1. Introduction

With the rapid development of sequencing technologies and high-throughput biomedical platforms has enabled the generation of increasingly comprehensive omics datasets, revolutionizing our ability to investigate biological systems [

1]. By integrating these diverse data sources, researchers can perform deeper analyses that improve clinical decision making and advance disease treatment outcomes [

2]. Consequently, numerous machine learning-based methods have been proposed for multi-omics data integration [

3,

4].

The integration of omics data can be broadly categorized into supervised and unsupervised approaches [

5]. Unsupervised methods typically map multi-omics data into a unified low-dimensional space for clustering, as seen in multi-view clustering with low-rank and sparsity constraints [

6] and decoupled contrastive clustering [

7]. However, the scarcity of annotated labels limits their biological interpretability, motivating the adoption of supervised approaches. For example, the group-regularized ridge regression method has been proposed to adaptively integrate co-data by adjusting penalty intensities across variable groups [

8]. Similarly, using latent components for data integration has led to sparse generalized canonical correlation analysis, which discriminates phenotypic groups and identifies shared information across omics modalities [

9]. Recently, dynamic fusion frameworks such as Multi-Modality Dynamics (MMDynamic) have been introduced to improve both performance and trustworthiness by adaptively weighting informative features and modalities for each sample [

10]. Despite these advancements, many of these methods rely on simplified linear assumptions that cannot fully capture the nonlinear complexities inherent in biomedical data.

Deep learning has emerged as a powerful solution for multi-omics integration due to its ability to model nonlinear relationships and learn modality-specific representations [

11,

12]. To reconstruct multi-omics data using such representation, Chen Zhao et al. proposed CLCLSA (Cross-omics Linked unified embedding with Contrastive Learning and Self Attention), a deep learning multi-omics integration framework [

13]. In parallel, graph-based representation learning methods have demonstrated great potential in bioinformatics, as many biomedical entities and their interactions can be naturally encoded as graphs [

14,

15,

16]. Graph Neural Networks and their variants utilize relational structures to model interactions among biomolecules, patients, or clinical variables, thereby improving both predictive performance and interpretability. For instance, MOGONET [

17] integrates within-omics features using Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) [

18] and employs correlation discovery for cross-omics integration. Similarly, MOSGAT [

19] incorporates specificity-aware graph attention and cross-modal learning based on Graph Attention Networks (GATs), which enhances disease diagnosis through adaptive attention weighting and inter-omics feature discovery. These advances highlight the versatility and potential of graph-based frameworks, along with applications such as circRNA drug resistance prediction [

20,

21]. Moreover, attention mechanisms further strengthen feature fusion by allowing models to selectively focus on the most informative signals [

22].

Despite these advances, several key challenges remain. Effective integration of multi-omics data requires extracting sample-specific features within each omics data while simultaneously identifying cross-omics correlations. Existing methods often fall to dynamically capture the varying information across omics for different samples, which undermines interpretability and limits the reliability of identified biomarkers [

23]. Additionally, prior research has largely overlooked latent correlations within omics data, intuitively, data with similar structures should yield similar representations.

To address these challenges, we propose MOGOLA (Multi-Omics integration by Gating and Omics-Linked Attention), a novel framework for multi-omics integration and biomarker discovery. For each omics dataset, cosine similarity is computed between inter-omics samples, followed by the construction of a similarity matrix using a K-nearest-neighbors strategy with threshold-based filtering. Both the similarity matrix and the raw omics data are processed using graph structure learning modules. By combining the strengths of Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) and Graph Attention Networks (GATs), MOGOLA introduces gating and confidence mechanisms to enhance cross-omics feature selection. Furthermore, a novel cross-omics attention mechanism is incorporated to implicitly capture latent inter-omics correlations, thereby optimizing the fusion process and improving the identification of disease-associated biomarkers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of MOGOLA

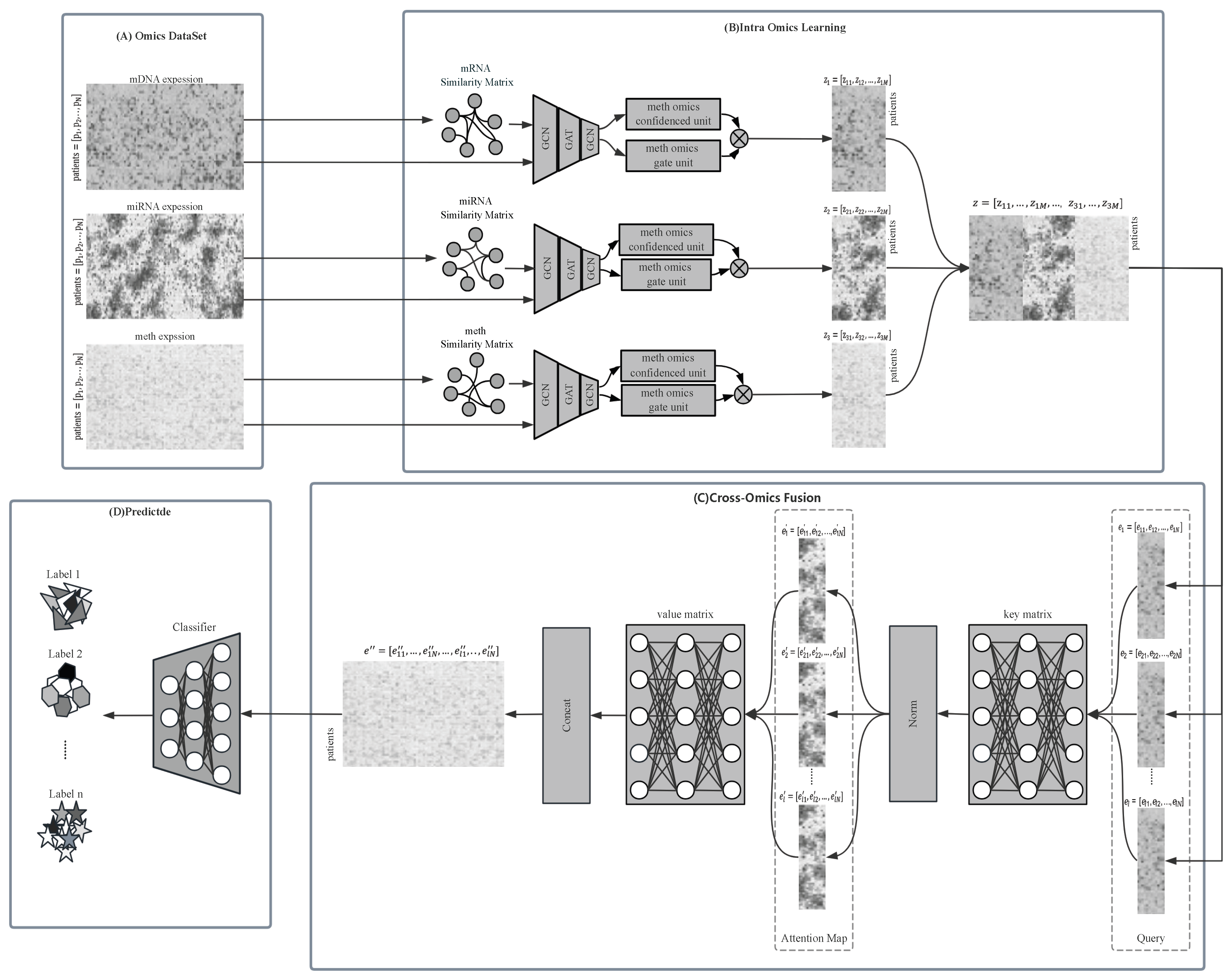

MOGOLA is a two-stage framework designed to effectively learn from multi-omics information and capture its relationship with the ground-truth labels. As shown in

Figure 1, the framework comprises two main components: Inter-Omics Learning and Cross-Omics Fusion.

In the Inter-Omics Learning stage, MOGOLA constructs omics specific graph structures to model sample relationships within each omics type. A confidence-weighted gating mechanism adaptively refines feature interactions across omics. In the Cross-Omics Fusion stage, an omics-linked attention mechanism integrates the heterogeneous omics representations obtained from each omics, allowing the model to focus on highly informative and complementary features across modalities. Detailed description of each component are provided in the subsequent sections.

2.2. Inter-Omics Learning

2.2.1. Sample Similarity Matrix Construction

Constructing an accurate sample similarity matrix serves as the fundamental step for building the graph structure in MOGOLA. For each omics data, samples were first represented as feature vector, and pairwise similarity was quantified using cosine similarity. Given two samples

i and

j from the

m-th omics, the cosine similarity is computed as follows:

where

and

denote the

m-th omics feature vectors of nodes

i and node

j, “·” represents the dot product operation, and “

” denotes the Euclidean norm.

