Effect of Proximity to Failure in Resistance Training on Circulating Levels of Neuroprotective Biomarkers

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Participants and Sample Size Justification

2.3. Training Protocol

2.4. Training Load Instructions and Adjustments

2.5. Anthropometric Assessments

2.6. Back Squat and Bench Press Technique

2.7. One-Repetition Maximum (1 RM) Testing

2.8. Blood Sampling and Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Acute and Chronic Biomarker Responses

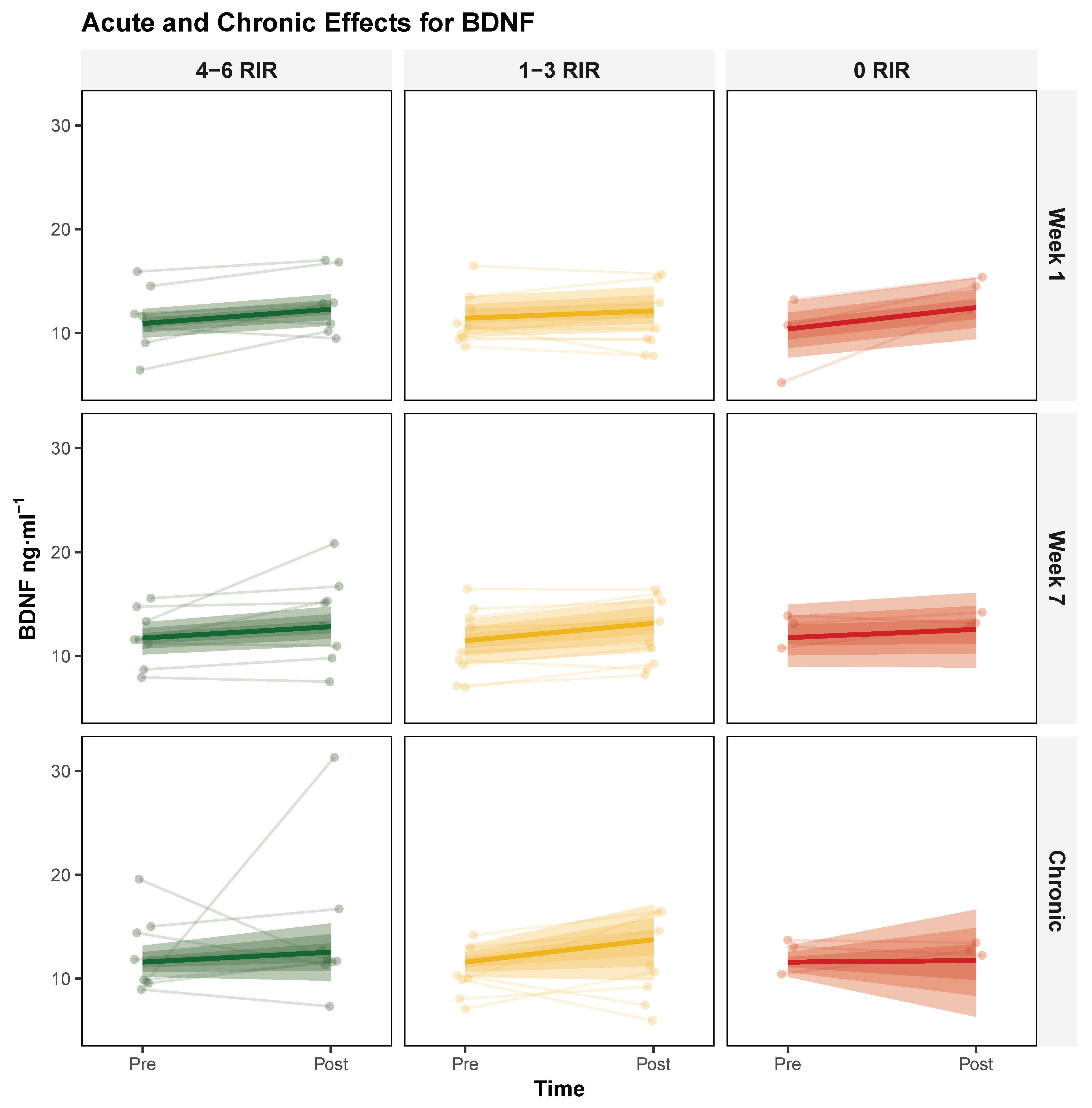

3.1.1. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF)

