Three Cases Revealing Remarkable Genetic Similarity Between Vent-Endemic Rimicaris Shrimps Across Distant Geographic Regions

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval

2.2. Vent Sampling and Identification

2.3. DNA Extraction, Partial Gene and Mitogenome Sequencing, and Sequence Data Preprocessing

2.4. Tree Construction, Nucleotide Divergence, Haplotype Network, and Gene Flow

2.5. Mitogenome Sequence Comparison

3. Results

3.1. Datasets Prepared from Multi-Gene Sequences

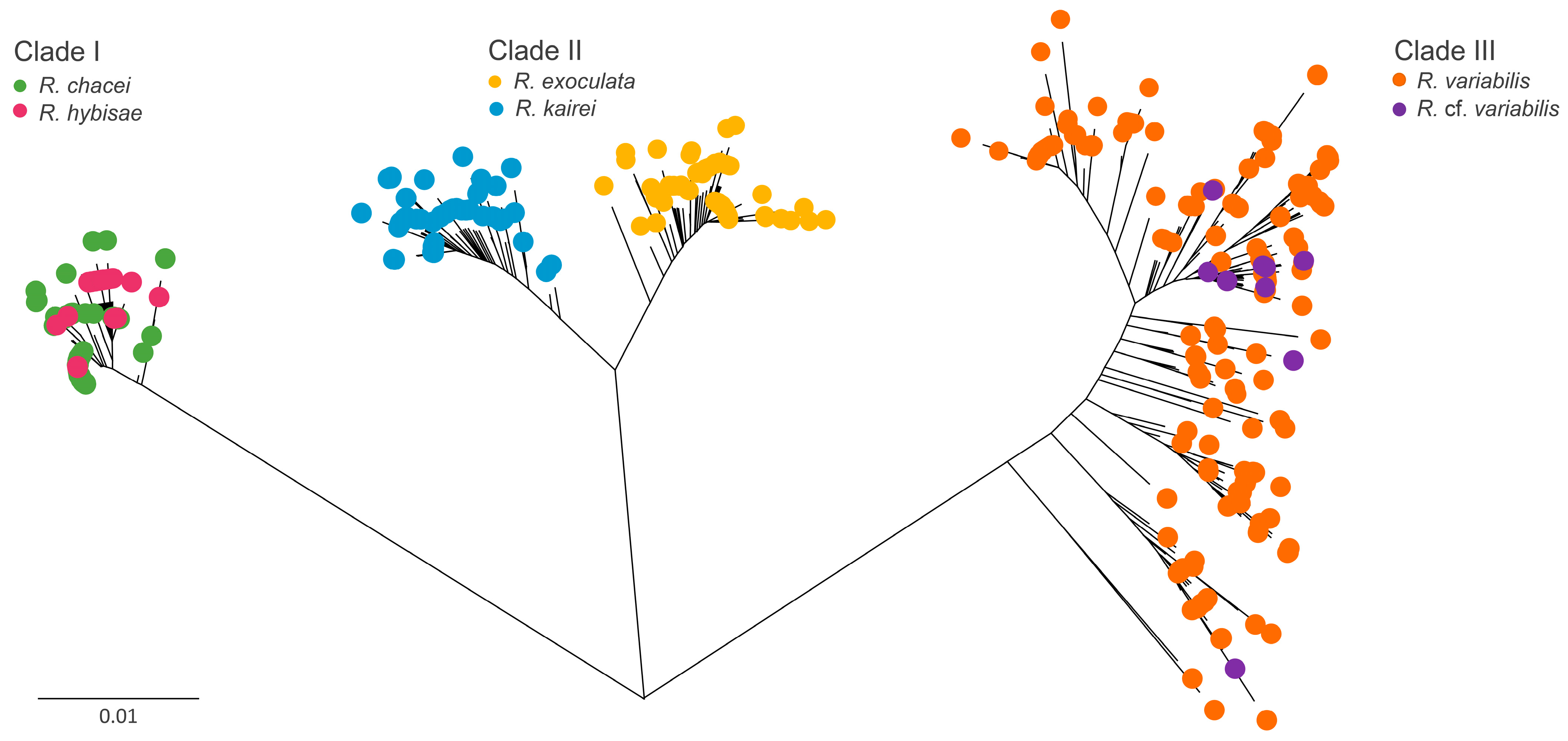

3.2. Genetic Clusters of Rimicaris Species

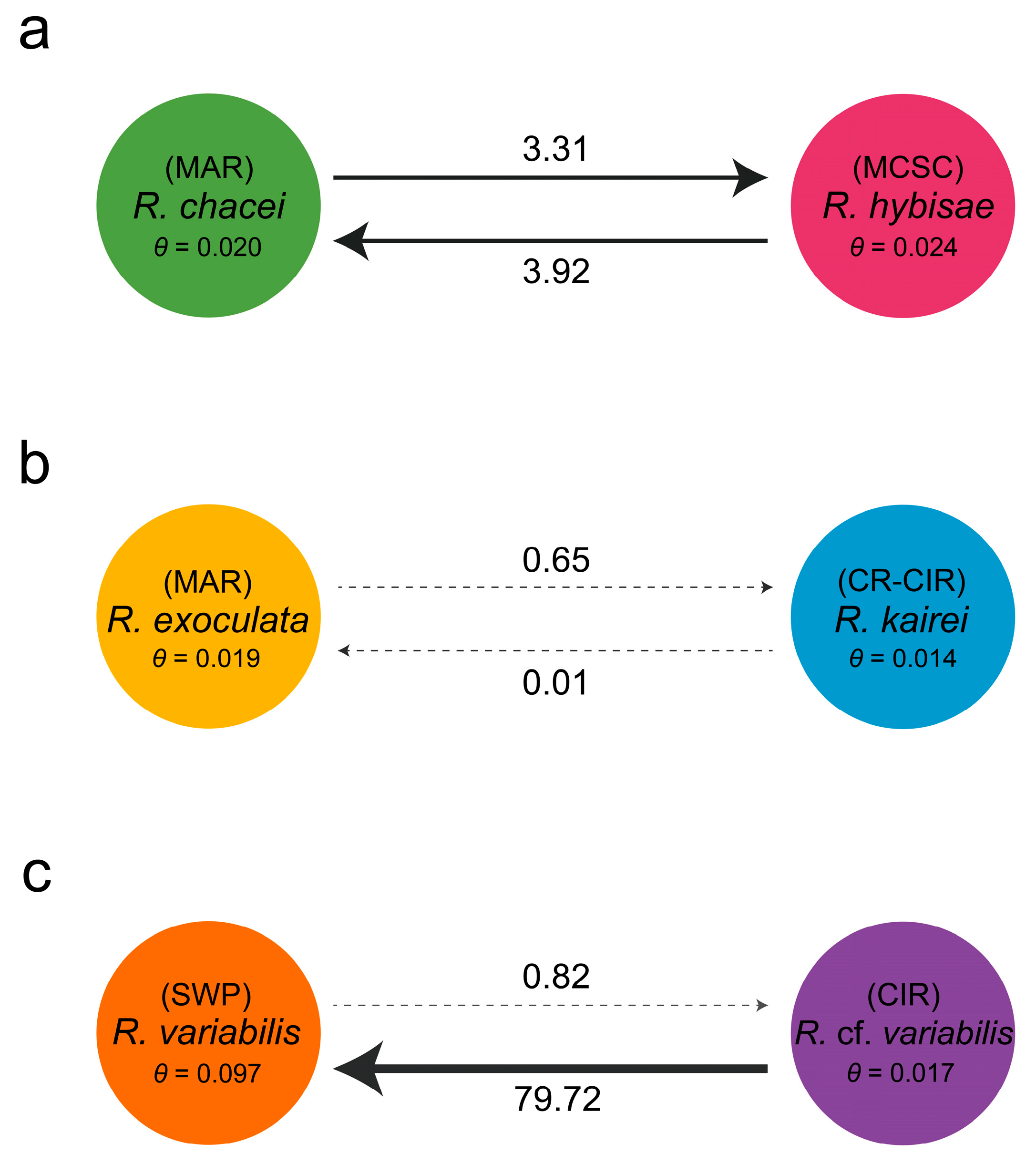

3.3. Genetic Connectivity Between Paired Rimicaris Species Within Each Clade

3.4. Mitogenomic Similarity Between Paired Rimicaris Species

4. Discussion

4.1. Clade-Specific Patterns of Genetic Similarity in Rimicaris

4.2. Adaptive Divergence, Eastward Dispersal, and Regional Barriers in Clade III

| Species (DTE †) | Distribution | Density ‡ | Cephalothorax | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume | Symbiotic Diet | Symbiont § | |||||

| Clade I | R. chacei (n/a) | MAR | Low | Non-enlarged | Partially dependent | C > G | [31,34] |

| R. hybisae (n/a) | MCSC | High or low | Enlarged | Dependent | C | [30,34,74] | |

| Clade II | R. exoculata (≈5 Mya) | MAR | High | Enlarged | Dependent | C > G | [34,75,76,77] |

| R. kairei (≈5 Mya) | CR-CIR | High | Enlarged | Dependent | C > D > B | [66,78,79] | |

| Clade III | R. variabilis (<5 Mya) | SWP | High or low | Non-enlarged | Partially dependent | G > C | [32,33,42,73] |

| R. cf. variabilis (<5 Mya) | CIR | Low | Non-enlarged | Dependent | Not available | [80] This study | |

