Genomic and Metabolomic Insights Into the Probiotic Potential of Weissella viridescens

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strain and Culture

2.2. Whole-Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Annotation

2.3. Pangenome and Comparative Genomics

2.4. Metabolomic Profiling of W. viridescens Wv2365 Supernatant

2.5. In Vitro Probiotic Trait Assays

2.5.1. Acid and Bile Salt Tolerance

2.5.2. Auto-Aggregation and Hydrophobicity Assays

2.5.3. Antioxidant Activity Assays

2.6. Safety Evaluation of W. viridescens Wv2365

2.6.1. In Silico Genomic Safety Assessment

2.6.2. In Vitro Phenotypic Safety Assessment

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

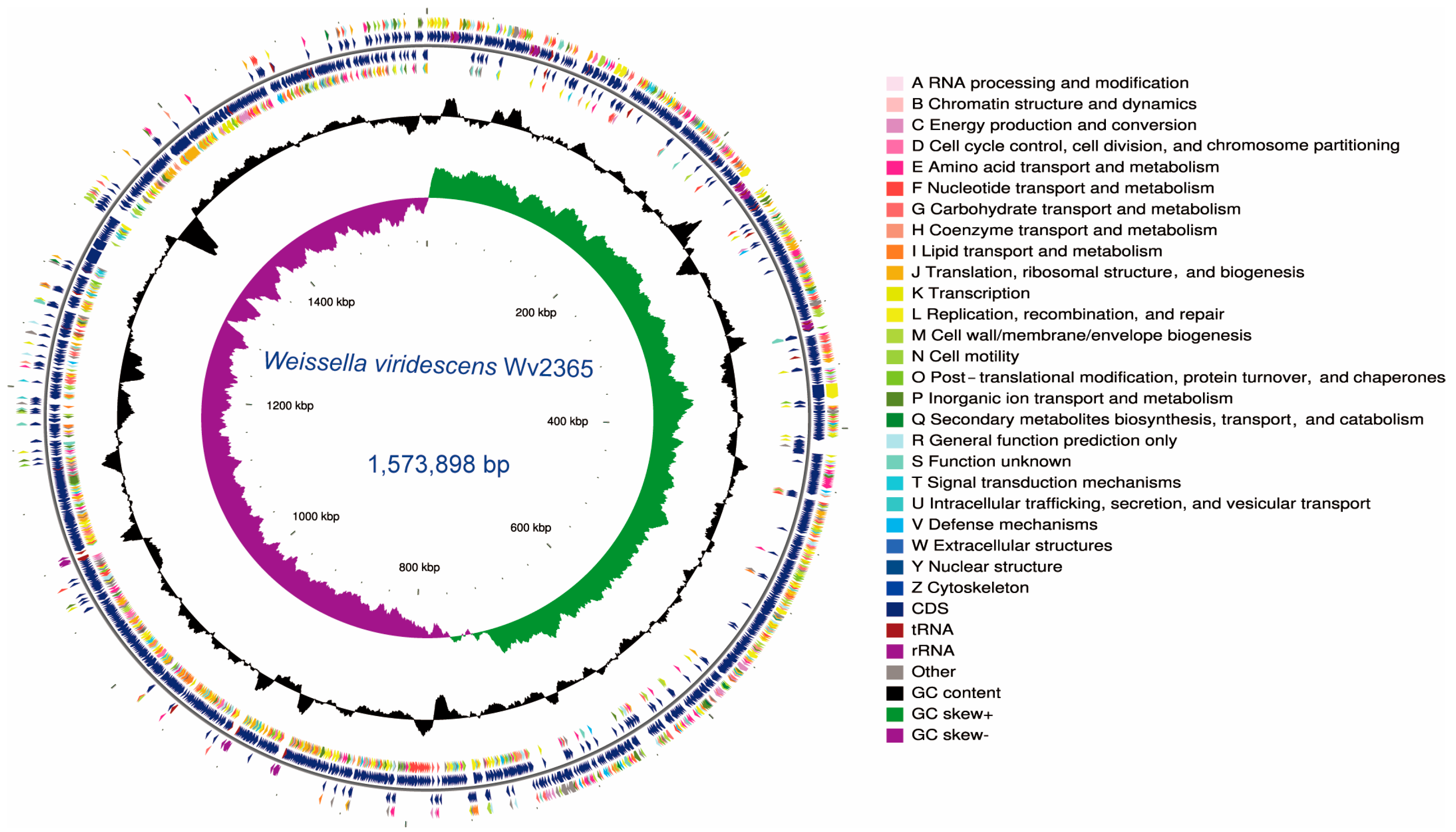

3.1. Genome Features of W. Viridescens Wv2365

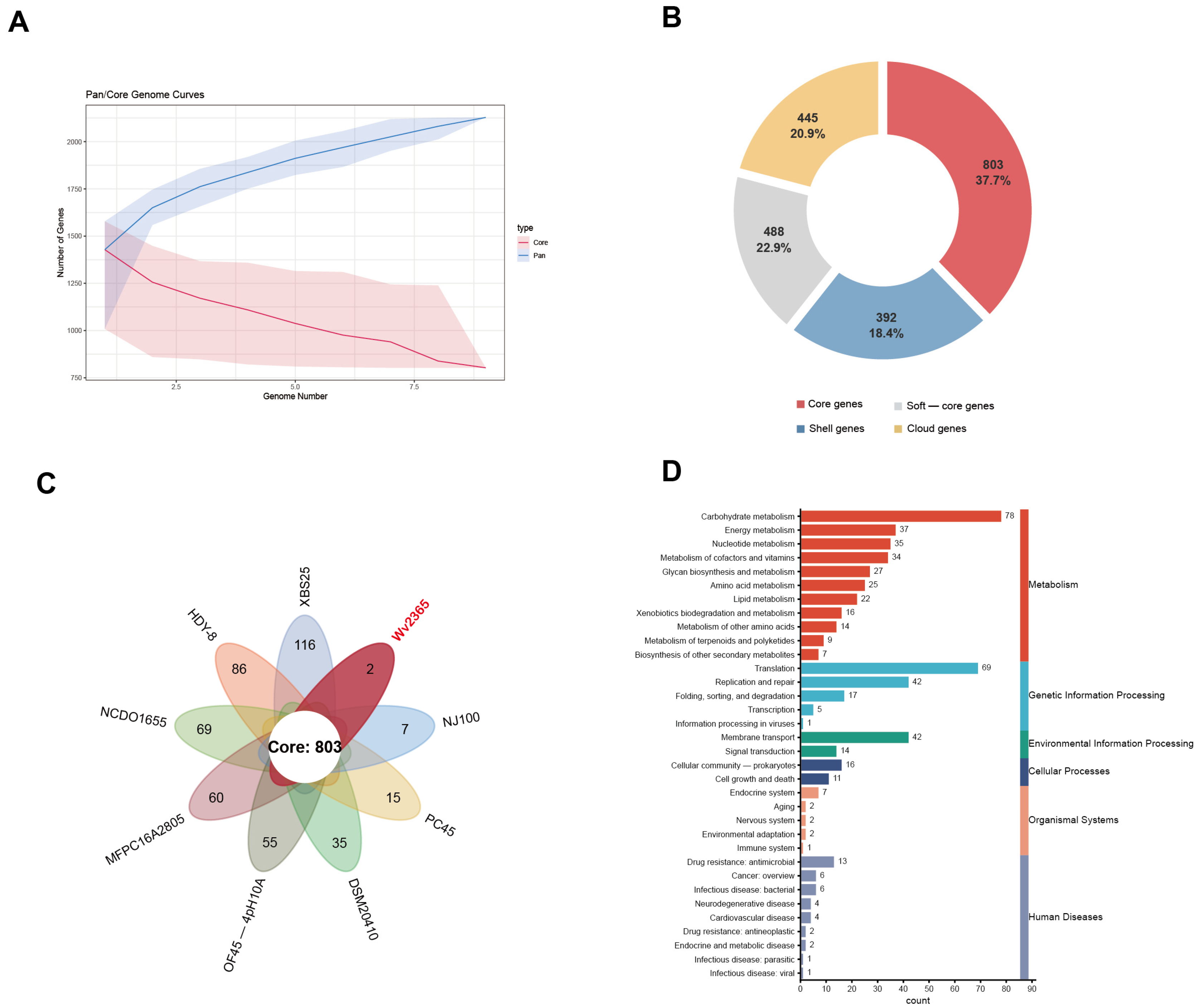

3.2. Pangenome Analysis of the W. viridescens Dataset

