AI-Powered Structural and Co-Expression Analysis of Potato (Solanum tuberosum) StABCG25 Transporters Under Drought: A Combined AlphaFold, WGCNA, and MD Approach

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification and Characterization of ABCG25 Homologs in Potato

2.2. Promoter Analysis for ABA-Responsive Elements

2.3. RNA-Seq Data Analysis

2.3.1. Data Pre-Processing and Quality Control

2.3.2. Alignment to the Reference Genome

2.3.3. Gene Expression Quantification

2.3.4. Z-Score Transformation for Heatmap Visualization

2.4. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

2.4.1. Data Input and Pre-Processing

2.4.2. Network Construction and Module Detection

2.4.3. Module-Trait Association and Hub Gene Identification

2.4.4. Network Visualization

2.4.5. Differential Alternative Splicing (AS) Analysis

2.4.6. Ontology Analysis

2.5. Deep Learning-Based Protein Structure Prediction (AlphaFold2–ColabFold)

2.6. Molecular Docking Processes

2.7. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| antechamber -i ligand_H.mol2 -fi mol2 -o ligand_charge.mol2 -fo mol2 -at gaff -dr no -c resp -nc 0 |

| saveamberparm complex complex_su.prmtop complex_su.crd |

2.8. MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA Free Energy Calculations

3. Results

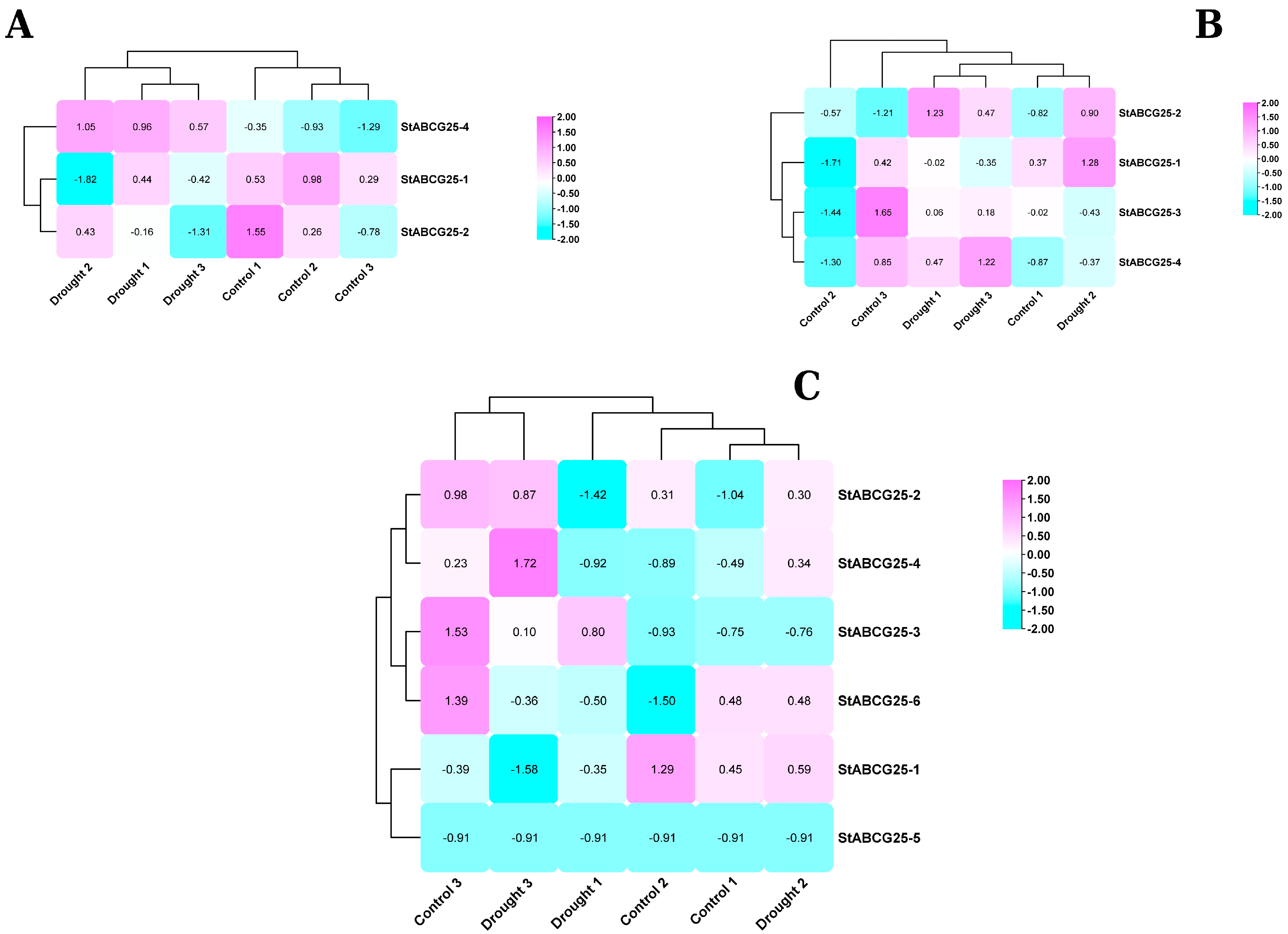

3.1. Contrasting Drought Responses of the StABCG25 Gene Family in Tolerant and Susceptible Potato Cultivars

3.2. The Effect of Drought Stress on Alternative Splicing in the Potato Transcriptome

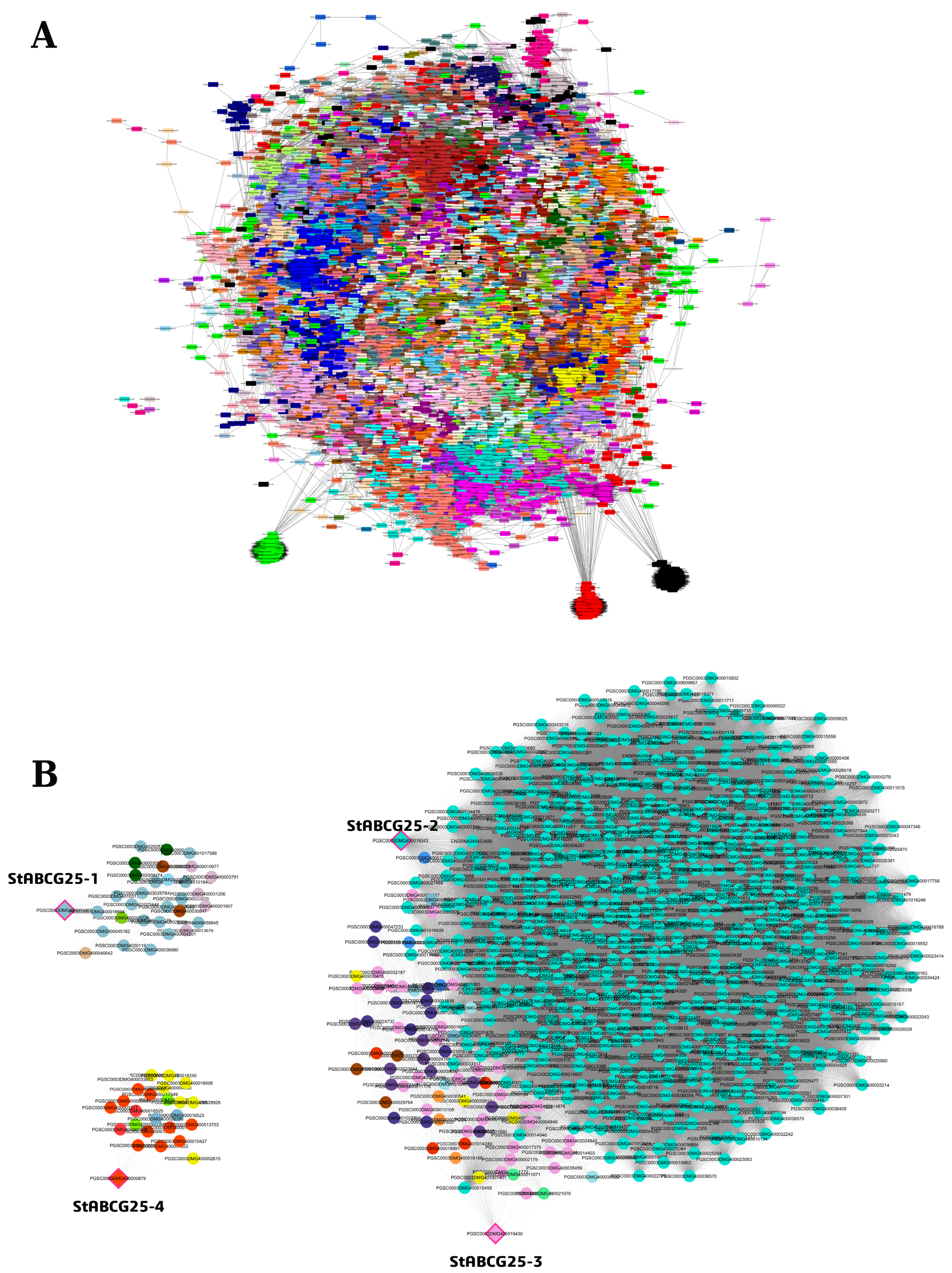

3.3. Co-Expression Network Analysis of StABCG25 Genes in Leaf Tissue

3.3.1. Network Topology and Functional Context of StABCG25-1

3.3.2. Critical Role of StABCG25-2 and StABCG25-3 in Stress and Defense Networks

3.3.3. StABCG25-4 Network: Loose Topology and Regulatory Gene Enrichment

3.3.4. Gene Ontology Enrichment and Functional Analysis in Leaf Tissue

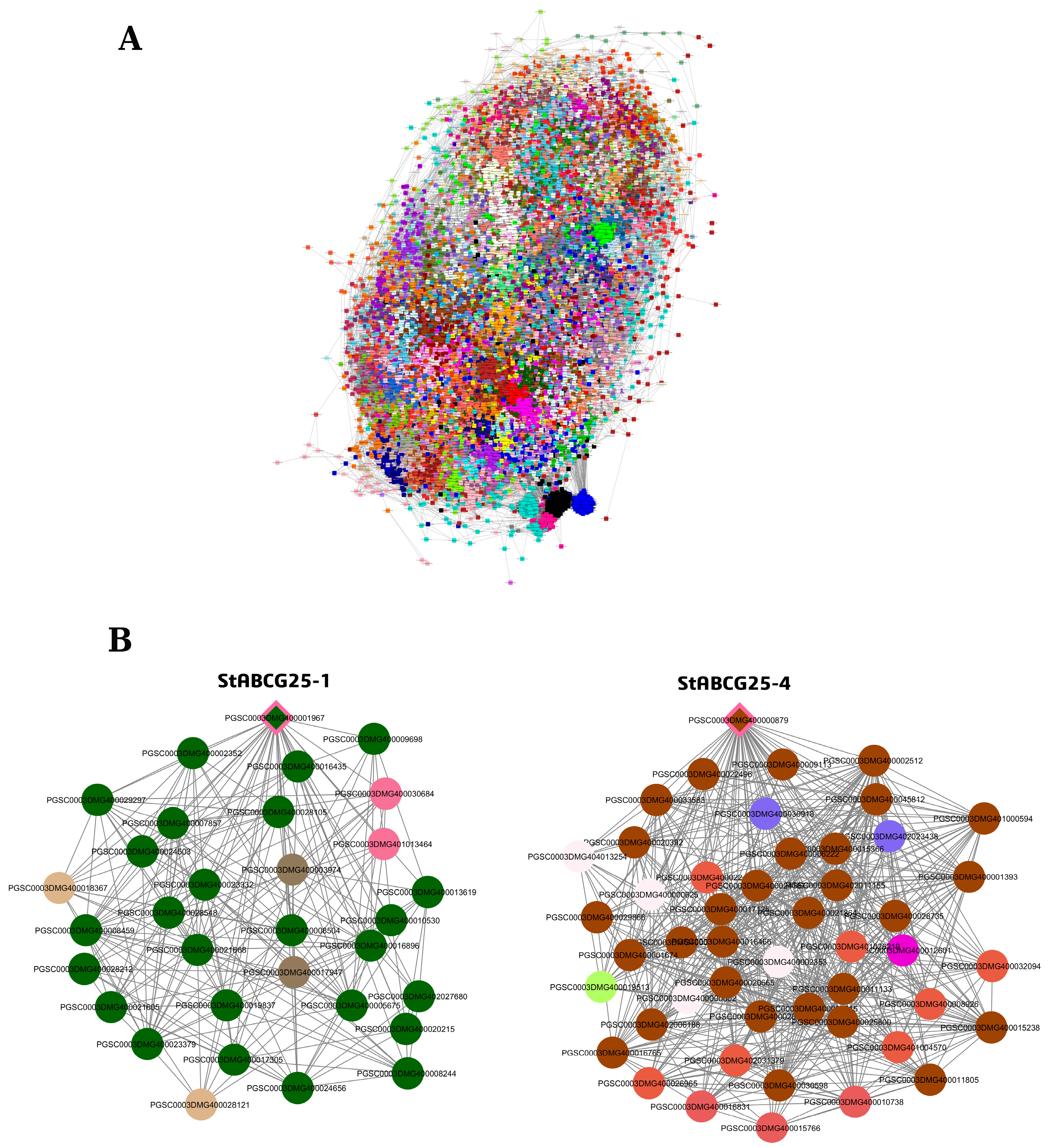

3.4. Co-Expression Network Analysis of StABCG25 Genes in Tuber Tissue

3.4.1. Network Topology and Regulatory Strategy of StABCG25-1

3.4.2. StABCG25-4 Network: Density Differences and Regulatory Mechanisms

3.4.3. Gene Ontology Enrichment and Biological Insights in Tuber Tissue

- The darkgreen module, which includes StABCG25-1, was associated with protein homodimerization activity (GO:0042803). This suggests that StABCG25-1 may function through protein–protein interactions as part of larger regulatory complexes.

- The chocolate4 module (StABCG25-4) was enriched in processes related to plastid transcription (GO:0042793) and plastids (GO:0009536) in general, pointing to a potential role for StABCG25-4 in plastid-related signaling or functions.

- Other modules, such as navajowhite4, reflected core stress and regulatory mechanisms by being enriched in terms of cold acclimation (GO:0009631), chromatin remodeling (GO:0006338), and the regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II (GO:0006357).

3.5. AlphaFold2 Modeling Quality Assessment

- pLDDT (Predicted Local Distance Difference Test): A confidence score assigned to each amino acid position on a scale from 0 to 100, reflecting the local reliability of the model. Scores above 90 indicate high confidence in the predicted region.

