Identification and Functional Characterization of the Leg-Enriched Chemosensory Protein PxylCSP9 in Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect and Tissue Collection

2.2. cDNA Library Construction and Function Annotation

2.3. Identification of Putative Chemosensory Genes

2.4. qRT-PCR

2.5. Heterologous Expression and Purification of Recombinant PxylCSP9 Protein

2.6. Fluorescence Competitive Binding Assays

2.7. Homology Modeling and Molecular Docking

3. Results

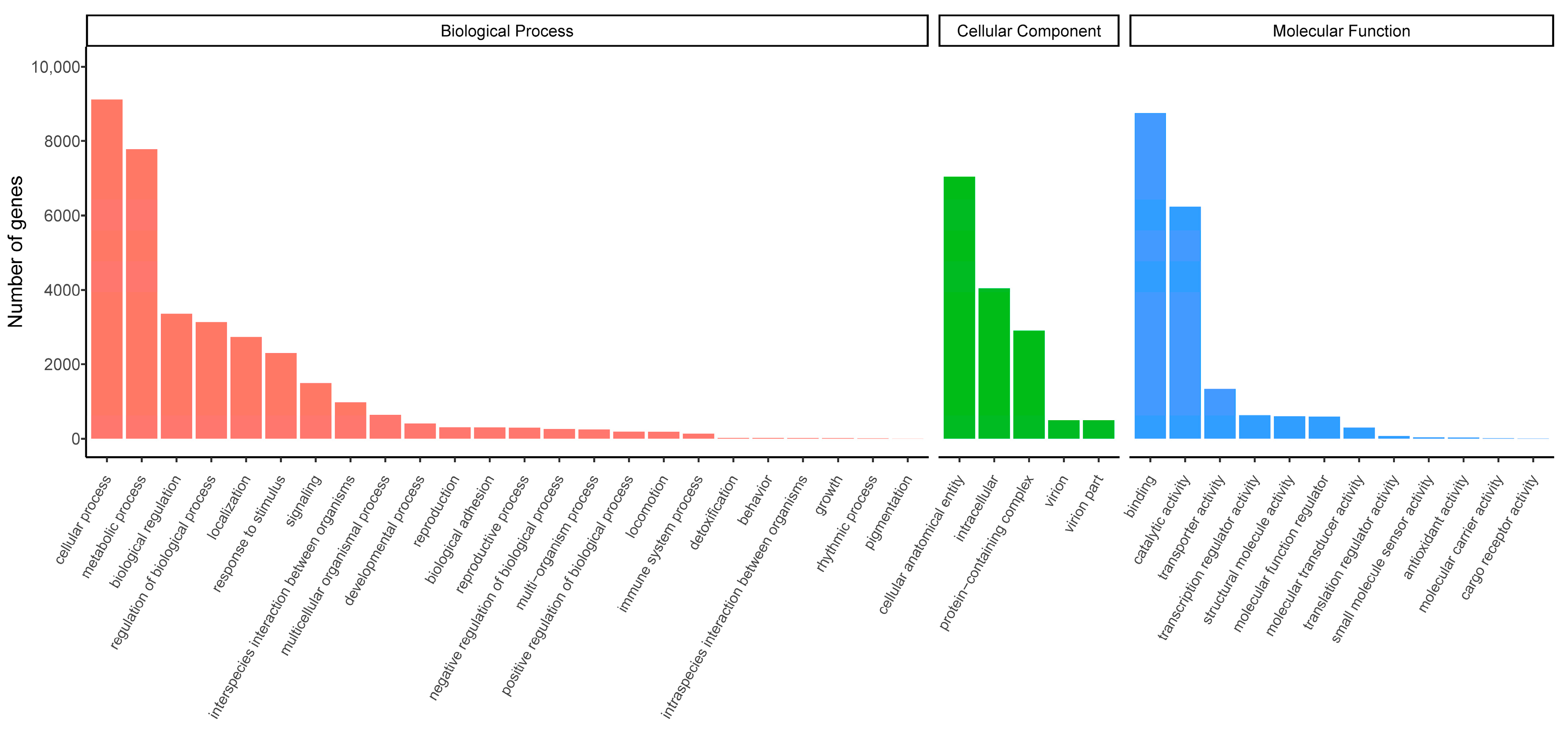

