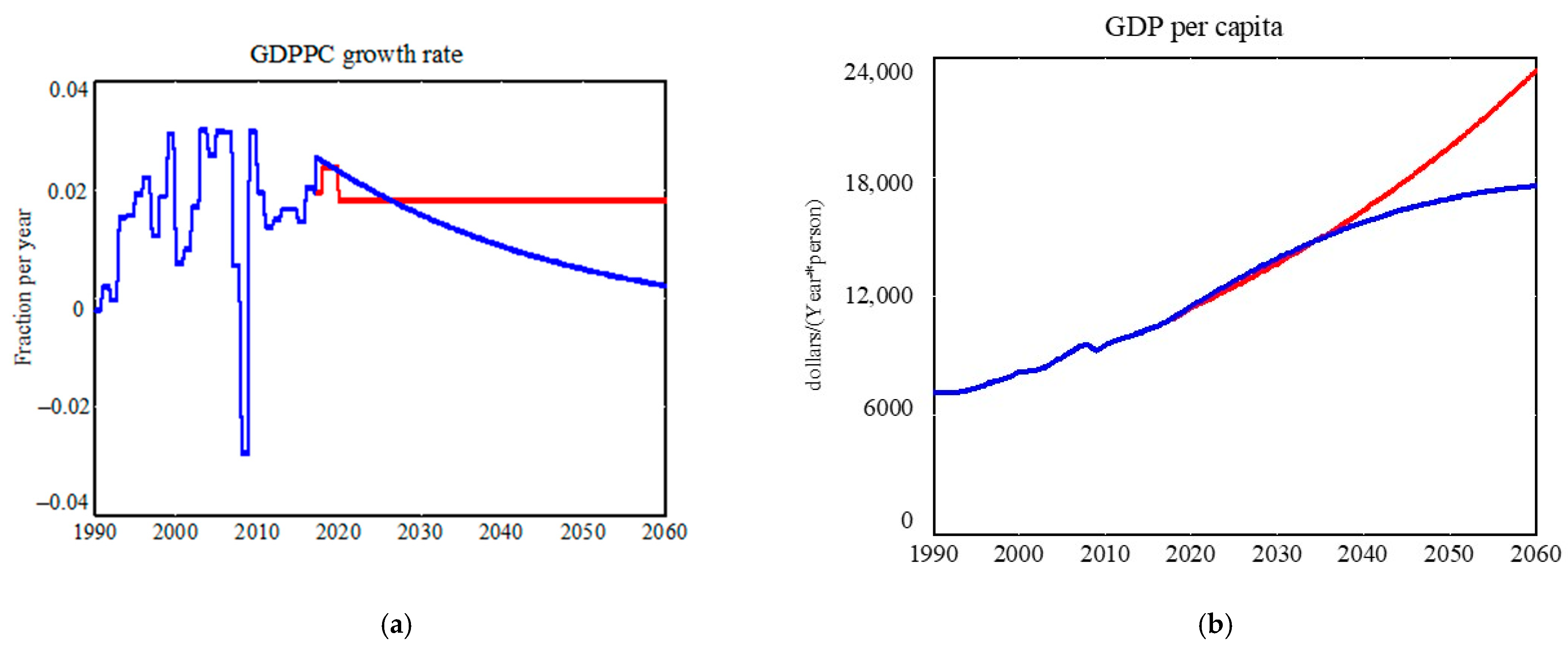

- Equation (1) (GDPPC growth rate): Coefficients for ln(GDDPC), GE, and RQ were adjusted (within ranges suggested by regression H1 in Table 3) to maintain a good fit to baseline projections for global GDPPC [20] through the 2020s and 2030s (Figure 2). The new base run produces a more realistic convergent glide path (blue line; compared with original model red line), with the growth rate declining to 0.2%/year by 2060, similar to that of higher-income countries today. Lower GDPPC in the revised model during 2040–2060 leads, in turn, to lower average life expectancy in 2060 (75.8 vs. 78.1 years). There is virtually no effect on the projection of total population (10.15 vs. 10.14 billion in 2060) because the lower life expectancy is fully offset by a higher birth rate due to lower GDPPC. (For more detail on the projected impacts of changes in GDPPC on life expectancy, birth rate, and total population, see [13]).

