Invertebrate Communities and Driving Factors Across Woody Debris Types in Temperate Forests, Northern China

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Tree Species and Forest Type Selection

2.3. Collection of Woody Debris and Soil Samples

2.4. Invertebrate Collection

2.5. Determination of Physicochemical Properties of Woody Debris and Soils

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Properties of Woody Debris

3.2. Overview of Invertebrate Survey

3.3. The Effects of Tree Species, Forest Type, and Decay Class of Woody Debris on Invertebrate Diversity

3.4. Distribution Characteristics of Dominant Invertebrate Groups in Woody Debris

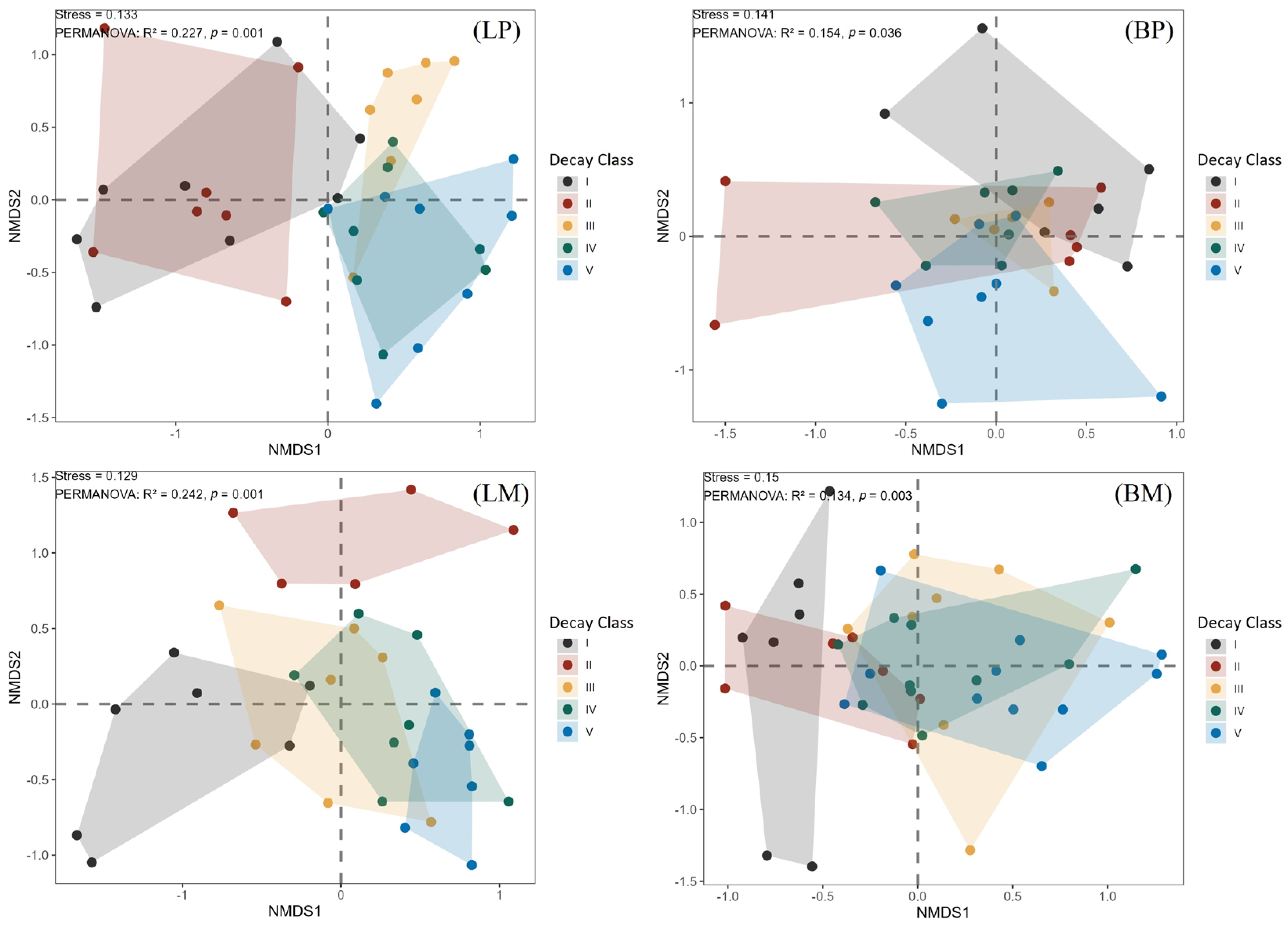