3.1. Overview of the Leg Transcriptome

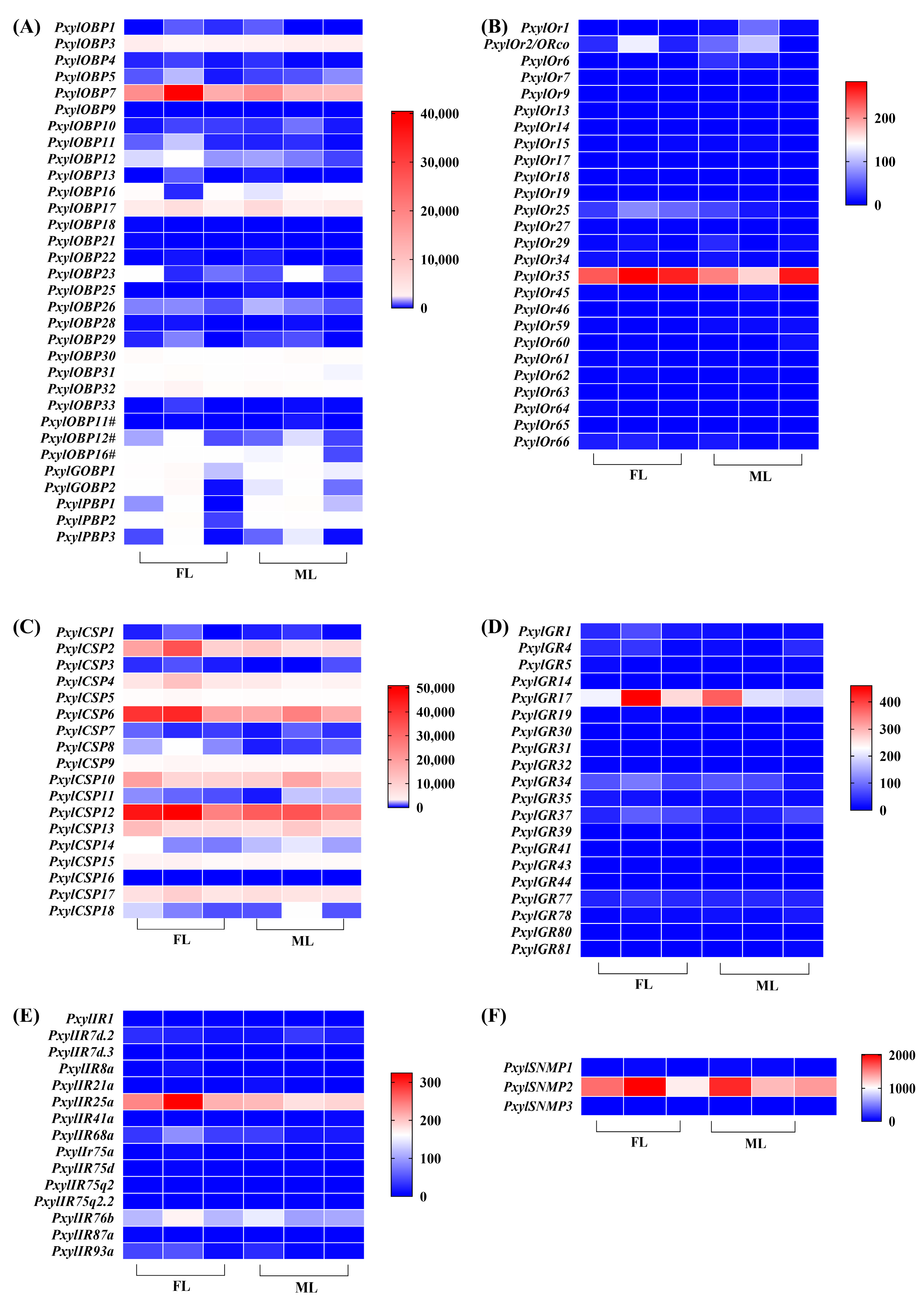

3.2. Identification of Putative Chemosensory-Related Genes in P. xylostella Legs

3.3. Expression Profiles of Chemosensory-Related Genes in P. xylostella Legs

