Contrasting Evolutionary Trajectories: Differential Population Dynamics and Gene Flow Patterns in Sympatric Halimeda discoidea and Halimeda macroloba

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

2.2. PCR Amplification and Sequencing

2.3. Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.4. Haplotype Analysis and Network Construction

2.5. Population Genetic Structure

2.6. Bayesian Clustering

2.7. Divergence Time Estimation

2.8. Gene Flow and Demographic Parameters

3. Results

3.1. Halimeda Species Diversity in the Xisha (Paracel) Islands: New Discoveries

3.2. tufA Sequence Characteristics and Haplotype Polymorphism in Halimeda

3.3. Genetic Divergence and Population Structure of H. discoidea

3.4. Population Dynamics and Evolutionary History of H. discoidea and H. macroloba

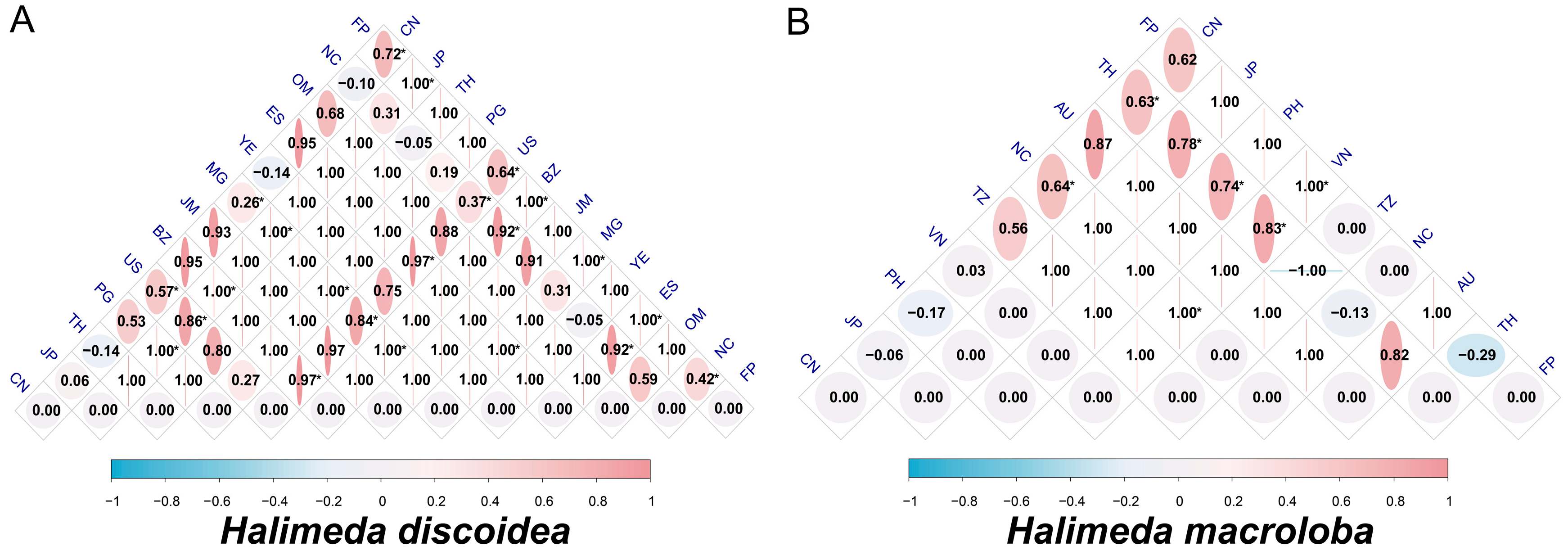

3.5. Inter-Population Genetic Differentiation (FST) in H. discoidea and H. macroloba

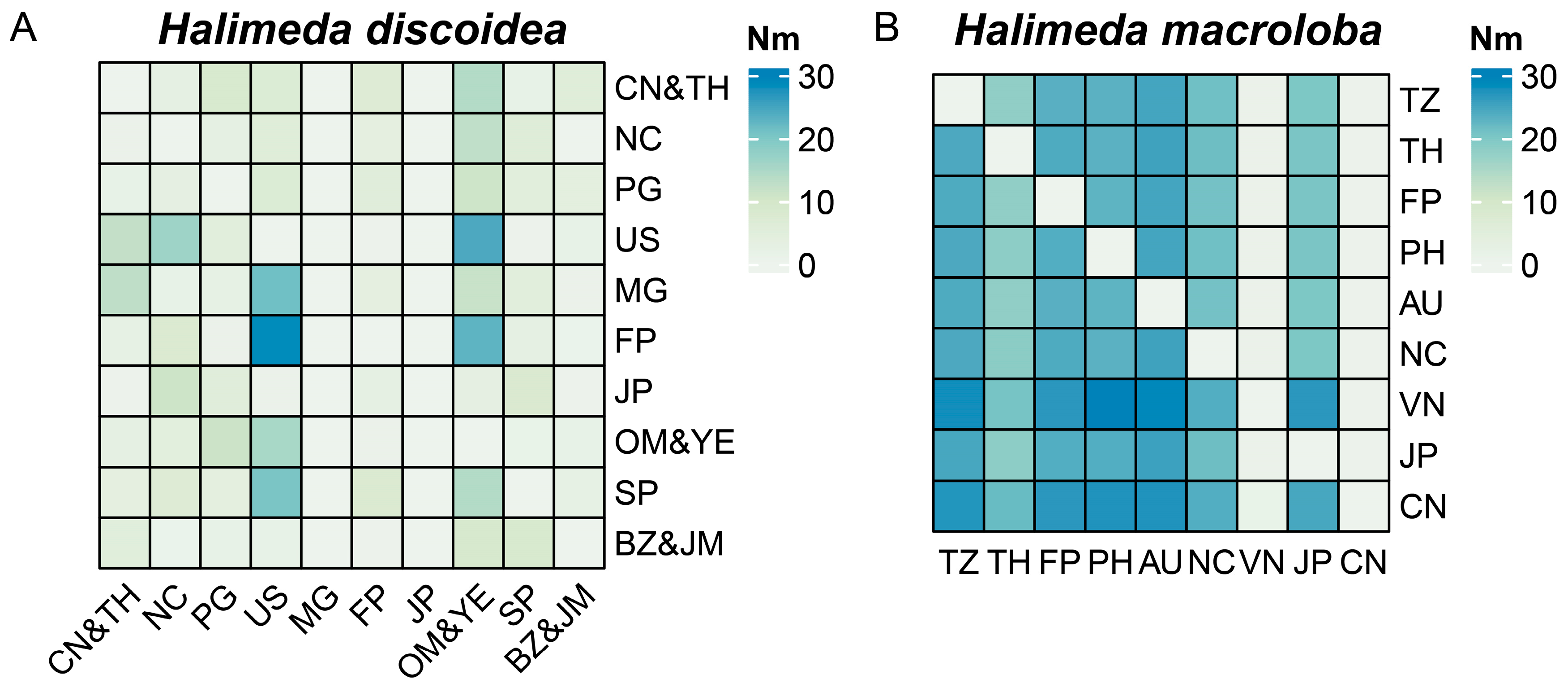

3.6. Gene Flow and Dispersal Mechanisms in H. discoidea and H. macroloba Across Geographic Regions

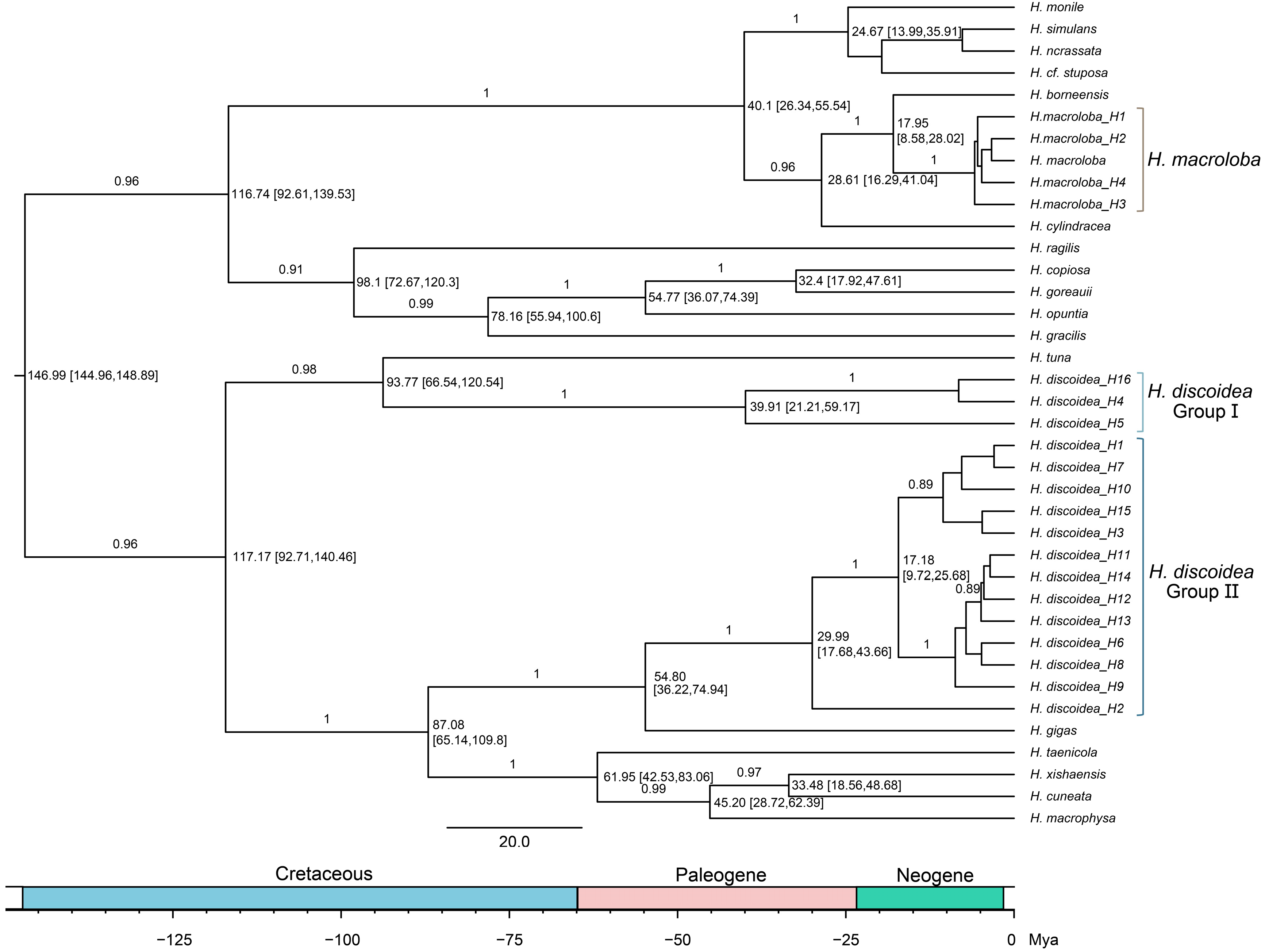

3.7. Phylogenetic Relationships and Divergence Times of Halimeda Species

4. Discussion

4.1. Halimeda Biogeography in the Xisha (Paracel) Islands: Insights from New Molecular Records

4.2. Contrasting Population Structures: High Fragmentation in H. Discoidea Vs. Relative Connectivity in H. macroloba

4.3. Divergent Gene Flow Regimes Explain Contrasting Genetic Structures

4.4. Deep Evolutionary Divergence Explains Contrasting Modern Population Structures

4.5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, S.; Hu, M.J.; Tong, Y.P.; Xia, Z.Y.; Tong, Y.C.; Sun, Y.Q.; Cao, J.X.; Zhang, J.H.; Liu, J.L.; Zhao, S.; et al. A review of volatile compounds in edible macroalgae. Food Res. Int. 2023, 165, 112559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pessarrodona, A.; Pedersen, M.F.; Wernberg, T.; Duarte, C.M.; Assis, J.; Bekkby, T.; Burrows, M.T.; Carlson, D.F.; Gattuso, J.; Gundersen, H.; et al. Carbon export from seaweed forests to deep ocean sinks. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.Q.; Xia, J.; Liu, J.L.; He, P.M. “Love-hate relationships” between antibiotics and marine algae: A review. Aquat. Toxicol. 2025, 286, 107459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillis-Colinvaux, L. Ecology and taxonomy of Halimeda: Primary producer of coral reefs. Adv. Mar. Biol. 1980, 17, 1–327. [Google Scholar]