- Equations (2) to (4) (Energy CO2 intensity, Non-energy CO2 intensity, Other GHG CO2-equivalent intensity): Coefficients for ln(GDPPC) and RQ were adjusted (as guided by regression H2 in Table 3) to maintain a good fit to baseline projections for these emissions intensities through the 2020s and 2030s (and for CO2e emissions overall) from the En-ROADS model [21]. Beyond 2040, CO2e emissions in the revised model dip slightly below those in the original model, ending in 2060 at 90.4 gigatons per year (revised) compared with 94.1 (original). The impact on projected climate change is very small: temperature above preindustrial (hereafter “temperature delta” in degrees centigrade) in 2060 is 2.54 °C (revised) compared with 2.57 °C (original).

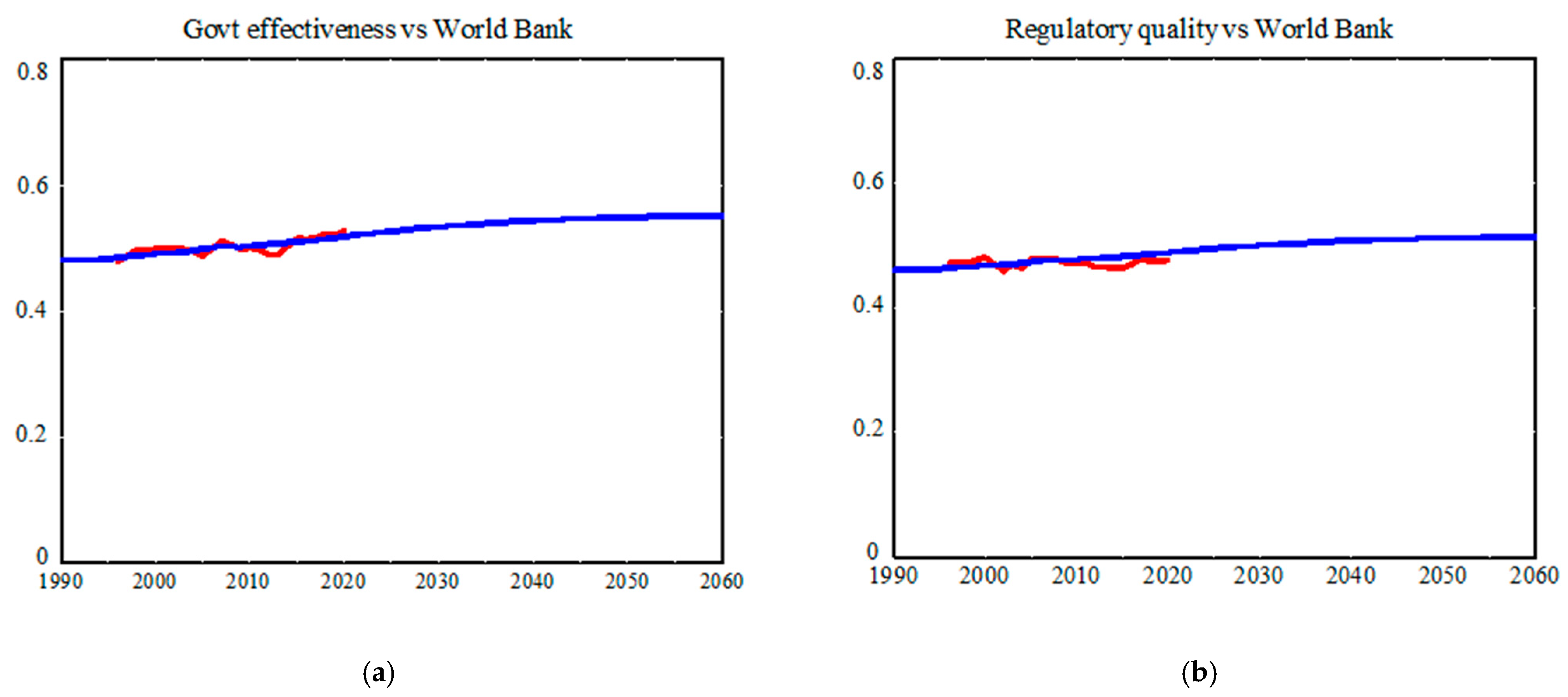

- Equations (5) and (6) (Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality): Coefficients for ln(GDPPC) were adjusted (within ranges suggested by regressions H3 in Table 3) to produce good fits to population-weighted global averages for GE and RQ from 1996 to 2020 (Figure 3). These coefficients are relatively small, so that, although global GDPPC rose by 60% from 1990 to 2020 and in the base run rises another 53% from 2020 to 2060, global GE rises only from 0.48 to 0.52 to 0.55, and global RQ only from 0.46 to 0.49 to 0.51. One may see this same sort of sluggish improvement in GE and RQ at the level of individual countries historically; for example, while India’s GDPPC grew more than threefold from the early 1990s to 2020, its GE grew only from 0.48 to 0.54 and its RQ from 0.42 to 0.45.