- PAE (Predicted Aligned Error): This metric reflects the positional uncertainty between different regions of the protein, primarily used to assess inter-domain alignment reliability. Low PAE values (<5 Å) suggest well-aligned and structurally consistent relationships between domains.

- Sequence Coverage: Represents the depth of evolutionary information (homologous sequences) included in the model. High sequence coverage implies the prediction is supported by rich sequence data and is thus considered more reliable.

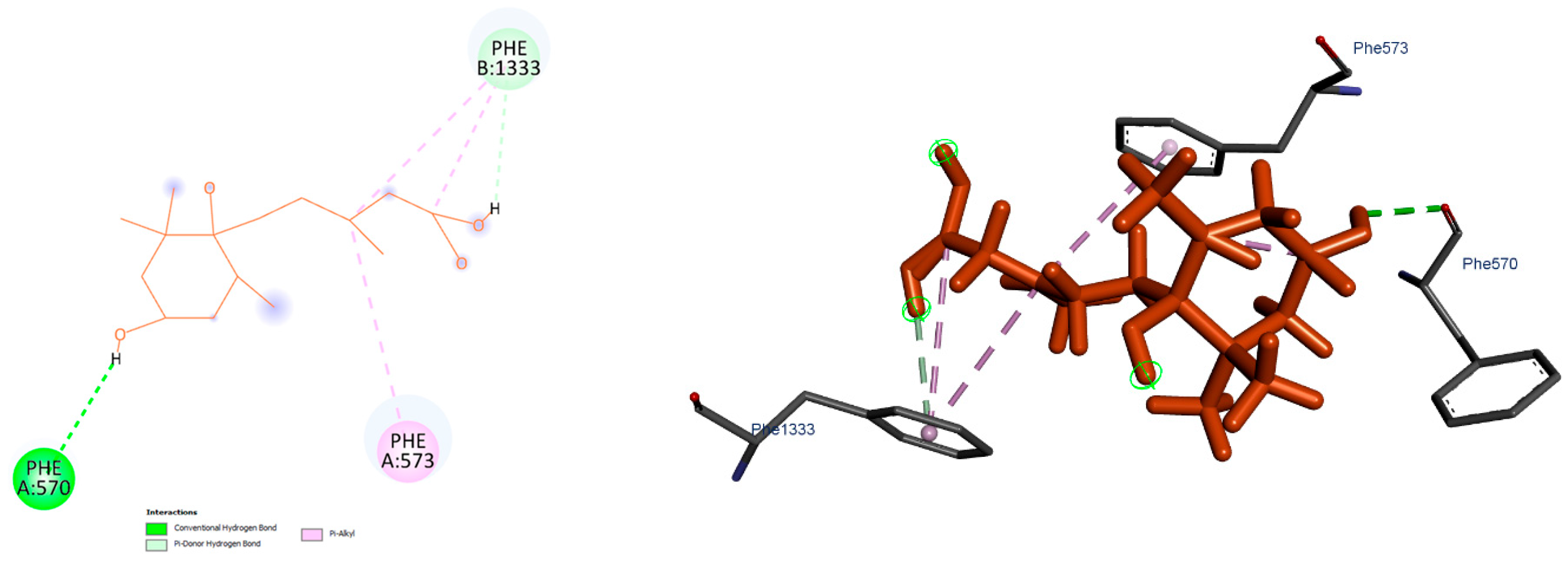

3.6. Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Analyses

3.7. RMSD Analysis

- The StABCG25-1 model displayed a continuous increase up to approximately 450 ns, eventually reaching ~7 Å by the end of the simulation, indicating a considerable structural deviation. However, the RMSD curve started to plateau after 450 ns, suggesting a transition toward a more stable conformation.

- The StABCG25-2 model showed the lowest RMSD values among all models, maintaining a stable trajectory around 3.5 Å throughout the simulation. This consistency indicates that the model remained close to its initial conformation and exhibits strong structural stability.

- The StABCG25-3 model demonstrated a marked RMSD increase during the first 400 ns, after which the curve gradually plateaued around 14 Å. This pattern suggests an initial structural adaptation phase, followed by convergence to a more stable form. It appears that the simulation time was sufficient for this model to reach a near-final conformation.

- The StABCG25-4 model exhibited a steadily increasing RMSD with moderate fluctuations, stabilizing around 7 Å toward the end of the simulation. Despite undergoing some structural rearrangements, the model overall maintained a reasonably balanced structure.

- The StABCG25-5A model showed a sharp rise in RMSD, peaking around 17 Å. This suggests a highly flexible structure with significant conformational transitions occurring throughout the simulation.

3.8. RMSF Analysis

- The StABCG25-1 model, which displayed substantial RMSD fluctuations throughout the simulation, showed RMSF values consistent with this structural flexibility. Notably, the N-terminal region (residues ~1–50) exhibited fluctuations exceeding 20 Å. Additional mobility was observed in mid-regions (~600–700) and near the C-terminus, suggesting widespread flexibility that aligns with the model’s overall structural instability.

