Genome-Wide Identification of PGRP Gene Family and Its Role in Dendrolimus kikuchii Immune Response Against Bacillus thuringiensis Infection

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Material, Bt Treatment, and Tissue Sampling

2.2. RNA Extraction, High-Throughput Sequencing, and Data Analysis

2.3. Identification of the PGRP Gene Family

2.4. Characterization of PGRP Genes

2.5. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.6. siRNA Interference and Functional Validation

3. Results

3.1. Genome-Wide Identification of PGRP Genes in Dendrolimus kikuchii

3.2. Characterization of Dendrolimus kikuchii PGRPs

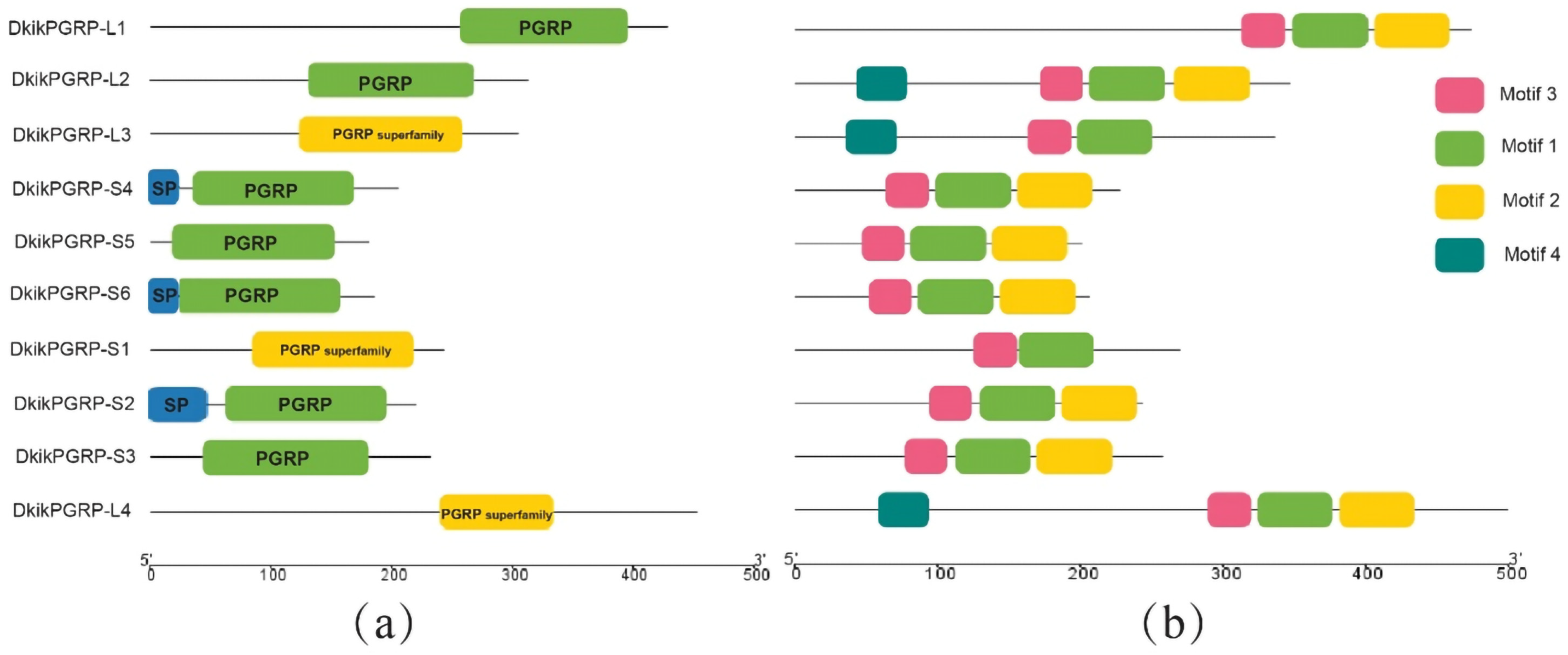

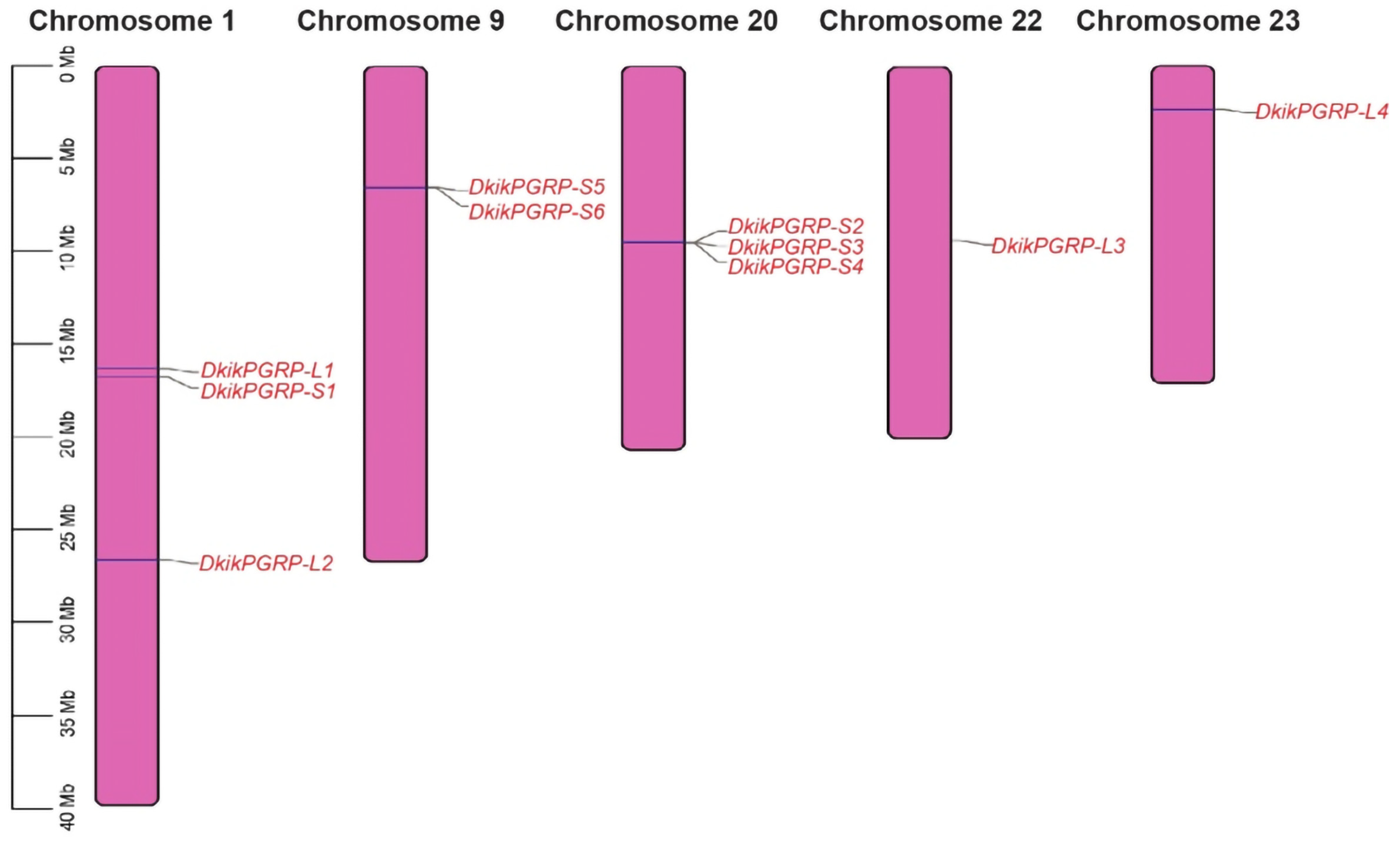

3.3. Motif Patterns, Conserved Domains, and Chromosomal Localization of PGRPs

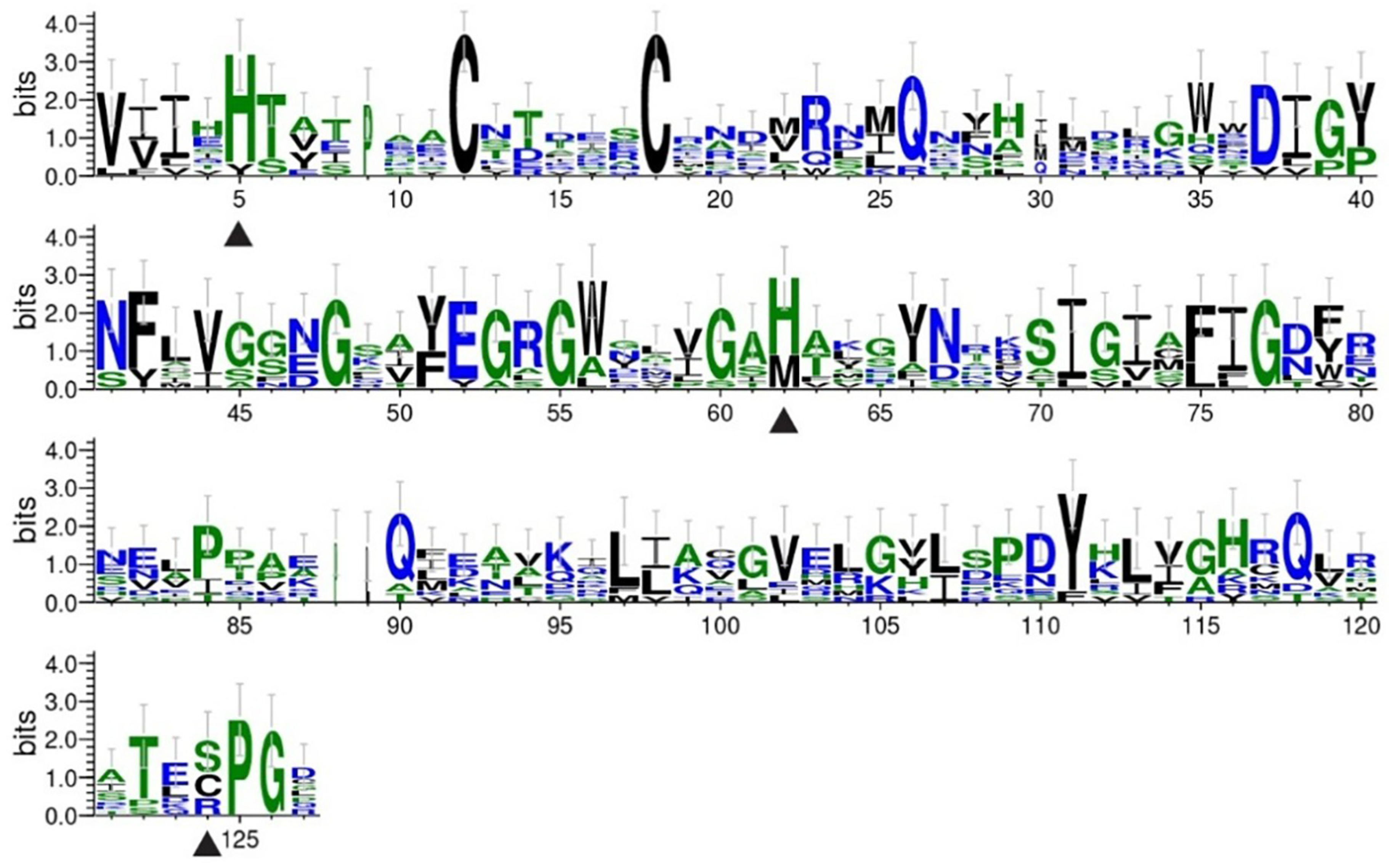

3.4. Domain Analysis of PGRPs

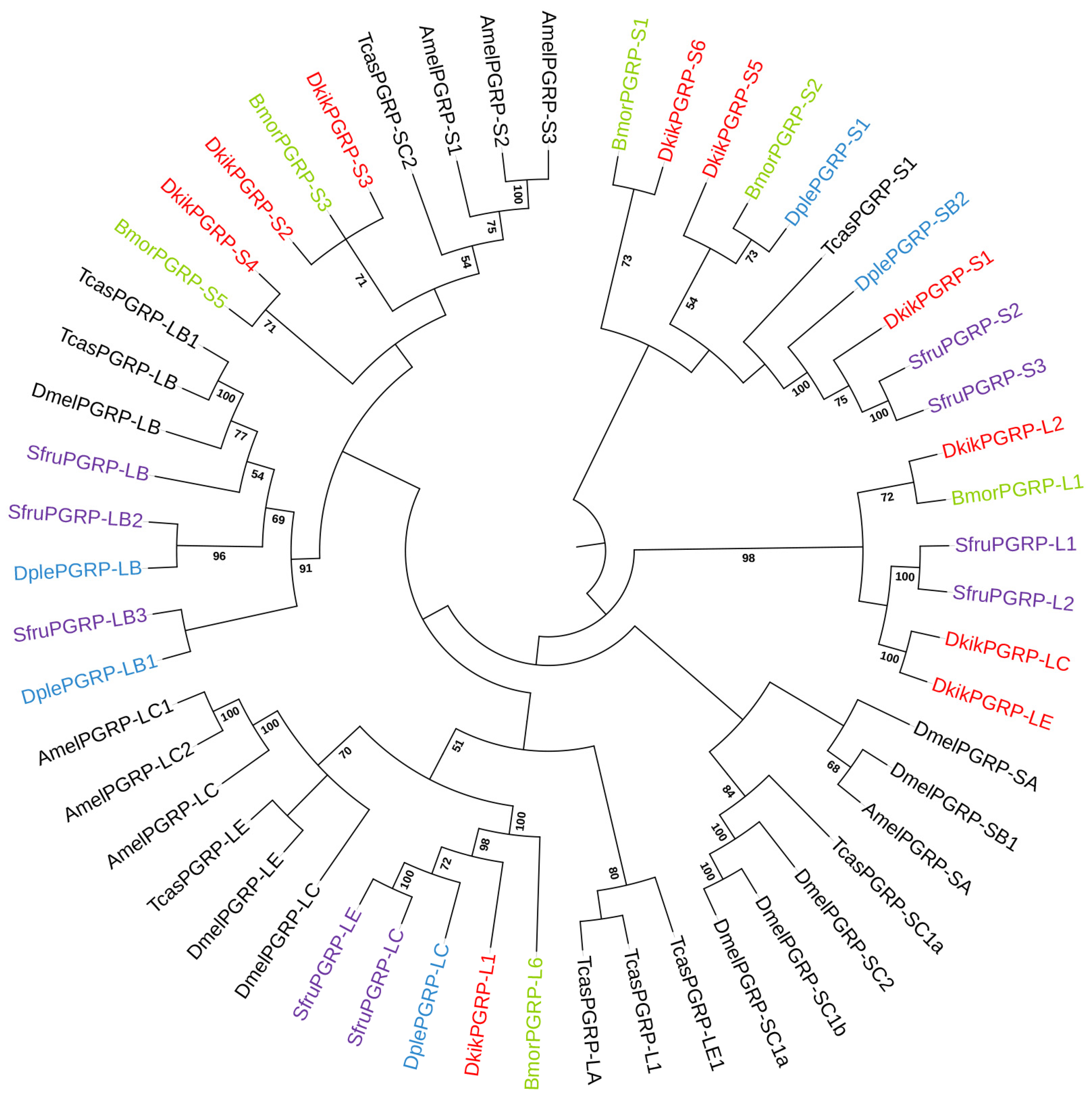

3.5. Phylogenetic Analysis of the PGRP Family