4.3. Evolutionary Framework of Rimicaris

4.4. New Perspectives on Vent Organism Conservation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramirez-Llodra, E.; Shank, T.M.; German, C.R. Biodiversity and biogeography of hydrothermal vent species: Thirty years of discovery and investigations. Oceanography 2007, 20, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrijenhoek, R.C. Genetic diversity and connectivity of deep-sea hydrothermal vent metapopulations. Mol. Ecol. 2010, 19, 4391–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogin, E.M.; Kleiner, M.; Borowski, C.; Gruber-Vodicka, H.R.; Dubilier, N. Life in the dark: Phylogenetic and physiological diversity of chemosynthetic symbioses. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 75, 695–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, A.; Tunnicliffe, V. Relics and antiquity revisited in the modern vent fauna. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1998, 148, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dover, C.L.; German, C.; Speer, K.G.; Parson, L.; Vrijenhoek, R. Evolution and biogeography of deep-sea vent and seep invertebrates. Science 2002, 295, 1253–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.R.; Takai, K.; Le Bris, N. Hydrothermal vent ecosystems. Oceanography 2007, 20, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moalic, Y.; Desbruyères, D.; Duarte, C.M.; Rozenfeld, A.F.; Bachraty, C.; Arnaud-Haond, S. Biogeography revisited with network theory: Retracing the history of hydrothermal vent communities. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunnicliffe, V.; Chen, C.; Giguère, T.; Rowden, A.A.; Watanabe, H.K.; Brunner, O. Hydrothermal vent fauna of the western Pacific Ocean: Distribution patterns and biogeographic networks. Divers. Distrib. 2024, 30, e13794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, Y.-J.; Hallam, S.J.; O’Mullan, G.D.; Pan, I.L.; Buck, K.R.; Vrijenhoek, R.C. Environmental acquisition of thiotrophic endosymbionts by deep-sea mussels of the genus Bathymodiolus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 6785–6792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanaugh, C.M.; McKiness, Z.P.; Newton, I.L.; Stewart, F.J. Marine chemosynthetic symbioses. Prokaryotes 2006, 1, 475–507. [Google Scholar]