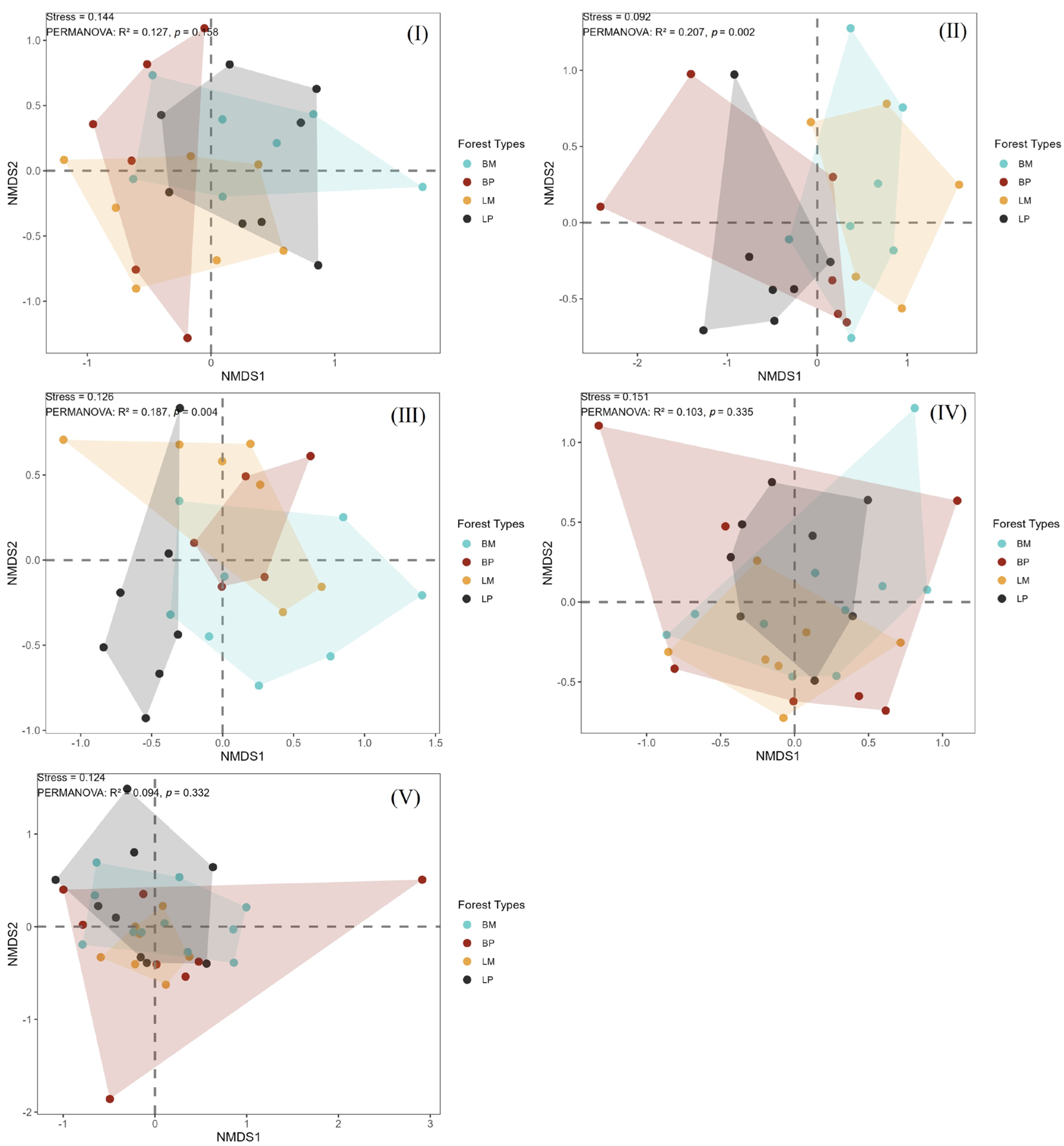

3.5. Distribution of Invertebrates in Woody Debris Based on NMDS Analysis

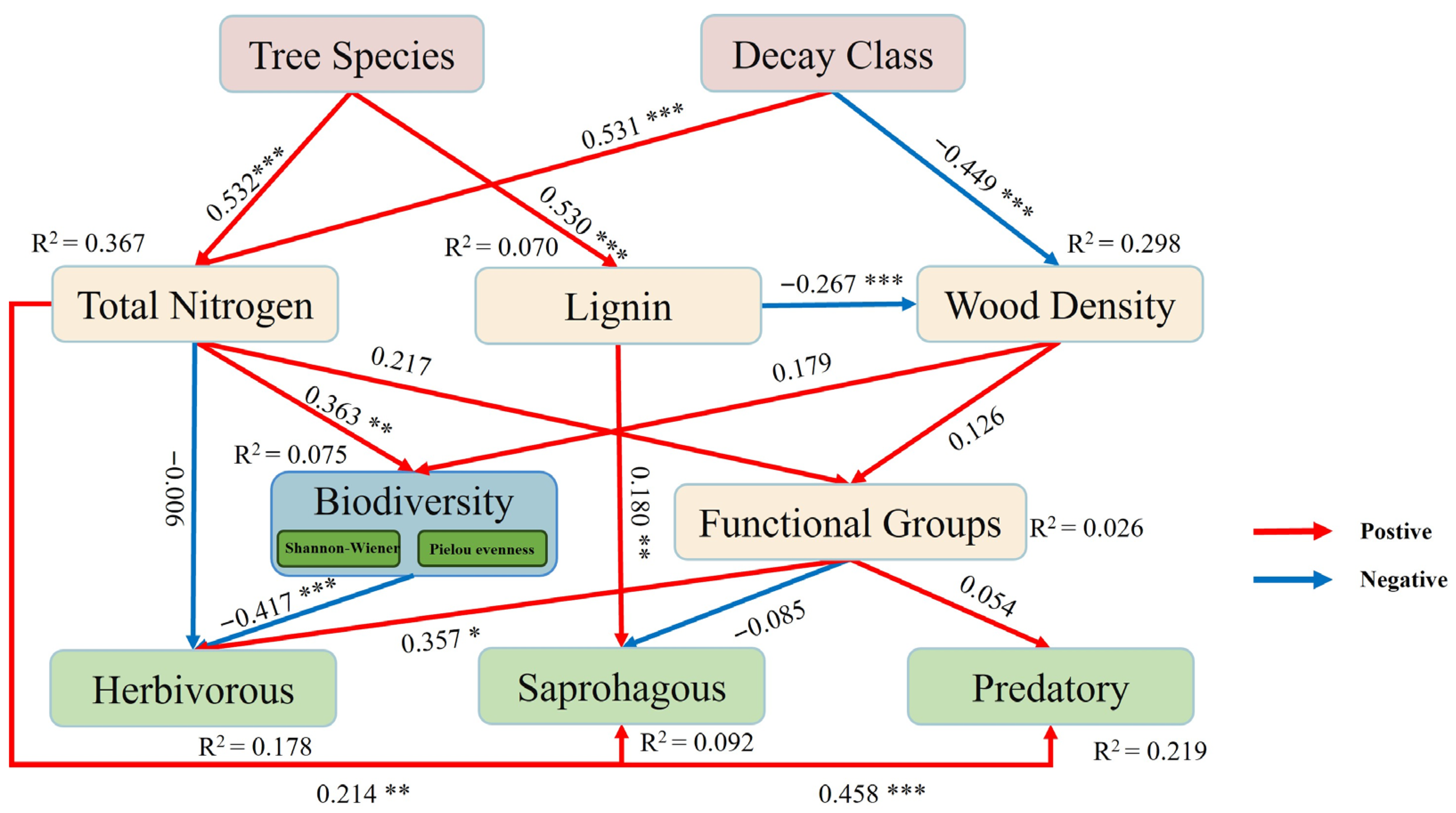

3.6. Interrelationships Between Woody Debris and Invertebrates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Decay Class | Mixed Forest | Pure Forest | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | LM | BP | BM | |

| Soil TN(%) | ||||

| I | 0.76 ± 0.29 Aa | 0.44 ± 0.16 Bb | 0.35 ± 0.12 Ba | 0.37 ± 0.11 Ba |

| II | 0.57 ± 0.31 Ab | 0.49 ± 0.21 Ab | 0.45 ± 0.13 Aa | 0.48 ± 0.26 Aa |

| III | 0.62 ± 0.33 Ab | 0.76 ± 0.48 Aa | 0.39 ± 0.06 Aa | 0.36 ± 0.18 Ab |

| IV | 0.67 ± 0.28 Bb | 0.82 ± 0.13 Ba | 0.34 ± 0.07 Ba | 0.47 ± 0.19 Bb |

