1. Introduction

UV-B radiation (280–315 nm) is a ubiquitous environmental factor influencing the evolution and ecology of organisms worldwide, with levels rising in tandem with solar altitude angle [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The higher the altitude, the larger the solar altitude angle, and consequently, the greater the UV-B radiation. The thin atmospheres and historical ozone depletion of high-altitude regions result in persistently elevated UV-B levels, which can be up to 2–3 times higher than those found in lowlands [

5,

6].

The high energy of UV-B radiation causes severe biological damage, including DNA mutations, protein denaturation, and oxidative stress. For aquatic ecosystems, UV-B can penetrate clear water bodies unimpeded, threatening the survival and reproduction of various species [

7]. In response, high-altitude organisms have evolved diverse defense mechanisms: for instance,

Euglena in Dianchi Lake synthesize excessive mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) [

8]; green algae effectively repair UV-induced DNA damage through photo repair enzymes to maintain genomic stability [

9]; Qinghai–Tibet Plateau loaches possess thicker and denser scales, with the development of external protective structures reducing UV-B penetration into deep tissues [

10]; plateau cladocerans precisely avoid UV-B radiation through behavioral patterns of ascending only at dawn and dusk [

11]. These defense mechanisms involve morphological changes, behavioral modifications, and multi-level physiological adaptations, shaping survival and ecological interactions through alterations in growth, reproductive success, and overall fitness, thereby influencing ecosystem dynamics [

12]. The defense strategies of these organisms provide a reference direction for analyzing the UV-B resistance mechanism of

Artemia.

Artemia, known as brine shrimp, can be found at altitudes ranging from −154 m to 5040 m [

13]. These extremophiles are able to thrive in hypersaline lakes around the world, showing resilience to various stressors, such as intense UV-B radiation, temperature fluctuations, and osmotic stress [

14]. Broad environmental adaptability renders them a valuable model for investigating stress tolerance [

15]. Critically,

Artemia exhibit two distinct reproductive modes—bisexual reproduction and obligate parthenogenesis—offering a unique avenue to dissect how reproductive modes interact with environmental stress tolerance [

16]. Research has shown that bisexual individuals outperform parthenogenetic lineages under temperature stress [

17,

18]; it is unclear if this extends to UV-B resistance. A systematic investigation of

Artemia’s UV-B resistance at various altitudes is lacking. The influence of reproductive modes on

Artemia’s UV-B resistance and their interaction with altitude is not well understood. Previous studies have indicated stage-specific sensitivity, with nauplii being more vulnerable than adults [

19], but these studies were limited to specific stages and did not account for different altitudinal species/lineages or reproductive modes.

This highlights the need to address the following critical questions: (1) How does UV-B tolerance vary among Artemia species/lineages across altitudinal gradients? (2) Do reproductive modes (bisexual vs. parthenogenetic) influence UV-B resistance? If this is the case, how do they interact with altitude? (3) Are there specific patterns of tolerance at different developmental stages (embryos, nauplii, adults)?