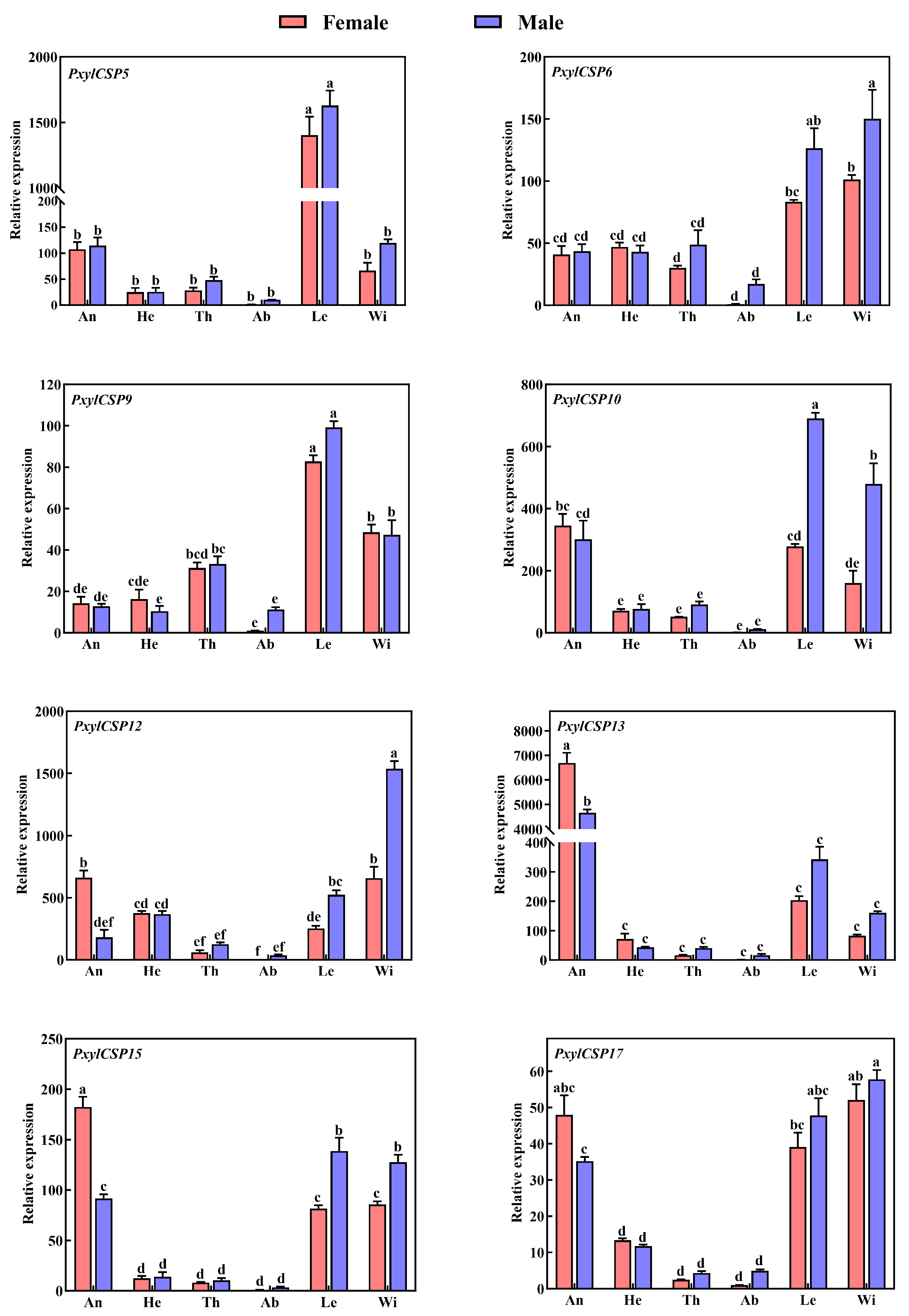

3.4. Tissue Expression Patterns of PxylCSPs

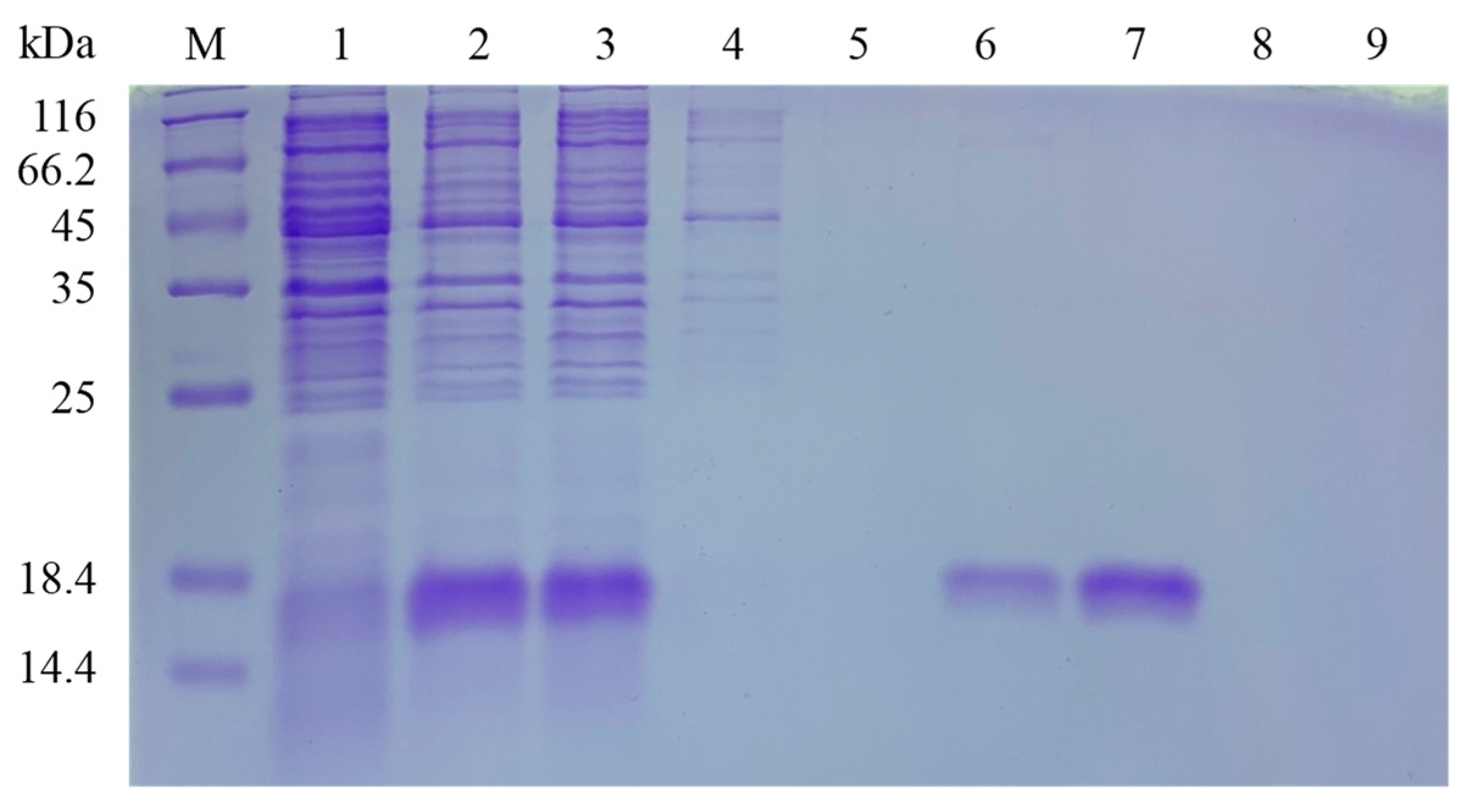

3.5. Cloning, Heterologous Expression, and Purification of PxylCSP9

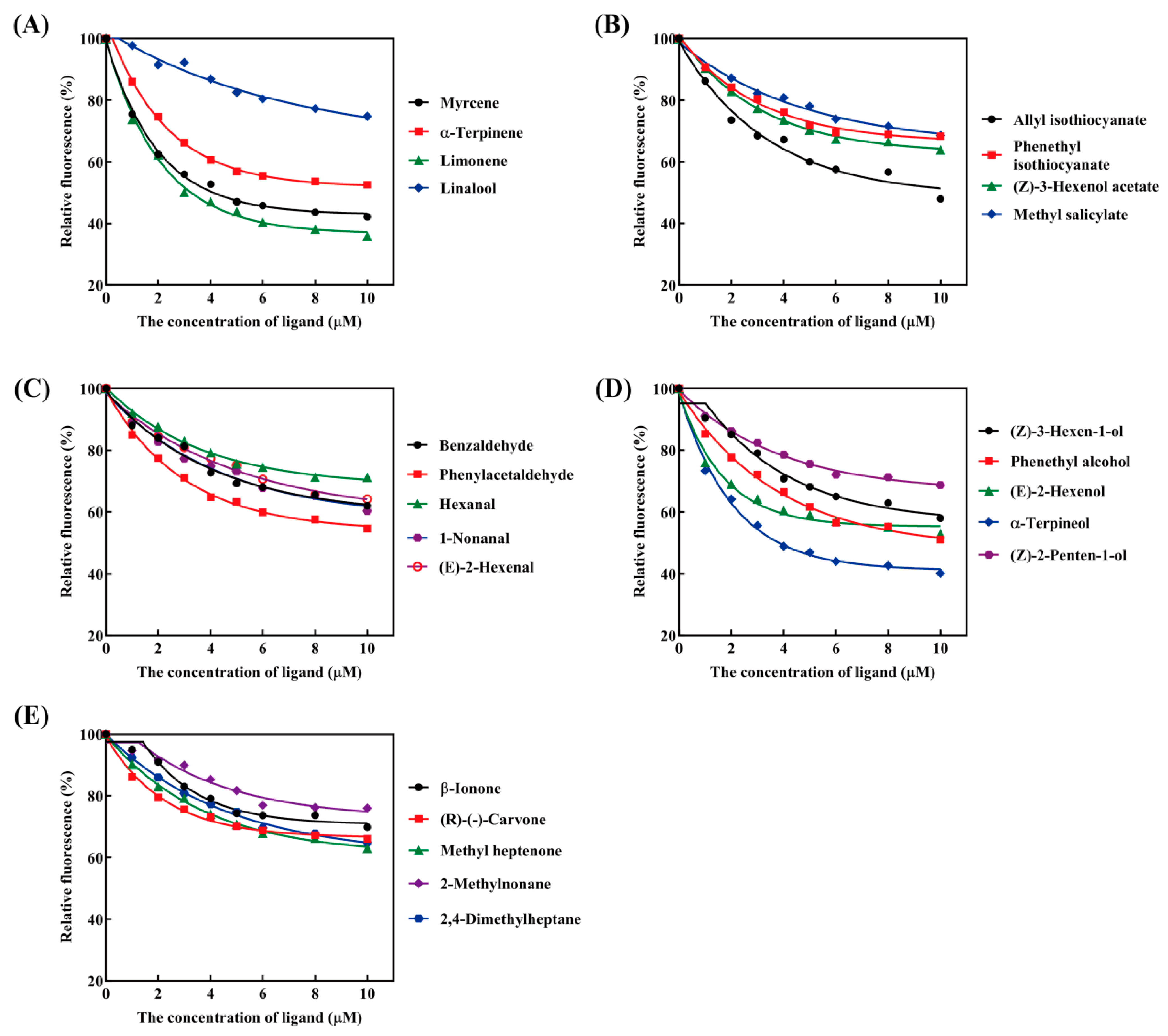