| V | 0.99 ± 0.24 Aa | 0.89 ± 0.21 Aa | 0.69 ± 0.44 Ab | 0.71 ± 0.42 Ab |

| Soil TN (CK) | 0.80 ± 0.29 Ba | 0.80 ± 0.29 Ba | 0.48 ± 0.17 Aa | 0.57 ± 0.28 Ab |

| Soil TC(%) | ||||

| I | 11.80 ± 3.28 Ba | 8.61 ± 4.93 Aa | 4.38 ± 1.61 Aa | 7.81 ± 7.15 Aa |

| II | 11.06 ± 4.60 Ba | 10.39 ± 5.10 Ba | 5.94 ± 1.97 Aa | 6.47 ± 3.69 Aa |

| III | 8.48 ± 4.89 Aa | 11.64 ± 7.90 Aa | 5.29 ± 1.54 Aa | 4.66 ± 3.10 Aa |

| IV | 9.96 ± 4.36 Ba | 12.38 ± 1.87 Ba | 4.11 ± 0.86 Ba | 6.94 ± 3.78 Ba |

| V | 11.14 ± 4.01 Ba | 13.77 ± 3.93 Ba | 4.56 ± 1.63 Ba | 6.88 ± 3.63 Ba |

| Soil TC (CK) | 11.84 ± 4.58 Ba | 11.84 ± 4.58 Ba | 6.75 ± 2.36 A | 6.67 ± 2.53 Ba |

