The Coexistence of Bicellular and Tricellular Pollen Might Be the Third Type of Pollen Cell Number: Evidence from Annonaceae

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

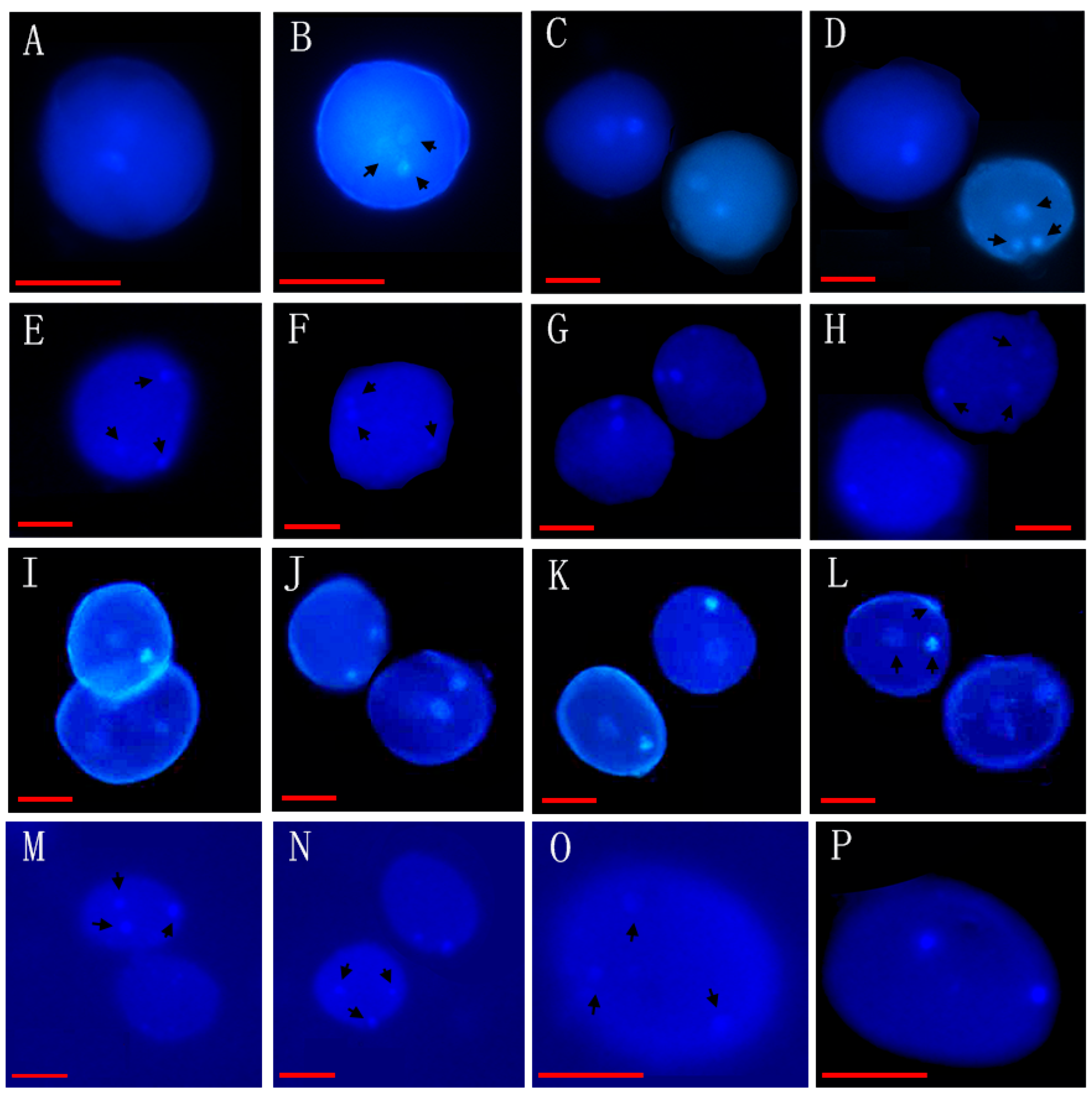

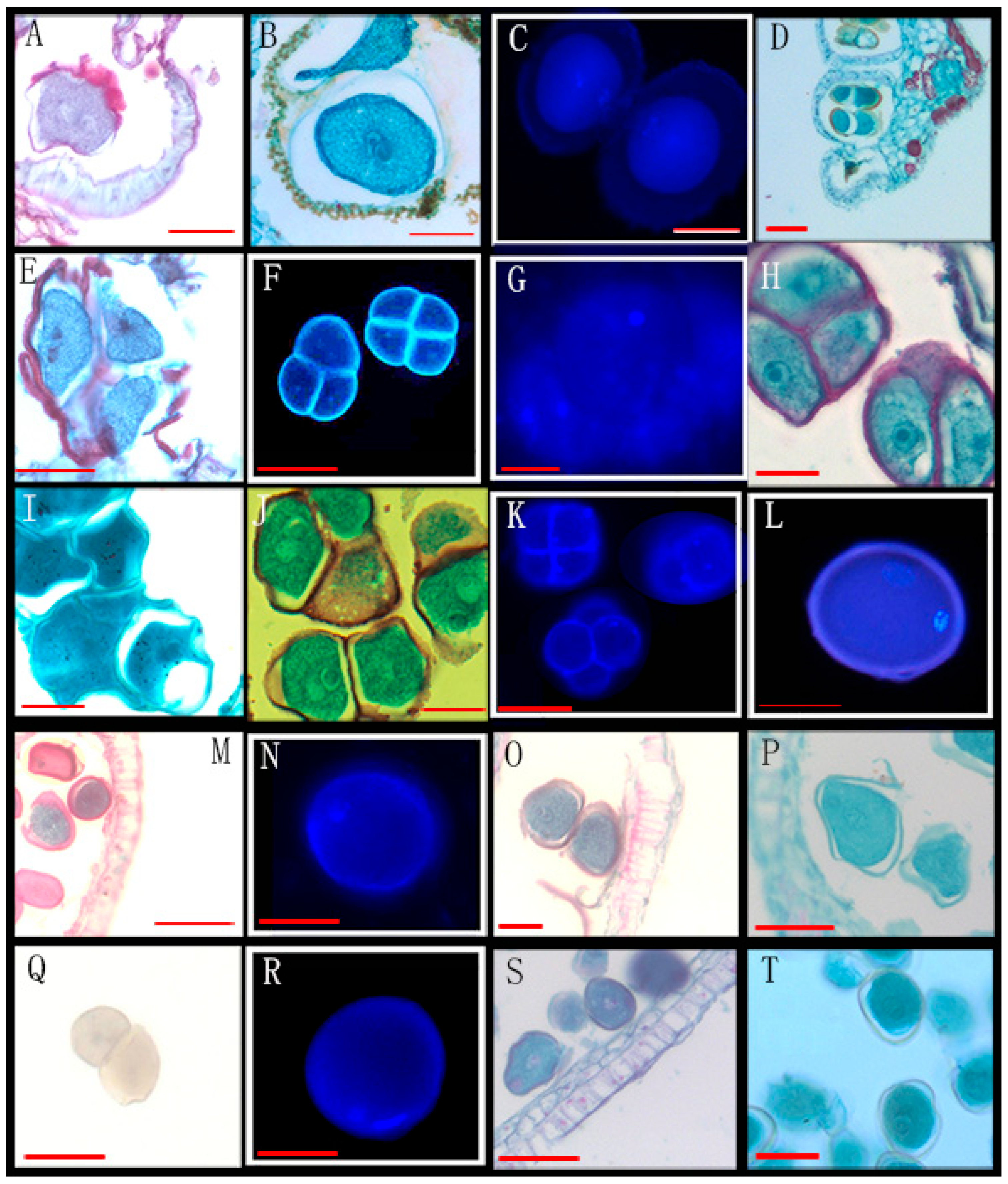

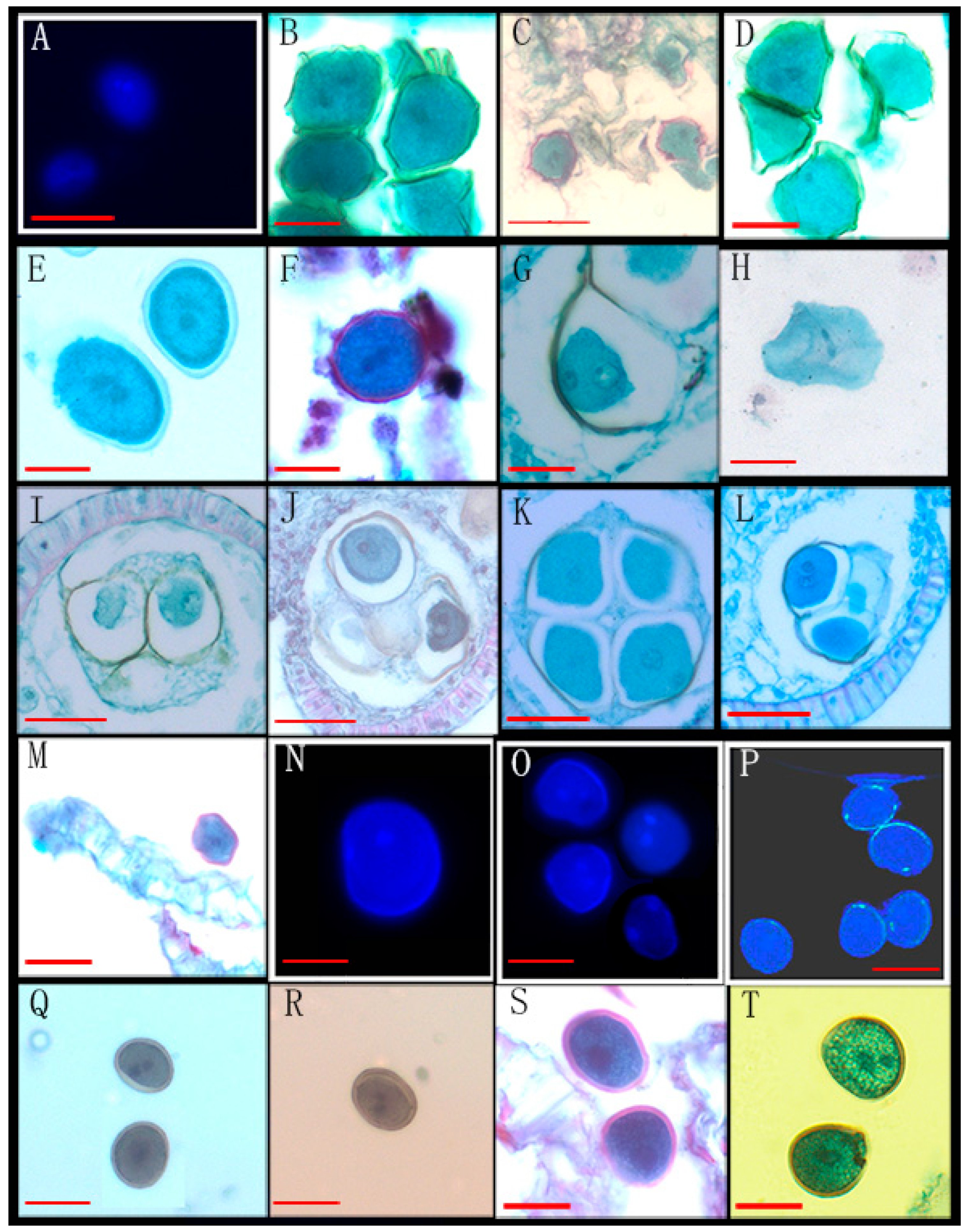

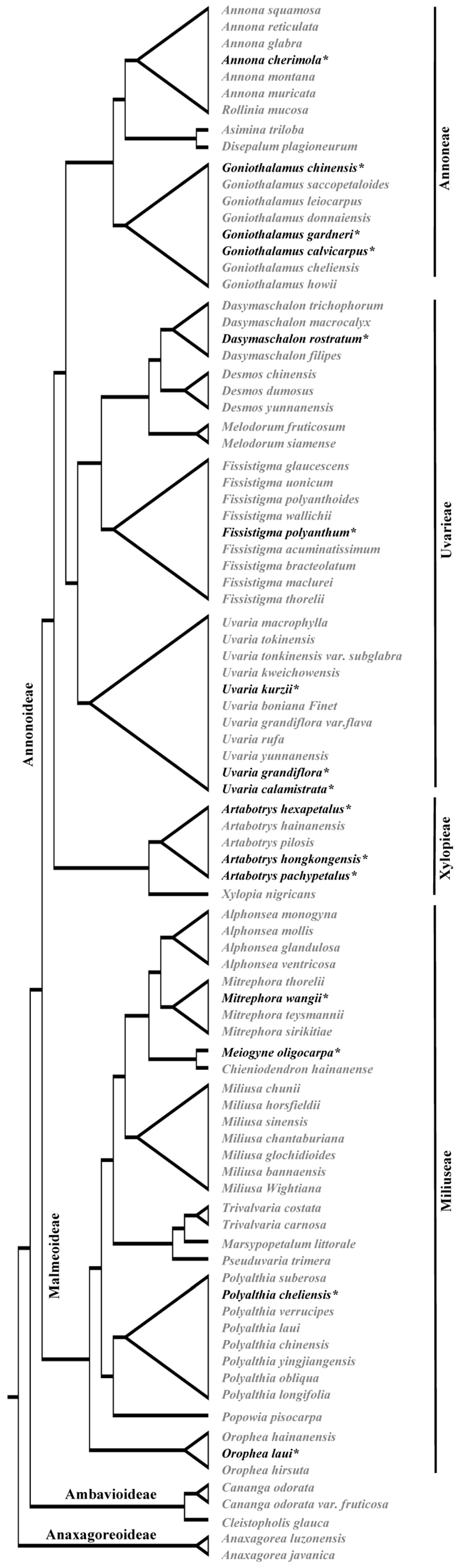

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. The Coexistence of Bicellular and Tricellular Pollen May Be More Prevalent in Angiosperms than We Thought