To construct a sparse and meaningful graph, a K-Nearest-Neighbors (KNN) [

24] strategy was applied based on these similarity values. For each sample, cosine similarities were sorted in descending order, and the top

k Nearest Neighbors were retained as connected edges. The resulting sample similarity matrix for the

m-th omics is defined as follows:

where

denotes the binary similarity matrix corresponding to the

m-th omics data, and

k controls the sparsity level. All non-neighboring pairs are assigned zero similarity. This KNN-based matrix construction ensures that each graph maintains local structural information while filtering out weak or noisy relationships.

2.2.2. Graph Structure Learning Module

To capture complex relationships with each omics, MOGOLA employs a graph structure learning module that integrates Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) [

18] and the Graph Attention Network (GAT) [

19]. This hybrid design extracts both local structural information, producing refined latent features.

The GCN layer aggregates features based on the similarity matrix

and generates low-dimensional embedding. Given omics data

and similarity matrix

, the GCN propagation rule is

where

is a diagonal matrix of

,

is the identity matrix, adding self-loops to the

.

is a learnable weight matrix, and

is a nonlinear activation function. Through iterative message passing, nodes aggregate information from their neighbors to obtained enriched feature representations.

To overcome the limitations of uniform neighborhood aggregation in GCN, GAT assigns different weights to neighboring nodes via a self-attention mechanism. The GAT layer computes node embeddings as follows:

where

is a learnable weight matrix, and

denotes the set of neighbors of node

i. The term

represents the attention coefficient between node

i and node

j in the

m-th omics, which is computed as follows:

where

a denotes the learnable attention vector,

represents the Leaky Relu activation function, and

indicates the concatenation operation applied to the transformed node features. Using the attention weights

, GAT performs a weighted aggregation of the features from neighborhood nodes to obtain refined latent representation. By introducing dynamic, data-driven node relationship through attention mechanism, GAT enhances feature learning and captures the underlying graph structures.

To integrate the structural advantages of GCN with the adaptive learning capability of GAT, our module combines GCN’s structural stability with GAT’s dynamic attention mechanism. GCN aggregates information from fixed neighborhoods to capture local topological features and preserve graph stability, whereas GAT uses learnable attention weights to selectively emphasize informative neighbors, thereby enhancing global semantic relationships. Specifically, to address the common issues of over-smoothing in deep architectures and insufficient pattern extraction in shallow network, we adopt a three-layer design. The first GCN layer aggregates structured neighborhoods to capture high level topological features and establish a foundational embedding. The intermediate GAT layer then adaptively re-weights neighborhood contributions, suppressing noise while preserving salient features. The output was subsequently passed to a final GCN layer, which further consolidates the refined neighborhood information into the final latent representation. The hybrid representation learning process for the

m-th omics is defined as follows:

where

,

, and

denote the

m-th omics latent feature matrix, respectively. Alternating GCN and GAT layers enable the model to preserve graph structural consistency while adaptively enhancing biological marker aggregation.

During this stage, a separate similarity matrix and graph structure are constructed for each omics data. Each graph structure processes only its corresponding omics data, thereby preserving modality-specific characteristics and preventing cross-omics interference.

2.2.3. Gating and Confidence Learning Mechanism

High-dimensional data often contain heterogeneous noise and variable feature relevance across modalities, which may degrade classification performance. To address these challenges, MOGOLA employs a gating mechanism for adaptive feature selection and a True-Class Probability (TCP) [

25] technique to estimate the reliability of each omics data.

Given the latent embedding

, a linear projection

, followed by a nonlinear activation function, produces an intermediate representations. A gating function

was then applied to derive the gated features:

where

represents the gating feature matrix for the

m-th omics,

is the sigmoid activation function, and ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication.

To further regulate the contribution of each omics, a TCP-based confidence mechanism is introduced. TCP evaluates the probability assigned to the true class for each sample, reducing confidence when misclassification occurs and thus reflecting uncertainty in the corresponding omics. These confidence scores are then incorporated as adaptive weights to prioritize more reliable modalities during fusion.

Specifically, we define a linear layer

t() to compute the confidence score through encoding the

into a vector, from which the TCP weighted matrix

is obtained as follows:

The final latent representation

for

m-th omics was obtained by combining gating-based and confidence-based refinements:

During the inter-omics learning stage, the graph structure learning module extracts latent structure features, while the gating and confidence mechanisms refine and adaptively weigh these representations. Together, these components enable MOGOLA to capture modality-specific patterns, suppress noise, and enhance discriminative learning across heterogeneous omics datasets.

2.3. Omics-Linked Attention for Cross-Omics Fusion

Based on the previously obtained latent representations for each omics, we introduce the Omics-Linked Attention (OLA) mechanism [

26] to achieve cross-omics feature fusion and final prediction. Unlike traditional self-attention, which only considers single-omics samples and incurs high computational complexity, OLA captures cross-omics relationships by computing attention across different omics data.

Specifically, before computing OLA, the omics features

are concatenated to form a combined omics feature matrix

. For the

i-th node in

, its similarity with the

j-th row of the omics link unit matrix

is used to compute the attention score matrix

, as follows:

where

is a learnable weight matrix that serves as a memory of the entire training dataset, calculating similarity with input features to generate the attention map

. This attention map represents the similarity between the

i-th node of

and the

j-th row of

. To eliminate sensitivity to input scale, the output is normalized twice-first across columns using softmax, then across rows using L1-normalization, which is formulated as

where

and

are separately normalized columns and rows.

Each normalization has a computational complexity of

, where

N is the number of nodes, ensuring minimal overhead and preserving scalability even for large graphs. Finally, the features are updated based on the attention scores in

, producing the output

:

where

reconstructs the output by transforming the attention map

into enhanced features using optimized prototypes from the entire dataset. As described above, the complete calculation of OLA can be expressed as

During multi-head attention computation, conventional self-attention splits input features into several blocks, computes attention independently within each block, and then concatenates the results. While this reduces computation and memory usage, it may degrade performance. In contrast, OLA allows all tokens to interact via omics link

and

, improving performance while reducing the amount of parameter. Multi-head OLA is implemented as follows:

where

divided input features into several blocks,

and

denotes the

e-th feature block and attention head, respectively, and

H is the total number of heads.

and

correspond to different heads, and

is a transformation matrix ensuring consistency between the input and output feature dimensions. The resulting

is a feature matrix weighted by OLA.

Compared with standard self-attention, OLA is more concise and computationally efficient, enhancing model performance while significantly reducing parameter count. The fused multi-omics feature matrix is subsequently passed through a fully connected layer, whose output serves as the final prediction of the model.

2.4. Model Optimization

To improve the model performance and training stability, MOGOLA adopts a two-step learning strategy. The first stage focuses on optimizing the omics-specific graph structures, while the second stage jointly optimizes the entire network, including the gating and confidence modules.

2.4.1. Graph Structure Optimization

In this stage, the latent features generated by the graph structure learning module are fed into a classifier to predict sample labels. The model is trained using a supervised loss function defined as

where

denotes the true label of the

n-th sample, and

represents the predicted probability that the

n-th sample feature in the

m-th omics belongs to class

q. The terms

M and

N indicate the number of omics type and the number of samples. In addition, class-specific loss weights are incorporated to address label imbalance in the training set.

2.4.2. Gating and Confidence Learning Optimization

In the second stage, we optimize the gating and confidence module by minimizing the loss functions corresponding to their respective tasks.

First, given the latent omics representation

, the classifier

followed by a

operator produces a confidence-based predictive distribution:

where

is the predicted probability from the classifier corresponding to the

m-th omics.

Next, the classifier confidence for each omics is optimized using the cross-entropy loss:

where

is the ground-truth label of the

n-th sample.

Additionally, based on predicted distribution

and the true label

, the confidence score

is computed as follows:

To train the confidence estimator

, the MSE loss is defined as follows:

Finally, the overall gating and confidence loss functions

is given by

2.4.3. Final Objective

The final loss function of MOGOLA integrates all optimization components and is defined as follows:

where

is the cross-entropy loss computed from final output of the Omics-Linked Attention (OLA) mechanism. The hyperparameters

and

are used to balance the contribution of each component.

During training, we first pretrain each omics-specific graph structure using the graph structure loss . Then, the omics-specific graph structure parameters are frozen, and the remaining components—including gating, confidence estimation, and the OLA module—are jointly optimized to minimize . This two-stage training scheme enables the model to first learn robust graph-based representations and then refine inter-omics fusion through confidence-aware learning, ultimately improving prediction accuracy and biological interpretability.

3. Results

To evaluate the performance of the proposed MOGOLA framework, we conducted a comprehensive set of experiments on four publicly available multi-omics datasets.

