Life History of the Giant Looper Moth Ascotis selenaria (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) in Eucalyptus Plantations and the Effect of Adult Mating Age on Fecundity

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Rearing

2.2. Morphological and Molecular Identification

2.3. Study of Life History and Developmental Characteristics

2.3.1. Generation Duration and Annual Life History

2.3.2. Larval Instar Division, Morphological Measurement, and Feeding Analysis

2.4. Adult Reproductive Biology Study

2.4.1. Dissection of Male and Female Reproductive Systems

2.4.2. Relationship Between Ovarian Development and Adult Age

2.4.3. Experimental Design for Reproductive Capacity

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Taxonomic Identification of Species

3.2. Biological Characteristics and Developmental Patterns

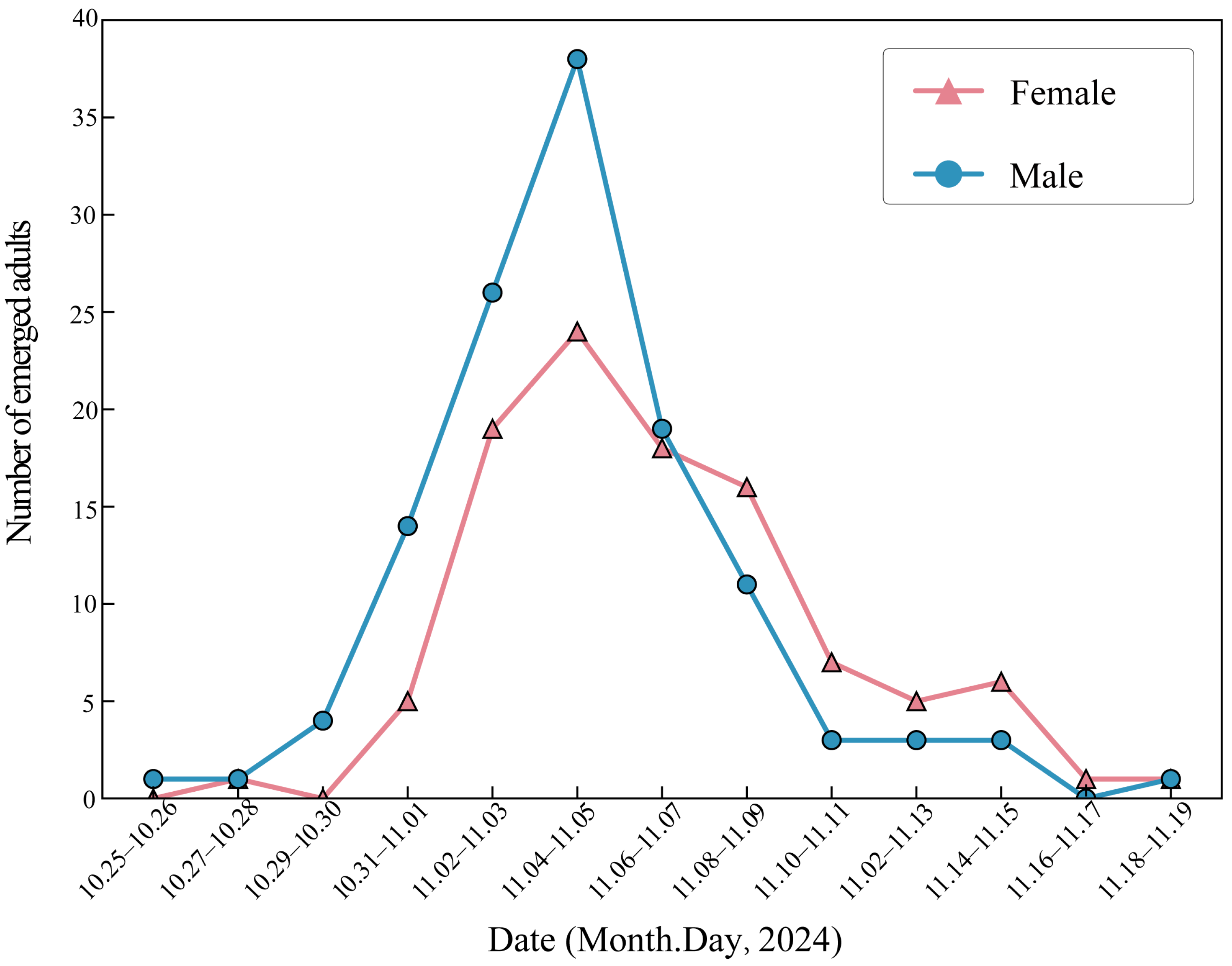

3.2.1. Key Developmental Periods and Annual Life History

3.2.2. Larval Head Capsule Width, Body Length, and Feeding Volume by Instar

3.3. Adult Reproductive Biology