| Soil C/N | ||||

| I | 19.38 ± 15.74 Aa | 21.37 ± 16.99 Aa | 12.31 ± 0.60 Aa | 22.97 ± 25.78 Aa |

| II | 25.07 ± 19.65 Ab | 24.54 ± 19.66 Aa | 12.93 ± 1.02 Aa | 13.19 ± 0.92 Ab |

| III | 13.20 ± 2.06 Aa | 14.93 ± 1.51 Aa | 13.36 ± 3.07 Aa | 12.36 ± 1.72 Ab |

| IV | 14.89 ± 1.46 Aa | 15.16 ± 1.46 Aa | 12.10 ± 0.68 Ba | 14.01 ± 1.86 Ab |

| V | 11.88 ± 4.34 Aa | 15.39 ± 0.87 Aa | 8.93 ± 4.57 Bb | 10.98 ± 3.98 Ab |

| Soil C/N (CK) | 14.67 ± 1.34 Aa | 14.67 ± 1.34 Aa | 13.93 ± 1.73 Aa | 12.51 ± 3.31 Ab |

References

- Sverdrup-Thygeson, A.; Ims, R.A. The effect of forest clearcutting in Norway on the community of saproxylic beetles on aspen. Biol. Conserv. 2002, 106, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, J.H.; Sass-Klaassen, U.; Poorter, L.; Geffen, K.; Logtestijn, R.S.; Hal, J.; Goudzwaard, L.; Sterck, F.J.; Klaassen, R.K.; Freschet, G.T.; et al. Controls on coarse wood decay in temperate tree species: Birth of the LOGLIFE experiment. Ambio 2012, 41, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, M.; Franklin, J.; Swanson, F.; Sollins, P.; Gregory, S.; Lattin, J.; Anderson, N.; Cline, S.; Aumen, N.; Sedell, J.; et al. Ecology of coarse woody debris in temperate ecosystems. Adv. Ecol. Res. 2004, 34, 59–234. [Google Scholar]

- Seibold, S.; Rammer, W.; Hothorn, T.; Seidl, R.; Ulyshen, M.D.; Lorz, J.; Cadotte, M.W.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Adhikari, Y.P.; Aragón, R.; et al. The contribution of insects to global forest deadwood decomposition. Nature 2021, 597, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulyshen, M.D. Wood decomposition as influenced by invertebrates. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2016, 91, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jean-François, D.; Ira, H. The ecology of saprophagous macroarthropods (millipedes, woodlice) in the context of global change. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2010, 85, 881–895. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.K.; Ulyshen, M.D.; Horn, S.; Poole, E.M.; Callaham, M.A. Variation in the contribution of macroinvertebrates to wood decomposition as it progresses. Ecosphere 2024, 15, e4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Fonck, M.; Hal, J.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Berg, M.P. Diversity of macro-detritivores in dead wood is influenced by tree species, decay stage and environment. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibold, S.; Wolfgang, W.W.; Didem, A.; Martin, M.G.; Akira, M.; Marc, W.C.; Jonas, H.; Claus, B.; Simon, T. Drivers of community assembly change during succession in wood-decomposing, cbeetle communities. Anim. Ecol. 2023, 92, 965–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, S.; Takeda, H. Succession of soil microarthropod communities during the aboveground and belowground litter decomposition processes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamczyc, J.; Dyderski, M.K.; Horodecki, P.; Jagodzinski, A.M. Mite Communities (Acari, Mesostigmata) in the Initially Decomposed “Litter Islands” of 11 Tree Species in Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) Forest. Forests 2019, 10, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Tuo, B.; Ci, H.; Yan, E.R.; Cornelissen, J.H. Dynamic Feedbacks among Tree Functional Traits, Termite Populations and Deadwood Turnover. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 1578–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Cornelissen, J.H.; Hefting, M.M.; Sass-Klaassen, U.; Richard, S.P.; Jurgen, H.; Goudzwaard, L.; Liu, J.C.; Berg, M.P. The (w)hole story: Facilitation of dead wood fauna by bark beetles? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 95, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulyshen, M.D.; Hanula, J.L. Patterns of saproxylic beetle succession in loblolly pine. Agric. For. Entomol. 2010, 12, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnússon, R.Í.; Tietema, A.; Cornelissen, J.H.; Hefting, M.M.; Kalbitz, K. Tamm Review: Sequestration of carbon from coarse woody debris in forest soils. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 377, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasota, J.; Błońska, E.; Piaszczyk, W.; Wiecheć, M. How the deadwood of different tree species in various stages of decomposition affected nutrient dynamics? J. Soils Sediments 2018, 18, 2759–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Berg, M.P.; Jurgen, H.; Richard, S.P.; Leo, G.; Hefting, M.; Lourens, P.; Frank, J.S.; Cornelissen, J.H. Fauna community convergence during decomposition of deadwood across tree species and forests. Ecosystems 2021, 24, 926–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalie, C. Let sleeping logs lie: Beta diversity increases in deadwood beetle communities over time. J. Anim. Ecol. 2023, 92, 948–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassard, W.B.; Chen, H.Y. Effects of Forest Type and Disturbance on Diversity of Coarse Woody Debris in Boreal Forest. Ecosystems 2008, 11, 1078–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Muys, B.; Berg, M.P.; Hefting, M.M.; Richard, S.P.; Jurgen, H.; Cornelissen, J.H. Earthworms are not just “earth” worms: Multiple drivers to large diversity in Deadwood. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 530, 120746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.T.; Li, Y.; Xiao, J.J.; Dai, Z.L. Characteristics of soil fauna community of three plantations in the western Sichuan Basin border of China. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2013, 19, 618–622. [Google Scholar]