3.1. Data Sources

We employed four public available multi-omics datasets to evaluate the performance of MOGOLA: BRCA (breast cancer) [

27], KIPAN (kidney cancer) [

28], ROSMAP (Alzheimer’s disease) [

29], and LGG (lower-grade glioma) [

30]. Each dataset contains three omics: mRNA expression (mRNA), DNA methylation (meth), and miRNA expression (miRNA). Specifically, the BRCA dataset is used for PAM50-subtype classification of breast invasive carcinoma, KIPAN for kidney cancer type classification, ROSMAP for Alzheimer’s disease patient versus normal control classification, and LGG for glioma grading.

During the preprocessing stage, we performed systematic feature refinement for each omics following the procedure described in [

17]. Detailed statistics and feature counts are summarized in

Table 1.

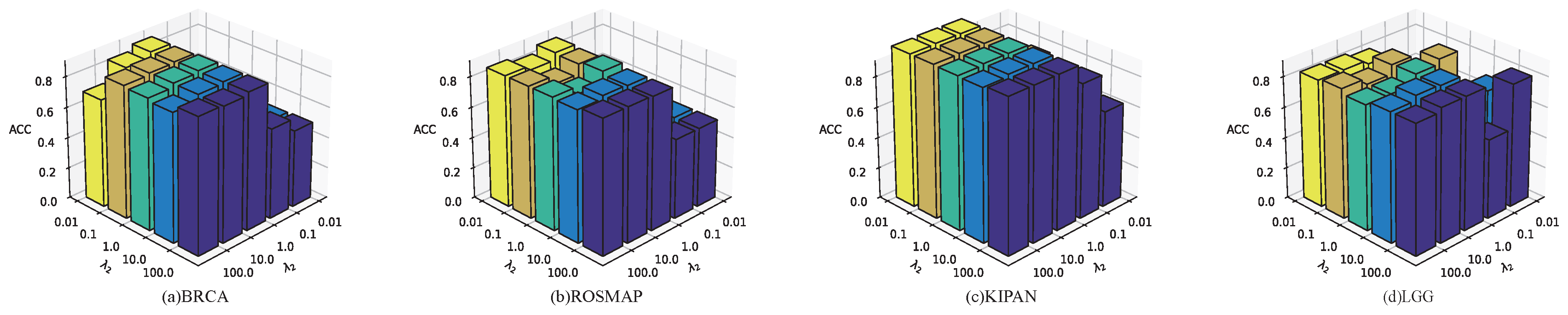

3.2. Loss Function Hyperparameter Experiment

For loss balancing coefficients, the hyperparameters and control the relative contributions of different loss components during training. We perform a grid search strategy to determine suitable values for and , evaluating all combinations selected from {0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100}.

As shown in

Figure 2, the optimal hyperparameter vary across datasets. When both

and

are set to 10, MOGOLA achieves the best performance on the LGG dataset. For all other datasets, MOGOLA gains optimal performance with

=1 and

= 1. These experimental results demonstrate that appropriately weighting each loss component contributes to improved overall algorithm performance.

3.3. Evaluation and Compared with State-of-Art Methods

For multi-class tasks, we used the following evaluation metrics: accuracy rate (ACC), weighted F1 score (F1_weighted), and macro-averaged F1 score (F1_score). For the binary classification task, we employed the accuracy rate (ACC), F1 score (F1), and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for performance evaluation.

For each dataset, 30% of samples were randomly selected as the test set, while the remaining 70% were used for training. The test samples were stratified to preserve the original class distribution. All methods were evaluated using five independent random splits, and the mean ± standard deviation of each metrics was reported to ensure statistical reliability.

Since each dataset exhibits distinct topological characteristics, different hyperparameters were selected accordingly. The hyperparameter k determines the number of nearest neighbors retained for each sample. A smaller k yields a sparser graph and may miss important relationships, while a larger k results in a denser graph that may introduce noise. We tested values of k from 2 to 10 and selected the optimal values for each dataset. The final k values were set to 9, 2, 3, and 7 for the BRCA, ROSMAP, KIPAN, LGG datasets, respectively.

We compared MOGOLA with eleven state-of-the-art classification approaches, including traditional machine learning, deep learning, and multi-omics integration models: Lasso regression (Lasso) [

31], XGBoost [

32], Fully-Connected NN (FCNN) [

33], BSPLSDA [

9], Trusted Multi-View Classification (TMC) [

34], Cascade of Final Multimodal Representations (CF) [

35] Gated Multimodal Unit (GMU) [

36], MOGONET [

17], MMDynamic [

37], CLCLSA [

13] and MOSGAT [

38].

As summarized in

Table 2 and

Table 3, MOGOLA consistently outperforms all baseline methods across both binary and multi-class classification tasks. It achieves the highest accuracy, F1-score, and AUC on all four datasets, demonstrating its superior capability in integrating and interpreting heterogeneous omics data. For the KIPAN dataset, where subtype distinctions are more pronounced, most methods achieve near-perfect performance. Nevertheless, MOGOLA still matched or slightly exceeded the compared methods, highlighting its stability and robustness on multi-classification datasets.

These results indicate that MOGOLA not only maintains strong generalization ability but also provides significant performance gains, particularly on complex multi-classification tasks such as BRCA and LGG.

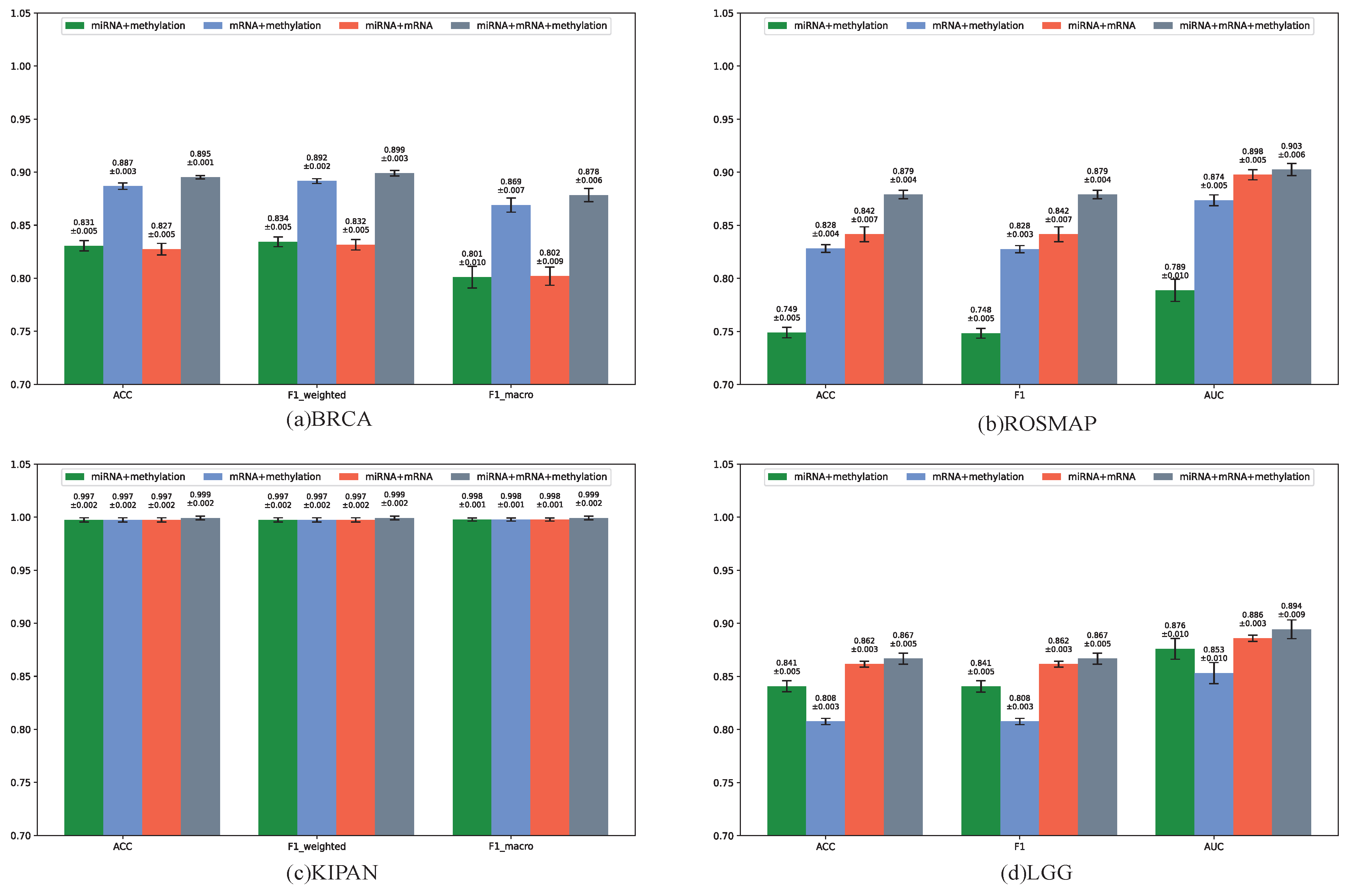

3.4. Model Performance with Different Omics Data Types

To evaluate the necessity of integrating multi-omics data, we performed experiments using different combinations of omics types on the BRCA, ROSMAP, KIPAN, and LGG datasets. Specifically, we compared the performance of MOGOLA when integrating all three omics (miRNA + mRNA + methylation) and when using pairwise combinations (miRNA + mRNA, mRNA + methylation, miRNA + methylation). All experimental settings were consistent with those used in the comparative experiments.

