Multi-Omics Integration Identifies the Cholesterol Metabolic Enzyme DHCR24 as a Key Driver in Breast Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overall Research Strategy

2.2. Study Design and Data Sources

2.2.1. Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization

2.2.2. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.3. In Vitro Experiments

2.3.1. Immunohistochemical (IHC) Staining

2.3.2. Cell Culture

2.3.3. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

2.3.4. Western Blotting (WB)

2.3.5. Lentiviral Knockdown

2.3.6. Functional Assays

2.4. Molecular Mechanism Investigation

2.4.1. Differential Expression Analysis

2.4.2. Enrichment Analyses

2.4.3. Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Construction

2.4.4. EMT-Associated Gene Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. AI Assistance Disclosure

3. Results

3.1. Genetic and Clinical Evidence Links Cholesterol Metabolism and DHCR24 to BC

3.1.1. Causal Link Between Cholesterol and BC Risk

3.1.2. Multi-Omics Screening Identifies DHCR24 as a Key Mediator in BC

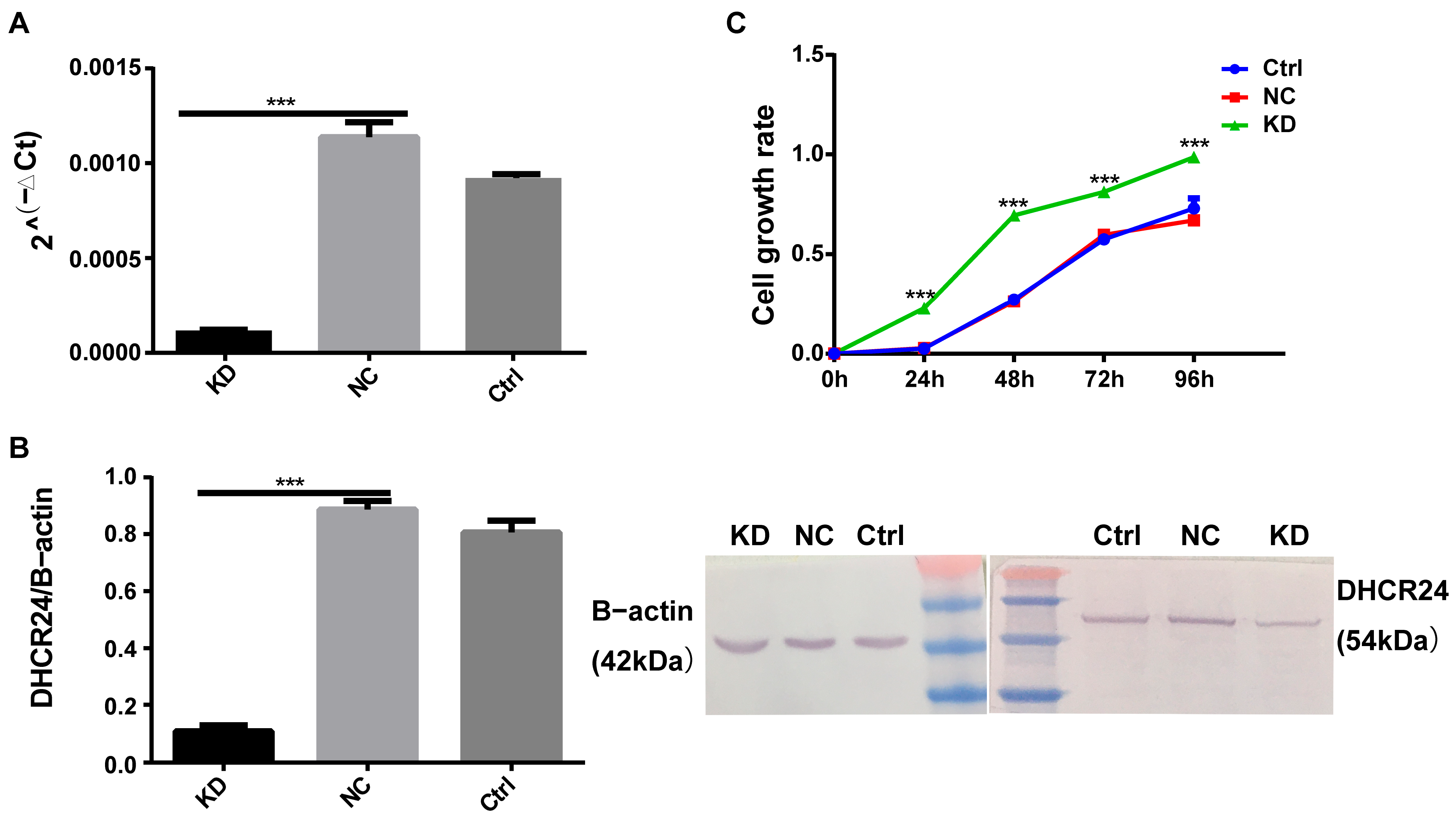

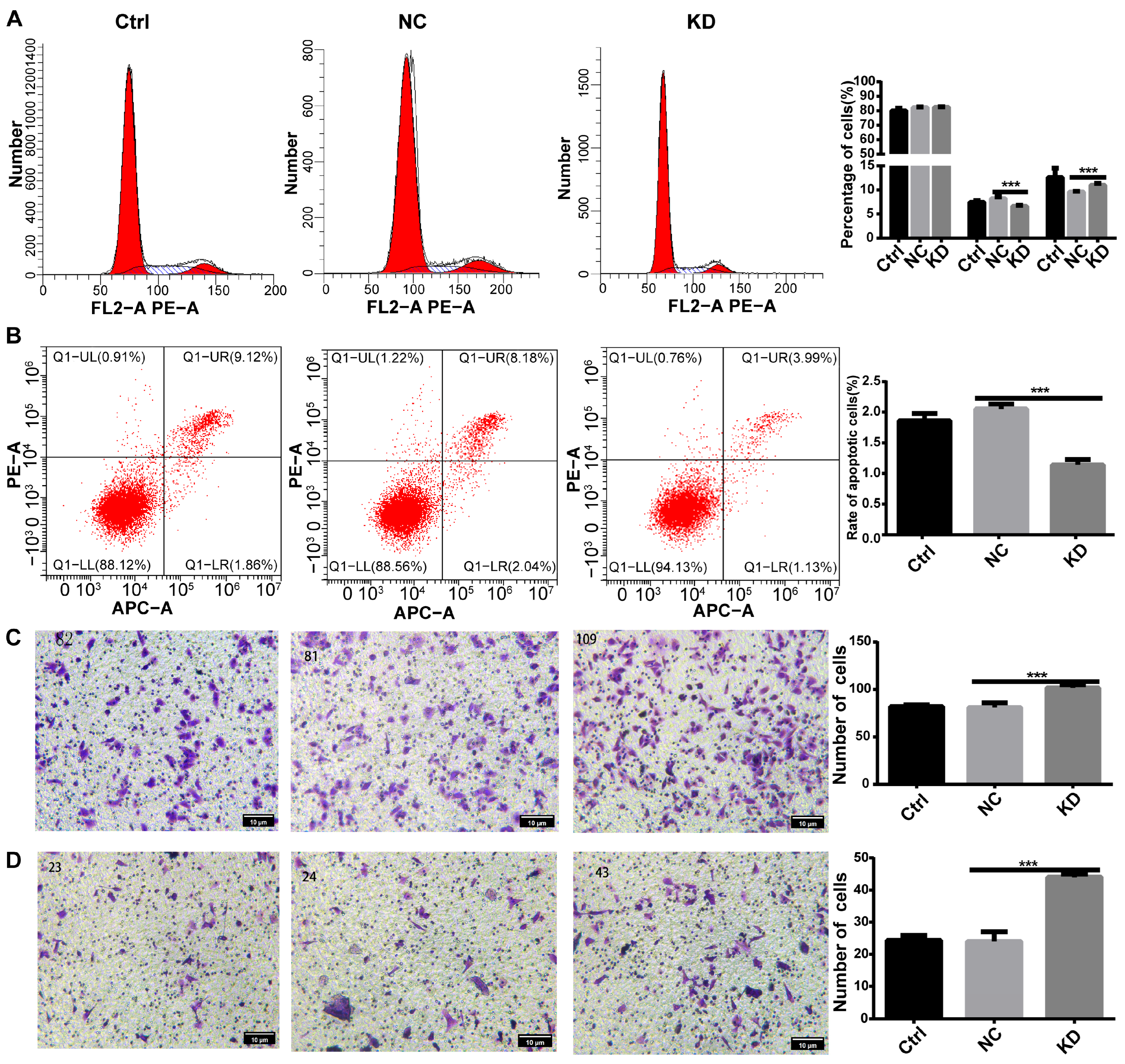

3.2. DHCR24 Knockdown Promotes Oncogenic Phenotypes in BC Cells

3.2.1. Expression Profiling Informs Experimental Selection

