Exploratory Assessment of Short-Term Antecedent Modeled Flow Memory in Shaping Macroinvertebrate Diversity: Integrating Satellite-Derived Precipitation and Rainfall-Runoff Modeling in a Remote Andean Micro-Catchment

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling of Benthic Macroinvertebrates

2.3. Calculation of Benthic Macroinvertebrate Taxonomic Diversity Indices

2.4. Calculation of Benthic Macroinvertebrate Functional Diversity Indices

2.5. Rainfall Data and Rainfall–Runoff Modeling

2.6. Calculation of Antecedent Flow Metrics

2.7. Rationale for Indices Selection

2.8. Data Analysis

Assessing the Most Significant Hydrological Descriptive Parameters

2.9. Hydrological Code and Auxiliary Software

3. Results

3.1. Hydrological Modeling and Flow Characterization

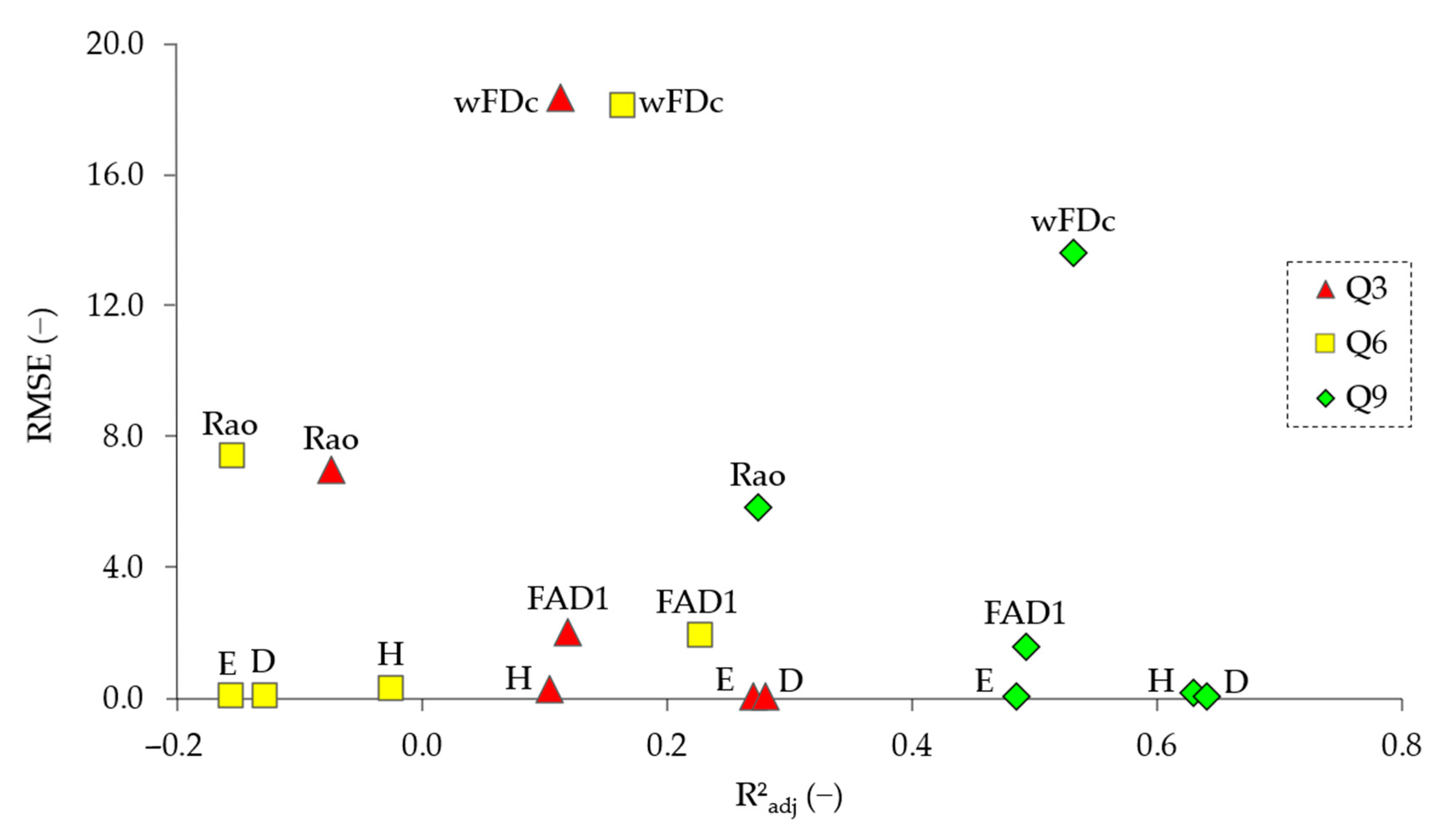

3.2. Exploratory Co-Variation Across Temporal Windows (Q3, Q6, Q9)

3.3. Generalized Additive Models (GAMs)

3.4. Comparative Performance of Taxonomic and Functional Responses Under the Best Temporal Window (Q9)

3.5. Hydrological Parameters Under the Best-Performing Window (Q9)

4. Discussion

4.1. Using Satellite Rainfall Data with Hydrological Modeling

4.2. Optimal Antecedent Window and Ecological Interpretation (Q9)

4.3. Dominant Hydrological Drivers and Ecological Implications

4.4. Taxonomic Versus Functional Sensitivity to Hydrological Variability

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baker, D.B.; Richards, R.P.; Loftus, T.T.; Kramer, J.W. A New Flashiness Index: Characteristics and Applications to Midwestern Rivers and Streams1. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2004, 40, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, D.; Belmar, O.; Maire, A.; Morel, A.; Dumont, B.D. Structural and functional responses of invertebrate communities to climate change and flow regulation in alpine catchments. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 1612–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calapez, A.R.; Serra, S.R.Q.; Rivaes, R.; Aguiar, F.C.; Feio, M.J. Influence of river regulation and instream habitat on invertebrate assemblage’ structure and function. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 794, 148696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalewski, M. Ecohydrology—The use of ecological and hydrological processes for sustainable management of water resources. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2002, 47, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loinaz, M. Integrated Ecohydrological Modeling at the Catchment Scale. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Denmark, Kongens Lyngby, Denmark, 2012. Available online: https://backend.orbit.dtu.dk/ws/files/9891763/Maria_C_Loinazr_PhD_thesis_WWW_Version.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2015).

