Neuroprotective Effects of Herbal Formula Yookgong-Dan on Oxidative Stress-Induced Tau Hyperphosphorylation in Rat Primary Hippocampal Neurons

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of YGD

2.2. Primary Culture of Rat Hippocampal Neurons

2.3. Experimental Timeline and Workflow

2.4. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) Assay

2.5. Live/Dead Cell Assay

2.6. Immunocytochemistry

2.7. Western Blot

2.8. In Silico Molecular Docking Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. YGD Promotes Cell Survival in H2O2-Stressed Hippocampal Neurons

3.2. YGD Enhances Neurite Outgrowth in H2O2-Stressed Hippocampal Neurons

3.3. YGD Enhances Synaptic Integrity via Increased PSD-95 and Synapsin-1 Expressions

3.4. YGD Enhances Antioxidant Defense via Nrf2 Upregulation and Modulates Stress Response by Reducing Phosphorylated ERK Levels

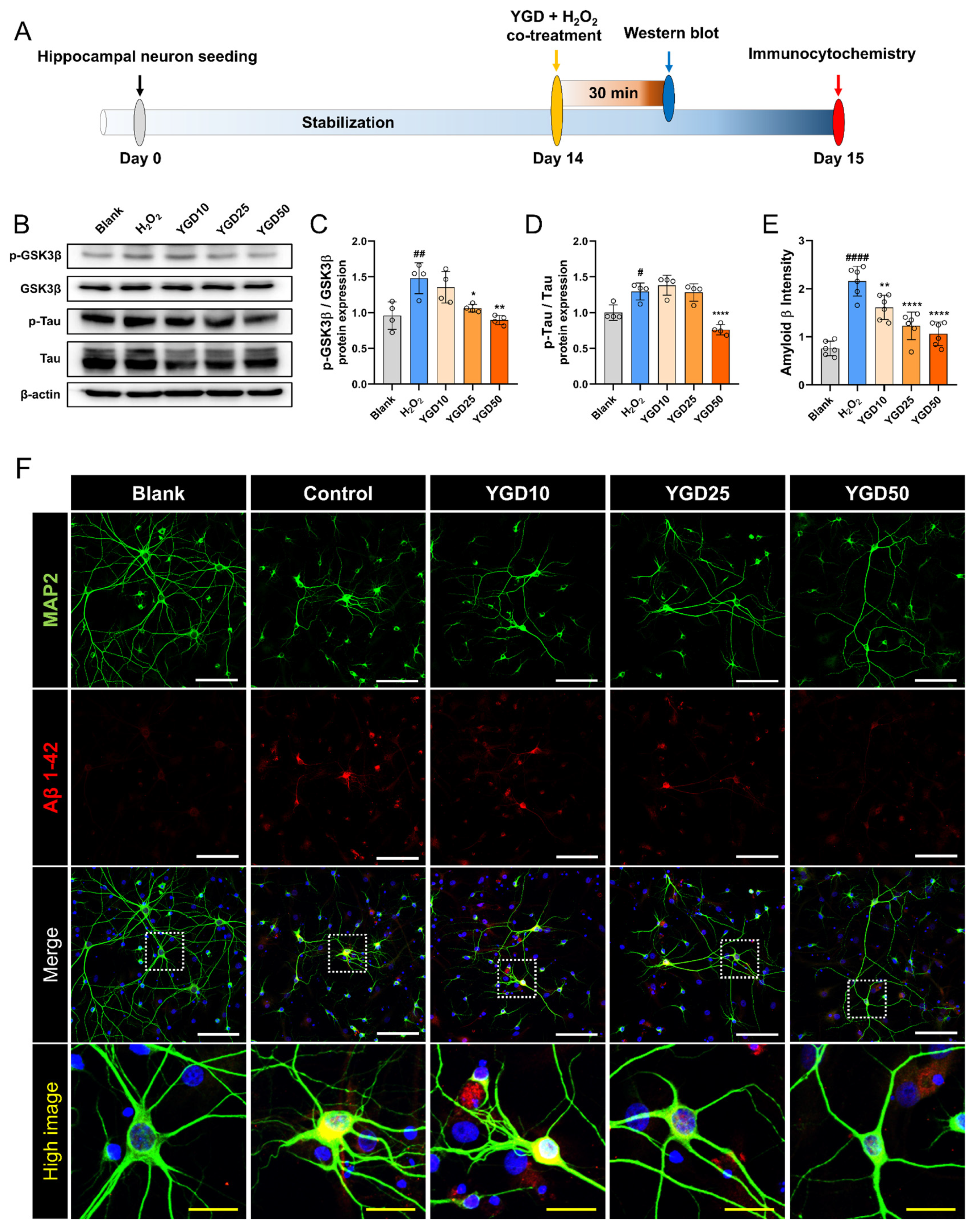

3.5. YGD Attenuates AD-Related Pathological Features by Modulating p-GSK3β, p-tau, and Aβ Expression in H2O2-Stressed Hippocampal Neurons