- Littler, M.M.; Littler, D.S.; Blair, S.M.; Norris, J.N. Deep-water plant communities from an uncharted seamount off San Salvador Island, Bahamas: Distribution, abundance, and primary productivity. Deep. Sea Res. Part A Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 1986, 33, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, V.J.; Fenical, W. Novel bioactive diterpenoid metabolites from tropical marine algae of the genus Halimeda (Chlorophyta). Tetrahedron 1984, 40, 3053–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Seca, A.M.L.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Michalak, I.; Trincone, A.; Mishra, A.P.; Nigam, M.; Zam, W.; Martins, N. Current Trends on Seaweeds: Looking at Chemical Composition, Phytopharmacology, and Cosmetic Applications. Molecules 2019, 24, 4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, N.N.; Hamilton, S.L.; Tootell, J.S.; Smith, J.E. Species-specific consequences of ocean acidification for the calcareous tropical green algae Halimeda. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 440, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.L.; Zhang, Y.T.; Yang, F.F.; Long, L.J. Increased light availability enhances tolerance against ocean acidification-related stress in the calcifying macroalga Halimeda opuntia. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2022, 41, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, H.; De Clerck, O.; Kooistra, W.; Coppejans, E. Molecular and morphometric data pinpoint species boundaries in Halimeda section Rhipsalis (Bryopsidales, Chlorophyta). J. Phycol. 2005, 41, 606–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijoux, L.; Verbruggen, H.; Mattio, L.; Duong, N.; Payri, C. Diversity of Halimeda (Bryopsidales, Chlorophyta) in New Caledonia: A Combined Morphological and Molecular Study. J. Phycol. 2012, 48, 1465–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooistra, W.; Coppejans, E.G.G.; Payri, C. Molecular systematics, historical ecology, and phylogeography of Halimeda (Bryopsidales). Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2002, 24, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ximenes, C.F.; Cassano, V.; de Oliveira-Carvalho, M.D.; Bandeira-Pedrosa, M.E.; Gurgel, C.F.D.; Verbruggen, H.; Pereira, S.M.B. Systematics of the genus Halimeda (Bryopsidales, Chlorophyta) in Brazil including the description of Halimeda jolyana sp. nov. Phycologia 2017, 56, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, H.; De Clerck, O.; Schils, T.; Kooistra, W.; Coppejans, E. Evolution and phylogeography of Halimeda section Halimeda (Bryopsidales, Chlorophyta). Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2005, 37, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, B.P.; Thaker, V.S. DNA barcoding and traditional taxonomy: An integrated approach for biodiversity conservation. Genome 2017, 60, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phetcharat, S.; Pattarach, K.; Chen, P.C.; Wang, W.L.; Liu, S.L.; Mayakun, J. Species diversity and distribution of the calcareous green macroalgae Halimeda in Taiwan, Spratly Island, and Dongsha Atoll, with the proposal of Halimeda taiwanensis sp. nov. Phycol. Res. 2023, 71, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhang, L.S.; Wang, Z.Q.; Zhu, Z.J.; Long, L.J. Protein and metabolite acclimations to temperature variability in a calcareous green macroalga Halimeda macroloba. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1543591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, R.; Hanyuda, T.; Kawai, H. Taxonomic re-examination of Japanese Halimeda species using genetic markers, and proposal of a new species Halimeda ryukyuensis (Bryopsidales, Chlorophyta). Phycol. Res. 2015, 63, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis of Large Data Sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D. POPART: Full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Lischer, H.E.L. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: A new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2010, 10, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradis, E.; Claude, J.; Strimmer, K. APE: Analyses of Phylogenetics and Evolution in R language. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 289–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santorum, J.M.; Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Posada, D. jmodeltest.org: Selection of nucleotide substitution models on the cloud. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1310–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, H.; Ashworth, M.; LoDuca, S.T.; Vlaeminck, C.; Cocquyt, E.; Sauvage, T.; Zechman, F.W.; Littler, D.S.; Littler, M.M.; Leliaert, F.; et al. A multi-locus time-calibrated phylogeny of the siphonous green algae. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2009, 50, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, R.; Vaughan, T.G.; Barido-Sottani, J.; Duchêne, S.; Fourment, M.; Gavryushkina, A.; Heled, J.; Jones, G.; Kühnert, D.; De Maio, N.; et al. BEAST 2.5: An advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1006650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Xie, D.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A. Posterior Summarization in Bayesian Phylogenetics Using Tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, P. Comparison of Bayesian and maximum-likelihood inference of population genetic parameters. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zou, X.X.; Fu, Q.Y.; Bao, S.X. Morphological and molecular study on marine green alga, Halimeda velasquezii, first recorded on Hainan Island. J. Trop. Oceanogr. 