Effects of Caulerpa lentillifera on Growth Performance, Antioxidant Capacity and Intestinal Microbiota of Litopenaeus vannamei

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Diets

2.2. Experimental Animals and Aquaculture Management

2.3. Sample Collection and Processing

2.4. Growth Performance and Feed Utilization

2.5. Nutritional Composition of the Whole Shrimp

2.6. Enzyme Activity Assay

2.7. RNA Extraction and qPCR Assay

2.8. Intestinal Microbial Community Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Growth Performance and Nutrient Composition

3.2. Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes in Hepatopancreas

3.3. Relative Expression Levels of Antioxidant Genes in Hepatopancreas

3.4. Relative Expression Levels of Protein Synthesis Genes in Hepatopancreas

3.5. Pearson Correlation-Based Data Analysis

3.6. Alterations in Intestinal Microbiota

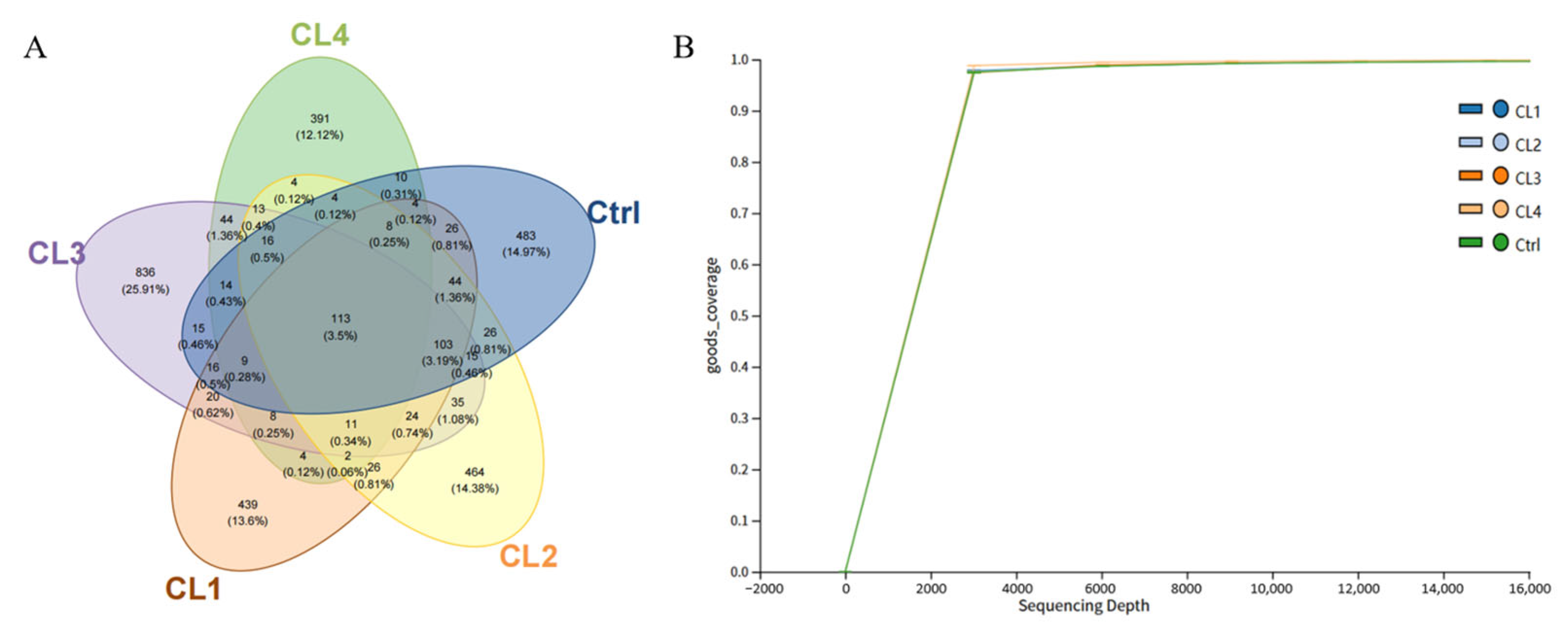

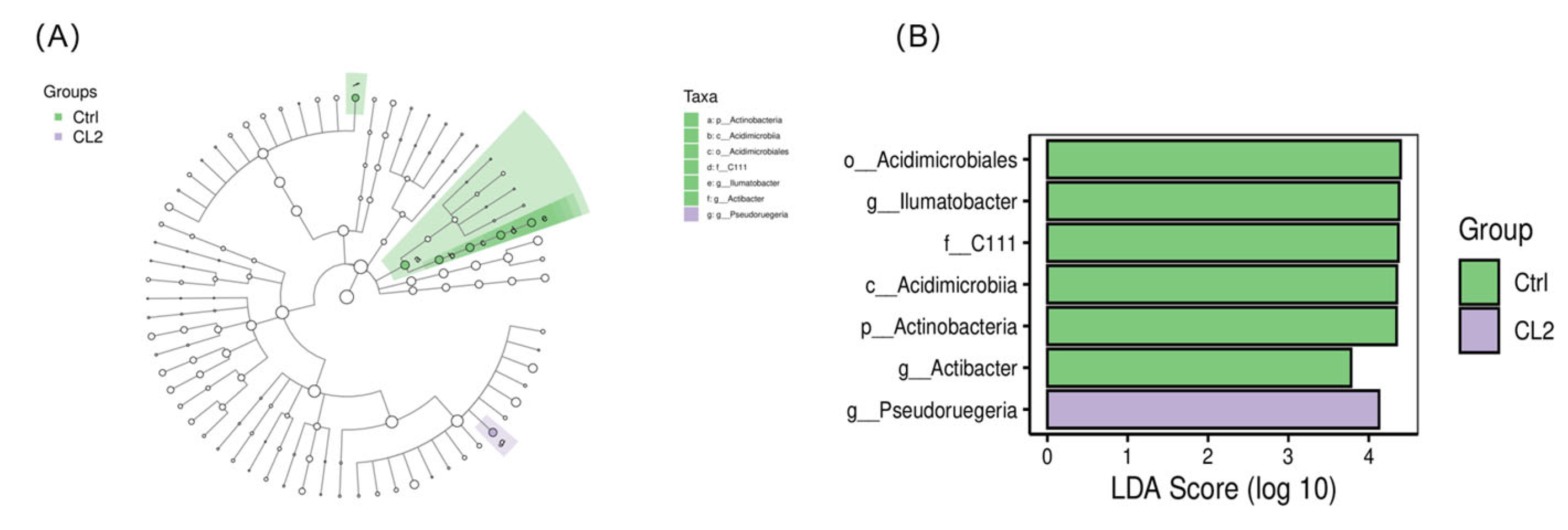

3.6.1. Microbial Diversity and Composition Changes

3.6.2. Intestinal Microbiota Phenotypes Changes

3.6.3. Prediction of Functional Abundance of the Intestinal Microbiota

3.7. The Relationship Between Intestinal Microbiota and Antioxidant Gene Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pradeepkiran, J.A. Aquaculture Role in Global Food Security with Nutritional Value: A Review. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2019, 3, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaya, E.; Davis, D.A.; Rouse, D.B. Alternative Diets for the Pacific White Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquaculture 2007, 262, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, H.; Liang, H.; Duan, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, C.; Huang, Z. Effects of Lysolecithin on Growth Performance, Antioxidant Capacity, and Lipid Metabolism of Litopenaeus vannamei. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Wang, X.; Chen, K.; Xu, C.; Qin, J.G.; Chen, L. Physiological Change and Nutritional Requirement of Pacific White Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei at Low Salinity. Rev. Aquac. 2017, 9, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics—Yearbook 2022; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025; ISBN 978-92-5-139620-9. [Google Scholar]