- Vimos-Lojano, D.J.; Martínez-Capel, F.; Hampel, H.; Vázquez, R.F. Hydrological influences on aquatic communities at the mesohabitat scale in high Andean streams of southern Ecuador. Ecohydrology 2019, 12, e2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenat, D.R. Freshwater Biomonitoring and Benthic Macroinvertebrates. David M. Rosenberg, Vincent H. Resh. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 1993, 12, 220–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoropoulos, C.; Vourka, A.; Skoulikidis, N.; Rutschmann, P.; Stamou, A. Evaluating the performance of habitat models for predicting the environmental flow requirements of benthic macroinvertebrates. J. Ecohydraulics 2018, 3, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munasinghe, D.S.N.; Najim, M.M.M.; Quadroni, S.; Musthafa, M.M. Impacts of streamflow alteration on benthic macroinvertebrates by mini-hydro diversion in Sri Lanka. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, M.; Marchese, M.; Lorenz, G.; Diodato, L. Functional diversity of benthic macroinvertebrates regarding hydrological and land use disturbances in a heavily impaired lowland river. Limnologica 2022, 92, 125940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratan, R.; Venugopal, V. Wet and dry spell characteristics of global tropical rainfall. Water Resour. Res. 2013, 49, 3830–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitterson, J.; Knightes, C.; Parmar, R.; Wolfe, K.; Avant, B.; Muche, M. An Overview of Rainfall-Runoff Model Types. In Proceedings of the 9th International Congress on Environmental Modelling and Software (iEMSs 2018), Fort Collins, CO, USA, 27 June 2018; Paper No. 41. Available online: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/iemssconference/2018/Stream-C/41 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Vázquez, R.F.; Vimos-Lojano, D.; Hampel, H. Habitat suitability curves for freshwater macroinvertebrates of tropical andean rivers. Water 2020, 12, 2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyero, L.; Ramírez, A.; Dudgeon, D.; Pearson, R.G. Are tropical streams really different? J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 2009, 28, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudgeon, D. Tropical Stream Ecology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780120884490/tropical-stream-ecology (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Maggioni, V.; Massari, C. On the performance of satellite precipitation products in riverine flood modeling: A review. J. Hydrol. 2018, 558, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, R.F.; Huffman, G.J.; Keehn, P.R. Global tropical rain estimates from microwave-adjusted geosynchronous IR data. Remote Sens. Rev. 1994, 11, 125–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, B.; Páez-Bimos, S.; Horna, N.; Buytaert, W.; Ochoa-Tocachi, B.; Lavado-Casimiro, W.; Willems, B. Comparative ground validation of IMERG and TMPA at variable spatiotemporal scales in the tropical Andes. J. Hydrometeorol. 2017, 18, 2469–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrat-Capdevila, A.; Merino, M.; Valdes, J.B.; Durcik, M. Evaluation of the Performance of Three Satellite Precipitation Products over Africa. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, L.A.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Pedra, G.U. Assessment of NASA/POWER satellite-based weather system for Brazilian conditions and its impact on sugarcane yield simulation. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamkhi, M.; Jawad, A.; Jameel, T. Comparison between satellite rainfall data and rain gauge stations in galal-badra watershed, Iraq. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Developments in eSystems Engineering, DeSE, Kazan, Russia, 7–10 October 2019; pp. 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheyruri, Y.; Sharafati, A. Spatiotemporal Assessment of the NASA POWER Satellite Precipitation Product over Different Regions of Iran. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2022, 179, 3427–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyeh, H.K.; Mohammed, R. Analysis of NASA POWER reanalysis products to predict temperature and precipitation in Euphrates River basin. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoffin, R.H.; Hales, R.C.; Erazo, B.; Nelson, E.J.; Larco, K.; Miskin, T.J. Evaluating the Performance of Satellite Derived Temperature and Precipitation Datasets in Ecuador. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, A.; Pineda, L.; Crespo, P.; Willems, P. Evaluation of TRMM 3B42 precipitation estimates and WRF retrospective precipitation simulation over the Pacific-Andean region of Ecuador and Peru. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 18, 3179–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erazo, B.; Bourrel, L.; Frappart, F.; Chimborazo, O.; Labat, D.; Dominguez-Granda, L.; Matamoros, D.; Mejia, R. Validation of Satellite Estimates (Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission, TRMM) for Rainfall Variability over the Pacific Slope and Coast of Ecuador. Water 2018, 10, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, M.J.; Müller-Thomy, H.; Nistahl, P.; Šraj, M.; Bezak, N. Validation of precipitation reanalysis products for rainfall-runoff modeling in Slovenia. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 2559–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Q.; Tang, X.; Liu, C.; Jin, J.; Liu, Y.; Bao, Z.; Wang, G. Evaluation of Precipitation Products by Using Multiple Hydrological Models over the Upper Yellow River Basin, China. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimborazo, O.; Vuille, M. Present-day climate and projected future temperature and precipitation changes in Ecuador. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2021, 143, 1581–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, L.R.; Olea, C.E.M. What Drives Take-up in Land Regularization: Ecuador’s Rural Land Regularization and Administration Program, Sigtierras. J. Econ. Race Policy 2020, 3, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajjali, W. ArcGIS for Environmental and Water Issues; Springer Textbooks in Earth Sciences, Geography and Environment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrón, R.S.; Wilcox, B.P.; Crespo, P.; Célleri, R. Rainfall in the Andean Páramo: New Insights from High-Resolution Monitoring in Southern Ecuador. J. Hydrometeorol. 2015, 16, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Ellenrieder, N. Composition and structure of aquatic insect assemblages of Yungas mountain cloud forest streams in NW Argentina. Rev. Soc. Entomol. Argent. 2007, 66, 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Legendre, P.; Legendre, L. Numerical Ecology; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Forio, M.A.E. Statistical Analysis of Stream Invertebrate Traits in Relation to River Conditions. Ph.D. Thesis, Ghent University, Gent, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sotomayor, G. A Functional and Numerical Ecology Approach to Assess the Water Quality of the Rivers in the Paute Basin (Ecuador). Ph.D. Thesis, Ghent University, Gent, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chevenet, F.; Dolédec, S.; Chessel, D. A fuzzy coding approach for the analysis of long-term ecological data. Freshw. Biol. 1994, 31, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotomayor, G.; Hampel, H.; Vázquez, R.F.; Forio, M.A.E.; Goethals, P.L.M. Implications of macroinvertebrate taxonomic resolution for freshwater assessments using functional traits: The Paute River Basin (Ecuador) case. Divers. Distrib. 2021, 28, 1735–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.R. Diversity and dissimilarity coefficients: A unified approach. Theor. Popul. Biol. 1982, 21, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Kinzig, A.; Langridge, J. Plant attribute diversity, resilience, and ecosystem function: The nature and significance of dominant and minor species. Ecosystems 1999, 2, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pla, L.; Casanoves, F.; Di Rienzo, J.; Fernandez, F.; Finegan, B. Confidence intervals for functional diversity indices considering species abundance. In Proceedings of the XXIV International Biometric Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 13–18 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, R.F. Modelación hidrológica de una microcuenca Altoandina ubicada en el Austro Ecuatoriano. Maskana 2010, 1, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.K.; Singh, V.P. Soil Conservation Service Curve Number (SCS-CN) Methodology; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 42. [Google Scholar]