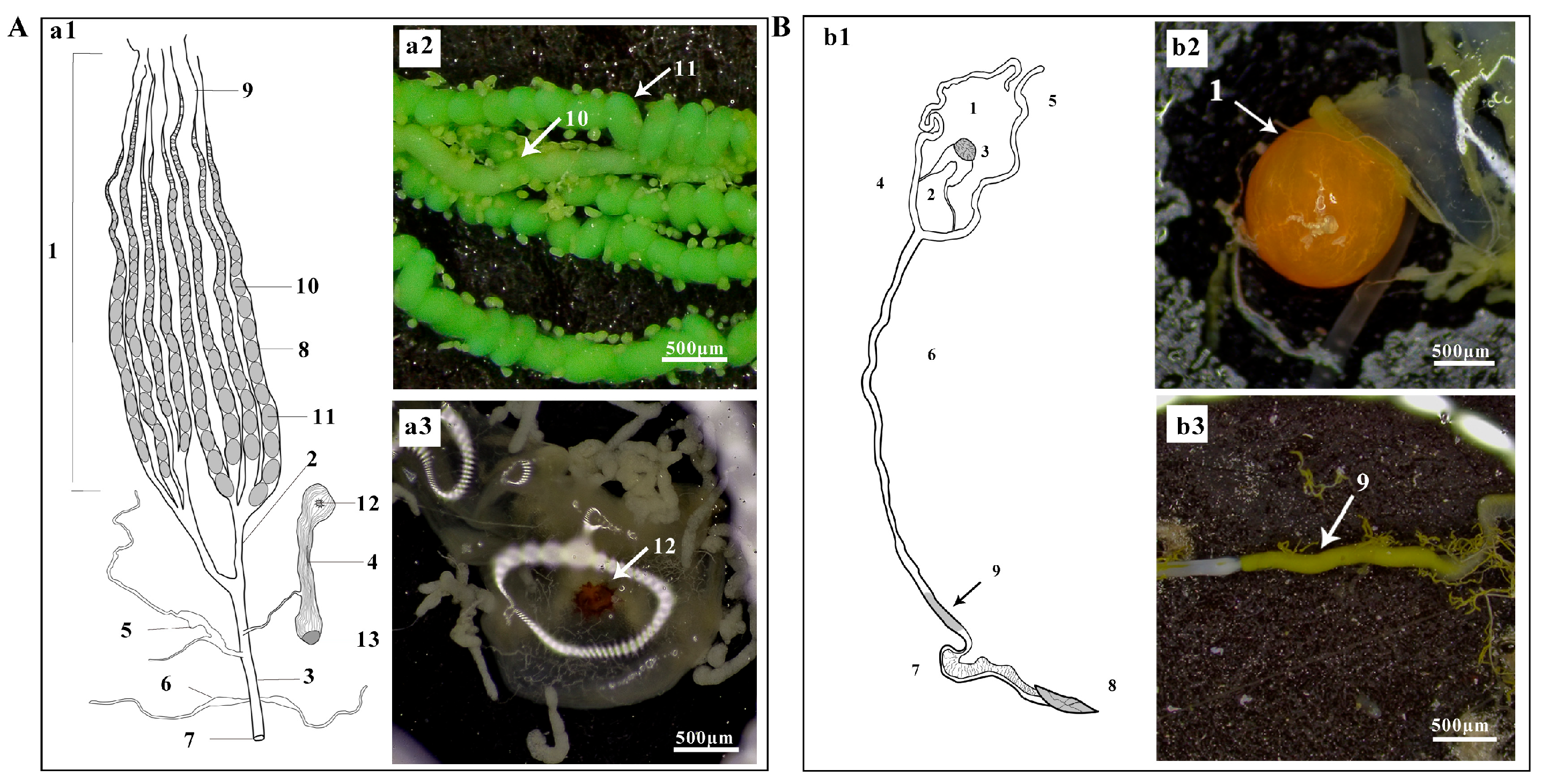

3.3.1. Morphology of Male and Female Reproductive Systems

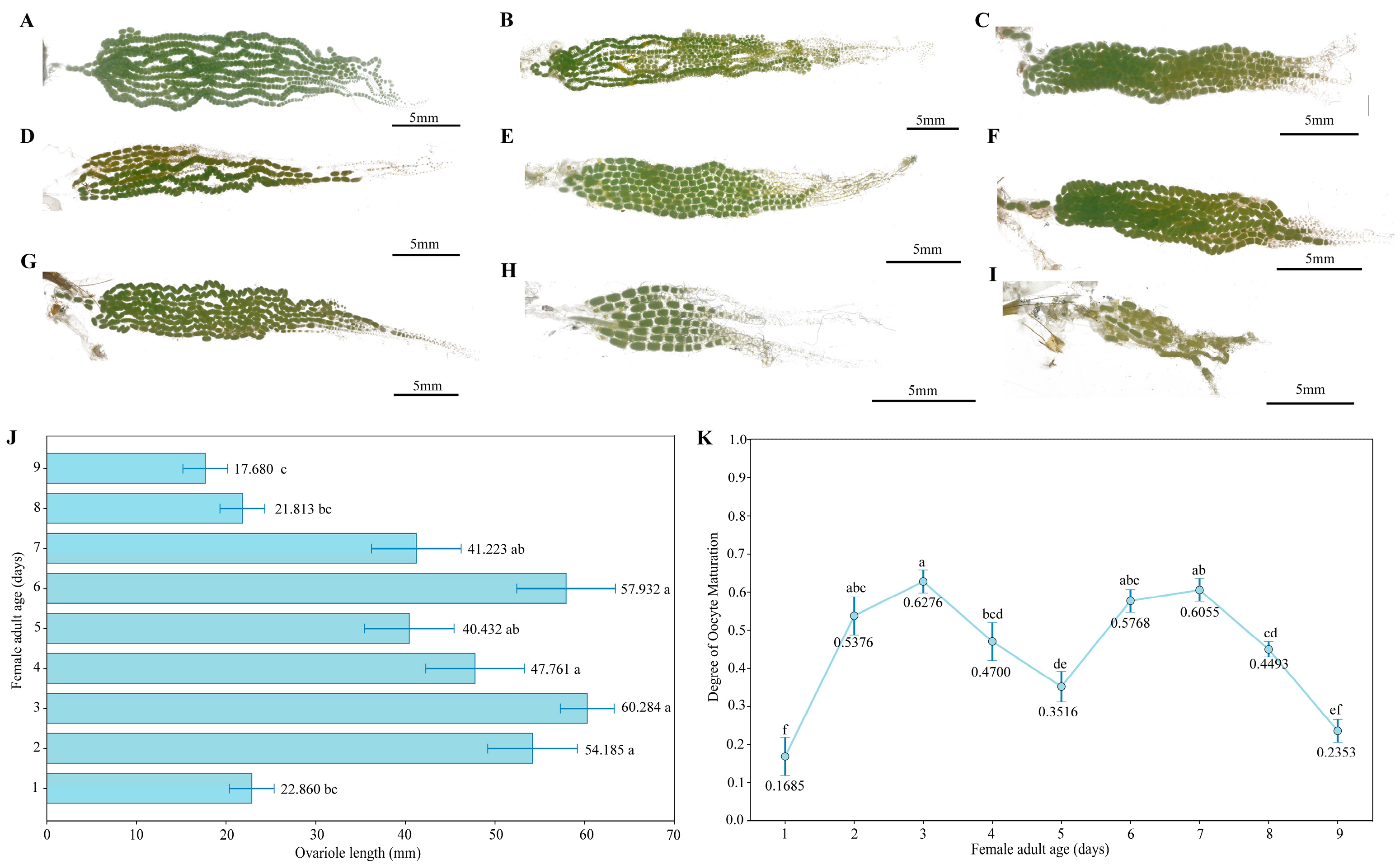

3.3.2. Ovarian Development Progress in Female Moths

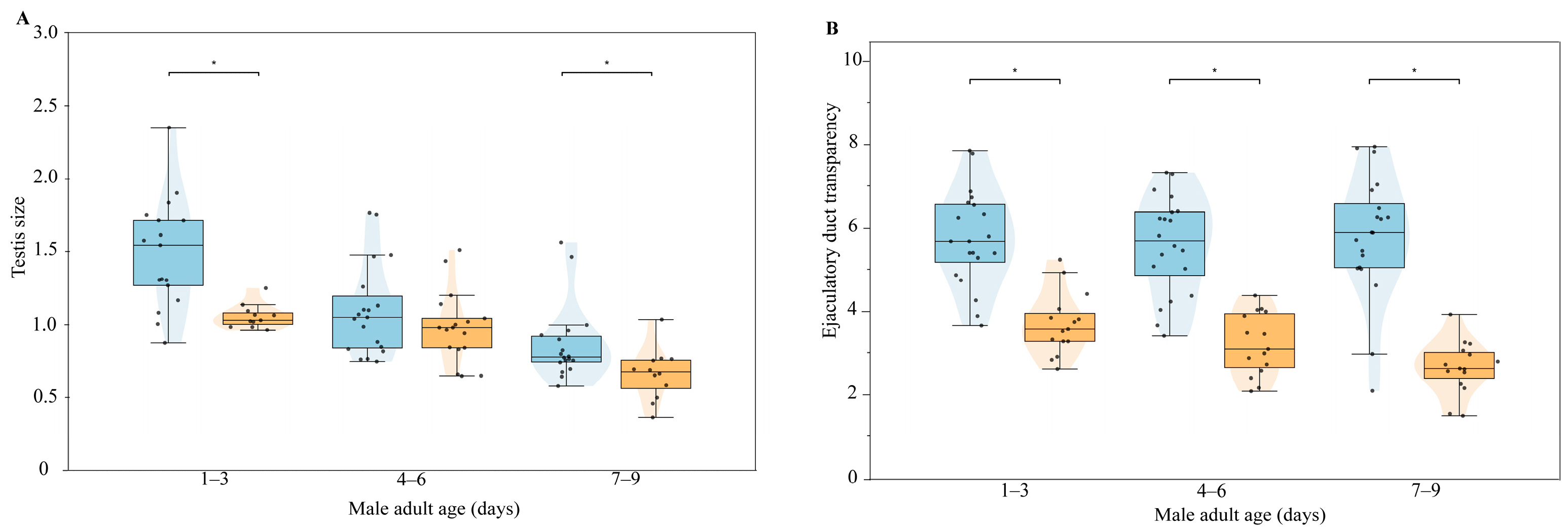

3.3.3. Changes in Male Internal Reproductive System with Age and Mating Status

3.3.4. Effect of Adult Age on Reproductive Capacity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, Y.; Arnold, R.J.; Wu, Z.; Chen, S.; Du, A.; Luo, J. Advances in Eucalypt Research in China. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2017, 4, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.A. Mitigating Biodiversity Concerns in Eucalyptus Plantations Located in South China. J. Biosci. Med. 2015, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmart, C.P.; Edwards, P.B. Insect Herbivory on Eucalyptus. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1991, 36, 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avisar, D.; Manoeli, A.; dos Santos, A.A.; Porto, A.C.D.M.; Rocha, C.D.S.; Zauza, E.; Gonzalez, E.R.; Soliman, E.; Gonsalves, J.M.W.; Bombonato, L.; et