- The StABCG25-2 model, which showed minimal deviations in the RMSD analysis, also demonstrated limited fluctuations in the RMSF profile. Across the structure, most RMSF values remained within the 5–15 Å range, indicating strong local stability. Although minor flexibility was observed in certain loop regions (~200, ~800), these fluctuations were not significant enough to compromise the model’s overall structural integrity.

- The StABCG25-3 model, which had reached a plateau in its RMSD curve after 400 ns, showed a concentrated fluctuation pattern in the RMSF analysis. Sharp peaks were observed in regions ~400–500, ~800–900, and ~1200–1300, indicating the presence of a few structurally flexible segments. The rest of the structure showed stabilized RMSF values around 3–5 Å, supporting the notion that the model had converged toward a stable conformation.

- The StABCG25-4 model, which exhibited moderate RMSDs, revealed some localized flexibility in the RMSF analysis. Mobility was mainly seen in the N-terminal segment (~1–50) and around residue ~600. Overall, the model appears to be well-balanced, with restricted flexibility confined to a few regions.

- The StABCG25-5A model showed high structural mobility in both RMSD and RMSF analyses. Multiple regions exceeded 10 Å in RMSF, with the segments between ~100–200 and ~800–1000 displaying even more pronounced fluctuations.

- The StABCG25-5B model, which had the highest RMSD values among all, confirmed this dynamic behavior through the RMSF profile. Very high fluctuation values (20–25 Å) were found in the N-terminal region (residues 1–150), around residue ~800, and in some central segments (~400–500), reflecting extensive conformational rearrangements and a lack of structural integrity, similar to what was observed for StABCG25-5A.

- The StABCG25-6 model emerged as the most stable in both RMSD and RMSF analyses. RMSF values remained within the narrow 3–7 Å range, and even the terminal regions did not exhibit significant mobility. This indicates a highly stable structure, both locally and globally, that preserved its conformational integrity throughout the simulation.

