Adsorption Characterization and Mechanism of a Red Mud–Lactobacillus plantarum Composite Biochar for Cd2+ and Pb2+ Removal

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

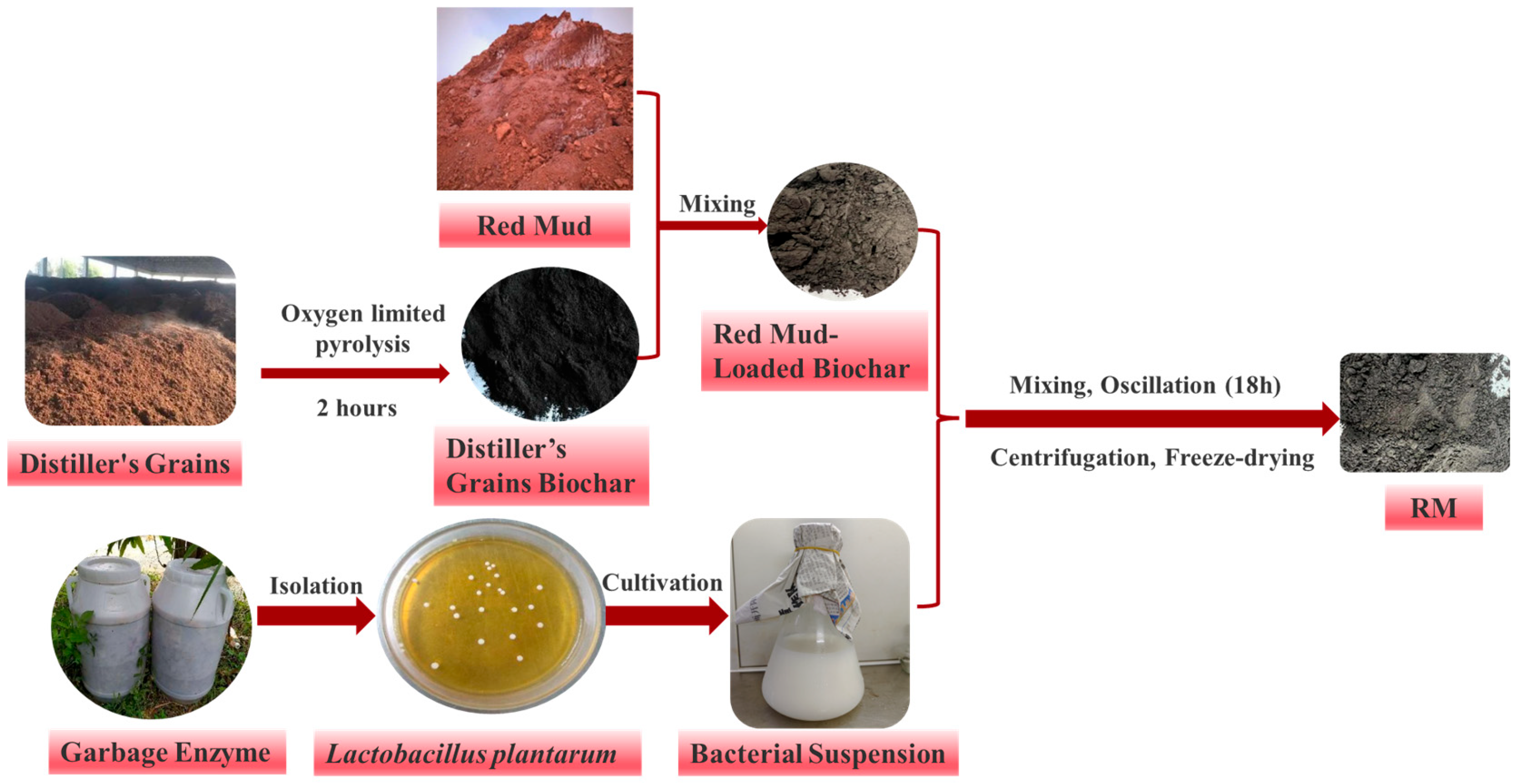

2.1. Biochar Preparation

2.2. Characterization of Biochar

2.3. Adsorption Experiment Design

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Calculation of Adsorption Capacity and Efficiency