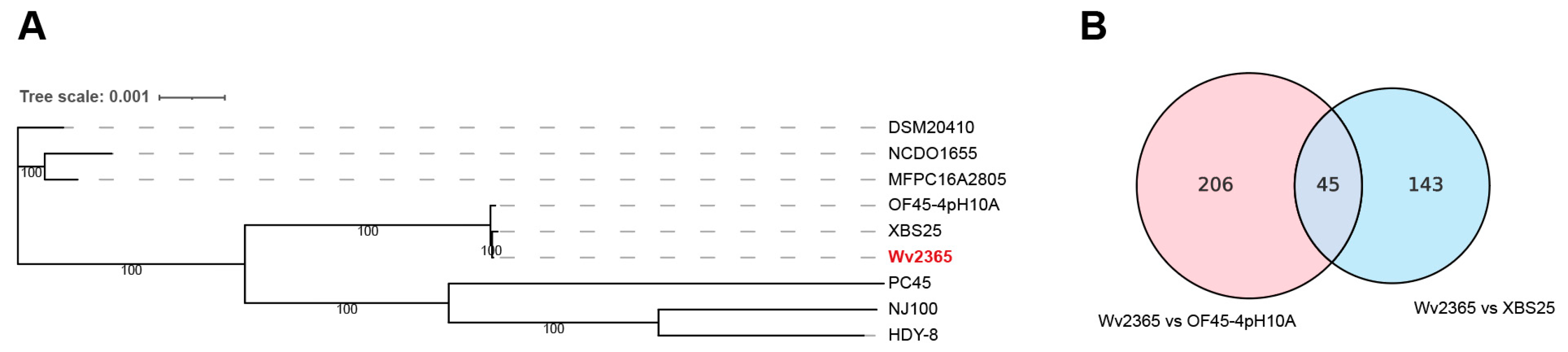

3.3. Phylogenetic Placement and SNV Comparison of Wv2365

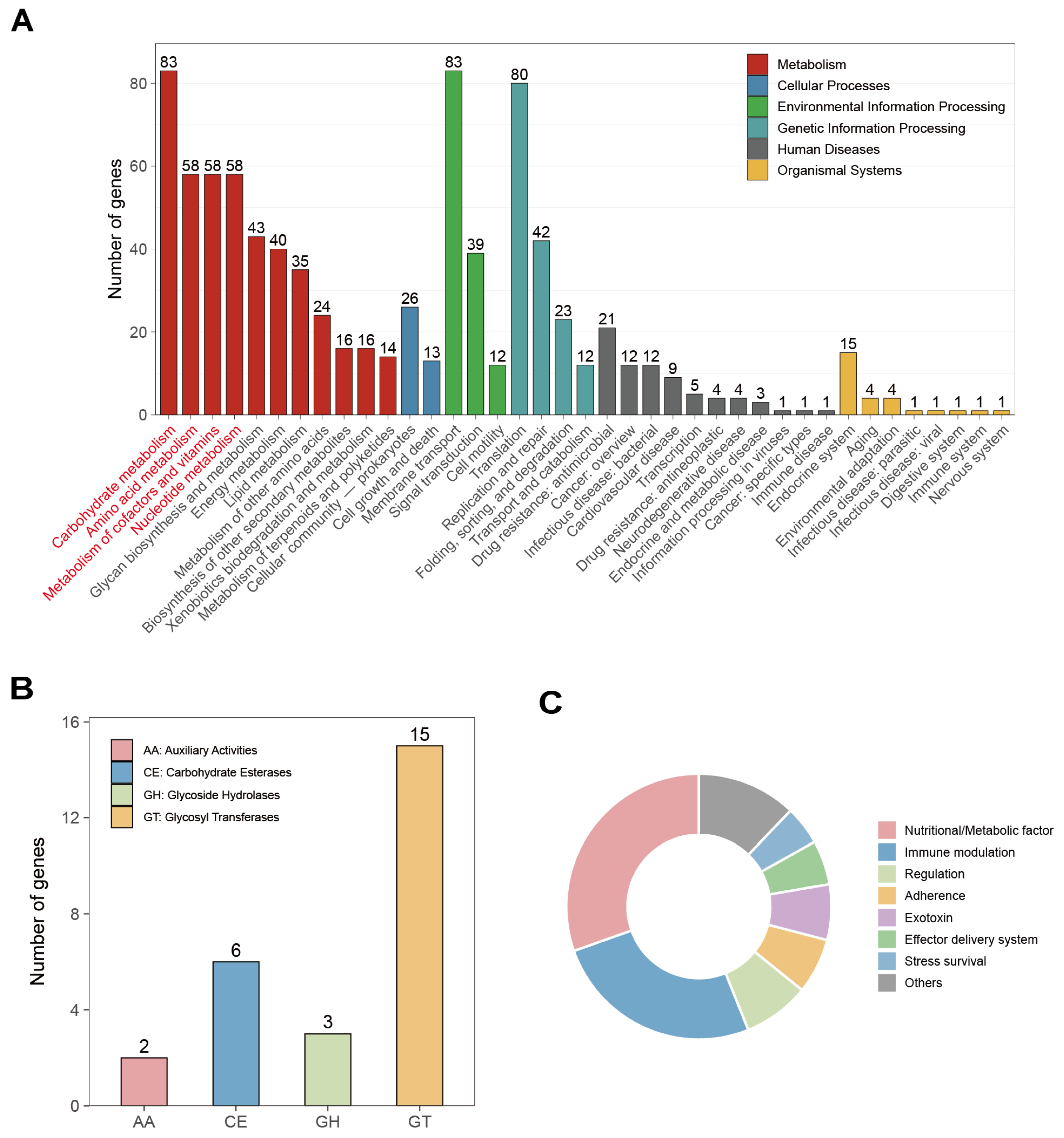

3.4. Functional Genome Annotation of W. Viridescens Wv2365

3.5. Metabolomic Profiling of W. viridescens Wv2365 Culture Supernatant

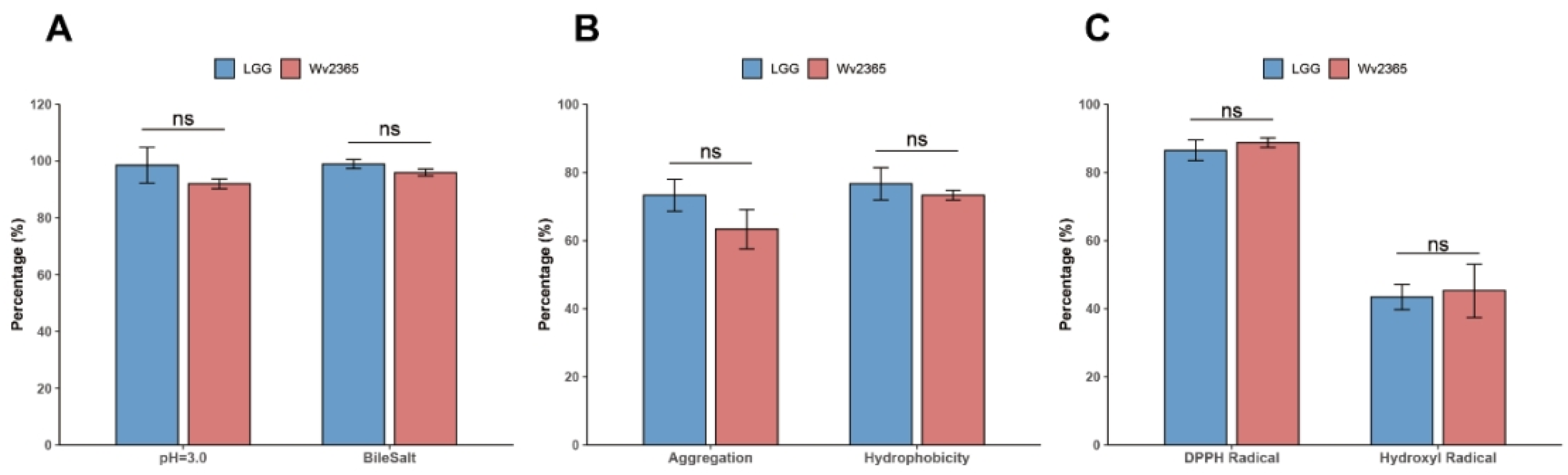

3.6. In Vitro Probiotic Traits of W. viridescens Wv2365

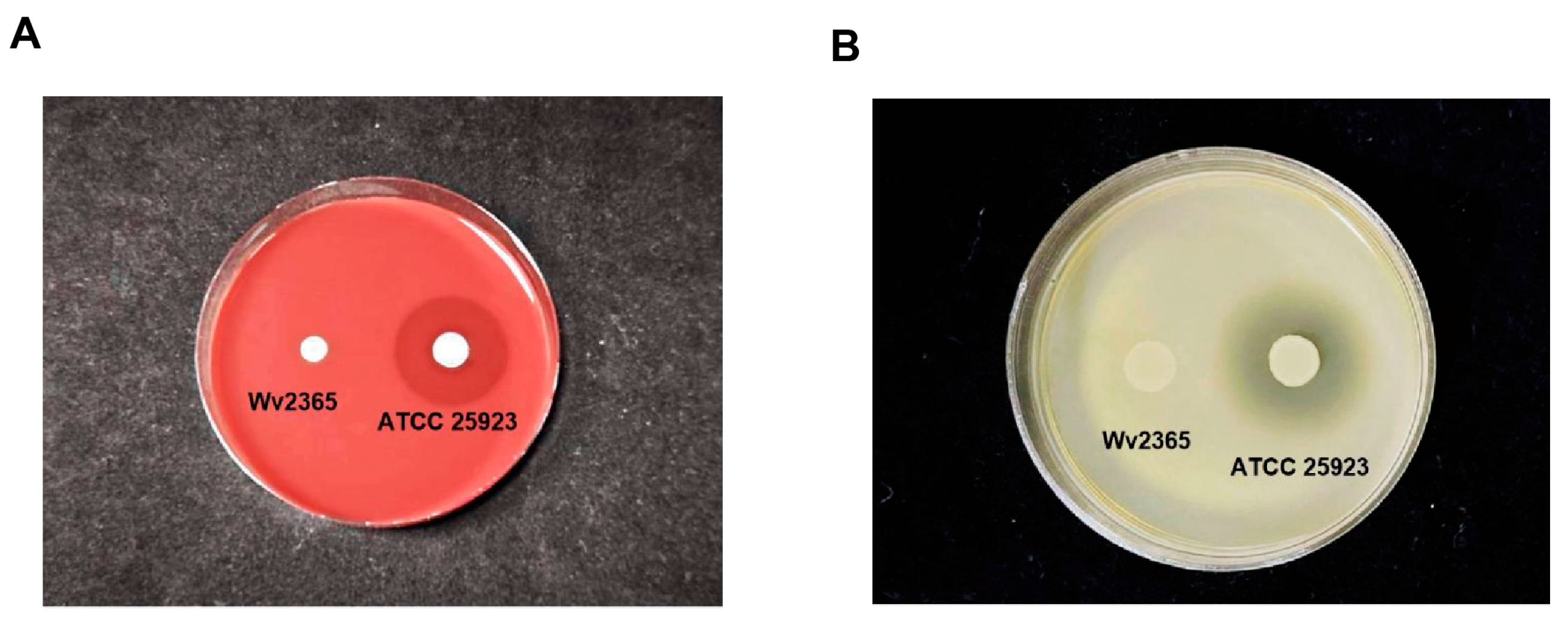

3.7. Safety Evaluation of Results W. viridescens Wv2365