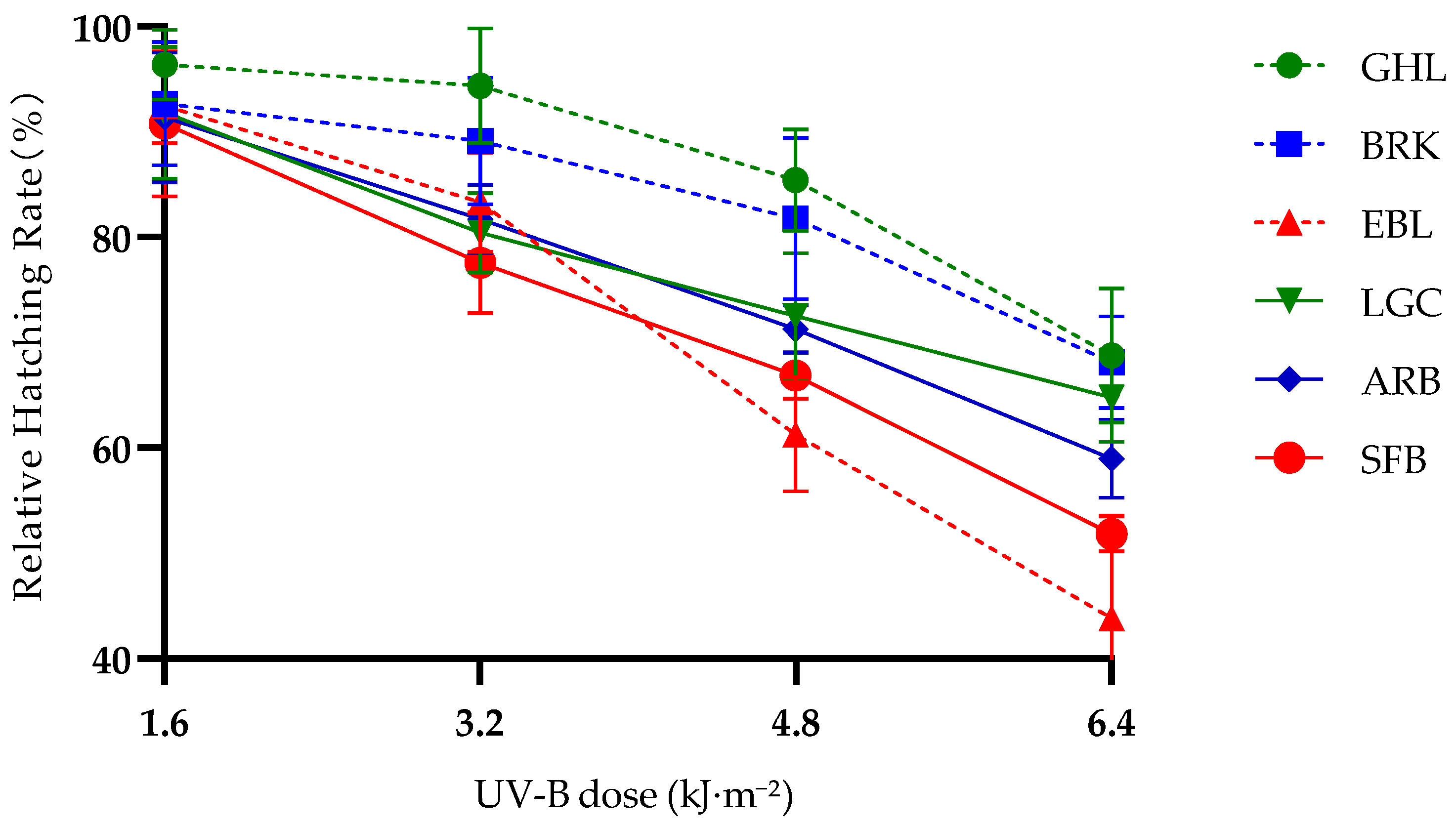

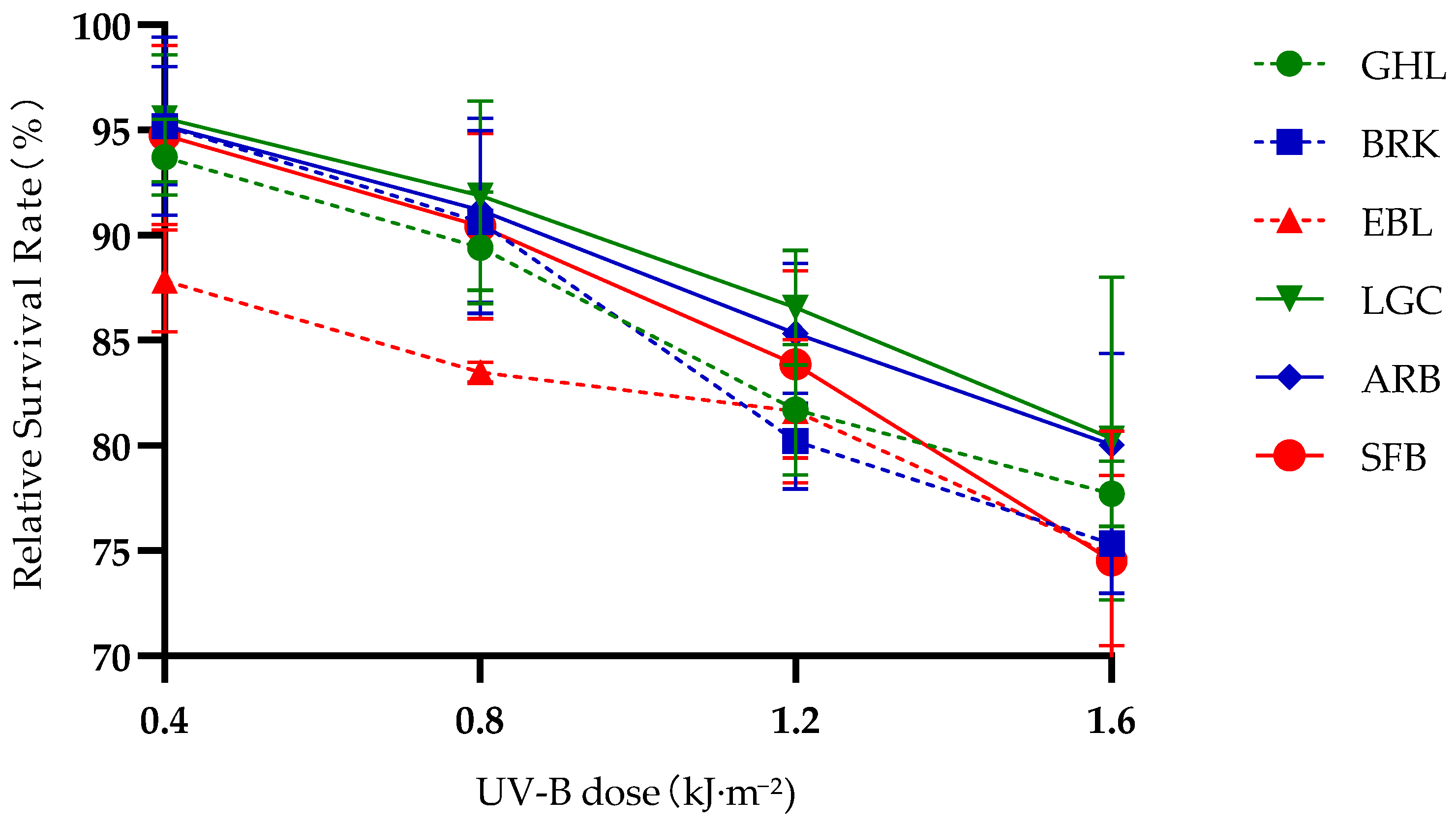

Studying the differences in ultraviolet tolerance among six Artemia species/lineages with different altitudes and reproductive modes is the first step to gain an in-depth understanding of the mechanisms involved. Comparing UV-B tolerance across six Artemia species/lineage with differing altitudes and reproductive modes, we assessed hatching success for embryos without a protective chorion, as well as relative survival rates for nauplii and adults under varying UV-B levels. It is the first time to systematically integrate three core dimensions—altitudinal gradients, reproductive modes, and developmental stages—to reveal the adaptive patterns of UV-B resistance in Artemia, thereby providing a new perspective for the study of biological adaptation mechanisms in extreme environments.

4. Discussion

The present study systematically investigated the effects of UV-B, altitudinal gradients, and reproductive modes on the hatching and survival performance of six Artemia species/lineages across three developmental stages. By integrating these three core dimensions for the first time, we revealed three distinct adaptive patterns of Artemia in response to UV-B stress, which not only enriches our understanding of the stress adaptation mechanisms of extremophiles but also provides empirical support for the synergistic regulation of environmental and biological traits in shaping species tolerance.

Our results confirmed that high-altitude

Artemia species/lineages exhibit significantly superior UV-B tolerance compared to low-altitude counterparts, reflected in higher relative hatching rates of embryos and longer survival periods of adults under high-dose UV-B stress. Notably, this altitude-associated tolerance shows distinct developmental stage specificity: the differences between high-altitude and low-altitude strains of

Artemia mainly manifest under prolonged or stronger UV-B irradiation. Studies have shown that low doses of UV-B can exert positive effects on organisms, promoting the expression of relevant genes and the production of more proteases [

29]. However, at high doses, UV-B damages cellular structures and molecular mechanisms [

30]. Organisms in high-altitude areas develop greater resistance when exposed to high doses of UV-B. For instance, benthic macroinvertebrates in high-altitude areas develop greater pigmentation to mitigate the impacts of UV-B [