- Dubilier, N.; Bergin, C.; Lott, C. Symbiotic diversity in marine animals: The art of harnessing chemosynthesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullineaux, L.S.; Metaxas, A.; Beaulieu, S.E.; Bright, M.; Gollner, S.; Grupe, B.M.; Herrera, S.; Kellner, J.B.; Levin, L.A.; Mitarai, S.; et al. Exploring the ecology of deep-sea hydrothermal vents in a metacommunity framework. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breusing, C.; Genetti, M.; Russell, S.L.; Corbett-Detig, R.B.; Beinart, R.A. Horizontal transmission enables flexible associations with locally adapted symbiont strains in deep-sea hydrothermal vent symbioses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2115608119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breusing, C.; Xiao, Y.; Russell, S.L.; Corbett-Detig, R.B.; Li, S.; Sun, J.; Chen, C.; Lan, Y.; Qian, P.-Y.; Beinart, R.A. Ecological differences among hydrothermal vent symbioses may drive contrasting patterns of symbiont population differentiation. Msystems 2023, 8, e00284-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- German, C.R.; Petersen, S.; Hannington, M.D. Hydrothermal exploration of mid-ocean ridges: Where might the largest sulfide deposits be forming? Chem. Geol. 2016, 420, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dover, C.L.; Arnaud-Haond, S.; Gianni, M.; Helmreich, S.; Huber, J.A.; Jaeckel, A.L.; Metaxas, A.; Pendleton, L.H.; Petersen, S.; Ramirez-Llodra, E.; et al. Scientific rationale and international obligations for protection of active hydrothermal vent ecosystems from deep-sea mining. Mar. Policy 2018, 90, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, S.; Hannington, M.D.; Petersen, S. Divining gold in seafloor polymetallic massive sulfide systems. Miner. Depos. 2019, 54, 789–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dover, C.L. Impacts of anthropogenic disturbances at deep-sea hydrothermal vent ecosystems: A review. Mar. Environ. Res. 2014, 102, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullineaux, L.; Mills, S.; Le Bris, N.; Beaulieu, S.; Sievert, S.; Dykman, L. Prolonged recovery time after eruptive disturbance of a deep-sea hydrothermal vent community. Proc. R. Soc. B 2020, 287, 20202070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Most, N.; Qian, P.-Y.; Gao, Y.; Gollner, S. Active hydrothermal vent ecosystems in the Indian Ocean are in need of protection. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 9, 1067912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, V.; Copley, J.; Plouviez, S. A new species of Rimicaris (Crustacea: Decapoda: Caridea: Alvinocarididae) from hydrothermal vent fields on the Mid-Cayman spreading centre, Caribbean. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2012, 92, 1057–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereshchaka, A.L.; Kulagin, D.N.; Lunina, A.A. Phylogeny and new classification of hydrothermal vent and seep shrimps of the family Alvinocarididae (Decapoda). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methou, P.; Chen, C.; Komai, T. Revision of the alvinocaridid shrimp genus Rimicaris Williams & Rona, 1986 (Decapoda: Caridea) with description of a new species from the Mariana Arc hydrothermal vents. Zootaxa 2024, 5406, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, S.; Olu, K.; Decker, C.; Cunha, R.L.; Fuchs, S.; Hourdez, S.; Serrão, E.A.; Arnaud-Haond, S. High connectivity across the fragmented chemosynthetic ecosystems of the deep Atlantic Equatorial Belt: Efficient dispersal mechanisms or questionable endemism? Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 4663–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, Z.; Wang, Y. Phylogenetic position of Alvinocarididae (Crustacea: Decapoda: Caridea): New insights into the origin and evolutionary history of the hydrothermal vent alvinocarid shrimps. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2018, 141, 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Q.; Xu, T.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Lin, Y.; Yahagi, T.; Perez, M.; Qian, P.; Qiu, J. Comparative Population Genetics of Two Alvinocaridid Shrimp Species in Chemosynthetic Ecosystems of the Western Pacific. Integr. Zool. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komai, T.; Segonzac, M. A revision of the genus Alvinocaris Williams and Chace (Crustacea: Decapoda: Caridea: Alvinocarididae), with descriptions of a new genus and a new species of Alvinocaris. J. Nat. Hist. 2005, 39, 1111–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.W.; Haney, T.A. Decapod crustaceans from hydrothermal vents and cold seeps: A review through 2005. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2005, 145, 445–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahyong, S.; Boyko, C.B.; Bernot, J.; Brandão, S.N.; Daly, M.; De Grave, S.; de Voogd, N.J.; Gofas, S.; Hernandez, F.; Mees, J.; et al. WoRMS Editorial Board. 2025. Available online: https://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=106779 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Assié, A. Deep se (a) Quencing: A Study of Deep-Sea Ectosymbioses Using Next Generation Sequencing. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Apremont, V.; Cambon-Bonavita, M.-A.; Cueff-Gauchard, V.; François, D.; Pradillon, F.; Corbari, L.; Zbinden, M. Gill chamber and gut microbial communities of the hydrothermal shrimp Rimicaris chacei Williams and Rona 1986: A possible symbiosis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.K.; Juniper, S.K.; Perez, M.; Ju, S.J.; Kim, S.J. Diversity and characterization of bacterial communities of five co-occurring species at a hydrothermal vent on the Tonga Arc. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 4481–4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methou, P.; Cueff-Gauchard, V.; Michel, L.N.; Gayet, N.; Pradillon, F.; Cambon-Bonavita, M.A. Symbioses of alvinocaridid shrimps from the South West Pacific: No chemosymbiotic diets but conserved gut microbiomes. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2023, 15, 614–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methou, P.; Guéganton, M.; Copley, J.T.; Kayama Watanabe, H.; Pradillon, F.; Cambon-Bonavita, M.-A.; Chen, C. Distinct development trajectories and symbiosis modes in vent shrimps. Evolution 2024, 78, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P.D.; Cywinska, A.; Ball, S.L.; DeWaard, J.R. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzen da Silva, J.; Creer, S.; Dos Santos, A.; Costa, A.C.; Cunha, M.R.; Costa, F.O.; Carvalho, G.R. Systematic and evolutionary insights derived from mtDNA COI barcode diversity in the Decapoda (Crustacea: Malacostraca). PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, T.; Coffroth, M. DNA BARCODING: Barcoding corals: Limited by interspecific divergence, not intraspecific variation. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2008, 8, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranasinghe, U.G.S.L.; Eberle, J.; Thormann, J.; Bohacz, C.; Benjamin, S.P.; Ahrens, D. Multiple species delimitation approaches with COI barcodes poorly fit each other and morphospecies—An integrative taxonomy case of Sri Lankan Sericini chafers (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e8942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinsinger, D.; Debruyne, R.; Thomas, M.; Denys, G.L.; Mennesson, M.I.; Utage, J.; Dettai, A. Fishing for barcodes in the Torrent: From COI to complete mitogenomes on NGS platforms. DNA Barcodes 2015, 3, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, A.T.D.A.; Ludwig, S.; Pimentel, J.D.S.M.; de Abreu, N.L.; Nunez-Rodriguez, D.L.; Leal, H.G.; Kalapothakis, E. Use of complete mitochondrial genome sequences to identify barcoding markers for groups with low genetic distance. Mitochondrial DNA Part A 2020, 31, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nymoen, A.R.; Kongsrud, J.A.; Willassen, E.; Bakken, T. When standard DNA barcodes do not work for species identification: Intermixed mitochondrial haplotypes in the Jaera albifrons complex (Crustacea: Isopoda). Mar. Biodivers. 2024, 54, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komai, T.; Tsuchida, S. New records of Alvinocarididae (Crustacea: Decapoda: Caridea) from the southwestern Pacific hydrothermal vents, with descriptions of one new genus and three new species. J. Nat. Hist. 2015, 49, 1789–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Palumbi, S.; Martin, A.; Romano, S.; McMillan, W.; Stice, L.; Grabowski, G. The Simple Fool’s Guide to PCR, version 2.0; University of Honolulu: Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, 1991; Volume 45, pp. 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Colgan, D.J.; McLauchlan, A.; Wilson, G.D.; Livingston, S.; Edgecombe, G.; Macaranas, J.; Cassis, G.; Gray, M. Histone H3 and U2 snRNA DNA sequences and arthropod molecular evolution. Aust. J. Zool. 1998, 46, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierckxsens, N.; Mardulyn, P.; Smits, G. NOVOPlasty: De novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, e18. [Google Scholar]