4.2. Is the Coexistence of Bicellular and Tricellular Pollen a Special Case or the Third Type?

4.3. Which Is Primitive and How It Evolved?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Williams, J.H.; Taylor, M.L.; O’Meara, B.C. Repeated evolution of tricellular (and bicellular) pollen. Am. J. Bot. 2014, 101, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurhoff, P.N. Die Zytologie der Blütenpfl Anzen; Enke: Stuttgart, Germany, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Brewbaker, J.L. Distribution and phylogenetic significance of bicellular and tricellular pollen grains in angiosperms. Am. J. Bot. 1967, 54, 1069–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, G.L.; Rupert, E.A. Phylogenetic significance of pollen nuclear number in Euphorbiaceae. Evolution 1973, 27, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayum, M.H. Phylogenetic implications of pollen nuclear number in the Araceae. Plant Syst. Evol. 1986, 151, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lora, J.; Herrero, M.; Hormaza, J.I. The coexistence of bicellular and tricellular pollen in Annona cherimola (Annonaceae): Implications for pollen evolution. Am. J. Bot. 2009, 96, 802–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.X.; Gornall, R.J. Systematic significance of pollen nucleus number in the genus Saxifraga (Saxifragaceae). Plant Syst. Evol. 2011, 295, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, R.; Dong, X.; Ding, Y. The development of flowering bud differentiation and male gametophyte of Bambusa multiplex. J. Nanjing For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 39, 51–56. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gan, Y.Y.; Xu, F.X. The coexistence of bicellular and tricellular pollen. Grana 2018, 58, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; He, M. Megasporogenesis, microsporogenesis and development of male anda female gametophytes of Adonis amurensis Regel et Radde. J. Northest For. Univ. 2017, 45, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, M.Y.; Lin, S.Y.; Yao, W.J.; Ding, Y.L. Inflorescence architecture of male and female gametophytes of Sasaella kogasensis ‘Aureostriatus’. J. Anhui Agric. Univ. 2021, 48, 9–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.Q.; Guo, C.C.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Wu, Z.C.; Yang, G.Y.; Yu, F.; Liu, H.W. Sporogenesis and gametogenesis of Pseudosasa viridula. Guihaia 2022, 42, 143–151. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, H. Cyto-embryological analysis of wild kentucky bluegrass germplasm in Gansu Province, China. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.D.; Zhou, L.; Wang, S.G. Floral morphology and development of female and male gametophytes of Bambusa textilis. For. Res. 2024, 37, 150–158. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Nie, T.; Wu, Q.; Jin, L.; Wan, X.; Yin, Z. The basic characteristics of stamen morphogenesis and development in Michelia figo. J. Nanjing For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 48, 34–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.M.; Sun, L.F.; Feng, Y.; Lian, C.; Ran, H.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Q. Observation on anther development of Phyllostachys edulis. Guihaia 2016, 36, 231–235. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chawasku, T.; Kessler, P.J.A.; van der Ham, R.W.J.M. A taxonomic revision and pollen morphology of the genus Dendrokingstonia (Annonaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2012, 168, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, S.O.; Folorunso, A.E. Phenology and pollen studies of some species of Annonaceae in Nigeria. IFE J. Sci. 2014, 16, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, F.X. Pollen morphology of selected species from Annonaceae. Grana 2015, 54, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.Y.; Xu, F.X. Studies on pollen morphology of selected species of Annonaceae from Thailand. Grana 2017, 1, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Tang, C.C.; Thomas, D.C.; Couvreur, T.L.; Saunders, R.M. A mega-phylogeny of the Annonaceae: Taxonomic placement of five enigmatic genera and support for a new tribe, Phoenicantheae. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periasamy, K.; Swamy, B.G.L. Studies in the Annonaceae I. Microsporogenesis in Cananga odorata and Miliusa wightiana. Phytomorphology 1959, 9, 251–263. [Google Scholar]

- Periasamy, K.; Kandasamy, M.K. Development of the anther of Annona squamosa L. Ann. Bot. 1981, 48, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periasamy, K.; Thangavel, S. Anther development in Xylopia nigricans. Proc. Plant Sci. 1988, 98, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, C.H.; Fu, Y.L. Octad pollen formation in Cymbopetalum (Annonaceae): The binding mechanism. Plant Syst. Evol. 2007, 263, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lora, J.; Herrero, M.; Hormaza, J.I. Pollen performance, cell number, and physiological state in the early-divergent angiosperm Annona cherimola Mill (Annonaceae) are related to environmental conditions during the final stages of pollen development. Sex. Plant Reprod. 2012, 25, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Zeng, Q.W.; Liao, J.P.; Xu, F.X. Anatomy and ontogeny of unisexual flowers in dioecious Woonyoungia septentrionalis (Dandy) Law (Magnoliaceae). J. Syst. Evol. 2009, 47, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.J.; Wang, R.M.; Zhai, B.J.; Gong, F.F.; Hou, F.F.; Wang, J.Y.; Wu, J.; Xing, G.M.; Kang, X.P.; Li, S. Preliminary study on correlation between microspore development and bud length of Hemerocallis and anther culture. J. Shanxi Agric. Sci. 2021, 49, 170–174. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.Y.; Long, H.; Li, P. Studies on embryology of Conyza canadensis (L.) C ronq. J. Wuhan Bot. Res. 2009, 37, 233–241. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.Y.; Long, H.; Li, P. Genesis of microspore, megaspore and the development of male gametophyte, female gametophyte in Diphylleia sinensis. Guihaia 2010, 30, 36–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.Y.; Long, H.; Ting-Ting, Y.I.; Li, L.I. Microsporogenesis and the development of male gametopyte in Swertia bimaculata. Guihaia 2010, 30, 584–593. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.Y.; Long, H.; Yi, T.T.; Li, P. Genesis of microspore and the development of male gametophyte in Tripterospermum discoideum. Guihaia 2010, 30, 316–323. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sampsom, F.B. Studies on the Monimiaceae III. Gametophyte development of Laurelia novae-zelandiae A. Cunn. (subfamily Antherospermoideae). Aust. J. Bot. 1969, 17, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.O. A survey of the distribution of bicellular and tricellular pollen in the New Zealand flora. N. Z. J. Bot. 1975, 13, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Róis, A.S.; Teixeira, G.; Sharbel, T.F.; Fuchs, J.; Martins, S.; Espírito-Santo, D.; Caperta, A.D. Male fertility versus sterility, cytotype, and DNA quantitative variation in seed production in diploid and tetraploid sea lavenders (Limonium sp., Plumbaginaceae) reveal diversity in reproduction modes. Sex. Plant Reprod. 2012, 25, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.Y. Studies on the Reproductive Biology of Shibataea chinensis and Arundinaria simoniif Albostriatus. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China, 2009. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M. Studies on Comparative Embryology Between Coptis deltoidea C. Y. In Cheng et Hsiao and Coptis Chinensis Franch; Chengdu University of Tranditional Chinese Medicine: Chengdu, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dnyansagar, V.R.; Cooper, D.C. Development of the seed of Solanum phureja. Am. J. Bot. 1960, 47, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Gu, L.; Liu, J.X. Sporogenesis, gametogenesis and pollen morphology of Solanum japonense and S. septemlobum (Solanaceae). Arch. Biol. Sci. 2018, 70, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Xu, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.; Hu, B.Z. Anatomical studies on microsporogenesis and development of male gametophyte in pansy. J. Northeast Agric. Univ. 2014, 45, 60–65. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, M.H. Morphological and cytological studies of Calla palustris. Bot. Gaz. 1937, 98, 556–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, P.; Herrero, M.; Sauco, V.G. Pollen germination of cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.). In vivo characterization and optimization of in vitro germination. Sci. Hortic. 1999, 8, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schürhoff, P.N. Die Zytologie der Blütenpflanzen; Enke: Stuttgart, Germany, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.L. Botany; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schurhoff, P.N. Zytologische Untersuchungen in der Reihe Geraniales. Jahrb. Wiss. Bot. 1924, 63, 707–758. [Google Scholar]