2.4.2. Isothermal Adsorption Model

2.4.3. Kinetic Model

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of RM

3.1.1. Physicochemical Properties of BC and RM

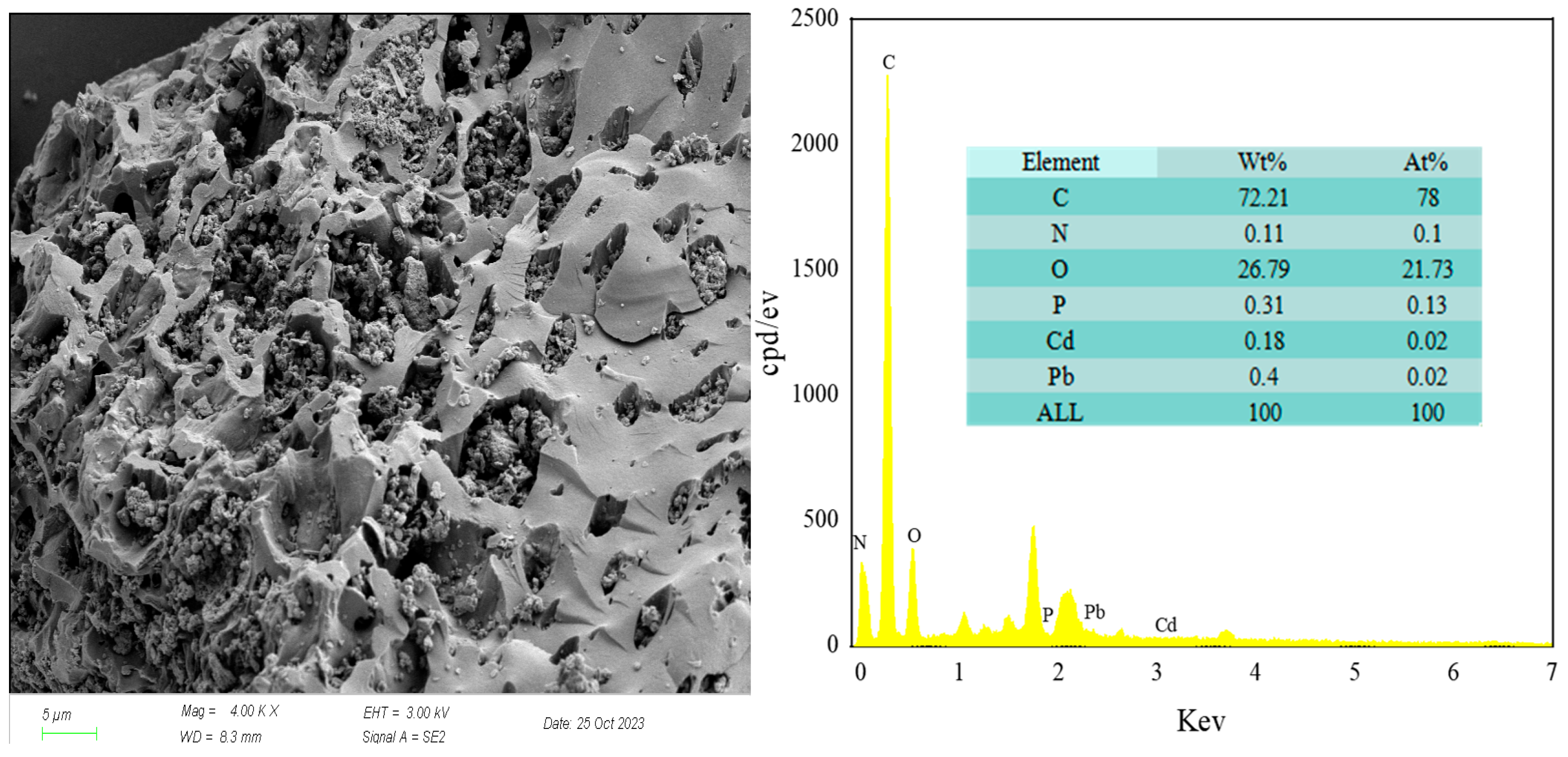

3.1.2. Surface Morphology and Elemental Composition of RM

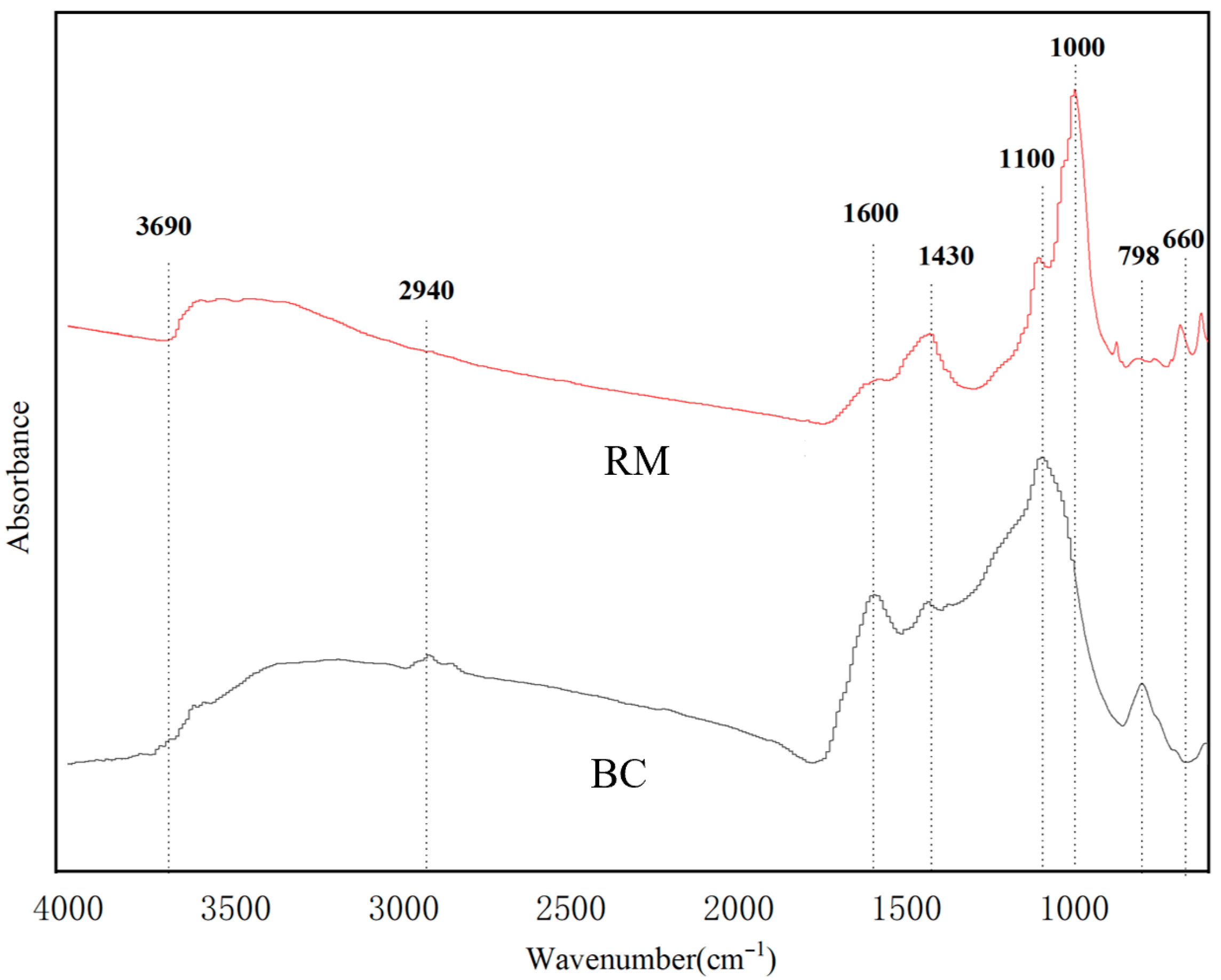

3.1.3. FTIR Analysis of RM

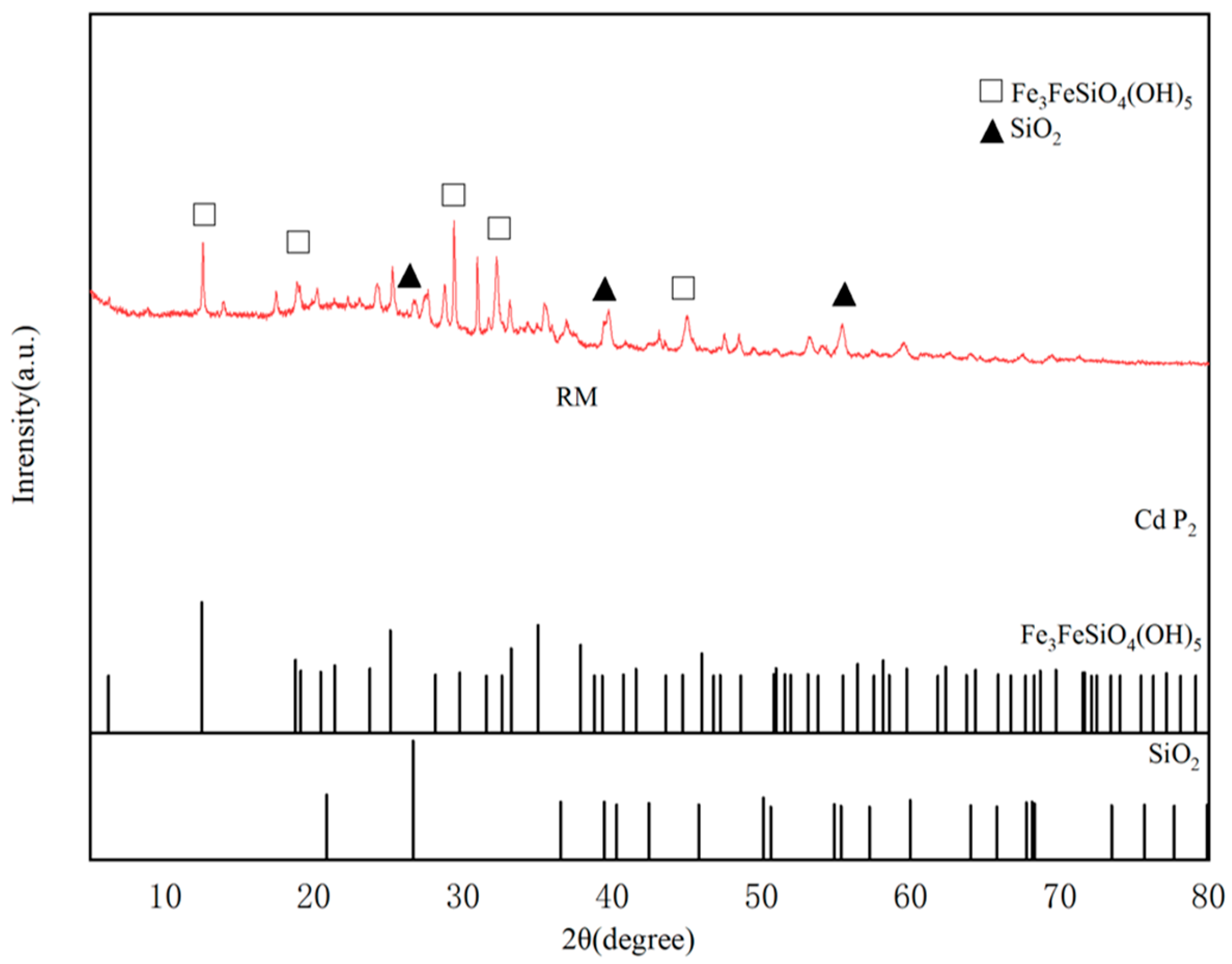

3.1.4. XRD Analysis of RM

3.2. Adsorption Performance of RM for Cd2+ and Pb2+

