Watching the South China Sea—Portiodora (Iridaceae), a New Genus for Iris speculatrix Based on Comprehensive Evidence: The Contribution of Taxonomic Resolution to Biodiversity Conservation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Taxonomic Treatment

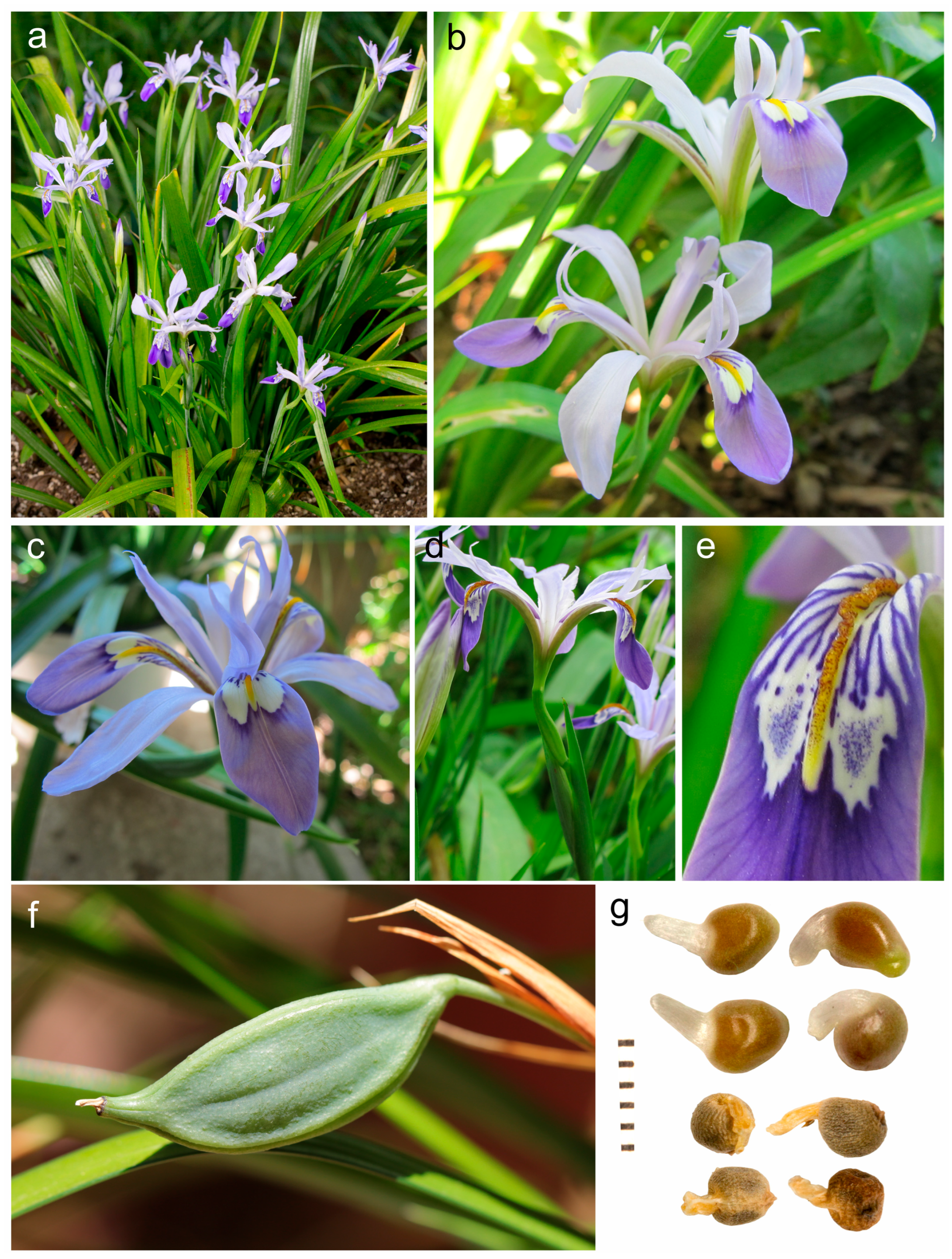

3.1.1. Portiodora M.B.Crespo, Mart.-Azorín & Mavrodiev gen. nov.

Type Species: Portiodora speculatrix (Hance) M.B.Crespo, Mart.-Azorín & Mavrodiev