al. Genetically Engineered Eucalyptus Expressing Pesticidal Proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis for Insect Resistance: A Risk Assessment Evaluation Perspective. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1322985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiotto, T.C.; Barbosa, M.C.; Guerreiro, J.C.; Prado, E.P.; Masson, M.V.; Tavares, W.S.; Wilcken, C.F.; Zanuncio, J.C.; Ferreira-Filho, P.J. Ecological Importance of Lepidopteran Defoliators on Eucalyptus Plantations Based in Faunistic and Natural Enemy Analyses. Braz. J. Biol. 2023, 83, e268747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossé, A.A.; Cyjon, R.; Moore, I.; Wysoki, M.; Becker, D. Sex Pheromone Components of the Giant Looper, Boarmia selenaria Schiff. (Lepidoptera: Geometridae): Identification, Synthesis, Electrophysiological Evaluation, and Behavioral Activity. J. Chem. Ecol. 1992, 18, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, J.M.; Bigger, M.; Hillocks, R.J. (Eds.) Insects That Feed on Buds, Leaves, Green Shoots and Flowers. In Coffee Pests, Diseases and Their Management; CABI Books; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2007; pp. 91–144. ISBN 978-1-84593-129-2. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.S.; Park, Y.M.; Kim, D.-S. Seasonal Occurrence and Damage of Geometrid Moths with Particular Emphasis on Ascotis selenaria (Geometridae: Lepidoptera) in Citrus Orchards in Jeju, Korea. Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 2011, 50, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.S.; Kim, D.-S. Effect of Temperature on the Fecundity and Longevity of Ascotis selenaria (Lepidoptera: Geometridae): Developing an Oviposition Model. J. Econ. Entomol. 2016, 109, 1267–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysoki, M. A Bibliography of the Giant Looper, Boarmia (Ascotis) Selenaria Schiffermüller, 1775 (Lepidoptera: Geometridae), for the Years 1913–1981. Phytoparasitica 1982, 10, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, N.; Kalia, S.; Sambath, S.; Joshi, K.C. First Report of Ascotis selenaria imparata Walk. (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) as a Pest of Moringa Pterygosperma Gertn. Indian For. 1996, 122, 1075–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.; Arcot, Y.; Medina, R.F.; Bernal, J.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Akbulut, M.E.S. Integrated Pest Management: An Update on the Sustainability Approach to Crop Protection. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 41130–41147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.-H.; Itza, B.; Kafle, L.; Chang, T.-Y. Life Table Study of Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on Three Host Plants under Laboratory Conditions. Insects 2023, 14, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepens, M.H.M.; Wysoki, M. Reproductive Organs of the Giant Looper, Boarmia selenaria Schiffermüller (Leopidotera: Geometridae). Int. J. Insect Morphol. Embryol. 1986, 15, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Wang, J.; Jiang, N. Fauna of Drepanidae and Geometridae in Wuyishan National Park; World Publishing Corporation: Beijing, China, 2021; p. 556. [Google Scholar]