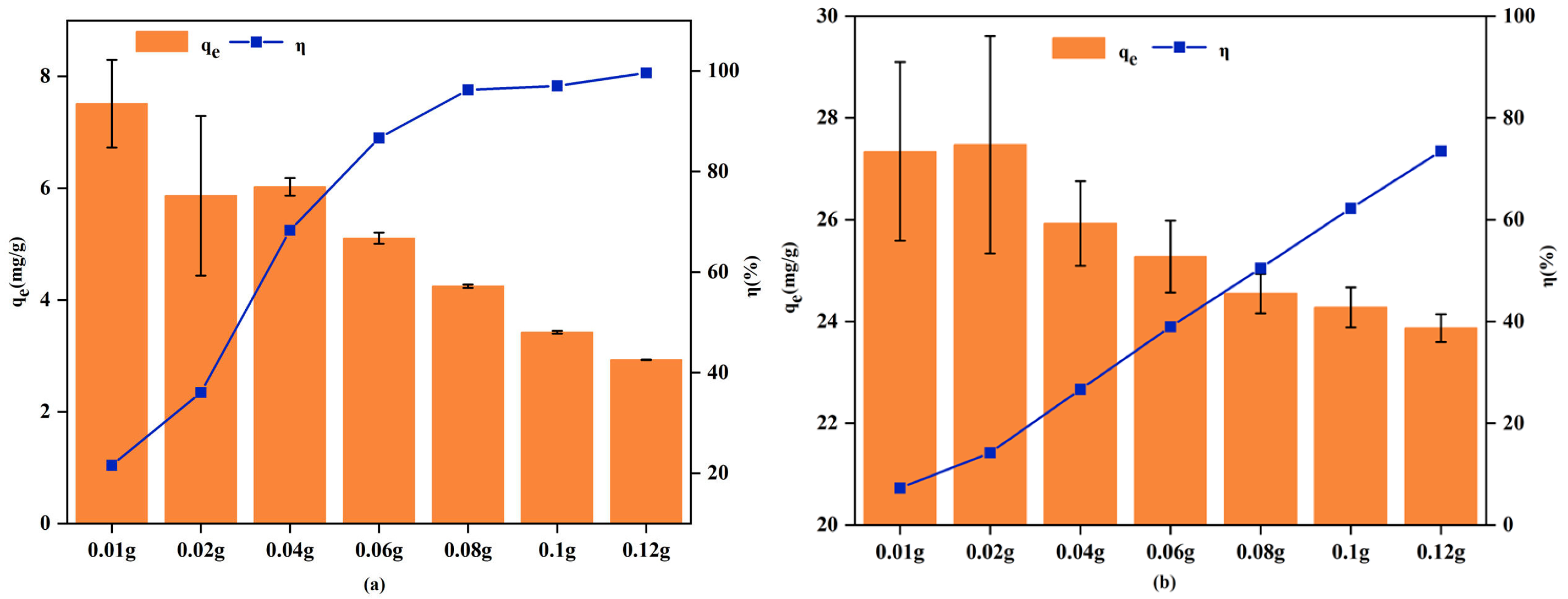

3.2.1. Effect of Adsorbent Dosage

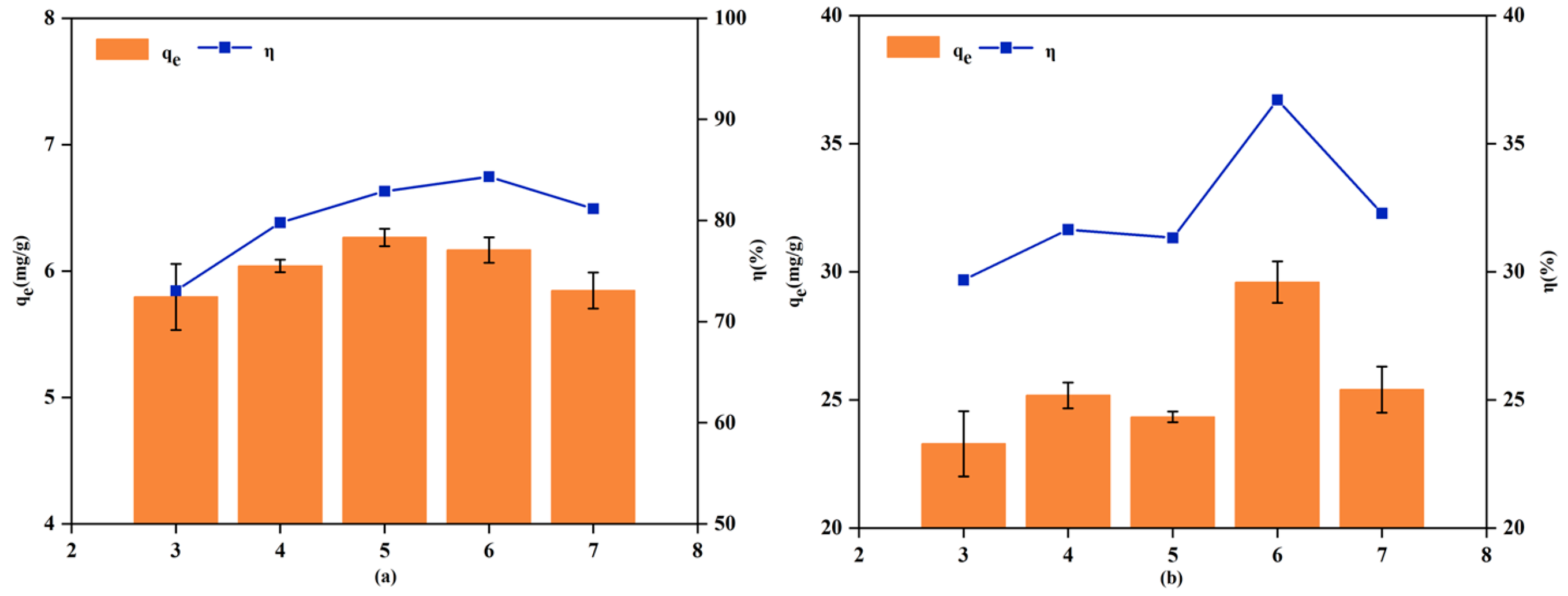

3.2.2. Effect of Solution pH

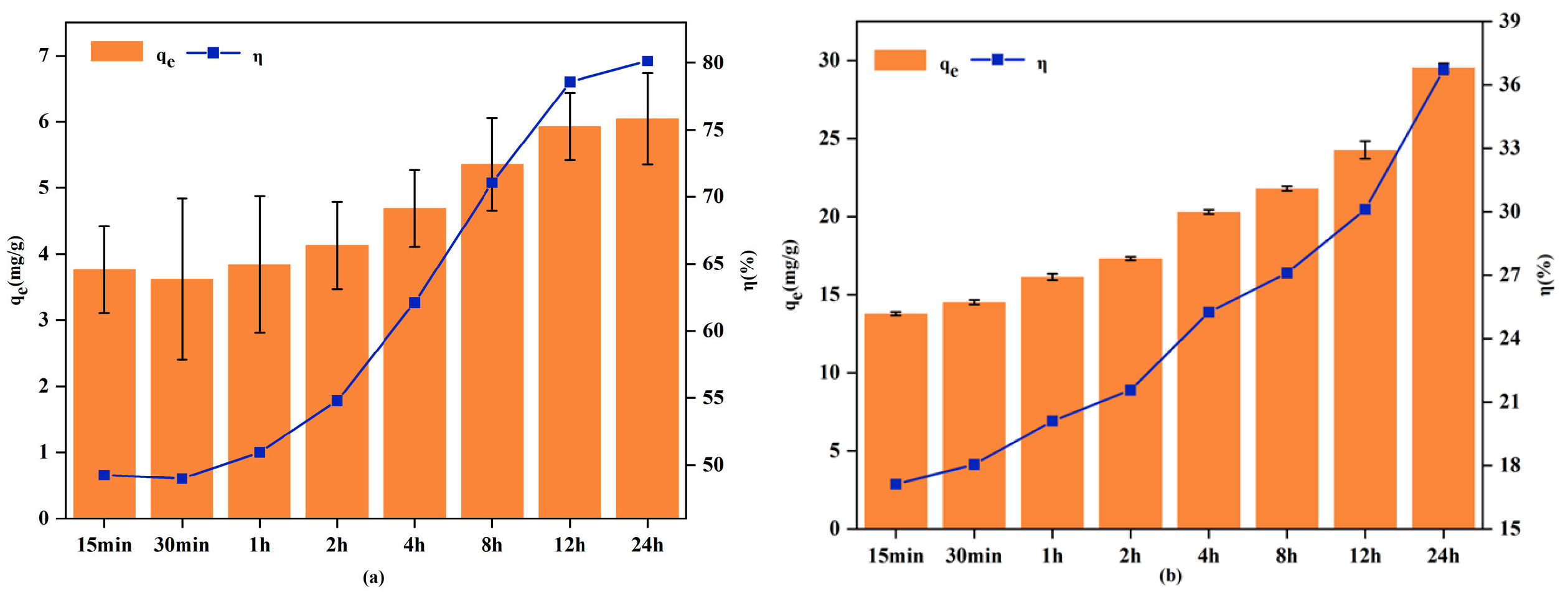

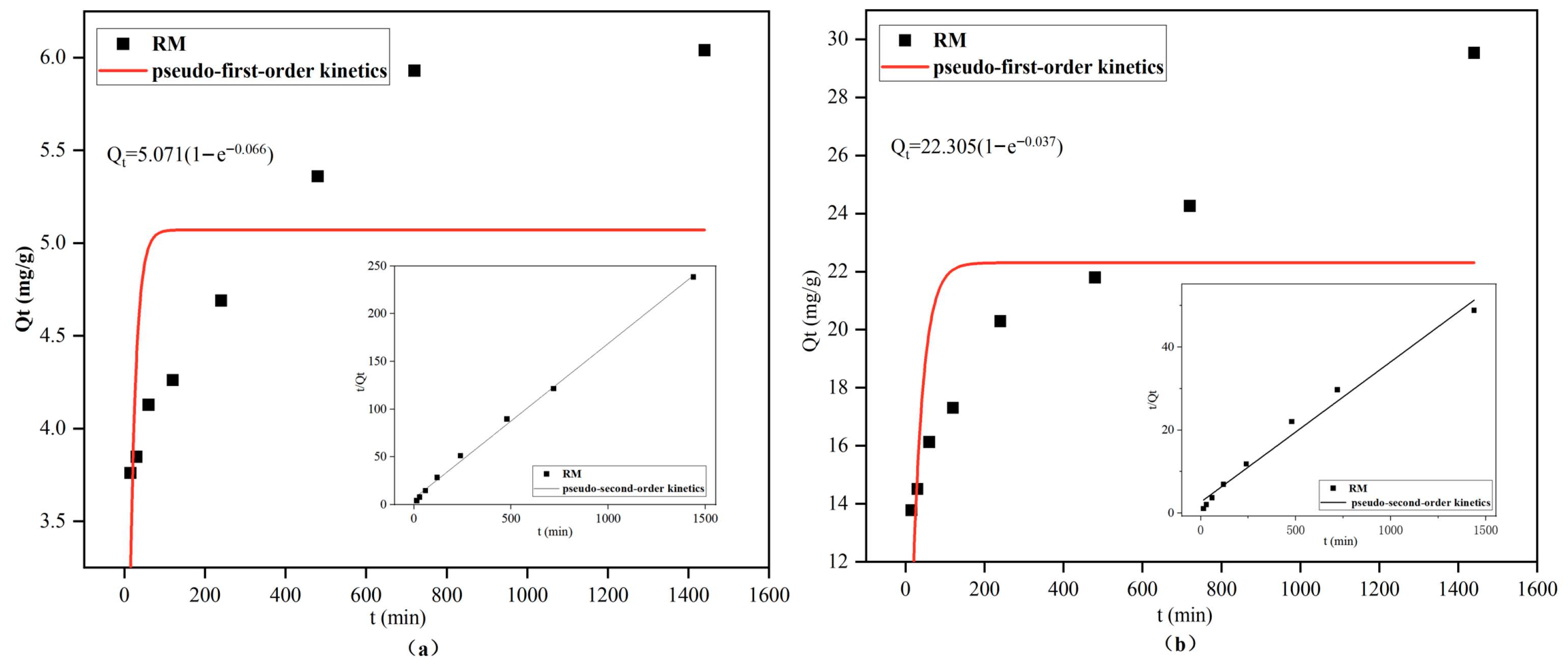

3.2.3. Adsorption Kinetics

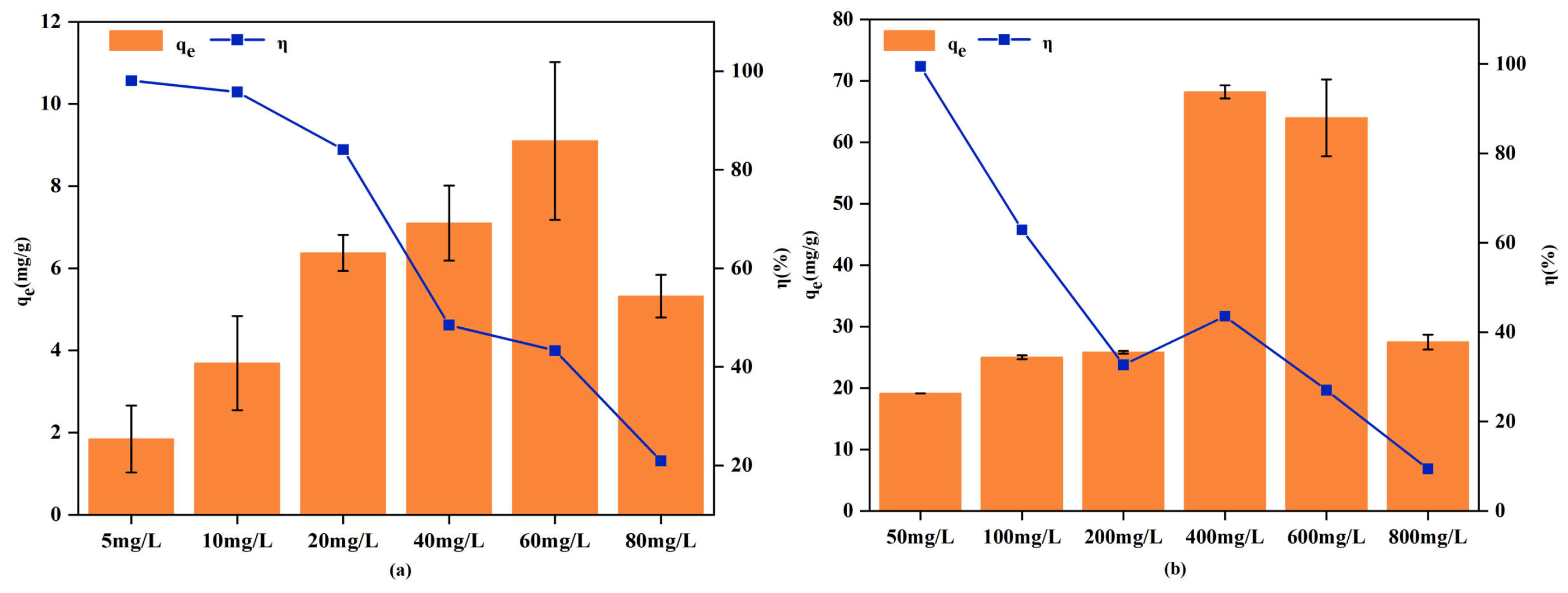

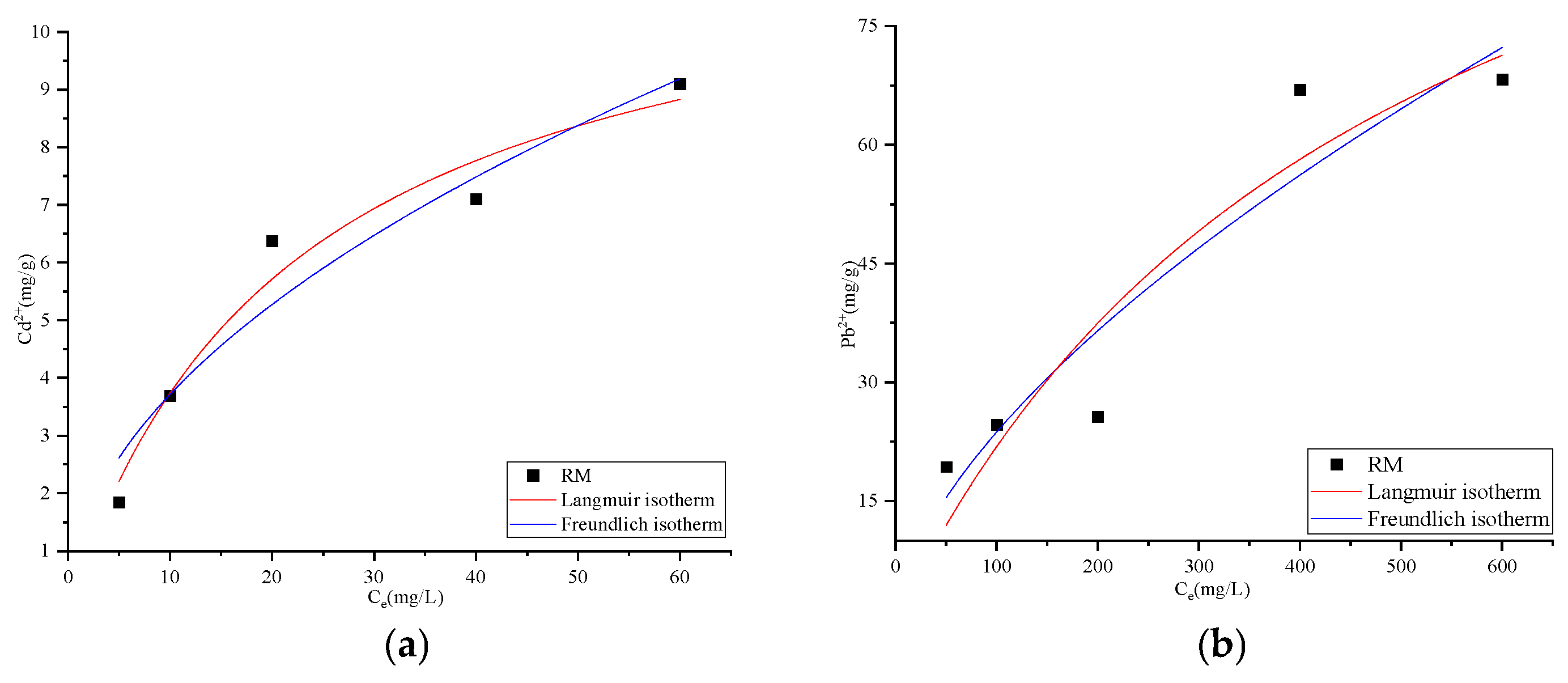

3.2.4. Adsorption Isotherms

3.3. Characterization After Adsorption

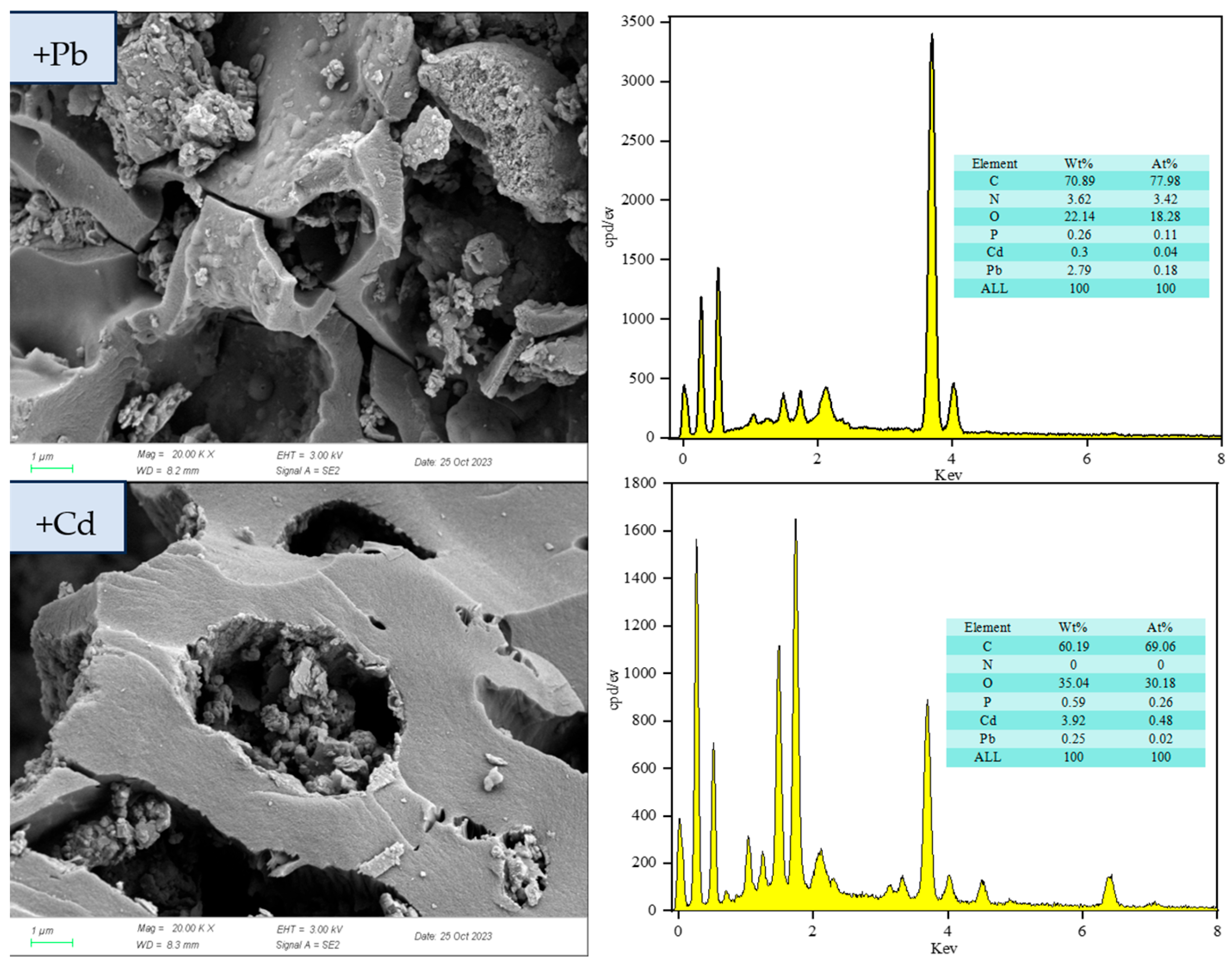