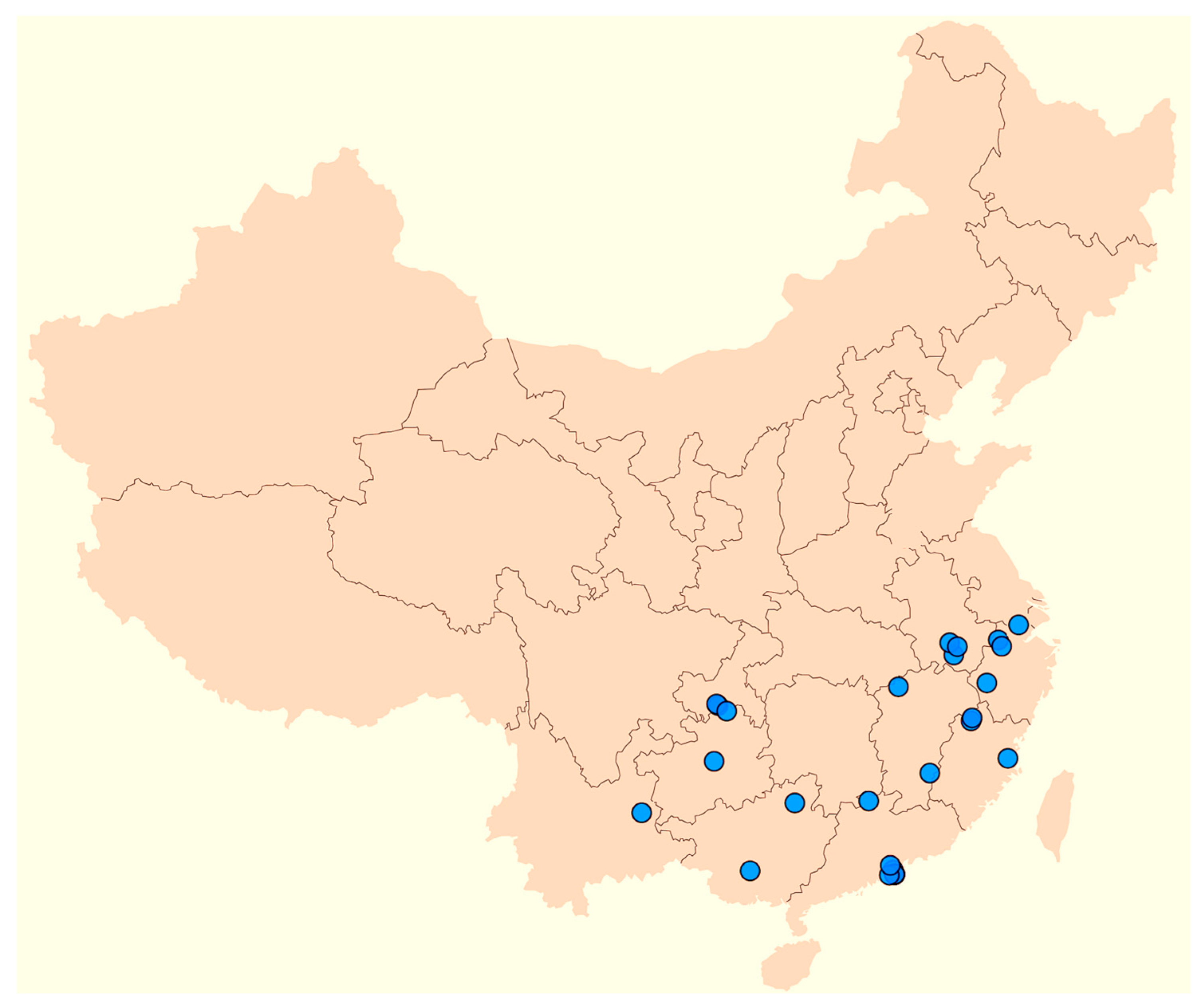

3.1.2. Portiodora speculatrix (Hance) M.B.Crespo, Mart.-Azorín & Mavrodiev comb. nov. [≡ Iris speculatrix Hance in J. Bot. 13: 196 (1875), Basionym]