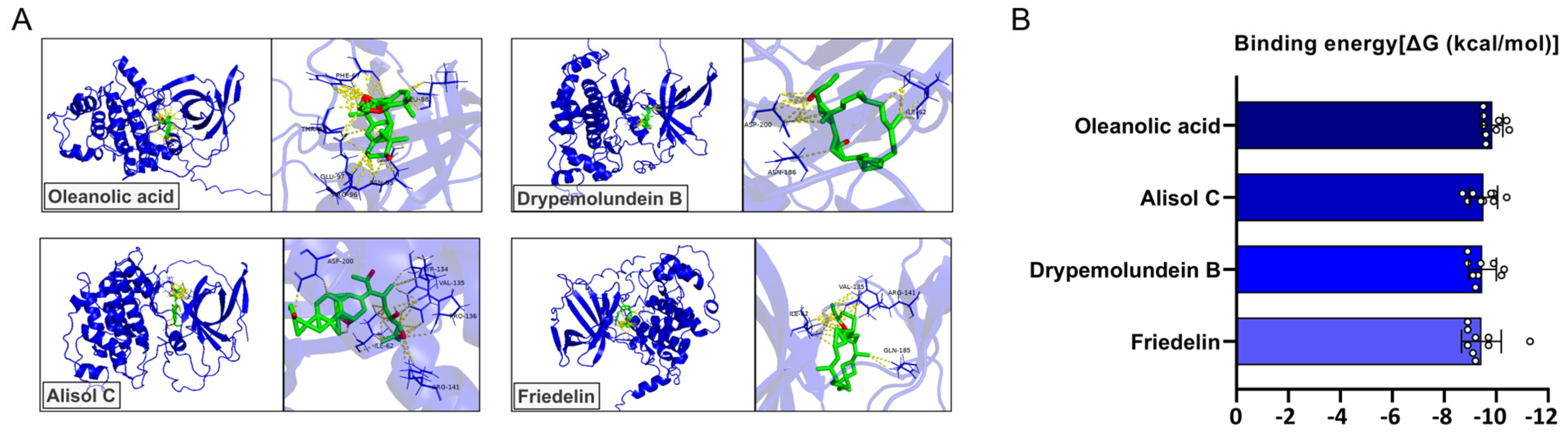

3.6. Molecular Docking Analysis of YGD-Derived Compounds Targeting GSK3β

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aβ | amyloid-β |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| APP | amyloid precursor protein |

| CCK8 | cell counting kit-8 |

| DPBS | Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline |

| ERK | extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| GJD | Gongjin-dan |

| GSK3β | glycogen synthase kinase |

| H2O2 | hydrogen peroxide |

| MAP2 | microtubule-associated protein 2 |

| NFT | neurofibrillary tangle |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor-2 |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| YGD | Yookgong-dan |