- Bernt, M.; Donath, A.; Jühling, F.; Externbrink, F.; Florentz, C.; Fritzsch, G.; Pütz, J.; Middendorf, M.; Stadler, P.F. MITOS: Improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2013, 69, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GENALEX 6: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2006, 6, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Librado, P.; Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Lischer, H.E. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: A new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2010, 10, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, A.R.; Crandall, K.A.; Sing, C.F. A cladistic analysis of phenotypic associations with haplotypes inferred from restriction endonuclease mapping and DNA sequence data. III. Cladogram estimation. Genetics 1992, 132, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vences, M.; Patmanidis, S.; Schmidt, J.-C.; Matschiner, M.; Miralles, A.L.; Renner, S.S. Hapsolutely: A user-friendly tool integrating haplotype phasing, network construction, and haploweb calculation. Bioinform. Adv. 2024, 4, vbae083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, P. Comparison of Bayesian and maximum-likelihood inference of population genetic parameters. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beerli, P.; Mashayekhi, S.; Sadeghi, M.; Khodaei, M.; Shaw, K. Population genetic inference with MIGRATE. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2019, 68, e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. KaKs_Calculator 3.0: Calculating selective pressure on coding and non-coding sequences. Genomics Proteom. Bioinform. 2022, 20, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breusing, C.; Johnson, S.B.; Tunnicliffe, V.; Vrijenhoek, R.C. Population structure and connectivity in Indo-Pacific deep-sea mussels of the Bathymodiolus septemdierum complex. Conserv. Genet. 2015, 16, 1415–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.H.; Husemann, M.; Wu, H.H.; Dong, J.; Zhou, C.J.; Wang, X.F.; Gao, Y.N.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, G.R.; Nie, G.X. Phylogeography of Bellamya (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Viviparidae) snails on different continents: Contrasting patterns of diversification in China and East Africa. BMC Evol. Biol. 2019, 19, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenaka, M.; Yano, K.; Tojo, K. Phylogeography of the true freshwater crab, Geothelphusa dehaani: Detected dual dispersal routes via land and sea. Zoology 2023, 160, 126118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P.D.; Ratnasingham, S.; De Waard, J.R. Barcoding animal life: Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 divergences among closely related species. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, S96–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, P. How to use MIGRATE or why are Markov chain Monte Carlo programs difficult to use. Popul. Genet. Anim. Conserv. 2009, 17, 42–79. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, D.P.; Copley, J.T.; Murton, B.J.; Stansfield, K.; Tyler, P.A.; German, C.R.; Van Dover, C.L.; Amon, D.; Furlong, M.; Grindlay, N.; et al. Hydrothermal vent fields and chemosynthetic biota on the world’s deepest seafloor spreading centre. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yearsley, J.; Salmanidou, D.; Carlsson, J.; Burns, D.; Van Dover, C. Biophysical models of persistent connectivity and barriers on the northern Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2020, 180, 104819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, D.E. Song variation in an avian ring species. Evolution 2000, 54, 998–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, D.E.; Bensch, S.; Irwin, J.H.; Price, T.D. Speciation by distance in a ring species. Science 2005, 307, 414–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watabe, H.; Hashimoto, J. A new species of the genus Rimicaris (Alvinocarididae: Caridea: Decapoda) from the active hydrothermal vent field, “Kairei Field,” on the Central Indian Ridge, the Indian Ocean. Zool. Sci. 2002, 19, 1167–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, W.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Ye, Y.; Xu, K. Sequence comparison of the mitochondrial genomes of five caridean shrimps of the infraorder Caridea: Phylogenetic implications and divergence time estimation. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrbek, T.; Meyer, A. Closing of the Tethys Sea and the phylogeny of Eurasian killifishes (Cyprinodontiformes: Cyprinodontidae). J. Evol. Biol. 2003, 16, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, S.; Ugolini, A.; Momtazi, F.; Hou, Z. Tethyan closure drove tropical marine biodiversity: Vicariant diversification of intertidal crustaceans. J. Biogeogr. 2018, 45, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialik, O.M.; Frank, M.; Betzler, C.; Zammit, R.; Waldmann, N.D. Two-step closure of the Miocene Indian Ocean Gateway to the Mediterranean. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agiadi, K.; Hohmann, N.; Gliozzi, E.; Thivaiou, D.; Bosellini, F.R.; Taviani, M.; Bianucci, G.; Collareta, A.; Londeix, L.; Faranda, C.; et al. Late Miocene transformation of Mediterranean Sea biodiversity. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadp1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Z.; Li, S. Tethyan changes shaped aquatic diversification. Biol. Rev. 2018, 93, 874–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, Y.J.; Kim, M.