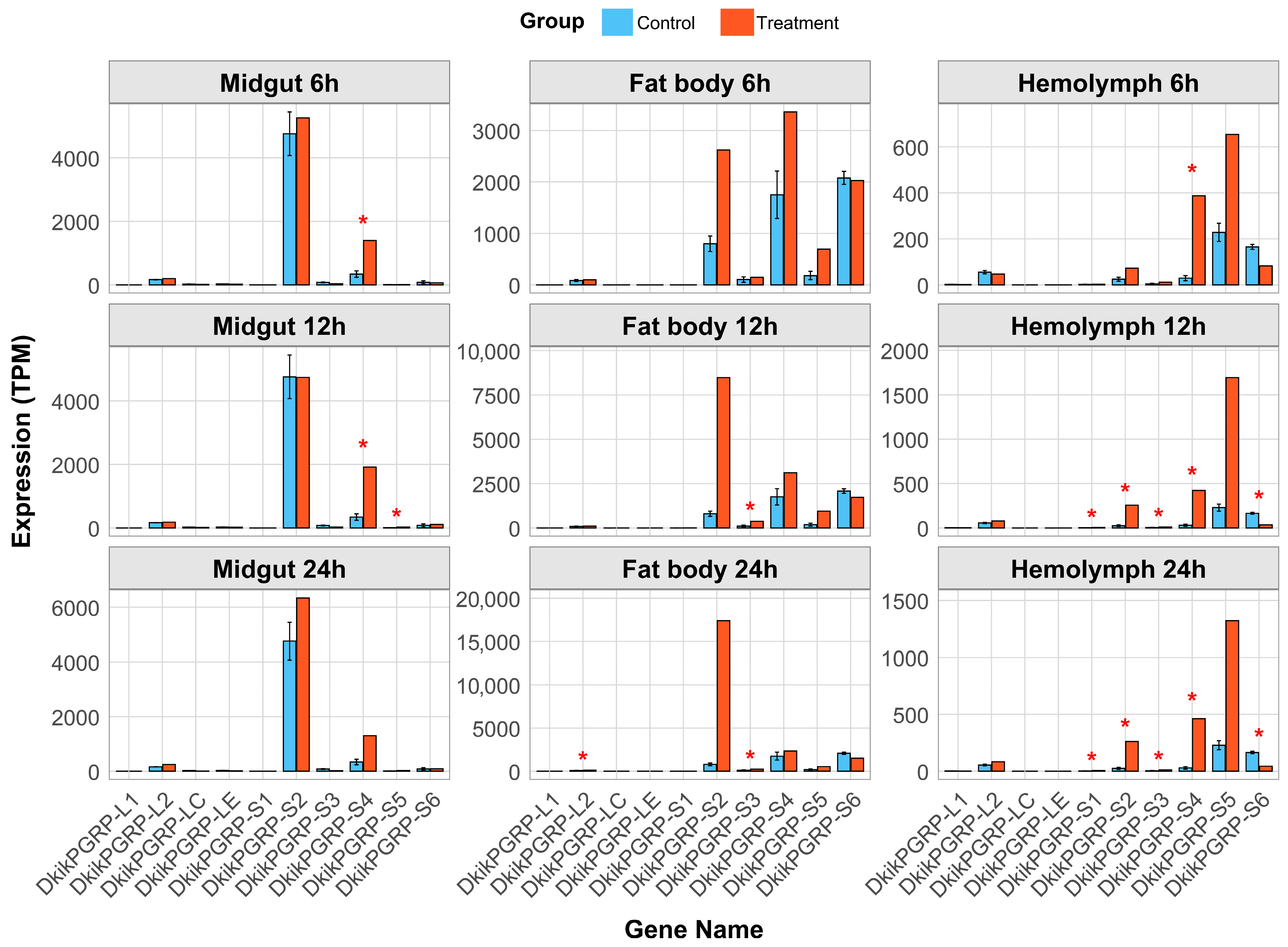

3.6. Tissue-Specific Transcriptional Expression of PGRP Genes Under Bt Infection

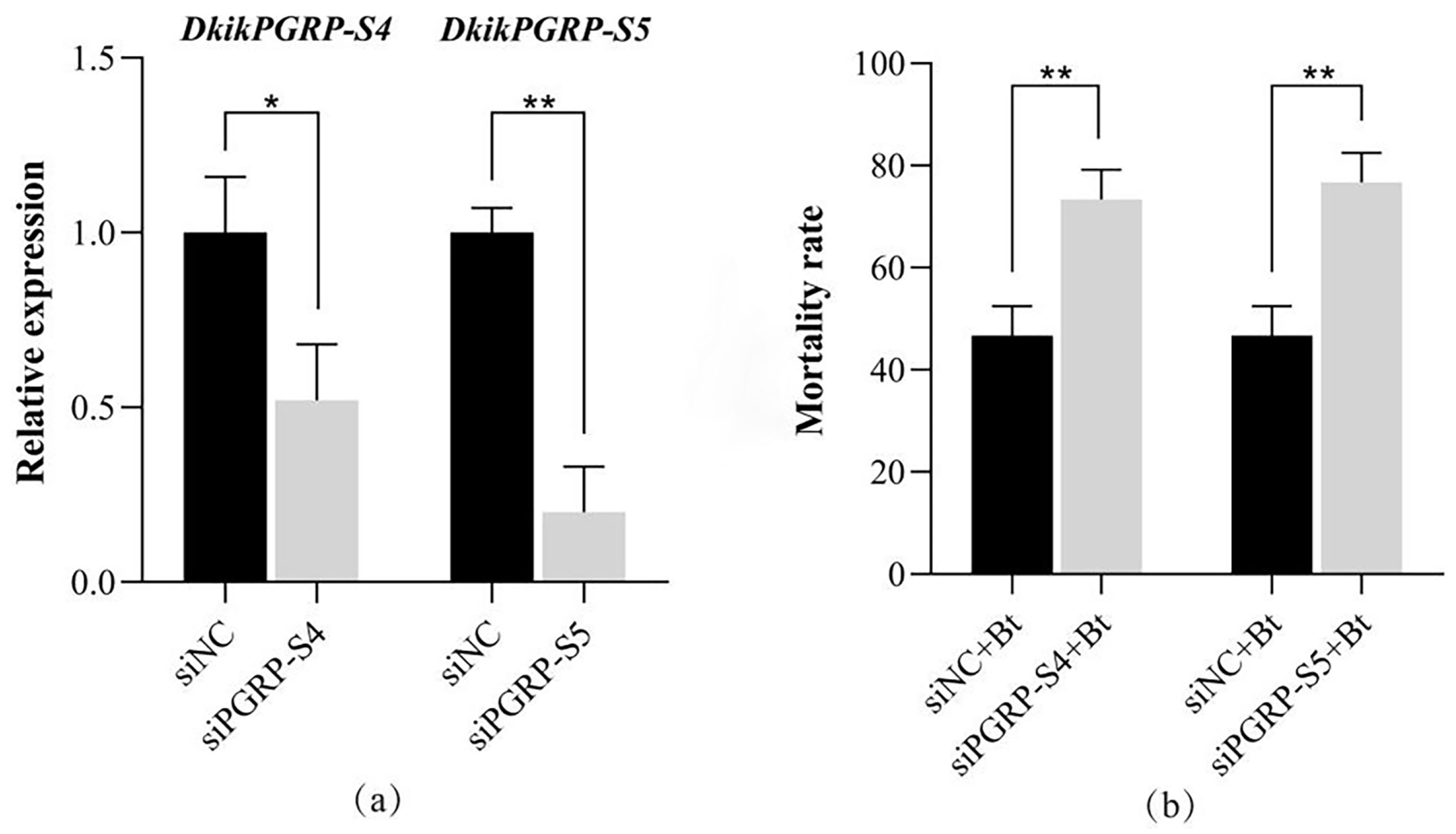

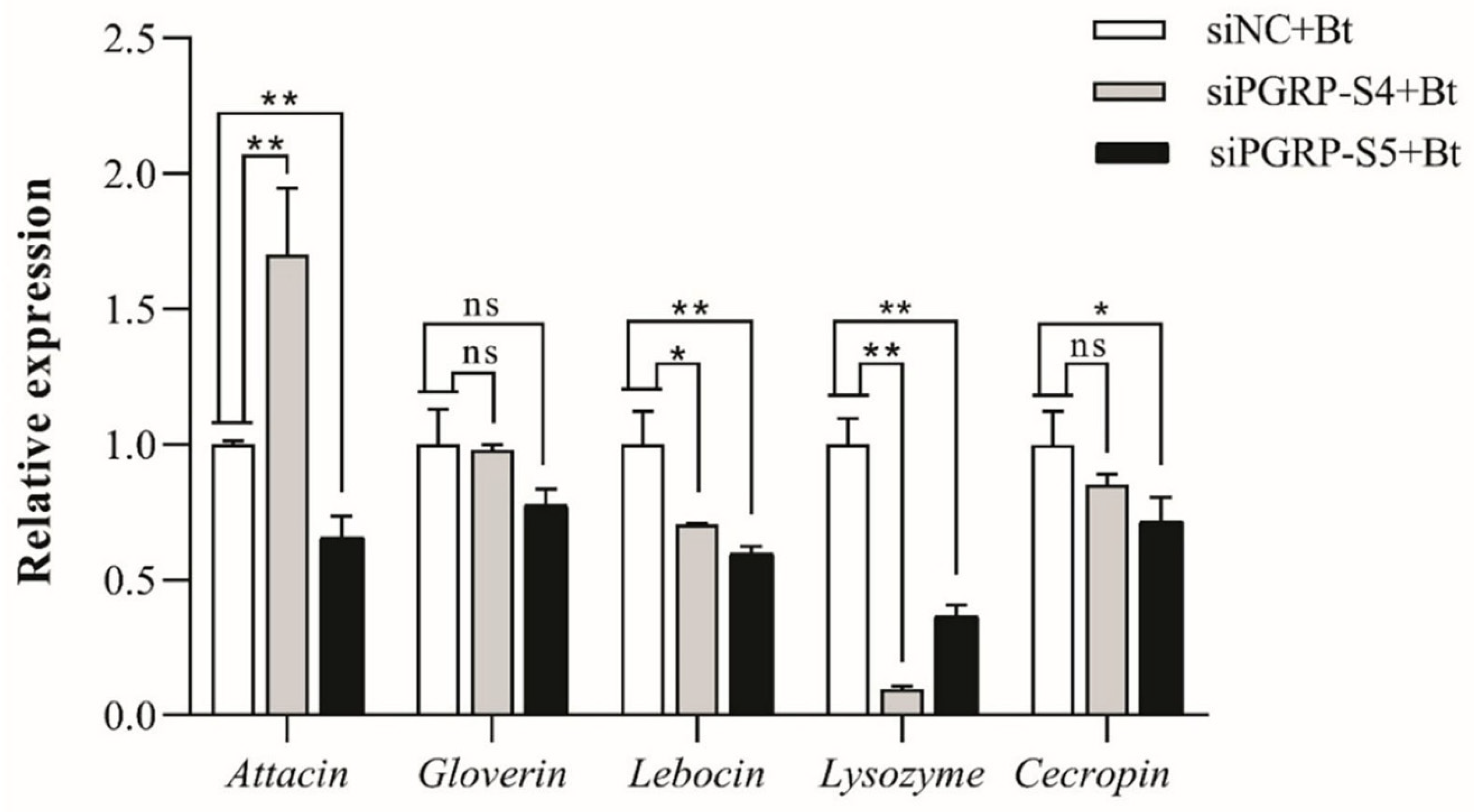

3.7. Functional Analysis of DkikPGRP-S4 and DkikPGRP-S5 in Immune Regulation

3.7.1. Effects of siRNA on Gene Expression and Bt Virulence

3.7.2. Regulation of Downstream AMP Gene Expression by DkikPGRP-S4 and DkikPGRP-S5

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PGRP | Peptidoglycan recognition proteins |

| PRRS | Pattern Recognition Receptors |

| PGN | Peptidoglycan |

| PPO | Prophenoloxidase |

| Bt | Bacillus thuringiensis |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| AMP | Antimicrobial Peptide |

| siNC | siRNA Negative Control |

| CDS | Coding Sequence |

| CDD | Conserved Domain Database |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| siRNA | Small Interfering RNA |