3.2.2. DHCR24 Knockdown Promotes Malignant Phenotypes in MCF7 Cells

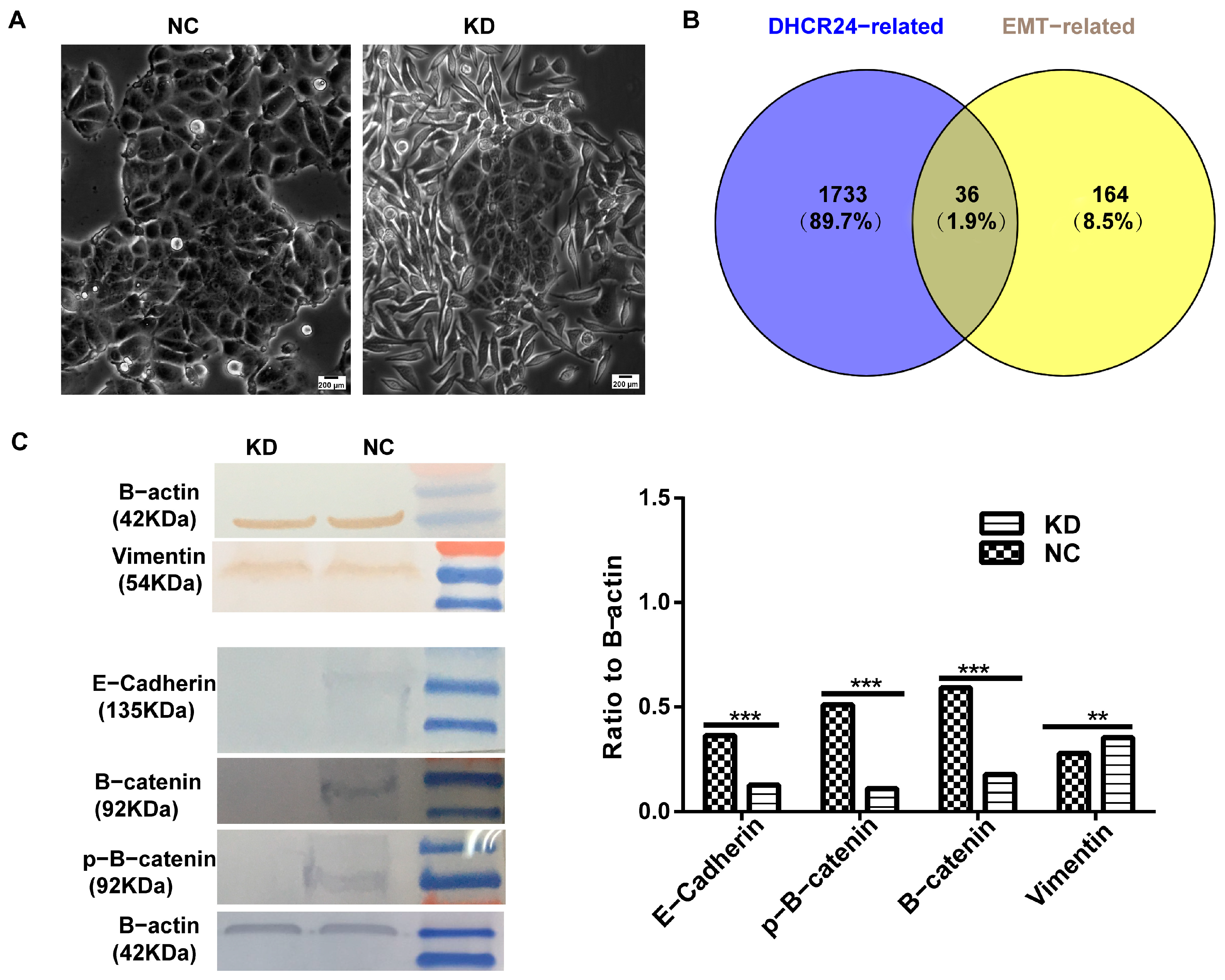

3.2.3. DHCR24 Knockdown Induces a Partial EMT Phenotype

3.3. Multi-Omics Analyses Implicate DHCR24 in Tumor Microenvironment Remodeling and Transcriptional Networks

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BC | Breast cancer |

| IHC | Immunohistochemical |

| PPI | Protein–protein interaction |

| IVW | Inverse-variance weighted |

| EMT | Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition, |

| MR | Mendelian randomization |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association study |