2020, 69, 114–121, (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Arina, N.; Rozaimi, M.; Zainee, N.F.A. High localised diversity of Halimeda (Chlorophyta: Bryopsidales) in a tropical marine park from Pahang, Malaysia. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2019, 31, 100773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindi, F.; Pasella, M.M.; Lee, M.F.E.; Verbruggen, H. Phylogeography of the mediterranean green seaweed Halimeda tuna (Ulvophyceae, Chlorophyta). J. Phycol. 2020, 56, 1109–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.H.; Yao, J.T.; Roleda, M.Y.; Liang, Y.S.; Xu, R.; Lin, Y.D.; Gonzaga, S.M.C.; Du, Y.Q.; Duan, D.L. Genetic Diversity and Connectivity of Reef-Building Halimeda macroloba in the Indo-Pacific Region. Plants 2025, 14, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, S.M.; Yeong, H.Y.; Ganzon-Fortes, E.T.; Lewmanomont, K.; Prathep, A.; Gerung, G.S.; Tan, K.S. Marine algae of the South China Sea bordered by Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. Raffles Bull. Zool. 2016, 34, 13–59. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Nhat, N.T.N.; Nguyen, X.T.; Nguyen, V.X. Morphological variation and haplotype diversity of Halimeda macroloba and H. opuntia (Chlorophyta: Halimedaceae) from Southern Vietnam. Vietnam J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2022, 22, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Zainee, N.F.A.; Ismail, A.H.M.A.D.; Taip, M.E.; Ibrahim, N.A.Z.L.I.N.A.; Ismail, A.S.M.I.D.A. Diversity, distribution and taxonomy of Malaysian marine algae, Halimeda (Halimedaceae, Chlorophyta). Malay. Nat. J. 2018, 70, 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.P.; Huang, B.X.; Luan, R.X. New classification system of marine green algae of China. Guangxi Sci. 2015, 22, 201–210, (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Pongparadon, S.; Zuccarello, G.C.; Phang, S.M.; Kawai, H.; Hanyuda, T.; Prathep, A. Diversity of Halimeda (Chlorophyta) from the Thai–Malay Peninsula. Phycologia 2015, 54, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestion, E.; Clobert, J.; Cote, J. Dispersal response to climate change: Scaling down to intraspecific variation. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freestone, A.L.; Inouye, B.D. Dispersal limitation and environmental heterogeneity shape scale-dependent diversity patterns in plant communities. Ecology 2006, 87, 2425–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbruggen, H.; Tyberghein, L.; Pauly, K.; Vlaeminck, C.; Van Nieuwenhuyze, K.; Kooistra, W.; Leliaert, F.; De Clerck, O. Macroecology meets macroevolution: Evolutionary niche dynamics in the seaweed Halimeda. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2009, 18, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.Q.; Zhang, T.Y.; Liu, Y.J.; Nguyen, X.V.; Sun, Z.M.; Draisma, S.G.; Hu, Z.M. Low phylogeographic diversity in the calcified green macroalga Halimeda macroloba (Bryopsidales) in Southeast Asia. Algae 2025, 40, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohonak, A.J. Dispersal, gene flow, and population structure. Q. Rev. Biol. 1999, 74, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, D.J.; Hellenthal, G.; Myers, S.; Falush, D. Inference of population structure using dense haplotype data. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.G.; Smith, D.G.; Funnell, B.M. Atlas of Mesozoic and Cenozoic Coastlines; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rögl, F.; Steininger, F.F. Neogene Paratethys, Mediterranean and Indo-Pacific Seaways. Implications for the paleobiogeography of marine and terrestrial biotas. In Fossils and Climate; Brenchley, P.J., Ed.; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Chichester, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 171–200. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, P. Closing of the Central American Seaway and the Ice Age: A critical review. Paleoceanography 2008, 23, PA2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawver, L.A.; Gahagan, L.M. Evolution of Cenozoic seaways in the circum-Antarctic region. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2003, 198, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowlton, N.; Weigt, L.A. New dates and new rates for divergence across the Isthmus of Panama. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 1998, 265, 2257–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, G.J.; Larson, W.A.; Seeb, L.W.; Seeb, J.E. RAD seq provides unprecedented insights into molecular ecology and evolutionary genetics: Comment on Breaking RAD by Lowry et al. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2017, 17, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, M.E. Sequencing breakthroughs for genomic ecology and evolutionary biology. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2008, 8, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, K.H.; Graham, C.H.; Wiens, J.J. Integrating GIS-based environmental data into evolutionary biology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baguette, M.; Blanchet, S.; Legrand, D.; Stevens, V.M.; Turlure, C. Individual dispersal, landscape connectivity and ecological networks. Biol. Rev. 2013, 88, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinseel, E.; Sabbe, K.; Verleyen, E.; Vyverman, W. A new dawn for protist biogeography. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2024, 33, e13925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Area | Species | GenBank Information | Source | Collection Locality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN | China | Halimeda discoidea | H15 | This study | Xisha (Paracel) Islands, Sansha, Hainan |

