How Accurate Are Population Predictions? Wind Farms and Egyptian Vultures as a Case Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Supplementary Feeding

2.2. Simulations

3. Results

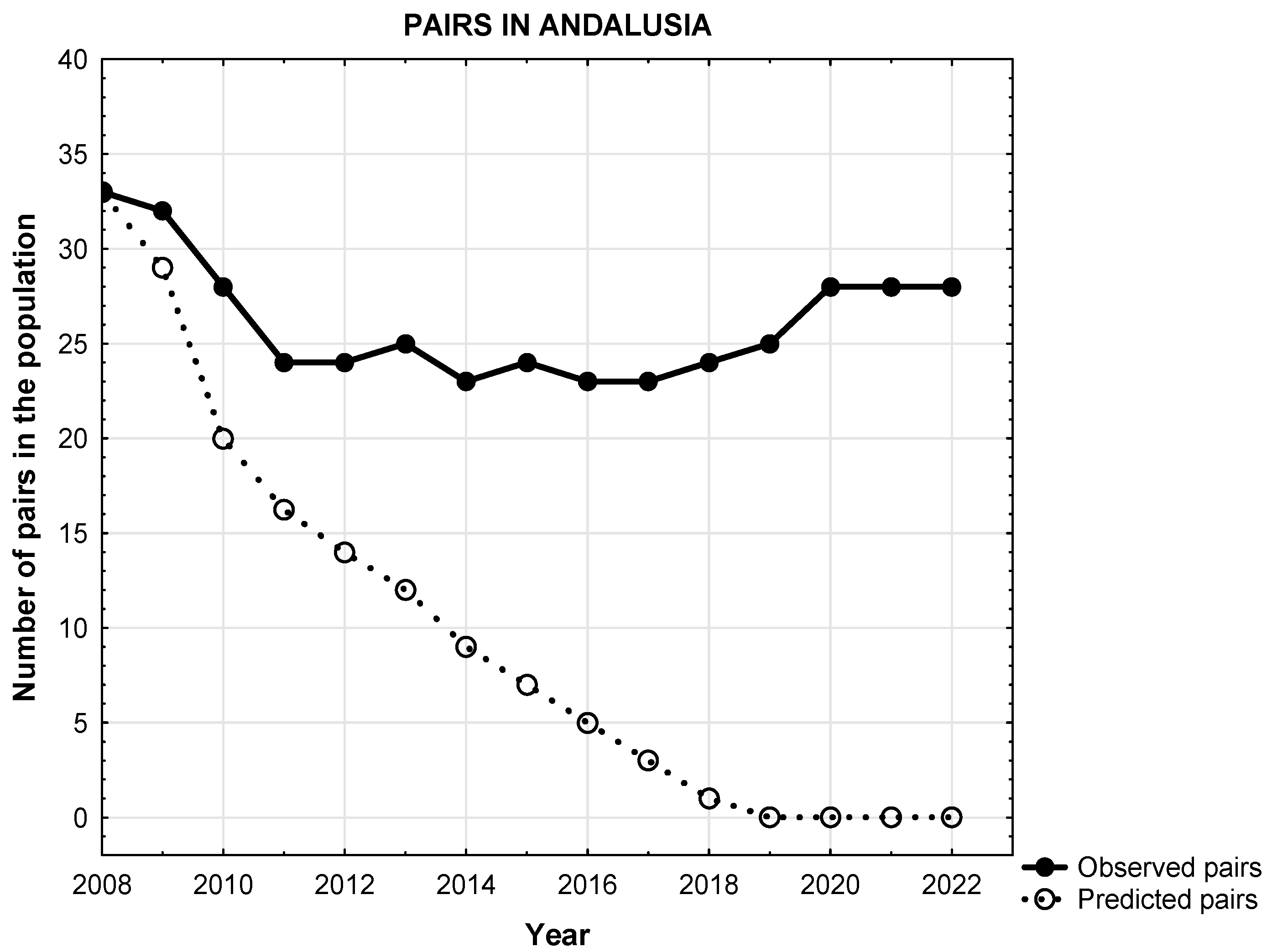

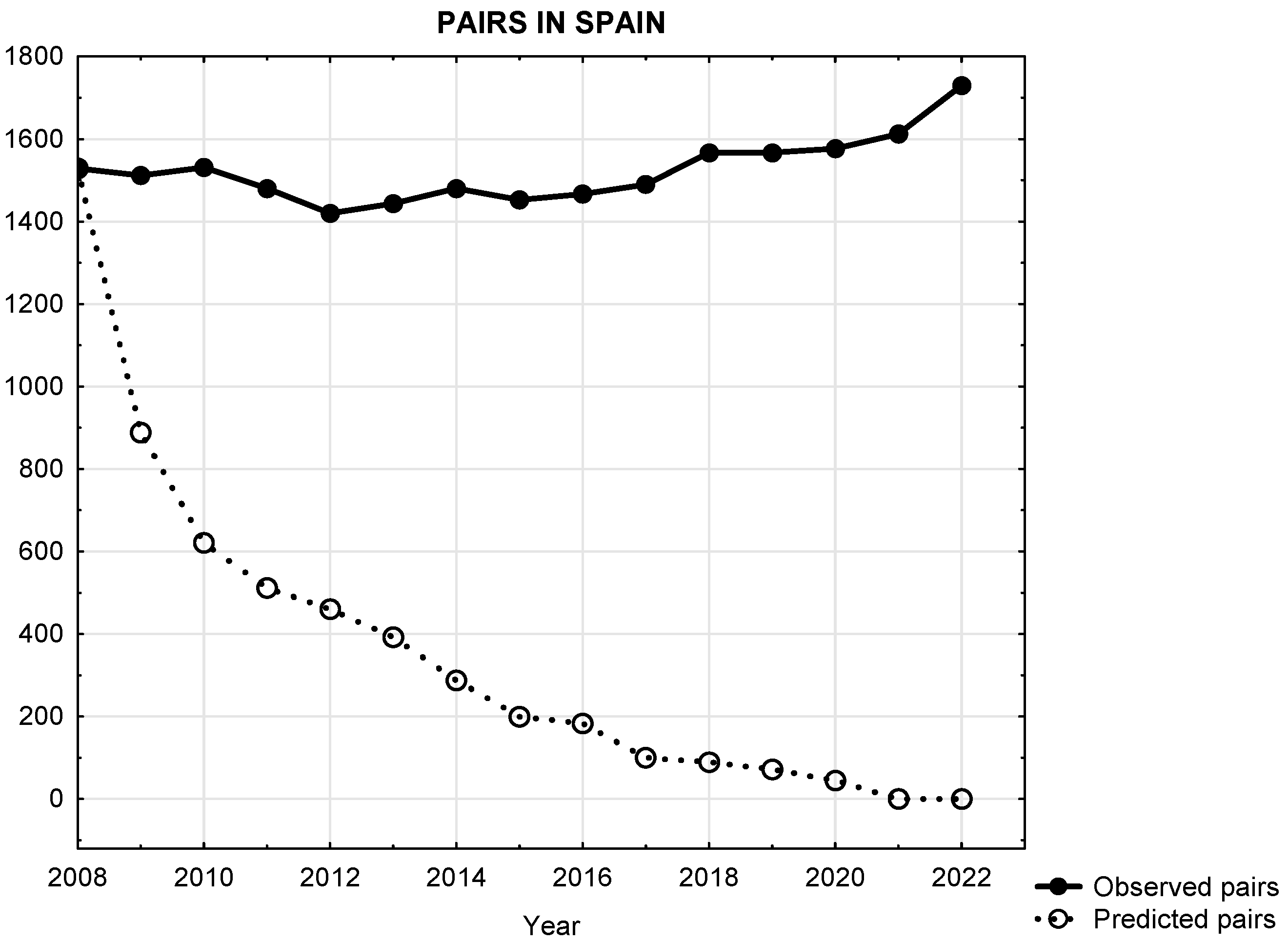

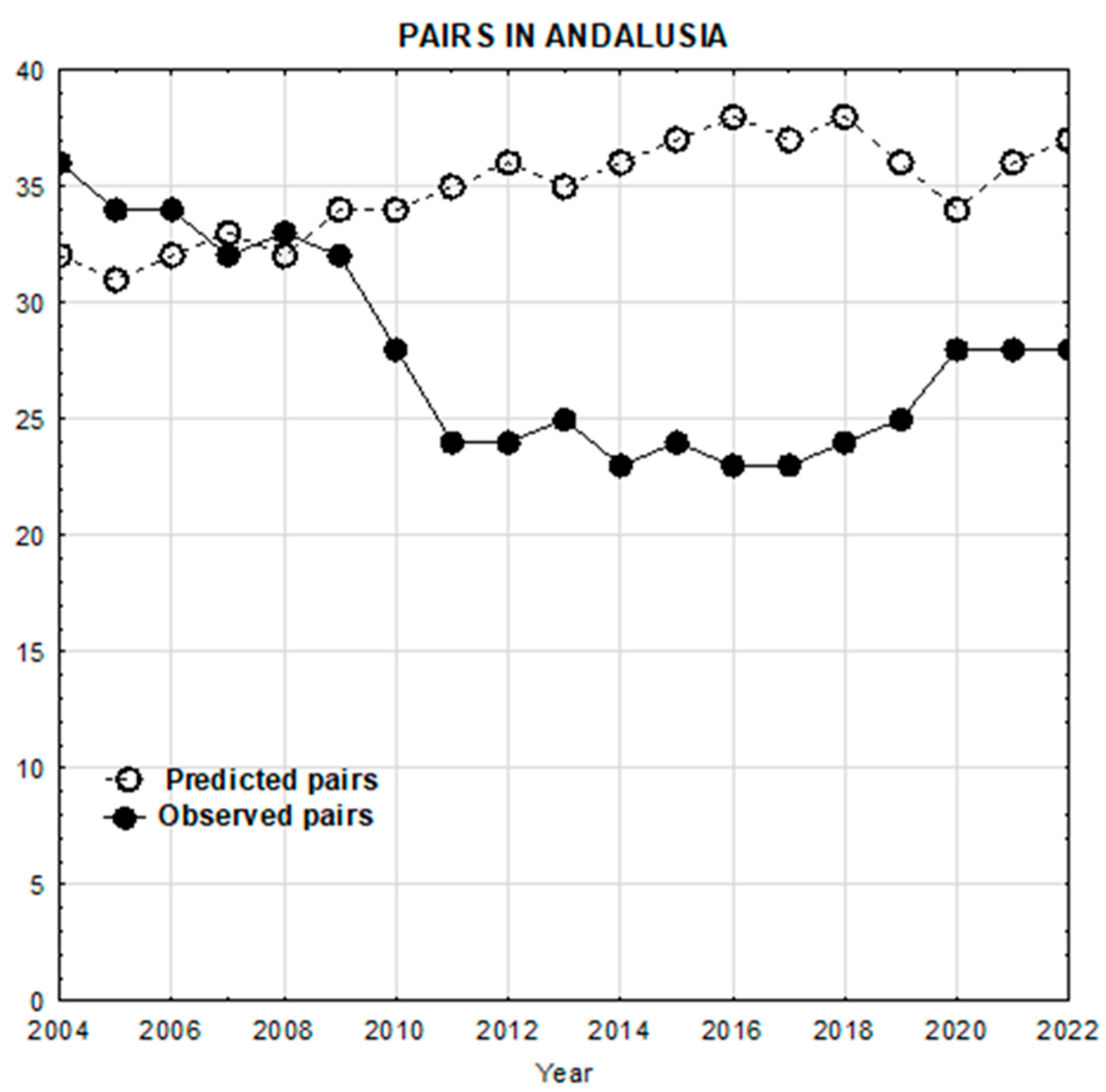

3.1. Predicted Versus Observed Population Trajectories of Egyptian Vultures Subsection

3.2. Change in Baseline Conditions

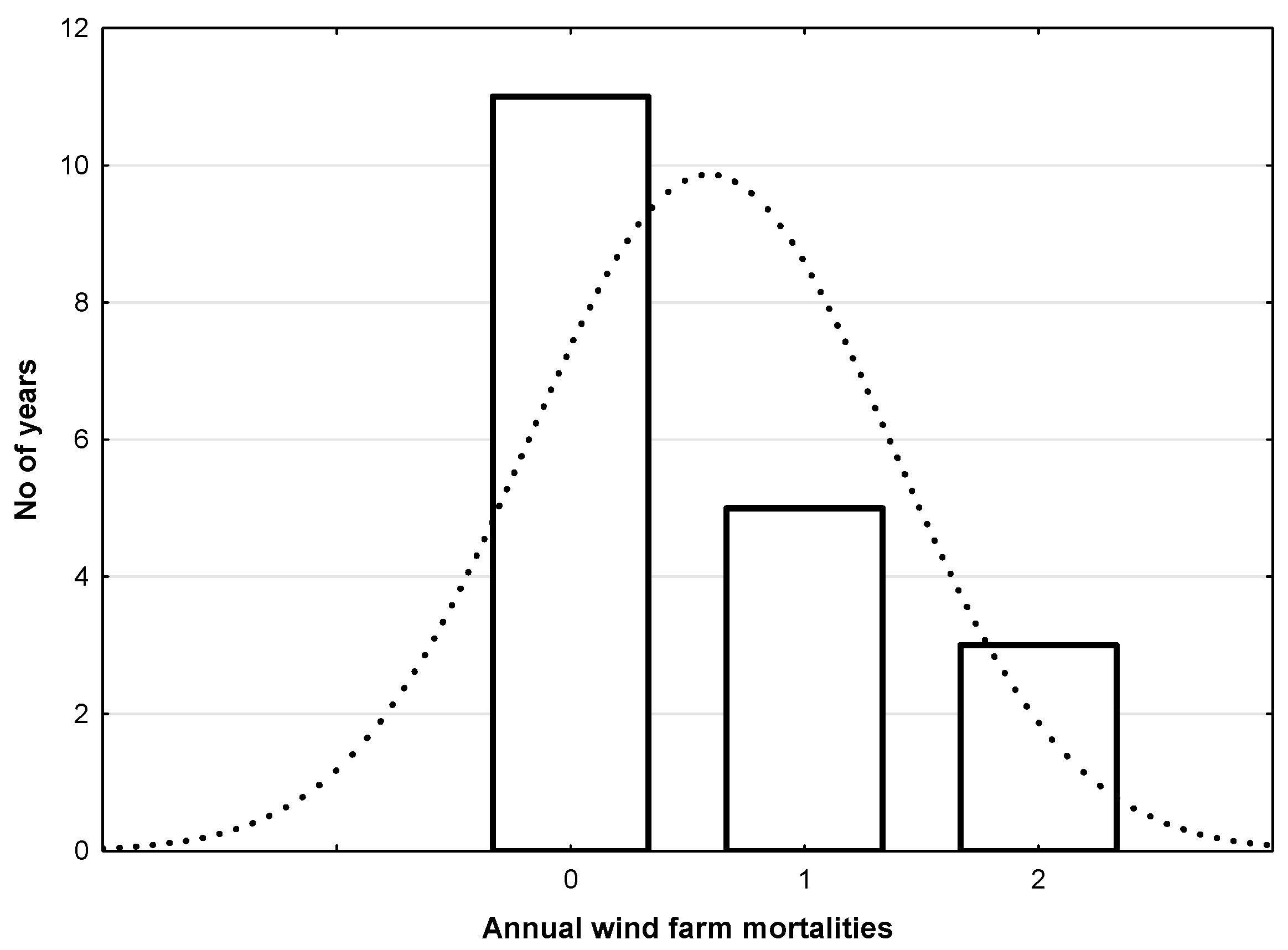

3.2.1. Mortality by Wind Farms

3.2.2. Productivity

3.2.3. Mortality from Poisons

3.3. Distribution of Simulated Demographic Stochasticity and Environmental Variability

3.4. Estimation of the Number of Pairs in Risk Areas

3.5. Simulation Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brook, B.W.; O′Grady, J.J.; Chapman, A.P.; Burgman, M.A.; Akçakaya, H.R.; Frankham, R. Predictive accuracy of population viability analysis in conservation biology. Nature 2000, 404, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, B.W.; Lim, L.; Harden, R.; Frankham, R. Does population viability analysis software predict the behaviour of real populations? A retrospective study on the Lord Howe Island wood hen Tricholimnas sylvestris (Sclater). Biol. Conserv. 1997, 82, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, T.; Mace, G.M.; Hudson, E.; Possingham, H. The use and abuse of population viability analysis. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001, 16, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, M.S. Population viability analysis. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1992, 23, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beissinger, S.R.; Westphal, M.I. On the use of demographic models of population viability in endangered species management. J. Wildl. Manag. 1998, 62, 821–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.; Moller, H. Can PVA models using computer packages offer useful conservation advice? Sooty shearwaters Puffinus griseus in New Zealand as a case study. Biol. Conserv. 1995, 73, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.L. The reliability of using population viability analysis for risk classification of species. Conserv. Biol. 1995, 9, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, M.J.; Pascual, M.A. The analysis of population persistence: An outlook on the practice of viability analysis. In Conservation Biology: For the Coming Decade; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 4–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, D. Is it meaningful to estimate a probability of extinction? Ecology 1999, 80, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrete, M.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A.; Benítez, J.R.; Lobón, M.; Donázar, J.A. Large scale risk-assessment of wind-farms on population viability of a globally endangered long-lived raptor. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 2954–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://issuu.com/aeeolica/docs/anuarioeolico2020_aee (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Xu, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; Tang, J.; Nguyen, M.; Cui, S. Identifying the trade-offs between climate change mitigation and adaptation in urban land use planning: An empirical study in a coastal city. Environ. Int. 2019, 133, 105162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, M.R.; Rezk, H.; Mustafa, R.J.; Al-Dhaifallah, M. Evaluating the environmental impacts and energy performance of a wind farm system utilizing the life-cycle assessment method: A practical case study. Energies 2019, 12, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidur, R.; Rahim, N.A.; Islam, M.R.; Solangi, K.H. Environmental impact of wind energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2423–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucas, M.; Janss, G.F.; Whitfield, D.P.; Ferrer, M. Collision fatality of raptors in wind farms does not depend on raptor abundance. J. Appl. Ecol. 2008, 45, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; De Lucas, M.; Janss, G.F.E.; Casado, E.; Muñoz, A.R.; Bechard, M.; Calabuig, C.P. Weak relationship between risk assessment studies and recorded mortality in wind farms. J. Appl. Ecol. 2012, 49, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.S.; Bilal, M.; Sohail, H.M.; Liu, B.; Chen, W.; Iqbal, H.M. Impacts of renewable energy atlas: Reaping the benefits of renewables and biodiversity threats. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2020, 45, 22113–22124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; Alloing, A.; Baumbush, R.; Morandini, V. Significant decline of Griffon Vulture collision mortality in wind farms during 13-year of a selective turbine stopping protocol. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 38, e02203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estelles-Domingo, I.; Lopez-Lopez, P. Effects of wind farms on raptors: A systematic review of the current knowledge and the potential solutions to mitigate negative impacts. Anim. Conserv. 2024, 28, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, G. Golden Eagles in a Perilous Landscape: Predicting the Effects of Mitigation for Wind Turbine Blade-Strike Mortality; California Energy Commission Report: Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Katzner, T.E.; Nelson, D.M.; Braham, M.A.; Doyle, J.M.; Fernandez, N.B.; Duerr, A.E.; Bloom, P.H.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Miller, T.A.; Culver, R.C.E.; et al. Golden eagle fatalities and the continental-scale consequences of local wind-energy generation. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzner, T.E.; Brandes, D.; Miller, T.; Lanzone, M.; Maisonneuve, C.; Tremblay, J.A.; Mulvihill, R.; Merovich, G.T., Jr. Topography drives migratory flight altitude of golden eagles: Implications for on-shore wind energy development. J. Appl. Ecol. 2012, 49, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, R.F. A unifying framework for the underlying mechanisms of avian avoidance of wind turbines. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 190, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beston, J.A.; Diffendorfer, J.E.; Loss, S.R.; Johnson, D.H. Prioritizing avian species for their risk of population-level consequences from wind energy development. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janss, G.F.E. Avian mortality from power lines: A morphological approach of a species-specific mortality. Biol. Conserv. 