- Schnarf, K. Vergleichende Embryologie der Angiospermen; Gebrlider Borntraeger: Berlin, Germany, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Schnarf, K. Studien iiber den Bau der Pollenkorner der Angiospermen. Planta 1937, 27, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnarf, K. Variation im Bau der Pollenkorner der Angiospennen. Tabulae Biol. 1939, 17, 72–89. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, G.L.; Rupert, E.; Koutnik, D. Systematic significance of pollen nuclear number in Euphorbiaceae, tribe Euphorbieae. Am. J. Bot. 1982, 69, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, D.D.; Quinn, C.R.; Brenner, E.D.; Owens, J.N. Male gameto-phyte development and evolution in extant gymnosperms. Int. Plant Dev. Biol. 2010, 4, 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Franchi, G.G.; Piotto, B.; Nepi, M.; Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M.; Pacini, E. Pollen and seed desiccation tolerance in relation to degree of developmental arrest, dispersal, and survival. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 5267–5281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini, E.; Dolferus, R. Pollen developmental arrest maintaining pollen fertility in a world with a changing climate. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.H.; Brown, C.D. Pollen has higher water content when dispersed in a tricellular state than in a bicellular state. Acta Bot. Bras. 2018, 32, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Taxon | Provenance a | Voucher | Figures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Desmos chinensis Lour. | SCBG | xx060308, 20081072, xx271155 | Figure 4A |

| 2 | Desmos dumosus (roxb.)saff. | XTBG | 00012542, C06009, 273677 | Figure 4B |

| 3 | Desmos yunnanensis (Hu) P. T. Li | XTBG | 275056, 258389 | Figure 4C |

| 4 | Dasymaschalon trichophorum Merr. | SCBG | 20011172, 19975026, 19970018 | Figure 4D |

| 5 | Dasymaschalon filipes (Ridl.) Ridl.Ban | XTBG | 1320030093, 0020220650 | Figure 4E |

| 6 | Dasymaschalon rostratum Merr. & Chun * | XTBG | 0020023226, 0020020479 | Figure 3I,J |

| 7 | Dasymaschalon macrocalyx Finet & Gagnep. | XTBG | 1320030078, 0020022105 | Figure 4F |

| 8 | Polyalthia suberosa (Roxburgh) Thwaites | SCBG | 20010982, 20070804, 20140665 | Figure 4G |

| 9 | Polyalthia cheliensis Hu * | XTBG | 0020081058, 0020100741 | Figure 3M–P |

| 10 | Polyalthia verrucipes C. Y. Wu ex P. T. Li | XTBG | 0020031897(2) | Figure 4H |

| 11 | Polyalthia laui Merrill | SCBG | xx240010, xx320026 | Figure 4I |

| 12 | Polyalthia chinensis S. K. Wu & P. T. Li | XTBG | 0020023088, 0020150274 | Figure 4J |

| 13 | Polyalthia yingjiangensis Y. H. Tan and B. Xue | XTBG | 0020021384(3) | Figure 4K |