- Dyar, H.G. The Number of Molts of Lepidopterous Larvae. Psyche J. Entomol. 1890, 5, 23871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Yang, F.; Zhou, C.; Shen, H.-M.; Wang, B.-B.; Zeng, J.; Reynolds, D.R.; Chapman, J.W.; Hu, G. Climate Change Is Leading to an Ecological Trap in a Migratory Insect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2422595122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Shashank, P.R.; Meshram, N.M.; Subramanian, S.; Jeer, M.; Kalleshwaraswamy, C.M.; Chavan, S.M.; Jindal, J.; Suby, S.B. Molecular Diversity of Sesamia inferens (Walker, 1856) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) from India. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, G.M.; Kawahara, A.Y.; Daniels, J.C.; Bateman, C.C.; Scheffers, B.R. Climate Change Effects on Animal Ecology: Butterflies and Moths as a Case Study. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2021, 96, 2113–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.-F.; Lv, M.-Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.-C.; Liu, Z.; Lin, X.-L. Cryptic Diversity and Climatic Niche Divergence of Brillia Kieffer (Diptera: Chironomidae): Insights from a Global DNA Barcode Dataset. Insects 2025, 16, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, P.E. The Giant Coffee Looper, Ascotis selenaria reciprocaria Walk. (Lepidoptera: Geometridae). East Afr. Agric. For. J. 1963, 29, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Thapa, R.S.; Singh, P.; Thapa, R.S. Defoliation Epidemic of Ascotis selenaria imparata Walk. (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) in Sal Forest of Asarori Range, West Dehra Dun Division. Indian For. 1988, 114, 269–274. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, L. Insect Developmental Plasticity: The Role in a Changing Environment. Cardinal Edge 2021, 1, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.J.; Cunningham, C.B.; Bretman, A.; Duncan, E.J. One Genome, Multiple Phenotypes: Decoding the Evolution and Mechanisms of Environmentally Induced Developmental Plasticity in Insects. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2023, 51, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, Y.K.; Beldade, P. Thermal Plasticity in Insects’ Response to Climate Change and to Multifactorial Environments. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperk, T.; Tammaru, T.; Nylin, S. Intraspecific Variability in Number of Larval Instars in Insects. J. Econ. Entomol. 2007, 100, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsolver, J.G. Variation in Growth and Instar Number in Field and Laboratory Manduca sexta. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 274, 977–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarević, J.; Milanović, S.; Šešlija Jovanović, D.; Janković-Tomanić, M. Temperature- and Diet-Induced Plasticity of Growth and Digestive Enzymes Activity in Spongy Moth Larvae. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Li, D.; Wang, G.; Wu, L. Diet Affects the Temperature–Size Relationship in the Blowfly Aldrichina grahami. Insects 2024, 15, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellau, H.; Sandre, S.-L.; Tammaru, T. Effect of Host Species on Larval Growth Differs between Instars: The Case of a Geometrid Moth (Lepidoptera: Geometridae). Eur. J. Entomol. 2013, 110, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tettamanti, G.; Grimaldi, A.; Pennacchio, F.; de Eguileor, M. Lepidopteran Larval Midgut during Prepupal Instar: Digestion or Self-Digestion? Autophagy 2007, 3, 630–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashe-Jepson, E.; Hayes, M.P.; Hitchcock, G.E.; Wingader, K.; Turner, E.C.; Bladon, A.J. Day-flying Lepidoptera Larvae Have a Poorer Ability to Thermoregulate than Adults. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picanço Filho, M.C.; Lima, E.; Carmo, D.d.G.d.; Pallini, A.; Walerius, A.H.; da Silva, R.S.; Sant’Ana, L.C.d.S.; Lopes, P.H.Q.; Picanço, M.C. Economic Injury Levels and Economic Thresholds for Leucoptera coffeella as a Function of Insecticide Application Technology in Organic and Conventional Coffee (Coffea arabica), Farms. Plants 2024, 13, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon, D.F.; Gutierrez-Illan, J.; Crowder, D.W. Assessing Pest Control Treatments from Phenology Models and Field Data. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 1851–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, T.; Hovestadt, T.; Mitesser, O.; Hölker, F. High Female Survival Promotes Evolution of Protogyny and Sexual Conflict. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerström, T.; Wiklund, C. Why Do Males Emerge before Females? Protandry as a Mating Strategy in Male and Female Butterflies. Oecologia 1982, 52, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, W.J.; Saccheri, I.J. Male Emergence Schedule and Dispersal Behaviour Are Modified by Mate Availability in Heterogeneous Landscapes: Evidence from the Orange-Tip Butterfly. PeerJ 2015, 3, e707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morbey, Y.E. Protandry, Sexual Size Dimorphism, and Adaptive Growth. J. Theor. Biol. 2013, 339, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morbey, Y.E.; Ydenberg, R.C. Protandrous Arrival Timing to Breeding Areas: A Review. Ecol. Lett. 2001, 4, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, E.; Calabrese, J.M.; Rhainds, M.; Fagan, W.F. How Protandry and Protogyny Affect Female Mating Failure: A Spatial Population Model. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2013, 146, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.-L.; Liu, J.; Lu, W.; He, X.Z.; Wang, Q. Mating Delay Reduces Reproductive Performance but Not Longevity in a Monandrous Moth. J. Insect Sci. 2020, 20, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.-P.; Fang, Y.-L.; Zhang, Z.-N. Effects of Delayed Mating on the Fecundity, Fertility and Longevity of Females of Diamondback Moth, Plutella xylostella. Insect Sci. 2011, 18, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Vila, L.M.; Rodríguez-Molina, M.C.; Stockel, J. Delayed Mating Reduces Reproductive Output of Female European Grapevine Moth, Lobesia botrana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 2002, 92, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenheim, J.A.; Heimpel, G.E.; Mangel, M. Egg Maturation, Egg Resorption and the Costliness of Transient Egg Limitation in Insects. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2000, 267, 1565–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telfer, W.H. Egg Formation in Lepidoptera. J. Insect Sci. 2009, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y. Throwing Dice, but Not Always: Bet-Hedging Strategy of Parthenogenesis. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.; Rauter, C. Bet-Hedging and the Evolution of Multiple Mating. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2003, 5, 273–286. [Google Scholar]