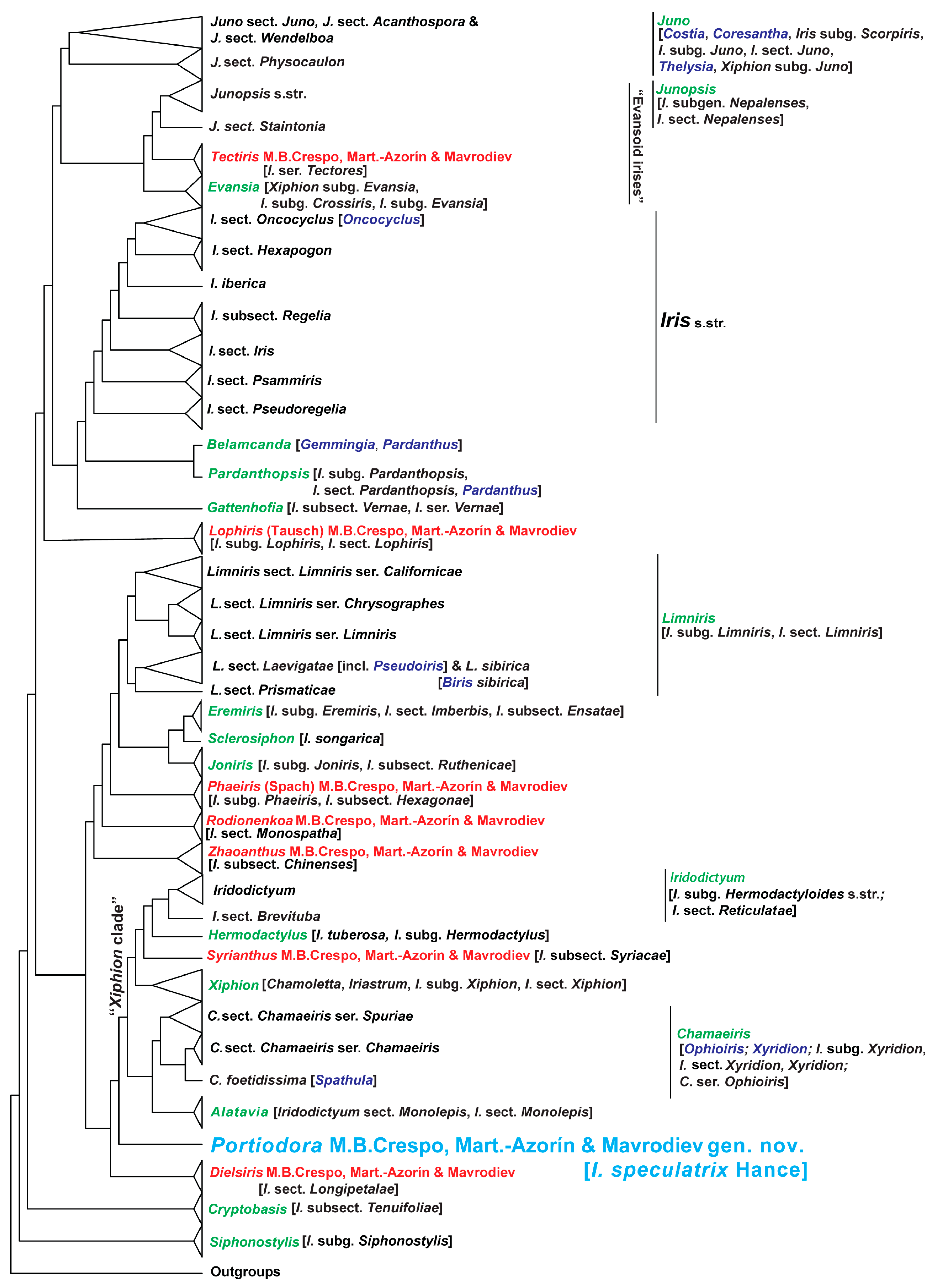

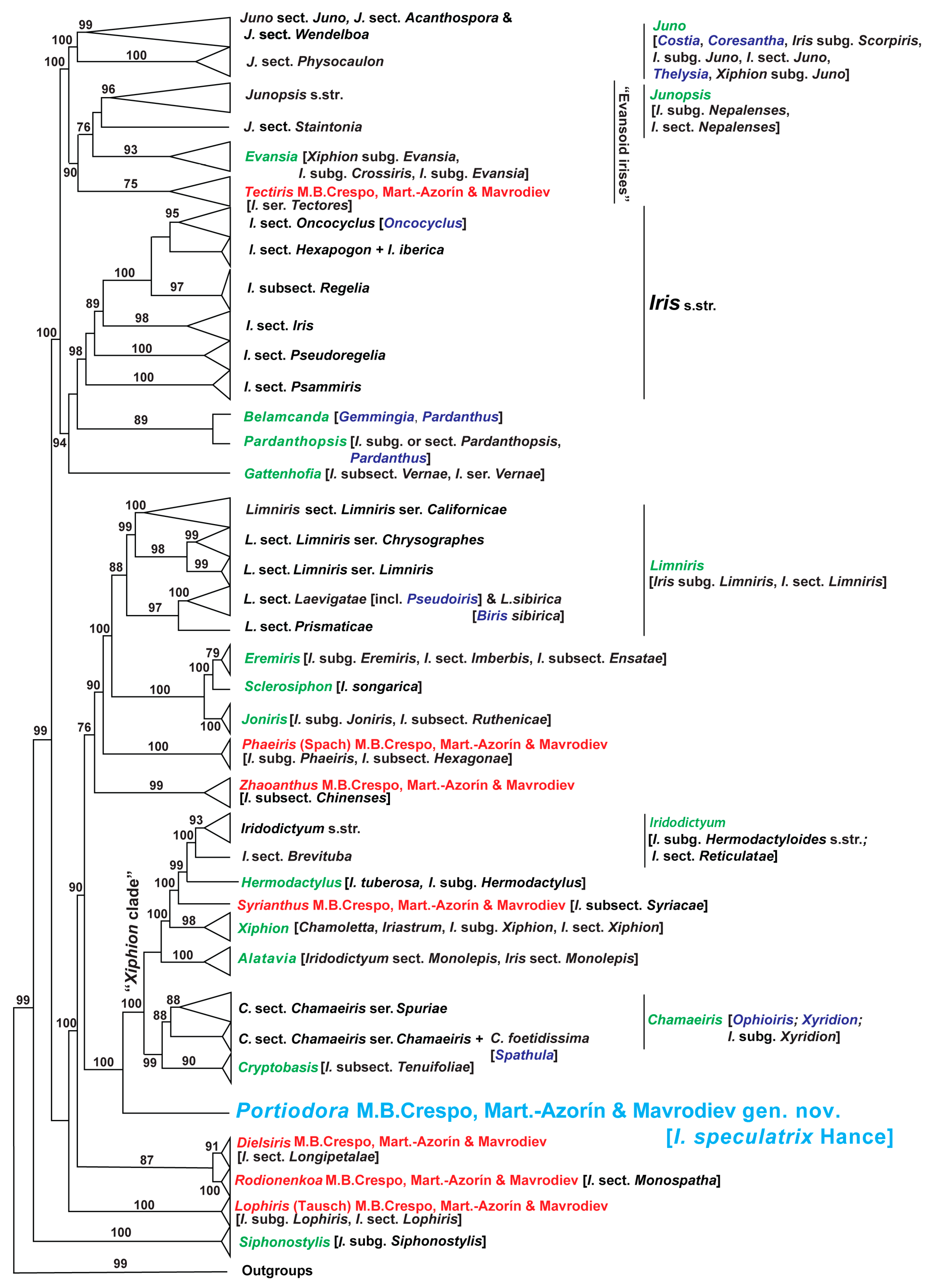

3.1.3. Comparative Molecular and Phylogenetic Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Relationships of Portiodora