31]. Compared with organisms inhabiting low-altitude regions, those in high-altitude areas synthesize a greater abundance of UV-B resistance-related metabolites to safeguard cellular structures [

32]. This “high-altitude–high tolerance” pattern is not limited to UV-B resistance; high-altitude

Artemia species/lineages also show enhanced adaptability to other concurrent extreme environmental factors, such as low temperatures and high salinity in plateau habitats [

33]. This “high-altitude–high-tolerance” correlation is not unique to

Artemia; it is equally prevalent in other biological taxa. For example, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and plants at high altitudes show higher resistance than their counterparts at low altitudes [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. Such comprehensive stress tolerance may stem from long-term directional selection in high-altitude environments, which may drive the evolution of intrinsic protective traits—for example, the formation of thicker cyst shells, or the enhancement of DNA repair enzyme activity and antioxidant capacity [

39,

40].

Reproductive mode plays a key regulatory role in

Artemia’s UV-B tolerance, but this effect varies significantly across developmental stages, presenting a distinct stage-specific pattern. At the embryonic stage, parthenogenetic lineages showed higher relative hatching rates than bisexual species at the same altitude and UV-B dose, contradicting their lower tolerance at the naupliar and adult stages. This unique phenomenon may be related to the maternal environment: parthenogenetic

Artemia in the wild may ingest more food sources rich in MAAs and transfer these compounds to their embryos through reproductive organs, thereby enhancing embryonic resistance to UV-B damage [

41,

42,

43]. In contrast, the naupliar and adult experiments were conducted under standardized laboratory feeding conditions, eliminating dietary interference and thus reflecting the intrinsic differences between reproductive modes. Because parthenogenetic females may transfer MAAs or other protective compounds to embryos, some of the observed UV-B tolerance may reflect maternal effects rather than intrinsic genetic differences. In the future, raising synchronized generations under uniform laboratory conditions will help separate maternal influence from genetic factors.