- Plath, E.; Fischer, K. Spruce dieback as chance for biodiversity: Standing deadwood promotes beetle diversity in post-disturbance stands in western Germany. J. Insect Conserv. 2024, 28, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, N.; Jonas, H.; Rafael, A.; Didem, A.; Christian, A.; Peter, S.; Sebastian, S.; Michael, S.; Wolfgang, W.W.; Martin, M.G.; et al. Hierarchical trait filtering at different spatial scales determines beetle assemblages in deadwood. Funct. Ecol. 2022, 36, 2929–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piętka, S.; Sotnik, A.; Damszel, M.; Sierota, Z. Coarse woody debris and wood-colonizing fungi differences between a reserve stand and a managed forest in the Taborz region of Poland. J. For. Res. 2019, 30, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas, F.; Dirk, K.; Tobias, M.; Marcus, D.; Renate, R.; Björn, H.; Eduard, L.K. Diversity and Interactions of Wood-Inhabiting Fungi and Beetles after Deadwood Enrichment. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143566. [Google Scholar]

- Oettel, J.; Zolles, A.; Gschwantner, T.; Kindermann, G.; Manfred, K.S.; Gossner, M.M.; Essl, F. Dynamics of standing deadwood in Austrian forests under varying forest management and climatic conditions. J. Appl. Ecol. 2023, 60, 696–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spies, T.A.; Franklin, J.F.; Thomas, T.B. Coarse woody debris in douglas-fir forests of western oregon and Washington. Ecology 1988, 69, 1689–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouvinen, S.; Kuuluvainen, T.; Karjalainen, L. Coarse woody debris in old Pinus sylvestris dominated forests along a geographic and human impact gradient in boreal Fennoscandia. Can. J. For. Res. 2002, 32, 2184–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, M.E.; Sexton, J. Guidelines for Measurements of Woody Detritus in Forest Ecosystems; No. eattle; US LTER Publication: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; pp. 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, W.Y. Pictorical Key to Soil Animals of China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1998. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.R.; Dou, P.P.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H.J.; Lin, D.M. Characteristics and influencing factors of surface soil fauna community in a subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forest of Jinfo Mountain. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 7602–7610, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.J.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.J.; Liu, Z.G.; Zhang, D.J. Characteristics of soil faunal community structure before and after the rotation period of Eucalyptus grandis plantations with various densities. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 808–821, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, S.; Xiang, W.; Gou, M.; Chen, L.; Lei, P.; Xiao, W.; Deng, X.; Zeng, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, T.; et al. Stability in subtropical forests: The role of tree species diversity, stand structure, environmental and socio-economic conditions. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2020, 30, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Yan, Q.; Yuan, J.; Li, R.; Lü, X.; Liu, S.; Zhu, J. Temporal Effects of Thinning on the Leaf C:N:P Stoichiometry of Regenerated Broadleaved Trees in Larch Plantations. Forests 2020, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, S.D.; Groffman, P.M.; Mitchell, M.J. Leaching of dissolved organic carbon, dissolved organic nitrogen, and other solutes from coarse woody debris and litter in a mixed forest in New York State. Biogeochemistry 2005, 74, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajtha, K.; Crow, S.E.; Yano, Y.; Kaushal, S.S.; Sulzman, E.; Sollins, P.; Spears, J.D. Detrital controls on soil solution N and dissolved organic matter in soils: A field experiment. Biogeochemistry 2005, 76, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Yin, R.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Z.F.; Liu, Y.; He, S.Q.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Wang, L.X.; Liu, S.N.; et al. Temperature and moisture modulate the contribution of soil fauna to litter decomposition via different pathways. Ecosystems 2020, 24, 1142–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; Tosi, V. Deadwood density variation with decay class in seven tree speciesofthe ltalian Alps. Scand. J. For. Res. 2010, 25, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorelli, R.; Paletto, A.; Agnelli, A.E.; Lagomarsino, A.; Meo, I.D. Microbial communities associated with decomposing deadwood of downy birch in a natural forest in Khibiny Mountains (Kola Peninsula, Russian Federation). For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 455, 117643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.X.; Xiang, W.H.; Wu, H.L.; Lei, P.F.; Zhang, S.L.; Ouyang, S.; Deng, X.W.; Fang, X. Tree growth traits and social status affect the wood density of pioneer species in secondary subtropical forest. Ecol Evol 2017, 7, 5366–5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossa, G.G.; Schaefer, D.; Zhang, J.L.; Tao, J.P.; Cao, K.F.; Corlett, R.T.; Cunningham, A.B.; Xu, J.C.; Cornelissen, J.H.; Harrison, R.D. The cover uncovered: Bark control over wood decomposition. J. Ecol. 2018, 106, 2147–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Hefting, M.M.; Berg, M.P.; Richard, S.P.; Hal, J.; Goudzwaard, L.; Liu, J.C.; Sass-klaassen, U.; Sterck, F.J.; Poorter, L.; et al. Is there a tree economics spectrum of decomposability? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 119, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Wende, B.; Strobl, C.; Eugster, M.; Gallenberger, I.; Floren, A.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Linsenmair, K.E.; Weisser, W.W.; Gossner, M.M. Forest management and regional tree composition drive the host preference of saproxylic beetle communities. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Germain, M.; Drapeau, P.; Buddle, M.C. Host-use patterns of saproxylic phloeophagous and xylophagous coleoptera adults and larvae along the decay gradient in standing dead black spruce and aspen. Ecography 2007, 30, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.X.; Cheng, X.Q.; Han, H.R.; Jing, H.Y.; Liu, X.J.; Li, Z.Z. Seasonal variations and thinning effects on soil phosphorus fractions in Larix principis-rupprechtii Mayr. Plantations. Forests 2019, 10, 172. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwel, C.M.; Malcolm, R.J.; Smith, M.S. An integrated model for snag and downed woody debris decay class transitions. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 234, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, F.; Pioli, S.; Lombardi, F.; Fravolini, G.; Marchetti, M.; Tognetti, R. Linking deadwood traits with saproxylic invertebrates and fungi in European forests—A review. iForest-Biogeosci. For. 2018, 11, 423–436. [Google Scholar]