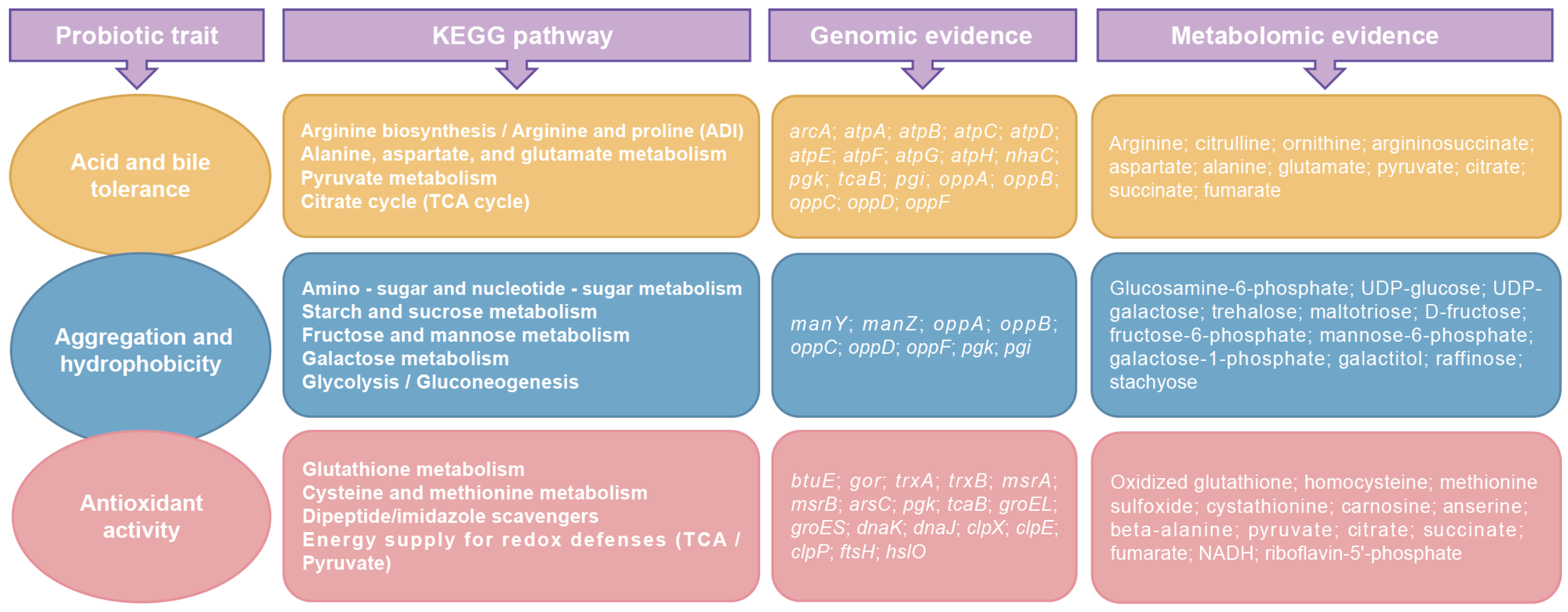

3.8. Overview of Probiotic Traits of W. viridescens Wv2365 as Supported by Multi-Omics Evidence

4. Discussion

4.1. Conserved Genomic Architecture with Strain-Level Diversification in W. viridescens

4.2. Genomic and Metabolomic Evidence for Efficient Carbohydrate Utilization by Wv2365

4.3. Extracellular Metabolite Profiles Link Active Metabolism to Functional Traits in Wv2365

4.4. Integrated Genomic and Metabolomic Evidence Underpin Probiotic-Relevant Phenotypes

4.5. In Vitro Phenotypic Evidence Supports the Probiotic Potential of Wv2365

4.6. Integrated Genome- and Phenotype-Based Safety Assessment of Wv2365

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LAB | lactic acid bacterium |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| CGMCC | China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center |