- Holmström, K.; Gräslund, S.; Wahlström, A.; Poungshompoo, S.; Bengtsson, B.-E.; Kautsky, N. Antibiotic Use in Shrimp Farming and Implications for Environmental Impacts and Human Health. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2003, 38, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encarnação, P. 5-Functional Feed Additives in Aquaculture Feeds. In Aquafeed Formulation; Nates, S.F., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 217–237. ISBN 978-0-12-800873-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Shi, X.; Wu, Z.; Wu, W.; Zhao, Q.; Li, E. Macroalgae Improve the Growth and Physiological Health of White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquac. Nutr. 2023, 2023, 8829291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerrifi, S.E.A.; El Khalloufi, F.; Oudra, B.; Vasconcelos, V. Seaweed Bioactive Compounds against Pathogens and Microalgae: Potential Uses on Pharmacology and Harmful Algae Bloom Control. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, W.; Wang, W.; Tian, W.; Zhang, X. Antioxidant Activity of Astragalus Polysaccharides and Antitumour Activity of the Polysaccharides and siRNA. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 82, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Gu, X.; Zhou, N.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Zhao, M. Physicochemical Characterization and Bile Acid-Binding Capacity of Water-Extract Polysaccharides Fractionated by Stepwise Ethanol Precipitation from Caulerpa lentillifera. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 150, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syakilla, N.; George, R.; Chye, F.Y.; Pindi, W.; Mantihal, S.; Wahab, N.A.; Fadzwi, F.M.; Gu, P.H.; Matanjun, P. A Review on Nutrients, Phytochemicals, and Health Benefits of Green Seaweed, Caulerpa lentillifera. Foods 2022, 11, 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinorasing, T.; Chirasuwan, N.; Bunnag, B.; Chaiklahan, R. Lipid Extracts from Caulerpa lentillifera Waste: An Alternative Product in a Circular Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Ueng, J.-P.; Tsai, G.-J. Proximate Composition, Total Phenolic Content, and Antioxidant Activity of Seagrape (Caulerpa lentillifera). J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, C950–C958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matanjun, P.; Mohamed, S.; Muhammad, K.; Mustapha, N.M. Comparison of Cardiovascular Protective Effects of Tropical Seaweeds, Kappaphycus Alvarezii, Caulerpa lentillifera, and Sargassum Polycystum, on High-Cholesterol/High-Fat Diet in Rats. J. Med. Food 2010, 13, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairuddin, K.; Sudirman, S.; Huang, L.; Kong, Z.-L. Caulerpa lentillifera Polysaccharides-Rich Extract Reduces Oxidative Stress and Proinflammatory Cytokines Levels Associated with Male Reproductive Functions in Diabetic Mice. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ai, C.; Song, S.; Chen, X. Caulerpa lentillifera Polysaccharides Enhance the Immunostimulatory Activity in Immunosuppressed Mice in Correlation with Modulating Gut Microbiota. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 4315–4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.-Y.; Yang, H.-Y.; Yang, S.-C.; Chen, Y.-L.; Watanabe, Y.; Chen, J.-R. Caulerpa lentillifera Improves Ethanol-Induced Liver Injury and Modulates the Gut Microbiota in Rats. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, E.T.; de Lira, D.P.; de Queiroz, A.C.; da Silva, D.J.C.; de Aquino, A.B.; Mella, E.A.C.; Lorenzo, V.P.; de Miranda, G.E.C.; de Araújo-Júnior, J.X.; Chaves, M.C.d.O.; et al. The Antinociceptive and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Caulerpin, a Bisindole Alkaloid Isolated from Seaweeds of the Genus Caulerpa. Mar. Drugs 2009, 7, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Li, Q.; Yang, C.; Peng, M.; Chen, X.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Y.; Feng, P.; Zeng, D.; Wang, F.; et al. Enhancing Shrimp Growth and Immunity with Green Algal Caulerpa lentillifera Polysaccharides through Gut Microbiota Regulation. Algal Res. 2024, 82, 103627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xie, X.; Fu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Xie, X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Caulerpa lentillifera Extract Alleviates the Chronic Diquat-Induced Liver Oxidative Damage in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) in Association with Nrf2 and AMPK/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 297, 110276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putra, D.F.; Rahmawati, M.; Abidin, M.Z.; Ramlan, R. Dietary Administration of Sea Grape Powder (Caulerpa lentillifera) Effects on Growth and Survival Rate of Black Tiger Shrimp (Penaeus monodon). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 348, 012100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, D.F.; Abbas, M.A.; Solin, N.; Othman, N. Effects of Dietary Caulerpa lentillifera Supplementation on Growth Performance and Survival Rate of Milk Fish, Chanos Chanos. Elkawnie: J. Islam. Sci. Technol. 