- Laureline, L.; Irene, C.; Camille, M.; Yoan, P.; Wilfried, T.; Lucie, V.; Georges, K. Beyond the role of climate and soil conditions: Living and dead trees matter for soil biodiversity in mountain Forests. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 187, 109194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsell, M.; Hansson, J.; Wedmo, L. Diversity of saproxylic beetle species in logging residues in Sweden—Comparisons between tree species and diameters. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 138, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andringa, J.I.; Zuo, J.; Berg, M.P.; Klein, R.; Veer, J.; Geus, R.; Beaumont, M.; Goudzwaard, L.; Hal, J.; Broekman, R.; et al. Combining tree species and decay stages to increase invertebrate diversity in dead wood. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 441, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Forest Type | Plot Number | Age (Year) | Longitude E | Altitude N | Density (Tree/hm2) | DBH (cm) | Tree Height (m) | Canopy Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Larch Forest | L1 | 43a | 117°50′ | 42°47′ | 447 | 21.60 | 13.10 | 0.65 |

| L2 | 46a | 117°50′ | 42°47′ | 631 | 25.70 | 13.80 | 0.86 | |

| L3 | 44a | 117°53′ | 42°48′ | 382 | 22.10 | 13.20 | 0.60 | |

| L4 | 42a | 117°44′ | 42°43′ | 462 | 21.53 | 17.25 | 0.63 | |

| L5 | 42a | 117°42′ | 42°41′ | 586 | 20.14 | 15.85 | 0.78 | |

| L6 | 45a | 117°06′ | 42°44′ | 608 | 25.89 | 19.95 | 0.85 | |

| Birch Forest | B1 | 40a | 117°53′ | 42°49′ | 448 | 17.30 | 11.95 | 0.73 |

| B2 | 42a | 117°32′ | 42°46′ | 486 | 24.21 | 16.30 | 0.68 | |

| B3 | 42a | 117°38′ | 42°45′ | 311 | 22.68 | 17.20 | 0.56 | |

| Larch–Birch Mixed Forest | LB1 | 45a | 117°49′ | 42°47′ | 426 | 25.90 | 14.20 | 0.61 |

| LB2 | 45a | 117°49′ | 42°47′ | 588 | 23.80 | 14.90 | 0.72 | |

| LB3 | 40a | 117°51′ | 42°48′ | 513 | 16.03 | 10.30 | 0.70 | |

| LB4 | 40a | 117°52′ | 42°48′ | 469 | 20.10 | 15.00 | 0.80 | |

| LB5 | 40a | 117°53′ | 42°48′ | 619 | 18.73 | 10.20 | 0.81 | |

| LB6 | 42a | 117°53′ | 42°48′ | 576 | 20.22 | 12.55 | 0.77 | |

| LB7 | 46a | 117°40′ | 42°42′ | 533 | 26.11 | 21.95 | 0.82 | |

| LB8 | 42a | 117°41′ | 42°41′ | 516 | 20.94 | 16.35 | 0.85 | |

| LB9 | 40a | 117°42′ | 42°41′ | 540 | 18.59 | 14.10 | 0.82 | |

| LB10 | 48a | 117°41′ | 42°44′ | 467 | 30.90 | 16.85 | 0.77 |

| Decay Class | Mixed Forest | Pure Forest | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | LM | BP | LP | |