3.3.1. Surface Morphology and Elemental Composition

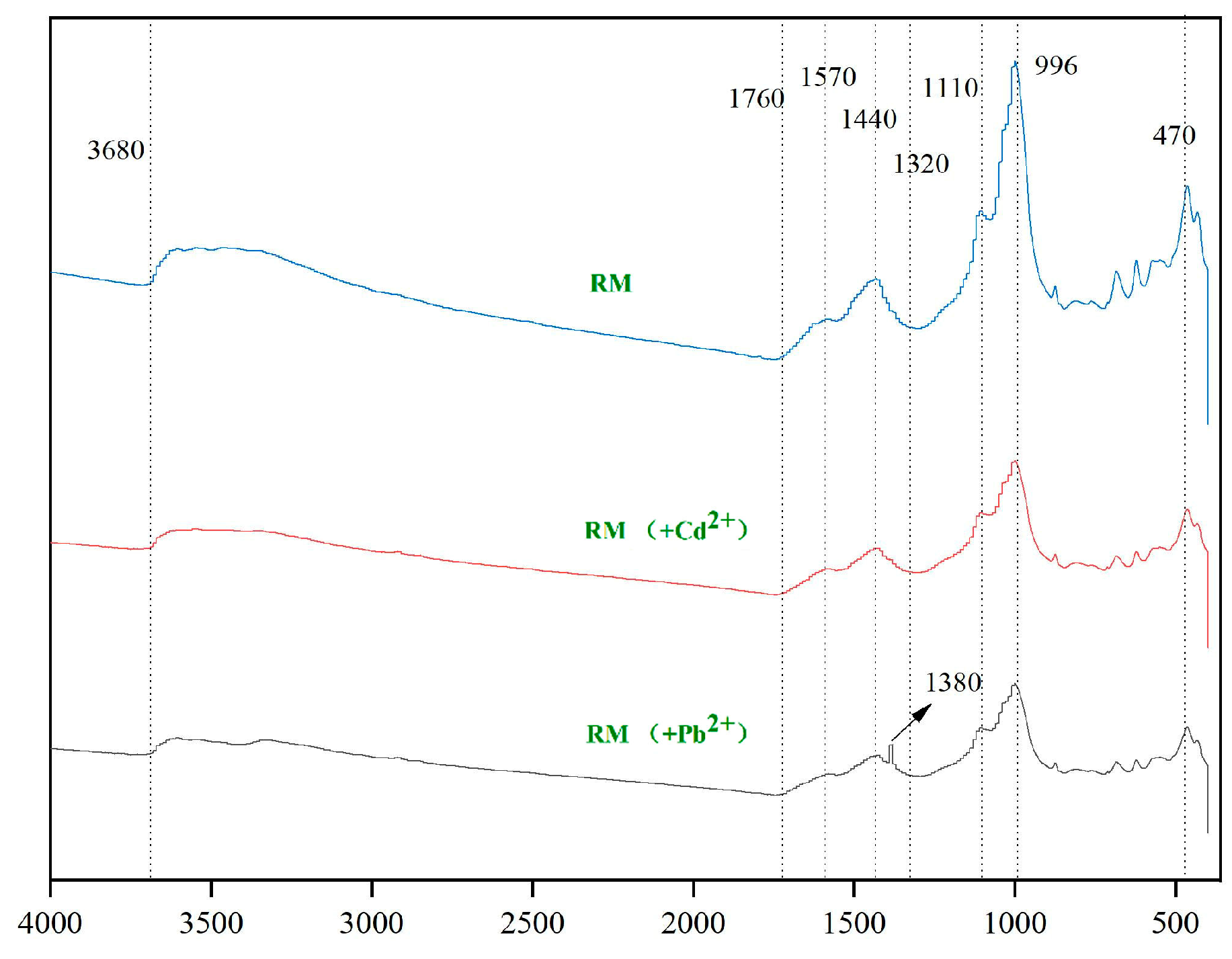

3.3.2. FTIR Analysis

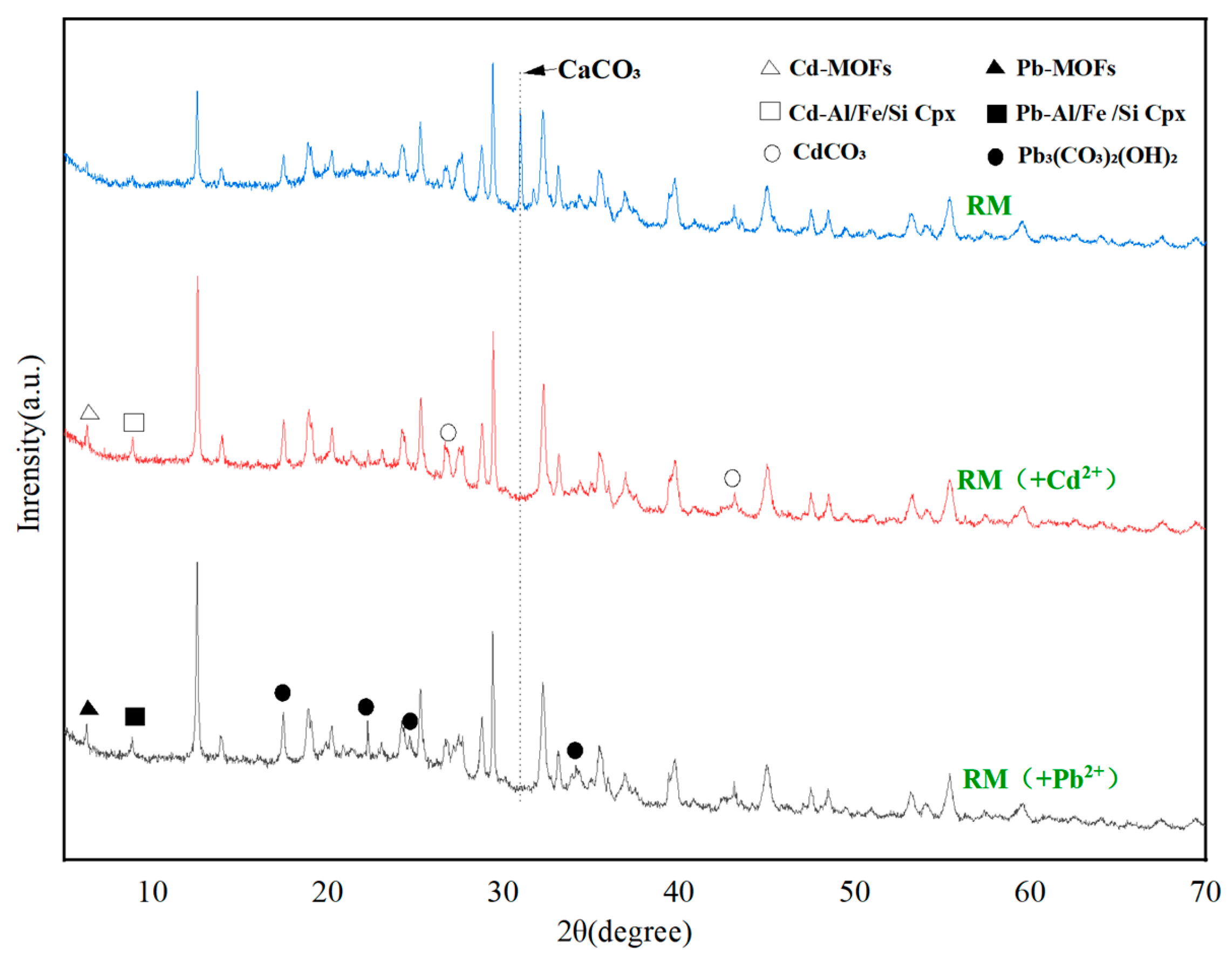

3.3.3. XRD Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanistic Analysis of Cd2+ and Pb2+ Adsorption by RM

4.2. Implications for Application and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- This study innovatively develops a ternary composite biochar (RM) by immobilizing red mud (mineral component), Lactobacillus plantarum (microorganism), and distiller’s grain-derived biochar (porous carrier), filling the research gap of underutilized synergies between three types of components in existing binary composite adsorbents. Compared with binary counterparts (e.g., biochar + Lactobacillus plantarum, biochar + red mud), RM exhibits enhanced adsorption capacities for Cd2+ (12.13 mg/g) and Pb2+ (130.10 mg/g), verifying the superior performance of the ternary integration strategy.

- (2)

- The adsorption of Cd2+ and Pb2+ by RM is governed by synergistic chemical interactions (surface complexation, ion exchange, coprecipitation) with auxiliary textural optimization. Distinct adsorption behaviors (Langmuir monolayer for Cd2+, Freundlich multilayer for Pb2+) arise from the interplay between metal ionic properties and RM’s heterogeneous surface, providing new insights into the design of composite adsorbents for targeted heavy metal removal.

- (3)