| YMJ | Yukmijihwang |

References

- Eichenbaum, H. Amnesia and the Hippocampal Memory System. In The Clinical Neurobiology of the Hippocampus: An Integrative View; Bartsch, T., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, T.; Bird, C.M.; Chan, D.; Cipolotti, L.; Husain, M.; Vargha-Khadem, F.; Burgess, N. The hippocampus is required for short-term topographical memory in humans. Hippocampus 2007, 17, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedayo, L.; Ojo, G.; Umanah, S.; Aitokhuehi, G.; Emmanuel, I.-O.; Bamidele, O. Hippocampus: Its Role in Relational Memory. In Hippocampus; Douglas, D.B., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bailo, P.S.; Martín, E.L.; Calmarza, P.; Breva, S.M.; Gómez, A.B.; Giráldez, A.P.; Callau, J.J.S.-P.; Santamaría, J.M.V.; Khialani, A.D.; Micó, C.C.; et al. The role of oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases and potential antioxidant therapies. Adv. Lab. Med./Av. En Med. De Lab. 2022, 3, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Guo, C.; Kong, J. Oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2012, 7, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedzielska, E.; Smaga, I.; Gawlik, M.; Moniczewski, A.; Stankowicz, P.; Pera, J.; Filip, M. Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 4094–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajmohan, R.; Reddy, P.H. Amyloid-Beta and Phosphorylated Tau Accumulations Cause Abnormalities at Synapses of Alzheimer’s disease Neurons. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 57, 975–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, R.; Sterling, K.; Song, W. Amyloid β-based therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: Challenges, successes and future. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauretti, E.; Dincer, O.; Pratico, D. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2020, 1867, 118664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi Naini, S.M.; Soussi-Yanicostas, N. Tau Hyperphosphorylation and Oxidative Stress, a Critical Vicious Circle in Neurodegenerative Tauopathies? Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 151979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tönnies, E.; Trushina, E. Oxidative Stress, Synaptic Dysfunction, and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 57, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Several lines of antioxidant defense against oxidative stress: Antioxidant enzymes, nanomaterials with multiple enzyme-mimicking activities, and low-molecular-weight antioxidants. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 8416763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallejo, M.J.; Salazar, L.; Grijalva, M. Oxidative Stress Modulation and ROS-Mediated Toxicity in Cancer: A Review on In Vitro Models for Plant-Derived Compounds. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 4586068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Feng, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.; Zhao, R. Melatonin alleviates hippocampal GR inhibition and depression-like behavior induced by constant light exposure in mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 228, 112979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Liu, B.H.; Xie, C.L.; Xia, X.D.; Zhang, Y.M. Neuroprotective effects of N-acetyl cysteine on primary hippocampus neurons against hydrogen peroxide-induced injury are mediated via inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinases signal transduction and antioxidative action. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 6647–6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Kim, W.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, D.; Park, C.H.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, K.T. Stress-induced nuclear translocation of CDK5 suppresses neuronal death by downregulating ERK activation via VRK3 phosphorylation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hong, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Yeo, C.; Jeon, W.J.; Lee, Y.J.; Ha, I.H. Immune-boosting effect of Yookgong-dan against cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppression in mice. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.S.; So, C.S.; Kim, Y.O.; Ahn, D.K.; Sharman, K.G.; Sharman, E.H. The herbal prescription youkongdan modulates rodent memory, ischemic damage and cortical mRNA gene expression. Int. J. Neurosci. 2004, 114, 1365–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, H.W.; Kim, H.G.; Lee, S.K.; Park, B.K.; Son, C.G. The traditional drug Gongjin-Dan ameliorates chronic fatigue in a forced-stress mouse exercise model. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 168, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jeon, W.; Hong, J.; Lee, J.; Yeo, C.; Lee, Y.; Baek, S.; Ha, I. Gongjin-Dan Enhances Neurite Outgrowth of Cortical Neuron by Ameliorating H(2)O(2)-Induced Oxidative Damage via Sirtuin1 Signaling Pathway. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Hong, S.S.; Kim, H.G.; Lee, H.W.; Kim, W.Y.; Lee, S.K.; Son, C.G. Gongjin-Dan Enhances Hippocampal Memory in a Mouse Model of Scopolamine-Induced Amnesia. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M.J.; Im, H.J.; Ku, B.; Lee, J.H.; Jung, S.Y.; Kim, Y.E.; Lee, S.B.; Kim, J.Y.; Son, C.G. An Herbal Drug, Gongjin-dan, Ameliorates Acute Fatigue Caused by Short-Term Sleep-Deprivation: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Clinical Trial. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunwoo, Y.Y.; Park, S.I.; Chung, Y.A.; Lee, J.; Park, M.S.; Jang, K.S.; Maeng, L.S.; Jang, D.K.; Im, R.; Jung, Y.J.; et al. A Pilot Study for the Neuroprotective Effect of Gongjin-dan on Transient Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion-Induced Ischemic Rat Brain. Evid. -Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 682720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kwon, D.