| GSEA | Gene set enrichment analysis |

| LD | Linkage disequilibrium |

References

- Kim, J.; Harper, A.; McCormack, V.; Sung, H.; Houssami, N.; Morgan, E.; Mutebi, M.; Garvey, G.; Soerjomataram, I.; Fidler-Benaoudia, M.M. Global patterns and trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality across 185 countries. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzaman, K.; Karami, J.; Zarei, Z.; Hosseinzadeh, A.; Kazemi, M.H.; Moradi-Kalbolandi, S.; Safari, E.; Farahmand, L. Breast cancer: Biology, biomarkers, and treatments. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 84, 106535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, K.; Song, M.; Ji, Y.; Zang, F.; Lou, L.; Rao, K.; et al. Integrated multi-omics profiling to dissect the spatiotemporal evolution of metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 135–156.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Wang, A.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, P.; Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Gao, J.; Wang, X.; Shu, L.; Lu, J.; et al. Spatially resolved multi-omics highlights cell-specific metabolic remodeling and interactions in gastric cancer. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; Song, B.-L.; Xu, C. Cholesterol metabolism in cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Chen, S.; Bai, X.; Liao, M.; Qiu, Y.; Zheng, L.-L.; Yu, H. Targeting cholesterol metabolism in Cancer: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic implications. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 218, 115907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, I.; Gianfanti, F.; Desbats, M.A.; Orso, G.; Berretta, M.; Prayer-Galetti, T.; Ragazzi, E.; Cocetta, V. Cholesterol Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer and Its Pharmacological Modulation as Therapeutic Strategy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 682911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, F.; Mader, S.; Philip, A. Cholesterol as an Endogenous Ligand of ERRα Promotes ERRα-Mediated Cellular Proliferation and Metabolic Target Gene Expression in Breast Cancer Cells. Cells 2020, 9, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ortiz, A.; Galindo-Hernández, O.; Hernández-Acevedo, G.N.; Hurtado-Ureta, G.; García-González, V. Impact of cholesterol-pathways on breast cancer development, a metabolic landscape. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 4307–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, C.; Goupille, C.; Vigor, C.; Durand, T.; Guéraud, F.; Silvente-Poirot, S.; Poirot, M.; Frank, P.G. Is cholesterol a risk factor for breast cancer incidence and outcome? J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 232, 106346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Wang, Z. DHCR24 in Tumor Diagnosis and Treatment: A Comprehensive Review. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 23, 15330338241259780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Meng, F.; Yang, M.; Chen, Y.; Guo, X.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Feng, C.; et al. A novel SRSF3 inhibitor, SFI003, exerts anticancer activity against colorectal cancer by modulating the SRSF3/DHCR24/ROS axis. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Nie, K.; Cheng, S.; Chen, Z.; Wang, W.; Wei, W.; Jiang, D.; Peng, Z.; Ren, Y.; et al. Oncogenic role of the SOX9-DHCR24-cholesterol biosynthesis axis in IGH-BCL2+ diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Blood 2022, 139, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; He, Y.; Xin, H. GDF15 promotes the resistance of epithelial ovarian cancer cells to gemcitabine via DHCR24-mediated cholesterol metabolism to elevate ABCB1 and ABCC1 levels in lipid rafts. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2025, 15, 452–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Cao, J.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liu, M.; He, L.; Wu, G.; Li, H.; et al. 24-Dehydrocholesterol reductase promotes the growth of breast cancer stem-like cells through the Hedgehog pathway. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 3653–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Mai, M.; Yao, K.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Guo, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qurban, A.; et al. The role of DHCR24 in the pathogenesis of AD: Re-cognition of the relationship between cholesterol and AD pathogenesis. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2022, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuehnle, K.; Crameri, A.; Kälin, R.E.; Luciani, P.; Benvenuti, S.; Peri, A.; Ratti, F.; Rodolfo, M.; Kulic, L.; Heppner, F.L.; et al. Prosurvival effect of DHCR24/Seladin-1 in acute and chronic responses to oxidative stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsworth, B.; Lyon, M.; Alexander, T.; Liu, Y.; Matthews, P.; Hallett, J.; Bates, P.; Palmer, T.; Haberland, V.; Smith, G.D.; et al. The MRC IEU OpenGWAS data infrastructure. bioRxiv 2020. bioRxiv:2020.08.10.244293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safran, M.; Rosen, N.; Twik, M.; BarShir, R.; Stein, T.I.; Dahary, D.; Fishilevich, S.; Lancet, D. The GeneCards Suite. In Practical Guide to Life Science Databases; Abugessaisa, I., Kasukawa, T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2021; pp. 27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Li, C.; Kang, B.; Gao, G.