| Halimeda discoidea | OP313765 | NCBI | Taiwan: Kenting National Park | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | MK922588 | NCBI | Taiwan: Kenting National Park | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | MW249121 | NCBI | Taiwan | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | H2 | This study | Xisha (Paracel) Islands, Sansha, Hainan | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | H22 | This study | Xisha (Paracel) Islands, Sansha, Hainan | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | H24 | This study | Xisha (Paracel) Islands, Sansha, Hainan | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | H25 | This study | Xisha (Paracel) Islands, Sansha, Hainan | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | H28 | This study | Xisha (Paracel) Islands, Sansha, Hainan | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | H32 | This study | Xisha (Paracel) Islands, Sansha, Hainan | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | PQ824575 | NCBI | Pratas Island | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | KU220841 | NCBI | Pratas Island | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | KU220837 | NCBI | Pratas Island | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | KU220838 | NCBI | Pratas Island | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | KU220839 | NCBI | Pratas Island | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | KU220840 | NCBI | Pratas Island | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | KU220836 | NCBI | Pratas Island | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | MK922585 | NCBI | China | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | PQ824576 | NCBI | China | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | MK922586 | NCBI | Taiwan: Taiping Island | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | MN879375 | NCBI | Taiwan: Taiping Island | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | MN879366 | NCBI | Taiwan: Taiping Island | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | MN879378 | NCBI | Taiwan: Taiping Island | ||