-S.; Lee, W.-K.; Yoon, H.; Moon, I.; Jung, J.; Ju, S.-J. Niche partitioning of hydrothermal vent fauna in the North Fiji Basin, Southwest Pacific inferred from stable isotopes. Mar. Biol. 2022, 169, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteegh, E.A.; Van Dover, C.L.; Van Audenhaege, L.; Coleman, M. Multiple nutritional strategies of hydrothermal vent shrimp (Rimicaris hybisae) assemblages at the Mid-Cayman Rise. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2023, 192, 103915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.B.; Rona, P.A. Two new caridean shrimps (Bresiliidae) from a hydrothermal field on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. J. Crustac. Biol. 1986, 6, 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, C.; Petersen, J.M.; Werner, J.; Teeling, H.; Huang, S.; Glöckner, F.O.; Golyshina, O.V.; Dubilier, N.; Golyshin, P.N.; Jebbar, M.; et al. The gill chamber epibiosis of deep-sea shrimp Rimicaris exoculata: An in-depth metagenomic investigation and discovery of Zetaproteobacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 16, 2723–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methou, P.; Hernández-Ávila, I.; Cathalot, C.; Cambon-Bonavita, M.-A.; Pradillon, F. Population structure and environmental niches of Rimicaris shrimps from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2022, 684, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dover, C. Trophic relationships among invertebrates at the Kairei hydrothermal vent field (Central Indian Ridge). Mar. Biol. 2002, 141, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methou, P.; Hikosaka, M.; Chen, C.; Watanabe, H.K.; Miyamoto, N.; Makita, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Jenkins, R.G. Symbiont community composition in Rimicaris kairei shrimps from Indian Ocean vents with notes on mineralogy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e00185-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, Y.J.; Kim, M.-S.; Kim, S.-J.; Kim, D.; Ju, S.-J. Carbon sources and trophic interactions of vent fauna in the Onnuri Vent Field, Indian Ocean, inferred from stable isotopes. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2022, 182, 103683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.K.; Chen, C.; Marie, D.P.; Takai, K.; Fujikura, K.; Chan, B.K. Phylogeography of hydrothermal vent stalked barnacles: A new species fills a gap in the Indian Ocean ‘dispersal corridor’ hypothesis. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 172408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Q.; Chen, C.; Sun, J.; Liang, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, C.; Li, M.; Xin, S.; Zhang, D.; et al. Genetic Structure in a Trans-Oceanic Hot Vent Mussel Reveals Four Metapopulations with Implications for Conservation. J. Biogeogr. 2025, 52, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, A.D.; Zelnio, K.; Saleu, W.; Schultz, T.F.; Carlsson, J.; Cunningham, C.; Vrijenhoek, R.C.; Van Dover, C.L. The spatial scale of genetic subdivision in populations of Ifremeria nautilei, a hydrothermal-vent gastropod from the southwest Pacific. BMC Evol. Biol. 2011, 11, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, A.D.; Plouviez, S.; Saleu, W.; Alei, F.; Jacobson, A.; Boyle, E.A.; Schultz, T.F.; Carlsson, J.; Van Dover, C.L. Comparative population structure of two deep-sea hydrothermal-vent-associated decapods (Chorocaris sp. 2 and Munidopsis lauensis) from southwestern Pacific back-arc basins. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-K.; Kim, S.-J.; Hou, B.K.; Van Dover, C.L.; Ju, S.-J. Population genetic differentiation of the hydrothermal vent crab Austinograea alayseae (Crustacea: Bythograeidae) in the Southwest Pacific Ocean. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plouviez, S.; LaBella, A.L.; Weisrock, D.W.; von Meijenfeldt, F.B.; Ball, B.; Neigel, J.E.; Van Dover, C.L. Amplicon sequencing of 42 nuclear loci supports directional gene flow between South Pacific populations of a hydrothermal vent limpet. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 6568–6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitarai, S.; Watanabe, H.; Nakajima, Y.; Shchepetkin, A.F.; McWilliams, J.C. Quantifying dispersal from hydrothermal vent fields in the western Pacific Ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2976–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClain, C.R.; Hardy, S.M. The dynamics of biogeographic ranges in the deep sea. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 277, 3533–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lins, L.S.; Ho, S.Y.; Wilson, G.D.; Lo, N. Evidence for Permo-Triassic colonization of the deep sea by isopods. Biol. Lett. 2012, 8, 979–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachraty, C.; Legendre, P.; Desbruyeres, D. Biogeographic relationships among deep-sea hydrothermal vent faunas at global scale. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2009, 56, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, T. Composition and endemism of the deep-sea hydrothermal vent fauna. CBM-Cah. Biol. Mar. 2005, 46, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, P.R.; Grant, B.R. 40 Years of Evolution: Darwin’s Finches on Daphne Major Island; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014; p. 1400851300. [Google Scholar]