2000, 95, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, R. Adverse impacts of wind power generation on collision behaviour of birds and anti-predator behaviour of squirrels. J. Nat. Conserv. 2008, 16, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, R.C. Structure of the VORTEX simulation model for population viability analysis. Ecol. Bull. 2000, 48, 191–203. [Google Scholar]

- Madders, M.; Whitfield, D.P. Upland raptors and the assessment of wind farm impacts. Ibis 2006, 148, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellebaum, J.; Korner-Nievergelt, F.; Dürr, T.; Mammen, U. Wind turbine fatalities approach a level of concern in a raptor population. J. Nat. Conserv. 2013, 21, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Moral, J.C.; y Molina, B. El Alimoche Común en España, Población Reproductora en 2018 y Método de Censo; SEO/BirdLife: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/portal/areas-tematicas/biodiversidad-y-vegetacion/fauna-amenazada/lucha-contra-el-veneno (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Lucha Contra el Veneno—Portal Ambiental de Andalucia. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/ (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Sánchez-Zapata, J.A.; Clavero, M.; Carrete, M.; DeVault, T.L.; Hermoso, V.; Losada, M.A.; Polo, M.J.; Sánchez-Navarro, S.; García, P.; Botella, F.; et al. Effects of renewable energy production and infrastructure on wildlife. In Current Trends in Wildlife Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 97–123. [Google Scholar]

