Uncovering Forensic Taphonomic Agents: Animal Scavenging in the European Context

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Implications of Vertebrate Scavenging

3. Forensically Important Vertebrate Scavengers in Mainland Europe and the UK

3.1. Felids (Order Carnivora, Family Felidae)

3.2. Canids (Order: Carnivora, Family: Canidae)

3.3. Ursids (Order: Carnivora, Family: Ursidae)

3.4. Mustelids (Order: Carnivora, Family: Mustelinae)

3.5. Procyonids (Order: Carnivora, Family: Procyonidae)

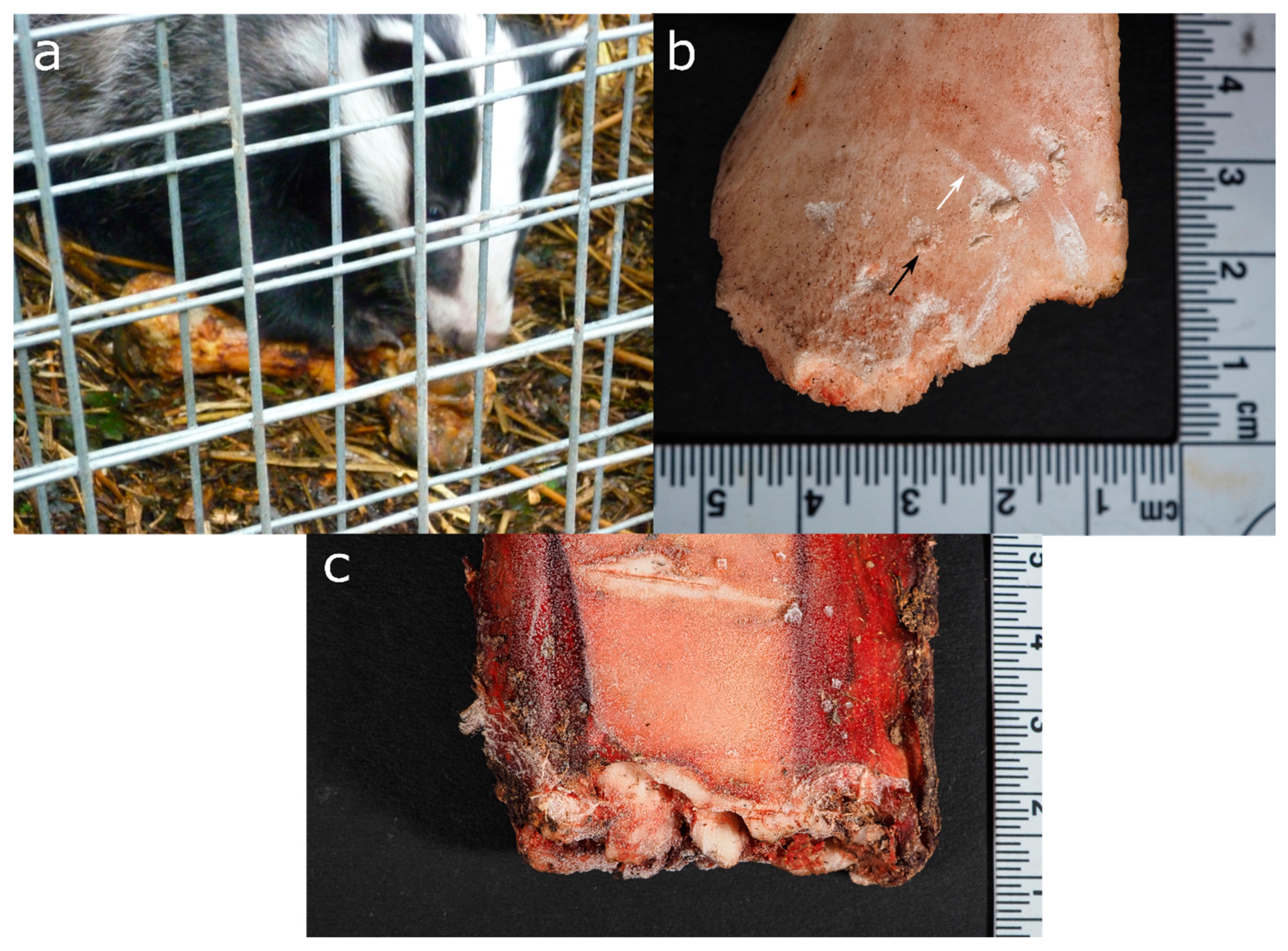

3.6. Suids (Order: Artiodactyla, Family: Suidae)

3.7. Rodents (Order: Rodentia)

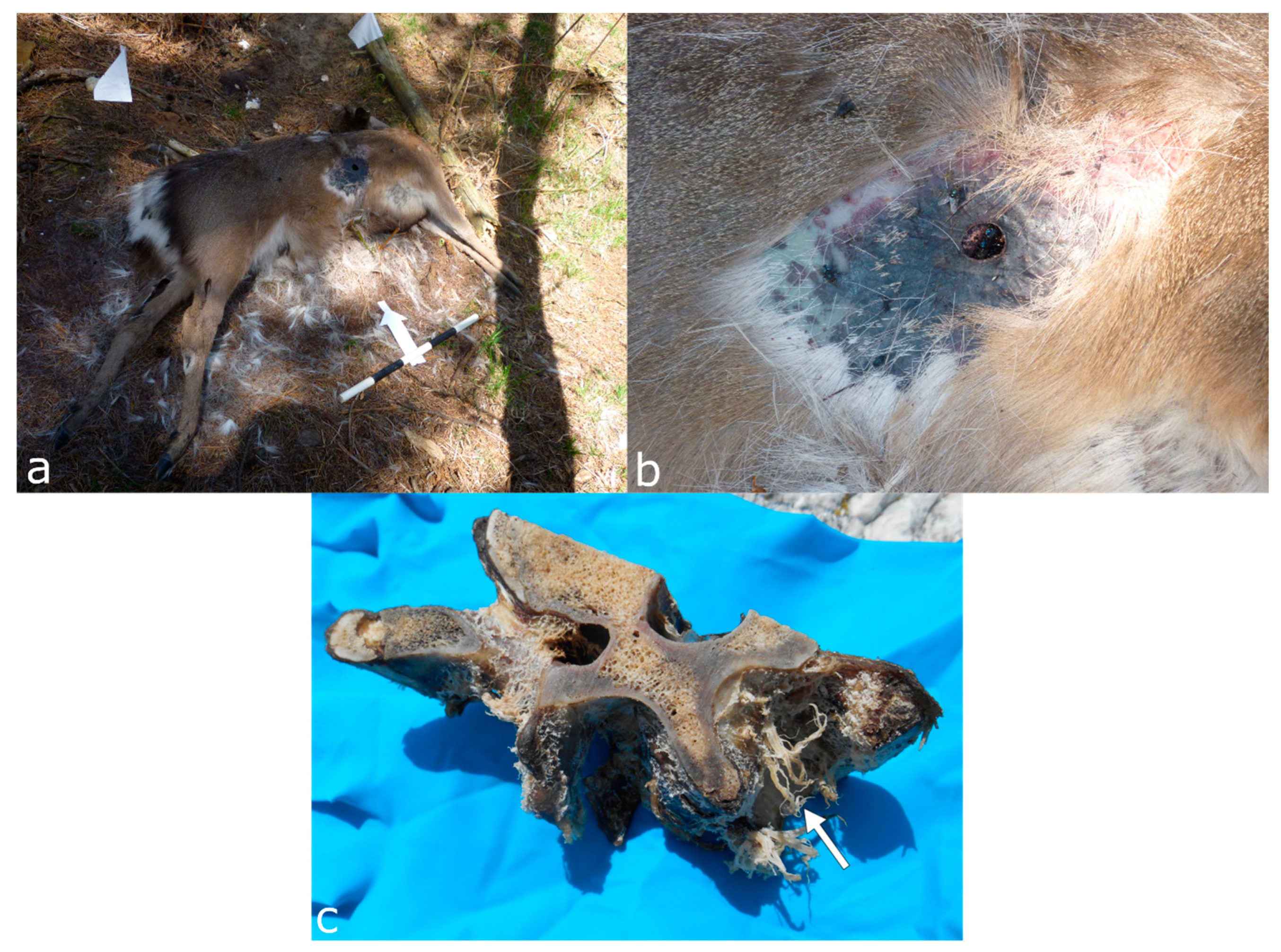

3.8. Cervids and Bovids (Order: Artiodactyla, Family: Cervidae, Bovidae)

3.9. Birds (Class: Aves)

4. Discussion

- Location and pattern of lesions. Animal scavenging can result in species-typical damage to the skeleton. Observed damage to human remains from forensic casework can be compared to published damage patterns.

- Lesion morphology. The manifestations of trauma caused by sharp force are well described in the literature [171]. Additionally, for many animal species, there are reports on typical lesions, such as the tooth marks of carnivores [54,55,99,112] and rodents [35,49] that are not usually confused with trauma. However, tooth marks may be concentrated in areas consumed or removed from the scene by the scavengers, and in the absence of tooth marks, it is difficult to attribute non-specific force impacts such as fractures to either trauma or scavenging [168]. In forensic casework, it is important to observe as many skeletal elements as possible as well as to include environmental factors in the analysis. Observations will then be compared with known and reported causes.

- Lesion surrounding. The immediate surrounding of a lesion can provide information about the processes that caused the damage. For instance, if long bone epiphyses are broken off, a scavenger cause is more likely than a traumatic cause if there are “gouged out” shaft ends, pits and punctures, and smoothing of the lesion edges due to extensive animal licking [49,59,99].

- Lack of vital reactions. No haemorrhaging at a wound indicates a postmortem cause, which is by definition the case with scavenging. On weathered bones, taphonomically induced lesions are often lighter in colour than the surrounding bone [168]. However, perpetrators can also carry out postmortem mutilations, often involving dismemberment of the body or concealment of identity.