4.2. Morphological Connections of Portiodora to Other Major Groups of Irises

4.3. Karyological Remarks

4.4. Ecological and Biogeographical Aspects

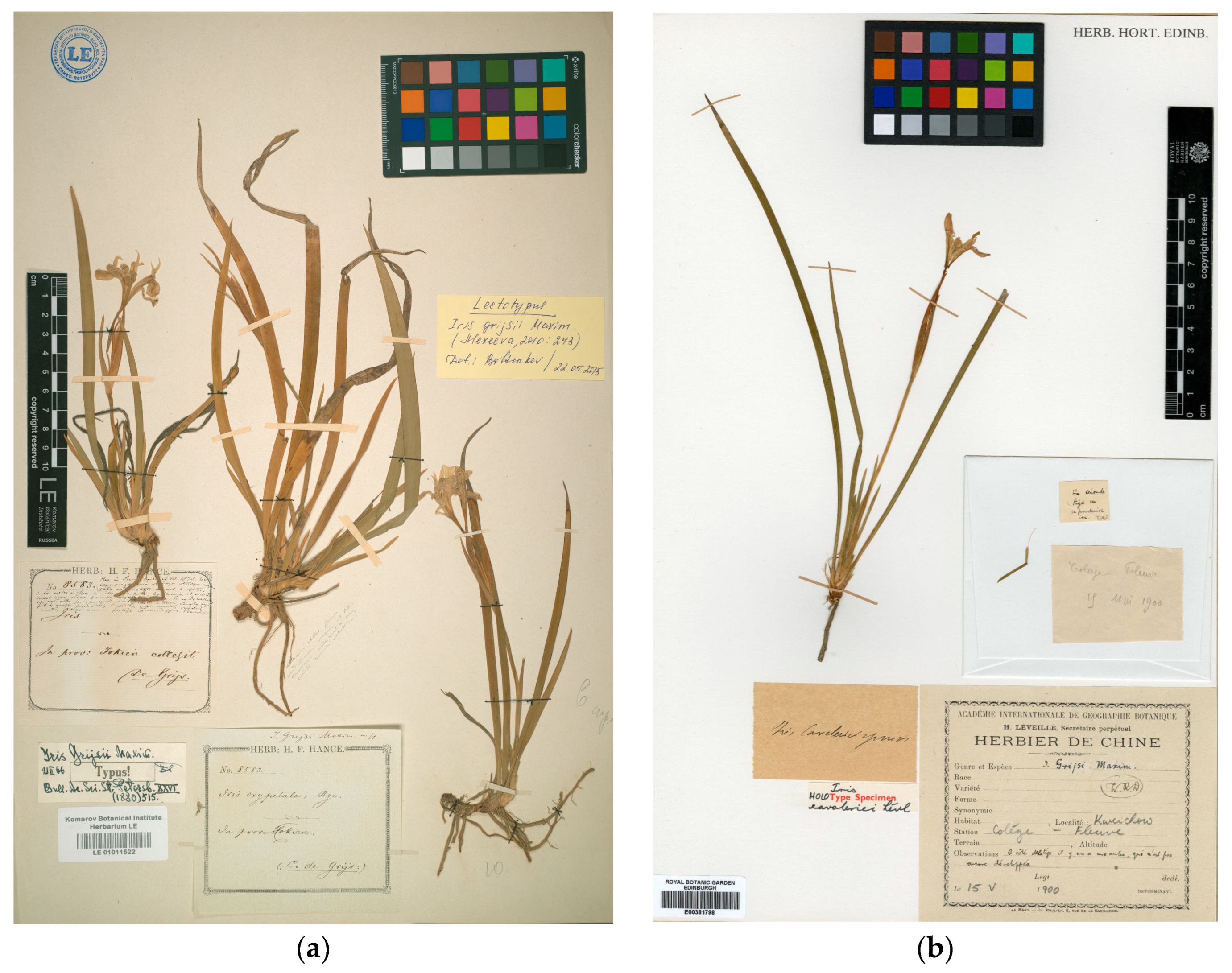

4.5. The Case of Iris grijsii., I. caveleriei and I. fujianensis

4.6. Some Reflections on the Current Vision on Iris-Segregated Genera

4.7. Implications on Biodiversity Conservation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Identification Key

- 1.

- Perigone segments all equal, free; style branches filiform, non-petaloid; capsule valves split down to base; seeds fleshy, blackish, globose, long persisting on the fruit axis (resembling a blackberry).......................................................Belamcanda

- −

- Perigone segments unequal (falls and standards), fused in a tube or rarely free; style branches flattened, petaloid; capsule and seeds with other characteristics.........2

- 2.

- Leaves bifacial (dorsiventrally flattened), usually canaliculate, sometimes polygonal in cross section.....................................................................................................3

- −

- Leaves isobilateral (laterally flattened), usually equitant........................................7

- 3.

- Roots fleshy, swollen, persistent; standards patent to reflexed; falls obovate, usually with a prominent central crest..............................................................................Juno

- −

- Roots fibrous, usually not fleshy neither swollen, deciduous; standards erect; falls panduriform, not crested or with a weak, inconspicuous crest......................4

- 4.

- Basal leaves quadrangular to octagonal in cross section; seeds appendiculate........5

- −

- Basal leaves semicircular to circular in cross section, sometimes with prominent ribs or keel; seeds not appendiculate.........................................................................6

- 5.

- Rootstock a bulb, with outer tunics reticulate, sometimes enclosing several offsets; standards conspicuous, longer than half the style branches length; ovary and capsule trilocular..................................................................................................Iridodictyum

- −

- Rootstock with 2–4 oblong tubercles, ±digitate; standards inconspicuous, shorter than half the style branches length; ovary and capsule unilocular....Hermodactylus

- 6.

- Bulb outer tunics reticulate. Leaves prominently ribbed on the outer side, sometimes keeled; stem inconspicuous, underground; stigma entire........................Alatavia

- −

- Bulb outer tunics membranous to somewhat fibrous, not reticulate. Leaves without prominent ribs on the outer side, not keeled; stem conspicuous, aerial; stigma bifid, usually with acute lobes.................................................................................Xiphion

- 7.

- Flowering stems with marked dichotomous branching pattern; flowers short-lived, shrivelling spirally and falling off just below the ovary; pedicels persistent, stiff after flower abscission; seeds winged.............................................Pardanthopsis

- −

- Flowering stems simple or without evident dichotomous branching pattern; flowers not shrivelling spirally, falling off just above the ovary; pedicels usually not stiff after flower abscission; seeds mostly unwinged, sometimes with fleshy cover or fleshy appendages......................................................................................................8

- 8.

- Both perigone whorls usually similar in size and shape; beard (a very conspicuous central row of thick pluricellular, multiseriate, clavate hairs) present on falls and sometimes also on standards; fruit opening by clefts, the valves remaining fused apically for a long time after dehiscence........................................................Iris

- −

- Both perigone whorls usually strongly differing in size and/or shape; beard absent, or falls sometimes crested, pubescent or with slender unicellular hairs; fruit valves splitting completely from the apex up to about the middle..................................9

- 9.

- Falls markedly crested, with 1–3 fringed, irregularly dissected or wavy rows......10

- −

- Falls uncrested or sometimes with an almost entire low crest or central ridge......14

- 10.

