Folate Attenuates Ulcerative Colitis via PI3K/AKT/NF-κB/MLCK Axis Inhibition to Restore Intestinal Barrier Integrity

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Analysis

2.2. Animals

2.3. Establishment of DSS-Induced Experimental Colitis and Folate Administration

2.4. Cell Culture and Stimulation Conditions

2.5. Establishment of Caco-2 Monolayer Model and Barrier Integrity Evaluation

2.6. ELISA

2.7. Colonic MPO Activity Determination

2.8. Histopathological Staining

2.9. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.10. Bulk RNA-Sequencing and qRT-PCR

2.11. Western-Blot

2.12. Immunohistochemical and Immunofluorescence Staining

2.13. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

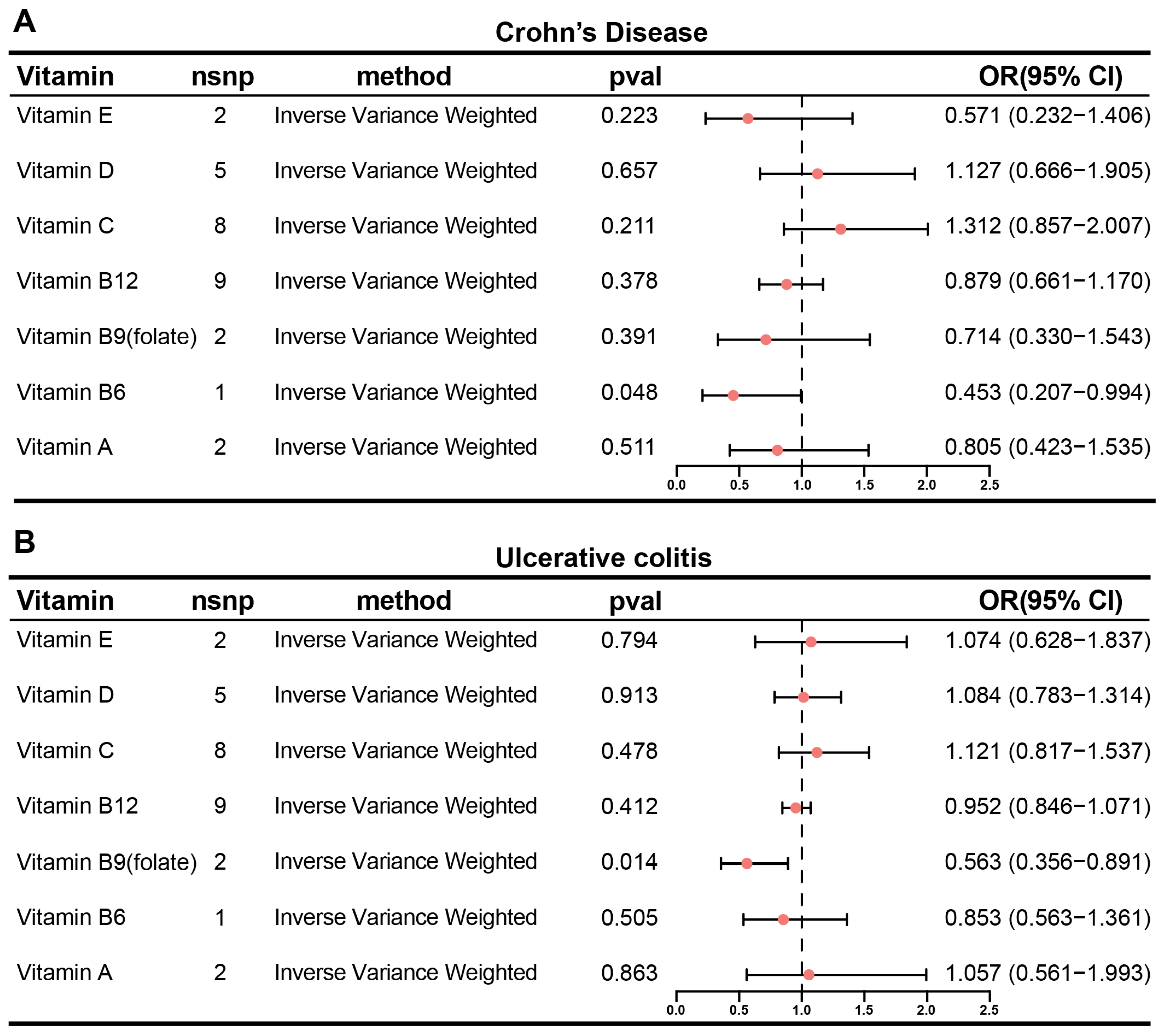

3.1. Inverse Causality Between Circulating Folate and Ulcerative Colitis Risk: A Mendelian Randomization Study

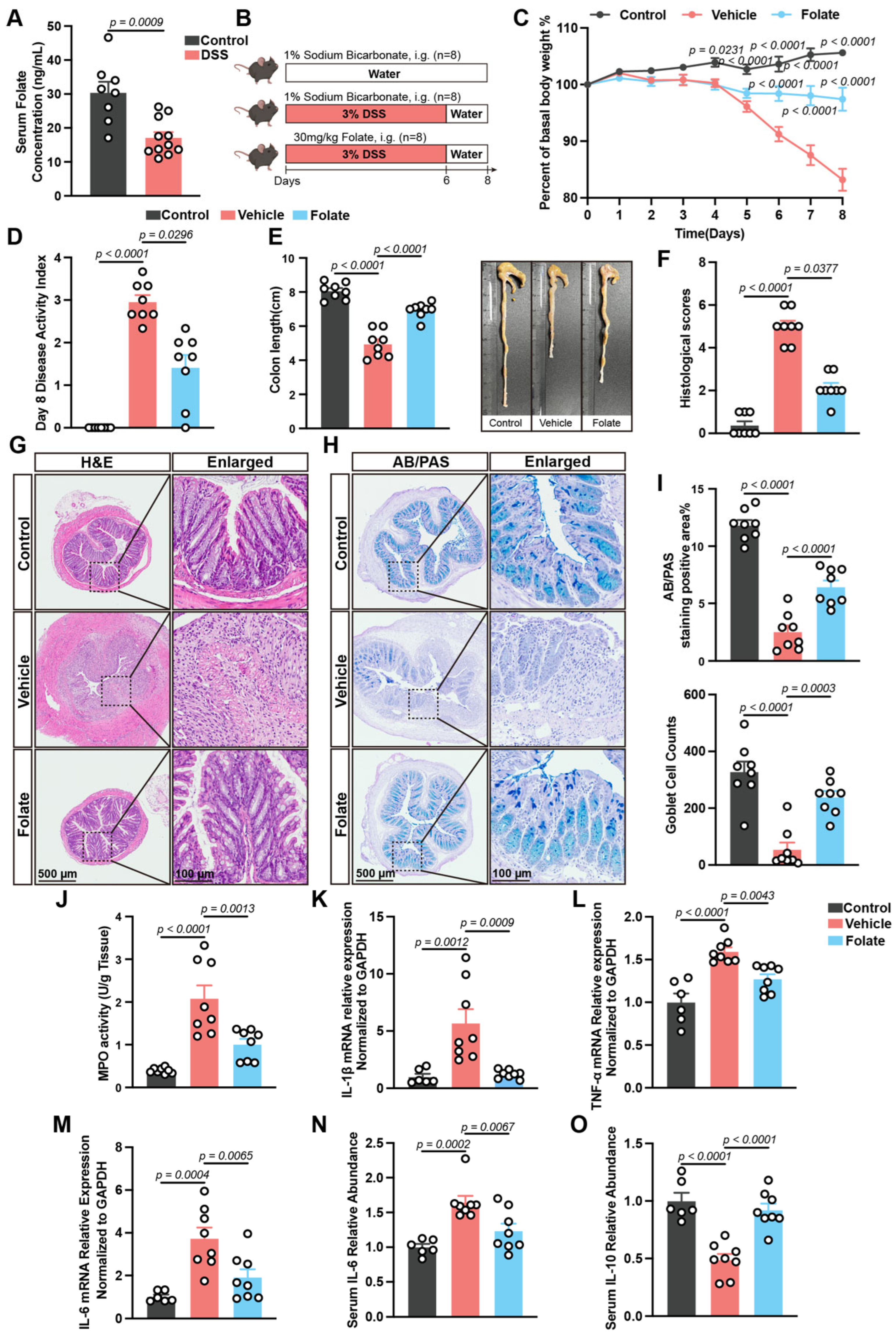

3.2. Folate Supplementation Alleviates DSS-Induced Colitis

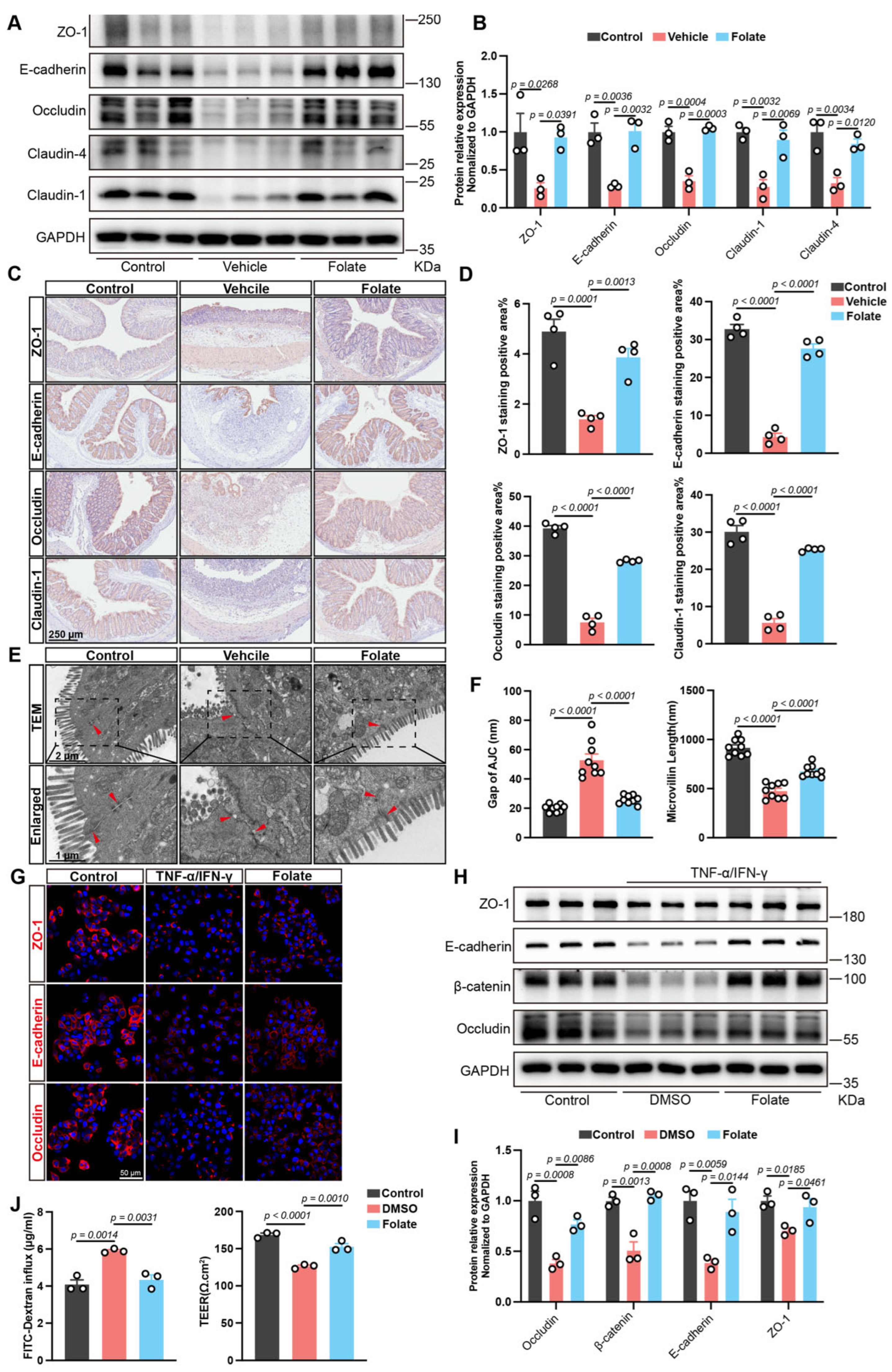

3.3. Folate Restores the Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Both In Vivo and In Vitro

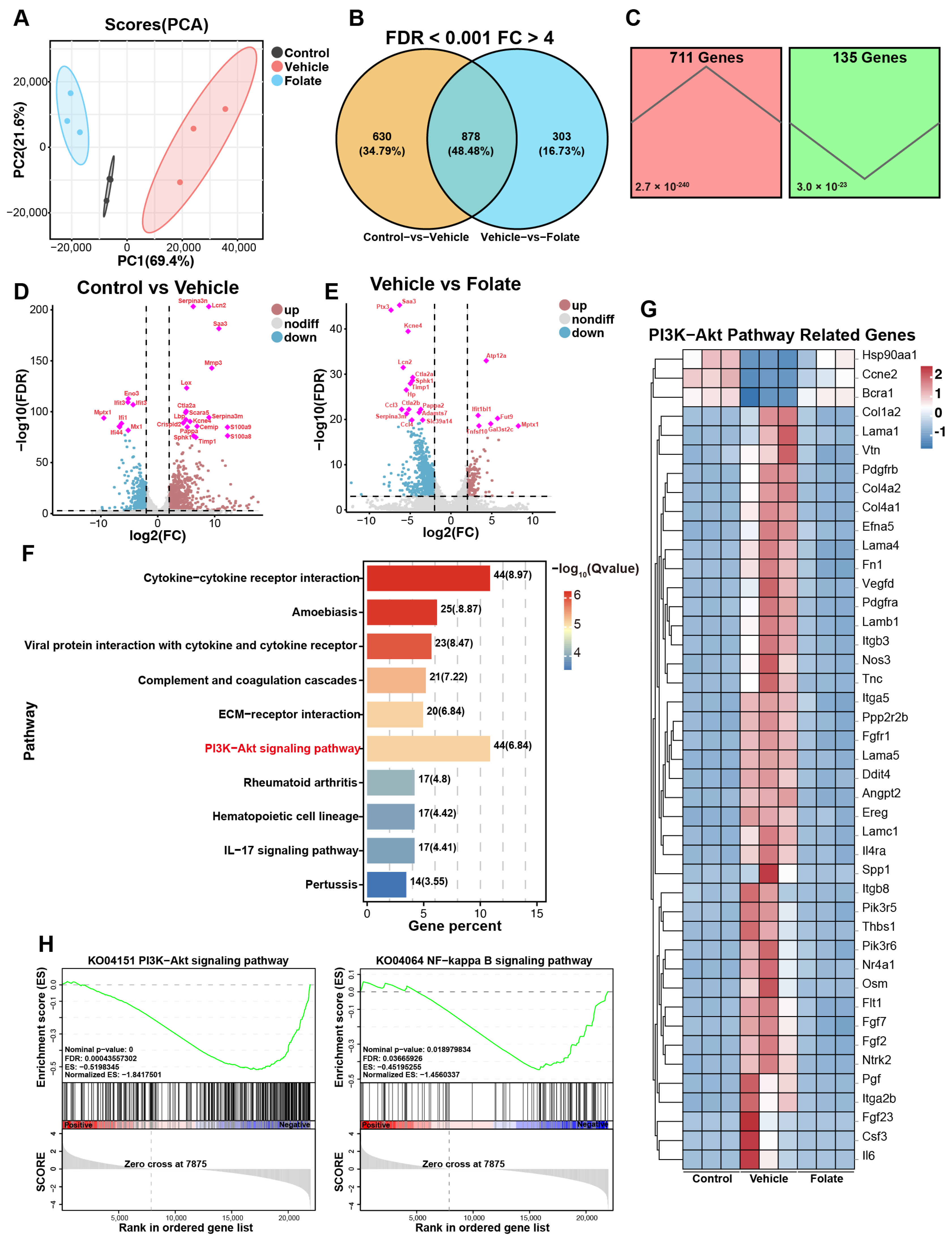

3.4. Folate Reshapes Colonic Transcriptomic Profiles in Colitis Mice

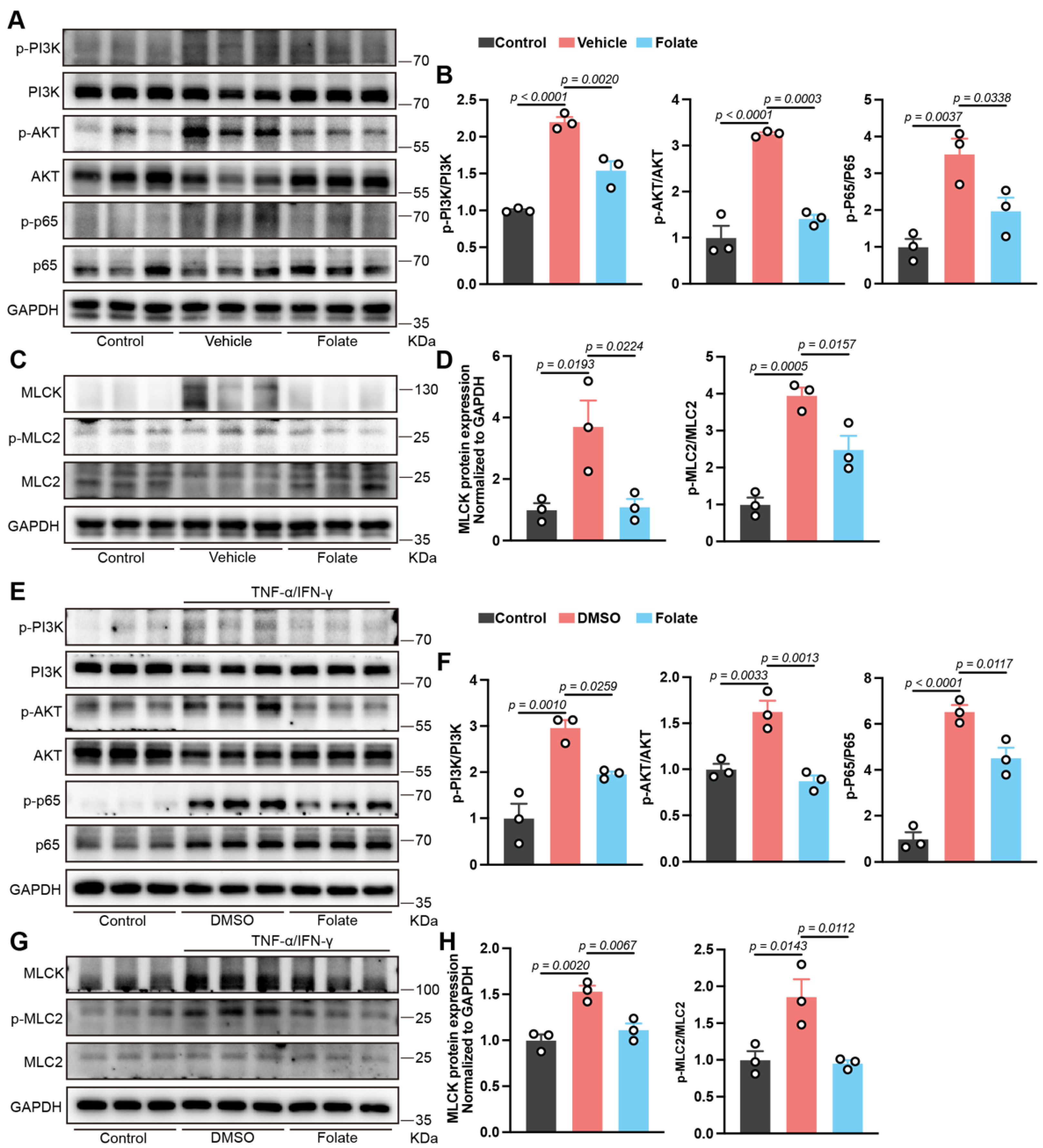

3.5. Involvement of PI3K/AKT/NF-κB Pathway Inhibition in Folate-Mediated Barrier Restoration

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Le Berre, C.; Honap, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2023, 402, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, J.; Mehandru, S.; Colombel, J.-F.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Crohn’s disease. Lancet 2017, 389, 1741–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, G.G. The global burden of IBD: From 2015 to 2025. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, W.Y.; Zhao, M.; Ng, S.C.; Burisch, J. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: East meets west. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 35, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.C.; Shi, H.Y.; Hamidi, N.; Underwood, F.E.; Tang, W.; Benchimol, E.I.; Panaccione, R.; Ghosh, S.; Wu, J.C.Y.; Chan, F.K.L.; et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: A systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2017, 390, 2769–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhang, H.; Xie, S.; Wu, K. Epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: Insights from the past two years. Chin. Med. J. 2025, 138, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khor, B.; Gardet, A.; Xavier, R.J. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2011, 474, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-C.; Stappenbeck, T.S. Genetics and Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Ann. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2016, 11, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East, J.E.; Boyapati, R.K.; Torres, J.; Parker, C.E.; MacDonald, J.K.; Chande, N.; Feagan, B.G. Controversies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Exploring Clinical Dilemmas Using Cochrane Reviews. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 25, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Hibi, T. Improving IBD outcomes in the era of many treatment options. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Chen, Y.; Xie, J.; Cai, W.; Pang, C.; Cui, C.; Huan, Y.; Deng, B. How vitamins act as novel agents for ameliorating diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A comprehensive overview. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 91, 102064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barritt, S.A.; DuBois-Coyne, S.E.; Dibble, C.C. Coenzyme A biosynthesis: Mechanisms of regulation, function and disease. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 1008–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menezo, Y.; Elder, K.; Clement, A.; Clement, P. Folic Acid, Folinic Acid, 5 Methyl TetraHydroFolate Supplementation for Mutations That Affect Epigenesis through the Folate and One-Carbon Cycles. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.C.; Maggini, S. Vitamin C and Immune Function. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlberg, C. Vitamin D and Its Target Genes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolph, T.E.; Meyer, M.; Schwärzler, J.; Mayr, L.; Grabherr, F.; Tilg, H. The metabolic nature of inflammatory bowel diseases. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 753–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolph, T.E.; Meyer, M.; Jukic, A.; Tilg, H. Heavy arch: From inflammatory bowel diseases to metabolic disorders. Gut 2024, 73, 1376–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantos, C.; Aggeletopoulou, I.; Mantzaris, G.J.; Mouzaki, A. Molecular basis of vitamin D action in inflammatory bowel disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2022, 21, 103136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Ma, B.; Xiao, M.; Ren, Q.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, Z. Vitamin D Modified DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice via STING Signaling Pathway. Biology 2025, 14, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Yang, J.; Fan, R.; Song, H.; Zhong, L.; Zeng, T.; Long, R.; Wan, X.; Li, Q.; Liu, L.; et al. Maternal vitamin D regulates the metabolic rearrangement of offspring CD4+ T cells in response to intestinal inflammation. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Q.; Han, C.; Huang, Z.; Chen, S.; Mei, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, K.; et al. Vitamin B5 rewires Th17 cell metabolism via impeding PKM2 nuclear translocation. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Ren, Z.; Liang, W.; Dong, X.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Bhatia, M.; Pan, L.; Sun, J. Thiamine deficiency aggravates experimental colitis in mice by promoting glycolytic reprogramming in macrophages. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 182, 1897–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emdin, C.A.; Khera, A.V.; Kathiresan, S. Mendelian randomization. JAMA 2017, 318, 1925–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekula, P.; Fabiola Del Greco, M.; Pattaro, C.; Köttgen, A. Mendelian Randomization as an Approach to Assess Causality Using Observational Data. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 3253–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ruan, X.; Yuan, S.; Deng, M.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Yu, L.; Satsangi, J.; Larsson, S.C.; Therdoratou, E.; et al. Antioxidants, minerals and vitamins in relation to Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: A Mendelian randomization study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 57, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondul, A.M.; Yu, K.; Wheeler, W.; Zhang, H.; Weinstein, S.J.; Major, J.M.; Cornelis, M.C.; Männistö, S.; Hazra, A.; Hsing, A.W.; et al. Genome-wide association study of circulating retinol levels. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 4724–4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grarup, N.; Sulem, P.; Sandholt, C.H.; Thorleifsson, G.; Ahluwalia, T.S.; Steinthorsdottir, V.; Bjarnason, H.; Gudbjartsson, D.F.; Magnusson, O.T.; Sparsø, T.; et al. Genetic Architecture of Vitamin B12 and Folate Levels Uncovered Applying Deeply Sequenced Large Datasets. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; O’Reilly, P.F.; Aschard, H.; Hsu, Y.-H.; Richards, J.B.; Dupuis, J.; Ingelsson, E.; Karasik, D.; Pilz, S.; Berry, D.; et al. Genome-wide association study in 79,366 European-ancestry individuals informs the genetic architecture of 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Major, J.M.; Yu, K.; Wheeler, W.; Zhang, H.; Cornelis, M.C.; Wright, M.E.; Yeager, M.; Snyder, K.; Weinstein, S.J.; Mondul, A.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies common variants associated with circulating vitamin E levels. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 3876–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Carter, P.; Vithayathil, M.; Kar, S.; Mason, A.M.; Burgess, S.; Larsson, S.C. Genetically predicted circulating B vitamins in relation to digestive system cancers. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 1997–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhou, F.; Xu, H. Circulating vitamin C and D concentrations and risk of dental caries and periodontitis: A Mendelian randomization study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, S.; Popp, V.; Kindermann, M.; Gerlach, K.; Weigmann, B.; Fichtner-Feigl, S.; Neurath, M.F. Chemically induced mouse models of acute and chronic intestinal inflammation. Nat. Protoc. 2017, 12, 1295–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, Q.; Xiong, B.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D. Discoidin domain receptor 1(DDR1) promote intestinal barrier disruption in Ulcerative Colitis through tight junction proteins degradation and epithelium apoptosis. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 183, 106368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; He, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, J.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G.; Shi, T.; Chen, W. Elevated SPARC Disrupts the Intestinal Barrier Integrity in Crohn’s Disease by Interacting with OTUD4 and Activating the MYD88/NF-κB Pathway. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2409419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siatka, T.; Mát’uŠ, M.; Moravcová, M.; Harčárová, P.; Lomozová, Z.; Matoušová, K.; Suwanvecho, C.; Krčmová, L.K.; Mladěnka, P. Biological, dietetic and pharmacological properties of vitamin B9. npj Sci. Food 2025, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, H.; Jabir, M.S.; Liu, X.; Cui, W.; Li, D. Associations between Folate and Vitamin B12 Levels and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2017, 9, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piovani, D.; Danese, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Nikolopoulos, G.K.; Lytras, T.; Bonovas, S. Environmental Risk Factors for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 647–659.