Lipid Dependence of CYP3A4 Activity in Nanodiscs

Simple Summary

Abstract

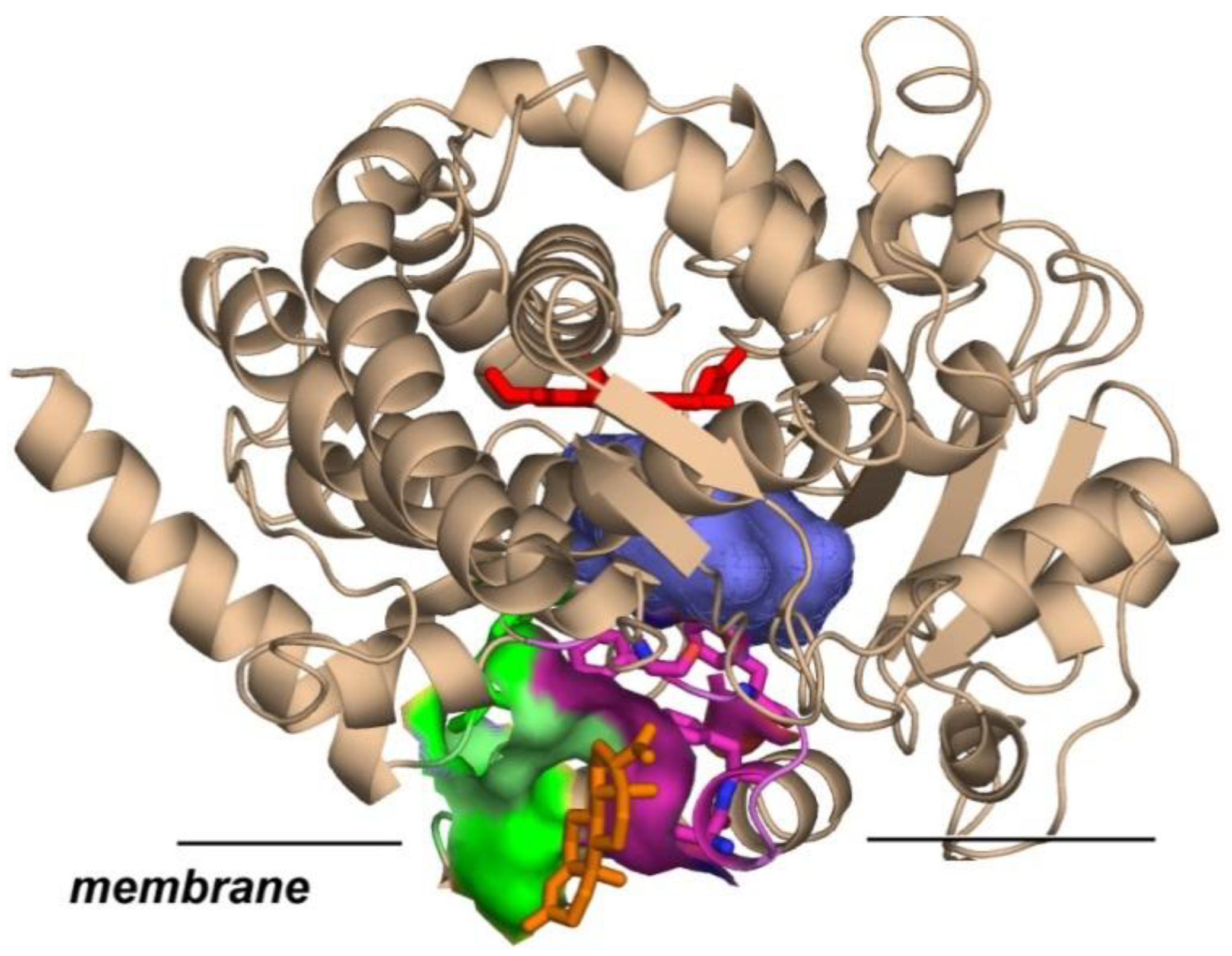

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Protein Expression and Purification