| JP | Japan | Halimeda discoidea | AB899303 | NCBI | Amami I., Kagoshima, Japan |

| Halimeda discoidea | AB899304 | NCBI | Ankyaba, Amami I., Kagoshima, Japan | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | AB899302 | NCBI | Amami I., Kagoshima, Japan | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | AB899301 | NCBI | Sani, Amami I., Kagoshima, Japan | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | KU361892 | NCBI | Kurima Island, Miyako | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | AB899309 | NCBI | Uken, Amami I., Kagoshima, Japan | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | AB899308 | NCBI | Shirahama, Amami I., Kagoshima | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | AB899310 | NCBI | Shiraho, Ishigaki I., Okinawa | ||

| TH | Thailand | Halimeda discoidea | KT887731 | NCBI | Thailand |

| Halimeda macroloba | PQ824574 | NCBI | Thailand | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | PQ824577 | NCBI | Thailand | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | PQ824579 | NCBI | Thailand | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | PQ824578 | NCBI | Thailand | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | PQ824580 | NCBI | Thailand | ||

| FP | French Polynesia | Halimeda discoidea | OR861097 | NCBI | French Polynesia: Society Islands, Moorea |

| Halimeda discoidea | OR861096 | NCBI | French Polynesia: Society Islands, Moorea | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | OR861095 | NCBI | French Polynesia: Society Islands, Moorea | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | JN644657 | NCBI | French Polynesia: Moorea | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | JN644656 | NCBI | French Polynesia: Moorea | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | OR861113 | NCBI | French Polynesia: Society Islands, Tahiti | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | OR861112 | NCBI | French Polynesia: Society Islands, Tahiti | ||

| PG | Papua New Guinea | Halimeda discoidea | KX808496 | NCBI | Papua New Guinea |

| Halimeda discoidea | KT887732 | NCBI | Papua New Guinea | ||

| MG | Madagascar | Halimeda discoidea | MW511210 | NCBI | Madagascar: Antsiranana Bay, Baie de Tonnerre |

| Halimeda discoidea | MW511214 | NCBI | Madagascar: Antsiranana Bay, Orangea | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | MW511213 | NCBI | Madagascar: Antsiranana Bay, Petite passe Orangea | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | MW511212 | NCBI | Madagascar: Antsiranana Bay, Orangea | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | MW511211 | NCBI | Madagascar: Antsiranana Bay, Orangea | ||

| US | USA | Halimeda discoidea | KY206005 | NCBI | Oahu, Hunakai Beach |

| Halimeda discoidea | KY205959 | NCBI | Oahu, Hunakai Beach | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | KY205982 | NCBI | Oahu, Hunakai Beach | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | KY205950 | NCBI | Oahu, Hunakai Beach | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | KY205934 | NCBI | Oahu, Hunakai Beach | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | OM460628 | NCBI | Kaneohe Bay, Kapaka Island, intertidal zone | ||

| NC | New Caledonia | Halimeda discoidea | JN644661 | NCBI | New Caledonia |

| Halimeda discoidea | JN644660 | NCBI | New Caledonia | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | JN644659 | NCBI | New Caledonia | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | JN644658 | NCBI | New Caledonia | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | JN644655 | NCBI | New Caledonia: Chesterfield | ||

| Halimeda discoidea | JN644654 | NCBI | New Caledonia | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | JN644691 | NCBI | New Caledonia | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | JN644692 | NCBI | New Caledonia | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | JN644693 | NCBI | New Caledonia | ||

| OM | Oman | Halimeda discoidea | AY826359 | NCBI | Oman |

| JM | Jamaica | Halimeda discoidea | AY826362 | NCBI | Jamaica |

| YE | Yemen | Halimeda discoidea | AY826360 | NCBI | Yemen: Socotra |

| SP | Spain | Halimeda discoidea | AY826361 | NCBI | Gran Canaria |

| Halimeda discoidea | KT887730 | NCBI | Fuerteventura | ||

| BZ | Belize | Halimeda discoidea | OM460625 | NCBI | Carrie Bow Cay |

| Halimeda discoidea | OM460613 | NCBI | Carrie Bow Cay | ||

| VN | Viet Nam | Halimeda macroloba | OL422177 | NCBI | Con Dao |

| Halimeda macroloba | OL422174 | NCBI | Viet NaM | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | OL422175 | NCBI | Ninh Thuan | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | OL422173 | NCBI | Nha Trang | ||

| Halimeda macroloba | OL422176 | NCBI | Phy Quy | ||

| PH | Philippines | Halimeda macroloba | PQ824581 | NCBI | Philippines |

| Halimeda macroloba | PQ824582 | NCBI | Philippines | ||

| AU | Australia | Halimeda macroloba | HM140244 | NCBI | Lizard Island, Coconut Beach |

| TZ | Tanzania | Halimeda macroloba | AM049960 | NCBI | Zanzibar, Nungwi |

| Symbol | Country/Region | Species | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halimeda discoidea | Halimeda macroloba | ||||||||||

