Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization, and Expression Profiles of TLR Genes in Darkbarbel Catfish (Pelteobagrus vachelli) Following Aeromonas hydrophila Infection

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Genome-Wide Identification of TLR Genes in P. vachellii

2.2. Experimental Animals and Rearing Conditions

2.3. Pathogen Preparation and Infection Experiment

2.4. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Genome-Wide Presence of TLR Genes in Various Teleost Species

3.2. Molecular Characterization of TLR Genes in P. vachelli (Pv)

3.3. Gene Structures of TLRs in P. vachelli

3.4. Conserved Domain Structures in the PvTLR Proteins

3.5. Predicted Tertiary Structures of the PvTLRs

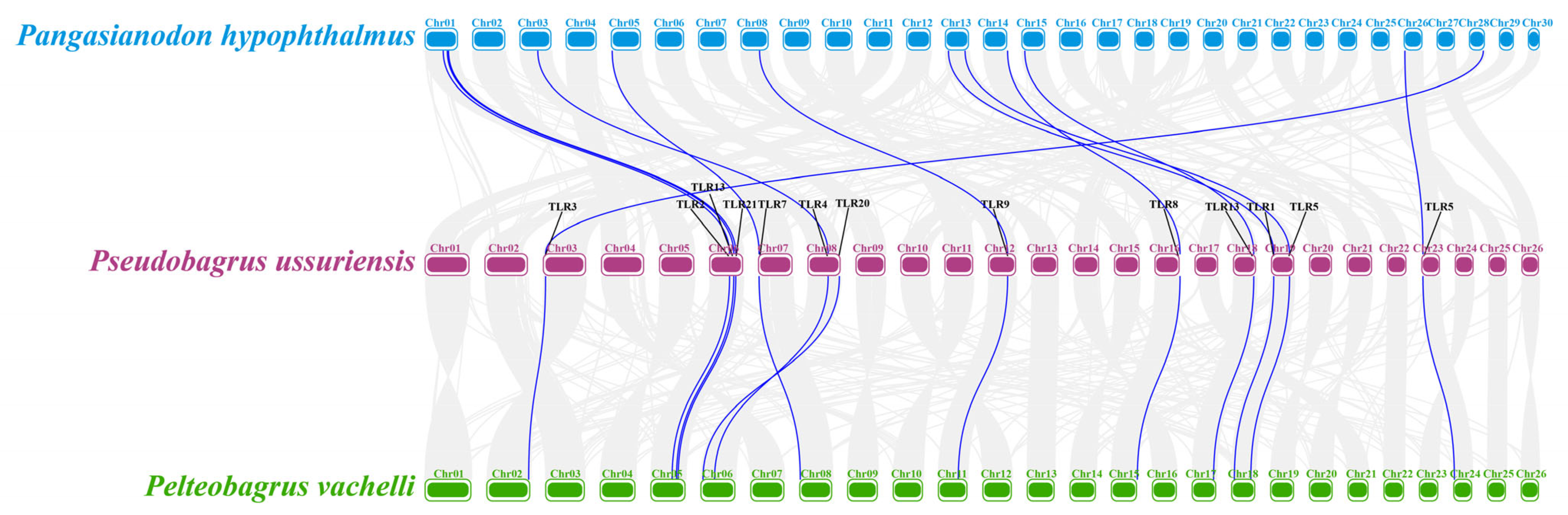

3.6. Collinearity of TLR Genes for Potential Conserved Chromosomal Organization in Teleost Fishes

3.7. Phylogeny Reveals Evolutionary Stability of TLR Subfamilies in Teleost Fishes

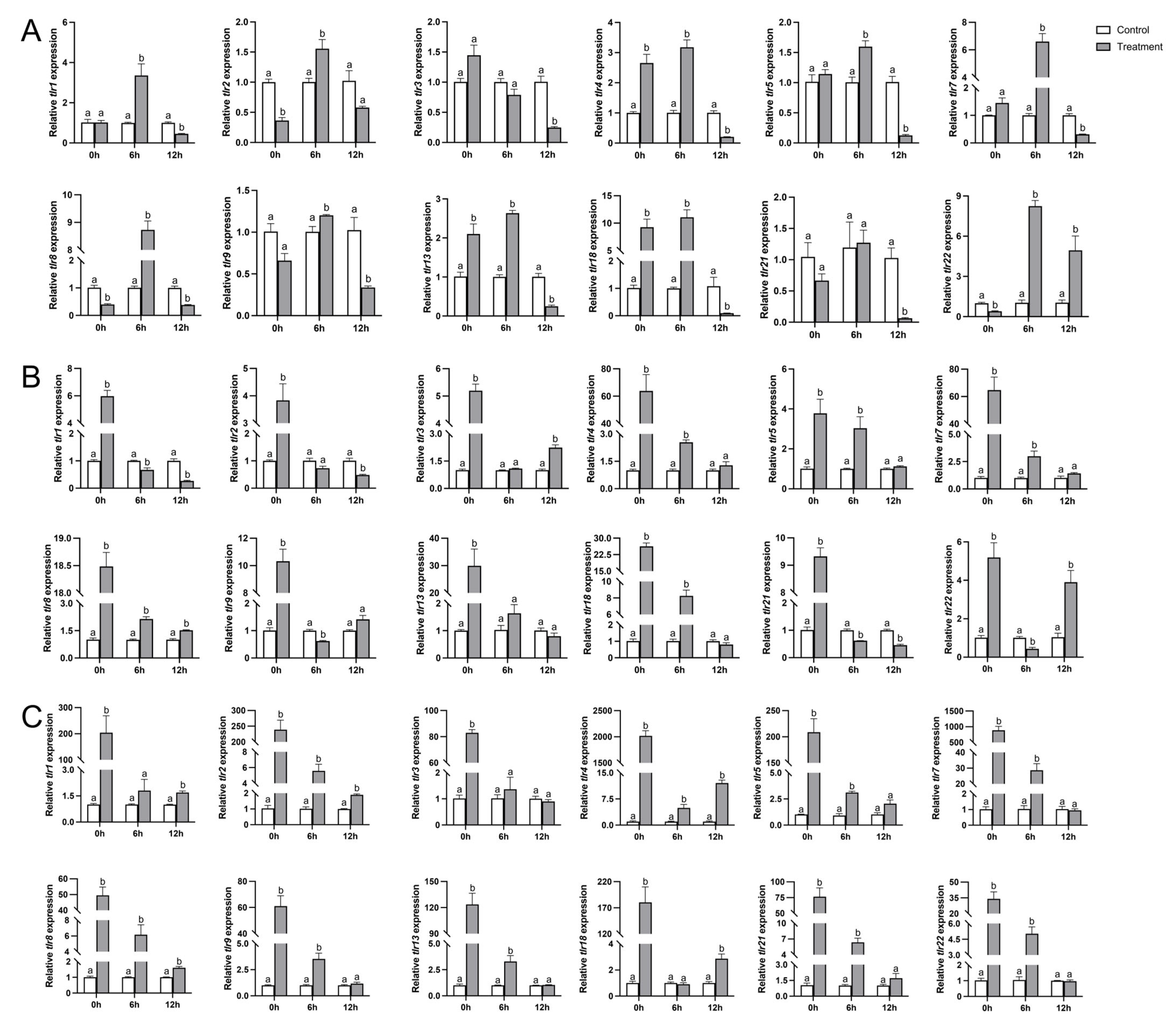

3.8. Transcription of TLR Genes in P. vachelli After Infection by A. hydrophila

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Wang, T.; Liu, W.; Yin, D.; Lai, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, K.; Ji, J.; Yin, S. A high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly of Pelteobagrus vachelli provides insights into its environmental adaptation and population history. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1050192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, Q.; Li, M.; Lan, Y.; Song, Z. Integrated miRNA and mRNA sequencing reveals the sterility mechanism in hybrid yellow catfish resulting from Pelteobagrus fulvidraco (♀) × Pelteobagrus vachelli (♂). Animals 2024, 14, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, S.; Li, H.; Qiao, G.; Li, Z. First case of Edwardsiella ictaluri infection in China farmed yellow catfish Pelteobagrus fulvidraco. Aquaculture 2009, 292, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Gong, Q.; Wen, Z.; Yuan, D.; Shao, T.; Wang, J.; Li, H. Transcriptome analysis of the spleen of the darkbarbel catfish Pelteobagrus vachellii in response to Aeromonas hydrophila infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017, 70, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, C.; Folch, H.; Enriquez, R.; Moran, G. Innate and adaptive immunity in teleost fish: A review. Vet. Med. 2011, 56, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnadóttir, B. Innate immunity of fish (overview). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2006, 20, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell 2010, 140, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: Update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palti, Y. Toll-like receptors in bony fish: From genomics to function. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2011, 35, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laing, K.J.; Hansen, J.D. Fish T cells: Recent advances through genomics. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2011, 35, 1282–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chen, D.; Lin, S.; Li, S.; Deng, B.; Chen, W.; Zhan, H.; Deng, Z.; Li, Q.; Han, C. Molecular characterization and expression analysis of four toll-like receptors (TLR) genes: TLR2, TLR5S, TLR14 and TLR22 in Mastacembelus armatus under Aeromonas veronii infection. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2025, 165, 105345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J. Toll-like receptor signaling in teleosts. Sci. China Life Sci. 2025, 68, 1889–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Wu, M.; Dai, C.; Li, L.; Yuan, J. Duplicated TLRs possess sub- and neo-functionalization to broaden their ligand recognition in crucian carp (Carassius auratus). Eur. J. Immunol. 2025, 55, e202451360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, N.E.; Hall, J.K.; Odom, G.L.; Phelps, M.P.; Andrus, C.R.; Hawkins, R.D.; Hauschka, S.D.; Chamberlain, J.R.; Chamberlain, J.S. Muscle-specific CRISPR/Cas9 dystrophin gene editing ameliorates pathophysiology in a mouse model for duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, C.; Gong, Q.; Wen, Z.; Yuan, D.; Shao, T.; Li, H. Molecular characterization and expression of toll-like receptor 5 genes from Pelteobagrus vachellii. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 75, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, S.C.; Luciani, A.; Eddy, S.R.; Park, Y.; Lopez, R.; Finn, R.D. HMMER web server: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W200–W204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armwood, A.R.; Griffin, M.J.; Richardson, B.M.; Wise, D.J.; Ware, C.; Camus, A.C. Pathology and virulence of Edwardsiella tarda, Edwardsiella piscicida, and Edwardsiella anguillarum in channel (Ictalurus punctatus), blue (Ictalurus furcatus), and channel × blue hybrid catfish. J. Fish Dis. 2022, 45, 1683–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zeng, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Fan, Y.; Shi, Q.; Song, Z. Characterization and expression profiles of cGAS (cyclic GMP-AMP synthase) and STING (stimulator of interferon) genes in various immune tissues of hybrid yellow catfish under bacterial infections. Aquac. Rep. 2024, 37, 102238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: The independent samples t-test. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2019, 44, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.K. Understanding one-way ANOVA using conceptual figures. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2017, 70, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, M.; Ghosh, J.K.; Tokdar, S.T. A comparison of the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure with some Bayesian rules for multiple testing. Inst. Math. Stat. (IMS) Collect. 