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, A.E.; Szymczak-Tomczak, A.; Rychter, A.M.; Zawada, A.; Dobrowolska, A.; Krela-Kaźmierczak, I. Does Folic Acid Protect Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease from Complications? Nutrients 2021, 13, 4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melhem, H.; Hansmannel, F.; Bressenot, A.; Battaglia-Hsu, S.-F.; Billioud, V.; Alberto, J.M.; Gueant, J.L.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Methyl-deficient diet promotes colitis and SIRT1-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress. Gut 2015, 65, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Li, J.; Bing, Y.; Yan, W.; Zhu, Y.; Xia, B.; Chen, M. Diet-Induced Hyperhomocysteinaemia Increases Intestinal Inflammation in an Animal Model of Colitis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2015, 9, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, M.F.; Artis, D.; Becker, C. The intestinal barrier: A pivotal role in health, inflammation, and cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 10, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villablanca, E.J.; Selin, K.; Hedin, C.R.H. Mechanisms of mucosal healing: Treating inflammatory bowel disease without immunosuppression? Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehandru, S.; Colombel, J.-F. The intestinal barrier, an arbitrator turned provocateur in IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, M.F.; Vieth, M. Different levels of healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: Mucosal, histological, transmural, barrier and complete healing. Gut 2023, 72, 2164–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Kuo, W.-T.; Cao, F.; Chanez-Paredes, S.D.; Zeve, D.; Mannam, P.; Jean-François, L.; Day, A.; Graham, W.V.; Sweat, Y.Y.; et al. Tacrolimus-binding protein FKBP8 directs myosin light chain kinase-dependent barrier regulation and is a potential therapeutic target in Crohn’s disease. Gut 2022, 72, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCole, D.F. Finding a mate for MLCK: Improving the potential for therapeutic targeting of gut permeability. Gut 2022, 72, 814–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanauer, S.B. Vitamin D Levels and Outcomes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease–Which is the Chicken and Which is the Egg? Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 15, 247–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Editorial: Vitamin D and IBD: Can We Get Over the “Causation” Hump? Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 111, 720–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund-Nielsen, J.; Vedel-Krogh, S.; Kobylecki, C.J.; Brynskov, J.; Afzal, S.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Vitamin D and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mendelian Randomization Analyses in the Copenhagen Studies and UK Biobank. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 3267–3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, M.; Royce, S.G.; Tikellis, C.; Shallue, C.; Sluka, P.; Wardan, H.; Hosking, P.; Monagle, S.; Thomas, M.; Lubel, J.S.; et al. The intestinal vitamin D receptor in inflammatory bowel disease: Inverse correlation with inflammation but no relationship with circulating vitamin D status. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2019, 12, 1756284818822566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, Y.; Golan, M.A.; Annunziata, M.L.; Du, J.; Dougherty, U.; Kong, J.; Musch, M.; Huang, Y.; Pekow, J.; et al. Intestinal epithelial vitamin D receptor signaling inhibits experimental colitis. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 3983–3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Liu, T.-J.; Shi, Y.-Y.; Zhao, Q. Vitamin D/VDR signaling pathway ameliorates 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis by inhibiting intestinal epithelial apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 35, 1213–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sninsky, J.A.; Sansgiry, S.; Taylor, T.; Perrin, M.; Kanwal, F.; Hou, J.K. The Real-World Impact of Vitamin D Supplementation on Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinical Outcomes. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, M.S.; Stover, P.J. Safety of folic acid. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1414, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruvada, P.; Stover, P.J.; Mason, J.B.; Bailey, R.L.; Davis, C.D.; Field, M.S.; Finnell, R.H.; Garza, C.; Green, R.; Gueant, J.-L.; et al. Knowledge gaps in understanding the metabolic and clinical effects of excess folates/folic acid: A summary, and perspectives, from an NIH workshop. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 1390–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Xu, X.; Mao, C.; Chen, H.; Tang, Y.; Lin, S. Evaluation of In Vivo Folic Acid Bioavailability in Different Mouse Strains Using Enzymatic Digestion Combined with Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 2229–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Cheng, T.; Chen, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, G.; Aa, J. Folate Attenuates Ulcerative Colitis via PI3K/AKT/NF-κB/MLCK Axis Inhibition to Restore Intestinal Barrier Integrity. Biology 2025, 14, 1573. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111573

Zhang S, Cheng T, Chen Y, Wang M, Wang G, Aa J. Folate Attenuates Ulcerative Colitis via PI3K/AKT/NF-κB/MLCK Axis Inhibition to Restore Intestinal Barrier Integrity. Biology. 2025; 14(11):1573. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111573

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shize, Tian Cheng, Yuang Chen, Mengqin Wang, Guangji Wang, and Jiye Aa. 2025. "Folate Attenuates Ulcerative Colitis via PI3K/AKT/NF-κB/MLCK Axis Inhibition to Restore Intestinal Barrier Integrity" Biology 14, no. 11: 1573. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111573

APA StyleZhang, S., Cheng, T., Chen, Y., Wang, M., Wang, G., & Aa, J. (2025). Folate Attenuates Ulcerative Colitis via PI3K/AKT/NF-κB/MLCK Axis Inhibition to Restore Intestinal Barrier Integrity. Biology, 14(11), 1573. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111573