- Rhizome slender, long, heterogeneous, with cord-like branches at apex, swollen at nodes; leaves herbaceous, without prominent ribs; falls with crest of three fringed rows; seeds with a long, coiled appendage...............................................Lophiris

- −

- Rhizome lacking cord-like branches at the apex; leaves ± coriaceous, with 1–5 prominent ribs; falls with crest of a single fringed row, sometimes with lateral outgrowths; seeds lacking coiled appendages......................................................11

- 11.

- Fall crest mostly wavy; stigma oblong to triangular, entire; capsule beaked............................................................................................................Zhaoanthus

- −

- Fall crest fringed or dissected; stigma bilobed, with broad lobes; capsule ± pointed, not beaked.................................................................................................................12

- 12.

- Rootstock a small rhizome, with many swollen tuberous roots; perigone pieces entire or weakly erose-undulate on margins; fall crest not flanked with lateral pairs of outgrowths near the base............................................................Junopsis

- −

- Rootstock a thick rhizome, usually nodose and sometimes stoloniferous, lacking swollen, tuberous roots; perigone pieces markedly undulate-erose on margins; fall crest flanked with 2–3 lateral pairs of outgrowths near the base................13

- 13.

- Haft of the standards inconspicuous, short, nearly flat; capsule subcoriaceous; seeds brownish, matte, irregular in shape, angular, ±flattened..............Evansia

- −

- Haft of the standards conspicuous, long, canaliculate; capsule papery; seeds blackish, glossy, globose-pyriform, apiculate......................................................Tectiris

- 14.

- Stigma triangular or linguiform, entire or with crenate margins....................15

- −

- Stigma bilobed to bifid, sometimes with denticulate lobes..................................21

- 15.

- Style crests long triangular-lanceolate; capsule with a conspicuous long beak.....16

- −

- Style crests broadly triangular to roundish; capsule unbeaked or shortly beaked...18

- 16.

- Nectar drops at the base of falls; stamen filaments fused into a tube; seeds covered with glistening glands, lacking fleshy appendages........................Siphonostylis

- −

- Nectar drops lacking at the base of falls; stamen filaments not fused into a tube; seeds not glandulous, with a fleshy wing-like appendage..................................17

- 17.

- Leaves not glossy, lacking prominent ribs; stem short, hidden under spathes; perigone tube 25−65 mm long; falls with a central band of minute, velvety pubescence; capsule erect, short-beaked..........................................................Gattenhofia

- −

- Leaves glossy, prominently ribbed; stem elongated, clearly visible; perigone tube up to 8 mm long; falls smooth, not pubescent; capsule patent, long-beaked..Portiodora

- 18.

- Rhizome slender, long, heterogeneous, with cord-like branches at apex, swollen at nodes; leaves without prominent ribs; testa surface pitted..............Rodionenkoa

- −

- Rhizome lacking cord-like branches at apex; leaves usually with prominent ribs; testa surface not pitted...........................................................................................19

- 19.

- Leaves firm, coriaceous, up to 40 mm wide; seeds angular, discoid or semidiscoid, usually corky; testa surface smooth or papillate....................................Limniris

- −

- Leaves slender, up to 15 mm wide; seeds globose to pyriform, sometimes compressed, not corky; testa surface ± smooth, sometimes glossy..........................20

- 20.

- Rhizome slender, up to 5 mm in diameter; perigone tube up to 15 mm long; capsule globose to ovoid, 10–15 mm long; seeds with a fleshy appendage vanishing on drying......................................................................................................Joniris

- −

- Rhizome stout, up to 10 mm in diameter; perigone tube up to 3 mm long; capsule oblong-cylindrical to fusiform, 20–80 mm long; seeds lacking fleshy appendages..........................................................................................................Eremiris

- 21.

- Rhizome almost vertical; style crests lanceolate-triangular...........................22

- −

- Rhizome long, creeping; style crests broadly triangular, subquadrate (rarely narrowly triangular)..............................................................................................24

- 22.

- Rootstock with needle-like bristles at the apex; rhizome tough, nearly vertical, with compact, bulbiform, swollen leaf bases; shoots extra– or intravaginal; spathe valves 2; perigone tube up to 2 cm long; capsule unbeaked; seeds tuberculate, necked...................................................................................................Syrianthus

- −

- Rootstock covered with brownish remains of leaf sheaths, not spiny; leaves not bulbiform at the base; plants forming dense tussocks, with all shoots intravaginal; spathe valves 3–4; perigone tube 4–12 cm long; capsule beaked; seeds wrinkled, unnecked........................................................................................23

- 23.

- Stems absent or hidden among leaf remains; perigone tube scapiform; crest triangular-lanceolate to oblong-lanceolate, irregularly fringed on margins; capsule 6-ribbed, not reticulate-nerved...........................................Cryptobasis

- −

- Stems distinct; perigone tube not scapiform; crests narrowly triangular-lanceolate to linear, with slightly crenate to almost entire margins; capsule, trigonous, reticulate-nerved..................................................................................Sclerosiphon

- 24.

- Haft of falls patent, without a central ridge; capsule conspicuously beaked; seed testa fleshy and smooth or loose-papery with irregularly ridged surface........Chamaeiris

- −

- Hafts of falls erect, with a central ridge; capsule with rounded to acute apex, rarely with a short beak; seed testa corky or hard, with wrinkled or smooth surface.....25

- 25.