| 14 | Polyalthia obliqua Hook.f. & Thomson | XTBG | 0020013801(3) | Figure 4L |

| 15 | Polyalthia longifolia (Sonn.) Thwaites | SCBG | xx271140, 20055086 | Figure 4M |

| 16 | Hubera cerasoides (Roxb.) Benth.et Hook.f.ex Bedd. | SCBG | 20031137(3) | Figure 4N |

| 17 | Annona squamosa Linn. | XTBG | 0020071074(3) | Figure 5A |

| 18 | Annona muricata Linnaeus | SCBG | 19940242, 20070500 | Figure 5B |

| 19 | Annona montana Macf | XTBG | 0019600558A, 2019940014 | Figure 5C |

| 20 | Annona reticulata L. | XTBG | 0320140001, 275081 | Figure 5D |

| 21 | Annona glabra Linn. | SCBG | xx080063, xx080276, xx080383 | Figure 5E |

| 22 | Annona cherimola Mill. * | XTBG | 1520060007(3) | Figure 2Q |

| 23 | Cananga odorata (Lamarck) J. D. Hooker & Thomson | SCBG | 20090663, 20140876, xx120033 | Figure 4O |

| 24 | Cananga odorata var. fruticosa (Craib) J.Sinclair | SCBG | 20040790(3) | Figure 4P |

| 25 | Mitrephora thorelii Pierre | SCBG | 20030719(3) | Figure 5F |

| 26 | Mitrephora wangii Hu * | XTBG | 0020022041, 256509, 0019780252 | Figure 3A–D |

| 27 | Mitrephora teysmannii Scheff | SCBG | 20042613(3) | Figure 5G,H |

| 28 | Mitrephora sirikitiae Weeras | XTBG | 3820130137(3) | Figure 5I |

| 29 | Pseuduvaria trimera (Craib) YCF Su & RMK. Saunders | XTBG | 0019880077, 274490, 3020020011 | Figure 5J,K |

| 30 | Alphonsea monogyna Merrill & Chun | SCBG | 20011014(3) | Figure 4Q |

| 31 | Alphonsea mollis Dunn | XTBG | 0020040356, 0020150149, 286072 | Figure 4R |

| 32 | Alphonsea glandulosa Y.H. Tan & B. Xue | XTBG | 0019750173(3) | Figure 4S |

| 33 | Alphonsea ventricosa (Roxb.) Hook.f.&Thomson | XTBG | 0019970165(3) | Figure 4T |

| 34 | Artabotrys hexapetalus (L. f.) Bhanda * | XTBG | 0020040193, 0020090146 | Figure 1I–L |

| 35 | Artabotrys hainanensis R. E. Fries | SCBG | 20012148(3) | Figure 5L |

| 36 | Artabotrys pilosis Merrill & Chun | SCBG | 00012542(3) | Figure 5M |

| 37 | Artabotrys hongkongensis Hance * | SCBG | 20011052(3) | Figure 1M–P |

| 38 | Artabotrys pachypetalus B.Xue & Junhao Chen * | SCBG | 00028772(3) | Figure 2A–D |

| 39 | Trivalvaria costata (J. D. Hooker & Thomson) I. M. Turner | SCBG | xx110217(3) | Figure 5N,O |

| 40 | Trivalvaria carnosa (Teijsm. & Binn.) Scheff | XTBG | 1320010126(3) | Figure 5P |

| 41 | Uvaria macrophylla Roxb | XTBG | 0020023255, 287484, 0020090148 | Figure 6A |

| 42 | Uvaria grandiflora Roxb * | XTBG | 3820021106(3) | Figure 1A–D |

| 43 | Uvaria calamistrata Hance * | XTBG | 0020201075(3) | Figure 2R,S |

| 44 | Uvaria tokinensis Finet et Gagnep | XTBG | 3820020732(3) | Figure 6B |

| 45 | Uvaria tonkinensis var. subglabra Melodorum | SCBG | 20030552(3) | Figure 6C |

| 46 | Uvaria kweichowensis P. T. Li | SCBG | 20031112(3) | Figure 6D |

| 47 | Uvaria kurzii (King) P. T. Li * | SCBG | 042778(3) | Figure 1E–H |

| 48 | Uvaria boniana Finet et Gagnep | SCBG | 00044133(3) | Figure 6H |

| 49 | Uvaria grandiflora var. flava (Teijsm. & Binn.) Scheff | XTBG | 3820130135(3) | Figure 6E |

| 50 | Uvaria rufa Bl | XTBG | 284407(3) | Figure 6F |

| 51 | Uvaria yunnanensis Hu | XTBG | 0020070685(3) | Figure 5Q |

| 52 | Marsypopetalum littorale (Bl.) B. Xue & R. M. K. | XTBG | 0020012213(3) | Figure 5R |

| 53 | Goniothalamus chinensis Merr. et Chun * | XTBG | 3020021381, 0020162454 | Figure 3Q–T |

| 54 | Goniothalamus calvicarpus Craib * | SCBG | 20042665, 284928, 275874 | Figure 2E–H |

| 55 | Goniothalamus gardneri Hook. f. et Thoms * | SCBG | 20113045(3) | Figure 2I–L |