2022, 7, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, Y.; Xu, R.; Tian, J.; Li, T.; Chen, S. Comparative Analysis of the Nutrient Composition of Caulerpa lentillifera from Various Cultivation Sites. Foods 2025, 14, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, F.J.; Ensminger, L.G. The Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1977, 54, 171–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyadi, A.; Djunaidah, I.S.; Rahardjo, S.; Batubara, A.S. The Combination of Lactobacillus Sp. and Turmeric Flour (Curcuma Longa) in Feed on Growth, Feed Conversion and Survival Ratio of Litopenaeus vannamei Boone, 1931. Depik J. 2022, 11, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, P. Effect of Spirulina Meal Supplementation on Growth Performance and Feed Utilization in Fish and Shrimp: A Meta-Analysis. Aquac. Nutr. 2022, 2022, 8517733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyatharshni, A.; Cheryl, A. Effect of Dietary Seaweed Supplementation on Growth, Feed Utilization, Digestibility Co-Efficient, Digestive Enzyme Activity and Challenge Study against Aeromonas Hydrophila of Nile Tilapia Oreochromis Niloticus. Indian J. Anim. Res. 2024, 58, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergün, S.; Soyutürk, M.; Güroy, B.; Güroy, D.; Merrifield, D. Influence of Ulva Meal on Growth, Feed Utilization, and Body Composition of Juvenile Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) at Two Levels of Dietary Lipid. Aquacult. Int. 2009, 17, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simtoe, A.P.; Luvanga, S.A.; Lugendo, B.R. Partial Replacement of Fishmeal with Chaetomorpha Algae Improves Feed Utilization, Survival, Biochemical Composition, and Fatty Acids Profile of Farmed Shrimp Penaeus monodon Post Larvae. Aquacult. Int. 2023, 31, 1375–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleakley, S.; Hayes, M. Algal Proteins: Extraction, Application, and Challenges Concerning Production. Foods 2017, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbary, P.; Ajdari, A.; Ajang, B. Growth, Survival, Nutritional Value and Phytochemical, and Antioxidant State of Litopenaeus vannamei Shrimp Fed with Premix Extract of Brown Sargassum ilicifolium, Nizimuddinia zanardini, Cystoseira indica, and Padina australis Macroalgae. Aquacult. Int. 2023, 31, 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingar, D.C.; Blenis, J. Target of Rapamycin (TOR): An Integrator of Nutrient and Growth Factor Signals and Coordinator of Cell Growth and Cell Cycle Progression. Oncogene 2004, 23, 3151–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.M.; Blenis, J. Molecular Mechanisms of mTOR-Mediated Translational Control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holz, M.K.; Ballif, B.A.; Gygi, S.P.; Blenis, J. mTOR and S6K1 Mediate Assembly of the Translation Preinitiation Complex through Dynamic Protein Interchange and Ordered Phosphorylation Events. Cell 2005, 123, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Haar, E.; Lee, S.-I.; Bandhakavi, S.; Griffin, T.J.; Kim, D.-H. Insulin Signalling to mTOR Mediated by the Akt/PKB Substrate PRAS40. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, L.R.; Alton, G.R.; Richter, D.T.; Kath, J.C.; Lingardo, L.; Chapman, J.; Hwang, C.; Alessi, D.R. Characterization of PF-4708671, a Novel and Highly Specific Inhibitor of P70 Ribosomal S6 Kinase (S6K1). Biochem. J. 2010, 431, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, P.P.; Topisirovic, I. Signaling Pathways Involved in the Regulation of mRNA Translation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 38, e00070-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Zavaglia, A.; Prieto Lage, M.A.; Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Mejuto, J.C.; Simal-Gandara, J. The Potential of Seaweeds as a Source of Functional Ingredients of Prebiotic and Antioxidant Value. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Xie, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, R.; Xie, X.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; et al. Metabolomics Provides Insights into the Alleviating Effect of Dietary Caulerpa lentillifera on Diquat-Induced Oxidative Damage in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Liver. Aquaculture 2024, 584, 740630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brix da Costa, B.; Stuthmann, L.E.; Cordes, A.J.; Du, H.T.; Kunzmann, A.; Springer, K. Culturing Delicacies: Potential to Integrate the Gastropod Babylonia Areolata into Pond Cultures of Caulerpa lentillifera. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 33, 101793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, F.; Chi, Y.; Xiang, J. Potential Relationship among Three Antioxidant Enzymes in Eliminating Hydrogen Peroxide in Penaeid Shrimp. Cell Stress. Chaperones 2012, 17, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xun, P.; Zhou, C.; Huang, X.; Huang, Z.; Yu, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, T.; Huang, J.; Wu, Y.; Lin, H. Effects of Dietary Sodium Acetate on Growth Performance, Fillet Quality, Plasma Biochemistry, and Immune Function of Juvenile Golden Pompano (Trachinotus ovatus). Aquac. Nutr. 2022, 2022, 9074549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candas, D.; Li, J.J. MnSOD in Oxidative Stress Response-Potential Regulation via Mitochondrial Protein Influx. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2014, 20, 1599–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.-F.; Yang, W.-J.; Xu, Q.; Chen, H.-P.; Huang, X.-S.; Qiu, L.-Y.; Liao, Z.-P.; Huang, Q.-R. DJ-1 Upregulates Anti-Oxidant Enzymes and Attenuates Hypoxia/Re-Oxygenation-Induced Oxidative Stress by Activation of the Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-like 2 Signaling Pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 4734–4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhuang, Z.; Liao, Z.; Yao, R.; Chen, M.; Wei, H.; Zhao, W.; Niu, J. Effects of Low-Fish-Meal Diet Supplemented with Coenzyme Q10 on Growth Performance, Antioxidant Capacity, Intestinal Morphology, Immunity and Hypoxic Resistance of Litopenaeus vannamei. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margis, R.; Dunand, C.; Teixeira, F.K.; Margis-Pinheiro, M. Glutathione Peroxidase Family–an Evolutionary Overview. FEBS J. 2008, 275, 3959–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid Peroxidation: Production, Metabolism, and Signaling Mechanisms of Malondialdehyde and 4-Hydroxy-2-Nonenal. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikas, D. Assessment of Lipid Peroxidation by Measuring Malondialdehyde (MDA) and Relatives in Biological Samples: Analytical and Biological Challenges. Anal. Biochem. 2017, 524, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negm, S.S.; Ismael, N.E.M.; Ahmed, A.I.; Asely, A.M.E.; Naiel, M.A.E. The Efficiency of Dietary Sargassum Aquifolium on the Performance, Innate Immune Responses, Antioxidant Activity, and Intestinal Microbiota of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Raised at High Stocking Density. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 4067–4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-C.; Zhou, S.-H.; Balasubramanian, B.; Zeng, F.-Y.; Sun, C.-B.; Pang, H.-Y. Dietary Seaweed (Enteromorpha) Polysaccharides Improves Growth Performance Involved in Regulation of Immune Responses, Intestinal Morphology and Microbial Community in Banana Shrimp Fenneropenaeus Merguiensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 104, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawzy, S.; Wang, W.; Wu, M.; Yi, G.; Huang, X. Effects of Dietary Different Canthaxanthin Levels on Growth Performance, Antioxidant Capacity, Biochemical and Immune-Physiological Parameters of White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquaculture 2022, 556, 738276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, K.; Wakabayashi, N.; Katoh, Y.; Ishii, T.; Igarashi, K.; Engel, J.D.; Yamamoto, M. Keap1 Represses Nuclear Activation of Antioxidant Responsive Elements by Nrf2 through Binding to the Amino-Terminal Neh2 Domain. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, K.; Chiba, T.; Takahashi, S.; Ishii, T.; Igarashi, K.; Katoh, Y.; Oyake, T.; Hayashi, N.; Satoh, K.; Hatayama, I.; et al. An Nrf2/Small Maf Heterodimer Mediates the Induction of Phase II Detoxifying Enzyme Genes through Antioxidant Response Elements. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 236, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, M.G.; Gallagher, E.P. A Targeted Gene Expression Platform Allows for Rapid Analysis of Chemical-Induced Antioxidant mRNA Expression in Zebrafish Larvae. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kensler, T.W.; Wakabayashi, N.; Biswal, S. Cell Survival Responses to Environmental Stresses Via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE Pathway. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 47, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. Role of Nrf2 in Oxidative Stress and Toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Guan, H.; Huang, Y.; Luo, J.; Jian, J.; Cai, S.; Yang, S. Involvement of Nrf2 in the Immune Regulation of Litopenaeus vannamei against Vibrio Harveyi Infection. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2023, 133, 108547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, B.; Yang, S.; Jian, J. Silencing of Nrf2 in Litopenaeus vannamei, Decreased the Antioxidant Capacity, and Increased Apoptosis and Autophagy. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 122, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-Y.; Liu, W.-J.; Wang, H.-C.; Lee, D.-Y.; Leu, J.-H.; Wang, H.-C.; Tsai, M.-H.; Kang, S.-T.; Chen, I.-T.; Kou, G.-H.; et al. Penaeus Monodon Thioredoxin Restores the DNA Binding Activity of Oxidized White Spot Syndrome Virus IE1. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2012, 17, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Han, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, T. Bisdemethoxycurcumin Protects Small Intestine from Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction via Activating Mitochondrial Antioxidant Systems and Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Broiler Chickens. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2021, 2021, 9927864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Zhong, G.; Nan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, M.; Li, H. Effects of Nitrite Stress on the Antioxidant, Immunity, Energy Metabolism, and Microbial Community Status in the Intestine of Litopenaeus vannamei. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liao, M.; Lin, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, G.; Ni, Z.; Sun, C. Isobaric Tags for Relative and Absolute Quantitation-Based Proteomics Analysis Provides a New Perspective into Unsynchronized Growth in Kuruma Shrimp (Marsupenaeus japonicus). Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 761103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Li, B.; Hong, Q.; Yan, Z.; Yang, X.; Lu, K.; Chen, G.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y. A Glutathione Peroxidase Gene from Litopenaeus vannamei Is Involved in Oxidative Stress Responses and Pathogen Infection Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ren, Q. A Newly Identified Hippo Homologue from the Oriental River Prawn Macrobrachium Nipponense Is Involved in the Antimicrobial Immune Response. Vet. Res. 2021, 52, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shull, S.; Heintz, N.H.; Periasamy, M.; Manohar, M.; Janssen, Y.M.; Marsh, J.P.; Mossman, B.T. Differential Regulation of Antioxidant Enzymes in Response to Oxidants. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 24398–24403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.X.; Huang, L.K.; Zhang, X.Q.; Li, Z.; Peng, Y. Effects of Heat Acclimation on Photosynthesis, Antioxidant Enzyme Activities, and Gene Expression in Orchardgrass under Heat Stress. Molecules 2014, 19, 13564–13576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.S.; Magnenat, J.L.; Bronson, R.T.; Cao, J.; Gargano, M.; Sugawara, M.; Funk, C.D. Mice Deficient in Cellular Glutathione Peroxidase Develop Normally and Show No Increased Sensitivity to Hyperoxia*. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 16644–16651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, M.; Qin, J.G.; Chen, L. Gut Microbiota and Its Modulation for Healthy Farming of Pacific White Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2018, 26, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.V.; Midtvedt, T.; Gordon, J.I. How Host-Microbial Interactions Shape the Nutrient Environment of the Mammalian Intestine. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2002, 22, 283–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastuti, Y.P.; Siregar, A.; Fatma, Y.S.; Supriyono, E. Application of a Nitrifying Bacterium Pseudomonas Sp. HIB_D to Reduce Nitrogen Waste in the Litopenaeus vannamei Cultivation Environment. Aquacult. Int. 2023, 31, 3257–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Guo, X.; Gooneratne, R.; Lai, R.; Zeng, C.; Zhan, F.; Wang, W. The Gut Microbiome and Degradation Enzyme Activity of Wild Freshwater Fishes Influenced by Their Trophic Levels. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Song, W.; Tan, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Shi, L.; Zhang, S. The Effects of Dietary Protein Level on the Growth Performance, Body Composition, Intestinal Digestion and Microbiota of Litopenaeus vannamei Fed Chlorella Sorokiniana as the Main Protein Source. Animals 2023, 13, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, S.; Nie, Q.; He, H.; Tan, H.; Geng, F.; Ji, H.; Hu, J.; Nie, S. Gut Firmicutes: Relationship with Dietary Fiber and Role in Host Homeostasis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 12073–12088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley, R.E.; Bäckhed, F.; Turnbaugh, P.; Lozupone, C.A.; Knight, R.D.; Gordon, J.I. Obesity Alters Gut Microbial Ecology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11070–11075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, S.; Berlec, A.; Štrukelj, B. The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semova, I.; Carten, J.D.; Stombaugh, J.; Mackey, L.C.; Knight, R.; Farber, S.A.; Rawls, J.F. Microbiota Regulate Intestinal Absorption and Metabolism of Fatty Acids in the Zebrafish. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 12, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Xie, S.; Zhuang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Tian, L.; Niu, J. Effects of Yeast and Yeast Extract on Growth Performance, Antioxidant Ability and Intestinal Microbiota of Juvenile Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquaculture 2021, 530, 735941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Mahowald, M.A.; Magrini, V.; Mardis, E.R.; Gordon, J.I. An Obesity-Associated Gut Microbiome with Increased Capacity for Energy Harvest. Nature 2006, 444, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; He, S.; Tan, B.