- Falls glabrous; capsule rounded in cross section; seeds nearly globular, with testa wrinkled...........................................................................................Dielsiris

- −

- Falls pubescent on or aside ridge; capsule ± hexagonal in cross section; seeds semidiscoid to discoid, flattened, ±angular, with testa corky, ±smooth.....Phaeiris

References

- Goldblatt, P.; Manning, J.C.; Rudall, P. Iridaceae. In The Families and Genera of Flowering Plants; Kubitzki, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 3, pp. 295–333. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo, M.B.; Herrero, A.; Quintanar, A. Iridaceae. In Flora Iberica; Rico, E., Crespo, M.B., Quintanar, A., Herrero, A., Aedo, C., Eds.; Real Jardín Botánico, CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Volume 20, pp. 400–491. [Google Scholar]

- Crișan, I.; Cantor, M. New perspectives on medicinal properties and uses of Iris sp. Hop Med. Plants 2016, 24, 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E. Introgressive Hybridization; John Wiley & Sons Inc. in Association with Chapman and Hall: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1949; pp. 1–109. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, M.L.; Ballerini, E.S.; Brothers, A.N. Hybrid fitness, adaptation and evolutionary diversification: Lessons learned from Louisiana irises. Heredity 2012, 108, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrodiev, E.V.; Gómez, J.P.; Mavrodiev, N.E.; Melton, A.E.; Martínez-Azorín, M.; Crespo, M.B.; Robinson, S.K.; Steadman, D.W. On biodiversity and conservation of the Iris hexagona complex (Phaeiris, Iridaceae). Ecosphere 2021, 12, e03331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykes, W.R. The Genus Iris; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1912; pp. 1–245, 48 pls. [Google Scholar]

- SGBIS—Species Group of the British Iris Society (Ed.) A Guide to Species Irises: Their Identification and Cultivation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; pp. 172–195. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, B.; Weiss-Schneeweiss, H.; Temsch, E.M.; So, S.; Myeong, H.-H.; Jang, T.-S. Genome Size and Chromosome Number Evolution in Korean Iris L. Species (Iridaceae Juss.). Plants 2020, 9, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapir, Y.; Shmida, A.V.I. Species concepts and ecogeographical divergence of Oncocyclus irises. Israel J. Plant Sci. 2002, 50, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Samad, N.; Bou Dagher-Kharrat, M.; Hidalgo, O.; El Zein, R.; Douaihy, B.; Siljak-Yakovlev, S. Unlocking the karyological and cytogenetic diversity of Iris from Lebanon: Oncocyclus section shows a distinctive profile and relative stasis during its continental radiation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldblatt, P.; Takei, M. Chromosome cytology of Iridaceae—Patterns of variation, determination of ancestral base numbers, and modes of karyotype change. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1997, 84, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, M.B.; Martínez-Azorín, M.; Mavrodiev, E.V. Can a rainbow consist of a single colour? A new comprehensive generic arrangement of the ‘Iris sensu latissimo’ clade (Iridaceae), congruent with morphology and molecular data. Phytotaxa 2015, 232, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrodiev, E.V.; Martínez-Azorín, M.; Dranishnikov, P.; Crespo, M.B. At least 23 genera instead of one: The case of Iris L. s.l. (Iridaceae). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillie, N.; Chase, M.W.; Hall, T. Molecular studies in the genus Iris L.: A preliminary study. Ann. Bot. 2001, 58, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C.A. Phylogeny of Iris based on chloroplast matK gene and trnK intron sequence data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2004, 33, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.A. Subgeneric classification in Iris re-examined using chloroplast sequence data. Taxon 2011, 60, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, M.B.; Martínez-Azorín, M.; Mavrodiev, E.V. “Reticulata irises”: A nomenclatural and taxonomic synopsis of the genera Alatavia and Iridodictyum (Iris subg. Hermodactyloides auct., Iridaceae). Plant Biosyst. 2024, 158, 763–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hance, H.F. Exiguitates carpologicae. J. Bot. 1870, 8, 312–314. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J.G. Iris speculatrix. Native of Hong-Kong. Curtis’s Bot. Mag. 1877. ser. 3, 33, Table 6306. Available online: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/203318#page/158/mode/1up (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Zhao, Y.T.; Noltie, H.J.; Mathew, B.F. Iridaceae. In Flora of China; Flora of China Editorial Committee, Ed.; MBG Press & Science Press: Beijing, China; St. Louis, MO, USA, 2000; Volume 24, pp. 297–313. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Q.M.; Wu, T.L.; Xia, N.H.; Xing, F.W.; Lai, P.C.C.; Yip, K.L. Rare and Precious Plants of Hong Kong; Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region: Hong Kong, China, 2003; pp. 1–234. [Google Scholar]

- Siu, T.-Y.; Wong, K.-H.; Kong, B.L.-H.; Wu, H.-Y.; But, G.W.-C.; Shaw, P.-C.; Lau, D.T.-W. The complete chloroplast genome of Iris speculatrix Hance, a rare and endangered plant native to Hong Kong. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2022, 7, 864–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IUCN. IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria: Version 3.1; IUCN Species Survival Commission, IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, B. The Iris, 2nd ed.; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1989; pp. 1–215. [Google Scholar]

- Waddick, J.W.; Zhao, Y.-T. Iris of China; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1992; pp. 1–192. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J.G. Handbook of Irideae; G. Bell & Sons: London, UK, 1892; pp. 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Wilson, C.A. Molecular phylogeny of crested Iris based on five plastid markers (Iridaceae). Syst. Bot. 2013, 38, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.; Tillie, N.; Chase, M.W. A re-evaluation of the bulbous irises. Ann. Bot. 2001, 58, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, T.-Y.; Lee, S.-R. Complete plastid genome of Iris orchioides and comparative analysis with 19 Iris plastomes. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiers, B. Index Herbariorum: A Global Directory of Public Herbaria and Associated Staff (Continuously Updated). Available online: http://sweetgum.nybg.org/ih/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Turland, N.J.; Wiersema, J.H.; Barrie, F.R.; Gandhi, K.N.; Gravendyck, J.; Greuter, W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Herendeen, P.S.; Klopper, R.R.; Knapp, S.; et al. International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants (Madrid Code); Regnum Veg. 162.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.iaptglobal.org/_functions/code/madrid (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Li, D.-Z.; Gao, L.-M.; Li, H.-T.; Wang, H.; Ge, X.-J.; Liu, J.-Q.; Chen, Z.-D.; Zhou, S.-L.; Chen, S.-L.; Yang, J.B.; et al. Comparative analysis of a large dataset indicates that internal transcribed spacer (ITS) should be incorporated into the core barcode for seed plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 19641–19646. [Google Scholar]