- Direct evidence of scavengers. Sometimes, vertebrate scavengers are observed on the corpse itself or nearby, which makes them a likely or even certain scavenger of the remains [172]. It is further possible to install camera traps at the site to capture returning vertebrates, even after the remains are removed.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Read, J.L.; Wilson, D. Scavengers and Detritivores of Kangaroo Harvest Offcuts in Arid Australia. Wildl. Res. 2004, 31, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R.C.; Forbes, S.L.; Meyer, J.; Dadour, I. Forensically Significant Scavenging Guilds in the Southwest of Western Australia. Forensic Sci. Int. 2010, 198, 85–91. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20171028 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, R.C.; Forbes, S.L.; Meyer, J.; Dadour, I.R. A Preliminary Investigation into the Scavenging Activity on Pig Carcasses in Western Australia. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2007, 3, 194–199. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25869163 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Steadman, D.W.; Dautartas, A.; Kenyhercz, M.W.; Jantz, L.M.; Mundorff, A.; Vidoli, G.M. Differential Scavenging among Pig, Rabbit, and Human Subjects. J. Forensic Sci. 2018, 63, 1684–1691. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29649349 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willey, P.L.; Snyder, M. Canid modification of human remains—Implications for time-since-death estimations. J. Forensic Sci. 1989, 34, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubelaker, D.H. Taphonomic applications in forensic anthropology. In Forensic Taphonomy: The Postmortem Fate of Human Remains; Sorg, M.H., Haglund, W.D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997; pp. 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sincerbox, S.N.; DiGangi, E. Forensic Taphonomy and Ecology of North American Scavengers; Academic Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, W.C. Decomposition of buried and submerged bodies. In Forensic Taphonomy: The Postmortem Fate of Human Remains; Sorg, M.H., Haglund, W.D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997; pp. 459–468. [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocki, S.P. Forensic taphonomy. In Handbook of Forensic Anthropology and Archaeology; Blau, S., Ubelaker, D.H., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Komar, D.A. Twenty-Seven Years of Forensic Anthropology Casework in New Mexico. J. Forensic Sci. 2003, 48, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Stillman, R.; Smith, M.J.; Korstjens, A.H. Scavenging in Northwestern Europe: A Survey of UK Police Specialist Search Officers. Policing 2014, 8, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indra, L.; Lösch, S. Forensic Anthropology Casework from Switzerland (Bern): Taphonomic Implications for the Future. Forensic Sci. Int. Rep. 2021, 4, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubelaker, D.H.; DeGaglia, C.M. The Impact of Scavenging: Perspective from Casework in Forensic Anthropology. Forensic Sci. Res. 2020, 5, 32–37. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32490308 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Woollen, K.; Byrnes, J.F. A Retrospective Analysis of Scavenging in Southern Nevada Forensic Anthropology Cases (2000–2021). In Proceedings of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences 74th Annual Scientific Conference, Seattle, WA, USA, 8 February 2022; Volume XXVIII, pp. 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenschine, R.J. Carcass consumption sequences and the archaeological distinction of scavenging and hunting. J. Hum. Evol. 1976, 15, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Rodrigo, M. Flesh availability and bone modifications in carcasses consumed by lions. PALAEO 1999, 149, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Rodrigo, M.; Gidna, A.O.; Yravedra, J.; Musiba, C. A comparative neo-taphonomic study of felids, hyaenids and canids—An analogical framework based on long bone modification patterns. J. Taphon. 2012, 10, 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, J.A.; Plummer, T.; Hartstone-Rose, A. Characterizing Felid Tooth Marking and Gross Bone Damage Patterns Using gis Image Analysis: An Experimental Feeding Study with Large Felids. J. Hum. Evol. 2015, 80, 114–134. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25467112 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotan, E. Feeding the Scavengers. Actualistic Taphonomy in the Jordan Valley, Israel. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2000, 10, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, N.M. Taphonomic Effects of Vulture Scavenging. J. Forensic Sci. 2009, 54, 523–528. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19432736 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spradley, M.K.; Hamilton, M.D.; Giordano, A. Spatial Patterning of Vulture Scavenged Human Remains. Forensic Sci. Int. 2012, 219, 57–63. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22204892 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Dabbs, G.R.; Martin, D.C. Geographic Variation in the Taphonomic Effect of Vulture Scavenging: The Case for Southern Illinois. J. Forensic Sci. 2013, 58, S20–S25. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23181511 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- McPhee, M.E.; Carlstead, K. The importance of maintaining natural behaviors in captive mammals. In Wild Mammals in Captivity: Principles and Techniques for Zoo Management; Kleiman, D.G., Thompson, K.V., Baer, C.K., Eds.; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010; pp. 303–313. [Google Scholar]