3.6. Characterization of PxylCSP9 Bound to Odorants

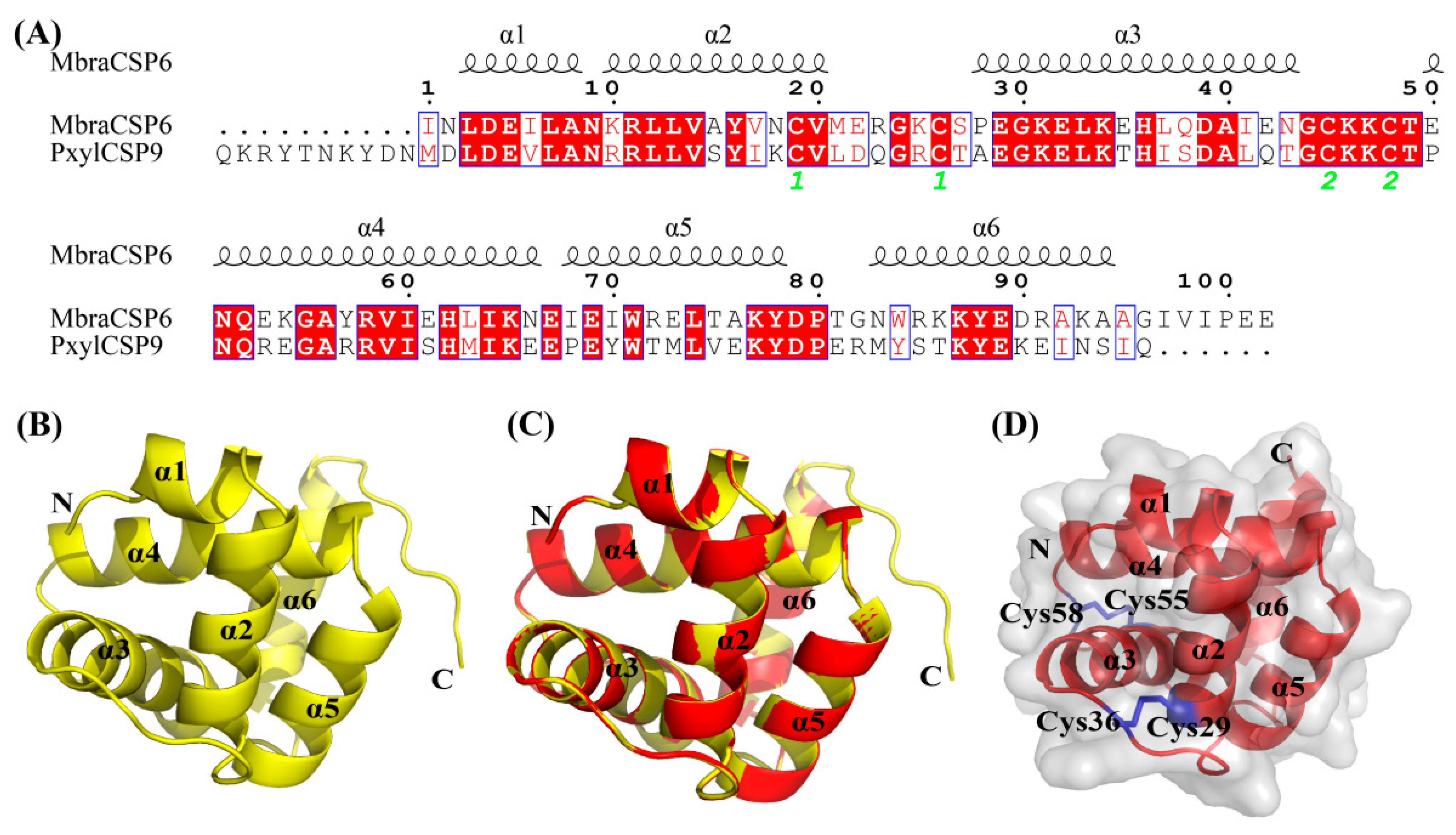

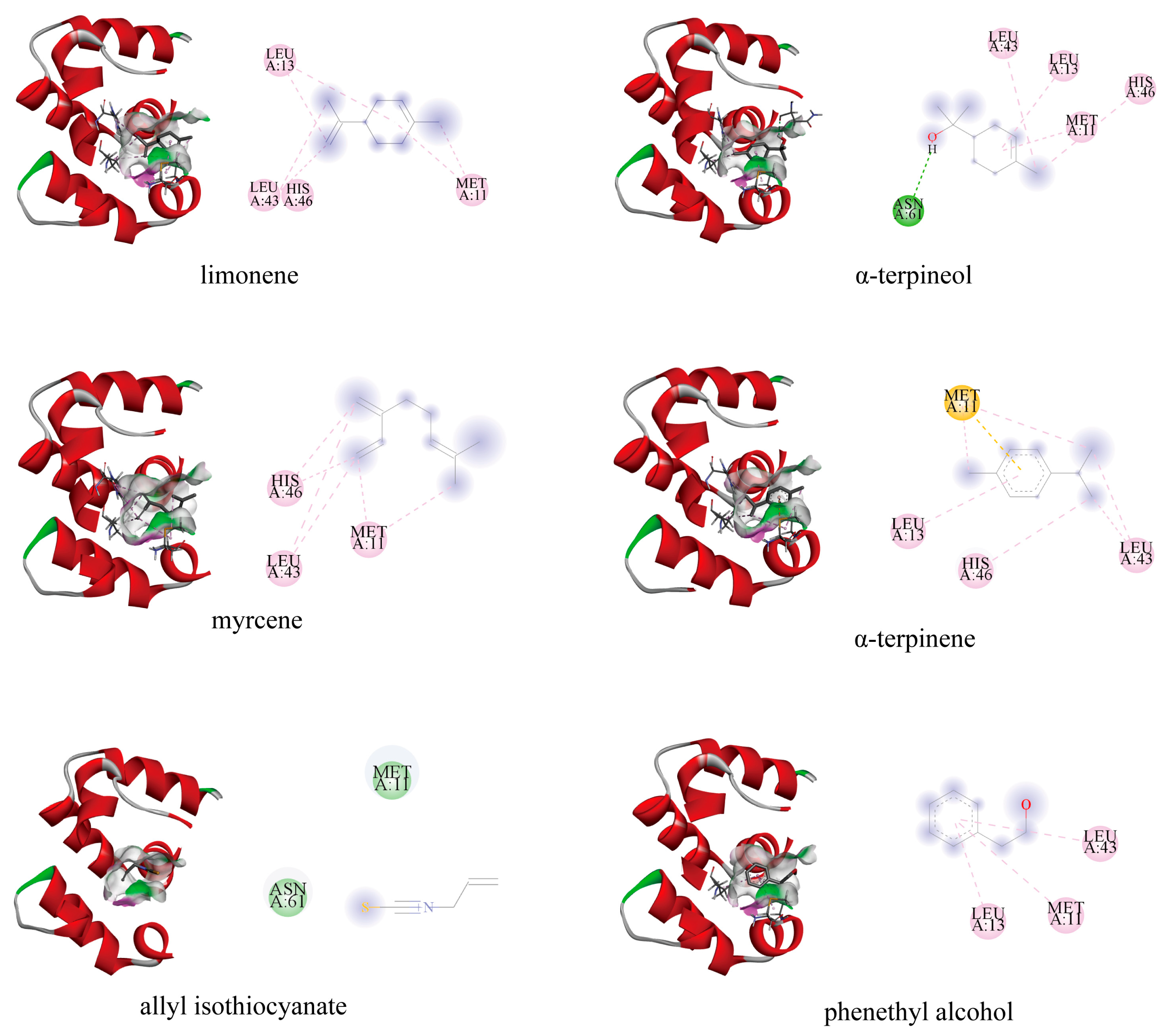

3.7. Modeling and Molecular Docking of PxylCSP9

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OBPs | Odorant binding proteins |