As shown in

Figure 3, integrating all three omics consistently produced the best classification performance, demonstrating the importance of comprehensive multi-omics integration. To further confirm this, we compared three-omics integration with two-omics integration (

Supplementary Material Table S1). Across all datasets, MOGOLA consistently outperformed competing methods in most classification tasks. These findings highlight the effectiveness of graph structure learning for omics data classification and the strong potential of cross-omics learning through the proposed Omics-Linked Attention mechanism in enhancing biomedical data analysis.

3.5. Ablation Analysis

To assess the individual contributions of the MOGOLA’s main components, we conducted a comprehensive ablation study focusing on three key modules: the Graph Structure Learning (GSL) module, the confidence-based Feature Gate module, and the cross-omics Attention (Omics-Linked Attention) module. For ablated models, the GSL module was replaced with a linear layer, the gating mechanism was removed, and the Omics Attention module was bypassed by directly concatenating processed features before classification. Experiments were conducted on all four datasets.

As summarized in

Table 4 and

Supplementary Material Table S2, removing or replacing any module resulted in a noticeable performance decline, confirming the essential role of each component. In particular, replacing the hybrid graph structure with a linear layer led to a substantial accuracy drop, demonstrating that graph structure learning effectively captures sample similarities and enhances multi-omics integration.

To further validate the design of the hybrid graph structure, we tested different combinations of GCN and GAT layers. As shown in

Table 5 and

Supplementary Material Table S3, the GCN-GAT-GCN structure achieved the best performance. This architecture combines GCN’s neighborhood smoothing and GAT’s adaptive neighbor weighting. By alternating GCN and GAT layers, MOGOLA preserves structural information in omics data while enhancing key neighbor aggregation. Compared to pure GCN or GAT architectures, this hierarchical design gains a strong balance between computational efficiency and classification accuracy.

We also evaluated different depths of alternating GCN and GAT layers (

Supplementary Material Table S4). The three-layer architecture achieved the best performance, confirming that it strikes an effective balance between smoothing and expressive feature extraction. Excessively deep or shallow networks degraded performance due to over-smoothing or insufficient pattern learning.

Finally, we assess the effectiveness of MOGOLA’s cross-omics fusion strategy by replacing the graph attention module with alternative fusion mechanisms, including standard self-attention module and a view-correlation discovery network (VCDN) [

17]. As shown in

Table 6 and

Supplementary Materials Table S5, MOGOLA’s graph attention-based fusion consistently outperformed these alternatives. This demonstrates that OLA effectively captures latent functional associations across different omics, whereas VCDN and self-attention offer comparatively limited improvements.

Overall, these results demonstrate that the three primary modules of MOGOLA is critical for capturing multi-omics interactions and achieving robust classification performance, including graph structure learning, confidence-based gating, and cross-omics attention.

4. Biomarker Discovery and Analysis of BRCA

Biomarkers serve as measurable molecular indicators of disease risk, occurrence, and patient prognosis. Accurate identification of biomarkers not only enhances early disease diagnosis and risk assessment but also improves personalized treatment and drug discovery. Moreover, biomarkers discovery is essential for model interpretability and understanding molecular mechanisms [

39].

4.1. Biomarker Discovery of BRCA

In this study, we conducted biomarkers identification analysis on the BRCA dataset. For each sample in the test set, individual features were sequentially masked (set to zero), and the trained MOGOLA model was used to reclassify the modified inputs data. The macro-F1 score was computed as the evaluation metrics. By comparing the performance drops between the complete dataset and each feature-ablated version, we quantified the relative importance of every feature [

40]. MOGOLA has identified 464 mRNA biomarkers, 294 methylation biomarkers, and 136 miRNA biomarkers. Their names and importance scores are provided in the

Supplementary Material Table S6.

Table 7 presents only the top 10 most important biomarkers identified from each omics type.

Several mRNA biomarkers identified in BRCA have been previously implicated in breast cancer progression. C1orf106 [

41] is frequently amplified and overexpressed in basal-like breast cancer. Similarly, SOX11 [

42] is highly expressed in HER2-positive and basal-like subtypes and is strongly associated with recurrence and progression from ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive carcinoma. HPDL [

43], a gene involved in tyrosine metabolism, has been linked to poor prognosis when overexpressed in breast cancer patients.

For DNA methylation-based biomarkers, SOX21 [

44] promotes tumor proliferation, metastasis, and chemoresistance through the PI3K/AKT pathway and the miR-520a-5p/ORMDL3 regulatory axis. Its dysregulation correlates with advanced disease stage, lymph node metastasis, and poor survival. KEGG annotations also reveal several olfactory receptor genes (e.g., OR11H6, OR1J4, OR4N5, OR11G20) [

44]. They are expressed in peripheral tissues and may have broader functions despite their canonical sensory roles. Additionally, ATP10B [

45] is identified as a driver genes associated with high proliferation and recurrence risk in Luminal B-type breast cancer.

Among miRNA biomarkers, hsa-mir-210 [

46] is upregulated under hypoxic conditions through the HIF-1

/VHL pathway and is independently associated with poorer survival outcomes. Hsa-mir-1307 [

47] is significantly overexpressed in tumor tissues compared with adjacent normal tissues and strongly correlated with unfavorable prognosis. Hsa-mir-2355 [

48] promotes immune evasion and chemoresistance in triple-negative breast cancer by interacting with NEAT1 lncRNA to elevate MSLN expression.

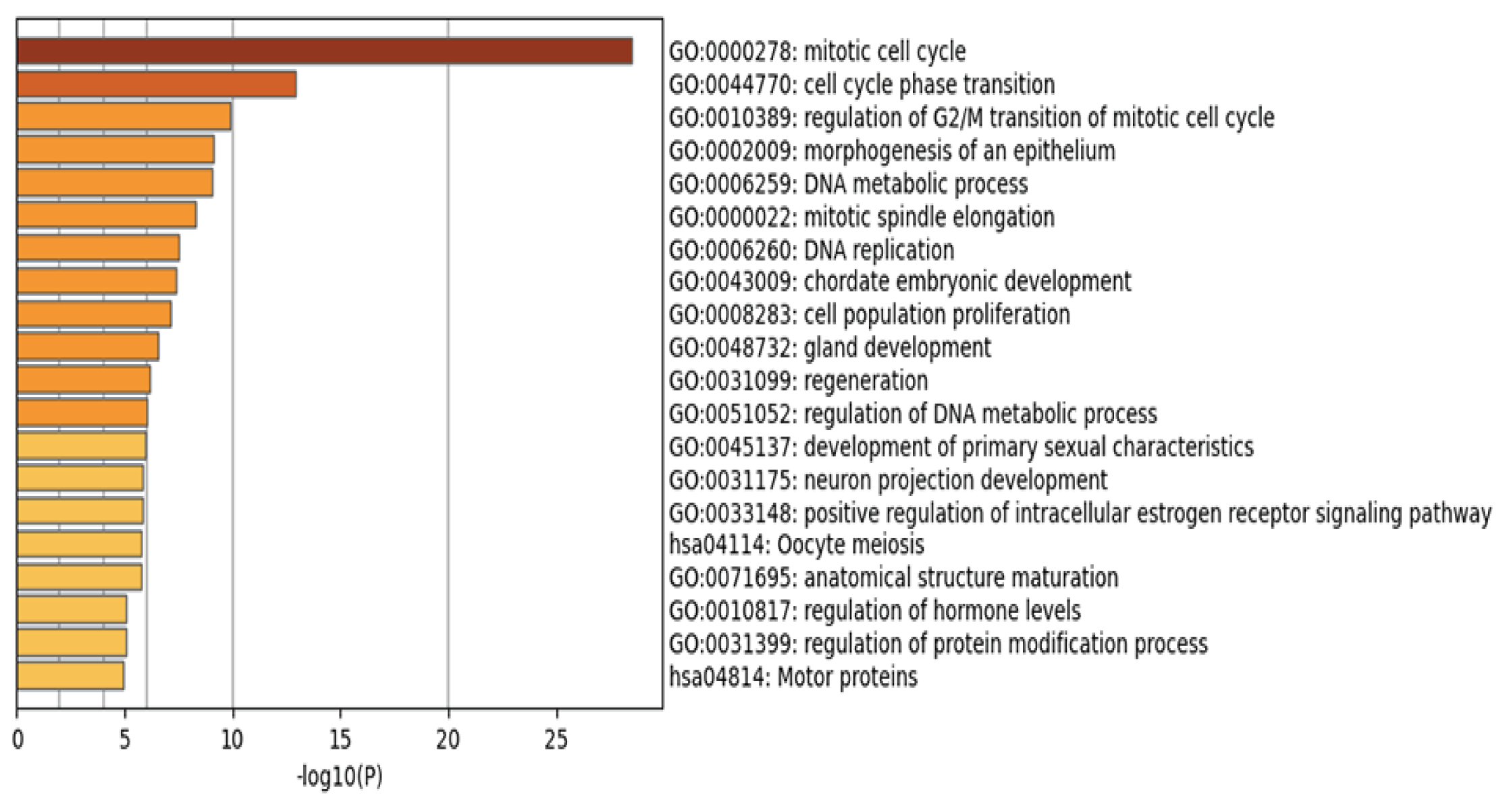

4.2. Pathway and Process Enrichment Analysis

To investigate the biological roles of the identified genes, we conducted pathway and process enrichment analysis using Gene Ontology (GO) Biological Processes and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways through the Metascape platform [

49]. Analyses were performed using all genome-wide genes as the background. Only terms with

p-value < 0.01, minimum count ≥ 3, and enrichment factor > 1.5 were retained.