- Young, A.; Stillman, R.; Smith, M.J.; Korstjens, A. An Experimental Study of Vertebrate Scavenging Behavior in a Northwest European Woodland Context. J. Forensic Sci. 2014, 59, 1333–1342. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24611615 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Komar, D.; Beattie, O. Identifying bird scavenging in fleshed and dry remains. Can. Soc. Forensic Sci. J. 1998, 31, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüner, E.A.; Peter, J.F.B. In Situ Caching of a Large Mammal Carcass by a Fisher, Martes Pennanti. Can. Field-Nat. 2012, 126, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, M.A.; Schneider, V. On the temporal onset of postmortem animal scavenging. “Motivation”-of the animal. Forensic Sci. Int. 1997, 89, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byard, R.W.; James, R.A.; Gilbert, J.D. Diagnostic problems associated with cadaveric trauma from animal activity. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2002, 23, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buschmann, C.; Solarino, B.; Püschel, K.; Czubaiko, F.; Heinze, S.; Tsokos, M. Post-mortem decapitation by domestic dogs: Three case reports and review of the literature. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2011, 7, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsokos, M.; Byard, R.W.; Puschel, K. Extensive and Mutilating Craniofacial Trauma Involving Defleshing and Decapitation: Unusual Features of Fatal Dog Attacks in the Young. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2007, 28, 131–136. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17525563 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puskas, C.M.; Rumney, D.T. Bilateral fractures of the coronoid processes. Differential diagnosis of intra-oral gunshot trauma and scavenging using a sheep crania model. J. Forensic Sci. 2003, 48, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symes, S.A.; Williams, J.A.; Murray, E.A.; Hoffman, J.M.; Holland, T.D.; Saul, J.M.; Saul, F.P.; Pope, E.J. Taphonomic context of sharp-force trauma in suspected cases of human mutilation and dismemberment. In Advances in Forensic Taphonomy: Method, Theory, and Archaeological Perspectives; Sorg, M.H., Haglund, W.D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; pp. 404–434. [Google Scholar]

- Rippley, A.; Larison, N.C.; Moss, K.E.; Kelly, J.D.; Bytheway, J.A. Scavenging Behavior of Lynx Rufus on Human Remains during the Winter Months of Southeast Texas. J. Forensic Sci. 2012, 57, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, F. Artefact in forensic medicine—Postmortem rodent activity. J. Forensic Sci. 1994, 39, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haglund, W.D. Contribution of rodents to postmortem artifacts of bone and soft tissue. J. Forensic Sci. 1992, 37, 1459–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahlow, J.A.; Linch, C.A. A baby, a virus, and a rat. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2000, 21, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, R.W.; Bass, W.M.; Meadows, L. Time since death and decomposition of the human body. Variables and observations in case and experimental field studies. J. Forensic Sci. 1990, 35, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, M.J.; Anderson, G.S. Time since death: A review of the current status of methods used in the later postmortem interval. Can. Soc. Forensic Sci. J. 2001, 34, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suckling, J.K.; Spradley, M.K.; Godde, K. A Longitudinal Study on Human Outdoor Decomposition in Central Texas. J. Forensic Sci. 2016, 61, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galloway, A. The Process of Decomposition: A Model from the Arizona Sonoran Desert. In Forensic Taphonomy: The Postmortem Fate of Human Remains; Sorg, M.H., Haglund, W.D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997; pp. 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Sorg, M.H.; Dearborn, J.H.; Monahan, E.I.; Ryan, H.F.; Sweeney, K.G.; David, E. Forensic Taphonomy in Marine Contexts. In Forensic Taphonomy: The Postmortem Fate of Human Remains; Sorg, M.H., Haglund, W.D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997; pp. 567–604. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, S.B.; Harrison, K.; Errickson, D.; Márquez-Grant, N. The Effect of Seasonality on the Application of Accumulated Degree-Days to Estimate the Early Post-Mortem Interval. Forensic Sci. Int. 2020, 315, 110419. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32784040 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, W.M. Outdoor Decomposition Rates in Tennessee. In Forensic Taphonomy: The Postmortem Fait of Human Remains; Sorg, M.H., Haglund, W.D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997; pp. 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, L.E.; Anderson, G.S. Forensic Entomology: A Database of Insect Succession on Carrion in Northern and Interior BC; Technical Report TR-04-96; Canadian Police Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Synstelien, J.A. Studies in Taphonomy: Bone and Soft Tissue Modifications by Postmortem Scavengers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Klippel, W.E.; Synstelien, J.A. Rodents as Taphonomic Agents: Bone Gnawing by Brown Rats and Gray Squirrels. J. Forensic Sci. 2007, 52, 765–773. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17524050 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanLaerhoven, S.L.; Hughes, C. Testing different search methods for recovering scattered and scavenged remains. Can. Soc. Forensic Sci. J. 2008, 41, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjorlien, Y.P.; Beattie, O.B.; Peterson, A.E. Scavenging activity can produce predictable patterns in surface skeletal remains scattering: Observations and comments from two experiments. Forensic Sci. Int. 2009, 188, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokines, J.T. Faunal Dispersal, Reconcentration, and Gnawing Damage to Bone in Terrestrial Environments. In Manual of Forensic Taphonomy; Pokines, J.T., Symes, S.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 201–248. [Google Scholar]