2008, 1, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitteer, D.R.; Greer, B.D. Using graphpad prism’s heat maps for efficient, fine-grained analyses of single-case data. Behav. Anal. Pract. 2022, 15, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, A.Y.M.; Kiron, V.; Dopazo, J.; Fernandes, J.M.O. Diversification of the expanded teleost-specific toll-like receptor family in Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua. BMC Evol. Biol. 2012, 12, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujita, T.; Ishii, A.; Tsukada, H.; Matsumoto, M.; Che, F.-S.; Seya, T. Fish soluble Toll-like receptor (TLR)5 amplifies human TLR5 response via physical binding to flagellin. Vaccine 2006, 24, 2193–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Chu, Q.; Cui, J.; Zhao, X. The inducible microRNA-203 in fish represses the inflammatory responses to Gram-negative bacteria by targeting IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 4. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 1386–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyam, M.; Gupta, S.K.; Sarkar, B.; Sharma, T.R.; Pattanayak, A. Variation in selection constraints on teleost TLRs with emphasis on their repertoire in the walking catfish, Clarias batrachus. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Yan, X.; Yang, N.; Fu, Q.; Xue, T.; Zhao, S.; Hu, J.; Li, Q.; Song, L.; Zhang, X.; et al. Genome-wide characterization of Toll-like receptors in black rockfish Sebastes schlegelii: Evolution and response mechanisms following Edwardsiella tarda infection. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 949–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, L.; Yu, Y.; Kong, W.; Yin, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Z. The change of teleost skin commensal microbiota is associated with skin mucosal transcriptomic responses during parasitic infection by Ichthyophthirius multifillis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, e67579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, M.Á. An overview of the immunological defenses in fish skin. ISRN Immunol. 2012, 2012, 853470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Feng, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Hu, M.; Xu, P.; Jiang, Y. Genome-wide characterization of Toll-like receptor gene family in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) and their involvement in host immune response to Aeromonas hydrophila infection. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2017, 24, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primer Name | Primer Sequence (5′-3′) | Amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin F | GGACCAATCAGACGAAGCGA | 105 |