- Givnish, T.J. Adaptive radiation versus ‘radiation’ and ‘explosive diversification’: Why conceptual distinctions are fundamental to understanding evolution. New Phytol. 2015, 207, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morinaga, G.; Wiens, J.J.; Moen, D.S. The radiation continuum and the evolution of frog diversity. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.; Serrao, E.A.; Arnaud-Haond, S. Panmixia in a fragmented and unstable environment: The hydrothermal shrimp Rimicaris exoculata disperses extensively along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methou, P.; Michel, L.N.; Segonzac, M.; Cambon-Bonavita, M.-A.; Pradillon, F. Integrative taxonomy revisits the ontogeny and trophic niches of Rimicaris vent shrimps. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 200837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, C.; Herrington, R.; Maslennikov, V.; Zaykov, V. The fossil record of hydrothermal vent communities. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1998, 148, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.A. Hydrocarbon seep and hydrothermal vent paleoenvironments and paleontology: Past developments and future research directions. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2006, 232, 362–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiel, S. The Vent and Seep Biota: Aspects from Microbes to Ecosystems; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 255–277. [Google Scholar]

- Komai, T.; Menot, L.; Segonzac, M. New records of caridean shrimp (Crustacea: Decapoda) from hydrothermally influenced fields off Futuna Island, Southwest Pacific, with description of a new species assigned to the genus Alvinocaridinides Komai & Chan, 2010 (Alvinocarididae). Zootaxa 2016, 4098, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komai, T.; Giguère, T. A new species of alvinocaridid shrimp Rimicaris Williams & Rona, 1986 (Decapoda: Caridea) from hydrothermal vents on the Mariana Back Arc Spreading Center, northwestern Pacific. J. Crustac. Biol. 2019, 39, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breusing, C.; Johnson, S.B.; Mitarai, S.; Beinart, R.A.; Tunnicliffe, V. Differential patterns of connectivity in Western Pacific hydrothermal vent metapopulations: A comparison of biophysical and genetic models. Evol. Appl. 2023, 16, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dover, C.L. Hydrothermal vent ecosystems and conservation. Oceanography 2012, 25, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.; Sun, J.; Xu, Q.; Qian, P.-Y. Structure and connectivity of hydrothermal vent communities along the mid-ocean ridges in the West Indian Ocean: A review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 744874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Watanabe, H.K.; Sun, J.; Bissessur, D.; Zhang, R.; Han, Y.; Sun, D.; et al. Delineating biogeographic regions in Indian Ocean deep-sea vents and implications for conservation. Divers. Distrib. 2022, 28, 2858–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.A.; Molloy, A.; Hanson, N.B.; Böhm, M.; Seddon, M.; Sigwart, J.D. A global red list for hydrothermal vent molluscs. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 713022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschen, R.E.; Collins, P.C.; Tunnicliffe, V.; Carlsson, J.; Gardner, J.P.; Lowe, J.; McCrone, A.; Metaxas, A.; Sinniger, F.; Swaddling, A. A primer for use of genetic tools in selecting and testing the suitability of set-aside sites protected from deep-sea seafloor massive sulfide mining activities. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 122, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene (Length † bp) | Primer | Sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| COI (421 bp) | LCO1490 | 5′-GGT CAA CAA ATC ATA AAG ATA TTG G-3′ | [43] |

| HCO2198 | 5′-TAA ACT TCA GGG TGA CCA AAA AAT CA-3′ | ||

| 16S (429 bp) | 16Sa | 5′-CGC CTG TTT ATC AAA AAC AT-3′ | [44] |

| 16Sb | 5′-CTC CGG TTT GAA CTC AGA TCA-3′ | ||

| H3 (212 bp) | H3F | 5′-ATG GCT CGT ACC AAG CAG ACV GC-3′ | [45] |

| H3R | 5′-ATA TCC TTR GGC ATR ATR GTG AC-3′ |

| Species (No., %) † | R. chacei (5, 0.00) | R. hybisae (6, 0.08) | R. exoculata (10, 0.09) | R. kairei (1, –) | R. variabilis (90, 0.13) | R. cf. variabilis (9, 0.25) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clade I | R. chacei (167, 0.19) | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.61 | |

| R. hybisae (197, 0.19) | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.65 | ||

| Clade II | R. exoculata (246, 0.35) | 7.47 | 7.70 | 0.30 | 0.79 | 0.90 | |

| R. kairei (112, 0.33) | 7.09 | 6.97 | 1.90 | 0.99 | 1.10 | ||

| Clade III | R. variabilis (196, 1.47) | 8.60 | 8.74 | 7.47 | 8.05 | 0.18 | |

| R. cf. variabilis (9, 0.98) | 8.59 | 8.73 | 6.95 | 7.75 | 1.34 | ||

| Gene | Species | N | S | H | Hd | Nd (%) | D | FS | Pairwise FST † | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COI | Clade I | R. chacei | 167 | 18 | 17 | 0.56 | 0.19 | –2.02 * | –14.99 * | – |

| R. hybisae | 197 | 23 | 24 | 0.61 | 0.19 | –2.18 * | –28.13 * | – | ||

| Overall | 364 | 35 | 37 | 0.75 | 0.27 | –2.16 * | –27.75 * | 0.472 * | ||

| Clade II | R. exoculata | 246 | 36 | 38 | 0.83 | 0.35 | –2.13 * | –27.10 * | – | |