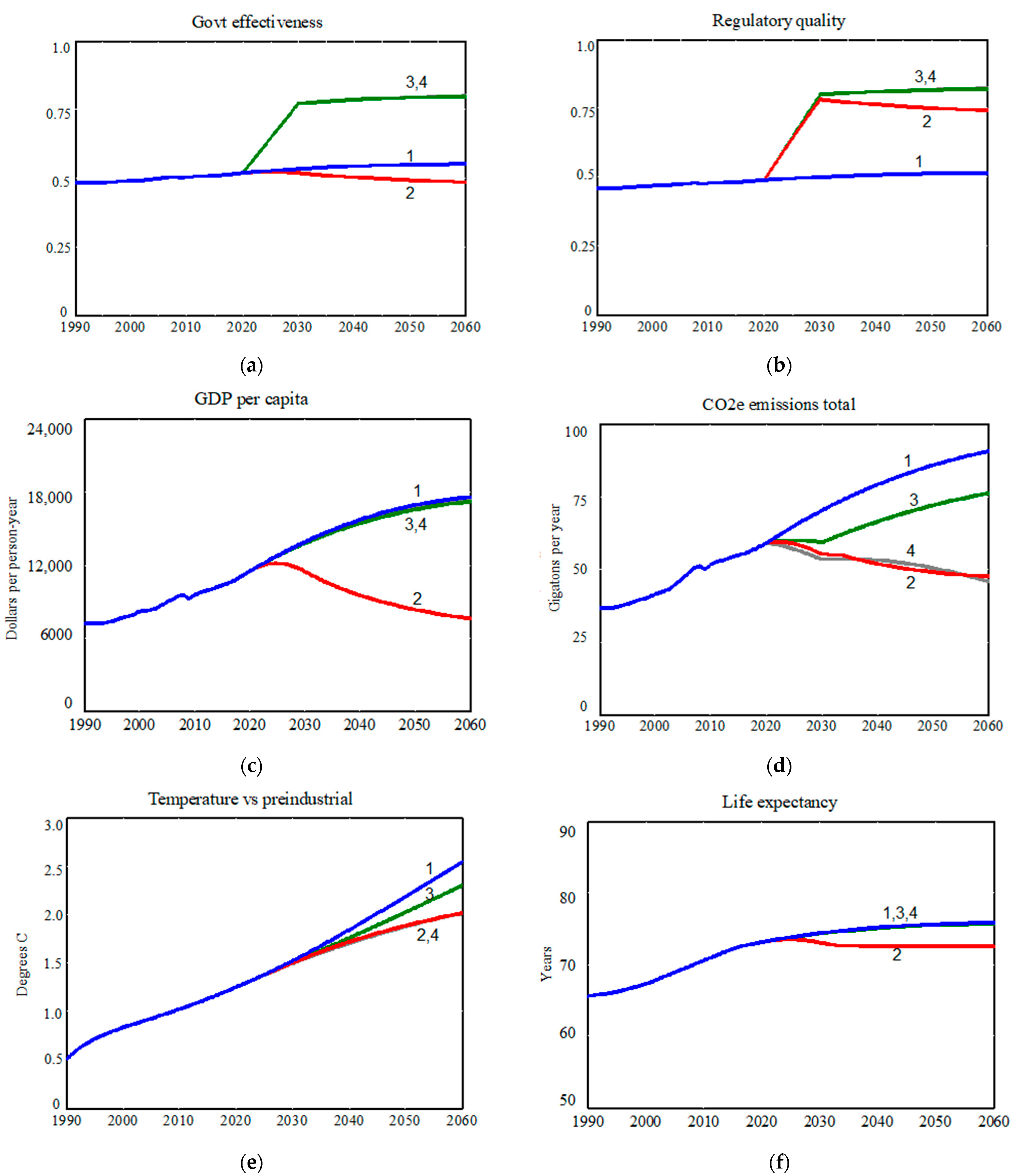

3.4. Policy Testing

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Annex of UN Resolution A/RES/70/1. 2017. Available online: https://ggim.un.org/documents/a_res_71_313.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- World Bank/WGI. Worldwide Governance Indicators Online Database. Available online: https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/ (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Kraay, A.; Zoido-Lobaton, P.; Kaufmann, D. Governance Matters. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. 1999, p. 2196. Available online: https://doi.1596/1813-9450-2196 (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A.; Mastruzzi, M. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: A Summary of Methodology, Data and Analytical Issues. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. 2010, p. 5430. Available online: https://doi.1596/1813-9450-5430 (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Quibria, M.G. Does governance matter? Yes, no, or maybe: Some evidence from developing Asia. Kyklos 2006, 59, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Khan, H.; Zhuang, J. Do Governance Indicators Explain Development Performance? A Cross-Country Analysis; ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 417; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Doucouliagos, H.; Ulubasoglu, M.A. Democracy and economic growth: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 2008, 52, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R. Fast Growth Can Solve Climate Change. 30 November 2015. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/fast-growth-can-solve-climate-change/ (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Cernev, T.; Fenner, R. The importance of achieving foundational Sustainable Development Goals in reducing global risk. Futures 2020, 115, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitz, N.; Carlsen, H.; Nilsson, M.; Skanberg, K. Towards systemic and contextual priority setting for implementing the 2030 agenda. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riahi, K.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Kriegler, E.; Edmonds, J. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: An overview. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 42, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fricko, O.; Havlik, P.; Rogelj, J.; Klimont, Z. The marker quantification of the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 2: A middle-of-the-road scenario for the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 42, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Homer, J. Modeling global loss of life from climate change through 2060. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2020, 36, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, R. Model calibration as a testing strategy for system dynamics models. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2003, 151, 552–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, J.B. Partial-model testing as a validation tool for system dynamcs (1983). Sys. Dyn. Rev. 2012, 28, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collste, D.; Pedercini, M.; Cornell, S. Policy coherence to achieve the SDGs: Using integrated simulation models to assess effective policies. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randers, J.; Rockström, J.; Stoknes, P.-E.; Goluke, U. Achieving the 17 Sustainable Development Goals within 9 planetary boundaries. Glob. Sustain. 2019, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barro, R.J.; Sala-i-Martin, X. Convergence. J. Polit. Econ. 1992, 100, 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galor, O. Unified Growth Theory; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- PriceWaterhouseCoopers (PWC). The World in 2050: Will the Shift in Global Economic Power Continue? 2015. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/the-economy/assets/world-in-2050-february-2015.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Jones, A.P.; Zahar, Y.; Johnston, E.; Sterman, J.D.; Siegel, L. En-ROADS User Guide. Climate Interactive and MIT Sloan Sustainability Initiative. 2019. Available online: https://docs.climateinteractive.org/projects/en-roads/en/latest/index.html (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- van Vuuren, D.P.; Stehfest, E.; Gernaat, D.E.H.J.; Doelman, J.C. Energy, land-use and greenhouse gas emissions trajectories under a green growth paradigm. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 42, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| 1. | Voice and Accountability | Ability of citizens to select their government, plus freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media. |

| 2. | Political Stability and Absence of Violence and Terrorism | Likelihood of political instability and/or politically motivated violence, including terrorism. |

| 3. | Government Effectiveness | Quality of public and civil services (and their independence from political pressures), plus quality of government policy process and credibility of government commitment to such policy. |

| 4. | Regulatory Quality | Formulation and implementation of sound policies and regulations affecting private sector development. |

| 5. | Rule of Law | Quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, plus the likelihood of crime and violence. |

| 6. | Control of Corruption | Minimizing use of public power for private gain, plus avoiding capture of the state by elites and private interests. |

| WGI Ranking for 2015–2020 (N = 150) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voice and Voting | Stability and Non-Violence | Government Effectiveness | Regulatory Quality | Rule of Law | Control of Corruption | |