- Yasui, Y. Female Multiple Mating as a Genetic Bet-Hedging Strategy When Mate Choice Criteria Are Unreliable. Ecol. Res. 2001, 16, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardé, R.T.; Minks, A.K. Control of Moth Pests by Mating Disruption: Successes and Constraints. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1995, 40, 559–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, A.K. Neuroendocrine Control of Sex Pheromone Biosynthesis in Lepidoptera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1993, 38, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusson, M.; McNeil, J.N. Involvement of Juvenile Hormone in the Regulation of Pheromone Release Activities in a Moth. Science 1989, 243, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onayemi, S.O.; Rincon, D.F.; Bahder, B.W.; Crowder, D.W.; Walsh, D.B. Optimizing Insecticide Timings for the Grape Mealybug, Pseudococcus maritimus (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) Based on Pheromone Trap Capture Data. J. Econ. Entomol. 2025, 118, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Ye, J.-J.; Liu, S.-R.; Chen, M.-Y.; Bai, T.-F.; Li, J.-W.; Yan, S.-W.; Huang, J.-R.; Deng, J.-Y.; Keesey, I.W.; et al. Optimizing Sex Pheromone Lures for Male Trapping Specificity between Spodoptera frugiperda and Mythimna loreyi. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Developmental Stage | Instar/Sex | Sample Size (n) | Duration (Days) | Head Capsule Width (mm) | Body Length (mm) | Feeding Volume (g) (% of Total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egg | — | 1022 | 5.60 ± 0.221 | — | — | — |

| Larva | 1st Instar | 15 | 3.60 ± 0.400 b | 0.29 ± 0.004 f | 2.90 ± 0.076 f | 0.006 (0.14%) c |

| 2nd Instar | 13 | 6.08 ± 0.702 a | 0.46 ± 0.011 e | 4.27 ± 0.070 e | 0.017 (0.39%) c | |

| 3rd Instar | 13 | 3.85 ± 0.478 b | 0.72 ± 0.012 d | 7.08 ± 0.183 d | 0.040 (0.92%) c | |