| CSPs | Chemosensory proteins |

| ORs | Olfactory receptors |

| GRs | Gustatory receptors |

| IRs | Ionotropic receptors |

| SNMPs | Sensory neuron membrane proteins |

| FPKM | Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads |

| IPTG | Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside |

| ORF | Open reading frame |

References

- Giron, D.; Dubreuil, G.; Bennett, A.; Dedeine, F.; Dicke, M.; Dyer, L.A.; Erb, M.; Harris, M.O.; Huguet, E.; Kaloshian, I.; et al. Promises and challenges in insect–plant interactions. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2018, 166, 319–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruyne, M.; Warr, C.G. Molecular and cellular organization of insect chemosensory neurons. Bioessays 2006, 28, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, H.; Hee, A.K.-W.; Jiang, H.B. Recent advancements in studies on chemosensory mechanisms underlying detection of semiochemicals in dacini fruit flies of economic importance (Diptera: Tephritidae). Insects 2021, 12, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, L.M.; Pickett, J.A.; Wadhams, L.J. Molecular studies in insect olfaction. Insect Mol. Biol. 2000, 9, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kefi, M.; Charamis, J.; Balabanidou, V.; Ioannidis, P.; Ranson, H.; Ingham, V.A.; Vontas, J. Transcriptomic analysis of resistance and short-term induction response to pyrethroids, in Anopheles coluzzii legs. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Li, Z.Q.; Bian, L.; Cai, X.M.; Luo, Z.X.; Zhang, Y.J.; Chen, Z.M. Identification and comparative study of chemosensory genes related to host selection by legs transcriptome analysis in the tea geometrid Ectropis obliqua. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, J.H. Host odor perception in phytophagous insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1986, 31, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cury, K.M.; Prud’homme, B.; Gompel, N. A short guide to insect oviposition: When, where and how to lay an egg. J. Neurogenet. 2019, 33, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.B.; Wei, Y.; Sun, L.; An, X.K.; Dhiloo, K.H.; Wang, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Khashaveh, A.; Gu, S.H.; Zhang, Y.J. Mouthparts enriched odorant binding protein AfasOBP11 plays a role in the gustatory perception of Adelphocoris fasciaticollis. J. Insect Physiol. 2019, 117, 103915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S.M.; Newland, P.L. Local movements evoked by chemical stimulation of the hind leg in the locust Schistocerca gregaria. J. Exp. Biol. 2000, 203, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Städler, E.; Reifenrath, K. Glucosinolates on the leaf surface perceived by insect herbivores: Review of ambiguous results and new investigations. Phytochem. Rev. 2009, 8, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, F.; Dahanukar, A.; Weiss, L.A.; Kwon, J.Y.; Carlson, J.R. The molecular and cellular basis of taste coding in the legs of Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 7148–7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, N.; Thiery, D.; Städler, E. Oviposition by Lobesia botrana is stimulated by sugars detected by contact chemoreceptors. Physiol. Entomol. 2006, 31, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; van Loon, J.J.A.; Wang, C.Z. Tarsal taste neuron activity and proboscis extension reflex in response to sugars and amino acids in Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner). J. Exp. Biol. 2010, 213, 2889–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Gracia, A.; Vieira, F.G.; Rozas, J. Molecular evolution of the major chemosensory gene families in insects. Heredity 2009, 103, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, W.S. Odorant reception in insects: Roles of receptors, binding proteins, and degrading enzymes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013, 58, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheelwright, M.; Whittle, C.R.; Riabinina, O. Olfactory systems across mosquito species. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 383, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelosi, P.; Iovinella, I.; Zhu, J.; Wang, G.R.; Dani, F.R. Beyond chemoreception: Diverse tasks of soluble olfactory proteins in insects. Biol. Rev. 2018, 93, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, J.; Pregitzer, P.; Breer, H.; Krieger, J. Access to the odor world: Olfactory receptors and their role for signal transduction in insects. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 485–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Q.; Miao, C.L.; Han, W.K.; Hou, W.; Yang, K.; Hansson, B.S.; Peng, Y.C.; Guo, J.M.; et al. The molecular basis of host selection in a crucifer-specialized moth. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 4476–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, W.D.; Cayirlioglu, P.; Grunwald Kadow, I.; Vosshall, L.B. Two chemosensory receptors together mediate carbon dioxide detection in Drosophila. Nature 2007, 445, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.S.; Wang, P.C.; Ning, C.; Yang, K.; Li, G.C.; Cao, L.L.; Huang, L.Q.; Wang, C.Z. The larva and adult of Helicoverpa armigera use differential gustatory receptors to sense sucrose. Elife 2024, 12, RP91711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.J.; Ning, C.; Guo, H.; Jia, Y.Y.; Huang, L.Q.; Qu, M.J.; Wang, C.Z. A gustatory receptor tuned to D-fructose in antennal sensilla chaetica of Helicoverpa armigera. Insect Biochem. Molec. 2015, 60, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L.A.; Dahanukar, A.; Kwon, J.Y.; Banerjee, D.; Carlson, J.R. The molecular and cellular basis of bitter taste in Drosophila. Neuron 2011, 69, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croset, V.; Rytz, R.; Cummins, S.F.; Budd, A.; Brawand, D.; Kaessmann, H.; Gibson, T.J.; Benton, R. Ancient protostome origin of chemosensory ionotropic glutamate receptors and the evolution of insect taste and olfaction. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicher, D.; Miazzi, F. Functional properties of insect olfactory receptors: Ionotropic receptors and odorant receptors. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 383, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rytz, R.; Croset, V.; Benton, R. Ionotropic receptors (IRs): Chemosensory ionotropic glutamate receptors in Drosophila and beyond. Insect Biochem. Molec. 2013, 43, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, R.G.; Miller, N.E.; Litvack, R.; Fandino, R.A.; Sparks, J.; Staples, J.; Friedman, R.; Dickens, J.C. The insect SNMP gene family. Insect Biochem. Molec. 2009, 39, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassau, S.; Krieger, J. The role of SNMPs in insect olfaction. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 383, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.L.; Xu, K.; Ma, W.H.; Su, W.T.; Tai, M.M.; Zhao, H.T.; Jiang, Y.S.; Li, X.C. Contact chemosensory genes identified in leg transcriptome of Apis cerana cerana (Hymenoptera: Apidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 2015–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.B.; Zhang, Y.Y.; An, X.K.; Wang, Q.; Khashaveh, A.; Gu, S.H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.J. Identification of leg chemosensory genes and sensilla in the Apolygus lucorum. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.R.; Tong, N.; Li, Y.; Guo, J.M.; Lu, M.; Liu, X.L. Foreleg transcriptomic analysis of the chemosensory gene families in Plagiodera versicolora (coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Insects 2022, 13, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.F.; Zhang, S.; Cui, J.J.; Wang, D.J.; Wang, C.Y.; Luo, J.Y.; Lv, L.M.; Ma, Y. Functional characterizations of one odorant binding protein and three chemosensory proteins from Apolygus lucorum (Meyer-Dur)(Hemiptera: Miridae) legs. J. Insect Physiol. 