| China | 142 | 85 | 42 | 80 | 73 | 66 |

| India | 50 | 121 | 52 | 85 | 58 | 69 |

| United States | 23 | 46 | 16 | 17 | 15 | 20 |

| Indonesia | 60 | 98 | 60 | 74 | 78 | 76 |

| Pakistan | 107 | 147 | 105 | 109 | 108 | 114 |

| Brazil | 48 | 94 | 84 | 81 | 68 | 77 |

| Nigeria | 91 | 143 | 131 | 125 | 122 | 131 |

| Bangladesh | 101 | 128 | 119 | 124 | 104 | 122 |

| Russia | 119 | 113 | 71 | 99 | 113 | 120 |

| Japan | 26 | 6 | 11 | 18 | 16 | 16 |

| Mexico | 70 | 114 | 70 | 56 | 97 | 111 |

| Ethiopia | 129 | 136 | 106 | 132 | 91 | 81 |

| Philippines | 65 | 126 | 64 | 70 | 88 | 87 |

| Egypt | 130 | 134 | 99 | 121 | 94 | 99 |

| Vietnam | 137 | 55 | 63 | 90 | 60 | 83 |

| Regressions Maximizing Adjusted R-Squared: Coefficients (1st Row) and p-Values (2nd Row) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Period: | 2000–05 | 2005–10 | 2010–15 | 2015–20 |

| (H1) Y: GDPPC growth rate (N = 150) | ||||

| X1: ln GDPPC | −0.091 | −0.070 | −0.069 | −0.042 |

| p-value | 1 × 10−05 | 2 × 10−05 | 4 × 10−06 | 0.004 |

| X2: Govt Effectiveness | - | 0.206 | 0.176 | 0.118 |

| p-value | ns | 0.014 | 0.039 | 0.189 |

| X3: Reg Quality | - | −0.171 | −0.152 | −0.141 |

| p-value | ns | 0.032 | 0.049 | 0.074 |

| (H2) Y: CO2 intensity of GDP (N = 147) | ||||

| X1: ln GDPPC | −0.600 | −0.681 | −0.648 | −0.508 |

| p-value | 2 × 10−07 | 5 × 10−10 | 4 × 10−09 | 5 × 10−06 |

| X2: Reg Quality | −0.438 | −0.763 | −0.625 | −0.940 |

| p-value | 0.227 | 0.070 | 0.166 | 0.050 |

| (H3) Y: Govt Effectiveness (N = 150) | ||||

| X: ln GDPPC | 0.047 | 0.047 | 0.069 | 0.106 |

| p-value | 0.020 | 0.013 | 1 × 10−04 | 1 × 10−09 |

| (H3) Y: Regulatory Quality (N = 150) | ||||

| X: ln GDPPC | 0.058 | 0.065 | 0.061 | 0.081 |

| p-value | 0.019 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 8 × 10−06 |

| GDPPC growth rate post-2017 = 0.04 − (ln GDPPC ratio to 1990 × 0.04) + (Govt effectiveness delta vs. 1990 × 0.18) − (Regulatory quality delta vs. 1990 × 0.15) − (Temperature delta vs. 2017 × 0.005) | (1) |

| Energy CO2 intensity of GDP post-2017 = 0.412 × (1 − ln GDPPC ratio to 2017 × 0.45) (1 − Regulatory quality delta vs. 1990 × 0.45) | (2) |

| Nonenergy CO2 intensity of GDP post-2017 = 0.092 × (1 − ln GDPPC ratio to 2017 × 0.90) (1 − Regulatory quality delta vs. 1990 × 0.90) | (3) |

| Other GHG CO2e intensity of GDP post-2017 = 0.194 × (1 − ln GDPPC ratio to 2017 × 0.45) (1 − Regulatory quality delta vs. 1990 ∗ 0.45) | (4) |

| Govt effectiveness = 0.48 + (ln GDPPC ratio to 1990 × 0.08) | (5) |

| Regulatory quality = 0.46 + (ln GDPPC ratio to 1990 × 0.05) | (6) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Homer, J. Can Good Government Save Us? Extending a Climate-Population Model to Include Governance and Its Effects. Systems 2022, 10, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10020037

Homer J. Can Good Government Save Us? Extending a Climate-Population Model to Include Governance and Its Effects. Systems. 2022; 10(2):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10020037

Chicago/Turabian StyleHomer, Jack. 2022. "Can Good Government Save Us? Extending a Climate-Population Model to Include Governance and Its Effects" Systems 10, no. 2: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10020037

APA StyleHomer, J. (2022). Can Good Government Save Us? Extending a Climate-Population Model to Include Governance and Its Effects. Systems, 10(2), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10020037