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z. GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W98–W102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Győrffy, B. Survival analysis across the entire transcriptome identifies biomarkers with the highest prognostic power in breast cancer. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 4101–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arafeh, R.; Shibue, T.; Dempster, J.M.; Hahn, W.C.; Vazquez, F. The present and future of the Cancer Dependency Map. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2025, 25, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhao, G.; Lu, Y.; Zuo, S.; Duan, D.; Luo, X.; Zhao, H.; Li, J.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, Q.; et al. TIMER3: An enhanced resource for tumor immune analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, W534–W541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; et al. The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustin, S.A.; Ruijter, J.M.; van den Hoff, M.J.B.; Kubista, M.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; Tran, N.; Rödiger, S.; Untergasser, A.; Mueller, R.; et al. MIQE 2.0: Revision of the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments Guidelines. Clin. Chem. 2025, 71, 634–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Lyon, D.; Junge, A.; Wyder, S.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Doncheva, N.T.; Morris, J.H.; Bork, P.; et al. STRING v11: Protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D607–D613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasaikar, S.V.; Deshmukh, A.P.; den Hollander, P.; Addanki, S.; Kuburich, N.A.; Kudaravalli, S.; Joseph, R.; Chang, J.T.; Soundararajan, R.; Mani, S.A. EMTome: A resource for pan-cancer analysis of epithelial-mesenchymal transition genes and signatures. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Hoyo, A.; Xiong, K.; Marczyk, M.; García-Millán, R.; Wolf, D.; Huppert, L.; Nanda, R.; Yau, C.; Hirst, G.; Veer, L.; et al. Correlation of hormone receptor positive HER2-negative/MammaPrint high-2 breast cancer with triple negative breast cancer: Results from gene expression data from the ISPY2 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, E.; Glymour, M.M.; Holmes, M.V.; Kang, H.; Morrison, J.; Munafò, M.R.; Palmer, T.; Schooling, C.M.; Wallace, C.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Mendelian randomization. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, K.; Shahmoradgoli, M.; Martínez, E.; Vegesna, R.; Kim, H.; Torres-Garcia, W.; Treviño, V.; Shen, H.; Laird, P.W.; Levine, D.A.; et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Gu, S.; Pan, D.; Fu, J.; Sahu, A.; Hu, X.; Li, Z.; Traugh, N.; Bu, X.; Li, B.; et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1550–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Bi, E.; Lu, Y.; Su, P.; Huang, C.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Yang, M.; Kalady, M.F.; Qian, J.; et al. Cholesterol Induces CD8+ T Cell Exhaustion in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 143–156.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Yan, W.; Kong, L.; Zuo, S.; Wu, J.; Zhu, C.; Huang, H.; He, B.; Dong, J.; Wei, J. Oncolytic viruses engineered to enforce cholesterol efflux restore tumor-associated macrophage phagocytosis and anti-tumor immunity in glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendre, S.; Krawczyńska, N.; Bhogale, S.; Weisser, E.; Han, S.; Hajyousif, B.; Singh, A.; Kc, R.; Wang, Y.; Schane, C.; et al. The Loss of Cholesterol Efflux Pump ABCA1 Skews Macrophages Towards a Pro-tumor Phenotype and Facilitates Breast Cancer Progression. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2024, 12, A048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altea-Manzano, P.; Decker-Farrell, A.; Janowitz, T.; Erez, A. Metabolic interplays between the tumour and the host shape the tumour macroenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2025, 25, 274–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elia, I.; Haigis, M.C. Metabolites and the tumour microenvironment: From cellular mechanisms to systemic metabolism. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafner, A.; Bulyk, M.L.; Jambhekar, A.; Lahav, G. The multiple mechanisms that regulate p53 activity and cell fate. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vousden, K.H.; Prives, C. Blinded by the Light: The Growing Complexity of p53. Cell 2009, 137, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clendening, J.W.; Penn, L.Z. Targeting tumor cell metabolism with statins. Oncogene 2012, 31, 4967–4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgquist, S.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Ahern, T.P.; Garber, J.E.; Colleoni, M.; Láng, I.; Debled, M.; Ejlertsen, B.; von Moos, R.; Smith, I.; et al. Cholesterol, Cholesterol-Lowering Medication Use, and Breast Cancer Outcome in the BIG 1-98 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Bermudez, J.; Baudrier, L.; Bayraktar, E.C.; Shen, Y.; La, K.; Guarecuco, R.; Yucel, B.; Fiore, D.; Tavora, B.; Freinkman, E.; et al. Squalene accumulation in cholesterol auxotrophic lymphomas prevents oxidative cell death. Nature 2019, 567, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Groups | Clinicopathological Parameters | Counts | DHCR24 | χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | |||||