| COGs | Clusters of Orthologous Groups |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| TCA | tricarboxylic acid |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| CAZymes | Carbohydrate-active enzymes |

| VFDB | Virulence Factor Database |

| PHI-base | Pathogen–Host Interaction database |

| CARD | Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

References

- Collins, M.D.; Samelis, J.; Metaxopoulos, J.; Wallbanks, S. Taxonomic Studies on Some Leuconostoc-like Organisms from Fermented Sausages: Description of a New Genus Weissella for the Leuconostoc paramesenteroides Group of Species. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1993, 75, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, V.; Quero, G.M.; Cho, G.-S.; Kabisch, J.; Meske, D.; Neve, H.; Bockelmann, W.; Franz, C.M.A.P. The Genus Weissella: Taxonomy, Ecology and Biotechnological Potential. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvester, M.E.; Dicks, L.M.T. Identification of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Human Vaginal Secretions. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2003, 83, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitake, D.; Devi, P.B.; Shetty, P.H. Overview of Exopolysaccharides Produced by Weissella Genus—A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 2964–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.K.; Devi, P.B.; Reddy, G.B.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Kavitake, D.; Shetty, P.H. Biosynthesis, Classification, Properties, and Applications of Weissella Bacteriocins. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1406904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics Consensus Statement on the Scope and Appropriate Use of the Term Probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, H.; Beresford, T.P.; Cotter, P.D. Health Benefits of Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) Fermentates. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.E.; Merenstein, D.J.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Rastall, R.A. Probiotics and Prebiotics in Intestinal Health and Disease: From Biology to the Clinic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurso, L. Thirty Years of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG: A Review. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2019, 53, S1–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Zheng, L.; Li, J.; Hong, Y.; Liang, P.; Kwok, L.-Y.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H. iProbiotics: A Machine Learning Platform for Rapid Identification of Probiotic Properties from Whole-Genome Primary Sequences. Brief. Bioinf. 2022, 23, bbab477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhegwu, C.C.; Anumudu, C.K. Probiotic Potential of Traditional and Emerging Microbial Strains in Functional Foods: From Characterization to Applications and Health Benefits. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K.M.; Lucid, A.; Arendt, E.K.; Sleator, R.D.; Lucey, B.; Coffey, A. Genomics of Weissella cibaria with an Examination of Its Metabolic Traits. Microbiology 2015, 161, 914–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakos, I.; Paramithiotis, S.; Mataragas, M. Functional and Safety Characterization of Weissella paramesenteroides Strains Isolated from Dairy Products through Whole-Genome Sequencing and Comparative Genomics. Dairy 2022, 3, 799–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, R.; Wang, R.; Lu, Y.; Xu, M.; Lin, X.; Lan, R.; Zhang, S.; Tang, H.; Fan, Q.; et al. Weissella viridescens Attenuates Hepatic Injury, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation in a Rat Model of High-Fat Diet-Induced MASLD. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving Bacterial Genome Assemblies from Short and Long Sequencing Reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-Mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, V.; Golaconda Ramulu, H.; Drula, E.; Coutinho, P.M.; Henrissat, B. The Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes Database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucl. Acids Res. 2014, 42, D490–D495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Ouk Kim, Y.; Park, S.-C.; Chun, J. OrthoANI: An Improved Algorithm and Software for Calculating Average Nucleotide Identity. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1100–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.J.; Cummins, C.A.; Hunt, M.; Wong, V.K.; Reuter, S.; Holden, M.T.G.; Fookes, M.; Falush, D.; Keane, J.A.; Parkhill, J. Roary: Rapid Large-Scale Prokaryote Pan Genome Analysis. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3691–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2—Approximately Maximum-Likelihood Trees for Large Alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for Taxonomy-Based Analysis of Pathways and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D587–D592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar-Lalanne, G.; Rivera-Espinoza, Y.; Reyes Méndez, A.I.; Hernández-Sánchez, H. In Vitro Evaluation of the Probiotic Potential of Halotolerant Lactobacilli Isolated from a Ripened Tropical Mexican Cheese. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2013, 5, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, D.; Rzepkowska, A.; Radawska, A.; Zieliński, K. In Vitro Screening of Selected Probiotic Properties of Lactobacillus Strains Isolated from Traditional Fermented Cabbage and Cucumber. Curr. Microbiol. 2015, 70, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, D. Assessing the Safety and Probiotic Characteristics of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus X253 via Complete Genome and Phenotype Analysis. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, L. Comprehensive Evaluation of Probiotic Property, Hypoglycemic Ability and Antioxidant Activity of Lactic Acid Bacteria. Foods 2022, 11, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zheng, D.; Zhou, S.; Chen, L.; Yang, J. VFDB 2022: A General Classification Scheme for Bacterial Virulence Factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D912–D917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zankari, E.; Hasman, H.; Cosentino, S.; Vestergaard, M.; Rasmussen, S.; Lund, O.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Larsen, M.V. Identification of Acquired Antimicrobial Resistance Genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2640–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P.; Huynh, W.; Chalil, R.; Smith, K.W.; Raphenya, A.R.; Wlodarski, M.A.; Edalatmand, A.; Petkau, A.; Syed, S.A.; Tsang, K.K.; et al. CARD 2023: Expanded Curation, Support for Machine Learning, and Resistome Prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D690–D699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Methods for Antimicrobial Dilution and Disk Susceptibility Testing of Infrequently Isolated or Fastidious Bacteria, 3rd ed.; CLSI Guideline M45; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP); Rychen, G.; Aquilina, G.; Azimonti, G.; Bampidis, V.; de Lourdes Bastos, M.; Bories, G.; Chesson, A.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Flachowsky, G.; et al. Guidance on the Characterisation of Microorganisms Used as Feed Additives or as Production Organisms. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monika; Savitri; Kumar, V.; Kumari, A.; Angmo, K.; Bhalla, T.C. Isolation and Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Traditional Pickles of Himachal Pradesh, India. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.C.; Coelho, M.C.; Todorov, S.D.; Franco, B.D.G.M.; Dapkevicius, M.L.E.; Silva, C.C.G. Technological Properties of Bacteriocin-Producing Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Pico Cheese an Artisanal Cow’s Milk Cheese. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 116, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhurst, M.A.; Harrison, E.; Hall, J.P.J.; Richards, T.; McNally, A.; MacLean, C. The Ecology and Evolution of Pangenomes. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R1094–R1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rossum, T.; Ferretti, P.; Maistrenko, O.M.; Bork, P. Diversity within Species: Interpreting Strains in Microbiomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakos, I.; Paramithiotis, S.; Mataragas, M. Comparative Genomic Analysis Reveals the Functional Traits and Safety Status of Lactic Acid Bacteria Retrieved from Artisanal Cheeses and Raw Sheep Milk. Foods 2023, 12, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Gupta, D.; Park, Y.-S. Genome Analysis Revealed a Repertoire of Oligosaccharide Utilizing CAZymes in Weissella confusa CCK931 and Weissella cibaria YRK005. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 32, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinu, F.R.; Villas-Boas, S.G. Extracellular Microbial Metabolomics: The State of the Art. Metabolites 2017, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozzi, F.; de Giori, G.S.; de Valdez, G.F. UDP-Galactose 4-Epimerase: A Key Enzyme in Exopolysaccharide Formation by Lactobacillus casei CRL 87 in Controlled pH Batch Cultures. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 94, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Geng, W.; Li, C.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y. Comparative Genomics of Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens ZW3 and Related Members of Lactobacillus. spp Reveal Adaptations to Dairy and Gut Environments. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovanda, L.; Zhang, W.; Wei, X.; Luo, J.; Wu, X.; Atwill, E.R.; Vaessen, S.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activities of Organic Acids and Their Derivatives on Several Species of Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Bacteria. Molecules 2019, 24, 3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Lu, H.; Zhang, T.; Zeng, W. Characterization of Genomic, Physiological, and Probiotic Features of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum JS21 Strain Isolated from Traditional Fermented Jiangshui. Foods 2024, 13, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. F1F0-ATPase Functions Under Markedly Acidic Conditions in Bacteria; Chakraborti, S., Dhalla, N.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 459–468. ISBN 978-3-319-24780-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Carpenter, C.E.; Broadbent, J.R.; Luo, X. Habituation to organic acid anions induces resistance to acid and bile in Listeria monocytogenes. Meat Sci. 2014, 96, 1152–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najar, I.N.; Sharma, P.; Das, R.; Mondal, K.; Singh, A.K.; Radha, A.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, S.; Thakur, N.; Gandhi, S.G.; et al. Unveiling the Probiotic Potential of the Genus Geobacillus through Comparative Genomics and in Silico Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Lv, M.; Shao, Z.; Hungwe, M.; Wang, J.; Bai, X.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Geng, W. Metabolism Characteristics of Lactic Acid Bacteria and the Expanding Applications in Food Industry. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 612285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zeng, J.; Huang, K.; Wang, J. Structure of the Mannose Transporter of the Bacterial Phosphotransferase System. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 680–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, A.A.; Poulsen, V.K.; Janzen, T.; Buldo, P.; Derkx, P.M.F.; Øregaard, G.; Neves, A.R. Polysaccharide Production by Lactic Acid Bacteria: From Genes to Industrial Applications. Fems Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, S168–S200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessione, E. Lactic Acid Bacteria Contribution to Gut Microbiota Complexity: Lights and Shadows. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsburgh, M.J.; Clements, M.O.; Crossley, H.; Ingham, E.; Foster, S.J. PerR Controls Oxidative Stress Resistance and Iron Storage Proteins and Is Required for Virulence in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 3744–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, F.A.; Díaz, W.A.; Leal, C.A.; Pérez-Donoso, J.M.; Imlay, J.A.; Vásquez, C.C. The Escherichia Coli btuE Gene, Encodes a Glutathione Peroxidase That Is Induced under Oxidative Stress Conditions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 398, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voth, W.; Jakob, U. Stress-Activated Chaperones: A First Line of Defense. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017, 42, 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, M.J.; Veeravalli, K.; Gon, S.; Georgiou, G.; Beckwith, J. Functional Plasticity of a Peroxidase Allows Evolution of Diverse Disulfide-Reducing Pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 6735–6740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xue, W.; Ding, H.; An, C.; Ma, S.; Liu, Y. Probiotic Potential of Lactobacillus Strains Isolated from Fermented Vegetables in Shaanxi, China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 774903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W.; Park, J.Y.; Jeong, H.R.; Heo, H.J.; Han, N.S.; Kim, J.H. Probiotic Properties of Weissella Strains Isolated from Human Faeces. Anaerobe 2012, 18, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Palestino, A.; Gómez-Vargas, R.; Suárez-Quiroz, M.; González-Ríos, O.; Hernández-Estrada, Z.J.; Castellanos-Onorio, O.P.; Alonso-Villegas, R.; Estrada-Beltrán, A.E.; Figueroa-Hernández, C.Y. Probiotic Potential of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Yeast Isolated from Cocoa and Coffee Bean Fermentation: A Review. Fermentation 2025, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krausova, G.; Hyrslova, I.; Hynstova, I. In Vitro Evaluation of Adhesion Capacity, Hydrophobicity, and Auto-Aggregation of Newly Isolated Potential Probiotic Strains. Fermentation 2019, 5, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Wang, J. Oxidative Stress Tolerance and Antioxidant Capacity of Lactic Acid Bacteria as Probiotic: A Systematic Review. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1801944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surachat, K.; Kantachote, D.; Wonglapsuwan, M.; Chukamnerd, A.; Deachamag, P.; Mittraparp-arthorn, P.; Jeenkeawpiam, K. Complete Genome Sequence of Weissella cibaria NH9449 and Comprehensive Comparative-Genomic Analysis: Genomic Diversity and Versatility Trait Revealed. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 826683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A.; Nawaz, M.; Rabbani, M.; Mushtaq, M.H. In-Vitro, In-Vivo and Whole Genome-Based Probe into Probiotic Potential of Weissella viridescens PC-45 against Salmonella Gallinarum. Pak. Veter J. 2024, 45, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Takala, T.M.; Huynh, V.A.; Ahonen, S.L.; Paulin, L.; Björkroth, J.; Sironen, T.; Kant, R.; Saris, P. Comparative Genomics of 40 Weissella paramesenteroides Strains. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1128028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antimicrobial Agent | MIC (µg/mL) Interpretive Criteria | MIC (Wv2365) | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | I | R | |||

