Comparative Genomic and Microenvironmental Profiles of Hereditary and Sporadic TNBC in Colombian Women

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Background

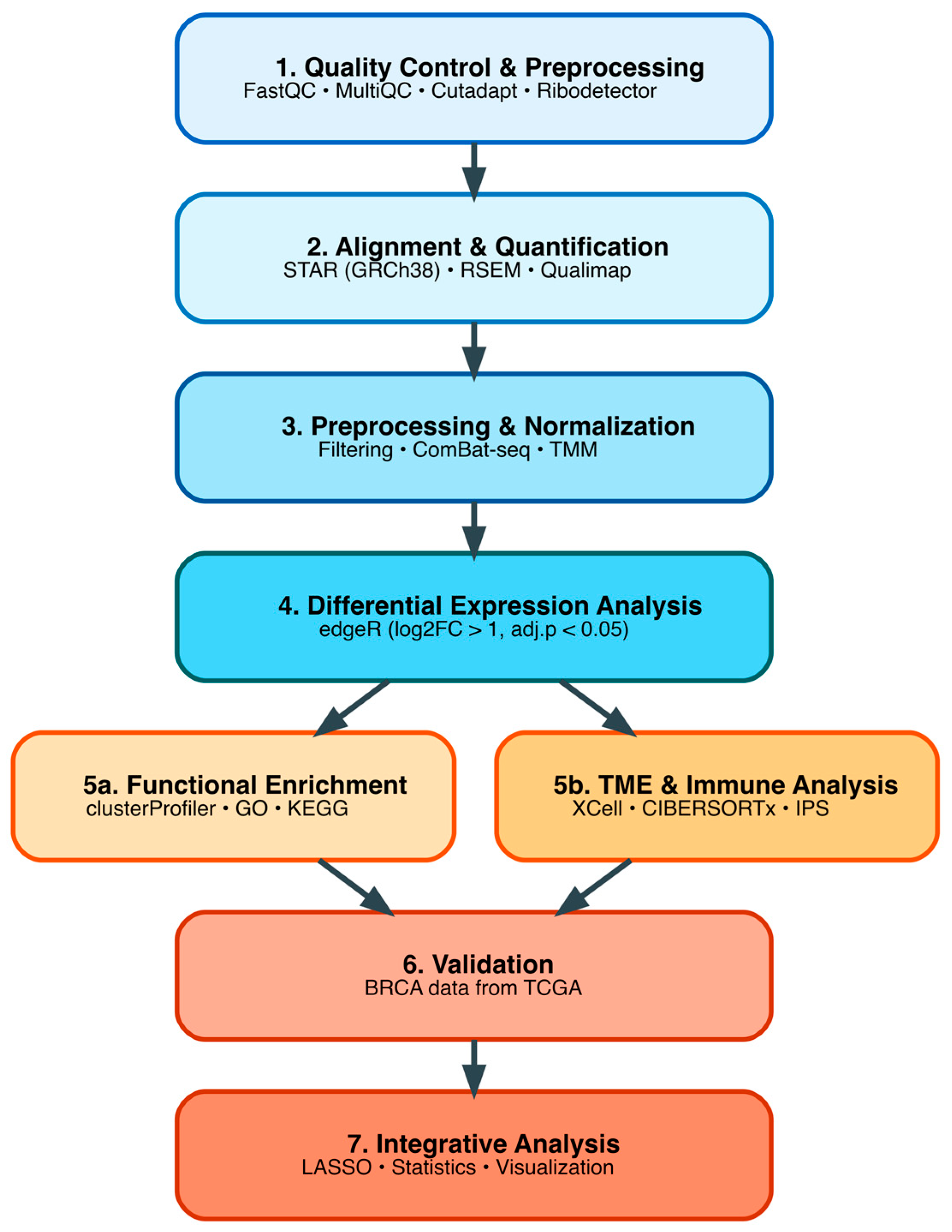

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Samples

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Study Power and Sample Size

2.4. Sample Collection and Sequencing

2.5. Bioinformatic Processing and Quality Control of RNA-Seq Data

2.6. Differential Gene Expression Analysis in Colombian Cohort

2.7. Functional Enrichment Analysis

2.8. Tumor Microenvironment Deconvolution Analysis in Colombian Cohort

2.9. DEG Validation Analysis Using TCGA TNBC Cohort

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and Pathological Characteristics of Colombian Cohort