At the naupliar stage, bisexual species maintained higher relative survival rates than parthenogenetic lineages across all altitude ranges. At the adult stage, bisexual species showed more stable survival under prolonged UV-B exposure (96–120 h), with significant positive correlations between reproductive mode and survival rate (r = 0.533 *–0.74 **). The phenomenon that bisexual reproduction confers higher UV-B resistance than parthenogenesis also exists in other taxa. For example, bisexual

Eucypris virens exhibit higher UV-B resistance than parthenogenetic individuals [

44]. In addition to UV-B resistance, bisexual species also show better tolerance to climatic stress, cold stress, and a variety of other environmental stresses. This phenomenon has been reported in European blueberry psyllid, aphids, and plants [

45,

46,

47]. Under the same altitude conditions and UV-B stress, the correlation of “bisexual reproduction–high resistance” is remarkably evident in

Artemia at both the adult and naupliar stages. SFB has become an invasive species in the Mediterranean region, and, compared with the native parthenogenetic

Artemia lineages in the Mediterranean Sea, it has a wider tolerance range to extreme environments. Toxicity tests conducted on it show that the enzymes in SFB exhibit stage-specific resistance and possess a gene-regulated stress-resistant molecular chaperone system [

48]. Studies have shown that the bisexual

Artemia from Lake Urmia inherently exhibit stronger tolerance to UV-B and salinity, and this adaptability may also be associated with their inherent stress-resistant genes [

49]. However, taxa that exhibit both bisexual and parthenogenetic reproductive modes are relatively scarce. This necessitates additional data to validate the observed patterns, refine the existing framework, and enhance the robustness of this conclusion [

50].

In addition to the above two adaptive patterns,

Artemia possesses a third adaptive pattern. Our study clearly demonstrated that

Artemia’s UV-B tolerance varies significantly with developmental stages, following the pattern of “adults > nauplii”. Adults showed the strongest resistance: they could maintain stable survival under moderate UV-B doses (0.8–2.4 kJ·m

−2) in the short term (24–48 h) and tolerate higher doses for longer periods. This advantage is likely due to their mature physiological systems, sufficient energy reserves, and complex cuticle composed of chitin, proteins, and minerals—all of which provide structural protection and support efficient damage repair [

51,

52]. The high tolerance of adult

Artemia to UV-B may also be associated with other protective mechanisms, such as pigment deposition, regulation via endogenous enzymatic/non-enzymatic systems, or light-avoidance behavior. Notably, similar protective mechanisms have been documented in both Antarctic hair grass and bdelloid rotifers [

53,

54]. Although these indicators were not directly measured in this study, these findings still provide a direction for subsequent exploration of the specificity of protective mechanisms in adult individuals. Even under low UV-B doses, the relative survival rate of nauplii decreases significantly. This may be because nauplii exhibit immature physiological functions and limited energy reserves, which hinder their ability to cope with the dual challenges of UV-B-induced energy consumption and the metabolic demands of damage repair [

55]. This “adult developmental stage–high resistance” association is also not exclusive to

Artemia. Fish are a typical representative of aquatic animals. Adult fish can develop a thicker epidermal layer and scales to resist UV-B radiation [

56].

5. Conclusions

By analyzing the UV-B tolerance of six Artemia species/lineages across different altitudes (113–4700 m), reproductive modes (bisexual reproduction and parthenogenesis), and developmental stages (embryos, nauplii, and adults), this study revealed the core adaptive characteristics of Artemia in response to UV-B stress. Artemia at high altitudes have developed an “altitude adaptive barrier” through long-term selection under extreme UV-B radiation, exhibiting significantly higher UV-B resistance than low-altitude populations. Particularly under high-dose UV-B exposure, the declines in their embryo relative hatching rates and adult survival rates are much smaller. At the same altitude, adult Artemia with bisexual reproduction show far greater resistance to long-term high-intensity UV-B than parthenogenetic lineages. However, parthenogenetic Artemia have a higher embryo relative hatching rate, presenting developmental stage-specific differences. Additionally, the UV-B resistance of adult Artemia is significantly higher than that of nauplii: low-dose UV-B can already affect nauplii survival, while adults can tolerate medium-dose UV-B. Among these findings, high-altitude bisexual Artemia are preferred materials for UV-B-resistant breeding. Meanwhile, this study clarifies the synergistic regulatory mechanism between altitude and biological traits in shaping Artemia’s UV-B tolerance, providing theoretical support for research on biological adaptation to extreme environments and stress-resistant breeding practices.