- Snoad, B. Chromosome counts of species and varieties of garden plants. JIHI Ann. Rep. 1952, 42, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lenz, W.L. Iris tenuis, S. Wats., a new transfer to the subsection Evansia. Aliso 1959, 4, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimphamba, B.B. Cytogenetic studies in the genus Iris: Subsection Evansia Benth. Cytologia 1973, 38, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.Q.; Xue, X.J. Chromosome numbers of thirteen iridaceous species from Zhejiang Province. Acta Agric. Univ. Zhejiang 1986, 12, 99–101. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Wang, G.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J. Floral syndrome and breeding characters of Iris speculatrix. Acta Agric. Univ. Zhejiang 2014, 26, 1218–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.-P.; Li, K.; Xia, Y. Green period characteristics and foliar cold tolerance in 12 Iris species and cultivars in the Yangtze Delta, China. HortTechnology 2017, 27, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.A. Two new species in Iris series Chinenses (Iridaceae) from south-central China. PhytoKeys 2020, 161, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murrain, J. Iris speculatrix: Girls Who Wear Glasses. SIGNA 2012, 87, 4214–4215. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett, V.H.C. A white variety of Iris speculatrix Hance. Sunyatsenia 1937, 3, 265. [Google Scholar]

- Waddick, J.W. (Kansas City, MO, USA); Murrain, J. (Kansas City, MO, USA). Personal communication, 2024.

- Hall, T. Relationships within genus Iris, with special reference to more unusual species grown at Kew. CIS Newsl. 2013, 57, 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rodionenko, G.I. The Genus Iris L. (Questions of Morphology, Biology, Evolution and Systematics); British Iris Society of London, Translator; V.L. Komarov Botanical Institute, Academy of Sciences of the USRR: Leningrad, Russia, 1961; pp. 1–222. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Westerkamp, C.; Claßen-Bockhoff, R. Bilabiate flowers: The ultimate response to bees? Ann. Bot. 2007, 100, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. Micromorphology and anatomy of crested sepals in Iris (Iridaceae). Int. J. Plant Sci. 2015, 176, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. Mechanisms for the evolution of complex and diversely elaborated sepals in Iris identified by comparative analysis of developmental sequences. Am. J. Bot. 2015, 102, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.H.; Park, Y.W.; Yoon, P.S.; Choi, H.W.; Bang, J.W. Karyotype analysis of eight Korean native species in the genus Iris. Korean J. Med. Crop Sci. 2004, 12, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, E.; Pastor, J. Contribución al estudio cariológico de la familia Iridaceae en Andalucía Occidental. Lagascalia 1994, 17, 257–272. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, V.; Sadat-Hosseini Grouh, M.; Solymani, A.; Bahermand, N.; Meftahizade, H. Assessment of cytological and morphological variation among Iranian native Iris species. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 8805–8815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, L.F.; Mitra, J.; Nelson, I.S. Cytotaxonomic studies of Louisiana irises. Bot. Gaz. 1961, 123, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexeeva, N.B. Iris grijsii Maxim. In Catalogue of the Type Specimens of East-Asian Vascular Plants in the Herbarium of the V.L. Komarov Botanical Institute (LE), Part 2 (China); Gabrovskaya-Borodina, A.E., Ed.; KMK Scientific Press: Moscow/St. Petersburg, Russia, 2010; p. 243. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Maximowicz, C.J. Diagnoses plantarum novarum asiaticarum, III. Bull. Acad. Imp. Sci. Saint-Pétersbourg 1880, 26, 420–542. [Google Scholar]

- Léveillé, H. Liliacées, Amaryllidacées, Iridacées et Hémodoracées de Chine. Mem. Pontif. Accad. Romana Nuovi Lincei 1905, 23, 333–378, [Reprinted in a 50-page booklet by Tipografia della Pace di F. Cuggiani, Roma]. [Google Scholar]

- Su, X.X. A New Species of Iridaceae from Fujian Province—Iris fujianensis. J. Fujian For. Sci. Tech. 2024, 51, 101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Lazkov, G.A.; Sennikov, A.N.; Koichubekova, G.A.; Naumenko, A.N. Taxonomic corrections and new records in vascular plants of Kyrgyzstan, 3. Memoranda Soc. Fauna Fl. Fenn. 2014, 90, 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Goldblatt, P.; Manning, J.C. The Iris Family. Natural History and Classification; Timber Press Inc.: London, UK, 2008; pp. 1–290. [Google Scholar]

- Speta, F. Hyacinthaceae. In The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants; Kubitzki, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; Volume 3, pp. 261–285. [Google Scholar]

- Speta, F. Systematische Analyse der Gattung Scilla L. s.l. (Hyacinthaceae). Phyton 1998, 38, 1–141. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Azorín, M.; Crespo, M.B.; Juan, A.; Fay, M.F. Molecular phylogenetics of subfamily Ornithogaloideae (Hyacinthaceae) based on nuclear and plastid DNA regions, including a new taxonomic arrangement. Ann. Bot. 2011, 107, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Azorín, M.; Crespo, M.B.; Alonso, M.Á.; Pinter, M.; Crouch, N.R.; Dold, A.P.; Mucina, L.; Pfosser, M.; Wetschnig, W. Molecular phylogenetics of subfamily Urgineoideae (Hyacinthaceae): Toward a coherent generic circumscription informed by molecular, morphological, and distributional data. J. Syst. Evol. 2023, 63, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Azorín, M.; Crespo, M.B.; Alonso, M.Á.; Pinter, M.; Crouch, N.R.; Dold, A.P.; Mucina, L.; Pfosser, M.; Wetschnig, W. A generic monograph of the Hyacinthaceae subfam. Urgineoideae. Phytotaxa 2023, 610, 1–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.M.; Ebach, M.C. Cladistics: A Guide to Biological Classification, 3rd ed.; Systematics Association Special Volume Series; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; Volume 88, pp. 1–446. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | Portiodora | Zhaoanthus | Eremiris | Joniris | Cryptobasis | Syrianthus | Chamaeiris |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhizome | Stout, nodose, creeping | Slender, wiry, stoloniferous, many-branched | Thick, compact, creeping, branched | Slender, many-branched, creeping | Slender, nodose, vertical | Stout, nodose, nearly vertical | Stout, nodose, creeping |