3.9. MMPBSA and MMGBSA Energy Calculations

4. Discussion

4.1. Originality of Annotation and Scope of the Study on ABCG25 Candidate Genes

4.2. Coordinated Activation of StABCG25 Genes and Drought Tolerance

4.3. Transcriptional Coordination and Redundancy Management

4.4. Dominant Role of Transcriptional Regulation and Promoter-Controlled Expression

4.5. Genomic Coordination of Transcription Factors and Epigenetic Regulators

4.6. Complexity in ABA Transport: Heterodimerization and Transporter Redundancy

4.7. Structural Predictions and Docking Analyses

4.8. Structural Specialization and Divergence from Transcriptional Regulation

4.8.1. StABCG25-6: High Structural Stability, Low Transcription

4.8.2. StABCG25-4: High Expression, Dynamic Structure, and Plastid Association

4.9. Significance of an Integrated Approach and Functional Implications

5. Conclusions

Future Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Kuromori, T.; Miyaji, T.; Yabuuchi, H.; Shimizu, H.; Sugimoto, E.; Kamiya, A.; Moriyama, Y.; Shinozaki, K. ABC Transporter AtABCG25 Is Involved in Abscisic Acid Transport and Responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 2361–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuromori, T.; Sugimoto, E.; Shinozaki, K. Intertissue Signal Transfer of Abscisic Acid from Vascular Cells to Guard Cells. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 1587–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Li, C.; Wu, J.; Zhao, M.; Chen, D.; Liu, C.; Chu, J.; Zhang, W.; Hwang, I.; Wang, M. SORTING NEXIN2 Proteins Mediate Stomatal Movement and the Response to Drought Stress by Modulating Trafficking and Protein Levels of the ABA Exporter ABCG25. Plant J. 2022, 110, 1603–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.; Huang, X.; Ma, T.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Lu, H.; Xue, H. Integrated Analysis of miRNAome and Transcriptome Identify Regulators of Elm Seed Aging. Plants 2023, 12, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merilo, E.; Jalakas, P.; Laanemets, K.; Mohammadi, O.; Hõrak, H.; Kollist, H.; Brosché, M. Abscisic Acid Transport and Homeostasis in the Context of Stomatal Regulation. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 1321–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovinich, N.; Wang, Y.; Adegboye, J.; Chanoca, A.A.; Otegui, M.S.; Durkin, P.; Grotewold, E. Arabidopsis MATE 45 Antagonizes Local Abscisic Acid Signaling to Mediate Development and Abiotic Stress Responses. Plant Direct 2018, 2, e00087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, R.; Huang, A.; Mo, R.; Zou, C.; Wei, X.; Yang, M.; Tan, H.; Huang, K.; Qin, J. SNP-Based Bulk Segregant Analysis Revealed Disease Resistance QTLs Associated with Northern Corn Leaf Blight in Maize. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1038948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, L.; Allan, A.C.; Sun, C.; Duan, Y.; Li, X.; et al. A Metabolic Perspective of Selection for Fruit Quality Related to Apple Domestication and Improvement. Genome Biol. 2023, 24, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durrant, J.D.; McCammon, J.A. Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Drug Discovery. BMC Biol. 2011, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatima, A.; Khanum, G.; Srivastava, S.K.; Bhattacharya, P.; Ali, A.; Arora, H.; Siddiqui, N.; Javed, S. Exploring Quantum Computational, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation with MMGBSA Studies of Ethyl-2-Amino-4-Methyl Thiophene-3-Carboxylate. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 10411–10429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: A Worldwide Hub of Protein Knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D506–D515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodstein, D.M.; Shu, S.; Howson, R.; Neupane, R.; Hayes, R.D.; Fazo, J.; Mitros, T.; Dirks, W.; Hellsten, U.; Putnam, N.; et al. Phytozome: A Comparative Platform for Green Plant Genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D1178–D1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Matsuura, Y.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological Systems Database as a Model of the Real World. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D672–D677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M. PlantCARE, a Database of Plant Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements and a Portal to Tools for in Silico Analysis of Promoter Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Fujita, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. ABA-Mediated Transcriptional Regulation in Response to Osmotic Stress in Plants. J. Plant Res. 2011, 124, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, H.; Urao, T.; Ito, T.; Seki, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Arabidopsis AtMYC2 (bHLH) and AtMYB2 (MYB) Function as Transcriptional Activators in Abscisic Acid Signaling. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasternack, C.; Strnad, M. Jasmonate Signaling in Plant Stress Responses and Development—Active and Inactive Compounds. New Biotechnol. 2016, 33, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reidt, W.; Wohlfarth, T.; Ellerström, M.; Czihal, A.; Tewes, A.; Ezcurra, I.; Rask, L.; Bäumlein, H. Gene Regulation during Late Embryogenesis: The RY Motif of Maturation-specific Gene Promoters Is a Direct Target of the FUS3 Gene Product. Plant J. 2000, 21, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamoto, K.; Masutomi, H.; Matsumoto, Y.; Akutsu, K.; Momiki, R.; Ishihara, K. Drought Response of Tuber Genes in Processing Potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.) in Japan. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barra, M.; Meneses, C.; Riquelme, S.; Pinto, M.; Lagüe, M.; Davidson, C.; Tai, H.H. Transcriptome Profiles of Contrasting Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Genotypes Under Water Stress. Agronomy 2019, 9, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, R.; Sugawara, H.; Shumway, M.; on behalf of the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration. The Sequence Read Archive. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, D19–D21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Galaxy Community; Afgan, E.; Nekrutenko, A.; Grüning, B.A.; Blankenberg, D.; Goecks, J.; Schatz, M.C.; Ostrovsky, A.E.; Mahmoud, A.; Lonie, A.J.; et al. The Galaxy Platform for Accessible, Reproducible and Collaborative Biomedical Analyses: 2022 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W345–W351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sena Brandine, B.; Simith, A.D. Falco: High-speed, FASTQ-only quality control for next-generation sequencing data. F1000Research 2021, 8, 1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize Analysis Results for Multiple Tools and Samples in a Single Report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3047–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An Ultra-Fast All-in-One FASTQ Preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences from High-Throughput Sequencing Reads. EMBnet. J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast Universal RNA-Seq Aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.W.; Amode, M.R.; Austine-Orimoloye, O.; Azov, A.G.; Barba, M.; Barnes, I.; Becker, A.; Bennett, R.; Berry, A.; Bhai, J.; et al. Ensembl 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D891–D899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Li, W. RSeQC: Quality Control of RNA-Seq Experiments. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2184–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An Efficient General Purpose Program for Assigning Sequence Reads to Genomic Features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; Posit PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R Package for Weighted Correlation Network Analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Kutschera, E.; Adams, J.I.; Kadash-Edmondson, K.E.; Xing, Y. rMATS-Turbo: An Efficient and Flexible Computational Tool for Alternative Splicing Analysis of Large-Scale RNA-Seq Data. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 1083–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Pan, S.