| R. kairei | 112 | 36 | 37 | 0.79 | 0.33 | –2.43 * | –28.56 * | – | ||

| Overall | 358 | 56 | 75 | 0.90 | 1.02 | –1.45 * | –25.15 * | 0.819 * | ||

| Clade III | R. variabilis | 196 | 93 | 128 | 0.96 | 1.47 | –1.89 * | –24.86 * | – | |

| R. cf. variabilis | 9 | 15 | 9 | 1.00 | 0.98 | –1.21 | –5.58 * | – | ||

| Overall | 205 | 95 | 136 | 0.96 | 1.46 | –1.91 * | –24.82 * | 0.100 * | ||

| 16S | Clade III | R. variabilis | 90 | 12 | 13 | 0.36 | 0.13 | –2.07 * | –13.35 * | – |

| R. cf. variabilis | 9 | 4 | 5 | 0.81 | 0.25 | –1.15 | –2.36 * | – | ||

| Overall | 99 | 16 | 17 | 0.41 | 0.14 | –2.25 * | –20.51 * | 0.089 * | ||

| Gene | Clade II (No. of Mitogenomes) | Clade III (No. of Mitogenomes) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. exoculata (1) vs. R. kairei (1) | R. variabilis (4) vs. R. cf. variabilis (1) | |||||||||

| Nucleotide | Amino Acid | Substitution Ratio (Ka/Ks) | Nucleotide | Amino Acid | Substitution Ratio (Ka/Ks) ‡ | |||||

| Length (bp) † | Similarity (%) | Length (no.) | Similarity (%) | Length (bp) †,‡ | Similarity (%) ‡ | Length (No.) ‡ | Similarity (%) ‡ | |||

| ATP6 | 672/672 | 97.62 | 224/224 | 99.55 | 0.06 | 672/672 | 99.00 | 224/224 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| ATP8 | 156/156 | 98.72 | 52/52 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 156/156 | 100.00 | 52/52 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| COI | 1536/1536 | 98.24 | 512/512 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 1536/1536 | 98.23 | 512/512 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| COII | 690/690 | 98.99 | 230/230 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 690/690 | 99.35 | 230/230 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| COIII | 786/786 | 99.11 | 262/262 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 786/786 | 99.75 | 262/262 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| CYTB | 1134/1134 | 98.59 | 378/378 | 99.47 | 0.06 | 1134/1134 | 98.48 | 378/378 | 99.60 | 0.00 |

| ND1 | 939/939 | 97.76 | 313/313 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 939/939 | 98.90 | 313/313 | 99.60 | 0.03 |

| ND2 | 993/993 | 97.89 | 331/331 | 99.40 | 0.05 | 993/993 | 98.36 | 331/331 | 99.62 | 0.03 |

| ND3 | 351/351 | 99.15 | 117/117 | 99.15 | 0.16 | 351/351 | 99.86 | 117/117 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| ND4 | 1338/1338 | 97.82 | 446/446 | 99.55 | 0.02 | 1338/1338 | 98.41 | 446/446 | 99.78 | 0.02 |

| ND4L | 297/297 | 99.00 | 99/99 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 297/297 | 99.50 | 99/99 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| ND5 | 1728/1728 | 97.14 | 576/576 | 99.31 | 0.02 | 1728/1728 | 98.24 | 576/576 | 99.44 | 0.04 |

| ND6 | 513/513 | 96.78 | 171/171 | 97.69 | 0.11 | 513/513 | 98.78 | 171/171 | 99.71 | 0.04 |

| 13 PCGs | 11,133/11,133 | 98.04 | 3711/3711 | 99.57 | 0.03 | 11,133/11,133 | 98.70 | 3711/3711 | 99.76 | 0.03 |

| 12S rRNA | 865/865 | 99.42 | – | – | – | 866/866 | 99.25 | – | – | – |

| 16S rRNA | 1310/1310 | 99.47 | – | – | – | 1310/1309 | 99.62 | – | – | – |

| Control Region | 1005/1004 | 93.84 | – | – | – | 1008/1008 | 97.07 | – | – | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, W.-K.; Cho, S.-Y.; Ju, S.-J.; Kim, S.-J. Three Cases Revealing Remarkable Genetic Similarity Between Vent-Endemic Rimicaris Shrimps Across Distant Geographic Regions. Biology 2026, 15, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020120

Lee W-K, Cho S-Y, Ju S-J, Kim S-J. Three Cases Revealing Remarkable Genetic Similarity Between Vent-Endemic Rimicaris Shrimps Across Distant Geographic Regions. Biology. 2026; 15(2):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020120

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Won-Kyung, Soo-Yeon Cho, Se-Jong Ju, and Se-Joo Kim. 2026. "Three Cases Revealing Remarkable Genetic Similarity Between Vent-Endemic Rimicaris Shrimps Across Distant Geographic Regions" Biology 15, no. 2: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020120

APA StyleLee, W.-K., Cho, S.-Y., Ju, S.-J., & Kim, S.-J. (2026). Three Cases Revealing Remarkable Genetic Similarity Between Vent-Endemic Rimicaris Shrimps Across Distant Geographic Regions. Biology, 15(2), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020120