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, Y.; Cho, S.H.; Jung, I.C. Efficacy of Yukmijihwang-tang on symptoms of Alzheimer disease: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, e26363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, K.S.; Ma, C.J.; Kim, D.S.; Ma, J.Y. Yukmijihwang-tang inhibits receptor activator for nuclear Factor-kappaB ligand-induced osteoclast differentiation. J. Med. Food 2011, 14, 1439–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I.S.; Lee, M.Y.; Ha, H.K.; Seo, C.S.; Shin, H.K. Inhibitory effect of Yukmijihwang-tang, a traditional herbal formula against testosterone-induced benign prostatic hyperplasia in rats. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.G.; Kim, M.Y.; Cho, J.Y. Alisma canaliculatum ethanol extract suppresses inflammatory responses in LPS-stimulated macrophages, HCl/EtOH-induced gastritis, and DSS-triggered colitis by targeting Src/Syk and TAK1 activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 219, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, B.; Zhang, L.; Gaur, U.; Ma, T.; Jie, H.; Zhao, G.; Wu, N.; Xu, Z.; Xu, H.; et al. The musk chemical composition and microbiota of Chinese forest musk deer males. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Xie, L.; Deng, M.; Zhang, X.; Luo, J.; Li, X. Zoology, chemical composition, pharmacology, quality control and future perspective of Musk (Moschus): A review. Chin. Med. 2021, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Shi, X.; Yang, Q.; Cai, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Bai, X.; Meng, X.; Li, D.; Jie, H. Volatile Compounds in Musk and Their Anti-Stroke Mechanisms. Metabolites 2025, 15, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.M.; Luo, L.; Namani, A.; Wang, X.J.; Tang, X. Nrf2 signaling pathway: Pivotal roles in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Buel, G.R.; Wolgamott, L.; Plas, D.R.; Asara, J.M.; Blenis, J.; Yoon, S.O. ERK2 Mediates Metabolic Stress Response to Regulate Cell Fate. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 382–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khezri, M.R.; Yousefi, K.; Esmaeili, A.; Ghasemnejad-Berenji, M. The Role of ERK1/2 Pathway in the Pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s Disease: An Overview and Update on New Developments. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemmerling, U.; Munoz, P.; Muller, M.; Sanchez, G.; Aylwin, M.L.; Klann, E.; Carrasco, M.A.; Hidalgo, C. Calcium release by ryanodine receptors mediates hydrogen peroxide-induced activation of ERK and CREB phosphorylation in N2a cells and hippocampal neurons. Cell Calcium 2007, 41, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronsato, L.; Boland, R.; Milanesi, L. Testosterone exerts antiapoptotic effects against H2O2 in C2C12 skeletal muscle cells through the apoptotic intrinsic pathway. J. Endocrinol. 2012, 212, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheff, S.W.; Ansari, M.A.; Mufson, E.J. Oxidative stress and hippocampal synaptic protein levels in elderly cognitively intact individuals with Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Neurobiol. Aging 2016, 42, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert-Gasco, H.; Ros-Bernal, F.; Castillo-Gomez, E.; Olucha-Bordonau, F.E. MAP/ERK Signaling in Developing Cognitive and Emotional Function and Its Effect on Pathological and Neurodegenerative Processes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, M.Z.; Pandey, N.R.; Pandey, S.K.; Srivastava, A.K. H2O2-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and PKB requires tyrosine kinase activity of insulin receptor and c-Src. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2005, 7, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Choe, K.; Park, J.S.; Park, H.Y.; Kang, H.; Park, T.J.; Kim, M.O. The Interplay of Protein Aggregation, Genetics, and Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer’s Disease: Role for Natural Antioxidants and Immunotherapeutics. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wei, W.; Zhao, M.; Ma, L.; Jiang, X.; Pei, H.; Cao, Y.; Li, H. Interaction between Abeta and Tau in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 2181–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, C.A.; Sun, Q.; Gamblin, T.C. Tau phosphorylation by GSK-3beta promotes tangle-like filament morphology. Mol. Neurodegener. 2007, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayas, C.L.; Avila, J. GSK-3 and Tau: A Key Duet in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 2021, 10, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, J.M.; Garcia-Rodriguez, S.; Espinosa, J.M.; Millan-Linares, M.C.; Rada, M.; Perona, J.S. Oleanolic Acid Exerts a Neuroprotective Effect Against Microglial Cell Activation by Modulating Cytokine Release and Antioxidant Defense Systems. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; He, J.; Zhang, H.; Yao, L.; Li, H. Oleanolic acid alleviates oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease by regulating stanniocalcin-1 and uncoupling protein-2 signalling. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2020, 47, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, H. Oleanonic acid ameliorates mutant Abeta precursor protein-induced oxidative stress, autophagy deficits, ferroptosis, mitochondrial damage, and ER stress in vitro. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 167459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xia, R.; Jia, J.; Wang, L.; Li, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Oleanolic acid protects against cognitive decline and neuroinflammation-mediated neurotoxicity by blocking secretory phospholipase A2 IIA-activated calcium signals. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 99, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primary Antibody | Source | Vendor | Dilution Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSK3β | Mouse monoclonal | CST | 1:1000 |