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, B.; Mu, D.; Ni, P.; Zhang, G.; Yang, S.; Li, R.; Wang, J.; et al. Genome Sequence and Analysis of the Tuber Crop Potato. Nature 2011, 475, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A Universal Enrichment Tool for Interpreting Omics Data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene Ontology: Tool for the Unification of Biology. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Gene Ontology Consortium; Aleksander, S.A.; Balhoff, J.; Carbon, S.; Cherry, J.M.; Drabkin, H.J.; Ebert, D.; Feuermann, M.; Gaudet, P.; Harris, N.L.; et al. The Gene Ontology Knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 2023, 224, iyad031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Chan, H.C.S.; Hu, Z. Using PyMOL as a Platform for Computational Drug Design. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2017, 7, e1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, P.; Swails, J.; Chodera, J.D.; McGibbon, R.T.; Zhao, Y.; Beauchamp, K.A.; Wang, L.-P.; Simmonett, A.C.; Harrigan, M.P.; Stern, C.D.; et al. OpenMM 7: Rapid Development of High Performance Algorithms for Molecular Dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated Docking with Selective Receptor Flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pence, H.E.; Williams, A. ChemSpider: An Online Chemical Information Resource. J. Chem. Educ. 2010, 87, 1123–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, D.A.; Aktulga, H.M.; Belfon, K.; Cerutti, D.S.; Cisneros, G.A.; Cruzeiro, V.W.D.; Forouzesh, N.; Giese, T.J.; Götz, A.W.; Gohlke, H.; et al. AmberTools. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 6183–6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BIOVIA. Dassault Systèmes Discovery Studio Visualizer; BIOVIA: San Diego, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Case, D.A.; Aktulga, H.M.; Belfon, K.; Ben-Shalom, I.Y.; Berryman, J.T.; Brozell, S.R.; Cerutti, D.S.; Cheatham, T.E.; Cisneros, G.A.; Cruzeiro, V.W.D.; et al. AMBER 2024; University of California: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bergonzo, C.; Cheatham, T.E.I. Improved Force Field Parameters Lead to a Better Description of RNA Structure. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 3969–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayatshahi, H.S.; Henriksen, N.M.; Cheatham, T.E.I. Consensus Conformations of Dinucleoside Monophosphates Described with Well-Converged Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018, 14, 1456–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smardz, P.; Anila, M.M.; Rogowski, P.; Li, M.S.; Różycki, B.; Krupa, P. A Practical Guide to All-Atom and Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics Simulations Using Amber and Gromacs: A Case Study of Disulfide-Bond Impact on the Intrinsically Disordered Amyloid Beta. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirts, M.R.; Klein, C.; Swails, J.M.; Yin, J.; Gilson, M.K.; Mobley, D.L.; Case, D.A.; Zhong, E.D. Lessons Learned from Comparing Molecular Dynamics Engines on the SAMPL5 Dataset. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2017, 31, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp, K.; Bruns, C.; Chodera, J.; Eastman, P.; Friedrichs, M.; Ku, J.P.; Markland, T.; Pande, V.; Radmer, R.; Sherman, M.; et al. OpenMM User Guide. Available online: http://docs.openmm.org/latest/userguide/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Miller, B.R.I.; McGee, T.D., Jr.; Swails, J.M.; Homeyer, N.; Gohlke, H.; Roitberg, A.E. MMPBSA.Py: An Efficient Program for End-State Free Energy Calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3314–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollman, P.A.; Massova, I.; Reyes, C.; Kuhn, B.; Huo, S.; Chong, L.; Lee, M.; Lee, T.; Duan, Y.; Wang, W.; et al. Calculating Structures and Free Energies of Complex Molecules: Combining Molecular Mechanics and Continuum Models. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000, 33, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, W. Assessing the Performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods. 1. The Accuracy of Binding Free Energy Calculations Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011, 51, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genheden, S.; Ryde, U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods to Estimate Ligand-Binding Affinities. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2015, 10, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liang, J. Endomembrane-Biased Dimerization of ABCG16 and ABCG25 Transporters Determines Their Substrate Selectivity in ABA-Regulated Plant Growth and Stress Responses. Mol. Plant 2024, 17, 478–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, M.; He, D.; Wang, K.; Yang, P. Mutations on Ent-Kaurene Oxidase 1 Encoding Gene Attenuate Its Enzyme Activity of Catalyzing the Reaction from Ent-Kaurene to Ent-Kaurenoic Acid and Lead to Delayed Germination in Rice. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1008562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Brock, N.; Halford, N.G. Structural analyses of ABA transporters give new impetus to the study of ABA regulation. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, X.; An, N.; Zhang, M.; Ma, M.; Yang, Y.; Jing, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, P. Cryo-EM Structure and Molecular Mechanism of Abscisic Acid Transporter ABCG25. Nat. Plants 2023, 9, 1709–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, J.; Zhou, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Geng, H.; Wang, Y.; Song, Y.; Liang, J.; Yan, K. Structural Insights into AtABCG25, an Angiosperm-Specific Abscisic Acid Exporter. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 100776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercruyssen, L.; Verkest, A.; Gonzalez, N.; Heyndrickx, K.S.; Eeckhout, D.; Han, S.-K.; Jégu, T.; Archacki, R.; Van Leene, J.; Andriankaja, M.; et al. ANGUSTIFOLIA3 Binds to SWI/SNF Chromatin Remodeling Complexes to Regulate Transcription during Arabidopsis Leaf Development. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, D.-X. Epigenetic Gene Regulation by Plant Jumonji Group of Histone Demethylase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Regul. Mech. 2011, 1809, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi, L.; Kang, J.; Ko, D.; Lee, Y.; Martinoia, E. The Role of ABCG-Type ABC Transporters in Phytohormone Transport. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015, 43, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.H.; Lee, M.H.; Song, K.; Ahn, G.; Lee, J.; Hwang, I. The A/ENTH Domain-Containing Protein AtECA4 Is an Adaptor Protein Involved in Cargo Recycling from the Trans-Golgi Network/Early Endosome to the Plasma Membrane. Mol. Plant 2018, 11, 568–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.V.; Evarestov, R.A. TiS2 and ZrS2 Single- and Double-Wall Nanotubes: First-Principles Study. J. Comput. Chem. 2014, 35, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldeghi, M.; Ross, G.A.; Bodkin, M.J.; Essex, J.W.; Knapp, S.; Biggin, P.C. Large-Scale Analysis of Water Stability in Bromodomain Binding Pockets with Grand Canonical Monte Carlo. Commun. Chem. 2018, 1, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidya, A.S.; Helander, J.D.M.; Peterson, F.C.; Elzinga, D.; Dejonghe, W.; Kaundal, A.; Park, S.-Y.; Xing, Z.; Mega, R.; Takeuchi, J.; et al. Dynamic Control of Plant Water Use Using Designed ABA Receptor Agonists. Science 2019, 366, eaaw8848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkhowa, S.; Zaheen, A.; Hussain, S.Z.; Barthakur, S. Harnessing Virtual Insights: A Computational Study on the Molecular Characterization of a Drought-Inducible RNA-Binding Protein for Enhancing Drought Tolerance in Mungbean (Vigna radiata L.). ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202403028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waidyarathne, P.; Samarasinghe, S. A System of Subsystems: Hierarchical Modularity of Guard Cell ABA Signalling Network Defines Its Evolutionary Success. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1109988. [Google Scholar]