3.2. Bioinformatic Data Preprocessing and Quality Control of Sequences

3.3. Differential Gene Expression Analysis in Colombian Women Cohort

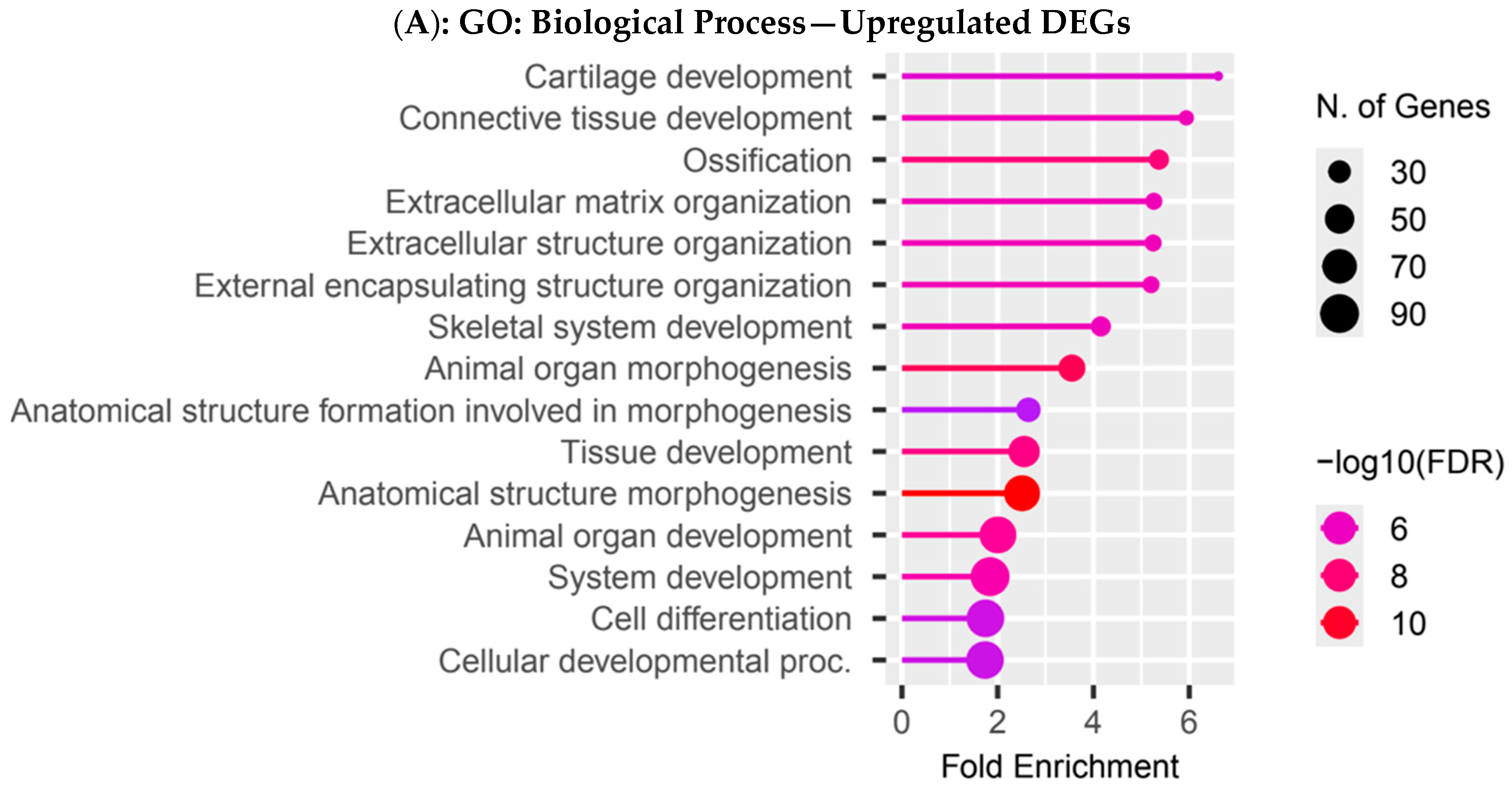

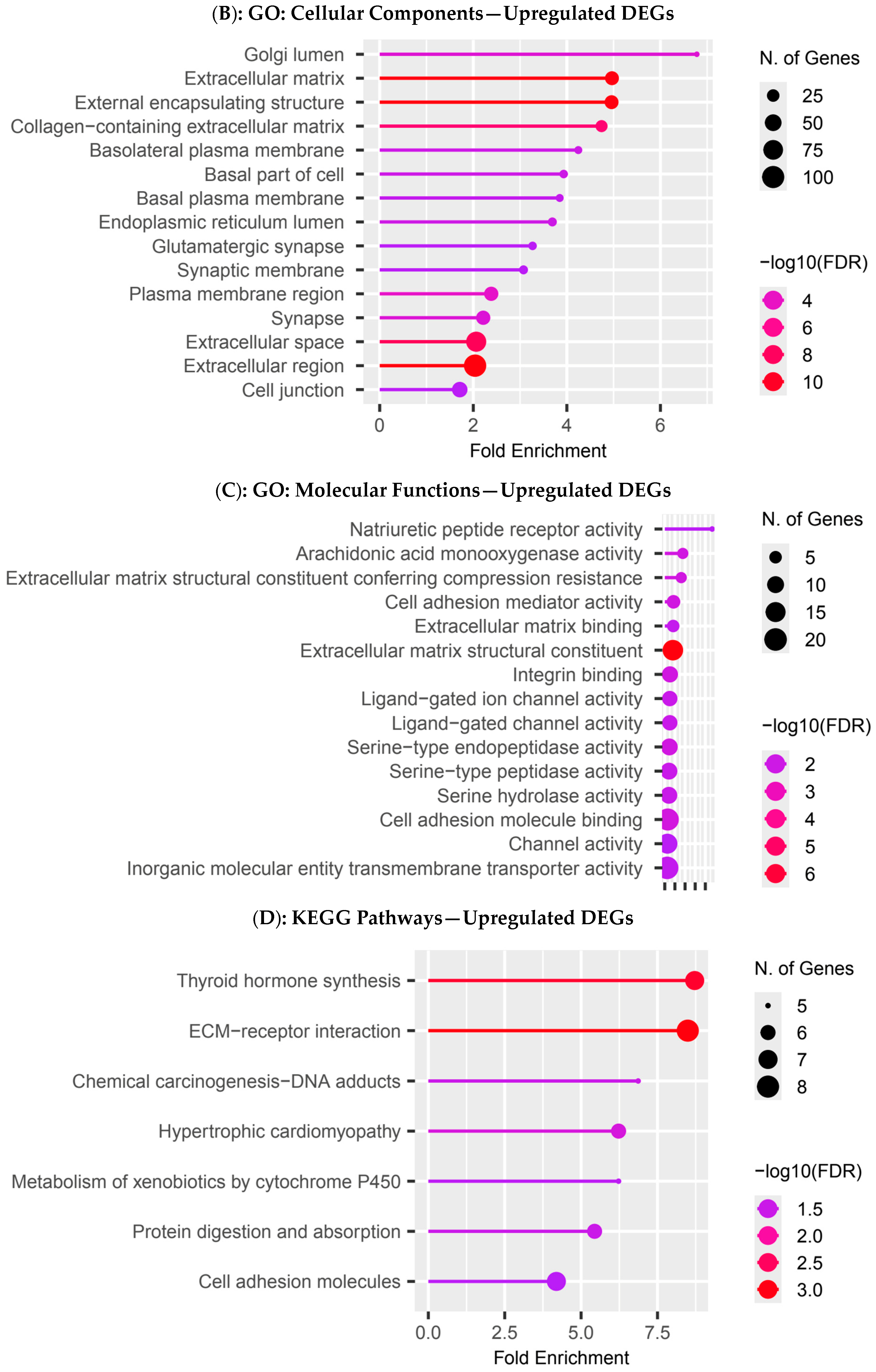

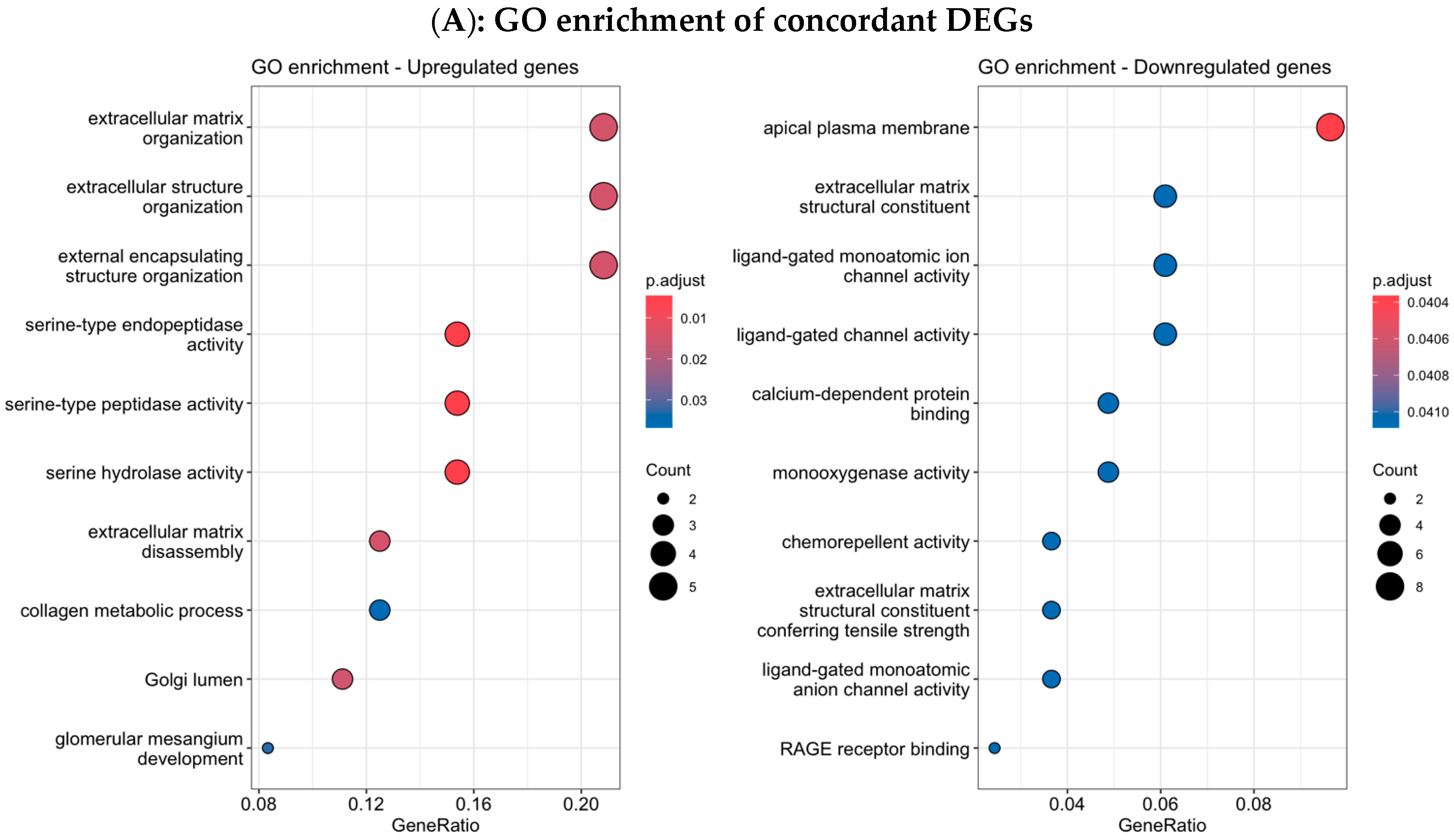

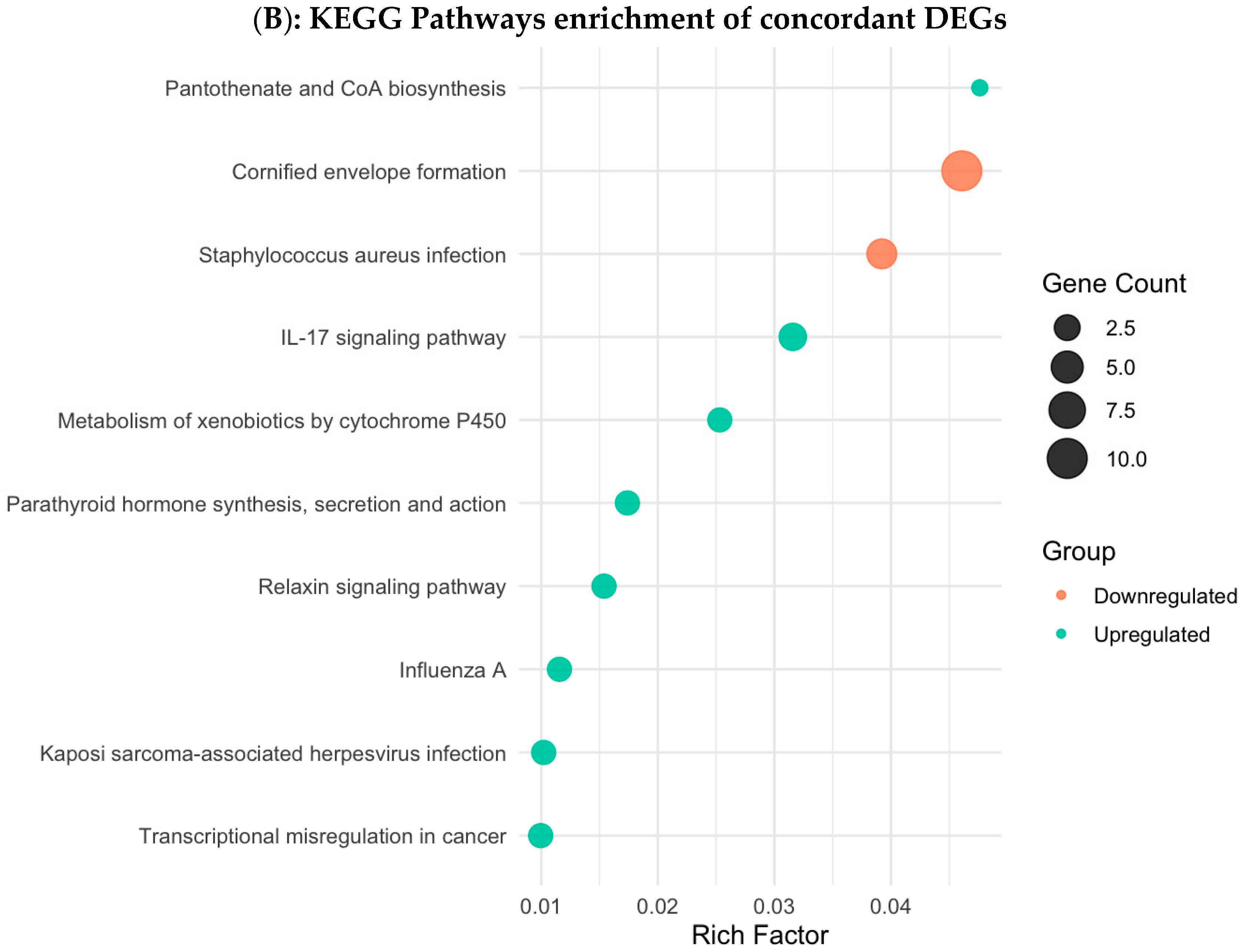

3.4. Functional Enrichment Analysis in Colombian Women Cohort

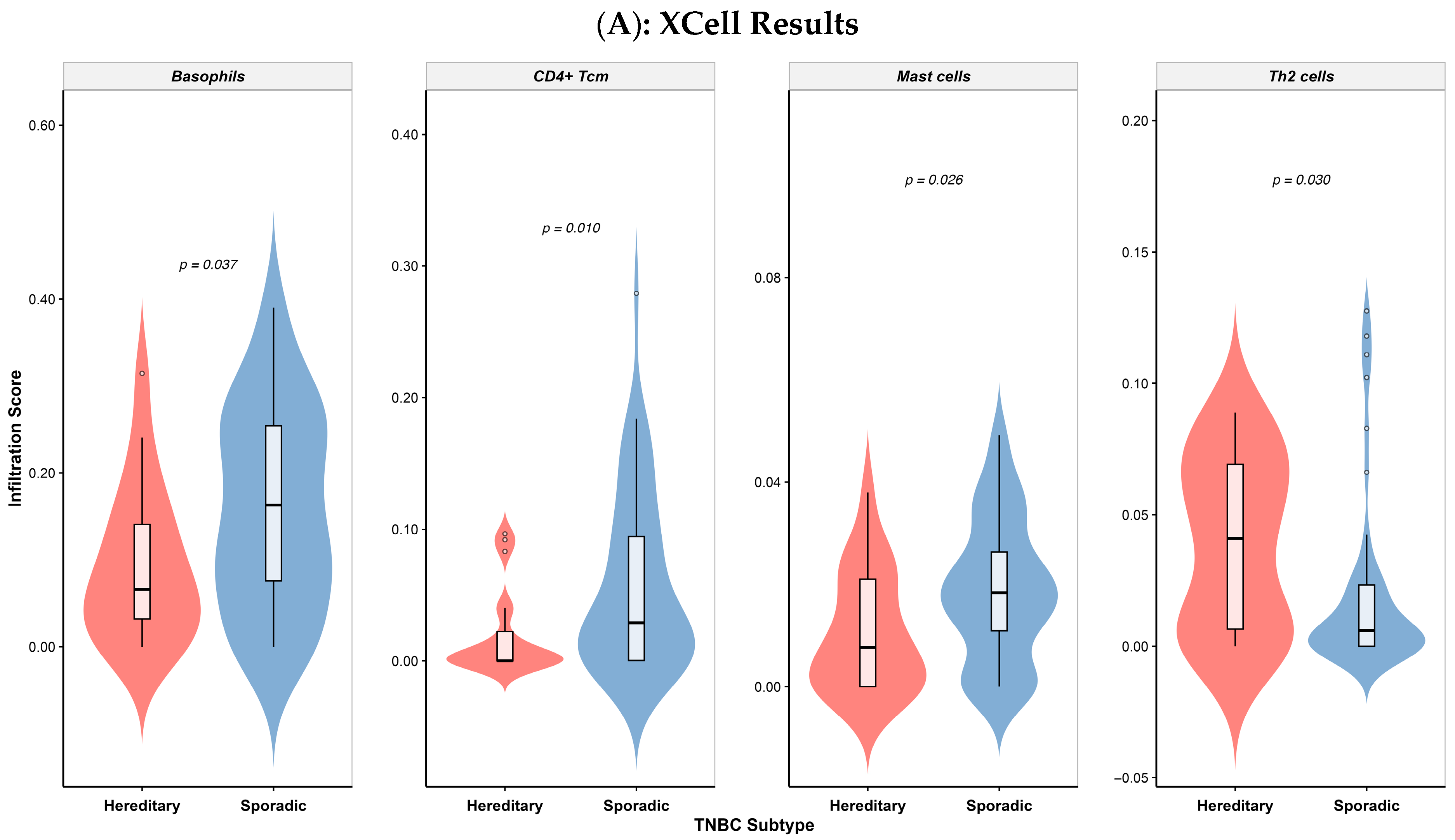

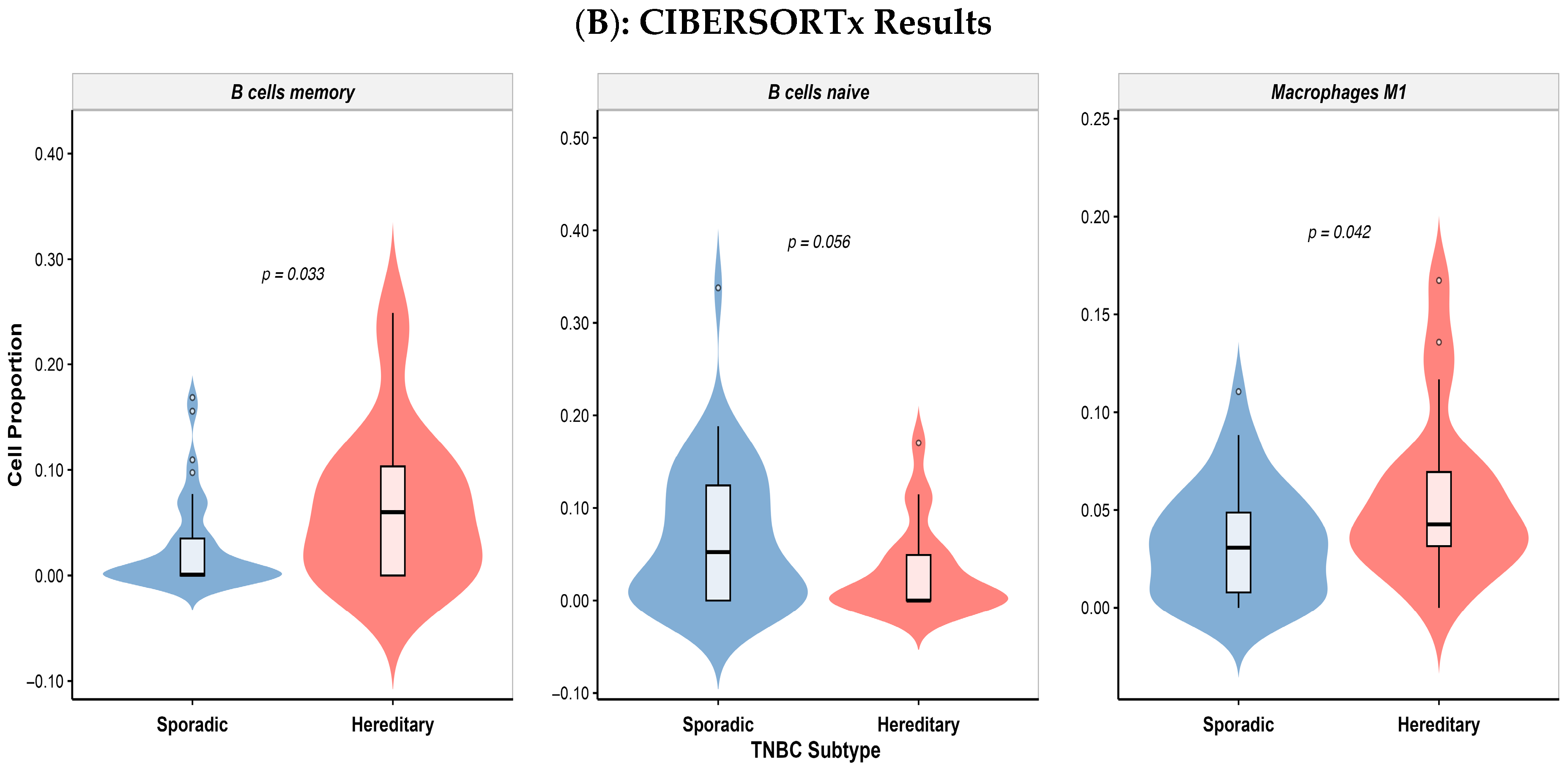

3.5. Differential Immune Cell Infiltration in Colombian Patients