| 56 | Goniothalamus saccopetaloides Y.H. Tan and Bin Yang | XTBG | 3020020407(2) | Figure 6G |

| 57 | Goniothalamus cheliensis Hu | XTBG | 3020050005, C30121, 274125 | Figure 6K |

| 58 | Goniothalamus leiocarpus (W. T. Wang) P. T. Li | XTBG | 0020013790(2) | Figure 6L |

| 59 | Goniothalamus howii Merrill & Chun | XTBG | 0020021240(2) | Figure 6I |

| 60 | Goniothalamus donnaiensis Finet et Gagnep | LMNR | AU072086 b | Figure 6J |

| 61 | Fissistigma wallichii (Hook. f. et Thoms.) Merr | XTBG | 0020070161, 0020100719 | Figure 6P |

| 62 | Fissistigma glaucescens (Hance) Merrill | SCBG | XX271312(2) | Figure 6O |

| 63 | Fissistigma polyanthum Hook. f. et Thoms * | SCBG | 20050538(2) | Figure 2M–P |

| 64 | Fissistigma polyanthoides (Aug. DC.) Merr. | XTBG | 0020011877, 275869, 275870 | Figure 6N |

| 65 | Fissistigma acuminatissimum Merrill | XTBG | 285650(2) | Figure 6M |

| 66 | Fissistigma bracteolatum Chatt | XTBG | 374189, 274189, 277352 | Figure 6Q |

| 67 | Fissistigma maclurei Merr | XTBG | 0020080638, 286008, 286009 | Figure 6R |

| 68 | Fissistigma uonicum (Dunn) Merr | NMNR | 0078738 b | Figure 6S |

| 69 | Fissistigma thorelii (Pierre ex Finet&Gagnep.) Merr | XTBG | 0020020480, 0020031109 | Figure 6T |

| 70 | Meiogyne oligocarpa B. Xue & Y. H. Tan * | XTBG | 0020013864(2) | Figure 3E–H |

| 71 | Chieniodendron hainanense (Merr.) Tsiang et P. T. Li | SCBG | 19980193(2) | Figure 5S |

| 72 | Cleistopholis glauca Pierre ex Engl. & Diels | XTBG | 3119800151(2) | Figure 5T |

| 73 | Orophea hainanensis Merr | SCBG | 20011196(3) | Figure 7A,B |

| 74 | Orophea laui Leonardía & Kessler * | XTBG | 275549, 287159 | Figure 3K,L |

| 75 | Orophea hirsuta King | SCBG | 20011196(2) | Figure 7C |

| 76 | Anaxagorea luzonensis A. Gray | DMNR | 1020170057(2) | Figure 7D |

| 77 | Anaxagorea javanica Blume | XTBG | 3820021060, 0020200920 | Figure 7E |

| 78 | Miliusa chunii W. T. Wan | XTBG | 0019970179(2) | Figure 7F |

| 79 | Miliusa horsfieldii (Bennett) Pierre | SCBG | 20051897(2) | Figure 7G |

| 80 | Miliusa sinensis Finet et Gagnep | SCBG | 011047(2) | Figure 7H,I |

| 81 | Miliusa chantaburiana Damthongdee & Chaowasku | XTBG | 0020210589(2) | Figure 7J |

| 82 | Miliusa glochidioides Hand.-Mazz. | SCBG | 20113642(2) | Figure 7K |

| 83 | Miliusa bannaensis X.L. Hou | XTBG | 0020060634(2) | Figure 7L |

| 84 | Melodorum fruticosum Lour | XTBG | 3820021019(2) | Figure 7M |

| 85 | Melodorum siamense (Scheff.) Bân | XTBG | 3820021101(2) | Figure 7N |

| 86 | Disepalum plagioneurum (Diels) D. M. Johnson | DMNR | 01187407 b | Figure 7P |

| 87 | Popowia pisocarpa (Bl.) Endl. in Walp. Rep | DMNR | 0079742 b | Figure 7R |

| 88 | Asimina triloba Dunal. | WBG | 20177223(2) | Figure 7O,Q |

| 89 | Rollinia mucosa (Jacquin) Baillon | SCBG | AU080617 b | Figure 7S |

| No. | Family | Taxon | % of Anthers with Both Types of Pollen | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Annonaceae | Uvaria grandiflora Roxb | 23.2% (±3%) | Present paper |

| 2 | Annonaceae | Uvaria kurzii (King) P. T. Li | 55.0% (±5%) | Present paper |

| 3 | Annonaceae | Uvaria calamistrata Hance | 33.3% (±5%) | Present paper |

| 4 | Annonaceae | Annona cherimola Mill | 53.0% (±3%) | Present paper; [6] |

| 5 | Annonaceae | Mitrephora wangii Hu | 33.3% (±5%) | Present paper |

| 6 | Annonaceae | Mitrephora maingayi Hook. f. et Thoms | 33.3% (±5%) | [9] |

| 7 | Annonaceae | Artabotrys hexapetalus (L. f.) Bhandar | 25.0% (±5%) | Present paper |

| 8 | Annonaceae | Artabotrys hongkongensis Hance | 55.6% (±5%) | Present paper |