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Y.; Yang, Q. Effect of Rice Protein Meal Replacement of Fish Meal on Growth, Anti-Oxidation Capacity, and Non-Specific Immunity for Juvenile Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Animals 2022, 12, 3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Xing, Y.; Zeng, S.; Dan, X.; Mo, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. Integration of Metagenomic and Metabolomic Insights into the Effects of Microcystin-LR on Intestinal Microbiota of Litopenaeus vannamei. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 994188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Lim, Y.; Joung, Y.; Cho, J.-C.; Kogure, K. Rubritalea Profundi Sp. Nov., Isolated from Deep-Seawater and Emended Description of the Genus Rubritalea in the Phylum Verrucomicrobia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 1384–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.; Matsuo, Y.; Matsuda, S.; Adachi, K.; Kasai, H.; Yokota, A. Rubritalea Sabuli Sp. Nov., a Carotenoid- and Squalene-Producing Member of the Family Verrucomicrobiaceae, Isolated from Marine Sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 992–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, H.; Katsuta, A.; Sekiguchi, H.; Matsuda, S.; Adachi, K.; Shindo, K.; Yoon, J.; Yokota, A.; Shizuri, Y. Rubritalea squalenifaciens Sp. Nov., a Squalene-Producing Marine Bacterium Belonging to Subdivision 1 of the Phylum ‘Verrucomicrobia’. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 1630–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, L.; Dai, T.; Tao, X.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Q. Influence of Light/Dark Cycles on Body Color, Hepatopancreas Metabolism, and Intestinal Microbiota Homeostasis in Litopenaeus vannamei. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 750384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.-T.; Kim, B.-H.; Oh, T.-K.; Yoon, J.-H. Pseudoruegeria Lutimaris Sp. Nov., Isolated from a Tidal Flat Sediment, and Emended Description of the Genus Pseudoruegeria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 1177–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.-L.; Lim, S.-Y.; Keat Wei, L. Species Richness and Diversity of Gut Microbiota May Reduce AHPND in the Whiteleg Shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. ASMScJ 2024, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Guo, H.; Liu, Z.; Chen, C.; Wang, K.; Huang, X.; Chen, W.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, M.; Zhang, D. Contrasting Patterns of Bacterial Communities in the Rearing Water and Gut of Penaeus vannamei in Response to Exogenous Glucose Addition. Mar. Life Sci. Technol. 2022, 4, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-H.; Lee, E.; Ko, S.-R.; Jin, S.; Song, Y.; Ahn, C.-Y.; Oh, H.-M.; Cho, B.-K.; Cho, S. Elucidation of the Biosynthetic Pathway of Vitamin B Groups and Potential Secondary Metabolite Gene Clusters Via Genome Analysis of a Marine Bacterium Pseudoruegeria Sp. M32A2M. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Cho, S.-H.; Ko, S.-R.; Jeong, Y.; Lee, E.; Jin, S.; Jeong, B.-S.; Oh, B.-H.; Oh, H.-M.; Ahn, C.-Y.; et al. Elucidation of the Algicidal Mechanism of the Marine Bacterium Pseudoruegeria Sp. M32A2M Against the Harmful Alga Alexandrium Catenella Based on Time-Course Transcriptome Analysis. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 728890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Jia, R.; Sun, T.; Wang, W.; Wang, C.; Lu, X. Insights into the Spatio-Temporal Composition, Diversity and Function of Bacterial Communities in Seawater from a Typical Laver Farm. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1056199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Cheng, J.; Chen, X.; Farag, M.A.; Cai, X.; Wang, S. Antioxidant Peptides from Lateolabrax Japonicus to Protect against Oxidative Stress Injury in Drosophila Melanogaster via Biochemical and Gut Microbiota Interaction Assays. Food Sci. Human. Wellness 2025, 14, 9250154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, R.; Wan, F.; Chen, L.; Liu, L.; Yi, B.; Zhang, H. Olive Fruit Extracts Supplement Improve Antioxidant Capacity via Altering Colonic Microbiota Composition in Mice. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 645099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Gu, Y.; Dai, X. Protective Effect of Bilberry Anthocyanin Extracts on Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Intestinal Damage in Drosophila Melanogaster. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, F.; Liu, L.; Zhang, T. Evidence of Carbon Fixation Pathway in a Bacterium from Candidate Phylum SBR1093 Revealed with Genomic Analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ingredients a | Ctrl | CL1 | CL2 | CL3 | CL4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. lentillifera b | 0.00 | 2.50 | 5.00 | 7.50 | 10.00 |