| 4th Instar | 14 | 3.07 ± 0.245 b | 1.26 ± 0.046 c | 13.53 ± 0.546 c | 0.229 (5.28%) bc | |

| 5th Instar | 15 | 3.78 ± 0.236 b | 2.10 ± 0.047 b | 23.22 ± 0.429 b | 0.590 (13.59%) b | |

| 6th Instar | 14 | 7.14 ± 0.376 a | 3.33 ± 0.055 a | 39.81 ± 0.826 a | 3.459 (79.68%) a | |

| Prepupa | — | 14 | 2.57 ± 0.137 | — | — | — |

| Pupa | Female | 104 | 9.57 ± 0.885 b | — | — | — |

| Male | 124 | 9.97 ± 0.775 a | — | — | — | |

| Adult | Female | 59 | 6.14 ± 2.063 b | — | — | — |

| Male | 105 | 7.29 ± 2.931 a | — | — | — | |

| Statistics | F/t-value | — | F5,78 = 14.74 | F5,78 = 1033.67 | F5,78 = 985.01 | F5,78 = 118.25 |

| p-value | — | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| Growth Model | Equation | — | — | y = 0.1721e0.4948x | y = 1.5457e0.5379x | — |

| R2 | — | — | 0.9989 | 0.9958 | — |

| Female Age (Days) | Male Age (Days) | Egg Production | Egg Hatchability (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–3 | 1–3 | 632.92 ± 58.30 | 88.00 ± 3.45 |

| 4–6 | 458.50 ± 56.59 | 92.37 ± 1.84 | |

| 7–9 | 317.67 ± 16.05 | 91.31 ± 1.71 | |

| 4–6 | 1–3 | 361.25 ± 48.46 | 80.65 ± 2.39 |

| 4–6 | 422.80 ± 72.93 | 80.41 ± 9.60 | |

| 7–9 | 382.75 ± 60.31 | 79.25 ± 7.14 | |

| 7–9 | 1–3 | 152.50 ± 37.77 | 54.58 ± 0.87 |

| 4–6 | 121.67 ± 50.24 | 37.38 ± 5.16 | |

| 7–9 | 58.33 ± 20.19 | 23.02 ± 7.11 | |

| Two-way ANOVA | F-value (p-value) | F-value (p-value) | |

| Source of Variation | |||

| Female Age (F) | F2,63 = 29.62 (p < 0.001) | F2,27 = 59.40 (p < 0.001) | |

| Male Age (M) | F2,63 = 3.92 (p = 0.025) | F2,27 = 1.31 (p = 0.287) | |

| Interaction (F × M) | F4,63 = 2.46 (p = 0.055) | F4,27 = 2.41 (p = 0.074) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, S.; Yang, M.; He, R.; Liu, B.; Wang, S.; Yang, Z.; Hu, P. Life History of the Giant Looper Moth Ascotis selenaria (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) in Eucalyptus Plantations and the Effect of Adult Mating Age on Fecundity. Biology 2025, 14, 1780. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121780

Yuan S, Yang M, He R, Liu B, Wang S, Yang Z, Hu P. Life History of the Giant Looper Moth Ascotis selenaria (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) in Eucalyptus Plantations and the Effect of Adult Mating Age on Fecundity. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1780. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121780

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Shuai, Mengjun Yang, Rijiao He, Bin Liu, Sijia Wang, Zhende Yang, and Ping Hu. 2025. "Life History of the Giant Looper Moth Ascotis selenaria (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) in Eucalyptus Plantations and the Effect of Adult Mating Age on Fecundity" Biology 14, no. 12: 1780. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121780

APA StyleYuan, S., Yang, M., He, R., Liu, B., Wang, S., Yang, Z., & Hu, P. (2025). Life History of the Giant Looper Moth Ascotis selenaria (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) in Eucalyptus Plantations and the Effect of Adult Mating Age on Fecundity. Biology, 14(12), 1780. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121780