| Stems | Long, visible | Long, visible, simple | Long, visible, simple | Short, slender, simple | Hidden among leaf remains | Long, visible, simple | Long, visible, simple to few-branched |

| Keel of spathe valves | Absent | Present | Present | Absent | Present | Present | Present |

| Perigone tube shape and length | Cylindric, 5–8 mm long | Cylindric, 1–70 mm long | Cup-like, 1–3 mm long | Cylindric, 5–15 mm long | Cylindric, 40–120 mm long, scapiform | Cylindric, up to 20 mm long | Cup-like,2–27 mm long |

| Outline of falls | Obovate-spatulate | Spatulate | Oblanceolate | Broadly oblanceolate | Panduriform to spatulate | Oblanceolate to panduriform | Panduriform or subspatulate |

| Fall position | Erect-patent | Erect-patent | Erect-patent | Erect-patent | Erect-patent to patent | Erect to erect-patent | Patent |

| Style branches length | Slightly shorter than falls | Half the length of falls | About half the length of falls | About half the length of falls | Slightly shorter than falls | Slightly shorter than falls | About half the length of falls |

| Crest of falls | Low sinuous near the middle, no lateral outgrowths | Low, wavy, with lateral outgrowths | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Stigmatic lip | Entire, triangular-obtuse | Entire, oblong to triangular | Triangular, long acuminate | Triangular, apiculate | Bilobed, with rounded lobes | Bilobed, with rounded lobes | Bifid, with acute lobes |

| Capsule shape | Oblong-fusiform, subtrigonous | Ellipsoid to subglobose, trigonous | Oblong-cylindrical to fusiform, trigonous, | Globose to obovoid, trigonous | Ovoid to cylindric, not trigonous | Cylindricalellipsoid, trigonous | Ovate-lanceolate to oblong, not trigonous |

| Capsule position regarding stem and spathes | Patent, long exerted | Erect, often exerted | Erect, often exerted | Erect, hidden into spathes | Erect, often exerted | Erect, often exerted | Erect, often exerted |

| Capsule ribs | 3, prominent | 3, prominent | 6, weak | 6, weak | 6, prominent | 6, weak | 6, prominent |

| Capsule beak | Present | Present | Present | Absent | Present | Absent | Present |

| Capsule dehiscence | From apex to base | From apex to about middle | From apex to about middle | From apex to about middle | From apex to about middle | From apex to about middle | From apex to about middle |

| Capsule valves | Curled backwards | Erect to erect-patent | Erect to erect-patent | Curled backwards | Erect to erect-patent | Erect to erect-patent | Erect to curled backwards |

| Seed morphology | Globose-angulose | Globose compressed | Pyriform, subapiculate | Globose to pyriform | Angulose to subcubic | Globose, necked | Globose to subcubic |

| Seed appendages | Aril, withering as a wing | Fleshy raphe | Absent | Fleshy raphe, vanishing | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Seed testa | Rugulose | Slightly wrinkled. | Smooth, shiny | Smooth | Wrinkled on faces, smooth on back | Tuberculate, hard | Fleshy and smooth or loose-papery |

| Genus | Chromosomal Size Structure | Satellited Chromosomes | Secondary Constrictions | Telocentric and/or Subtelocentric Chromosomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portiodora | Homogeneous | 1 pair | Absent | Absent |

| Chamaeiris | Heterogeneous | 0 | Absent | Absent |

| Zhaoanthus | Heterogeneous | 0 | Absent | Present |

| Rodionenkoa | Heterogeneous | 1 pair | Absent | Present |

| Phaeiris | Heterogeneous | 2–3 pairs | Present | Present |

| Joniris | Subhomogeneous | 1 pair | Absent | Absent |

| Eremiris | Subhomogeneous | 1 pair | Absent | Present |

| Lophiris | Heterogeneous | 1–2 pairs | Absent | Absent |

| Evansia | Heterogeneous | (0–)2 pairs | Absent/present | Present |

| Tectiris | Heterogeneous | (0–)2 pairs | Absent/present | Absent |

| Iris | Heterogeneous | 0–1 pair | Absent/present | Present |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crespo, M.B.; Martínez-Azorín, M.; Mavrodiev, E.V. Watching the South China Sea—Portiodora (Iridaceae), a New Genus for Iris speculatrix Based on Comprehensive Evidence: The Contribution of Taxonomic Resolution to Biodiversity Conservation. Biology 2025, 14, 1767. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121767

Crespo MB, Martínez-Azorín M, Mavrodiev EV. Watching the South China Sea—Portiodora (Iridaceae), a New Genus for Iris speculatrix Based on Comprehensive Evidence: The Contribution of Taxonomic Resolution to Biodiversity Conservation. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1767. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121767

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrespo, Manuel B., Mario Martínez-Azorín, and Evgeny V. Mavrodiev. 2025. "Watching the South China Sea—Portiodora (Iridaceae), a New Genus for Iris speculatrix Based on Comprehensive Evidence: The Contribution of Taxonomic Resolution to Biodiversity Conservation" Biology 14, no. 12: 1767. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121767

APA StyleCrespo, M. B., Martínez-Azorín, M., & Mavrodiev, E. V. (2025). Watching the South China Sea—Portiodora (Iridaceae), a New Genus for Iris speculatrix Based on Comprehensive Evidence: The Contribution of Taxonomic Resolution to Biodiversity Conservation. Biology, 14(12), 1767. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121767