2013, 59, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, S.; Amrein, H. A putative Drosophila pheromone receptor expressed in male-specific taste neurons is required for efficient courtship. Neuron 2003, 39, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, M.; Keddie, A.B.; Dosdall, L.M. Biological control of the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella: A review. Biocontrol Sci. Techn. 2005, 15, 763–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, M.; Farooq, M.; Nasim, W.; Akram, W.; Khan, F.Z.A.; Jaleel, W.; Zhu, X.; Yin, H.C.; Li, S.Z.; Fahad, S.; et al. Environment polluting conventional chemical control compared to an environmentally friendly IPM approach for control of diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L.), in China: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2017, 24, 14537–14550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renwick, J.A.A.; Haribal, M.; Gouinguené, S.; Städler, E. Isothiocyanates stimulating oviposition by the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella. J. Chem. Ecol. 2006, 32, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.Y.; Sønderby, I.E.; Halkier, B.A.; Jander, G.; de Vos, M. Non-volatile intact indole glucosinolates are host recognition cues for ovipositing Plutella xylostella. J. Chem. Ecol. 2009, 35, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.J.; Zheng, L.S.; Huang, Y.P.; Xu, W.; You, M.S. Identification and characterization of odorant binding proteins in the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella. Insect Sci. 2021, 28, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Cao, D.P.; Wang, G.R.; Liu, Y. Identification of genes involved in chemoreception in Plutella xyllostella by antennal transcriptome analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Gong, X.L.; Li, G.C.; Huang, L.Q.; Ning, C.; Wang, C.Z. A gustatory receptor tuned to the steroid plant hormone brassinolide in Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Elife 2020, 9, e64114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.Y.; Xu, W.; Dong, S.L.; Zhu, J.Y.; Xu, Y.X.; Anderson, A. Genome-wide analysis of ionotropic receptor gene repertoire in Lepidoptera with an emphasis on its functions of Helicoverpa armigera. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol 2018, 99, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.J.; Xu, W.; Chen, Q.M.; Sun, L.N.; Anderson, A.; Xia, Q.Y.; Papanicolaou, A. A phylogenomics approach to characterizing sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMPs) in Lepidoptera. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol 2020, 118, 103313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, G.V.P.; Guerrero, A. Behavioral responses of the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella, to green leaf volatiles of Brassica oleracea Subsp. capitata. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 6025–6029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.Z.; Ma, L.; Li, X.F.; Chang, L.; Liu, Q.Z.; Song, C.F.; Zhao, J.Y.; Qie, X.T.; Deng, C.P.; Wang, C.Z.; et al. Identification and evaluation of cruciferous plant volatiles attractive to Plutella xylostella L. (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 5270–5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, D.T.; Thi, H.L.; Vang, L.V.; Thy, T.T.; Yamamoto, M.; Ando, T. Mass trapping of the diamondback moth (Plutella xylostella L.) by a combination of its sex pheromone and allyl isothiocyanate in cabbage fields in southern Vietnam. J. Pestic. Sci. 2024, 49, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.Y.; Li, Y.Y.; Shao, K.M.; Li, S.L.; Guan, Y.; Guo, H.; Chen, L. Electrophysiological responses and field attractants of Plutella xylostella adults to volatiles from Brassica oleracea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 8925–8934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.X.; Ling, B.; Chen, S.Y.; Liang, G.W.; Pang, X.F. Repellent and oviposition deterrent activities of the essential oil from Mikania micrantha and its compounds on Plutella xylostella. Insect Sci. 2004, 11, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.A.; Nissinen, A.; Holopainen, J.K. Response of Plutella xylostella and its parasitoid Cotesia plutellae to volatile compounds. J. Chem. Ecol. 2005, 31, 1969–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.Z.; Wang, Z.Y.; Ma, L.; Song, C.F.; Zhao, J.Y.; Wang, C.Z.; Hao, C. Electroantennogram and behavioural responses of Plutella xylostella to volatiles from the non-host plant Mentha spicata. J. Appl. Entomol. 2023, 147, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, V.; Knapek, S.; Arai, S.; Hartl, M.; Kohsaka, H.; Sirigrivatanawong, P.; Abe, A.; Hashimoto, K.; Tanimoto, H. Functional dissociation in sweet taste receptor neurons between and within taste organs of Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.F.; Slone, J.D.; Rokas, A.; Berger, S.L.; Liebig, J.; Ray, A.; Reinberg, D.; Zwiebel, L.J. Phylogenetic and transcriptomic analysis of chemosensory receptors in a pair of divergent ant species reveals sex-specific signatures of odor coding. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R.M.; Carlson, J.R. Drosophila chemoreceptors: A molecular interface between the chemical world and the brain. Trends Genet. 2015, 31, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Guo, J.M.; Wei, Z.Q.; Zhang, X.T.; Liu, S.R.; Guo, H.F.; Dong, S.L. Identification and sex expression profiles of olfactory-related genes in Mythimna loreyi based on antennal transcriptome analysis. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2022, 25, 101934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X.; Qi, Z.H.; Chen, J.; Wang, F.L.; Gui, L.Y.; Zhang, G.H. Molecular characterization of chemosensory protein genes in Bactrocera minax (Diptera: Tephritidae). Entomol. Res. 2021, 51, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.F.; Bi, Y.L.; Chi, H.P.; Fang, Q.; Lu, Z.Z.; Wang, F.; Ye, G.Y. Identification and expression analysis of odorant-binding and chemosensory protein genes in virus vector Nephotettix cincticeps. Insects 2022, 13, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.L.; Luo, Q.; Zhong, G.H.; Rizwan-ul-Haq, M.; Hu, M.Y. Molecular characterization and expression pattern of four chemosensory proteins from diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). J. Biochem. 2010, 148, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halkier, B.A.; Gershenzon, J. Biology and biochemistry of glucosinolates. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 303–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ômura, H.; Honda, K.; Hayashi, N. Chemical and chromatic bases for preferential visiting by the cabbage butterfly, Pieris rapae, to rape flowers. J. Chem. Ecol. 1999, 25, 1895–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, K.; ÔMura, H.; Hayashi, N. Identification of floral volatiles from Ligustrum japonicum that stimulate flower-visiting by cabbage butterfly, Pieris rapae. J. Chem. Ecol. 1998, 24, 2167–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.J.; Lin, S.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.X.; Zhao, J.W.; Gu, X.J.; Wei, H. Electroantennogram responses to plant volatiles associated with fenvalerate resistance in the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2018, 111, 1354–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.L. Structural insights into Cydia pomonella pheromone binding protein 2 mediated prediction of potentially active semiochemicals. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cui, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.P.; Wang, G.R.; Zhou, Q. Identification and functional analysis of a chemosensory protein from Bactrocera minax (Diptera: Tephritidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 3479–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Chemosensory-Related Genes | Number of Genes in the Legs | Number of Newly Found Genes | Number of Reported Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Odorant binding protein (OBP) genes | 32 | 0 | 39 [40,41] |