| Age | ≥60 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 1 b |

| <60 | 47 | 18 | 29 | |||

| ER | Negative | 20 | 8 | 12 | 0.095 | 0.758 a |

| Positive | 39 | 14 | 25 | |||

| PR | Negative | 32 | 16 | 16 | 4.832 | 0.028 a |

| Positive | 27 | 6 | 21 | |||

| HER-2 | Negative | 42 | 20 | 22 | 5.208 | 0.022 b |

| Positive | 17 | 2 | 15 | |||

| Subtype | TNBC | 9 | 7 | 2 | 5.542 | 0.019 b |

| No-TNBC | 50 | 15 | 35 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, M.; Hu, J.; Pu, L.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, J.; Deng, S.; Liu, C. Multi-Omics Integration Identifies the Cholesterol Metabolic Enzyme DHCR24 as a Key Driver in Breast Cancer. Biology 2026, 15, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010040

Xu M, Hu J, Pu L, Liu J, Yang Y, Li Q, Chen J, Deng S, Liu C. Multi-Omics Integration Identifies the Cholesterol Metabolic Enzyme DHCR24 as a Key Driver in Breast Cancer. Biology. 2026; 15(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Mingfei, Jinghua Hu, Lulan Pu, Jiayou Liu, Yanhong Yang, Qianqian Li, Jingwen Chen, Shishan Deng, and Chaoyue Liu. 2026. "Multi-Omics Integration Identifies the Cholesterol Metabolic Enzyme DHCR24 as a Key Driver in Breast Cancer" Biology 15, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010040

APA StyleXu, M., Hu, J., Pu, L., Liu, J., Yang, Y., Li, Q., Chen, J., Deng, S., & Liu, C. (2026). Multi-Omics Integration Identifies the Cholesterol Metabolic Enzyme DHCR24 as a Key Driver in Breast Cancer. Biology, 15(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010040