- Komar, D.A.; Potter, W.E. Percentage of body recovered and its effect on identification rates and cause and manner of death determination. J. Forensic Sci. 2007, 52, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Stillman, R.; Smith, M.J.; Korstjens, A.H. Applying Knowledge of Species-Typical Scavenging Behavior to the Search and Recovery of Mammalian Skeletal Remains. J. Forensic Sci. 2016, 61, 458–466. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26551615 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, J.A.; Plummer, T.W.; Bose, R. A gis-based approach to documenting large canid damage to bones. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2014, 409, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coard, R. Ascertaining an agent: Using tooth pit data to determine the carnivore/s responsible for predation in cases of suspected big cat kills in an upland area of britain. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2007, 34, 1677–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney-Rivera, C.; Plummer, T.W.; Hodgson, J.A.; Forrest, F.; Hertel, F.; Oliver, J.S. Pits and pitfalls: Taxonomic variability and patterning in tooth mark dimensions. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 2597–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, M.; Gidna, A.O.; Yravedra, J.; Domínguez-Rodrigo, M. A study of dimensional differences of tooth marks (pits and scores) on bones modified by small and large carnivores. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2012, 4, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Stillman, R.; Smith, M.J.; Korstjens, A.H. Scavenger Species-Typical Alteration to Bone: Using Bite Mark Dimensions to Identify Scavengers. J. Forensic Sci. 2015, 60, 1426–1435. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26249734 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokines, J.T. Taphonomic alterations by the rodent species woodland vole (microtus pinetorum) upon human skeletal remains. Forensic Sci. Int. 2015, 257, e16–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, I.; Schneider, P.M.; Olek, K.; Rothschild, M.A.; Tsokos, M. Examination of postmortem animal interference to human remains using cross-species multiplex pcr. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2006, 2, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binford, L.R. Bones Ancient Men and Modern Myths; Academic Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Bryant, K.A.; Haskard, K.; Major, T.; Bruce, S.; Calver, M.C. Factors determining the home ranges of pet cats: A meta-analysis. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 203, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natural Biodiversity Network (NBN). NBN Atlas; NBN Atlas Partnership. 2021. Available online: https://nbnatlas.org/ (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Kleiman, D.G.; Geist, V.; McDade, M.C. Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia; Mammals iii; Gale Group: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2004; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, L.H. Tracks and Signs of the Animals and Birds of Britain and Europe; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ragg, J.R.; Mackintosh, C.G.; Moller, H. The Scavenging Behaviour of Ferrets (mustela furo), Feral Cats (felis domesticus), Possums (trichosurus vulpecula), Hedgehogs (erinaceus europaeus) and Harrier Hawks (circus approximans) on Pastoral Farmland in New Zealand: Implications for Bovine Tuberculosis Transmission. N. Z. Vet. J. 2000, 48, 166–175. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16032148 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.L.; Shahrom, A.W.; Chapman, R.C.; Vanezis, P. Postmortem injuries by indoor pets. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 1994, 15, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntirukpong, A.; Mann, R.W.; DeFreytas, J.R. Postmortem scavenging of human remains by domestic cats. Siriraj Med. J. 2017, 69, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.; Smith, A.; Baigent, C.; Connor, M. The Scavenging Patterns of Feral Cats on Human Remains in an Outdoor Setting. J. Forensic Sci. 2020, 65, 948–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byard, R.W. Postmortem Predation by a Clowder of Domestic Cats. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2020, 17, 144–147. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32889630 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperhake, J.P.; Tsokos, M. Postmortem animal depredation by a domestic cat. Arch. Kriminol. 2001, 208, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prahlow, J.A.; Byard, R.W. Atlas of Forensic Pathology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Byard, R.W. An Unusual Pattern of Post-Mortem Injury Caused by Australian Fresh Water Yabbies (cherax destructor). Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2020, 16, 373–376. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32026383 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, J.W.; Logan, K.A.; Sweanor, L.L.; Boyce, W.M.; Jones, C.A. Scavenging behavior in puma. Southwest. Nat. 2005, 50, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Wall, S.B. Food Hoarding in Animals; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff-Mattson, Z.; Mattson, D. Effects of simulated mountain lion caching on decomposition of ungulate carcasses. West. N. Am. Nat. 2009, 69, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moran, N.C.; O’Connor, T.P. Bones that cats gnawed upon. Circaea 1991, 9, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, M.C.; Kaufmann, C.A.; Massigoge, A.; Gutiérrez, M.A.; Rafuse, D.J.; Scheifler, N.A.; González, M.E. Bone Modification and Destruction Patterns of Leporid Carcasses by Geoffroy’s Cat (Leopardus Geoffroyi): An Experimental Study. Quat. Int. 2012, 278, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.M.; Berg, M.J.; Tolhurst, B.A.; Chauvenet, A.L.; Smith, G.C.; Neaves, K.; Lochhead, J.; Baker, P.J. Changes in the Distribution of Red Foxes (Vulpes Vulpes) in Urban Areas in Great Britain: Findings and Limitations of a 134 Media-Driven Nationwide Survey. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostecke, R.M.; Linz, G.M.; Bleier, W.J. Survival of avian carcasses and photographic evidence of predators and scavengers. J. Field Ornithol. 2001, 72, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vault, T.L.; Rhodes, O.E. Identification of vertebrate scavengers of small mammal carcasses in a forested landscape. Acta Theriol. 2002, 47, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selva, N.; Jędrzejewska, B.; Jędrzejewski, W.; Wajrak, A. Factors Affecting Carcass Use by a Guild of Scavengers in European Temperate Woodland. Can. J. Zool. 2005, 83, 1590–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junod, C.A. Subaerial Bone Weathering and other Taphonomic Changes in a Temperate Climate. Master’s Thesis, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, Z.H.; Beasley, J.C.; Rhodes, O.E., Jr. Carcass Type Affects Local Scavenger Guilds More than Habitat Connectivity. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147798. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26886299 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumann, M.; Nolte, I.; Huckenbeck, W.; Barz, J. Tierfrass—Wenige stunden nach todeseintritt. Rechtsmedizin 1996, 7, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsokos, M.; Schultz, F. Indoor postmortem animal interference by carnivores and rodents—Report of two cases and review of the literature. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1999, 112, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romain, N.; Brandt-Casadevall, C.; Dimo-Simonin, K.M.; Mangin, P.; Papilloud, J. Post-mortem castration by a dog—A case report. Med. Sci. Law 2002, 42, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, D.W.; Worne, H. Canine Scavenging of Human Remains in an Indoor Setting. Forensic Sci. Int. 2007, 173, 78–82. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17210237 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Verzeletti, A.; Cortellini, V.; Vassalini, M. Post-Mortem Injuries by a Dog: A Case Report. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2010, 17, 216–219. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20382359 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Colard, T.; Delannoy, Y.; Naji, S.; Gosset, D.; Hartnett, K.; Becart, A. Specific Patterns of Canine Scavenging in Indoor Settings. J. Forensic Sci. 2015, 60, 495–500. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25677199 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Carrasco, M.; Pisani, J.M.A.; Scarso-Giaconi, F.; Fonseca, G.M. Indoor postmortem mutilation by dogs: Confusion, contradictions, and needs from the perspective of the forensic veterinarian medicine. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 15, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewson, R.; Kolb, H.H. Scavenging on sheep carcases by foxes (vulpes vulpes) and badgers (meles meles). Notes Mammal Soc. 1976, 33, 496–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczensky, P.; Hayes, R.D.; Promberger, C. Effect of raven corvus corax scavenging on the kill rates of wolf canis lupus packs. Wildl. Biol. 2005, 11, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, E.H. Disarticulation of kangaroo skeletons in semi-arid Australia. Aust. J. Zool. 2001, 49, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, R.J.; Lord, W.D. Taphonomy of Child-Sized Remains: A study of Scattering and Scavenging in Virginia, USA. J. Forensic Sci. 2006, 51, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, O.J.F.; Field, J.; Letnic, M. Variation in the taphonomic effect of scavengers in semi-arid Australia linked to rainfall and the el niño southern oscillation. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2006, 16, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haglund, W.D.; Reay, D.T.; Swindler, D.R. Canid Scavenging Disarticulation Sequence of Human Remains in the Pacific Northwest. J. Forensic Sci. 1989, 34, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Marquez-Grant, N.; Stillman, R.; Smith, M.J.; Korstjens, A.H. An Investigation of Red Fox (vulpes vulpes) and Eurasian Badger (meles meles) Scavenging, Scattering, and Removal of Deer Remains: Forensic Implications and Applications. J. Forensic Sci. 2014, 60 (Suppl. 1), S39–S55. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25065997 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Gadbois, S.; Sievert, O.; Reeve, C.; Harrington, F.H.; Fentress, J.C. Revisiting the Concept of Behavior Patterns in Animal Behavior with an Example from Food-Caching Sequences in Wolves (canis lupus), Coyotes (canis latrans), and Red Foxes (vulpes vulpes). Behav. Process. 2015, 110, 3–14. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25446624 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, A.C.; Gotthardt, R.M. Predator and scavenger modification of recent equid skeletal assemblages (wolves). ARCTIC 1984, 37, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Haglund, W.D.; Reay, D.T.; Swindler, D.R. Tooth mark artifacts and survival of bones in animal scavenged human skeletons. J. Forensic Sci. 1988, 33, 985–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokines, J. A procedure for processing outdoor surface forensic scenes yielding skeletal remains among leaf litter. J. Forensic Identif. 2015, 65, 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Mech, L.D.; Boitani, L. Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- De Munnynck, K.; van de Voorde, W. Forensic Approach of Fatal Dog Attacks: A Case Report and Literature Review. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2002, 116, 295–300. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12376842 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, G. Evidence of carnivore gnawing on pleistocene and recent mammalian bones. Pelobiology 1980, 6, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, G. A guide for differentiating mammalian carnivore taxa responsible for gnaw damage to herbivore limb bones. Paleobiology 1983, 9, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, T.R. Carnivore voiding—A taphonomic process with the potential for the deposition of forensic evidence. J. Forensic Sci. 2001, 46, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Nadal, M.; Cáceres, I.; Fosse, P. Characterization of a Current Coprogenic Sample Originated by Canis Lupus as a Tool for Identifying a Taphonomic Agent. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2010, 37, 2959–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, L.N. Taphonomic Signatures of Animal Scavenging in Northern California—A Forensic Anthropological Analysis. Master’s Thesis, California State University, Long Beach, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sala, N.; Arsuaga, J.L. Taphonomic Studies with Wild Brown Bears (Ursus Arctos) in the Mountains of Northern Spain. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 1389–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgmork, K. Caching behaviour of brown bears. J. Mammal. 1982, 63, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladié, P.; Huguet, R.; Diez, C.; Rodriguez-Hidalgo, A.; Carbonell, E. Taphonomic modifications produced by modern brown bears (ursus arctos). Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2013, 23, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, E.A.; Stefan, H.V.; Powell, J.F. Skeletal manifestations of bear scavenging. J. Forensic Sci. 2000, 45, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udoni, M. A Taphonomic Study of Black Bear (Ursus Americanus) and Grizzly Bear (u. Arctos) Tooth Marks on Bone. Master’s Thesis, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, R.A. Resource partitioning among British and Irish mustelids. J. Anim. Ecol. 2002, 71, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Mill, P.J. Cranial Variation in British Mustelids. J. Morphol. 2004, 260, 57–64. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15052596 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryšavá-Nováková, M.; Koubek, P. Feeding habits of two sympatric mustelid species, European polecat and stone marten in the Czech Republic. Folia Zool. 2009, 58, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hobischak, N.R. Freshwater Invertebrate Succession and Decompositional Studies on Carrion in British Columbia. Master’s Thesis, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- King, K.A.; Lord, W.D.; Ketchum, H.R.; O’Brien, R.C. Postmortem Scavenging by the Virginia Opossum (didelphis virginiana): Impact on Taphonomic Assemblages and Progression. Forensic Sci. Int. 2016, 266, 576.e1–576.e6. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27430919 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokines, J.; Pollock, C. The Small Scavenger Guild of Massachusetts. Forensic Anthropol. 2018, 1, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonnel, N.; Anderson, G. Aquatic Forensics: Determination of Time since Submergence Using Aquatic Invertebrates; Canadian Police Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kruuk, H. Spatial Organization and Territorial Behaviour of the European Badger (Meles Meles). J. Zool. 1978, 184, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A. The effects of terrestrial mammalian scavenging and avian scavenging on the body. In Taphonomy of Human Remains: Forensic Analysis of the Dead and the Depositional Environment; Schotsmans, E.M.J., Márquez-Grant, N., Forbes, S.L., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 2017; pp. 212–234. [Google Scholar]