| p-GSK3β | Rabbit polyclonal | CST | 1:1000 |

| ERK | Rabbit polyclonal | CST | 1:1000 |

| p-ERK | Rabbit monoclonal | CST | 1:1000 |

| Tau | Guinea pig polyclonal | Synaptic Systems | 1:1000 |

| p-Tau | Mouse monoclonal | Invitrogen | 1:500 |

| β-actin | Mouse monoclonal | Santa Cruz | 1:2000 |

| Herb | Ligand | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | Ki (µM) | pKi | RMSD (Å) | Amino Acid Residue | Hydrogen Bond Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cornus officinalis | Oleanolic acid | −9.86 ± 0.40 | 0.07 ± 0.04 | 7.22 ± 0.30 | 6.32 ± 5.56 | ARG96 ASN95 GLU97 LEU88 PHE67 THR-8 | 5.89 ± 1.54 |

| Alisma canaliculatum | Alisol C | −9.51 ± 0.55 | 0.15 ± 0.13 | 6.97 ± 0.40 | 5.09 ± 2.62 | ARG141 ASP200 ILE62 PRO136 TYR134 VAL135 | 4.89 ± 2.03 |

| Cervi pantotrichum | Drypemolundein B | −9.47 ± 0.54 | 0.15 ± 0.10 | 6.94 ± 0.39 | 4.91 ± 2.35 | ASN186 ASP200 ILE62 | 2.89 ± 1.45 |

| Wolfiporia extensa | Friedelin | −9.43 ± 0.77 | 0.18 ± 0.11 | 6.92 ± 0.56 | 5.24 ± 2.47 | ARG141 GLN185 ILE-62 VAL135 | 2.89 ± 0.93 |

| Dioscorea polystachya | Campestanol | −9.23 ± 0.48 | 0.22 ± 0.15 | 6.77 ± 0.36 | 5.34 ± 3.39 | ARG141 ASP200 GLY68 ILE62 PRO136 TYR134 VAL135 | 4.78 ± 1.20 |

| Angelicae radix | Stigmasterol | −9.17 ± 0.31 | 0.21 ± 0.10 | 6.72 ± 0.23 | 6.60 ± 2.91 | ARG141 ASP200 GLY68 ILE62 PRO136 TYR134 VAL135 | 5.00 ± 2.12 |

| Aquilaria agallocha | 3-epi-Karounidiol | −9.13 ± 0.60 | 0.27 ± 0.15 | 6.70 ± 0.44 | 6.25 ± 5.10 | ASP200 GLN185 ILE62 LYS85 | 4.44 ± 1.13 |

| Musk | Cholesta-3,5-diene | −8.54 ± 0.33 | 0.62 ± 0.34 | 6.26 ± 0.24 | 5.49 ± 2.23 | ASP200 GLN185 ILE62 | 3.11 ± 1.54 |

| Rehmannia glutinosa | Staphidine | −8.02 ± 1.22 | 3.87 ± 3.86 | 5.88 ± 0.90 | 8.37 ± 4.67 | ASP200 GLN185 LYS183 SER66 | 4.67 ± 2.18 |

| Moutan cortex | β-sitosterol | −7.98 ± 0.36 | 1.68 ± 1.10 | 5.85 ± 0.26 | 5.04 ± 3.71 | ASN64 LYS183 VAL135 | 3.89 ± 1.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, H.; Hong, J.Y.; Yeo, C.; Kim, H.; Jeon, W.-J.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.J.; Ha, I.-H. Neuroprotective Effects of Herbal Formula Yookgong-Dan on Oxidative Stress-Induced Tau Hyperphosphorylation in Rat Primary Hippocampal Neurons. Biology 2026, 15, 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15030294

Kim H, Hong JY, Yeo C, Kim H, Jeon W-J, Lee J, Lee YJ, Ha I-H. Neuroprotective Effects of Herbal Formula Yookgong-Dan on Oxidative Stress-Induced Tau Hyperphosphorylation in Rat Primary Hippocampal Neurons. Biology. 2026; 15(3):294. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15030294

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Hyunseong, Jin Young Hong, Changhwan Yeo, Hyun Kim, Wan-Jin Jeon, Junseon Lee, Yoon Jae Lee, and In-Hyuk Ha. 2026. "Neuroprotective Effects of Herbal Formula Yookgong-Dan on Oxidative Stress-Induced Tau Hyperphosphorylation in Rat Primary Hippocampal Neurons" Biology 15, no. 3: 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15030294

APA StyleKim, H., Hong, J. Y., Yeo, C., Kim, H., Jeon, W.-J., Lee, J., Lee, Y. J., & Ha, I.-H. (2026). Neuroprotective Effects of Herbal Formula Yookgong-Dan on Oxidative Stress-Induced Tau Hyperphosphorylation in Rat Primary Hippocampal Neurons. Biology, 15(3), 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15030294