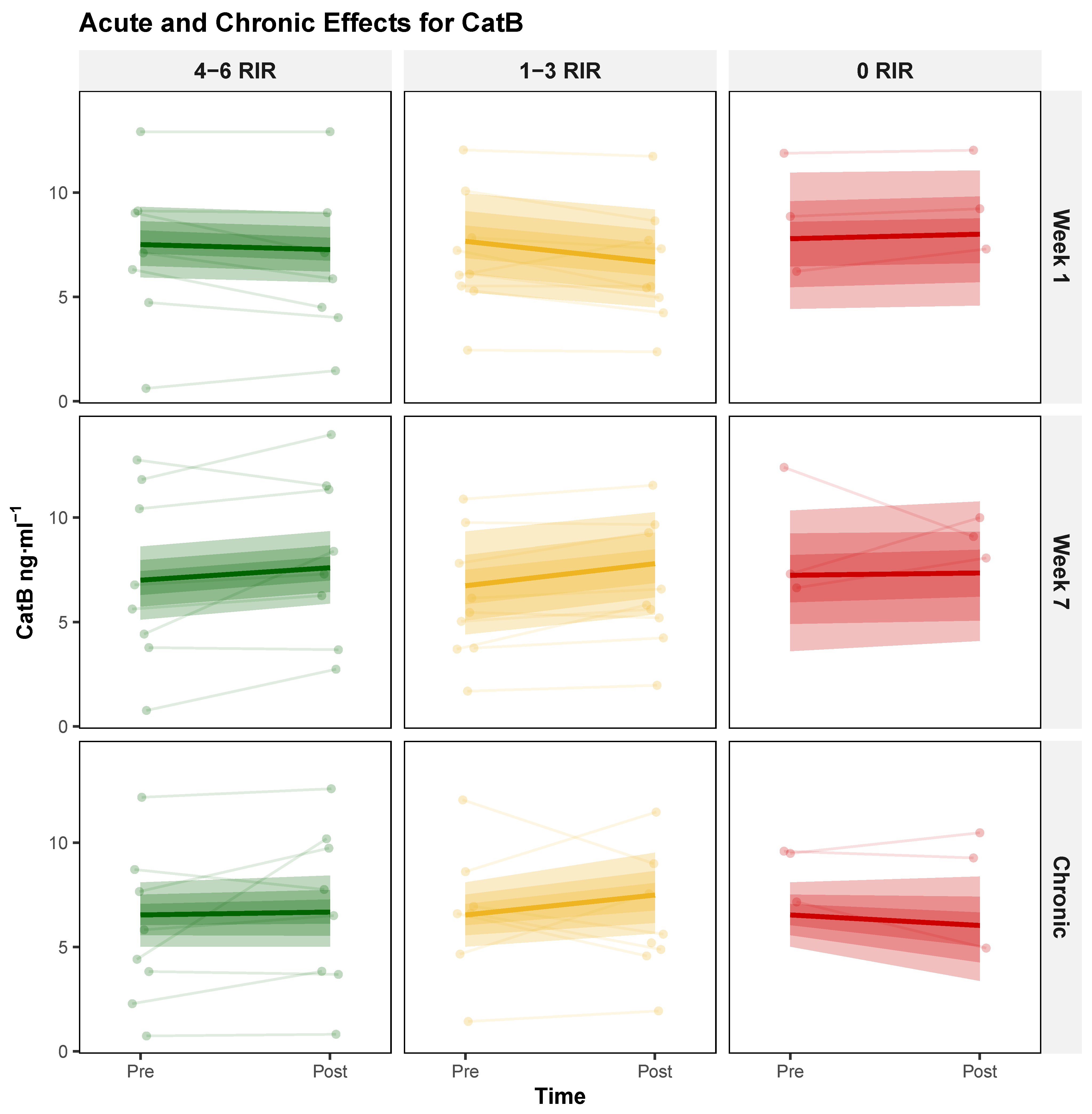

3.1.2. Cathepsin B (CatB)

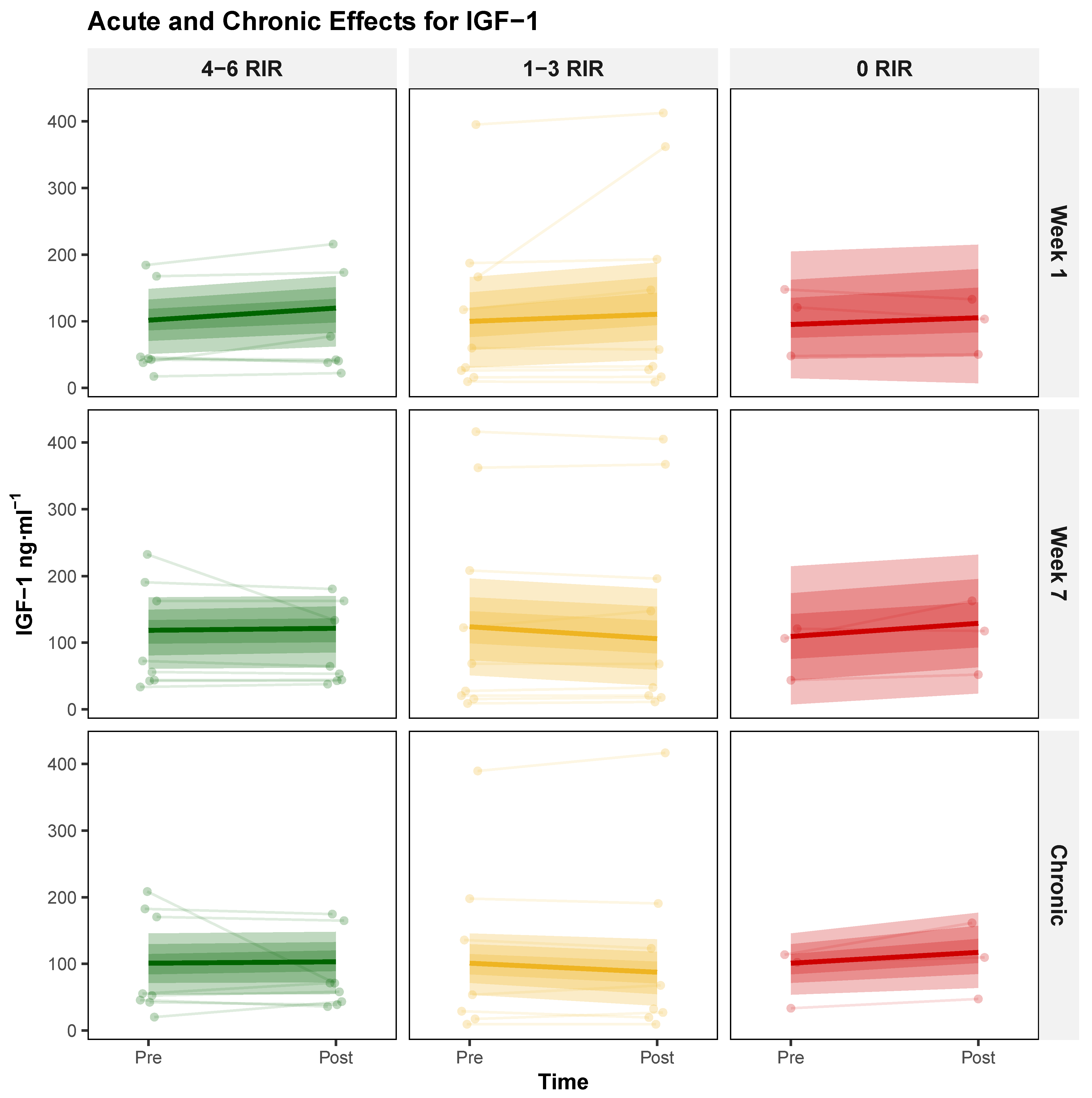

3.1.3. Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1)