| Moisture Content (%) | ||||

| I | 0.48 ± 0.12 ABa | 0.22 ± 0.04 Aa | 0.40 ± 0.12 Ba | 0.24 ± 0.06 Aa |

| II | 0.59 ± 0.17 Aa | 0.37 ± 0.12 Aa | 0.65 ± 0.14 Aa | 0.29 ± 0.09 Aa |

| III | 0.59 ± 0.14 Aa | 0.43 ± 0.19 Aa | 0.56 ± 0.16 Aa | 0.42 ± 0.08 Aa |

| IV | 0.65 ± 0.17 Aa | 0.54 ± 0.16 Aa | 0.66 ± 0.17 Aa | 0.51 ± 0.18 Aa |

| V | 0.73 ± 0.18 Aa | 0.67 ± 0.09 Aa | 0.72 ± 0.17 Aa | 0.58 ± 0.25 Aa |

| Density (g/cm3) | ||||

| I | 0.32 ± 0.10 Ab | 0.48 ± 0.11 Bc | 0.35 ± 0.07 Ab | 0.49 ± 0.09 Bb |

| II | 0.24 ± 0.11 Aa | 0.43 ± 0.08 Ac | 0.17 ± 0.09 Aa | 0.45 ± 0.10 Bb |

| III | 0.25 ± 0.12 Aa | 0.34 ± 0.12 Ab | 0.25 ± 0.12 Aa | 0.41 ± 0.03 Bb |

| IV | 0.22 ± 0.08 Aa | 0.30 ± 0.11 Ab | 0.23 ± 0.14 Aa | 0.33 ± 0.11 Ba |

| V | 0.20 ± 0.17 Aa | 0.18 ± 0.07 Aa | 0.15 ± 0.11 Aa | 0.28 ± 0.16 Aa |

| Total Nitrogen Content (TN) (%) | ||||

| I | 0.21 ± 0.08 Aa | 0.13 ± 0.07 Aa | 0.21 ± 0.06 Aa | 0.12 ± 0.06 Aa |

| II | 0.42 ± 0.21 Aa | 0.13 ± 0.12 Aa | 0.43 ± 0.19 Aa | 0.13 ± 0.06 Aa |

| III | 0.34 ± 0.14 Aa | 0.31 ± 0.16 Aa | 0.32 ± 0.09 Aa | 0.14 ± 0.06 Aa |

| IV | 0.45 ± 0.10 Aa | 0.41 ± 0.22 Aa | 0.37 ± 0.15 Aa | 0.27 ± 0.16 Aa |

| V | 0.69 ± 0.33 Aa | 0.73 ± 0.21 Aa | 0.50 ± 0.25 Aa | 0.35 ± 0.29 Aa |

| Total Carbon Content (TC) (%) | ||||

| I | 47.97 ± 0.46 Aa | 48.59 ± 0.77 ABa | 47.36 ± 0.94 Aa | 48.58 ± 0.73 Ba |

| II | 48.27 ± 0.98 Aa | 48.38 ± 1.11 Aa | 46.19 ± 3.83 Aa | 48.38 ± 0.75 Aa |

| III | 48.45 ± 1.24 Aa | 49.18 ± 1.56 Aa | 47.51 ± 2.00 Aa | 48.68 ± 0.47 Aa |

| IV | 48.03 ± 1.00 Aa | 48.58 ± 1.48 Aa | 48.09 ± 0.85 Aa | 48.74 ± 2.14 Aa |

| V | 47.54 ± 1.17 Aa | 48.01 ± 1.22 Aa | 47.08 ± 3.26 Aa | 49.32 ± 2.12 Aa |

| C/N | ||||

| I | 259.45 ± 112.63 Ab | 524.32 ± 345.98 Ab | 241.19 ± 71.75 Ab | 518.60 ± 306.01 Aa |

| II | 133.91 ± 48.46 Aa | 561.24 ± 259.09 ABb | 127.84 ± 61.94 Aa | 448.41 ± 166.21 Ba |

| III | 162.59 ± 69.52 Aa | 222.54 ± 158.85 Aa | 159.67 ± 46.92 Aa | 447.86 ± 257.67 Ba |

| IV | 111.28 ± 21.66 Aa | 153.02 ± 82.74 Aa | 150.68 ± 72.20 Aa | 221.85 ± 84.99 Ba |