| qRT-PCR | Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR |

| 5′-RACE | Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends |

References

- Zhang, Z.; Kong, J.; De Mandal, S.; Li, S.; Zheng, Z.; Jin, F.; Xu, X. An Immune-Responsive PGRP-S1 Regulates the Expression of Antibacterial Peptide Genes in Diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L.). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 142, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H.; Kinoshita, K.; Ashida, M. Purification of a Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein from Hemolymph of the Silkworm, Bombyx mori. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 13854–13860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ren, M.; Liu, X.; Xia, H.; Chen, K. Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins in Insect Immunity. Mol. Immunol. 2019, 106, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, R.; Roychowdhury, A.; Ember, B.; Kumar, S.; Boons, G.-J.; Mariuzza, R.A. Structural Basis for Peptidoglycan Binding by Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 17168–17173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes, J.C.; Welchman, D.P.; Poidevin, M.; Lemaitre, B. Negative Regulation by Amidase PGRPs Shapes the Drosophila Antibacterial Response and Protects the Fly from Innocuous Infection. Immunity 2011, 35, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royet, J. Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins: Modulators of the Microbiome and Inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, T.; Liu, G.; Kang, D.; Ekengren, S.; Steiner, H.; Hultmark, D. A Family of Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins in the Fruit Fly Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 13772–13777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Gelius, E.; Liu, G.; Steiner, H.; Dziarski, R. Mammalian Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein Binds Peptidoglycan with High Affinity, Is Expressed in Neutrophils, and Inhibits Bacterial Growth. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 24490–24499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, H.; Ishibashi, J.; Fujita, K.; Nakajima, Y.; Sagisaka, A.; Tomimoto, K.; Suzuki, N.; Yoshiyama, M.; Kaneko, Y.; Iwasaki, T. A Genome-Wide Analysis of Genes and Gene Families Involved in Innate Immunity of Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 38, 1087–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Jing, Z.; Yu, Q.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, B.; Xing, L.; Zhang, H.; Wan, F.; Li, C. Antiviral Function of Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein in Spodoptera exigua (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Insect Sci. 2023, 30, 1092–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Ran, J.; Jia, C.; Mohamed, A.; Paredes-Montero, J.R.; Al-Akeel, R.K.; Zang, L.; Zhang, W.; Keyhani, N.O.; Eleftherianos, I. Developmental Transcriptomics Reveals Stage-Specific Immune Gene Expression Profiles in Spodoptera frugiperda. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Zou, Q.; Yu, G.; Liu, F.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Hu, F.; Wang, Z. Immunotranscriptomic Profiling of Spodoptera frugiperda Challenged by Different Pathogenic Microorganisms. Insects 2025, 16, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; He, H.-J.; Zhao, X.-F.; Wang, J.-X. Immune Responses of Helicoverpa armigera to Different Kinds of Pathogens. BMC Immunol. 2010, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankenhuyzen, K.V. Insecticidal Activity of Bacillus Thuringiensis Crystal Proteins. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2009, 101, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, A.; Likitvivatanavong, S.; Gill, S.S.; Soberón, M. Bacillus Thuringiensis: A Story of a Successful Bioinsecticide. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 41, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurat-Fuentes, J.L.; Heckel, D.G.; Ferré, J. Mechanisms of Resistance to Insecticidal Proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2021, 66, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, T.; Reichhart, J.-M.; Hoffmann, J.A.; Royet, J. Drosophila Toll Is Activated by Gram-Positive Bacteria through a Circulating Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein. Nature 2001, 414, 756–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemaitre, B.; Hoffmann, J. The Host Defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 25, 697–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhou, L.; Chen, F.; Peng, Y.; Lu, Z. Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein-S5 Functions as a Negative Regulator of the Antimicrobial Peptide Pathway in the Silkworm, Bombyx mori. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2016, 61, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capo, F.; Charroux, B.; Royet, J. Bacteria Sensing Mechanisms in Drosophila Gut: Local and Systemic Consequences. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2016, 64, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Long, Q.X.; Xie, J. Roles of Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein (PGRP) in Immunity and Implications for Novel Anti-Infective Measures. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2012, 22, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Kong, X.; Zhang, Z. Research Progress on the Dendrolimus Spp. Pheromone: From Identification to Molecular Recognition. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 829826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wu, P.; Xiong, Z.; Liu, N.; Zhao, N.; Ji, M.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, B. Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly Reveals Significant Gene Expansion in the Toll and IMD Signaling Pathways of Dendrolimus kikuchii. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 728418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.; He, J.Z. Study of Biological Characters of Dendrolimus kikuchii matsumura and Food Consumption of Its Larva. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2009, 37, 13122–13124. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An Ultra-Fast All-in-One FASTQ Preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A Fast Spliced Aligner with Low Memory Requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Su, F.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Tang, T.; Hu, Q.; Yu, X.-Q. Pattern Recognition Receptors in Drosophila Immune Responses. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2020, 102, 103468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, M.R.; Gasteiger, E.; Bairoch, A.; Sanchez, J.-C.; Williams, K.L.; Appel, R.D.; Hochstrasser, D.F. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools in the ExPASy Server. Methods Mol. Biol. 1999, 112, 531–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunkes, M.S.B.; Reddy, M.S. Characterization of the Regulatory Signatures of Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins of Apis cerana by in Silico Analysis. J. Apic. 2022, 37, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Yao, X.; Bai, S.; Wei, J.; An, S. Involvement of an Enhanced Immunity Mechanism in the Resistance to Bacillus Thuringiensis in Lepidopteran Pests. Insects 2023, 14, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paskewitz, S.M.; Andreev, O.; Shi, L. Gene Silencing of Serine Proteases Affects Melanization of Sephadex Beads in Anopheles gambiae. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006, 36, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista, M.A.M.; Miyata, T.; Miura, K.; Tanaka, T. RNA Interference-Mediated Knockdown of a Cytochrome P450, CYP6BG1, from the Diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella, Reduces Larval Resistance to Permethrin. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009, 39, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Lü, L.; Dai, W.; Zhang, W.; Lin, Z.; Dong, Y. Identification, Phylogeny and Expressional Profiles of Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein (PGRP) Gene Family in Sinonovacula Constricta. J. Ocean. Univ. China 2022, 21, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Huang, B.; Gao, M.; Li, Q.; Tao, Y.; Wang, Z. Molecular and Functional Characterization of Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins OfPGRP-a and OfPGRP-B in Ostrinia furnacalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Insects 2022, 13, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Song, X.; Wang, M. Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins in Hematophagous Arthropods. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2018, 83, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.-X.; Guo, M.-Y.; Geng, J.; Wei, X.-Q.; Huang, D.-W.; Xiao, J.-H. Genome-Wide Analysis of Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein Genes in Fig Wasps (Hymenoptera, Chalcidoidea). Insects 2020, 11, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S.; Byun, M.; Oh, B.-H. Crystal Structure of Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein LB from Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Immunol. 2003, 4, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.-J.; Zhan, M.-Y.; Ye, C.; Yu, X.-Q.; Rao, X.-J. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of a Short Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein from Silkworm Bombyx mori. Insect Mol. Biol. 2017, 26, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Liu, C.; He, Y.; Jiang, H.; Lu, Z. A Short-Type Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein from the Silkworm: Expression, Characterization and Involvement in the Prophenoloxidase Activation Pathway. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2014, 45, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Huang, X.; Gong, L.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z. Characterization of Immune-Related PGRP Gene Expression and Phenoloxidase Activity in Cry1Ac-Susceptible and-Resistant Plutella xylostella (L.). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2019, 160, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Dou, W.; Song, Z.-H.; Jin, T.-J.; Yuan, G.-R.; De Schutter, K.; Smagghe, G.; Wang, J.-J. Identification and Profiling of Bactrocera Dorsalis microRNAs and Their Potential Roles in Regulating the Developmental Transitions of Egg Hatching, Molting, Pupation and Adult Eclosion. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 127, 103475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanji, T.; Ip, Y.T. Regulators of the Toll and Imd Pathways in the Drosophila Innate Immune Response. Trends Immunol. 2005, 26, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebede, M.; Fite, T. RNA Interference (RNAi) Applications to the Management of Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae): Its Current Trends and Future Prospects. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 944774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene ID | PGRP Gene Name | Best-Matched Insect Gene (Species/Accession Number) | Amino Acid Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| D.kikuchii_LG01_G00316 | DkikPGRP-L1 | Trichoplusia ni (XP-026730977.1) | 55.8 |