- Wroe, S.; McHenry, C.; Thomason, J. Bite club—Comparative bite force in big biting mammals and the prediction of predatory behaviour in fossil taxa. Biol. Sci. 2005, 272, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Jantz, L.M.; Smith, J. Investigation into Seasonal Scavenging Patterns of Raccoons on Human Decomposition. J. Forensic Sci. 2016, 61, 467–471. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27404620 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hannigan, A. A Descriptive Study of Forensic Implications of Raccoon Scavenging in Maine; University of Maine: Maine, ME, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Berryman, H.E. Disarticulation pattern and tooth mark artifacts associated with pig scavenging of human remains: A case study. In Advances in Forensic Taphonomy: Method, Theory, and Archaeological Perspectives; Sorg, M.H., Haglund, W.D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; pp. 487–495. [Google Scholar]

- De Vault, T.L.; Brisbin, J.I.L.; Rhodes, J.O.E. Factors influencing the acquisition of rodent carrion by vertebrate scavengers and decomposers. Can. J. Zool. 2004, 82, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiman, D.G.; Geist, V.; McDade, M.C. Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia; Mammals, I.V., Ed.; Gale Group: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2004; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Tucak, Z. Ergebnisse von 155 mageninhaltsuntersuchungen von schwarzwild (sus scrofa l.) im ungegatterten teil des waldjagdrevieres belje in Baranja. Z. Jagdwiss. 1996, 42, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, H.J. Bone Consumption by Pigs in a Contemporary Serbian Village. J. Field Rchaeol. 1988, 15, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Solera, S.D.; Domínguez-Rodrigo, M. A taphonomic study of bone modification and of tooth-mark patterns on long limb bone portions by suids. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2009, 19, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropohl, D.; Scheithauer, R.; Pollak, S. Postmortem injuries inflicted by domestic golden hamster—Morphological aspects and evidence by DNA typing. Forensic Sci. Int. 1995, 72, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkol, Z.; Hösükler, E. Postmortem animal attacks on human corpses. In Post Mortem Examination and Autopsy—Current Issues from Death to Laboratory Analysis; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bumann, G.B.; Stauffer, D.F. Scavenging of Ruffed Grouse in the Appalachians Influences and Implications. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2002, 30, 853–860. [Google Scholar]