| Gene ID | Transcript ID | 1 Assigned Name | Total ABA Score 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PGSC0003DMG400001967 | PGSC0003DMT400004973 | StABCG25-1 | 11 |

| PGSC0003DMG400015343 | PGSC0003DMT400039671 | StABCG25-2 | 10 |

| PGSC0003DMG400019430 | PGSC0003DMT400050007 | StABCG25-3 | 9 |

| PGSC0003DMG400000879 | PGSC0003DMT400002293 | StABCG25-4 | 9 |

| PGSC0003DMG400000787 | PGSC0003DMT400002061 | StABCG25-5A | 9 |

| PGSC0003DMG400000787 | PGSC0003DMT400002062 | StABCG25-5B | 8 |

| PGSC0003DMG400019295 | PGSC0003DMT400049667 | StABCG25-6 | 8 |

| AS Event Type | Leaf (Cardinal) | Leaf (FB Clone) | Tuber |

|---|---|---|---|

| SE (Skipped Exon) | 10 | 57 | 80 |

| RI (Retained Intron) | 46 | 212 | 170 |

| MXE (Mutually Exclusive Exons) | 0 | 4 | 7 |

| A5SS (Alt. 5′ Splice Site) | 13 | 34 | 29 |

| A3SS (Alt. 3′ Splice Site) | 42 | 72 | 59 |

| Total | 111 | 379 | 345 |

| Model | Coverage | PAE Intra | PAE Inter | pLDDT Avg. | pLDDT Consistency | Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| StABCG25-1 | High | Yes | Yes | 85 | High | Good overall |

| StABCG25-2 | High | Yes | Yes | 80 | High | Good overall |

| StABCG25-3 | High | Yes | Yes | 78 | High | Good overall |

| StABCG25-4 | High | Yes | Partial | 82 | High | Good overall |

| StABCG25-5a | High | Yes | No | 76 | High | Good overall |

| StABCG25-5b | High | Yes | Partial | 79 | High | Good overall |

| StABCG25-6 | High | Yes | No | 77 | High | Good overall |

| Models | Docking | MMPBSA | MMGBSA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | −5.9 | −4.6483 | −15.9602 |

| Model 2 | −6.3 | −4.2699 | −26.0802 |

| Model 3 | −6.4 | 2.0634 | −16.3797 |

| Model 4 | −6.2 | 2.2088 | −24.0798 |

| Model 5a | −6.3 | −2.651 | −36.6501 |

| Model 5b | −6.6 | −4.9877 | −44.5229 |

| Model 6 | −6.2 | −6.3511 | −37.1078 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurt, B.; Kurt, F. AI-Powered Structural and Co-Expression Analysis of Potato (Solanum tuberosum) StABCG25 Transporters Under Drought: A Combined AlphaFold, WGCNA, and MD Approach. Biology 2025, 14, 1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121723

Kurt B, Kurt F. AI-Powered Structural and Co-Expression Analysis of Potato (Solanum tuberosum) StABCG25 Transporters Under Drought: A Combined AlphaFold, WGCNA, and MD Approach. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121723

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurt, Barış, and Firat Kurt. 2025. "AI-Powered Structural and Co-Expression Analysis of Potato (Solanum tuberosum) StABCG25 Transporters Under Drought: A Combined AlphaFold, WGCNA, and MD Approach" Biology 14, no. 12: 1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121723

APA StyleKurt, B., & Kurt, F. (2025). AI-Powered Structural and Co-Expression Analysis of Potato (Solanum tuberosum) StABCG25 Transporters Under Drought: A Combined AlphaFold, WGCNA, and MD Approach. Biology, 14(12), 1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121723