Terms were clustered based on membership similarity using the Kappa statistic (threshold = 0.3). For each cluster, the most statistically significant term was selected to represent the cluster. p-values were computed using the cumulative hypergeometric distribution, and q-values were generated using the Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

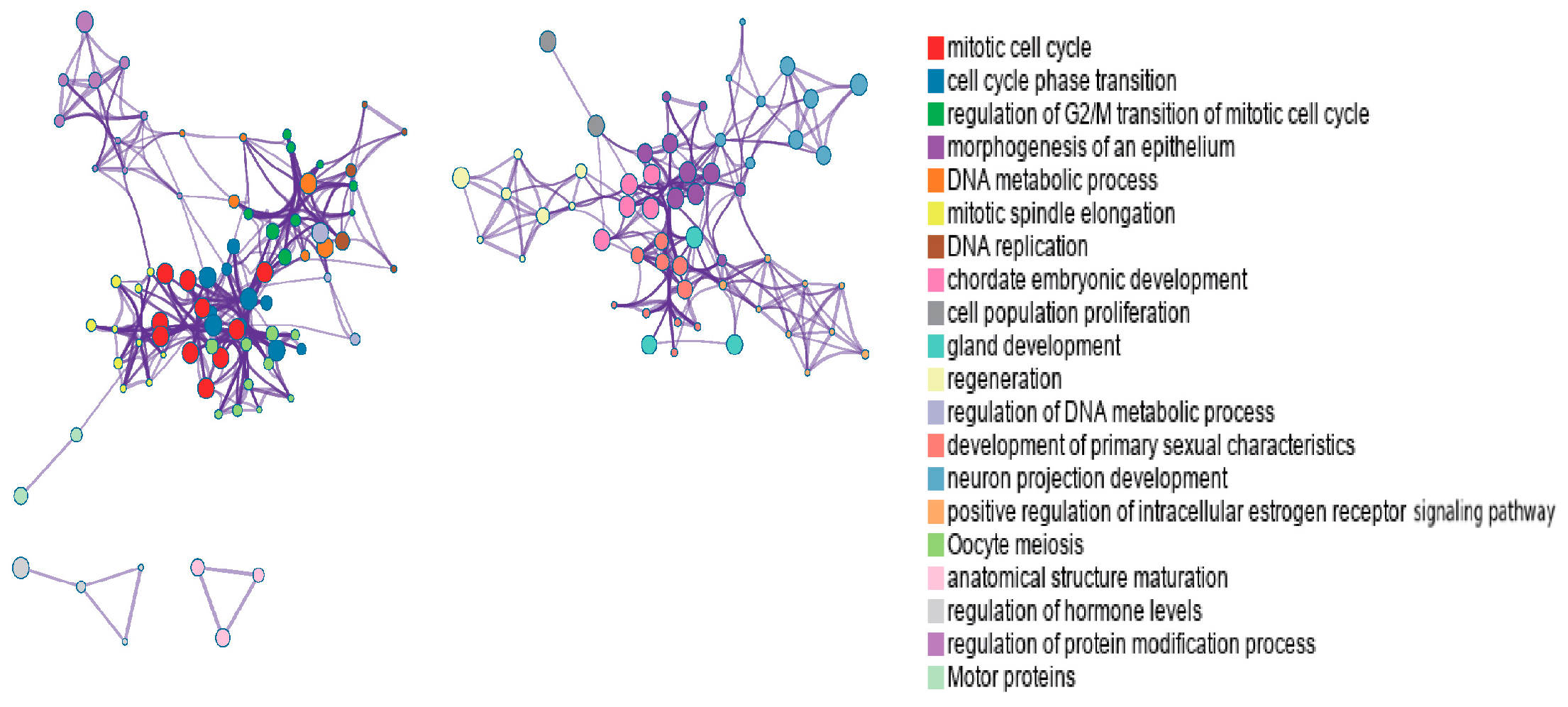

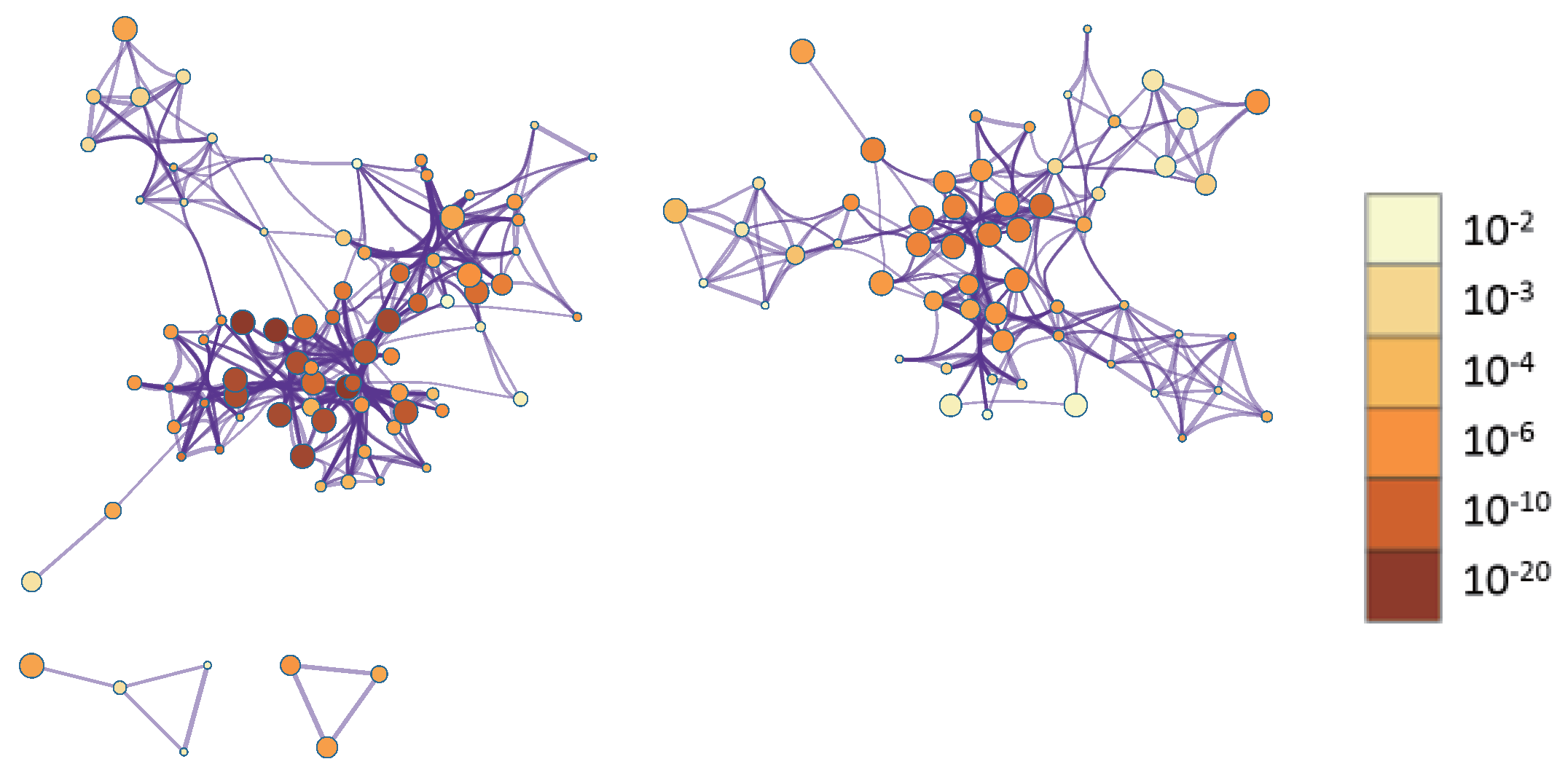

As shown in

Figure 4 and

Supplementary Materials Table S7, the identified genes are involved in multiple biological pathways, consistent with previous studies. For example, breast cancer development is closely associated with dysregulation of the mitotic cell cycle pathway, a key mechanism driving malignant proliferation [

50]. Additionally, abnormal regulation of epithelial morphogenesis contributes to the initiation and progression of breast cancer [

51].