| 9 | Annonaceae | Artabotrys pachypetalus B.Xue & Junhao | 50.0% (±3%) | Present paper |

| 10 | Annonaceae | Goniothalamus calvicarpus Craib | 54.5% (±5%) | Present paper |

| 11 | Annonaceae | Goniothalamus gardneri Hook. f. et Thoms | 52.5% (±3%) | Present paper |

| 12 | Annonaceae | Goniothalamus chinensis Merr. et Chun | 53.5% (±5%) | Present paper |

| 13 | Annonaceae | Fissistigma polyanthum Hook. f. et Thoms | 53.0% (±3%) | Present paper |

| 14 | Annonaceae | Dasymaschalon rostratum Merr. & Chun | 50.0% (±2%) | Present paper |

| 15 | Annonaceae | Meiogyne oligocarpa B. Xue & Y. H. Tan | 51.0% (±2%) | Present paper |

| 16 | Annonaceae | Orophea laui Leonardía & Kessler | 53.0% (±5%) | Present paper |

| 17 | Annonaceae | Polyalthia cheliensis Hu | 52.5% (±5%) | Present paper |

| 18 | Araceae | Calla palustris | —— | [5] |

| 19 | Araceae | Rhodospatha forgetii | —— | [5] |

| 20 | Araceae | Anubias afzelii | —— | [5] |

| 21 | Araceae | Dieffenbachia maculata | —— | [5] |

| 22 | Araceae | Xanthosoma pilosum | —— | [5] |

| 23 | Araceae | Chlorospatha castula | —— | [5] |

| 24 | Araceae | Alocasia cuprea | —— | [5] |

| 25 | Asphodelaceae | Hemerocallis sp. | —— | [28] |

| 26 | Asteraceae | Conyza canadensis (L.) C ronq | —— | [29] |

| 27 | Berberidaceae | Leontice incerta Pall. | —— | [13] |

| 28 | Berberidaceae | Diphylleia sinensis H. L. Li | —— | [30] |

| 29 | Euphorbiaceae | Beyeria leschenaultii | —— | [4] |

| 30 | Gentianaceae | Swertia bimaculata | —— | [31] |

| 31 | Gentianaceae | Tripterospermum chinense (Migo) Harry Sm. | —— | [32] |

| 32 | Lauraceae | Laurelia novae-zelandiae A. Cunn | —— | [33] |

| 33 | Lauraceae | Beilschmiedia tara | —— | [34] |

| 34 | Lauraceae | Beilschmiedia taw | —— | [34] |

| 35 | Magnoliaceae | Michelia figo (Lour.) Spreng. | —— | [15] |

| 36 | Plumbaginaceae | Limonium sp. | —— | [35] |

| 37 | Poaceae | Bambusa textilis | —— | [14] |

| 38 | Poaceae | Shibataea chinensis | —— | [36] |

| 39 | Poaceae | Arundinaria simonii f. albostriatus | —— | [36] |

| 40 | Poaceae | Pseudosasa viridula | —— | [12] |

| 41 | Poaceae | Menstruocalamus sichuanensis | —— | [36] |

| 42 | Poaceae | Bambusa multiplex | —— | [8] |

| 43 | Poaceae | Sasaella kogasensis ‘Aureostriatus’ | —— | [11] |

| 44 | Poaceae | Phyllostachys edulis (Carrière) J. Houzeau | —— | [16] |

| 45 | Ranunculaceae | Adonis amurensis Regel et Radde. | —— | [10] |

| 46 | Ranunculaceae | Coptis deltoidea C. Y. Cheng et Hsiao | —— | [37] |

| 47 | Saxifragaceae | Saxifraga pseudohirculus | —— | [7] |

| 48 | Saxifragaceae | Saxifraga caveana | —— | [7] |

| 49 | Solanaceae | Solanum phureja | —— | [38] |

| 50 | Solanaceae | Solanum japonense Nakai | —— | [39] |

| 51 | Solanaceae | Solanum septemlobum Bunge | —— | [39] |

| 52 | Violaceae | Viola tricolor L. | —— | [40] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xiao, C.; Ping, J. The Coexistence of Bicellular and Tricellular Pollen Might Be the Third Type of Pollen Cell Number: Evidence from Annonaceae. Biology 2025, 14, 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14050562

Gan Y, Zhang Q, Xiao C, Ping J. The Coexistence of Bicellular and Tricellular Pollen Might Be the Third Type of Pollen Cell Number: Evidence from Annonaceae. Biology. 2025; 14(5):562. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14050562

Chicago/Turabian StyleGan, Yangying, Qi Zhang, Chunfen Xiao, and Jingyao Ping. 2025. "The Coexistence of Bicellular and Tricellular Pollen Might Be the Third Type of Pollen Cell Number: Evidence from Annonaceae" Biology 14, no. 5: 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14050562

APA StyleGan, Y., Zhang, Q., Xiao, C., & Ping, J. (2025). The Coexistence of Bicellular and Tricellular Pollen Might Be the Third Type of Pollen Cell Number: Evidence from Annonaceae. Biology, 14(5), 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14050562