| Fish meal | 25.00 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 25.00 |

| Soybean meal | 18.00 | 18.00 | 18.00 | 18.00 | 18.00 |

| Peanut meal | 16.40 | 16.40 | 16.40 | 16.40 | 16.40 |

| Wheat flour | 24.00 | 14.00 | 14.00 | 14.00 | 14.00 |

| Bentonite | 0.00 | 7.50 | 5.00 | 2.50 | 0.00 |

| Beer yeast | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Krill meal | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Soy lecithin | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Fish oil | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Soybean oil | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Choline chloride (50%) | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Dicalcium phosphate | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Multi-minerals c | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Multi-vitamins d | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Vc phosphate | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Sum | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Nutrient levels (dry weight) | |||||

| Moisture | 7.34 | 8.25 | 8.51 | 7.45 | 7.90 |

| Ash | 13.36 | 15.72 | 15.70 | 14.43 | 14.07 |

| Crude protein | 45.27 | 44.47 | 44.69 | 45.77 | 46.36 |

| Crude lipid | 10.96 | 10.92 | 11.08 | 11.59 | 11.61 |

| Items | Ctrl | CL1 | CL2 | CL3 | CL4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBW 1 (g) | 2.53 ± 0.03 | 2.42 ± 0.08 | 2.50 ± 0.06 | 2.42 ± 0.06 | 2.51 ± 0.05 |

| FBW 2 (g) | 11.07 ± 0.27 | 9.89 ± 0.17 | 10.60 ± 0.51 | 10.80 ± 1.07 | 10.57 ± 0.43 |

| SR (%) | 99.17 ± 1.66 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 95.83 ± 3.19 | 94.17 ± 5.00 | 92.50 ± 5.00 |

| WGR (g) | 337.31 ± 7.80 | 309.72 ± 19.62 | 324.57 ± 22.64 | 344.92 ± 34.25 | 321.62 ± 18.93 |

| SGR (% d−1) | 2.73 ± 0.03 | 2.61 ± 0.09 | 2.67 ± 0.10 | 2.76 ± 0.14 | 2.66 ± 0.08 |

| FCR | 1.19 ± 0.04 | 1.19 ± 0.03 | 1.11 ± 0.07 | 1.11 ± 0.06 | 1.15 ± 0.04 |

| PER | 1.86 ± 0.06 | 1.90 ± 0.04 | 2.04 ± 0.13 | 1.96 ± 0.11 | 1.87 ± 0.06 |

| Items | Ctrl | CL1 | CL2 | CL3 | CL4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 76.63 ± 0.49 | 76.11 ± 0.19 | 76.37 ± 0.83 | 76.03 ± 0.43 | 76.11 ± 0.50 |

| Crude protein | 75.70 ± 0.26 c | 78.55 ± 0.16 a | 78.32 ± 0.15 ab | 77.99 ± 0.21 b | 77.20 ± 1.03 abc |

| Crude lipid | 4.77 ± 0.41 | 4.77 ± 0.56 | 4.83 ± 0.74 | 4.37 ± 0.69 | 3.97 ± 0.67 |

| Ash | 12.52 ± 0.50 | 12.42 ± 0.64 | 12.57 ± 0.81 | 12.83 ± 0.57 | 13.36 ± 0.74 |

| Items | Ctrl | CL1 | CL2 | CL3 | CL4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-AOC | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 |

| T-SOD | 7.58 ± 1.24 c | 14.60 ± 1.15 ab | 12.32 ± 0.97 b | 15.50 ± 0.60 a | 13.88 ± 1.68 ab |

| CAT | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.01 |

| GPx | 185.82 ± 12.02 d | 353.47 ± 9.24 a | 328.83 ± 3.52 b | 234.04 ± 5.92 c | 132.38 ± 3.86 e |

| MDA | 1.79 ± 0.42 a | 1.05 ± 0.10 a | 0.43 ± 0.03 b | 1.13 ± 0.31 ab | 1.18 ± 0.21 a |

| POD | 1.52 ± 0.20 b | 1.45 ± 0.32 b | 1.86 ± 0.13 ab | 2.12 ± 0.25 a | 2.26 ± 0.27 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, H.; Tian, J.; Wang, Y.; Duan, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, C.; Huang, Z. Effects of Caulerpa lentillifera on Growth Performance, Antioxidant Capacity and Intestinal Microbiota of Litopenaeus vannamei. Biology 2025, 14, 1738. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121738

Liang H, Tian J, Wang Y, Duan Y, Wang J, Zhou C, Huang Z. Effects of Caulerpa lentillifera on Growth Performance, Antioxidant Capacity and Intestinal Microbiota of Litopenaeus vannamei. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1738. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121738

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Hong, Jialin Tian, Yun Wang, Yafei Duan, Jun Wang, Chuanpeng Zhou, and Zhong Huang. 2025. "Effects of Caulerpa lentillifera on Growth Performance, Antioxidant Capacity and Intestinal Microbiota of Litopenaeus vannamei" Biology 14, no. 12: 1738. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121738

APA StyleLiang, H., Tian, J., Wang, Y., Duan, Y., Wang, J., Zhou, C., & Huang, Z. (2025). Effects of Caulerpa lentillifera on Growth Performance, Antioxidant Capacity and Intestinal Microbiota of Litopenaeus vannamei. Biology, 14(12), 1738. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121738