To better visualize relationships between enriched terms, a subset of terms was represented as a network, where edges indicate similarity > 0.3. We selected top-ranked terms from 20 clusters (up to 15 terms per cluster, capped at 250 terms total). Visualization in Cytoscape [

52] colored nodes by cluster ID (

Figure 5) and by

p-value (

Figure 6). In

Figure 5, nodes sharing the same cluster ID are typically positioned close together, while in

Figure 6, terms containing more genes tend to have more significant

p-values.

4.3. Protein–Protein Interaction Analysis and Hub Gene Identification

To identify key mRNAs with potential functional relevance, we constructed a Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) network using STRING [

53] with a high-confidence threshold (0.9). The resulting network (

Supplementary Materials Table S8) was imported into Cytoscape for hub gene analysis using CytoHubba, with detailed results presented in the

Supplementary Materials Table S9. Hub genes were determined based on degree centrality, stress centrality, and betweenness centrality. Nineteen hub genes were identified: HJURP, TROAP, BYSL, CDC20, NOP58, UBE2C, POP1, CBX2, CCT4, CDC6, PLK1, CCNB2, CCNB1, BUB1, BIRC5, CDCA8, KIF2C, TPX2, and AURKB.

Among these, HJURP [

54] is highly expressed in breast cancer and promotes tumor progression by stabilizing the YAP1 protein and activating transcription of NDRG1. BUB1 [

55] and BYSL [

56] are overexpressed in various solid tumors, including breast cancer, and are associated with poor prognosis. AURKB [

57] promotes malignant proliferation of breast cancer cells through its protein stability and is a key driver of breast cancer development. KIF2C [

58] is upregulated in breast cancer and may contribute to disease progression by promoting cell proliferation and migration.

Collectively, these hub genes identified by MOGOLA are well-documented, underscoring their clinical relevance and potential to guide prognostic assessment and therapeutic targeting.

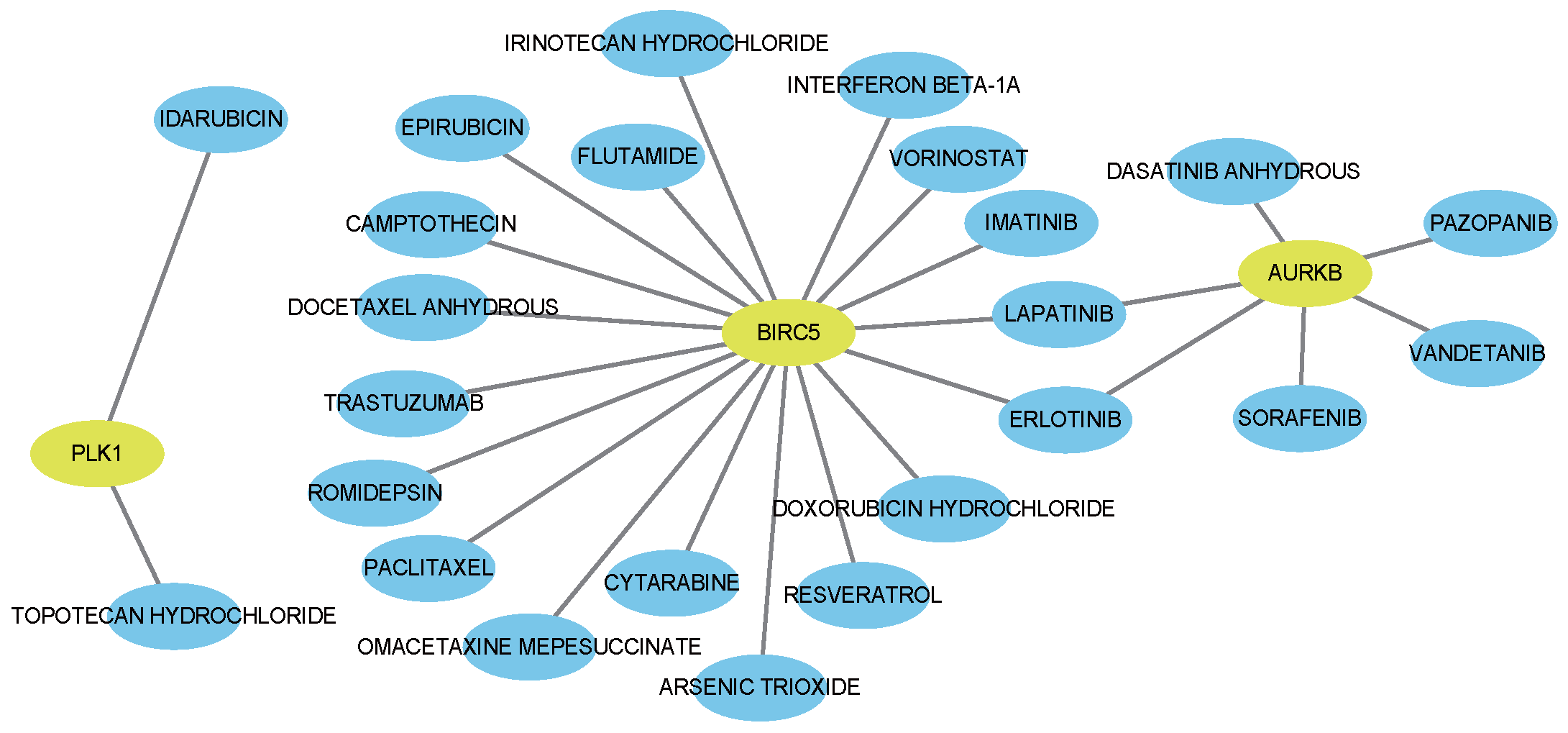

4.4. Drug–Gene Interaction Analysis

Using the Drug–Gene Interaction Database (DGIdb) [

59], we identified FDA-approved agents associated with the hub genes. This analysis yielded 69 drug–gene interactions (

Supplementary Materials Table S10), including 24 antieoplastic agents (visualized in

Figure 7). Notably, eight correspond to drugs already used clinically for breast cancer.

Anthracyclines (e.g., epirubicin, doxorubicin) remain core components of systemic therapy, functioning via DNA intercalation and free-radical generation [

60]. Taxanes (docetaxel, paclitaxel) stabilize microtubules and are central to neoadjuvant, adjuvant, and metastatic treatment [

61]. For patients resistant to anthracyclines or taxanes, irinotecan—particularly in liposomal form—has shown clinical activity, with reported ORRs ranging from 14–23% [

62] and up to 34.5% in heavily pretreated patients [

63].

In HER2-positive disease, trastuzumab greatly improves PFS and OS, while lapatinib demonstrates activity in trastuzumab-resistant cases, especially in combination regimens [

64].

Epigenetic modulators such as vorinostat (SAHA) also show promise. When combined with tamoxifen, vorinostat achieved a clinical benefit rate of 40% in endocrine-resistant ER+ metastatic breast cancer [

65]. When combined with paclitaxel and bevacizumab, it achieved an ORR of 55% with manageable toxicity [

66]. Mechanistically, vorinostat enhances chemosensitivity by destabilizing Hsp90 client proteins [

67] and can suppress proliferation in triple-negative breast cancer [

57].

5. Discussion

High-throughput techniques have produced vast labeled multi-omics datasets, and integrated multi-omics approaches consistently outperform single-omics analyses in disease prediction [

27,

68]. In response to this challenge, we propose MOGOLA, a supervised multi-omics integration method that combines Graph Convolution Networks and Graph Attention Networks for inter-omics representation learning and employs gating and confidence mechanisms to enhance feature selection. This design effectively captures relationships across samples and omics layers. Additionally, we incorporate the Omics-Linked Attention mechanism for fusion across omics types, which reduces computational costs, extracts representative omics-specific features, and uncovers potential cross-omics links.

MOGOLA has been evaluated on cancer subtype datasets and neuropathy grading tasks, achieving superior performance compared with existing models. Additionally, experiments using different omics combinations confirm the importance of integrating multiple omics data types in biomedical applications. Furthermore, visualization of learned embeddings demonstrates clear separation of biological subtypes, reflecting the strong representation capability of MOGOLA. Ablation studies further validate the contributions of the hybrid graph structure, gating and confidence modules, and the Omics-Linked Attention mechanism, with the hybrid graph structure playing a particularly crucial role.