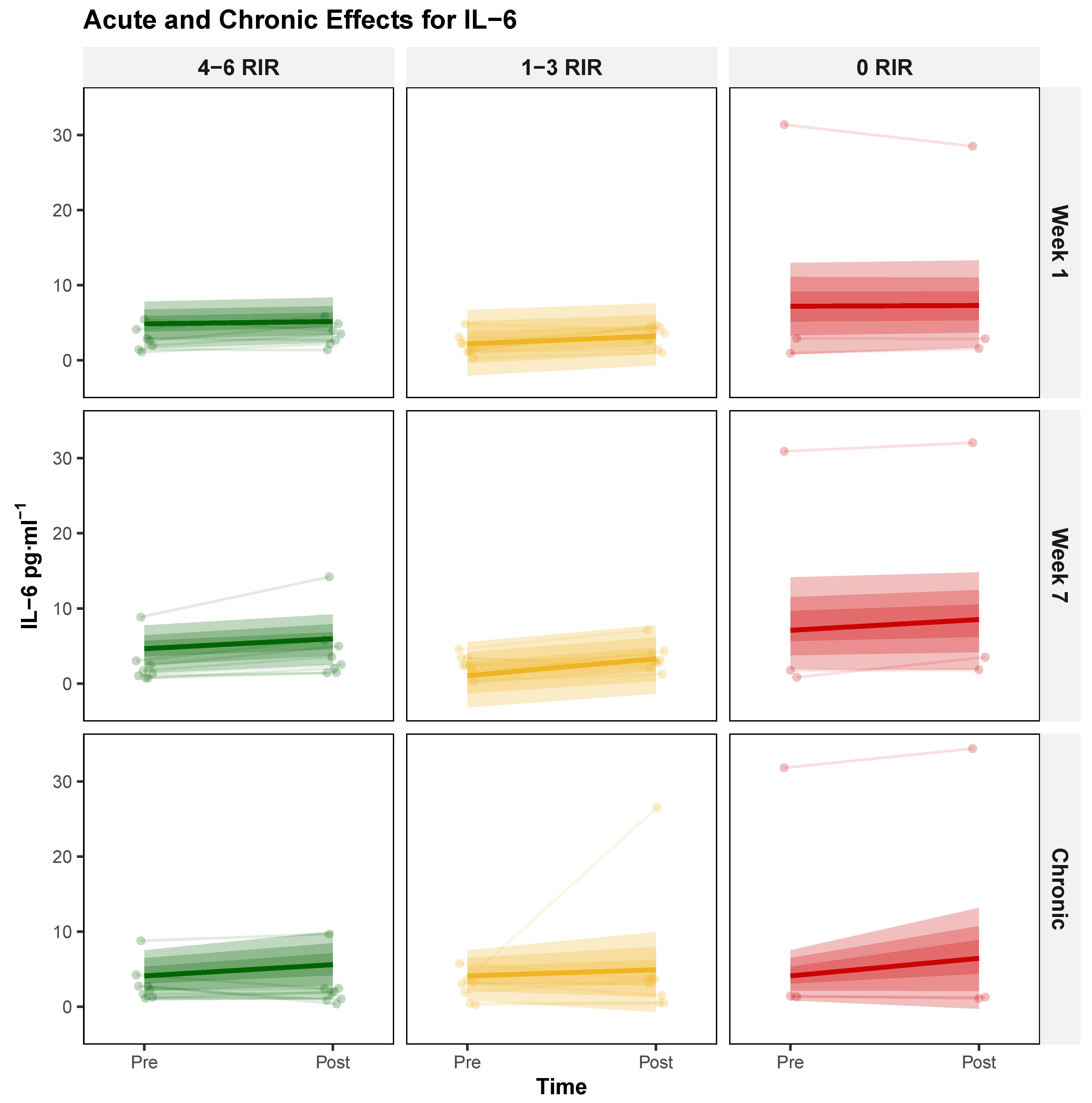

3.1.4. Interleukin 6 (IL-6)

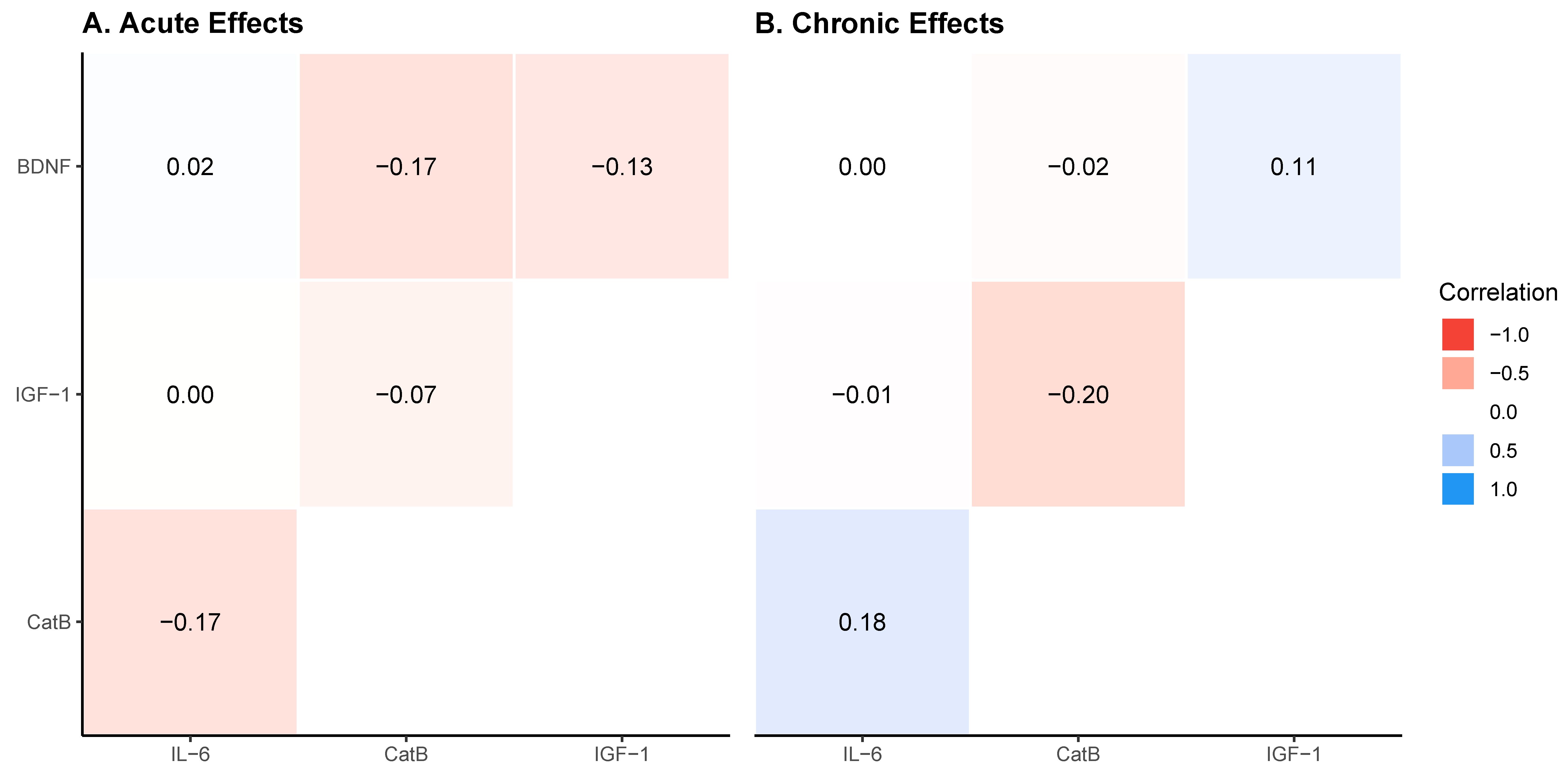

3.2. Acute and Chronic Biomarker Correlations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferguson, H.J.; Brunsdon, V.E.; Bradford, E.E. The Developmental Trajectories of Executive Function from Adolescence to Old Age. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, C.N.; Love, M.C.N.; Triebel, K. Normal Cognitive Aging. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2013, 29, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, E.W.; Corbett, N.J.; Roberts, J.G.; Ybarra, N.; Musial, T.F.; Simkin, D.; Molina-Campos, E.; Oh, K.-J.; Nielsen, L.L.; Ayala, G.D. Cognitive Aging Is Associated with Redistribution of Synaptic Weights in the Hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e1921481118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzola, P.; Melzer, T.; Pavesi, E.; Gil-Mohapel, J.; Brocardo, P.S. Exploring the Role of Neuroplasticity in Development, Aging, and Neurodegeneration. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobis, L.; Manohar, S.G.; Smith, S.M.; Alfaro-Almagro, F.; Jenkinson, M.; Mackay, C.E.; Husain, M. Hippocampal Volume across Age: Nomograms Derived from over 19,700 People in UK Biobank. NeuroImage Clin. 2019, 23, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colcombe, S.; Kramer, A.F. Fitness Effects on the Cognitive Function of Older Adults: A Meta-Analytic Study. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 14, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho-Junior, H.; Marzetti, E.; Calvani, R.; Picca, A.; Arai, H.; Uchida, M. Resistance Training Improves Cognitive Function in Older Adults with Different Cognitive Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, K.I.; Prakash, R.S.; Voss, M.W.; Chaddock, L.; Heo, S.; McLaren, M.; Pence, B.D.; Martin, S.A.; Vieira, V.J.; Woods, J.A. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Is Associated with Age-Related Decline in Hippocampal Volume. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 5368–5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, K.I.; Voss, M.W.; Prakash, R.S.; Basak, C.; Szabo, A.; Chaddock, L.; Kim, J.S.; Heo, S.; Alves, H.; White, S.M. Exercise Training Increases Size of Hippocampus and Improves Memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 3017–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, M.W.; Prakash, R.S.; Erickson, K.I.; Basak, C.; Chaddock, L.; Kim, J.S.; Alves, H.; Heo, S.; Szabo, A.; White, S.M. Plasticity of Brain Networks in a Randomized Intervention Trial of Exercise Training in Older Adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2010, 2, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinoff, A.; Herrmann, N.; Swardfager, W.; Liu, C.S.; Sherman, C.; Chan, S.; Lanctot, K.L. The Effect of Exercise Training on Resting Concentrations of Peripheral Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF): A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marosi, K.; Mattson, M.P. BDNF Mediates Adaptive Brain and Body Responses to Energetic Challenges. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 25, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.K.S.; Ho, C.S.H.; Tam, W.W.S.; Kua, E.H.; Ho, R.C.-M. Decreased Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Levels in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, G.; Beiser, A.S.; Choi, S.H.; Preis, S.R.; Chen, T.C.; Vorgas, D.; Au, R.; Pikula, A.; Wolf, P.A.; DeStefano, A.L. Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and the Risk for Dementia: The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szuhany, K.L.; Bugatti, M.; Otto, M.W. A Meta-Analytic Review of the Effects of Exercise on Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 60, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.D.; Hoffman, J.R.; Mangine, G.T.; Jajtner, A.R.; Townsend, J.R.; Beyer, K.S.; Wang, R.; La Monica, M.B.; Fukuda, D.H.; Stout, J.R. Comparison of High-Intensity vs. High-Volume Resistance Training on the BDNF Response to Exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 121, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marston, K.J.; Newton, M.J.; Brown, B.M.; Rainey-Smith, S.R.; Bird, S.; Martins, R.N.; Peiffer, J.J. Intense Resistance Exercise Increases Peripheral Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarrow, J.F.; White, L.J.; McCoy, S.C.; Borst, S.E. Training Augments Resistance Exercise Induced Elevation of Circulating Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 479, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, P.R.; Pansani, A.; Machado, F.; Andrade, M.; da Silva, A.C.; Scorza, F.A.; Cavalheiro, E.A.; Arida, R.M. Acute Strength Exercise and the Involvement of Small or Large Muscle Mass on Plasma Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Levels. Clinics 2010, 65, 1123–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goekint, M.; De Pauw, K.; Roelands, B.; Njemini, R.; Bautmans, I.; Mets, T.; Meeusen, R. Strength Training Does Not Influence Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 110, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, S.R.; Knicker, A.; Hollmann, W.; Bloch, W.; Strüder, H.K. Effect of Resistance Exercise on Serum Levels of Growth Factors in Humans. Horm. Metab. Res. 2010, 42, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Rosa, A.; Solana, E.; Corpas, R.; Bartrés-Faz, D.; Pallàs, M.; Vina, J.; Sanfeliu, C.; Gomez-Cabrera, M.C. Long-Term Exercise Training Improves Memory in Middle-Aged Men and Modulates Peripheral Levels of BDNF and Cathepsin B. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, H.Y.; Becke, A.; Berron, D.; Becker, B.; Sah, N.; Benoni, G.; Janke, E.; Lubejko, S.T.; Greig, N.H.; Mattison, J.A. Running-Induced Systemic Cathepsin B Secretion Is Associated with Memory Function. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Lou, K.; Hou, L.; Lu, Y.; Sun, L.; Tan, S.C.; Low, T.Y.; Kord-Varkaneh, H.; Pang, S. The Effect of Resistance Training on Serum Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 50, 102360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carro, E.; Nunez, A.; Busiguina, S.; Torres-Aleman, I. Circulating Insulin-like Growth Factor I Mediates Effects of Exercise on the Brain. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 2926–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte-Herbrüggen, O.; Nassenstein, C.; Lommatzsch, M.; Quarcoo, D.; Renz, H.; Braun, A. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α and Interleukin-6 Regulate Secretion of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Human Monocytes. J. Neuroimmunol. 2005, 160, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle, M.C.; Fernandez, M.L. Effects of Resistance Training on the Inflammatory Response. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2010, 4, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remmert, J.F.; Robinson, Z.P.; Pelland, J.C.; John, T.A.; Dinh, S.; Hinson, S.R.; Elkins, E.; Canteri, L.C.; Meehan, C.M.; Helms, E.R. Changes in Intraset Repetitions in Reserve Prediction Accuracy during Six Weeks of Bench Press Training in Trained Men. Percept. Mot. Skills 2023, 130, 2139–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, Z.; Macarilla, C.; Juber, M.; Cerminaro, R.; Benitez, B.; Pelland, J.; Remmert, J.; John, T.; Hinson, S.; Dinh, S. The Effect of Resistance Training Proximity to Failure on Muscular Adaptations and Longitudinal Fatigue in Trained Men. Int. J. Strength Cond. 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Sample Size Justification. Collabra Psychol. 2022, 8, 33267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refalo, M.C.; Remmert, J.F.; Pelland, J.C.; Robinson, Z.P.; Zourdos, M.C.; Hamilton, D.L.; Fyfe, J.J.; Helms, E.R. Accuracy of Intraset Repetitions-in-Reserve Predictions during the Bench Press Exercise in Resistance-Trained Male and Female Subjects. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2024, 38, e78–e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, J.; Fisher, J.; Giessing, J.; Gentil, P. Clarity in Reporting Terminology and Definitions of Set Endpoints in Resistance Training. Muscle Nerve 2017, 56, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helms, E.R.; Byrnes, R.K.; Cooke, D.M.; Haischer, M.H.; Carzoli, J.P.; Johnson, T.K.; Cross, M.R.; Cronin, J.B.; Storey, A.G.; Zourdos, M.C. RPE vs. Percentage 1RM Loading in Periodized Programs Matched for Sets and Repetitions. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, A.S.; Pollock, M.L. Practical Assessment of Body Composition. Phys. Sportsmed. 1985, 13, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.K.; Belcher, D.J.; Sousa, C.A.; Carzoli, J.P.; Visavadiya, N.P.; Khamoui, A.V.; Whitehurst, M.; Zourdos, M.C. Low-Volume Acute Multi-Joint Resistance Exercise Elicits a Circulating Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Response but Not a Cathepsin B Response in Well-Trained Men. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lira, F.S.; de Freitas, M.C.; Gerosa-Neto, J.; Cholewa, J.M.; Rossi, F.E. Comparison between Full-Body vs. Split-Body Resistance Exercise on the Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Immunometabolic Response. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 3094–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasevicius, T.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Silva-Batista, C.; de Souza Barros, T.; Aihara, A.Y.; Brendon, H.; Longo, A.R.; Tricoli, V.; de Almeida Peres, B.; Teixeira, E.L. Muscle Failure Promotes Greater Muscle Hypertrophy in Low-Load but Not in High-Load Resistance Training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, J.G.; Sardeli, A.V.; Dias, M.R.; Filho, J.E.; Campos, Y.; Sant’Ana, L.; Leitao, L.; Reis, V.; Wilk, M.; Novaes, J. Effects of Resistance Training to Muscle Failure on Acute Fatigue: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 1103–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourgouvelis, J.; Yielder, P.; Clarke, S.T.; Behbahani, H.; Murphy, B. You Can’t Fix What Isn’t Broken: Eight Weeks of Exercise Do Not Substantially Change Cognitive Function and Biochemical Markers in Young and Healthy Adults. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, K.J.; Brown, B.M.; Rainey-Smith, S.R.; Bird, S.; Wijaya, L.; Teo, S.Y.; Laws, S.M.; Martins, R.N.; Peiffer, J.J. Twelve Weeks of Resistance Training Does Not Influence Peripheral Levels of Neurotrophic Growth Factors or Homocysteine in Healthy Adults: A Randomized-Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 119, 2167–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiles, J.M.; Klemp, A.; Dolan, C.; Maharaj, A.; Huang, C.-J.; Khamoui, A.V.; Trexler, E.T.; Whitehurst, M.; Zourdos, M.C. Impact of Resistance Training Program Configuration on the Circulating Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Response. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, S.; Weimer, D.A.; Agans, S.C.; Bain, S.D.; Gross, T.S. Low-magnitude Mechanical Loading Becomes Osteogenic When Rest Is Inserted between Each Load Cycle. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2002, 17, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Ratamess, N.A. Hormonal Responses and Adaptations to Resistance Exercise and Training. Sports Med. 2005, 35, 339–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inyushkin, A.N.; Poletaev, V.S.; Inyushkina, E.M.; Kalberdin, I.S.; Inyushkin, A.A. Irisin/BDNF Signaling in the Muscle-Brain Axis and Circadian System: A Review. J. Biomed. Res. 2023, 38, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | 4–6 RIR (n = 8) | 1–3 RIR (n = 9) | 0–3 RIR (n = 8) | 0 RIR (n = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 22.50 ± 3.21 | 23.30 ± 3.09 | 21.33 ± 2.78 | 21.67 ± 2.08 |