| V | 84.25 ± 40.19 Aa | 71.61 ± 23.19 Aa | 126.60 ± 83.10 Aa | 298.03 ± 238.65 Ba |

| Lignin Content (%) | ||||

| I | 33.27 ± 9.84 Aa | 23.07 ± 6.18 Aa | 27.40 ± 7.96 Aa | 25.54 ± 4.13 Aa |

| II | 33.41 ± 5.41 Aa | 22.19 ± 7.60 Aa | 27.04 ± 6.07 Aa | 26.28 ± 5.22 Aa |

| III | 29.51 ± 8.25 Aa | 29.15 ± 8.78 Aa | 25.178 ± 7.06 Aa | 21.53 ± 3.44 Aa |

| IV | 31.86 ± 10.32 Aa | 27.31 ± 3.08 Aa | 29.66 ± 3.52 Aa | 25.51 ± 8.25 Aa |

| V | 31.47 ± 4.89 Aa | 30.51 ± 6.71 Aa | 26.44 ± 6.26 Aa | 27.63 ± 8.50 Aa |

| Cellulose Content (%) | ||||

| I | 35.18 ± 3.57 Ab | 32.6.75 ± 5.63 Aa | 32.02 ± 9.20 Aa | 31.13 ± 6.83 Aa |

| II | 30.87 ± 5.99 Aa | 32.2.73 ± 8.71 Aa | 28.78 ± 10.86 Aa | 36.71 ± 4.23 Aa |

| III | 31.14 ± 2.96 Aa | 30.4.39 ± 3.54 Aa | 36.29 ± 7.70 Aa | 35.12 ± 8.87 Aa |

| IV | 30.07 ± 8.44 Aa | 31.5.10 ± 8.48 Aa | 32.06 ± 11.19 Aa | 29.83 ± 5.68 Aa |

| V | 21.65 ± 10.06 Aa | 25.0.44 ± 5.93 Aa | 28.83 ± 12.27 Aa | 25.54 ± 12.42 Aa |

| Taxonomic Group | Number of Individuals | Fraction (%) |

|---|---|---|

| All samples | 4312 | 100 |

| Annelida | 49 | 1.14 |

| Oligochaeta | 49 | 1.14 |

| Arthropoda | 4263 | 98.86 |

| Arachnida | 380 | 8.81 |

| Araneae | 180 | 4.17 |

| Pseudoscorpiones | 27 | 0.63 |

| Opiliones | 173 | 4.01 |

| Diplopoda | 31 | 0.72 |

| Julida | 31 | 0.72 |

| Chilopoda | 572 | 13.27 |

| Scolopendromorpha | 557 | 12.92 |

| Geophilomorpha | 12 | 0.28 |

| Scutigeromorpha | 3 | 0.07 |

| Insecta | 3280 | 76.06 |

| Hemiptera | 46 | 1.07 |

| Psocoptera | 6 | 0.14 |

| Thysanoptera | 82 | 1.90 |

| Coleoptera | 1355 | 31.42 |

| Neuroptera | 7 | 0.16 |

| Lepidoptera | 14 | 0.32 |

| Diptera | 1739 | 40.33 |

| Hymenoptera | 31 | 0.72 |

| df | Shannon–Wiener Index | Pielou’s Index | Individual Density | Group Number | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tree Species | 1 | 1.531 | 0.904 | 8.792 ** | 1.642 |

| Forest Types | 1 | 7.407 ** | 3.06 | 0.08 | 4.726 * |

| Decay class | 4 | 1.421 | 1.143 | 25.415 *** | 4.689 ** |

| Tree Species × Forest Types | 1 | 0.418 | 0.051 | 0.689 | 0.553 |

| Tree Species × Decay Class | 4 | 2.883 * | 1.084 | 1.205 | 2.868 * |

| Forest Types × Decay Class | 4 | 1.516 | 1.494 | 1.991 | 0.520 |

| Tree Species × Forest Types × Decay class | 4 | 1.384 | 0.927 | 1.341 | 1.187 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dong, J.; Qi, Z.; Cao, M.; Wang, Z.; Ji, X.; Yang, J. Invertebrate Communities and Driving Factors Across Woody Debris Types in Temperate Forests, Northern China. Biology 2026, 15, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010043

Dong J, Qi Z, Cao M, Wang Z, Ji X, Yang J. Invertebrate Communities and Driving Factors Across Woody Debris Types in Temperate Forests, Northern China. Biology. 2026; 15(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Jinkai, Zhiwei Qi, Mingliang Cao, Zijin Wang, Xueqian Ji, and Jinyu Yang. 2026. "Invertebrate Communities and Driving Factors Across Woody Debris Types in Temperate Forests, Northern China" Biology 15, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010043

APA StyleDong, J., Qi, Z., Cao, M., Wang, Z., Ji, X., & Yang, J. (2026). Invertebrate Communities and Driving Factors Across Woody Debris Types in Temperate Forests, Northern China. Biology, 15(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010043