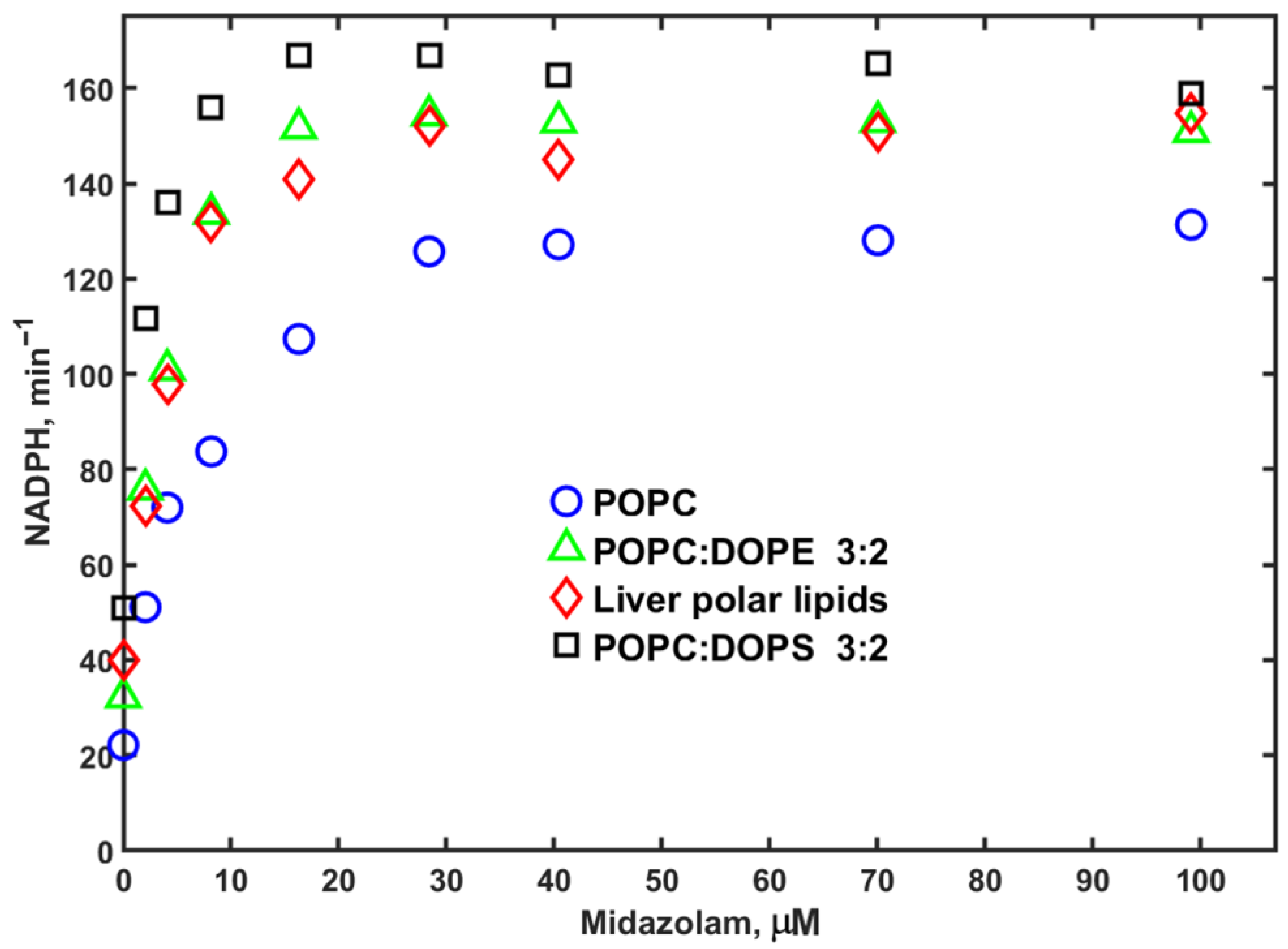

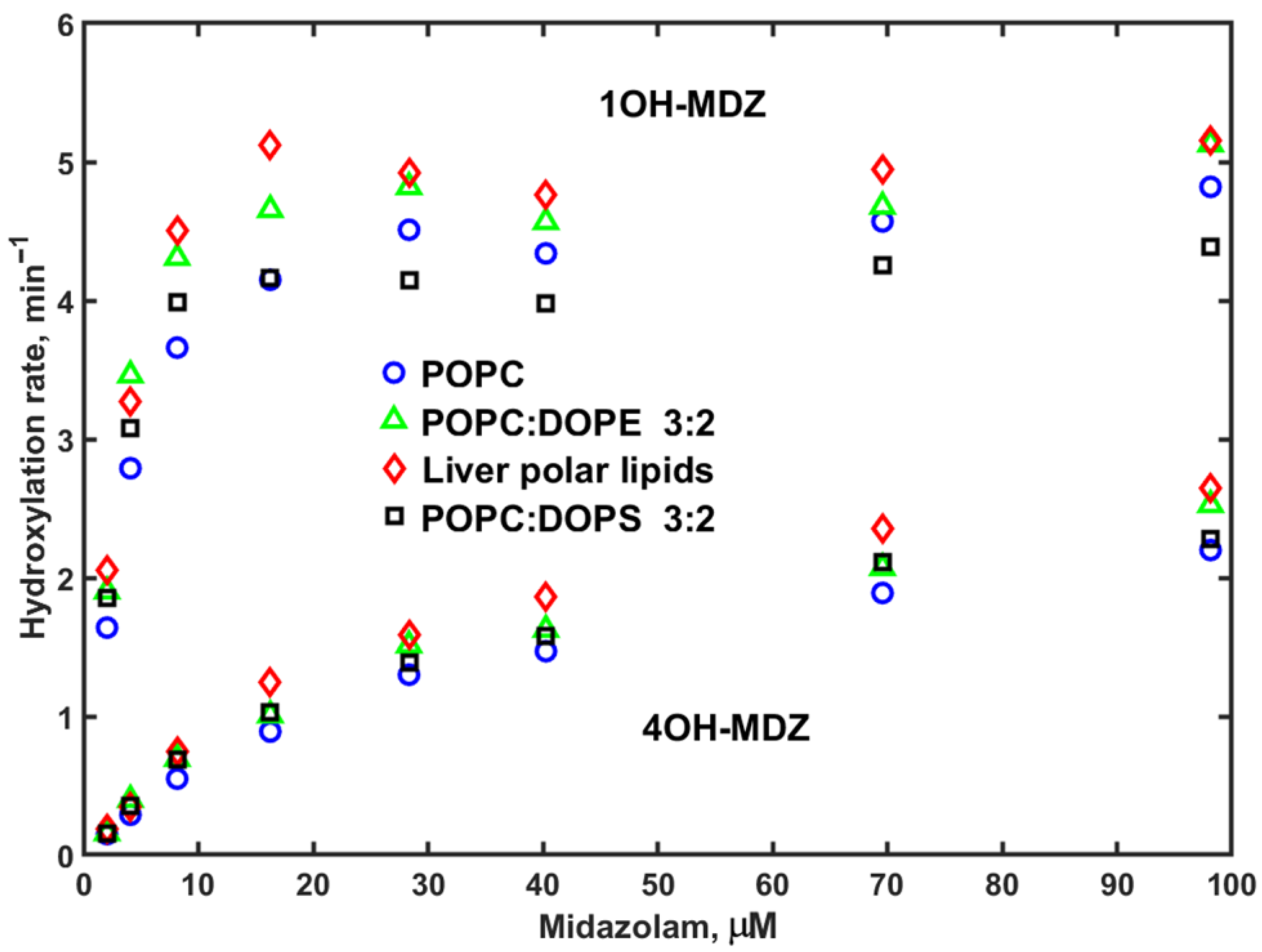

2.2. NADPH Oxidation and Product Formation

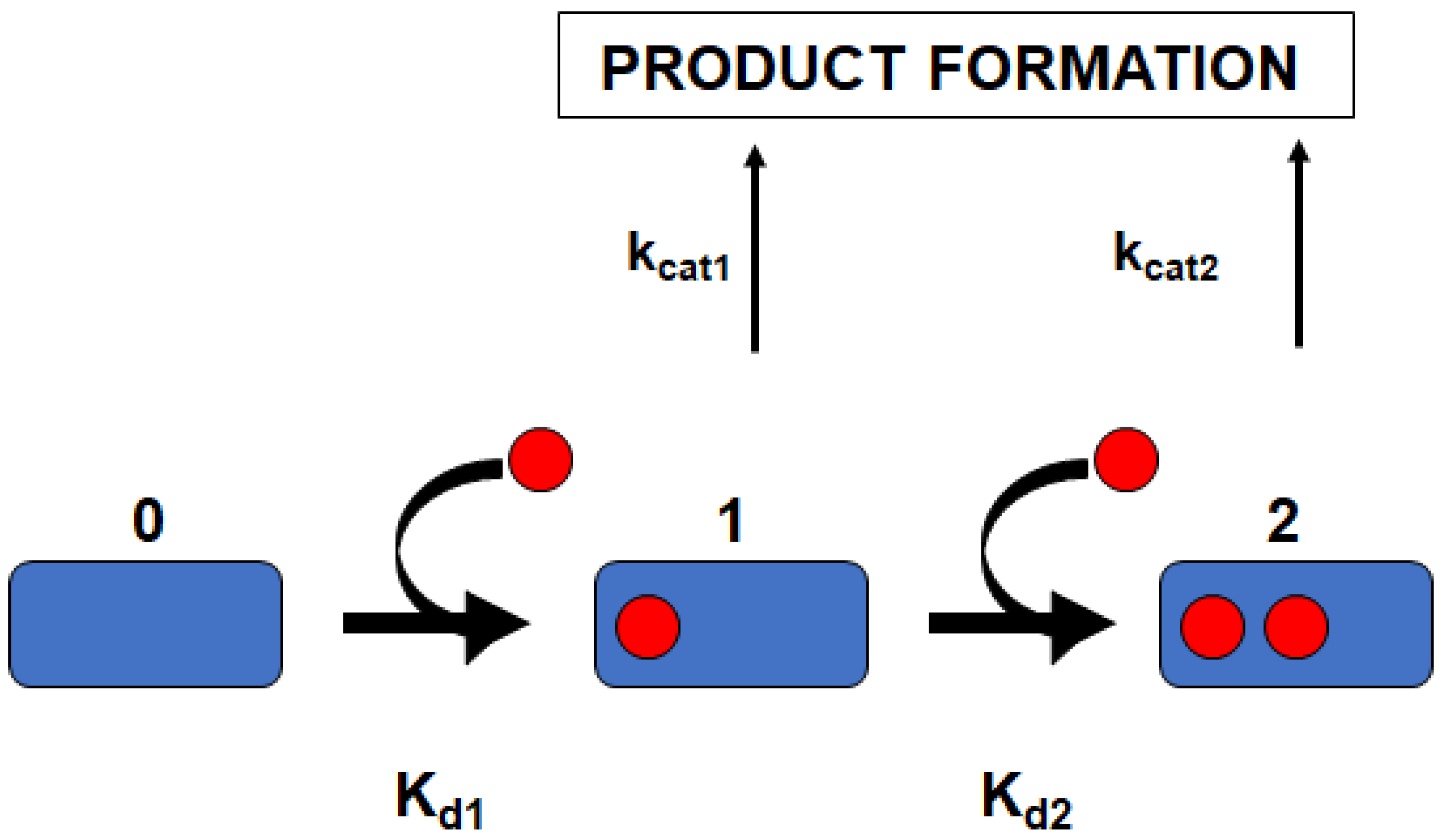

2.3. Global Analysis for Deconvoluting Apparent Cooperative Effects in P450

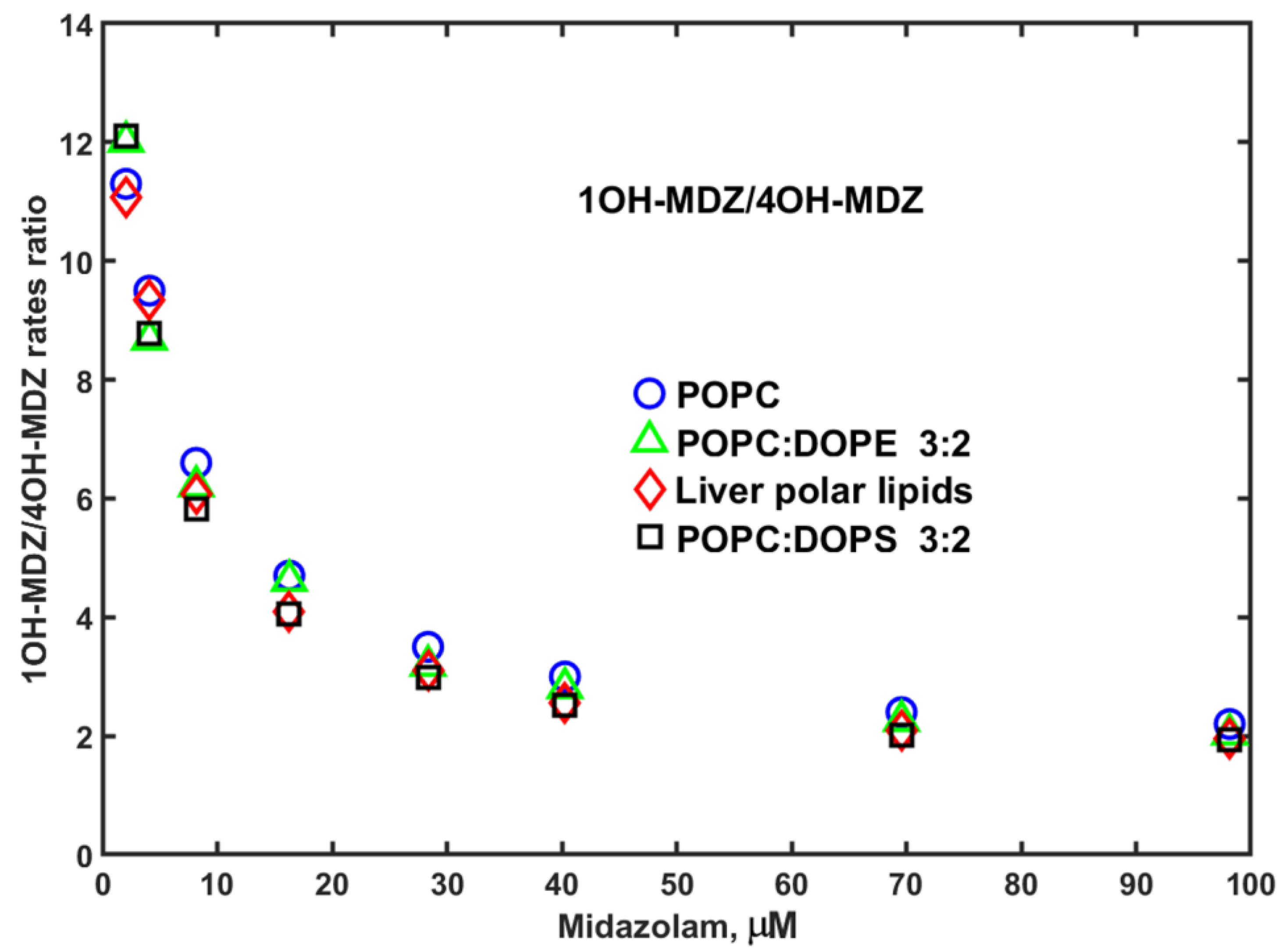

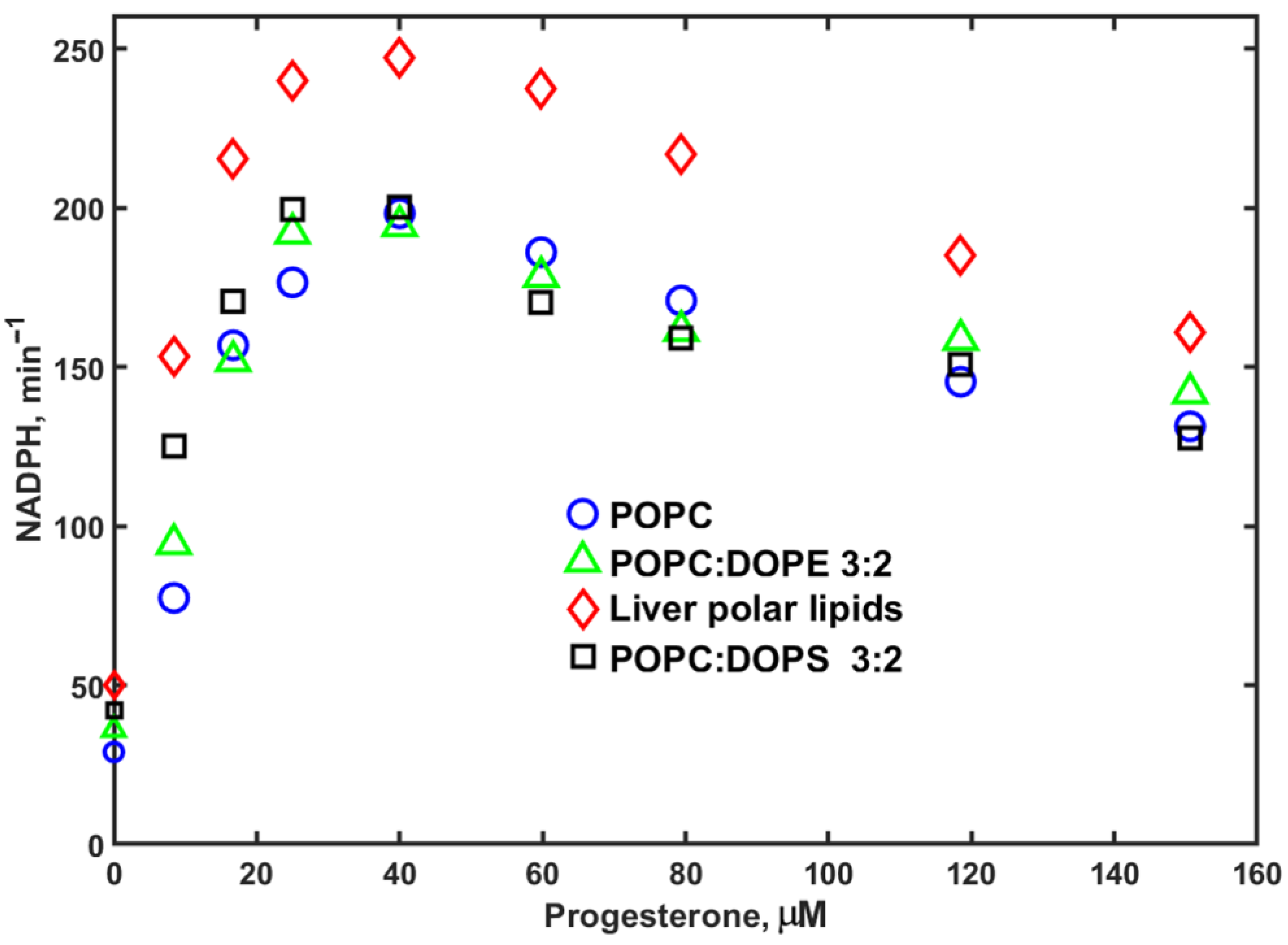

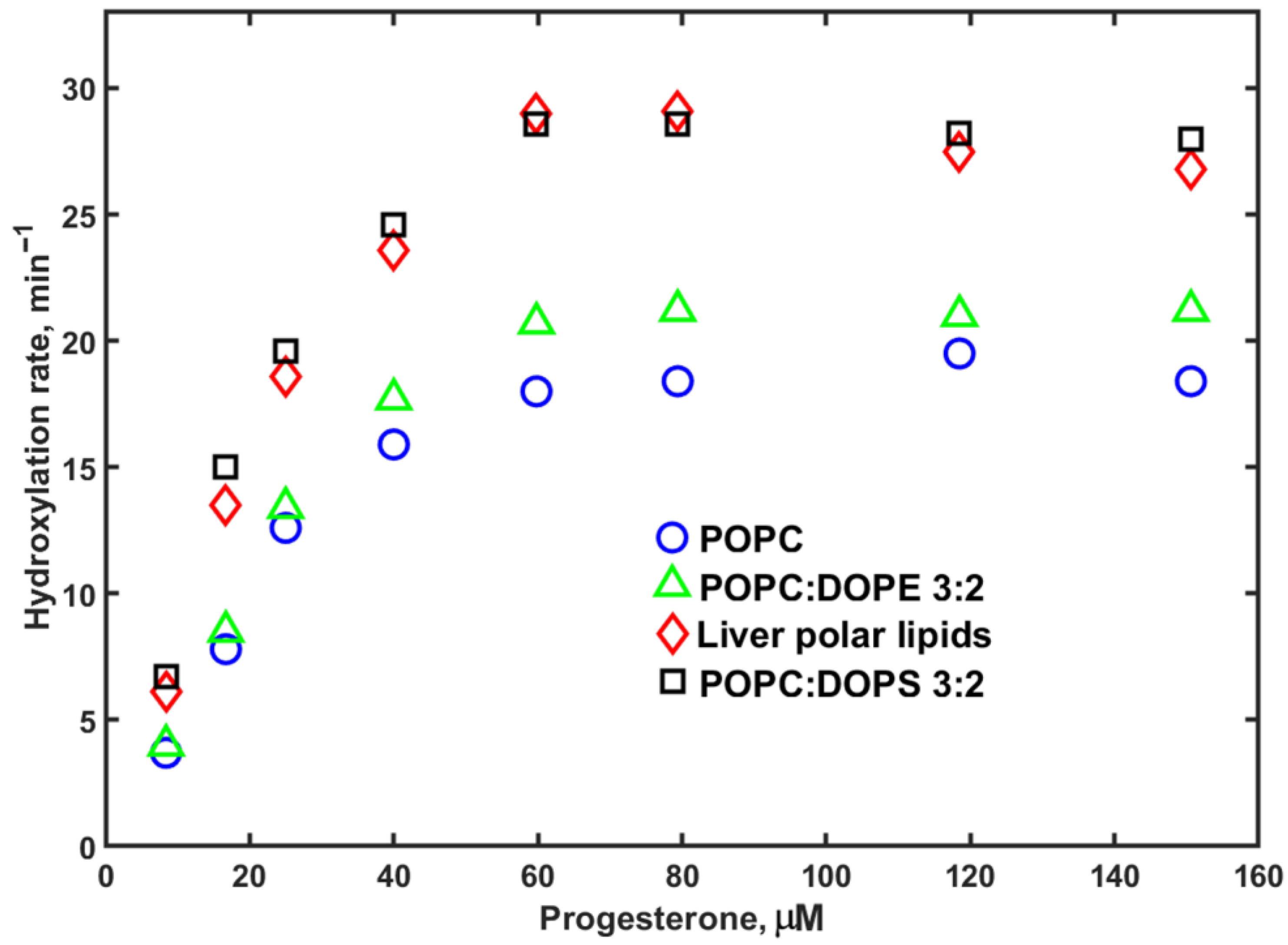

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ekroos, M.; Sjoegren, T. Structural basis for ligand promiscuity in cytochrome P 450 3A4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 13682–13687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevrioukova, I.F.; Poulos, T.L. Understanding the mechanism of cytochrome P450 3A4: Recent advances and remaining problems. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 3116–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guengerich, F.P. Human Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. In Cytochrome P450. Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry, 4th ed.; Ortiz de Montellano, P.R., Ed.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 523–786. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerlin, A.; Trunzer, M.; Faller, B. CYP3A time-dependent inhibition risk assessment validated with 400 reference drugs. Drug Metab. Disp. 2011, 39, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brignac-Huber, L.M.; Park, J.W.; Reed, J.R.; Backes, W.L. Cytochrome P450 Organization and Function Are Modulated by Endoplasmic Reticulum Phospholipid Heterogeneity. Drug Metab. Disp. 2016, 44, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevrioukova, I.F. Interaction of cytochrome P450 3A4 with cannabinoids and the drug darifenacin. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 110709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevrioukova, I.F. Interaction of CYP3A4 with caffeine: First insights into multiple substrate binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 105117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevrioukova, I.F.; Poulos, T.L. Current Approaches for Investigating and Predicting Cytochrome P450 3A4-Ligand Interactions. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015, 851, 83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Denisov, I.G.; Baas, B.J.; Grinkova, Y.V.; Sligar, S.G. Cooperativity in cytochrome P450 3A4: Linkages in substrate binding, spin state, uncoupling, and product formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 7066–7076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisov, I.G.; Frank, D.J.; Sligar, S.G. Cooperative properties of cytochromes P450. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 124, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisov, I.G.; Sligar, S.G. A novel type of allosteric regulation: Functional cooperativity in monomeric proteins. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 519, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisov, I.G.; Baylon, J.L.; Grinkova, Y.V.; Tajkhorshid, E.; Sligar, S.G. Drug-Drug Interactions between Atorvastatin and Dronedarone Mediated by Monomeric CYP3A4. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisov, I.G.; Grinkova, Y.V.; Camp, T.; McLean, M.A.; Sligar, S.G. Midazolam as a Probe for Drug-Drug Interactions Mediated by CYP3A4: Homotropic Allosteric Mechanism of Site-Specific Hydroxylation. Biochemistry 2021, 60, 1670–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisov, I.G.; Grinkova, Y.V.; McLean, M.A.; Camp, T.; Sligar, S.G. Midazolam as a Probe for Heterotropic Drug-Drug Interactions Mediated by CYP3A4. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabrowski, M.J.; Schrag, M.L.; Wienkers, L.C.; Atkins, W.M. Pyrene·Pyrene Complexes at the Active Site of Cytochrome P450 3A4: Evidence for a Multiple Substrate Binding Site. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 11866–11867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, W.M. Non-Michaelis-Menten kinetics in cytochrome P 450-catalyzed reactions. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005, 45, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Atkins, W.M.; Isoherranen, N.; Paine, M.F.; Thummel, K.E. Evidence of CYP3A allosterism in vivo: Analysis of interaction between fluconazole and midazolam. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 91, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinkova, Y.V.; Denisov, I.G.; McLean, M.A.; Sligar, S.G. Oxidase uncoupling in heme monooxygenases: Human cytochrome P450 CYP3A4 in Nanodiscs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 430, 1223–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinkova, Y.V.; Denisov, I.G.; Sligar, S.G. Functional reconstitution of monomeric CYP3A4 with multiple cytochrome P450 reductase molecules in Nanodiscs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 398, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClary, W.D.; Sumida, J.P.; Scian, M.; Paço, L.; Atkins, W.M. Membrane Fluidity Modulates Thermal Stability and Ligand Binding of Cytochrome P4503A4 in Lipid Nanodiscs. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 6258–6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treuheit, N.A.; Redhair, M.; Kwon, H.; McClary, W.D.; Guttman, M.; Sumida, J.P.; Atkins, W.M. Membrane Interactions, Ligand-Dependent Dynamics, and Stability of Cytochrome P4503A4 in Lipid Nanodiscs. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paço, L.; Hackett, J.C.; Atkins, W.M. Nanodisc-embedded cytochrome P450 P3A4 binds diverse ligands by distributing conformational dynamics to its flexible elements. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2023, 244, 112211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, D.T.; Zárate-Pérez, F.; Stokowa-Sołtys, K.; Hackett, J.C. Induced Fit Describes Ligand Binding to Membrane-Associated Cytochrome P450 3A4. Mol. Pharmacol. 2023, 104, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berka, K.; Paloncyova, M.; Anzenbacher, P.; Otyepka, M. Behavior of Human Cytochromes P450 on Lipid Membranes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 11556–11564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackett, J.C. Membrane-embedded substrate recognition by cytochrome P450 3A4. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 4037–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnaba, C.; Ramamoorthy, A. Picturing the Membrane-assisted Choreography of Cytochrome P450 with Lipid Nanodiscs. ChemPhysChem 2018, 19, 2603–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prade, E.; Mahajan, M.; Im, S.C.; Zhang, M.; Gentry, K.A.; Anantharamaiah, G.M.; Waskell, L.; Ramamoorthy, A. A Minimal Functional Complex of Cytochrome P450 and FBD of Cytochrome P450 Reductase in Nanodiscs. Angew. Chem. Intl. Ed. Engl. 2018, 57, 8458–8462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.C.; Hughes, J.M.X.; Hay, S.; Scrutton, N.S. Liver microsomal lipid enhances the activity and redox coupling of colocalized cytochrome P450 reductase-cytochrome P450 3A4 in nanodiscs. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 2302–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.J.; Denisov, I.G.; Sligar, S.G. Mixing apples and oranges: Analysis of heterotropic cooperativity in cytochrome P450 3A4. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2009, 488, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.J.; Denisov, I.G.; Sligar, S.G. Analysis of heterotropic cooperativity in cytochrome P450 3A4 using alpha-naphthoflavone and testosterone. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 5540–5545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisov, I.G.; Grinkova, Y.V.; Baylon, J.L.; Tajkhorshid, E.; Sligar, S.G. Mechanism of drug-drug interactions mediated by human cytochrome P450 CYP3A4 monomer. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 2227–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisov, I.G.; Grinkova, Y.V.; Nandigrami, P.; Shekhar, M.; Tajkhorshid, E.; Sligar, S.G. Allosteric Interactions in Human Cytochrome P450 CYP3A4: The Role of Phenylalanine 213. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 1411–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisov, I.G.; Grinkova, Y.V.; Baas, B.J.; Sligar, S.G. The ferrous-dioxygen intermediate in human cytochrome P450 3A4: Substrate dependence of formation of decay kinetics. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 23313–23318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denisov, I.G.; Grinkova, Y.V.; McLean, M.A.; Sligar, S.G. The one-electron autoxidation of human cytochrome P450 3A4. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 26865–26873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinschmidt, J.H. (Ed.) Lipid-Protein Interactions, 3rd ed.; Humana New York: New York, NY, USA, 2026; Volume 3001. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschmidt, J.H. (Ed.) Lipid-Protein Interactions, 2nd ed.; Springer Science: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschmidt, J.H. (Ed.) Lipid-Protein Interactions: Methods and Protocols; Springer Science: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 974. [Google Scholar]

- Agasid, M.T.; Robinson, C.V. Probing membrane protein-lipid interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2021, 69, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levental, I.; Lyman, E. Regulation of membrane protein structure and function by their lipid nano-environment. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2023, 24, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payandeh, J.; Volgraf, M. Ligand binding at the protein-lipid interface: Strategic considerations for drug design. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 710–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, K.; Byrne, B. Insights into the Role of Membrane Lipids in the Structure, Function and Regulation of Integral Membrane Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradi, V.; Sejdiu, B.I.; Mesa-Galloso, H.; Abdizadeh, H.; Noskov, S.Y.; Marrink, S.J.; Tieleman, D.P. Emerging Diversity in Lipid-Protein Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 5775–5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.J. Electrostatic switch mechanisms of membrane protein trafficking and regulation. Biophys. Rev. 2023, 15, 1967–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisov, I.G.; Schuler, M.A.; Sligar, S.G. Nanodiscs as a New Tool to Examine Lipid-Protein Interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 2003, 645–671. [Google Scholar]