| Height (cm) | 177.51 ± 5.75 | 174.95 ± 6.14 | 173.19 ± 6.23 | 168.03 ± 3.57 |

| Pre Body Mass (kg) | 81.33 ± 12.04 | 82.05 ± 12.82 | 78.24 ± 7.46 | 78.68 ± 14.37 |

| Post Body Mass (kg) | 82.61 ± 12.19 | 83.15 ± 13.14 | 79.33 ± 9.05 | 77.98 ± 15.49 |

| Δ Body Mass (kg) | 1.28 ± 1.64 | 1.10 ± 0.69 | 1.09 ± 2.87 | −0.70 ± 2.08 |

| Pre Sum of Skinfolds (mm) | 32.20 ± 8.98 | 31.40 ± 11.16 | 29.94 ± 9.52 | 31.50 ± 12.49 |

| Post Sum of Skinfolds (mm) | 35.32 ± 7.18 | 33.70 ± 13.51 | 33.44 ± 9.77 | 35.50 ± 14.00 |

| Δ Sum of Skinfolds (mm) | 3.12 ± 3.86 | 2.30 ± 3.70 | 3.50 ± 2.59 | 4.00 ± 5.29 |

| Pre Estimated Body Fat (%) | 15.42 ± 3.41 | 15.24 ± 4.60 | 14.35 ± 3.18 | 14.90 ± 5.34 |

| Post Estimated Body Fat (%) | 16.42 ± 3.02 | 15.94 ± 5.31 | 15.46 ± 3.36 | 16.15 ± 5.94 |

| Δ Estimated Body Fat (%) | 1.00 ± 1.25 | 0.70 ± 1.16 | 1.11 ± 0.82 | 1.25 ± 1.68 |

| Accessory-Exercise Adherence (%) | 75.2 ± 19.4 | 86.9 ± 15.3 | 100 ± 0.4 | 91.1 ± 10.0 |

| Marker | Model | Estimate | Mode | Lower_HDI | Upper_HDI | P_Null | P_ROPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDNF | Acute | Session | 1.26 | 0.37 | 1.97 | 99.75 | 63.60 |

| BDNF | Acute | Week | 0.69 | −0.42 | 1.73 | 87.05 | 17.24 |

| BDNF | Acute | Session × Week | 0.09 | −0.95 | 1.02 | 54.15 | 2.21 |

| BDNF | Acute | Session × RIR | −0.02 | −0.45 | 0.45 | 52.78 | 0.00 |

| BDNF | Acute | Week × RIR | 0.12 | −0.47 | 0.70 | 64.42 | 0.12 |

| BDNF | Acute | Session × Week × RIR | −0.51 | −1.00 | 0.07 | 96.40 | 0.00 |

| BDNF | Chronic | Time | 1.18 | −1.51 | 3.87 | 81.66 | 53.56 |

| BDNF | Chronic | Time × RIR | −0.43 | −1.71 | 0.95 | 71.08 | 0.00 |

| Marker | Model | Estimate | Mode | Lower_HDI | Upper_HDI | P_Null | P_ROPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatB | Acute | Session | 0.12 | −0.31 | 0.61 | 74.67 | 2.53 |

| CatB | Acute | Week | −0.17 | −0.68 | 0.32 | 73.58 | 0.00 |

| CatB | Acute | Session × Week | 1.17 | 0.48 | 1.92 | 99.83 | 94.39 |

| CatB | Acute | Session × RIR | 0.03 | −0.22 | 0.28 | 58.92 | 0.00 |

| CatB | Acute | Week × RIR | −0.12 | −0.38 | 0.18 | 77.41 | 0.00 |

| CatB | Acute | Session × Week × RIR | −0.34 | −0.75 | 0.03 | 96.88 | 0.00 |

| CatB | Chronic | Time | 0.32 | −0.72 | 1.38 | 72.91 | 27.65 |

| CatB | Chronic | Time × RIR | −0.29 | −0.84 | 0.25 | 87.53 | 0.00 |

| Marker | Model | Estimate | Mode | Lower_HDI | Upper_HDI | P_Null | P_ROPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGF-1 | Acute | Session | 7.02 | −6.25 | 20.38 | 85.27 | 55.25 |