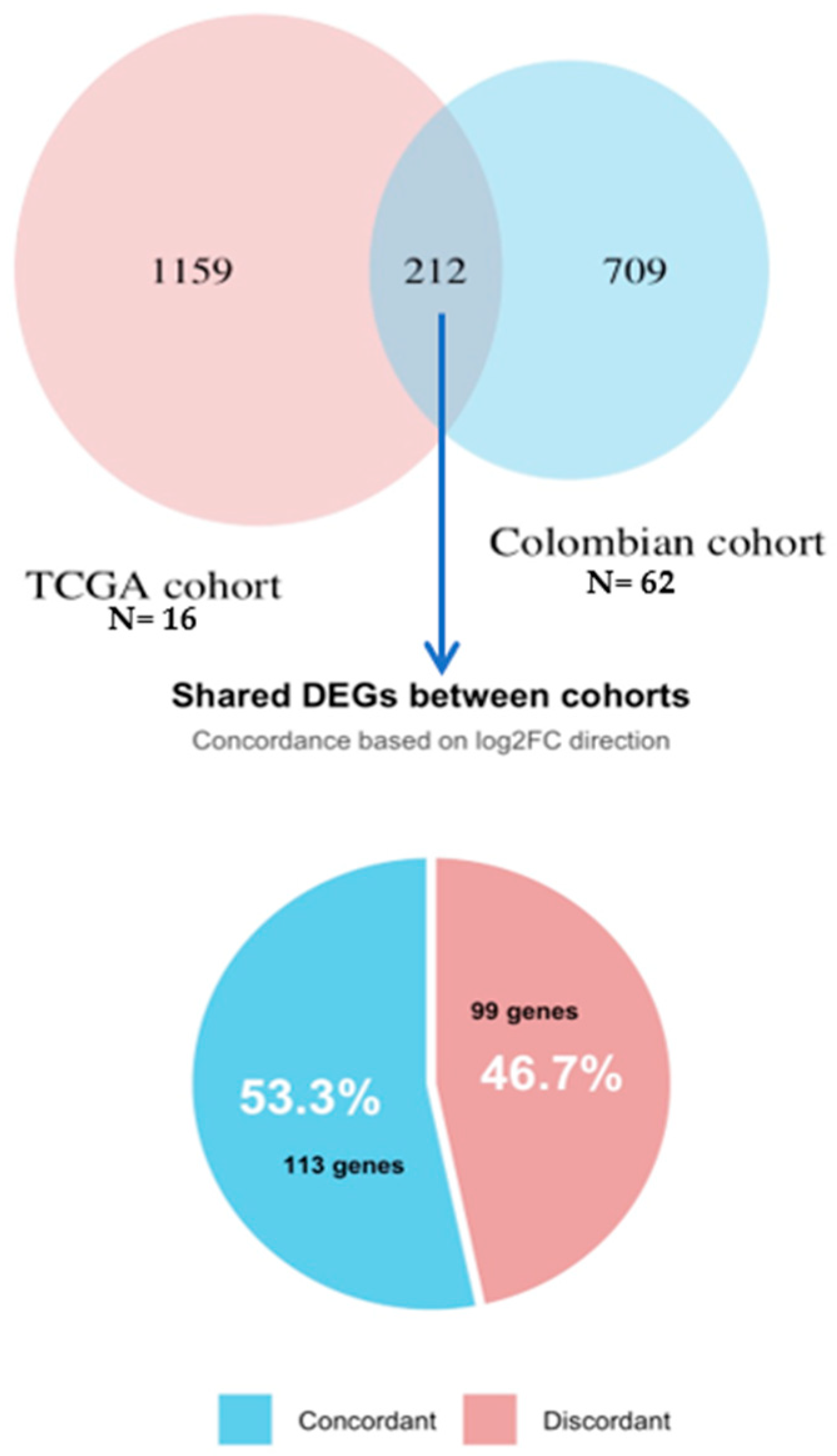

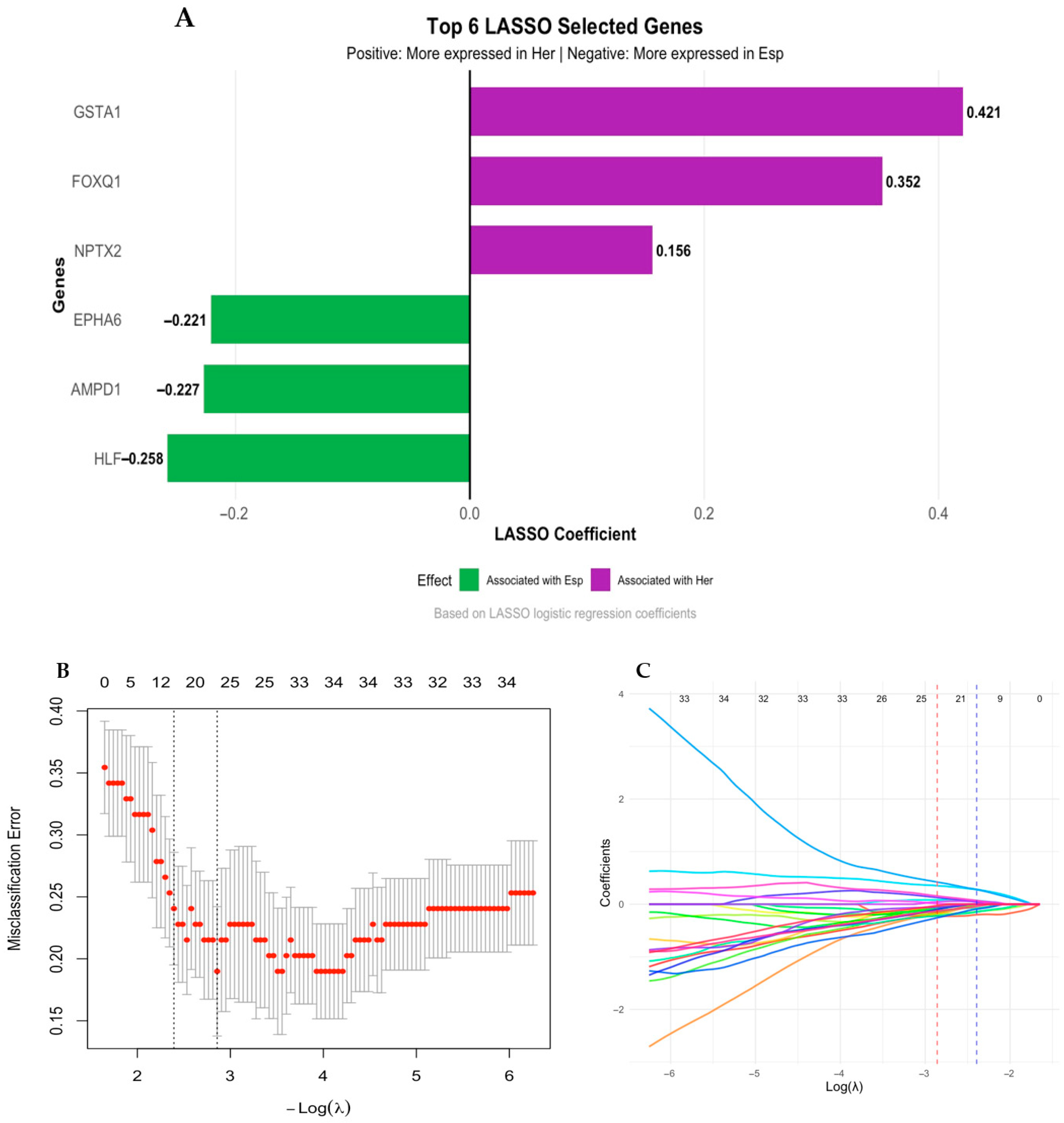

3.6. Validation Using TCGA Breast Cancer Cohort

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Future Perspectives and Recommendations

5.2. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BC | Breast Cancer |

| TNBC | Triple-Negative Breast Cancer |

| H-TNBC | Hereditary Triple-Negative Breast Cancer |

| S-TNBC | Sporadic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer |

| ER | Estrogen Receptor |

| PR | Progesterone Receptor |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| HRR | Homologous Recombination Repair |

| TILs | Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| Tcm | Central Memory CD4+ T cells |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| P | Pathogenic Variants |

| LP | Likely Pathogenic Variants |

| FFPE | Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded |

| RSEM | RNA-Seq by Expectation-Maximization |

| TMM | Trimmed Mean of M-values |

| CPM | Counts Per Million |

| DEGs | Differentially Expressed Genes |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Million |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| NCI-Col | Colombian National Cancer Institute |

| BP | Biological Process |

| CC | Cellular Component |

| MF | Molecular Functions |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| TMB | Tumor Mutational Burden |

| Tregs | Regulatory T cells |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