- Sligar, S.G.; Denisov, I.G. Nanodiscs: A toolkit for membrane protein science. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, M.A.; Denisov, I.G.; Sligar, S.G. Nanodiscs as a new tool to examine lipid-protein interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 974, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Denisov, I.G.; Sligar, S.G. Nanodiscs for structural and functional studies of membrane proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016, 23, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denisov, I.G.; Sligar, S.G. Nanodiscs for the study of membrane proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2024, 87, 102844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, M.A.; Gregory, M.C.; Sligar, S.G. Nanodiscs: A Controlled Bilayer Surface for the Study of Membrane Proteins. Ann. Rev. Biophys. 2018, 47, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, M.A.; Stephen, A.G.; Sligar, S.G. PIP2 Influences the Conformational Dynamics of Membrane-Bound KRAS4b. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 3537–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shree, S.; McLean, M.A.; Stephen, A.G.; Sligar, S.G. KRas4b-Calmodulin Interaction with Membrane Surfaces: Role of Headgroup, Acyl Chain, and Electrostatics. Biochemistry 2024, 63, 2740–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.K.; Almurad, O.; Pejana, R.J.; Morrison, Z.A.; Pandey, A.; Picard, L.P.; Nitz, M.; Sljoka, A.; Prosser, R.S. Allosteric modulation of the adenosine A(2A) receptor by cholesterol. eLife 2022, 11, e73901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.K.; Picard, L.P.; Rahmatullah, R.S.M.; Pandey, A.; Van Eps, N.; Sunahara, R.K.; Ernst, O.P.; Sljoka, A.; Prosser, R.S. Mapping the conformational landscape of the stimulatory heterotrimeric G protein. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2023, 30, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gui, M.; Wang, Z.F.; Gorgulla, C.; Yu, J.J.; Wu, H.; Sun, Z.J.; Klenk, C.; Merklinger, L.; Morstein, L.; et al. Cryo-EM structure of an activated GPCR-G protein complex in lipid nanodiscs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2021, 28, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, J.D.; Fielden, L.F.; Pfanner, N.; Wiedemann, N. Mitochondrial protein transport: Versatility of translocases and mechanisms. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 890–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuragi, T.; Nagata, S. Regulation of phospholipid distribution in the lipid bilayer by flippases and scramblases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 576–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Sligar, S.G. Modulation of the cytochrome P450 reductase redox potential by the phospholipid bilayer. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 12104–12112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Grinkova, Y.V.; Sligar, S.G. Redox potential control by drug binding to cytochrome P 450 3A4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 13778–13779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumangala, N.; Im, S.C.; Valentín-Goyco, J.; Auchus, R.J. Influence of cholesterol on kinetic parameters for human aromatase (P450 19A1) in phospholipid nanodiscs. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2023, 247, 112340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, H.C.; Maroutsos, D.; Das, A. Lipid composition and macromolecular crowding effects on CYP2J2-mediated drug metabolism in nanodiscs. Protein Sci. 2019, 28, 928–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| POPC | DOPE 40% | LPL | DOPS 40% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd1, μM | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 1.8 |

| Kd2, μM | 39.1 | 31.8 | 21.5 | 26.1 |

| NADPH v1, min−1 | 119 | 183 | 171 | 194 |

| NADPH v2, min−1 | 140 | 142 | 147 | 151 |

| kcat1, min−1 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 4.3 |

| kcat2, min−1 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.9 | 7.1 |

| 4OH fraction 1, % | 5 | 4 | 1.5 | 1.8 |

| 4OH fraction 2, % | 39 | 40 | 39 | 39 |

| Coupling 1, % | 4.3 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 2.2 |

| Coupling 2, % | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 4.7 |

| POPC | DOPE 40% | LPL | DOPS 40% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd1, μM | 15.5 | 20.3 | 16.9 | 26.4 |

| Kd2, μM | 24.1 | 23.8 | 58.3 | 29.1 |

| Kd3, μM | 26.8 | 26.5 | 64.8 | 34.3 |

| NADPH v1, min−1 | 17 | 129 | 362 | 321 |

| NADPH v2, min−1 | 550 | 437 | 334 | 303 |

| NADPH v3, min−1 | 60 | 89 | 57 | 84 |

| kcat1, min−1 | 0 | 0.4 | 10.3 | 16.9 |

| kcat2, min−1 | 25.9 | 29.7 | 68.8 | 44.0 |

| kcat3, min−1 | 18.3 | 20.5 | 11.6 | 25.1 |

| Coupling 1, % | 0 | 0.3 | 2.8 | 5.3 |

| Coupling 2, % | 4.7 | 6.8 | 20.6 | 14.5 |

| Coupling 3, % | 30.5 | 23.0 | 20.4 | 29.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Denisov, I.G.; Grinkova, Y.V.; Sligar, S.G. Lipid Dependence of CYP3A4 Activity in Nanodiscs. Biology 2026, 15, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020156

Denisov IG, Grinkova YV, Sligar SG. Lipid Dependence of CYP3A4 Activity in Nanodiscs. Biology. 2026; 15(2):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020156

Chicago/Turabian StyleDenisov, Ilia G., Yelena V. Grinkova, and Stephen G. Sligar. 2026. "Lipid Dependence of CYP3A4 Activity in Nanodiscs" Biology 15, no. 2: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020156

APA StyleDenisov, I. G., Grinkova, Y. V., & Sligar, S. G. (2026). Lipid Dependence of CYP3A4 Activity in Nanodiscs. Biology, 15(2), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020156