| IGF-1 | Acute | Week | 7.27 | −4.55 | 20.11 | 89.42 | 60.39 |

| IGF-1 | Acute | Session × Week | 17.10 | −39.55 | 3.24 | 94.29 | 0.00 |

| IGF-1 | Acute | Session × RIR | 2.29 | −5.07 | 9.74 | 74.89 | 16.23 |

| IGF-1 | Acute | Week × RIR | 0.46 | −6.35 | 7.30 | 56.62 | 5.54 |

| IGF-1 | Acute | Session × Week × RIR | 8.07 | −3.19 | 19.67 | 92.38 | 65.43 |

| IGF-1 | Chronic | Time | −1.59 | −20.18 | 16.67 | 57.24 | 0.00 |

| IGF-1 | Chronic | Time × RIR | 6.38 | −2.86 | 16.08 | 92.25 | 54.60 |

| Marker | Model | Estimate | Mode | Lower_HDI | Upper_HDI | P_Null | P_ROPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | Acute | Session | 1.08 | 0.45 | 1.66 | 99.94 | 97.87 |

| IL-6 | Acute | Week | −0.05 | −0.77 | 0.75 | 51.93 | 0.00 |

| IL-6 | Acute | Session × Week | 0.73 | −0.23 | 1.63 | 93.55 | 71.88 |

| IL-6 | Acute | Session × RIR | −0.18 | −0.52 | 0.14 | 87.59 | 0.00 |

| IL-6 | Acute | Week × RIR | 0.26 | −0.17 | 0.67 | 88.30 | 18.93 |

| IL-6 | Acute | Session × Week × RIR | −0.04 | −0.55 | 0.46 | 54.73 | 0.00 |

| IL-6 | Chronic | Time | 1.06 | −1.88 | 3.73 | 77.25 | 66.27 |

| IL-6 | Chronic | Time × RIR | 0.35 | −1.17 | 1.89 | 69.74 | 47.38 |

| Model | x Variable | y Variable | r-Value | Lower_HDI | Upper_HDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | BDNF | IGF-1 | −0.14 | −0.47 | 0.22 |

| Acute | BDNF | CatB | −0.16 | −0.49 | 0.20 |

| Acute | BDNF | IL-6 | 0.01 | −0.35 | 0.36 |

| Acute | IGF-1 | CatB | −0.08 | −0.42 | 0.29 |

| Acute | IGF-1 | IL-6 | −0.00 | −0.35 | 0.35 |

| Acute | CatB | IL-6 | −0.16 | −0.50 | 0.19 |

| Chronic | BDNF | IGF-1 | 0.11 | −0.25 | 0.45 |

| Chronic | BDNF | CatB | −0.01 | −0.38 | 0.36 |

| Chronic | BDNF | IL-6 | 0.01 | −0.38 | 0.37 |

| Chronic | IGF-1 | CatB | −0.20 | −0.53 | 0.15 |

| Chronic | IGF-1 | IL-6 | −0.01 | −0.37 | 0.36 |

| Chronic | CatB | IL-6 | 0.19 | −0.18 | 0.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benitez, B.; Juber, M.C.; Macarilla, C.T.; Robinson, Z.P.; Pelland, J.C.; Remmert, J.F.; Hinson, S.R.; Visavadiya, N.P.; Zourdos, M.C. Effect of Proximity to Failure in Resistance Training on Circulating Levels of Neuroprotective Biomarkers. Biology 2025, 14, 1756. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121756

Benitez B, Juber MC, Macarilla CT, Robinson ZP, Pelland JC, Remmert JF, Hinson SR, Visavadiya NP, Zourdos MC. Effect of Proximity to Failure in Resistance Training on Circulating Levels of Neuroprotective Biomarkers. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1756. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121756

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenitez, Brian, Matthew C. Juber, Christian T. Macarilla, Zac P. Robinson, Joshua C. Pelland, Jacob F. Remmert, Seth R. Hinson, Nishant P. Visavadiya, and Michael C. Zourdos. 2025. "Effect of Proximity to Failure in Resistance Training on Circulating Levels of Neuroprotective Biomarkers" Biology 14, no. 12: 1756. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121756

APA StyleBenitez, B., Juber, M. C., Macarilla, C. T., Robinson, Z. P., Pelland, J. C., Remmert, J. F., Hinson, S. R., Visavadiya, N. P., & Zourdos, M. C. (2025). Effect of Proximity to Failure in Resistance Training on Circulating Levels of Neuroprotective Biomarkers. Biology, 14(12), 1756. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121756