References

- Perou, C.M.; Sørile, T.; Eisen, M.B.; Van De Rijn, M.; Jeffrey, S.S.; Ress, C.A.; Pollack, J.R.; Ross, D.T.; Johnsen, H.; Akslen, L.A.; et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2000, 406, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørlie, T.; Perou, C.M.; Tibshirani, R.; Aas, T.; Geisler, S.; Johnsen, H.; Hastie, T.; Eisen, M.B.; van de Rijn, M.; Jeffrey, S.S.; et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10869–10874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waks, A.G.; Winer, E.P. Breast Cancer Treatment: A Review. JAMA—J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2019, 321, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Castro, A.C.; Lin, N.U.; Polyak, K. Insights into molecular classifications of triple-negative breast cancer: Improving patient selection for treatment. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 176–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldhirsch, A.; Winer, E.P.; Coates, A.S.; Gelber, R.D.; Piccart-Gebhart, M.; Thürlimann, B.; Senn, H.-J.; Panel members. Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: Highlights of the st gallen international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast Cancer 2013. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 2206–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, G.; Frasci, G.; Chirico, A.; Esposito, E.; Siani, C.; Saturnino, C.; Arra, C.; Ciliberto, G.; Giordano, A.; D’Aiuto, M. Triple negative breast cancer: Looking for the missing link between biology and treatments. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 26560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporikova, Z.; Koudelakova, V.; Trojanec, R.; Hajduch, M. Genetic Markers in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 2018, 18, e841–e850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, R.; Trudeau, M.; Pritchard, K.I.; Hanna, W.M.; Kahn, H.K.; Sawka, C.A.; Lickley, L.A.; Rawlinson, E.; Sun, P.; Narod, S.A. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Clinical Features and Patterns of Recurrence. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 4429–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, C.; Porsch, M.; Stückrath, K.; Kaufhold, S.; Staege, M.S.; Hanf, V.; Lantzsch, T.; Uleer, C.; Peschel, S.; John, J.; et al. Identifying High-Risk Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Patients by Molecular Subtyping. Breast Care 2021, 16, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareja, F.; Geyer, F.C.; Marchiò, C.; Burke, K.A.; Weigelt, B.; Reis-Filho, J.S. Triple-negative breast cancer: The importance of molecular and histologic subtyping, and recognition of low-grade variants. NPJ Breast Cancer 2016, 2, 16036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millikan, R.C.; Newman, B.; Tse, C.K.; Moorman, P.G.; Conway, K.; Dressler, L.G.; Smith, L.V.; Labbok, M.H.; Geradts, J.; Bensen, J.T.; et al. Epidemiology of basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2008, 109, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihemelandu, C.U.; Leffall, L.S.D.; Dewitty, R.L.; Naab, T.J.; Mezghebe, H.M.; Makambi, K.H.; Adams-Campbell, L.; Frederick, W.A. Molecular Breast Cancer Subtypes in Premenopausal and Postmenopausal African-American Women: Age-Specific Prevalence and Survival. J. Surg. Res. 2007, 143, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey-Vargas, L.; Sanabria-Salas, M.C.; Fejerman, L.; Serrano-Gomez, S.J. Risk factors for triple-negative breast cancer among Latina women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019, 28, 1771–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, N.U.; Claus, E.; Sohl, J.; Razzak, A.R.; Arnaout, A.; Winer, E.P. Sites of distant recurrence and clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer 2008, 113, 2638–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domagala, P.; Hybiak, J.; Cybulski, C.; Lubinski, J. BRCA1/2-negative hereditary triple-negative breast cancers exhibit BRCAness. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 1545–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolou, P.; Fostira, F. Hereditary breast cancer: The Era of new susceptibility genes. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 747318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchley, D.P.; Albarracin, C.T.; Lopez, A.; Valero, V.; Amos, C.I.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Arun, B.K. Clinical and Pathologic Characteristics of Patients With BRCA-Positive and BRCA-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 4282–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.C.; Reis-Filho, J.S. Basal-like breast cancer and the BRCA1 phenotype. Oncogene 2006, 25, 5846–5853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogony, J.; Hoskin, T.L.; Stallings-Mann, M.; Winham, S.; Brahmbhatt, R.; Arshad, M.A.; Kannan, N.; Peña, A.; Allers, T.; Brown, A.; et al. Immune cells are increased in normal breast tissues of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 197, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizides, S.; Constantinidou, A. Triple negative breast cancer: Immunogenicity, tumor microenvironment, and immunotherapy. Front. Genet. 2023, 13, 1095839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.W.; Tan, Z.C.; Ng, P.S.; Zabidi, M.M.A.; Nur Fatin, P.; Teo, J.Y.; Hasan, S.N.; Islam, T.; Teoh, L.Y.; Jamaris, S.; et al. Gene expression signature for predicting homologous recombination deficiency in triple-negative breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2024, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dameri, M.; Ferrando, L.; Cirmena, G.; Vernieri, C.; Pruneri, G.; Ballestrero, A.; Zoppoli, G. Multi-Gene Testing Overview with a Clinical Perspective in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanabria-Salas, M.C.; Rivera-Herrera, A.L.; Manotas, M.C.; Guevara, G.; Gómez, A.M.; Medina, V.; Tapiero, S.; Huertas, A.; Nuñez, M.; Torres, M.Z.; et al. Building a hereditary cancer program in Colombia: Analysis of germline pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants spectrum in a high-risk cohort. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2025, 33, 913–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.W.; Orelli, B.J.; Yamazoe, M.; Minn, A.J.; Takeda, S.; Bishop, D.K. RAD51 up-regulation bypasses BRCA1 function and is a common feature of BRCA1-deficient breast tumors. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 9658–9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenemans, P.; Verstraeten, R.A.; Verheijen, R.H.M. Oncogenic pathways in hereditary and sporadic breast cancer. Maturitas 2004, 49, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, C.; Wang, X. Classification of triple-negative breast cancers based on Immunogenomic profiling. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas-Caro, C.A.; Ramirez, M.A.; Gonzalez-Torres, H.J.; Sanabria-Salas, M.C.; Serrano-Gómez, S.J. Immune Lymphocyte Infiltrate and its Prognostic Value in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 910976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas-Caro, C.A.; Ramírez, M.A.; Rey-Vargas, L.; Bejarano-Rivera, L.M.; Ballen, D.F.; Nuñez, M.; Mejía, J.C.; Sua-Villegas, L.F.; Cock-Rada, A.; Zabaleta, J.; et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are a prognosis biomarker in Colombian patients with triple negative breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, X. A Comprehensive Immunologic Portrait of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 11, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Lu, D.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bu, H.; Zheng, H. Immune profiles of tumor microenvironment and clinical prognosis among women with triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019, 28, 1977–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayaman, R.W.; Saad, M.; Thorsson, V.; Hu, D.; Hendrickx, W.; Roelands, J.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Mokrab, Y.; Farshidfar, F.; Kirchhoff, T.; et al. Germline genetic contribution to the immune landscape of cancer. Immunity 2021, 54, 367–386.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Nagarathinam, R.; Arisi, M.F.; Gerratana, L.; Winn, J.S.; Slifker, M.; Pei, J.; Cai, K.Q.; Hasse, Z.; Obeid, E.; et al. Genetic variants and tumor immune microenvironment: Clues for targeted therapies in inflammatory breast cancer (ibc). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedenfalk, I.; Duggan, D.; Chen, Y.; Radmacher, M.; Bittner, M.; Simon, R.; Meltzer, P.; Gusterson, B.; Esteller, M.; Raffeld, M.; et al. Gene-Expression Profiles in Hereditary Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Ek, W.E.; Whiteman, D.; Vaughan, T.L.; Spurdle, A.B.; Easton, D.F.; Pharoah, P.D.; Thompson, D.J.; Dunning, A.M.; Hayward, N.K.; et al. Most common ‘sporadic’ cancers have a significant germline genetic component. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 6112–6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhani, S.R.; Jacquemier, J.; Sloane, J.P.; Gusterson, B.A.; Anderson, T.J.; Van De Vijver, M.J.; Farid, L.M.; Venter, D.; Antoniou, A.; Storfer-Isser, A.; et al. Multifactorial Analysis of Differences Between Sporadic Breast Cancers and Cancers Involving BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1998, 90, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, M.R. Pathology of familial breast cancer: Differences between breast cancers in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and sporadic cases. Lancet 1997, 349, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedenfalk, I.A. Gene Expression Profiling of Hereditary and Sporadic Ovarian Cancers Reveals Unique BRCA1 and BRCA2 Signatures. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2002, 94, 960–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudaladava, V.; Jarząb, M.; Stobiecka, E.; Chmielik, E.; Simek, K.; Huzarski, T.; Lubiński, J.; Pamuła, J.; Pękala, W.; Grzybowska, E.; et al. Gene Expression Profiling in Hereditary, BRCA1-linked Breast Cancer. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2006, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, M.C.S.; Duran, A.M.P.; Rivera, A.L.; Hurtado, D.G.; Franco, D.M.C.; Ortiz, M.A.Q.; Rodríguez, R.S.; Gómez, A.M.; Manotas, M.C.; Maya, R.B.; et al. Criterios para la identificación de síndromes de cáncer de mama hereditarios. Revisión de la literatura y recomendaciones para el Instituto Nacional de Cancerología—Colombia. Rev. Colomb. Cancerol. 2023, 27 (Suppl. S1), 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradishar, W.J.; Moran, M.S.; Abraham, J.; Abramson, V.; Aft, R.; Agnese, D.; Allison, K.H.; Anderson, B.; Bailey, J.; Burstein, H.J.; et al. Breast Cancer, Version 3.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2024, 22, 331–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manotas, M.C.; Rivera, A.L.; Sanabria-Salas, M.C. Variant curation and interpretation in hereditary cancer genes: An institutional experience in Latin America. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2023, 11, e2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aran, D.; Hu, Z.; Butte, A.J. xCell: Digitally portraying the tissue cellular heterogeneity landscape. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.M.; Steen, C.B.; Liu, C.L.; Gentles, A.J.; Chaudhuri, A.A.; Scherer, F.; Khodadoust, M.S.; Esfahani, M.S.; Luca, B.A.; Steiner, D.; et al. Determining cell type abundance and expression from bulk tissues with digital cytometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.S.; de Reyniès, A.; Newman, A.M.; Waterfall, J.J.; Lamb, A.; Petitprez, F.; Lin, Y.; Yu, R.; Guerrero-Gimenez, M.E.; Domanskyi, S.; et al. Community assessment of methods to deconvolve cellular composition from bulk gene expression. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charoentong, P.; Finotello, F.; Angelova, M.; Mayer, C.; Efremova, M.; Rieder, D.; Hack, H.; Trajanoski, Z. Pan-cancer Immunogenomic Analyses Reveal Genotype-Immunophenotype Relationships and Predictors of Response to Checkpoint Blockade. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrot-Zhang, J.; Chambwe, N.; Damrauer, J.S.; Knijnenburg, T.A.; Robertson, A.G.; Yau, C.; Zhou, W.; Berger, A.C.; Huang, K.; Newberg, J.Y.; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of Genetic Ancestry and Its Molecular Correlates in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 639–654.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Dou, H.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, S.; Xiao, M. Extracellular matrix remodeling in tumor progression and immune escape: From mechanisms to treatments. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desterke, C.; Cosialls, E.; Xiang, Y.; Elhage, R.; Duruel, C.; Chang, Y.; Hamaï, A. Adverse Crosstalk between Extracellular Matrix Remodeling and Ferroptosis in Basal Breast Cancer. Cells 2023, 12, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolota, V.; Tzelepi, V.; Piperigkou, Z.; Kourea, H.; Papakonstantinou, E.; Argentou, M.I.; Karamanos, N.K. Epigenetic alterations in triple-negative breast cancer—The critical role of extracellular matrix. Cancers 2021, 13, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, H.; Ivaska, J. Every step of the way: Integrins in cancer progression and metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdembri, D.; Serini, G. The roles of integrins in cancer. Fac. Rev. 2021, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolf, E.L.; Gillis, N.E.; Davidson, C.D.; Cozzens, L.M.; Kogut, S.; Tomczak, J.A.; Frietze, S.; Carr, F.E. Common tumor-suppressive signaling of thyroid hormone receptor beta in breast and thyroid cancer cells. Mol. Carcinog. 2021, 60, 874–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolf, E.L.; Gillis, N.E.; Barnum, M.S.; Beaudet, C.M.; Yu, G.Y.; Tomczak, J.A.; Stein, J.L.; Lian, J.B.; Stein, G.S.; Carr, F.E. The Thyroid Hormone Receptor-RUNX2 Axis: A Novel Tumor Suppressive Pathway in Breast Cancer. Horm. Cancer 2020, 11, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Cheng, S.Y. Thyroid hormone receptors and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2013, 1830, 3928–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C.D.; Gillis, N.E.; Carr, F.E. Thyroid Hormone Receptor Beta as Tumor Suppressor: Untapped Potential in Treatment and Diagnostics in Solid Tumors. Cancers 2021, 13, 4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, N.; Walker, G.C. Mechanisms of DNA damage, repair, and mutagenesis. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2017, 58, 235–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, R.C. The role of DNA adducts in chemical carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 1998, 402, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alli, E.; Sharma, V.B.; Sunderesakumar, P.; Ford, J.M. Defective repair of oxidative DNA damage in triple-negative breast cancer confers sensitivity to inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 3589–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, N.; Tovey, H.; Pearson, A.; Cutts, R.; Toms, C.; Proszek, P.; Hubank, M.; Dowsett, M.; Dodson, A.; Daley, F. Homologous recombination DNA repair deficiency and PARP inhibition activity in primary triple negative breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.Q.; Zhao, X.H.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, T.; Hondermarck, H.; Thorne, R.F.; Zhang, X.D.; Gao, J.N. Exploring neurotransmitters and their receptors for breast cancer prevention and treatment. Theranostics 2023, 13, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, K.; Martirosian, V.; Nakamura, B.N.; Iyer, M.; Julian, A.; Eisenbarth, R.; Shao, L.; Attenello, F.; Neman, J. Neuronal exposure induces neurotransmitter signaling and synaptic mediators in tumors early in brain metastasis. Neuro-Oncology 2022, 24, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacenik, D.; Karagiannidis, I.; Beswick, E.J. Th2 cells inhibit growth of colon and pancreas cancers by promoting anti-tumorigenic responses from macrophages and eosinophils. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Lu, L.; Tang, X.; Huang, S.; Guo, Z.; Tan, G. Breast cancer promotes the expression of neurotransmitter receptor related gene groups and image simulation of prognosis model. SLAS Technol. 2024, 29, 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Meara, T.A.; Tolaney, S.M. Tumor mutational burden as a predictor of immunotherapy response in breast cancer. Oncotarget 2021, 12, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Dong, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, T.; Ma, L.; Qu, M.; Ma, X.; Zhou, X.; He, Q. Comprehensive Analysis of Regulatory Factors and Immune-Associated Patterns to Decipher Common and BRCA1/2 Mutation-Type-Specific Critical Regulation in Breast Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 750897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraya, A.A.; Maxwell, K.N.; Wubbenhorst, B.; Wenz, B.M.; Pluta, J.; Rech, A.J.; Dorfman, L.M.; Lunceford, N.; Barrett, A.; Mitra, N.; et al. Genomic signatures predict the immunogenicity of BRCA-deficient breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 4363–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, A.; Lu, Y.; Han, M.; Ruan, M.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, C.; Shen, K.; Dong, L.; et al. Association of tumor immune infiltration and prognosis with homologous recombination repair genes mutations in early triple-negative breast cancer. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1407837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Saeed, A.F.U.H.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, H.; Xiao, G.G.; Rao, L.; Duo, Y. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, U.; Sarkar, T.; Mukherjee, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Dutta, A.; Dutta, S.; Nayak, D.; Kaushik, S.; Das, T.; Sa, G. Tumor-associated macrophages: An effective player of the tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1295257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFalco, J.; Harbell, M.; Manning-Bog, A.; Baia, G.; Scholz, A.; Millare, B.; Sumi, M.; Zhang, D.; Chu, F.; Dowd, C.; et al. Non-progressing cancer patients have persistent B cell responses expressing shared antibody paratopes that target public tumor antigens. Clin. Immunol. 2018, 187, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancro, M.P.; Tomayko, M.M. Memory B cells and plasma cells: The differentiative continuum of humoral immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2021, 303, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Quintana, A.; Alberts, E.; Hung, M.S.; Boulat, V.; Ripoll, M.M.; Grigoriadis, A. B Cells in Breast Cancer Pathology. Cancers 2023, 15, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Hong, Y.; Qi, P.; Lu, G.; Mai, X.; Xu, S.; He, X.; Guo, Y.; Gao, L.; Jing, Z.; et al. Atlas of breast cancer infiltrated B-lymphocytes revealed by paired single-cell RNA-sequencing and antigen receptor profiling. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Pan, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Jin, Z.; Chen, X. Characterization of Pyroptosis-Related Subtypes via RNA-Seq and ScRNA-Seq to Predict Chemo-Immunotherapy Response in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 788670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, L. Establishment of a novel cytokine-related 8-gene signature for distinguishing and predicting the prognosis of triple-negative breast cancer. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1189361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tung, N.; Garber, J.E.; Hacker, M.R.; Torous, V.; Freeman, G.J.; Poles, E.; Rodig, S.; Alexander, B.; Lee, L.; Collins, L.C.; et al. Prevalence and predictors of androgen receptor and programmed death-ligand 1 in BRCA1-associated and sporadic triple-negative breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2016, 2, 16002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, T. Identification of immune-related signature for the prognosis and benefit of immunotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1067254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Hereditary | Sporadic | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 20 (%) | N = 42 (%) | ||