Importantly, MOGOLA identified biologically meaningful biomarkers for each omics type in an end-to-end manner without the need for additional feature selection procedures. In BRCA, the identified biomarkers correspond to clinically relevant pathways, key biological processes, and actionable drug targets, supporting subtype-specific therapeutic strategies such as HER2-targeted treatments.

MOGOLA not only outperforms other models but also provides strong biological interpretability. It highlights dysregulated proliferation, with enrichment in cell cycle and PI3K–Akt signaling as signaling pathways, while PPI analysis identified key hub genes (e.g., CCNA2, CDK1, ESR1). These results align with caner hallmarks and known drug targets, showing that MOGOLA captures disease-driving mechanisms rather than just correlations.

Let m be the number of omics, N the number of samples, and d the number of features. The time complexity of MOGOLA arises from three stages: (1) Graph structure, using two GCN layers and one GAT layer, with complexity of , where H is the maximum hidden dimension. (2) Gating and confidence mechanism, with three linear layers, . (3) Omics fusion and classification, with three linear layers and double normalization, , where h is the number of the head and C the number of classes. Overall, the complexity of MOGOLA is , roughly comparable to MOSGAT and slightly higher than MOGONET.

For parameter complexity analysis, MOGOLA includes a moderate GAT layer, involving fewer parameters than the GAT-heavy MOSGAT design. It has slightly more parameters than the GCN-only MOGONET. The Omics-Linked Attention mechanism introduces less overhead than MOSGAT’s full self-attention module and slightly more than MOGONET’s simple fully connected fusion. Despite this modest increase, MOGOLA delivers substantially better predictive performance.

Although MOGOLA achieves good performance on four test datasets, the algorithm still requires further optimization. The static sample similarity matrix may limit model accuracy, emphasizing the need for dynamic adjustment. In addition, MOGOLA relies on a fixed set from a public dataset, which may introduce substantial non-biological noise when applied to other datasets due to variations in data processing. Such noise can obscure true biological signals and degrade performance, making precise data preprocessing a key future challenge. Moreover, MOGOLA is designed for multi-omics data integration and analysis, and its modular architecture holds promise for extension to single-cell multi-omics data. Exploring these extensions could significantly expand the applicability of our framework to emerging single-cell omics datasets.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we introduced MOGOLA, a supervised multi-omics integration framework designed to analyze increasingly large and complex annotated datasets. By using hybrid graph structure learning, a gating and confidence mechanism, and the Omics-Linked Attention mechanism, MOGOLA effectively extract representative features and reveals potential interaction across diverse omics layers. Extensive experiment evaluations demonstrate the effectiveness and robustness of the method, and biomarker analyses further confirm the biological relevance of the identified features, highlight key network hubs, and reveal actionable therapeutic targets. Moving forward, future work will focus on optimizing the fusion and graph modules and enhancing robustness to data heterogeneity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at

https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biology14121764/s1, Table S1: Performance comparison results for different omics combinations; Table S2: Ablation experimental for KIPAN and LGG; Table S3: Performance of different graph structure configurations for KIPAN and LGG; Table S4: Graph layer depth experiment; Table S5: Cross-Omics fusion mechanism comparison for KIPAN and LGG; Table S6: Biomarkers identified for BRCA; Table S7: Enrichment result; Table S8: Protein–Protein Interaction network; Table S9: Hub genes result; Table S10: Drug-Gene Interactions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.H.; methodology and validation, Z.H. and Y.D.; resources and data curation, J.L. and Z.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.D.; visualization J.L.; writing—review and editing, supervision and funding acquisition, Z.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is financially supported by the Research Foundation of Education Bureau of Guangdong Province, China (No:2025KTSCX054), and the Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou, China (No.2025A03J3712).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions that helped improve the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Network |

| GAT | Graph Attention Network |

| TCPs | True-Class Probabilities |

| OLA | Omics-Linked Attention |

| BRCA | Breast Cancer |

| KIPAN | Kidney Cancer |

| ROSMAP | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| LGG | Lower-Grade Glioma |

References

- Satam, H.; Joshi, K.; Mangrolia, U.; Waghoo, S.; Zaidi, G.; Rawool, S.; Thakare, R.P.; Banday, S.; Mishra, A.K.; Das, G.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing Technology: Current Trends and Advancements. Biology 2023, 12, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, P.H.G.; de Melo, N.C.; Porcari, A.M.; de Carvalho, L.M. Integrating Molecular Perspectives: Strategies for Comprehensive Multi-Omics Integrative Data Analysis and Machine Learning Applications in Transcriptomics, Proteomics, and Metabolomics. Biology 2024, 13, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picard, M.; Scott-Boyer, M.P.; Bodein, A.; Périn, O.; Droit, A. Integration strategies of multi-omics data for machine learning analysis. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 3735–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novoloaca, A.; Broc, C.; Beloeil, L.; Yu, W.H.; Becker, J. Comparative analysis of integrative classification methods for multi-omics data. Briefings Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Y.; Shen, H.T.; Zhu, X. Unsupervised multi-view graph representation learning with dual weight-net. Inf. Fusion 2025, 114, 102669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhanpeng, H.; Jiekang, W. A Multiview Clustering Method With Low-Rank and Sparsity Constraints for Cancer Subtyping. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2022, 19, 3213–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, B.; Song, X.; Lyu, C.; Chen, W.; Xiong, Y.; Wei, D.Q. Subtype-DCC: Decoupled contrastive clustering method for cancer subtype identification based on multi-omics data. Briefings Bioinform. 2023, 24, bbad025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Wiel, M.A.; Lien, T.G.; Verlaat, W.; van Wieringen, W.N.; Wilting, S.M. Better prediction by use of co-data: Adaptive group-regularized ridge regression. Stat. Med. 2016, 35, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Shannon, C.P.; Gautier, B.; Rohart, F.; Vacher, M.; Tebbutt, S.J.; Lê Cao, K.A. DIABLO: An integrative approach for identifying key molecular drivers from multi-omics assays. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 3055–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Yang, F.; Huang, J.; Zhang, C.; Yao, J. Multimodal Dynamics: Dynamical Fusion for Trustworthy Multimodal Classification. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 20675–20685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahlschmidt, S.R.; Ulfenborg, B.; Synnergren, J. Multimodal deep learning for biomedical data fusion: A review. Briefings Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbab569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Dong, C.; Kong, Y.; Zhong, J.F.; Li, M.; Wang, K. Group lasso regularized deep learning for cancer prognosis from multi-omics and clinical features. Genes 2019, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, A.; Zhang, X.; Cao, X.; Ding, Z.; Sha, Q.; Shen, H.; Deng, H.W.; Zhou, W. CLCLSA: Cross-omics linked embedding with contrastive learning and self attention for integration with incomplete multi-omics data. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 170, 108058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corso, G.; Stark, H.; Jegelka, S.; Jaakkola, T.; Barzilay, R. Graph neural networks. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2024, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.C.; You, Z.H.; Huang, D.S.; Kwoh, C.K. Graph representation learning in bioinformatics: Trends, methods and applications. Briefings Bioinform. 2021, 23, bbab340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valous, N.A.; Popp, F.; Zörnig, I.; Jäger, D.; Charoentong, P. Graph machine learning for integrated multi-omics analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 131, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Shao, W.; Huang, Z.; Tang, H.; Zhang, J.; Ding, Z.; Huang, K. MOGONET integrates multi-omics data using graph convolutional networks allowing patient classification and biomarker identification. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar]