| Chemosensory protein (CSP) genes | 18 | 3 | 15 [41] |

| Odorant receptor (OR) genes | 26 | 7 | 59 [20] |

| Gustatory receptor (GR) genes | 20 | 2 | 67 [42] |

| Ionotropic receptor (IR) genes | 15 | 0 | 36 [43] |

| Sensory neuron membrane protein (SNMP) genes | 3 | 0 | 3 [41,44] |

| Ligands | IC50 (μM) | Ki (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Monoterpenes | ||

| Myrcene b | 4.92 ± 0.65 | 4.15 |

| α-Terpinene b | 9.10 ± 0.31 | 7.68 |

| Limonene b | 3.70 ± 0.13 | 3.12 |

| Linalool b | 30.89 ± 8.71 | 26.07 |

| Esters | ||

| Allyl isothiocyanate a | 9.62 ± 0.58 | 8.12 |

| Phenethyl Isothiocyanate | 27.98 ± 1.53 | 23.61 |

| (Z)-3-Hexenol acetate a | 21.02 ± 0.65 | 17.73 |

| Methyl salicylate | 31.85 ± 4.23 | 26.88 |

| Aldehydes | ||

| Benzaldehyde | 18.97 ± 1.64 | 16.01 |

| Phenylacetaldehyde | 11.98 ± 0.72 | 10.11 |

| Hexanal a | 33.21 ± 1.34 | 28.04 |

| 1-Nonanal a | 18.82 ± 1.16 | 15.88 |

| (E)-2-Hexenal a | 21.49 ± 0.41 | 18.10 |

| Alcohols | ||

| (Z)-2-Penten-1-ol | 30.79 ± 3.94 | 25.95 |

| (Z)-3-Hexen-1-ol a | 13.90 ± 0.32 | 11.73 |

| Phenethyl alcohol a | 9.90 ± 0.43 | 8.34 |

| (E)-2-Hexenol a | 11.97 ± 0.91 | 10.08 |

| α-Terpineol | 4.49 ± 0.14 | 3.80 |

| Ketones | ||

| β-Ionone | 26.51 ± 2.53 | 22.37 |

| (R)-(-)-Carvone b | 34.64 ± 6.62 | 29.19 |

| Methyl heptenone | 20.10 ± 1.98 | 16.96 |

| Alkanes | ||

| 2,4-Dimethylheptane b | 20.62 ± 0.46 | 17.40 |

| 2-Methylnonane b | 36.53 ± 4.30 | 30.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fu, S.; Li, F.; Yan, X.; Hao, C. Identification and Functional Characterization of the Leg-Enriched Chemosensory Protein PxylCSP9 in Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Biology 2025, 14, 1746. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121746

Fu S, Li F, Yan X, Hao C. Identification and Functional Characterization of the Leg-Enriched Chemosensory Protein PxylCSP9 in Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Biology. 2025; 14(12):1746. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121746

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Shuhui, Fangyuan Li, Xizhong Yan, and Chi Hao. 2025. "Identification and Functional Characterization of the Leg-Enriched Chemosensory Protein PxylCSP9 in Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae)" Biology 14, no. 12: 1746. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121746

APA StyleFu, S., Li, F., Yan, X., & Hao, C. (2025). Identification and Functional Characterization of the Leg-Enriched Chemosensory Protein PxylCSP9 in Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Biology, 14(12), 1746. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121746