| Penicillin | ≤8 | — | — | 0.38 | S |

| Ampicillin | ≤8 | — | — | 0.5 | S |

| Tetracycline | ≤2 | 4 | ≥8 | 1.5 | S |

| Chloramphenicol | ≤8 | 16 | ≥32 | 6 | S |

| Vancomycin | ≤2 | 4–8 | ≥16 | 24 | R |

| Linezolid | ≤4 | — | — | 2 | S |

| Meropenem | ≤1 | 2 | ≥4 | 0.75 | S |

| Levofloxacin | ≤2 | 4 | ≥8 | 1 | S |

| Erythromycin | ≤0.5 | 1–4 | ≥8 | 0.19 | S |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.5 | 1 | ≥2 | 0.25 | S |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Lan, R.; Zhao, R.; Wang, R.; Liu, L.; Xu, J. Genomic and Metabolomic Insights Into the Probiotic Potential of Weissella viridescens. Biology 2026, 15, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010063

Zhang S, Lan R, Zhao R, Wang R, Liu L, Xu J. Genomic and Metabolomic Insights Into the Probiotic Potential of Weissella viridescens. Biology. 2026; 15(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shuwei, Ruiting Lan, Ruiqing Zhao, Ruoshi Wang, Liyun Liu, and Jianguo Xu. 2026. "Genomic and Metabolomic Insights Into the Probiotic Potential of Weissella viridescens" Biology 15, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010063

APA StyleZhang, S., Lan, R., Zhao, R., Wang, R., Liu, L., & Xu, J. (2026). Genomic and Metabolomic Insights Into the Probiotic Potential of Weissella viridescens. Biology, 15(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010063