- Wilbur, S.R.; Carrier, W.D.; Borneman, J.C. Supplemental feeding program for California Condors. J. Wildl. Manag. 1974, 38, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, I.; Marquiss, M. Effect of additional food on laying dates and clutch sizes of Sparrowhawks. Ornis Scand. 1981, 12, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrasse, J.F. The effects of artificial feeding on Griffon, Bearded and Egyptian Vultures in the Pyrenees. In Conservation Studies on Raptors; Newton, I., Chancellor, R.D., Eds.; ICBP Technical Publication: Cambridge, UK, 1985; Volume 5, pp. 429–430. [Google Scholar]

- Wiehn, J.; Korpimaki, E. Food limitation on brood size: Experimental evidence in the Eurasian kestrel. Ecology 1997, 78, 2043–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, L.M.; Margalida, A.; Sánchez, R.; Oria, J. Supplementary feeding as an effective tool for improving breeding success in the Spanish imperial eagles (Aquila adalberti). Biol. Conserv. 2006, 129, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalida, A. Supplementary feeding during the chick-rearing period is ineffective in increasing the breeding success in the bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus). Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2010, 56, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; Morandini, V.; Baguena, G.; Newton, I. Reintroducing endangered raptors: A case study of supplementary feeding and removal of nestlings from wild populations. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 1360–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Blanco, G.; DeVault, T.L.; Markandya, A.; Virani, M.; Brandt, J.; Donázar, J.A. Supplementary feeding and endangered avian scavengers: Benefits, caveats, and controversies. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrete, M.; Donázar, J.A.; Margalida, A. Density-dependent productivity depression in Pyrenean bearded vultures: Implications for conservation. Ecol. Appl. 2006, 16, 1674–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oro, D.; Margalida, A.; Carrete, M.; Heredia, R.; Donazar, J.A. Testing the goodness of supplementary feeding to enhance population viability in an endangered vulture. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-López, P.; García-Ripollés, C.; Urios, V. Food predictability determines space use of endangered vultures: Implications for management of supplementary feeding. Ecol. Appl. 2014, 24, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerecedo-Iglesias, C.; Pretus, J.L.; Hernández-Matías, A.; Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Real, J. Key Factors behind the Dynamic Stability of Pairs of Egyptian Vultures in Continental Spain. Animals 2023, 13, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandini, V.; Ferrer, M. How to plan reintroductions of long-lived birds. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, P.; Ferrer, M.; Madero, A.; Casado, E.; Mcgrady, M. Solving man-induced large-scale conservation problems: The Spanish imperial eagle and power lines. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clevenger, A.P.; Chruszcz, B.; Gunson, K.E. Spatial patterns and factors influencing small vertebrate fauna road-kill aggregations. Biol. Conserv. 2003, 109, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; Morandini, V.; Baumbush, R.; Muriel, R.; De Lucas, M.; Calabuig, C. Efficacy of different types of “bird flight diverter” in reducing bird mortality due to collision with transmission power lines. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 23, e01130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://energelia.com/ (accessed on 1 April 2024).

| Time Period | Fecundity (SD) | Mortality by Wind Turbines (SD) | Poison-Related Mortality (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Period 2004–2008 | 0.633 (0.074) | 0.80 (1.095) | 0.019 (0.02) |

| Period 2009–2022 | 0.947 (0.460) | 0.50 (0.650) | 0.009 (0.09) |

| Total 2004–2022 | 0.864 (0.418) | 0.57 (0.768) | 0.002 (0.02) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferrer, M.; García-Macía, J.; Sánchez, M.; Morandini, V. How Accurate Are Population Predictions? Wind Farms and Egyptian Vultures as a Case Study. Biology 2025, 14, 1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121743

Ferrer M, García-Macía J, Sánchez M, Morandini V. How Accurate Are Population Predictions? Wind Farms and Egyptian Vultures as a Case Study. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121743

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerrer, Miguel, Jorge García-Macía, Mar Sánchez, and Virginia Morandini. 2025. "How Accurate Are Population Predictions? Wind Farms and Egyptian Vultures as a Case Study" Biology 14, no. 12: 1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121743

APA StyleFerrer, M., García-Macía, J., Sánchez, M., & Morandini, V. (2025). How Accurate Are Population Predictions? Wind Farms and Egyptian Vultures as a Case Study. Biology, 14(12), 1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121743