- Petar, V.; Guillem, C.; Arantxa, C.; Adriana, R.; Pietro, L.; Yoshua, B. Graph Attention Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, W.; Shen, Y.; Feng, S.; Wang, T.; Shang, X.; Peng, J. Integrative graph-based framework for predicting circRNA drug resistance using disease contextualization and deep learning. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 6619–6630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; He, C.; Wei, P.; Su, Y.; Xia, J.; Zheng, C. Prediction of circRNA-disease associations based on the combination of multi-head graph attention network and graph convolutional network. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.U.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Guyon, I., Luxburg, U.V., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lei, Y.; Peng, L.; Shi, X.; Yuan, C.; Zhu, X. Multiplex Graph Representation Learning Via Dual Correlation Reduction. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 12814–12827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Introduction to machine learning: K-nearest neighbors. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbière, C.; THOME, N.; Bar-Hen, A.; Cord, M.; Pérez, P. Addressing Failure Prediction by Learning Model Confidence. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Wallach, H., Larochelle, H., Beygelzimer, A., d’Alché-Buc, F., Fox, E., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.H.; Liu, Z.N.; Mu, T.J.; Hu, S.M. Beyond Self-Attention: External Attention Using Two Linear Layers for Visual Tasks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 5436–5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2012, 490, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, J.N.; Collisson, E.A.; Mills, G.B.; Shaw, K.R.M.; Ozenberger, B.A.; Ellrott, K.; Shmulevich, I.; Sander, C.; Stuart, J.M. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.A.; Schneider, J.A.; Buchman, A.S.; Barnes, L.L.; Boyle, P.A.; Wilson, R.S. Overview and findings from the rush Memory and Aging Project. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2012, 9, 646–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Xiao, Y.; Ren, J.; Zuo, C.; Mu, L.; Li, Q.; Song, Y. Ferroptosis and low-grade Glioma: The breakthrough potential of NUAK2. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 234, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranstam, J.; Cook, J.A. LASSO regression. Br. J. Surg. 2018, 105, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD’16), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schwenker, F.; Trentin, E. Pattern classification and clustering: A review of partially supervised learning approaches. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2014, 37, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zhang, C.; Fu, H.; Zhou, J.T. Trusted Multi-View Classification with Dynamic Evidential Fusion. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 2551–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Gao, L.; Yokoya, N.; Yao, J.; Chanussot, J.; Du, Q.; Zhang, B. More Diverse Means Better: Multimodal Deep Learning Meets Remote-Sensing Imagery Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 4340–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arevalo, J.; Solorio, T.; Montes-y Gomez, M.; Gonzalez, F.A. Gated multimodal networks. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 10209–10228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Tang, C.; Wan, Z.; Hu, C.; Zhang, W. Multi-Level Confidence Learning for Trustworthy Multimodal Classification. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2023, 37, 11381–11389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, W.; Zhao, Y.; Pang, S. MOSGAT: Uniting Specificity-Aware GATs and Cross Modal-Attention to Integrate Multi-Omics Data for Disease Diagnosis. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 5624–5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Tashi, Q.; Saad, M.B.; Muneer, A.; Qureshi, R.; Mirjalili, S.; Sheshadri, A.; Le, X.; Vokes, N.I.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J. Machine Learning Models for the Identification of Prognostic and Predictive Cancer Biomarkers: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Park, C.Y.; Theesfeld, C.L.; Wong, A.K.; Yuan, Y.; Scheckel, C.; Fak, J.J.; Funk, J.; Yao, K.; Tajima, Y.; et al. Whole-genome deep-learning analysis identifies contribution of noncoding mutations to autism risk. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Liu, C.; Yang, D.; Song, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, M.; Xu, W.; Li, X.; Ding, S.; et al. C1orf106, an innate immunity activator, is amplified in breast cancer and is required for basal-like/luminal progenitor fate decision. Sci.-China-Life Sci. 2019, 62, 1229–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Nabavi, S. A multimodal graph neural network framework for cancer molecular subtype classification. BMC Bioinform. 2024, 25, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazemi, M.; Yanes, B.; Martinez, M.L.; Walker, H.J.; Pham, K.; Collins, M.O.; Bard, F.; Rainero, E. The extracellular matrix supports breast cancer cell growth under amino acid starvation by promoting tyrosine catabolism. PLoS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Tang, Z.; Lai, C.C. The roles and mechanism of olfactory receptors in non-olfactory tissues and cells. Prog. Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 47, 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ramshankar, V.; Lochan G, A.; Radhakrishnan, V.; Krishnamurthy, A.; Mukherhee, T.A.; Arya, D.; Gowda, C.; Bahl, A.; Gore, A.; Bipte, S. 19P Molecular subtyping and prediction of risk of recurrence for early stage receptor positive breast cancer for using Nanostring nCounter: First study from India. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, S1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps, C.; Buffa, F.M.; Colella, S.; Moore, J.; Sotiriou, C.; Sheldon, H.; Harris, A.L.; Gleadle, J.M.; Ragoussis, J. hsa-miR-210 Is Induced by Hypoxia and Is an Independent Prognostic Factor in Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumer, O.E.; Schelzig, K.; Jung, J.; Li, X.; Moros, J.; Schwarzmüller, L.; Sen, E.; Karolus, S.; Wrner, A.; Rodrigues de Melo Costa, V.; et al. Selective arm-usage of pre-miR-1307 dysregulates angiogenesis and affects breast cancer aggressiveness. BMC Biol. 2025, 23, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, N.H.; Eissa, R.A.; de Bruyn, M.; El Tayebi, H. NEAT1: Culprit lncRNA linking PIG-C, MSLN, and CD80 in triple-negative breast cancer. Life Sci. 2022, 299, 120523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, B.; Pache, L.; Chang, M.; Khodabakhshi, A.H.; Tanaseichuk, O.; Benner, C.; Chanda, S.K. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neill, N.J.; Satpathy, S.; Krug, K.; Meena, J.K.; Ramesh Babu, N.; Calderon, C.; Reed, D.; Weber, M.J.; Dobrolecki, L.E.; Lewis, A.; et al. Integrative Proteogenomics and Forward Genetics Reveal a Novel Mitotic Vulnerability in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2025, 15, 2326–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingthorsson, S.; Traustadottir, G.A.; Gudjonsson, T. Cellular plasticity and heterotypic interactions during breast morphogenesis and cancer initiation. Cancers 2022, 14, 5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein–protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Jia, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, C.; Ju, S.; et al. HJURP regulates cell proliferation and chemo-resistance via YAP1/NDRG1 transcriptional axis in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriramulu, S.; Thoidingjam, S.; Siddiqui, F.; Brown, S.L.; Movsas, B.; Walker, E.; Nyati, S. BUB1 Inhibition Sensitizes TNBC Cell Lines to Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, Y.; Yang, S.; Sheng, J.; Yin, Y.; Fan, J.; Zhou, J. Bystin-like protein is upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma and required for nucleologenesis in cancer cell proliferation. Cell Res. 2009, 19, 1150–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Y.; Zhang, N.; Li, F.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y.; Li, F.; Cui, X.; Zhao, Q.; Cai, Y.; Jin, J. Histone Acetyltransferase MOF-Mediated AURKB K215 Acetylation Drives Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation via c-MYC Stabilization. Cells 2025, 14, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Cai, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ma, J.; Zhao, K. miR-4484 suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma progression via targeting KIF2C. RNA Biol. 2025, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, M.; Stevenson, J.; Stahl, K.; Basu, R.; Coffman, A.; Kiwala, S.; McMichael, J.F.; Kuzma, K.; Morrissey, D.; Cotto, K.; et al. DGIdb 5.0: Rebuilding the drug–gene interaction database for precision medicine and drug discovery platforms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1227–D1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.; Wang, W.; Luo, X.; Wang, Y. Cluster analysis of hotspots and research trends of epirubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: A bibliometric study. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1616162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahdat, L.T. Novel Combinations for the Treatment of Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cancers 2010, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, E.A.; Hillman, D.W.; Mailliard, J.A.; Ingle, J.N.; Ryan, J.M.; Fitch, T.R.; Rowland, K.M.; Kardinal, C.G.; Krook, J.E.; Kugler, J.W.; et al. Randomized Phase II Study of Two Irinotecan Schedules for Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer Refractory to an Anthracycline, a Taxane, or Both. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 2849–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdev, J.; Munster, P.; Northfelt, D.; Han, H.; Ma, C.; Maxwell, F.; Wang, T.; Belanger, B.; Zhang, B.; Moore, Y.; et al. Phase I study of liposomal irinotecan in patients with metastatic breast cancer: Findings from the expansion phase. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 185, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slamon, D.J.; Leyland-Jones, B.; Shak, S.; Fuchs, H.; Paton, V.; Bajamonde, A.; Fleming, T.; Eiermann, W.; Wolter, J.; Pegram, M.; et al. Use of Chemotherapy plus a Monoclonal Antibody against HER2 for Metastatic Breast Cancer That Overexpresses HER2. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munster, P.N.; Thurn, K.T.; Thomas, S.; Raha, P.; Lacevic, M.; Miller, A.J.; Melisko, M.E.; Ismail-Khan, R.; Rugo, H.S.; Moasser, M.M.; et al. A phase II study of the histone deacetylase inhibitor vorinostat combined with tamoxifen for the treatment of patients with hormone therapy-resistant breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 1828–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, B.; Fiskus, W.; Cohen, B.; Pellegrino, C.; Hershman, D.; Chuang, E.; Luu, T.; Somlo, G.; Goetz, M.; Swaby, R.; et al. Phase I-II study of vorinostat plus paclitaxel and bevacizumab in metastatic breast cancer: Evidence for vorinostat-induced tubulin acetylation and Hsp90 inhibition in vivo. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 132, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Hershman, D.; Bhalla, K.; Fiskus, W.; Pellegrino, C.; Andreopoulou, E.; Makower, D.; Kalinsky, K.; Fehn, K.; Fineberg, S.; et al. A phase I-II study of the histone deacetylase inhibitor vorinostat plus sequential weekly paclitaxel and doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide in locally advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, 146, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ding, Z.; Tao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Y. Generative Multi-View Human Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 6211–6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).