- RM demonstrates promising practical potential for heavy metal-contaminated water remediation, supported by feasible end-of-life management strategies (solidification/stabilization, regeneration, resource recovery). This study lays a theoretical and technical foundation for the development of multi-component composite adsorbents and promotes the sustainable application of industrial by-products in environmental remediation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zamora-Ledezma, C.; Negrete-Bolagay, D.; Figueroa, F.; Zamora-Ledezma, E.; Ni, M.; Alexis, F.; Guerrero, V.H. Heavy metal water pollution: A fresh look about hazards, novel and conventional remediation methods. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 22, 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genchi, G.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Lauria, G.; Carocci, A.; Catalano, A. The effects of cadmium toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Zheng, W.W. Cadmium Exposure: Mechanisms and pathways of toxicity and implications for human health. Toxics 2024, 12, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauf, N.; Malik, T. Removal of Pb (II) from aqueous/acidic solutions by using bentonite as an adsorbent. Water Res. 2001, 35, 3982–3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collin, M.S.; Venkatraman, S.K.; Vijayakumar, N.; Kanimozhi, V.; Arbaaz, S.M.; Stacey, R.G.S.; Anusha, J.; Choudhary, R.; Lvov, V.; Tovar, G.I.; et al. Bioaccumulation of lead (Pb) and its effects on human: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 7, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, H.R.; Flannery, B.M.; Crosby, L.; Jones-Dominic, O.E.; Punzalan, C.; Middleton, K. A systematic review of adverse health effects associated with oral cadmium exposure. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 134, 105243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Guo, J. Removal of chromium from wastewater by membrane filtration, chemical precipitation, ion exchange, adsorption electrocoagulation, electrochemical reduction, electrodialysis, electrodeionization, photocatalysis and nano-technology: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 2055–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayach, J.; El Malti, W.; Duma, L.; Lalevée, J.; Al Ajami, M.; Hamad, H.; Hijazi, A. Comparing conventional and advanced approaches for heavy metal removal in waste⁃ water treatment: An in-depth review emphasizing filterbased strategies. Polymers 2024, 16, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Oar, C.; Abdeldayem, O.M.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Rene, E.R. Current updates and perspectives of biosorption technology: An alternative for the removal of heavy metals from wastewater. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2020, 6, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shannag, M.; Al-Qodah, Z.; Bani-Melhem, K.; Qtaishat, M.R.; Alkasrawi, M. Heavy metal ions removal from metal plating wastewater using electrocoagulation: Kinetic study and process performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 260, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.L.; Wang, Q. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewaters: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Priya, A.K.; Kumar, P.S.; Hoang, T.K.A.; Sekar, K.; Chong, K.Y.; Khoo, K.S.; Ng, H.S.; Show, P.L. A critical and recent developments on adsorption technique for removal of heavy metals from wastewater—A review. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 135146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, S.; Dey, S. Review on biochar as an adsorbent material for removal of dyes from waterbodies. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 9335–9350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastav, A.L.; Pham, T.D.; Izah, S.C.; Singh, N.; Singh, P.K. Biochar adsorbents for arsenic removal from water environment: A review. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2022, 108, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Liu, R.; Chen, L.; Wang, Q. Efficient adsorption removal of phosphate from rural domestic sewage by waste eggshell-modified peanut shell biochar adsorbent materials. Materials 2023, 16, 5873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, M.I.; Gao, B.; Yao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Zimmerman, A.; Mosa, A.; Pullammanappallil, P.; Ok, Y.S.; Cao, X. A review of biochar as a low-cost adsorbent for aqueous heavy metal removal. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 46, 406–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Yang, W.; Li, J.; Yao, Z. The application of biochar as heavy metals adsorbent: The preparation, mechanism, and perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2024, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amen, R.; Yaseen, M.; Mukhtar, A.; Klemeš, J.J.; Saqib, S.; Ullah, S.; Al-Sehemi, A.G.; Rafiq, S.; Babar, M.; Fatt, C.L.; et al. Lead and cadmium removal from wastewater using eco-friendly biochar adsorbent derived from rice husk, wheat straw, and corncob. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2020, 1, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.; Tang, J.; Huang, Y.; Gai, L.; Zeng, E.Y.; Liber, K.; Gong, Y. Removal of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solutions by a novel biochar supported nanoscale iron sulfide composite. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 322, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Mehmood, S.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; Ali, S.; Qaswar, M.; Khan, Z.H.; Ying, H.; Chen, D.Y. Utilization of Citrullus lanatus L. seeds to synthesize a novel MnFe2O4-biochar adsorbent for the removal of U (VI) from wastewater: Insights and comparison between modified and raw biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 144955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mao, W.; Yang, W.; Niazi, N.K.; Wang, B.; Wu, P. A novel phosphate rock-magnetic biochar for Pb2+ and Cd2+ removal in wastewater: Characterization, performance and mechanisms. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 32, 103268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Wu, C.; Xue, S.; Chen, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, W. Synergistic multi-metal stabilization of lead–zinc smelting contaminated soil by Ochrobactrum EEELCW01-loaded iron-modified biochar: Performance and long-term efficacy. Biochar 2025, 7, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Li, F.; Li, X.; Rong, X.; Oh, K. Biochar-clay, biochar-microorganism and biochar-enzyme composites for environmental remediation: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1837–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, H.; Xin, C.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, Q.; Cao, C.; Chao, H.; Wu, T.; Zheng, S. Insight into adsorption of Pb (II) with wild resistant bacteria TJ6 immobilized on biochar composite: Roles of bacterial cell and biochar. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 331, 125660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Li, Z.; Xu, X.; Liu, H.; Cao, Y.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Z.; Guo, P.; Qing, Y.; Wu, Y. Hydrangea-like biomimetic MgO-modified coconut shell biochar for remediation of multi-media heavy metal pollution: Morphological innovation and underlying mechanisms. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 500, 140337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Sarkar, B.; Aralappanavar, V.K.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Basak, B.B.; Srivastava, P.; Marchut-Mikołajczyk, O.; Bhatnagar, A.; Semple, K.T.; Bolan, N. Biochar-microorganism interactions for organic pollutant remediation: Challenges and perspectives. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 308, 119609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Wang, X.; Ivshina, I.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Tao, Y.; Qu, J.; Zhang, Y. Biochar-based microbial agents enhance heavy metals passivation and promote plant growth by recruiting beneficial microorganism. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 165929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yuan, P.; Yang, Z.; Peng, W.; Meng, X.; Cheng, J. Integration of micro-nano-engineered hydroxyapatite/biochars with optimized sorption for heavy metals and pharmaceuticals. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babeker, T.M.A.; Khalil, M.N.; Fayad, E.; Alshaya, D.S.; Elsaid, F.G.; Elhassan, I.A. Superior Cu (II) purification using carrageenan biochar-olivine composite: Synergistic effects of K (I), Mg (II), Fe (II/III), and Si (IV). Environ. Res. 2025, 285, 122282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, L.; Yao, B.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, D.; Li, Y.; Zhu, P.; Li, W.; et al. Magnetic activated biochar prepared via a novel iron-loading method for efficient lead adsorption and recyclability. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 119310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, X.; Du, R.; Wen, S.; Du, L.; Tu, Q. Adsorption of Cd2+ by Lactobacillus plantarum immobilized on distiller’s grains biochar: Mechanism and action. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cui, J.; Li, G.; Du, C.; Wen, K. Remediation mechanism of high concentrations of multiple heavy metals in contaminated soil by Sedum alfredii and native microorganisms. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 147, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhakta, J.N.; Ohnishi, K.; Munekage, Y.; Iwasaki, K.; Wei, M.Q. Characterization of lactic acid bacteria-based probiotics as potential heavy metal sorbents. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 112, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halttunen, T.; Salminen, S.; Tahvonen, R. Rapid removal of lead and cadmium from water by specific lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 114, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q.; Wang, H.; Tian, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Dietary Lactobacillus plantarum supplementation decreases tissue lead accumulation and alleviates lead toxicity in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquac. Res. 2017, 48, 5094–5103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Li, Y.; Cheng, D.; Chen, R.; Wang, Y.; Tu, Q. Effects of distiller’s grains biochar and Lactobacillus plantarum on the remediation of Cd-Pb-Zn-contaminated soil and growth of Sorghum-Sudangrass. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D.; Lu, C.; Pang, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G. Adsorption of ammonium nitrogen from aqueous solution on chemically activated biochar prepared from sorghum distillers grain. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, D.; Qian, A.; Jiang, L.; Cai, J.; Huang, L.; Yuan, J.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Zuo, H.; et al. Red mud as the catalyst for energy and environmental catalysis: A review. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 13737–13759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Naidu, R.; Ming, H. Red mud as an amendment for pollutants in solid and liquid phases. Geoderma 2011, 163, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.S.; Reddy, N.G.; Serjun, V.Z.; Mohanty, B.; Das, S.K.; Reddy, K.R.; Rao, B.H. Properties and assessment of applications of red mud (bauxite residue): Current status and research needs. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 1185–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandekar, S.; Korde, S.; Jugade, R.M. Red mud-chitosan microspheres for removal of coexistent anions of environmental significance from water bodies. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santona, L.; Castaldi, P.; Melis, P. Evaluation of the interaction mechanisms between red muds and heavy metals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 136, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, W.; Kim, Y.K. Stabilization of heavy metal contaminated marine sediments with red mud and apatite composite. J. Soils Sediments 2016, 16, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, P.; Silvetti, M.; Santona, L.; Enzo, S.; Melis, P. XRD, FTIR, and thermal analysis of bauxite ore-processing waste (red mud) exchanged with heavy metals. Clays Clay Miner. 2008, 56, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaashikaa, P.R.; Kumar, P.S.; Varjani, S.; Saravanan, A.J.B.R. A critical review on the biochar production techniques, characterization, stability and applications for circular bioeconomy. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 28, e00570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.B.; Dong, Z.M.; Dai, Y.; Xiao, S.; Cao, X.H.; Liu, Y.H.; Guo, W.H.; Luo, M.B.; Le, Z.G. Amidoxime-functionalized hydrothermal carbon materials for uranium removal from aqueous solution. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 102462–102471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Bajwa, B.S.; Kaur, I. (Zn/Co)-zeolitic imidazolate frameworks: Room temperature synthesis and application as promising U(VI) scavengers–A comparative study. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 93, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pütün, A.E.; Özbay, N.; Önal, E.P.; Pütün, E. Fixed-bed pyrolysis of cotton stalk for liquid and solid products. Fuel Process. Technol. 2005, 86, 1207–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Liu, Y.J.; Naidu, R.; Parikh, S.J.; Du, J.H.; Qi, F.J.; Willett, I.R. Influences of feedstock sources and pyrolysis temperature on the properties of biochar and functionality as adsorbents: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 744, 140714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syguła, E.; Ciolkosz, D.; Białowiec, A. The significance of structural components of lignocellulosic biomass on volatile organic compounds presence on biochar-a review. Wood Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 859–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Sun, K.; Huang, C.; Yang, M.; Fan, M.; Wang, A.; Zhang, G.; Li, B.; Jiang, J.; Xu, W.; et al. Investigation on the mechanism of structural reconstruction of biochars derived from lignin and cellulose during graphitization under high temperature. Biochar 2023, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Herbert, S.; Xing, B. Sorption of antibiotic sulfamethoxazole varies with biochars produced at different temperatures. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 181, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, S.; Qiu, R. Relative distribution of Pb2+ sorption mechanisms by sludge-derived biochar. Water Res. 2012, 46, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, T.; Hao, P.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, L. Effect of oxidation-induced aging on the adsorption and co-adsorption of tetracycline and Cu2+ onto biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 673, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Cui, P.; Liu, C.; Sun, Q.; Wu, T.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y. Overlooked impact of amorphous SiO2 in biochar ash on cadmium behavior during the aging of ferrihydrite-biochar-cadmium coprecipitates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 14685–14694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunali, S.; Akar, T.; Özcan, A.S.; Kiran, I.; Özcan, A. Equilibrium and kinetics of biosorption of lead (II) from aqueous solutions by Cephalosporium aphidicola. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2006, 47, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, D.; Laldanwngliana, C.; Choi, C.-H.; Lee, S.M. Manganese-modified natural sand in the remediation of aquatic environment contaminated with heavy metal toxic ions. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 171, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revellame, E.D.; Fortela, D.L.; Sharp, W.; Hernandez, R.; Zappi, M.E. Adsorption kinetic modeling using pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order rate laws: A review. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2020, 1, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodyńska, D.; Krukowska, J.A.; Thomas, P. Comparison of sorption and desorption studies of heavy metal ions from biochar and commercial active carbon. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 307, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komkiene, J.; Baltrenaite, E. Biochar as adsorbent for removal of heavy metal ions [Cadmium (II), Copper (II), Lead (II), Zinc (II)] from aqueous phase. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 13, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banwo, K.; Alonge, Z.; Sanni, A.I. Binding capacities and antioxidant activities of Lactobacillus plantarum and Pichia kudriavzevii against cadmium and lead toxicities. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021, 199, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.K.; Kim, W.H.; Park, J.; Cho, J.; Jeong, T.Y.; Park, P.K. Application of Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms to predict adsorbate removal efficiency or required amount of adsorbent. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 28, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanbakht, V.; Ghoreishi, S.M.; Habibi, N.; Javanbakht, M. A novel magnetic chitosan/clinoptilolite/magnetite nanocomposite for highly efficient removal of Pb (II) ions from aqueous solution. Powder Technol. 2016, 302, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.H.; Hao, X.R.; Deng, Y.R.; Su, J.K.; Yi, X.Y.; Dang, Z. Adsorption of Cd2+ by biochar immobilized cadmium-tolerant bacterial flora and the mechanism of action. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2023, 43, 136–146. [Google Scholar]