- Soulis, K.X. Soil Conservation Service Curve Number (SCS-CN) Method: Current Applications, Remaining Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Water 2021, 13, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, D.E.; Plummer, A. Antecedent Moisture Conditions: NRCS View Point. In Proceedings of the Watershed Management and Operations Management 2000, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 20 June 2004; Volume 105, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.M.; Ghumman, A.R.; Ahmad, S. Estimation of Clark’s instantaneous unit hydrograph parameters and development of direct surface runoff hydrograph. Water Resour. Manag. 2009, 23, 2417–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poff, N.L.R.; Allan, J.D.; Bain, M.B.; Karr, J.R.; Prestegaard, K.L.; Richter, B.D.; Sparks, R.E.; Stromberg, J.C. The natural flow regime: A paradigm for river conservation and restoration. BioScience 1997, 47, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, B.D.; Baumgartner, J.V.; Powell, J.; Braun, D.P. A Method for Assessing Hydrologic Alteration within Ecosystems. Conserv. Biol. 1996, 10, 1163–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olden, J.D.; Poff, N.L. Redundancy and the choice of hydrologic indices for characterizing streamflow regimes. River Res. Appl. 2003, 19, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytle, D.A.; Poff, N.L.R. Adaptation to natural flow regimes. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, S.P.; Cole, F.A. Taxonomic Level Sufficient for Assessing a Moderate Impact on Macrobenthic Communities in Puget Sounds Washington, USA. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1992, 49, 1184–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, S.P.; Cole, F.A. Taxonomic level sufficient for assessing pollution impacts on the southern California Bight macrobenthos-revisited. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. Int. J. 1995, 14, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Corbi, J.J.; Trivinho-Strixino, S. Influence of taxonomic resolution of stream macroinvertebrate communities on the evaluation of different land uses. Acta Limnol. Bras. 2006, 18, 469–475. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258910023_Influence_of_taxonomic_resolution_of_stream_macroinvertebrate_communities_on_the_evaluation_of_different_land_uses (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Mueller, M.; Pander, J.; Geist, J. Taxonomic sufficiency in freshwater ecosystems: Effects of taxonomic resolution, functional traits, and data transformation. Freshw. Sci. 2013, 32, 762–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, T.; Doretto, A.; Levrino, M.; Fenoglio, S. Contribution of beta diversity in shaping stream macroinvertebrate communities among hydro-ecoregions. Aquat. Ecol. 2020, 54, 957–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D. Hydrology and change. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2013, 58, 1177–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, H.K.; Westerberg, I.K.; Krueger, T. Hydrological data uncertainty and its implications. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2018, 5, e1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, Z.; Buizza, R. Weather Forecasting: What Sets the Forecast Skill Horizon? In Sub-Seasonal to Seasonal Prediction: The Gap Between Weather and Climate Forecasting; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 17–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, I.E.; Todeschini, R. The Data Analysis Handbook; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; Volume 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. BMJ 2014, 349, g7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.J. Generalized Additive Models. In Statistical Models in S; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 249–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stegmann, G.; Jacobucci, R.; Harring, J.R.; Grimm, K.J. Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Modeling Programs in R. Struct. Equ. Model. 2018, 25, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, J.O.; Pantula, S.G.; Dickey, D.A. Applied Regression Analysis: A Research Tool, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson, T.O. Root-mean-square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE): When to use them or not. Geosci. Model. Dev. 2022, 15, 5481–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An Analysis of Variance Test for Normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, P.W., Jr.; Berry, K.J.; Landsea, C.W.; Gray, W.M. A Single-Sample Estimate of Shrinkage in Meteorological Forecasting. Weather Forecast. 1997, 12, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisberg, S. Applied Linear Regression, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; 310p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarboton, D.G.; Bras, R.L.; Rodriguez-Iturbe, I. On the extraction of channel networks from digital elevation data. Hydrol. Process 1991, 5, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanoves, F.; Pla, L.; Di Rienzo, J.A.; Díaz, S. FDiversity: A software package for the integrated analysis of functional diversity. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2011, 2, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, A.H. nasapower: A NASA POWER Global Meteorology, Surface Solar Energy and Climatology Data Client for R. J. Open Source Softw. 2018, 3, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halwatura, D.; Najim, M.M.M. Application of the HEC-HMS model for runoff simulation in a tropical catchment. Environ. Model. Softw. 2013, 46, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador (MAE). Sistema de Clasificación de Ecosistemas del Ecuador Continental; Subsecretaría de Patrimonio Natural—Proyecto Mapa de Vegetación: Quito, Ecuador, 2013.