| Age | 0.334 1 | ||

| ≤50 | 9 (45%) | 23 (62%) | |

| >50 | 11 (55%) | 14 (38%) | |

| BMI | 0.670 2 | ||

| Normal | 10 (50%) | 16 (43%) | |

| Obesity | 2 (10%) | 7 (19%) | |

| Overweight | 8 (40%) | 14 (38%) | |

| Menopausal state | 0.334 1 | ||

| Postmenopausal | 11 (55%) | 14 (38%) | |

| Premenopausal | 9 (45%) | 23 (62%) | |

| Tumor Differentiation | 0.357 2 | ||

| Poorly Differentiated | 17 (89%) | 27 (75%) | |

| Moderately Differentiated | 2 (11%) | 9 (25%) | |

| Ki67 | 0.536 1 | ||

| >50% | 14 (74%) | 28 (85%) | |

| ≤50% | 5 (26%) | 5 (15%) | |

| Laterality | 0.617 1 | ||

| Right | 6 (30%) | 15 (41%) | |

| Left | 14 (70%) | 22 (59%) | |

| T | 0.524 1 | ||

| Tumor ≤ 5 cm | 12 (60%) | 17 (47%) | |

| Tumor > 5 cm | 8 (40%) | 19 (53%) | |

| N | 0.028 2 | ||

| Lymph node involvement (N1-N2) | 11 (55%) | 30 (86%) | |

| No lymph node metastasis | 9 (45%) | 5 (14%) | |

| M | 0.992 2 | ||

| Metastasis | 3 (15%) | 4 (11%) | |

| No Metastasis | 17 (85%) | 31 (89%) | |

| Metastasis location | 0.050 2 | ||

| Regional lymph nodes | 0 (0%) | 4 (100%) | |

| Pleura | 1 (33%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Lung | 2 (67%) | 0 (0%) | |

| AJCC Stage | 0.126 2 | ||

| Early | 12 (60%) | 12 (35%) | |

| Advanced | 5 (25%) | 18 (53%) | |

| Metastasis | 3 (15%) | 4 (12%) |

| Category | Functional Group | Enriched Terms |

|---|---|---|

| GO: Biological Process (BP) | Immune response | Regulation of IL17 production Negative regulation of response to cytokine stimulus Myeloid leukocyte cytokine production |

| Cellular processes | Positive regulation of cell–cell adhesion Regulation of protein secretion Cell activation involved in immune response | |

| GO: Molecular Function (MF) | Receptor binding | Cytokine receptor binding, receptor ligand activity |

| Enzymatic activity | Transferase activity, kinase activity | |

| KEGG Pathway | KEGG pathway | Cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, TNF signaling pathway, NF-kappa B signaling pathway, pathways in cancer, apoptosis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zambrano-Ordoñez, Y.T.; Mejía-Garcia, A.; Ramírez-Mejía, J.M.; Tsao, H.M.; Morales-Suárez, P.D.; Rey-Vargas, L.; Montero-Ovalle, W.J.; Huertas-Caro, C.A.; Lopez-Correa, P.; Riaño-Moreno, J.C.; et al. Comparative Genomic and Microenvironmental Profiles of Hereditary and Sporadic TNBC in Colombian Women. Biology 2025, 14, 1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121706

Zambrano-Ordoñez YT, Mejía-Garcia A, Ramírez-Mejía JM, Tsao HM, Morales-Suárez PD, Rey-Vargas L, Montero-Ovalle WJ, Huertas-Caro CA, Lopez-Correa P, Riaño-Moreno JC, et al. Comparative Genomic and Microenvironmental Profiles of Hereditary and Sporadic TNBC in Colombian Women. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121706

Chicago/Turabian StyleZambrano-Ordoñez, Yina T., Alejandro Mejía-Garcia, Julieta M. Ramírez-Mejía, Hsuan M. Tsao, Paula D. Morales-Suárez, Laura Rey-Vargas, Wendy J. Montero-Ovalle, Carlos A. Huertas-Caro, Patricia Lopez-Correa, Julián C. Riaño-Moreno, and et al. 2025. "Comparative Genomic and Microenvironmental Profiles of Hereditary and Sporadic TNBC in Colombian Women" Biology 14, no. 12: 1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121706

APA StyleZambrano-Ordoñez, Y. T., Mejía-Garcia, A., Ramírez-Mejía, J. M., Tsao, H. M., Morales-Suárez, P. D., Rey-Vargas, L., Montero-Ovalle, W. J., Huertas-Caro, C. A., Lopez-Correa, P., Riaño-Moreno, J. C., Rodriguez, J. L., Sanabria-Salas, M. C., Carvajal-Carmona, L. G., Jordan, I. K., Serrano-Gomez, S. J., Lopez-Kleine, L., & Orozco, C. A. (2025). Comparative Genomic and Microenvironmental Profiles of Hereditary and Sporadic TNBC in Colombian Women. Biology, 14(12), 1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121706