| D.kikuchii_LG01_G00520 | DkikPGRP-L2 | Trichoplusia ni (XP-026738966.1) | 56.0 |

| D.kikuchii_LG22_G00198 | DkikPGRP-LC | Trichoplusia ni (XP-026739039.1) | 42.5 |

| D.kikuchii_LG23_G00044 | DkikPGRP-LE | Trichoplusia ni (XP-026739039.1) | 39.4 |

| D.kikuchii_LG01_G00331 | DkikPGRP-S1 | Galleria mellonella (XP-026757906.1) | 54.8 |

| D.kikuchii_LG20_G00235 | DkikPGRP-S2 | Samia ricini (BAF03520.1) | 65.5 |

| D.kikuchii_LG20_G00237 | DkikPGRP-S3 | Helicoverpa armigera (AHL58837.1) | 78.5 |

| D.kikuchii_LG20_G00236 | DkikPGRP-S4 | Leguminivora glycinivorella (AXS59129.1) | 64.6 |

| D.kikuchii_LG09_G00102 | DkikPGRP-S5 | Hyposmocoma kahamanoa (XP-026322322.1) | 57.7 |

| D.kikuchii_LG09_G00101 | DkikPGRP-S6 | Trichoplusia ni (XP-026737257.1) | 64.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Q.; Fu, X.; Zhao, N.; Yang, B.; Zhou, J. Genome-Wide Identification of PGRP Gene Family and Its Role in Dendrolimus kikuchii Immune Response Against Bacillus thuringiensis Infection. Biology 2025, 14, 1783. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121783

Tang Y, Wang Z, Guo Q, Fu X, Zhao N, Yang B, Zhou J. Genome-Wide Identification of PGRP Gene Family and Its Role in Dendrolimus kikuchii Immune Response Against Bacillus thuringiensis Infection. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1783. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121783

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Yanjiao, Zizhu Wang, Qiang Guo, Xue Fu, Ning Zhao, Bin Yang, and Jielong Zhou. 2025. "Genome-Wide Identification of PGRP Gene Family and Its Role in Dendrolimus kikuchii Immune Response Against Bacillus thuringiensis Infection" Biology 14, no. 12: 1783. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121783

APA StyleTang, Y., Wang, Z., Guo, Q., Fu, X., Zhao, N., Yang, B., & Zhou, J. (2025). Genome-Wide Identification of PGRP Gene Family and Its Role in Dendrolimus kikuchii Immune Response Against Bacillus thuringiensis Infection. Biology, 14(12), 1783. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121783