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolemund, G.; Wickham, H. Dates and Times Made Easy with lubridate. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 40, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, L.J.; Thirel, G.; Harrigan, S.; Delaigue, O.; Hurley, A.; Khouakhi, A.; Prosdocimi, I.; Vitolo, C.; Smith, K. Using R in hydrology: A review of recent developments and future directions. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 2939–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. mgcv: GAMsandGeneralized Ridge Regression for R. R News 2001, 1, 20–25. Available online: https://journal.r-project.org/articles/RN-2001-015/RN-2001-015.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Seibert, J.; Beven, K.J. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences Gauging the ungauged basin: How many discharge measurements are needed? Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2009, 13, 883–892. Available online: www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci.net/13/883/2009/ (accessed on 24 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Morales, M.; Acevedo-Novoa, D.; Machado, D.; Ablan, M.; Dugarte, W.; Dávila, F. Ecohydrology of the Venezuelan páramo: Water balance of a high Andean watershed. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2019, 12, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, V.G.M. Ecohydrology of the Andes Paramo Region; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; 212p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, P.; Liu, X. Evaluation of five satellite-based precipitation products in two gauge-scarce basins on the Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouaba, M.; El Khalki, E.M.; Saidi, M.E.; Alam, M.J.B. Estimation of Flood Discharge in Ungauged Basin Using GPM-IMERG Satellite-Based Precipitation Dataset in a Moroccan Arid Zone. Earth Syst. Environ. 2022, 6, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, U.; Kim, S. Ecohydrologic model with satellite-based data for predicting streamflow in ungauged basins. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildrew, A.; Giller, P. The Biology and Ecology of Streams and Rivers; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2023; 468p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, A.J.; Peterson, C.G.; Grimm, N.B.; Fisher, S.G. Stability of an Aquatic Macroinvertebrate Community in a Multiyear Hydrologic Disturbance Regime. Ecology 1992, 73, 2192–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resh, V.H.; Brown, A.V.; Covich, A.P.; Gurtz, M.E.; Li, H.W.; Minshall, G.W.; Reice, S.R.; Sheldon, A.L.; Wallace, J.B.; Wissmar, R.C. The Role of Disturbance in Stream Ecology. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 1988, 7, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Death, R.G.; Winterbourn, M.J. Diversity Patterns in Stream Benthic Invertebrate Communities: The Influence of Habitat Stability. Ecology 1995, 76, 1446–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthaei, C.D.; Townsend, C.R. Long-term effects of local disturbance history on mobile stream invertebrates. Oecologia 2000, 125, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, P.S. Disturbance, patchiness, and diversity in streams. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 2000, 19, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallaksen, L.M. A review of baseflow recession analysis. J. Hydrol. 1995, 165, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smakhtin, V.U. Low flow hydrology: A review. J. Hydrol. 2001, 240, 147–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolls, R.J.; Leigh, C.; Sheldon, F. Mechanistic effects of low-flow hydrology on riverine ecosystems: Ecological principles and consequences of alteration. Freshw. Sci. 2012, 31, 1163–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piano, E.; Doretto, A.; Mammola, S.; Falasco, E.; Fenoglio, S.; Bona, F. Taxonomic and functional homogenisation of macroinvertebrate communities in recently intermittent Alpine watercourses. Freshw. Biol. 2020, 65, 2096–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanut, P.C.M.; Drost, A.; Siebers, A.R.; Paillex, A.; Robinson, C.T. Flow intermittency affects structural and functional properties of macroinvertebrate communities in alpine streams. Freshw. Biol. 2023, 68, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, C.R.; Hildrew, A.G. Species traits in relation to a habitat templet for river systems. Freshw. Biol. 1994, 31, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosser, Z.C.; Pearson, R.G. Hydrology, hydraulics and scale influence macroinvertebrate responses to disturbance in tropical streams. J. Freshw. Ecol. 2018, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmar, O.; Bruno, D.; Guareschi, S.; Mellado-Díaz, A.; Millán, A.; Velasco, J. Functional responses of aquatic macroinvertebrates to flow regulation are shaped by natural flow intermittence in Mediterranean streams. Freshw. Biol. 2019, 64, 1064–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricotta, C.; de Bello, F.; Moretti, M.; Caccianiga, M.; Cerabolini, B.E.L.; Pavoine, S. Measuring the functional redundancy of biological communities: A quantitative guide. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1386–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, F.C. Taxonomic sufficiency: The influence of taxonomic resolution on freshwater bioassessments using benthic macroinvertebrates. Environ. Rev. 2008, 16, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, Z.; Castro, D.M.; Tan, X.; Jiang, X.; Meng, X.; Ge, Y.; Xie, Z. Effects of different types of land-use on taxonomic and functional diversity of benthic macroinvertebrates in a subtropical river network. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 44339–44353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, V.S.; Siqueira, T.; Bini, L.M.; Costa-Pereira, R.; Santos, E.P.; Pavoine, S. Comparing taxon- and trait-environment relationships in stream communities. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, K.; Zhang, L.; Cai, Y.; Wang, X.; Heino, J. Nutrient enrichment homogenizes taxonomic and functional diversity of benthic macroinvertebrate assemblages in shallow lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2019, 64, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, K.; Choler, P.; de Bello, F.; Mirotchnick, N.; Du, G.; Sun, S. Fertilization decreases species diversity but increases functional diversity: A three-year experiment in a Tibetan alpine meadow. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 182, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trait | Category |