- Kalam, S.; Abu-Khamsin, S.A.; Kamal, M.S.; Patil, S. Surfactant adsorption isotherms: A review. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 32342–32348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Chauhan, P.; Kaur, C.; Perveen, S.; Arora, P.K.; Garg, S.K.; Singh, V.P.; Srivastava, A. Bacterial bioremediation strategies for heavy metal detoxification: A multidisciplinary approach. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 8, 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Ye, S.; Wu, H.; Xiao, R.; Zeng, G.; Liang, J.; Zhang, C.; Yu, J.; Fang, Y.; Song, B. Research on the sustainable efficacy of g-MoS2 decorated biochar nanocomposites for removing tetracycline hydrochloride from antibiotic-polluted aqueous solution. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, J.P.; Chen, G.S.; Huang, Y.H.; Sun, A.C.; Chen, C.Y. Ecofriendly heavy metal stabilization: Microbial induced mineral precipitation (MIMP) and biomineralization for heavy metals within the contaminated soil by indigenous bacteria. Geomicrobiol. J. 2019, 36, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.; Olejar, K.J.; Parpinello, G.P.; Kilmartin, P.A.; Versari, A. Application of Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy in the characterization of tannins. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2015, 50, 407–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achour, A.; Arman, A.; Islam, M.; Zavarian, A.A.; Al-Zubaidi, B.A.; Szade, J. Synthesis and characterization of porous CaCO3 micro/nano-particles. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2017, 132, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, L.T.; Dang, H.T.; Tran, H.V.; Hoang, G.T.; Huynh, C.D. MIL-88B(Fe)-NH2: An amine-functionalized metal–organic framework for application in a sensitive electrochemical sensor for Cd2+, Pb2+, and Cu2+ ion detection. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 21861–21872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.Y.; Kang, S.H.; Hwang, K.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.G.; Song, H.; Hwang, I. Evaluation of phosphate fertilizers and red mud in reducing plant availability of Cd, Pb, and Zn in mine tailings. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 2659–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Qiao, C. Magnetic chitosan-modified apple branch biochar for cadmium removal from acidic solution. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2025, 15, 16229–16242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cunha, D.L.; Pereira, G.F.C.; Felix, J.F.; Aguiar, J.A.; De Azevedo, W.M. Nanostructured hydrocerussite compound (Pb3(CO3)2(OH)2) prepared by laser ablation technique in liquid environment. Mater. Res. Bull. 2014, 49, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L. Adsorption of Pb2+ and Zn2+ by Red Mud Modified Grains Biochar and Its Application. Master’s Thesis, Guizhou Minzu University, Guiyang, China, 2023. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Experimental Projects | Variable Settings | Fixed Condition |

|---|---|---|

| One-way experiment | Dosage of RM: 0.01 g–0.12 g | [Cd2+] = 20 mg/L, [Pb2+] = 200 mg/L, pH = 6.0, Contact time = 1440 min |

| pH: 3.0–7.0 | [Cd2+] = 20 mg/L, [Pb2+] = 200 mg/L, Dosage of RM = 50 mg, Contact time = 1440 min | |

| Kinetic experiment | Contact time: 15–1440 min | [Cd2+] = 20 mg/L, [Pb2+] = 200 mg/L, pH = 6.0, Dosage = 50 mg |

| Isothermal adsorption experiment | [Cd2+]: 5–80 mg/L, [Pb2+]: 50–800 mg/L | pH = 6.0, Dosage of RM = 50 mg, Contact time = 1440 min |

| Biochar | pH | Yield (%) | Specific Area (m2/g) | Total Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Average Pore Diameter (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC | 9.94 | 63.68 | 5.3207 | 0.0210 | 15.8109 |

| RM | 8.12 | 87.26 | 8.7773 | 0.0293 | 13.7793 |

| Ion | Pseudo-First-Order Kinetic | Pseudo-Second-Order Kinetic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | qe (mg/g) | R2 | K2 | qe (mg/g) | R2 | |

| Cd2+ | 5.0713 | 0.0661 | 0.2271 | 0.0041 | 6.1576 | 0.9971 |

| Pb2+ | 22.305 | 0.0374 | 0.3361 | 0.0004 | 29.6209 | 0.9806 |

| Ion | Langmuir Equation | Freundlich Equation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qm | KL | R2 | KF | 1/n | R2 | |

| Cd2+ | 12.13 | 0.0446 | 0.9557 | 1.1615 | 0.5051 | 0.9203 |

| Pb2+ | 130.10 | 0.0020 | 0.8390 | 1.3540 | 0.6218 | 0.8511 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhu, G.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, B.; Chen, R.; Zhao, X.; Wu, P.; Tu, Q. Adsorption Characterization and Mechanism of a Red Mud–Lactobacillus plantarum Composite Biochar for Cd2+ and Pb2+ Removal. Biology 2026, 15, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020153

Zhu G, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Huang B, Chen R, Zhao X, Wu P, Tu Q. Adsorption Characterization and Mechanism of a Red Mud–Lactobacillus plantarum Composite Biochar for Cd2+ and Pb2+ Removal. Biology. 2026; 15(2):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020153

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Guangxu, Yunhe Zhao, Yunyan Wang, Baohang Huang, Rongkun Chen, Xingyun Zhao, Panpan Wu, and Qiang Tu. 2026. "Adsorption Characterization and Mechanism of a Red Mud–Lactobacillus plantarum Composite Biochar for Cd2+ and Pb2+ Removal" Biology 15, no. 2: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020153

APA StyleZhu, G., Zhao, Y., Wang, Y., Huang, B., Chen, R., Zhao, X., Wu, P., & Tu, Q. (2026). Adsorption Characterization and Mechanism of a Red Mud–Lactobacillus plantarum Composite Biochar for Cd2+ and Pb2+ Removal. Biology, 15(2), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020153