| Number of Samples (n) | Polymorphism Sites (S) | Haplotype (Sample Numbers) | Haplotype Diversity (Hd) | Nucleotide Diversity (π/Pi) | Number of Samples (n) | Polymorphism Sites (S) | Haplotype (Sample Numbers) | Haplotype Diversity (Hd) | Nucleotide Diversity (π/Pi) | ||

| CN | China | 4 | 8 | H1(3), H6(1) | 0.500 ± 0.265 | 0.00658 ± 0.265 | 19 | 1 | H1(15), H2(4) | 0.341 ± 0.111 | 0.00049 ± 0.00016 |

| JP | Japan | 5 | 0 | H1(5) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | H1(3) | 0 | 0 |

| TH | Thailand | 1 | 0 | H10(1) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | H2(4), H3(1) | 0.400 ± 0.237 | 0.00056 ± 0.00033 |

| FP | French Polynesia | 5 | 0 | H8(5) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | H2(2) | 0 | 0 |

| PG | Papua New Guinea | 2 | 0 | H6(2) | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| MG | Madagascar | 5 | 0 | H15(5) | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| US | USA | 6 | 6 | H11(3), H12(1), H13(1), H14(1) | 0.8000 ± 0.172 | 0.00329 ± 0.00113 | - | - | - | - | - |

| NC | New Caledonia | 6 | 10 | H1(2), H6(1), H7(1), H9(2) | 0.867 ± 0.129 | 0.00888 ± 0.00168 | 3 | 0 | H2(3) | 0 | 0 |

| OM | Oman | 1 | 0 | H2(1) | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| JM | Jamaica | 1 | 0 | H5(1) | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| YE | Yemen | 1 | 0 | H3(1) | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| ES | Spain | 1 | 0 | H4(2) | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| BZ | Belize | 2 | 0 | H16(2) | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| VN | Viet NaM | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | 0 | H1(5) | 0 | 0 |

| PH | Philippines | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 0 | H1(2) | 0 | 0 |

| AU | Australia | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0 | H4(1) | 0 | 0 |

| TZ | Tanzania | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0 | H2(1) | 0 | 0 |

| Total | Total | 41 | 81 | - | 0.906 ± 0.027 | 0.02765 ± 0.00686 | 41 | 4 | - | 0.523 ± 0.00286 | 0.00089 ± 0.00016 |

| Species | Number of Samples | Fu’s Fs, p-Value | Tajima’s D, p-Value | Ewens-Watterson Test (Obs/Exp), p-Value | Chakraborty’s Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halimeda discoidea | 41 | 3.56909, 0.91300 | −0.40625, 0.32600 | 0.11600/0.11375, 0.618 | 0.45563 |

| Halimeda macroloba | 41 | −0.42185, 0.35400 | −0.76354, 0.23500 | 0.48959/0.050546, 0.545 | 0.54814 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tong, Y.; Liu, W.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, Q. Contrasting Evolutionary Trajectories: Differential Population Dynamics and Gene Flow Patterns in Sympatric Halimeda discoidea and Halimeda macroloba. Biology 2025, 14, 1782. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121782

Tong Y, Liu W, Sun Y, Liu J, Yang Q. Contrasting Evolutionary Trajectories: Differential Population Dynamics and Gene Flow Patterns in Sympatric Halimeda discoidea and Halimeda macroloba. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1782. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121782

Chicago/Turabian StyleTong, Yichao, Wei Liu, Yuqing Sun, Jinlin Liu, and Qunhui Yang. 2025. "Contrasting Evolutionary Trajectories: Differential Population Dynamics and Gene Flow Patterns in Sympatric Halimeda discoidea and Halimeda macroloba" Biology 14, no. 12: 1782. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121782

APA StyleTong, Y., Liu, W., Sun, Y., Liu, J., & Yang, Q. (2025). Contrasting Evolutionary Trajectories: Differential Population Dynamics and Gene Flow Patterns in Sympatric Halimeda discoidea and Halimeda macroloba. Biology, 14(12), 1782. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121782