|---|---|

| Feeding habits | Collector-Filterer (C-Ft) |

| Collector-Gatherer (CG) | |

| Piercers (Pc) | |

| Predators (Pr) | |

| Scrapers (Sc) | |

| Shredders (Sh) | |

| Parasite (PA) | |

| Respiration | Tegument (Teg) |

| Gill | |

| Plastron (Pla) | |

| Spiracle (Spi) | |

| Body form | Streamlined (Str) |

| Flattened (Flat) | |

| Cylindrical (Cy) | |

| Spherical (Sph) | |

| Maximum body size (mm) | <2.5 |

| 2.5–5 | |

| 5–10 | |

| 10–20 | |

| 20–40 | |

| 40–80 | |

| Body flexibility (°) | None (<10) |

| Low (10–45) | |

| High (>45) | |

| Locomotion | Flier (Fli) |

| Surface swimmer (SS) | |

| Full water swimmer (FWS) | |

| Crawler (Cra) | |

| Burrower (Bur) | |

| Temporarily attached (TA) | |

| Reproduction | Asexual (As) |

| Clutches and cemented (CC) | |

| Clutches and free (CF) | |

| Clutches in vegetation (CV) | |

| Clutches and Terrestrial (CT) | |

| Isolated eggs and clutches (IEC) | |

| Isolated eggs and free (IEF) | |

| Ovoviviparity (Ovi) | |

| Hardness exoskeleton | None |

| High | |

| Moderate |

| Hydrological Descriptor | Acronym Abbreviation | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean discharge | Qmean | m3 s−1 | Average discharge during the antecedent window, representing overall flow magnitude preceding sampling. |

| Richards–Baker flashiness index | R–B | (−) | Quantifies short-term flow variability as the ratio between the sum of absolute day-to-day discharge changes and total discharge; higher values show more rapid fluctuations. |

| Frequency of positive flow changes | nΔQ > 0 | (−) | Number of instances where discharge increased from one day to the next within the antecedent window, reflecting the frequency of rising flows. |

| Sum of positive flow changes | ΣΔQ > 0 | m3 s−1 | Cumulative magnitude of all positive (increasing) flow changes; represents total intensity of rising-flow events. |

| Sum of negative flow changes | ΣΔQ < 0 | m3 s−1 | Cumulative magnitude of all negative (decreasing) flow changes; represents total intensity of recessional or declining-flow events. |

| Total absolute flow change | Σ|ΔQ| | m3 s−1 |

| Biological Index | Hydrological Parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qmean | RB | nΔQ > 0 | ΣΔQ > 0 | ΣΔQ < 0 | Σ|ΔQ| | |

| H | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.22 | −0.01 |

| E | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.00 |

| FAD1 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| wFDc | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.12 | 0.00 | −0.12 |

| Rao | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sotomayor, G.; Vázquez, R.F.; Eurie Forio, M.A.; Hampel, H.; Erazo, B.; Goethals, P.L.M. Exploratory Assessment of Short-Term Antecedent Modeled Flow Memory in Shaping Macroinvertebrate Diversity: Integrating Satellite-Derived Precipitation and Rainfall-Runoff Modeling in a Remote Andean Micro-Catchment. Biology 2026, 15, 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15030257

Sotomayor G, Vázquez RF, Eurie Forio MA, Hampel H, Erazo B, Goethals PLM. Exploratory Assessment of Short-Term Antecedent Modeled Flow Memory in Shaping Macroinvertebrate Diversity: Integrating Satellite-Derived Precipitation and Rainfall-Runoff Modeling in a Remote Andean Micro-Catchment. Biology. 2026; 15(3):257. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15030257

Chicago/Turabian StyleSotomayor, Gonzalo, Raúl F. Vázquez, Marie Anne Eurie Forio, Henrietta Hampel, Bolívar Erazo, and Peter L. M. Goethals. 2026. "Exploratory Assessment of Short-Term Antecedent Modeled Flow Memory in Shaping Macroinvertebrate Diversity: Integrating Satellite-Derived Precipitation and Rainfall-Runoff Modeling in a Remote Andean Micro-Catchment" Biology 15, no. 3: 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15030257

APA StyleSotomayor, G., Vázquez, R. F., Eurie Forio, M. A., Hampel, H., Erazo, B., & Goethals, P. L. M. (2026). Exploratory Assessment of Short-Term Antecedent Modeled Flow Memory in Shaping Macroinvertebrate Diversity: Integrating Satellite-Derived Precipitation and Rainfall-Runoff Modeling in a Remote Andean Micro-Catchment. Biology, 15(3), 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15030257