| β-actin R | TCAGAGTGGCAGCTTAACCG | |

| TLR1 F | TTTGCTAGCCACGAGCTGATG | 120 |

| TLR1 R | TCTGGCCAGCATTGCCTTTA | |

| TLR2 F | AGCTCCAGTTCGGTAACACG | 149 |

| TLR2 R | AACTGCCCTGATGGGTTGAG | |

| TLR3 F | ACCTTCTCCGTTTCGACCAC | 87 |

| TLR3 R | TCGAGCAAGCCGTTTCTGAT | |

| TLR4 F | CAAGGCAGTACTGGAGCCAT | 89 |

| TLR4 R | AGTTCCAGTATGATGGGCGA | |

| TLR5 F | GAGGCTGACGCTGTTCATCT | 136 |

| TLR5 R | TGGGCTTCCATCCACGAATC | |

| TLR7 F | GGACGACACTTCCCCAATGT | 103 |

| TLR7 R | ATTTTTGCAGCTTCGTGCGT | |

| TLR8 F | AGACGTAAGAGCTGGTTGGC | 95 |

| TLR8 R | GGTCCGCCAGATAAGAGACG | |

| TLR9 F | GCAGATGCTCTGGGTCATGT | 129 |

| TLR9 R | ATGTTTCCATCGCTGTCCGT | |

| TLR13 F | ATTGTGGTTTGTCTGGCGGT | 107 |

| TLR13 R | CCCTGGCAGAGGATAGCAAA | |

| TLR18 F | CAGAGCGGGTAACAATCCGT | 132 |

| TLR18 R | AGCAGGTCTTGAGGGTGGTA | |

| TLR21 F | ACGCTAATGCAGACAGAGTCC | 130 |

| TLR21 R | GCCATATTTGTCAAAGTGGATGGA | |

| TLR22 F | GACACCAGGGTCTTCTGGCA | 142 |

| TLR22 R | TCCTCAGCACTCTGCAGATAATTT |

| Gene Name | NCBI Accession Number | Full Length (bp) | ORF (bp) | 5′-UTR (bp) | 3′-UTR (bp) | Protein Accession Number | Deduced Protein (aa) | Molecular Weight (kDa) | Theoretical pI | Signal Peptide | Transmembrane |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR1 | XM_060892079.1 | 2924 | 2514 | 200 | 210 | XP_060748062.1 | 837 | 95.3 | 7.18 | No | Yes (1) |

| TLR2 | XM_060860014.1 | 2656 | 2370 | 193 | 93 | XP_060715997.1 | 789 | 90.8 | 6.33 | Yes | Yes (1) |

| TLR3 | XM_060864636.1 | 3551 | 2718 | 234 | 599 | XP_060720619.1 | 905 | 103.6 | 7.07 | Yes | Yes (1) |

| TLR4 | XM_060872308.1 | 2466 | 2089 | 326 | 17 | XP_060728291.1 | 821 | 93.9 | 6.97 | Yes | Yes (1) |

| TLR5 | XM_060892327.1 | 3445 | 2655 | 221 | 569 | XP_060748310.1 | 884 | 102.0 | 5.63 | Yes | Yes (1) |

| TLR7 | XM_060875633.1 | 3274 | 3198 | 10 | 66 | XP_060731616.1 | 1065 | 123.0 | 7.14 | Yes | No |

| TLR8 | XM_060877162.1 | 3863 | 3264 | 137 | 462 | XP_060733145.1 | 1087 | 125.3 | 7.57 | Yes | Yes (1) |

| TLR9 | XM_060881940.1 | 4456 | 3201 | 99 | 1156 | XP_060737923.1 | 1066 | 122.7 | 7.15 | Yes | Yes (1) |

| TLR13 | XM_060870764.1 | 3703 | 2868 | 188 | 647 | XP_060726747.1 | 955 | 110.0 | 6.15 | No | Yes (2) |

| TLR18 | XM_060870249.1 | 4164 | 2586 | 85 | 1493 | XP_060726232.1 | 861 | 98.9 | 5.84 | Yes | Yes (1) |

| TLR21 | XM_060870646.1 | 3476 | 2952 | 238 | 288 | XP_060726629.1 | 983 | 104.6 | 7.29 | Yes | Yes (1) |

| TLR22 | XM_060890409.1 | 3523 | 2892 | 127 | 504 | XP_060746392.1 | 963 | 110.7 | 7.59 | Yes | Yes (3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wen, Z.; Guo, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, Y.; Lv, Y.; Shi, Q.; Guo, S. Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization, and Expression Profiles of TLR Genes in Darkbarbel Catfish (Pelteobagrus vachelli) Following Aeromonas hydrophila Infection. Biology 2025, 14, 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121724

Wen Z, Guo L, Chen J, Chen Q, Li Y, Lv Y, Shi Q, Guo S. Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization, and Expression Profiles of TLR Genes in Darkbarbel Catfish (Pelteobagrus vachelli) Following Aeromonas hydrophila Infection. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121724

Chicago/Turabian StyleWen, Zhengyong, Lisha Guo, Jianchao Chen, Qiyu Chen, Yanping Li, Yunyun Lv, Qiong Shi, and Shengtao Guo. 2025. "Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization, and Expression Profiles of TLR Genes in Darkbarbel Catfish (Pelteobagrus vachelli) Following Aeromonas hydrophila Infection" Biology 14, no. 12: 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121724

APA StyleWen, Z., Guo, L., Chen, J., Chen, Q., Li, Y., Lv, Y., Shi, Q., & Guo, S. (2025). Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization, and Expression Profiles of TLR Genes in Darkbarbel Catfish (Pelteobagrus vachelli) Following Aeromonas hydrophila Infection. Biology, 14(12), 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121724