- Pokines, J.T.; Sussman, R.; Gough, M.; Ralston, C.; McLeod, E.; Brun, K.; Kearns, A.; Moore, T.L. Taphonomic Analysis of Rodentia and Lagomorpha Bone Gnawing Based upon Incisor Size. J. Forensic Sci. 2017, 62, 50–66. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27859293 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Haglund, W.D. Rodents and human remains. In Forensic Taphonomy: The Postmortem Fate of Human Remains; Sorg, M.H., Haglund, W.D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997; pp. 405–414. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, C.A.; Myburgh, J.; Brits, D. Scavenger activity in a peri-urban agricultural setting in the highveld of South Africa. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2020, 135, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, A.J. Similarity of bones and antlers gnawed by deer to human artefacts. Nature 1973, 246, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierdorf, U. A further example of long-bone damage due to chewing by deer. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 1994, 4, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brothwell, D. Further evidence of bone chewing by ungulates—The sheep of North Ronaldsay, Orkney. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1976, 3, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meckel, L.A.; McDaneld, C.P.; Wescott, D.J. White-Tailed Deer as a Taphonomic Agent: Photographic Evidence of White-Tailed Deer Gnawing on Human Bone. J. Forensic Sci. 2018, 63, 292–294. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28464354 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, I.; Esteban-Nadal, M.; Bennàsar, M.; Fernández-Jalvo, Y. Was it the deer or the fox? J. Archaeol. Sci. 2011, 38, 2767–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.L.; Haynes, G. Camels as taphonomic agents. Quat. Res. 1985, 24, 365–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, G. Frequencies of spiral and green-bone fractures on ungulate limb bones in modern surface assemblages. Am. Antiq. 1983, 48, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrensmeyer, A.K.; Gordon, K.D.; Yanagi, G.T. Trampling as a cause of bone surface damage and pseudo-cutmarks. Nature 1986, 319, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford-Gonzalez, D. An Introduction to Zooarchaeology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Magoun, A.J. Summer scavenging activity in Northeastern Alaska. In Proceedings of the Conference on Scientific Research in the National Parks, New Orleans, LA, 9–12 November 1976; Volume 1, pp. 335–340. [Google Scholar]

- France, D.L.; Griffin, T.J.; Swanburg, J.G.; Lindemann, J.W.; Davenport, G.C.; Trammell, V.; Travis, C.T.; Kondratieff, B.; Nelson, A.; Castellano, K.; et al. Necrosearch revisited: Further multidisciplinary approaches to the detection of clandestine graves. In Forensic Taphonomy: The Postmortem Fate of Human Remains; Sorg, M.H., Haglund, W.D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997; pp. 497–509. [Google Scholar]

- Demo, C.; Cansi, E.R.; Kosmann, C.; Pujol-Luz, J.R. Vultures and others scavenger vertebrates associated with man-sized pig carcasses: A perspective in forensic taphonomy. Zoologia 2013, 30, 574–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fetner, R.A.; Sołtysiak, A. Shape and distribution of griffon vulture (gyps fulvus) scavenging marks on a bovine skull. J. Taphon. 2013, 11, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Pharr, L. Comparison of vulture scavenging rates at the Texas state forensic anthropology research facility versus off-site, non-forensic locations. In Proceedings of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences 64th Annual Scientific Conference, Atlanta, GE, USA, 20–25 February 2012; Volume XVIII, p. 356. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, K.N. The Effects of Clothing on Vulture Scavenging and Spatial Distribution of Human Remains in Central Texas; Texas State University: San Marcos, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Halley, D.J.; Gjershaug, J.O. Inter- and intra-specific dominance relationships and feeding behaviour of eagles at carcasses. IBIS 1998, 140, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, W.J.; Trapani, J.; Mitani, J.C. Taphonomic aspects of crowned hawk-eagle predation on monkeys. J. Hum. Evol. 2003, 44, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapani, J.; Sanders, W.J.; Mitani, J.C.; Heard, A. Precision and consistency of the taphonomic signature of predation by crowned hawk-eagles (stephanoaetus coronatus) in Kibale National Park, Uganda. Palaios 2006, 21, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewson, R. Scavenging of mammal carcases by birds in West Scotland. J. Zool. 1981, 194, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamura, H.; Takayanagi, K.; Ota, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Fukushima, H. Unusual characteristic patterns of postmortem injuries. J. Forensic Sci. 2004, 49, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A. An Investigation of Patterns of Mammalian Scavenging in Relation to Vertebrate Skeletal Remains. Ph.D. Thesis, Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dettling, A.; Strohbeck-Kühner, P.; Schmitt, G.; Haffner, H.T. Tierfrass durch einen singvogel? Archiv. Kriminol. 2001, 208, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Pokines, J.T. Preliminary Study of Gull (Laridae) Scavenging and Dispersal of Vertebrate Remains, Shoals Marine Laboratory, Coastal New England. J. Forensic Sci. 2022, 1–8. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35076105 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, A. Vulture Scavenging of Pig Remains at Varying Grave Depths. Master’s Thesis, Texas State University, San Marcos, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, R.R.; Seibold, H.; Heurich, M. Invertebrates Outcompete Vertebrate Facultative Scavengers in Simulated Lynx Kills in the Bavarian Forest 132 National Park, Germany. Anim. Biodivers. Conserv. 2014, 37, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Rogers, C.J.; Cassella, J.P. Why does the UK Need a Human Taphonomy Facility? Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 296, 74–79. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30708265 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Pecsi, E.L.; Bronchti, G.; Crispino, F.; Forbes, S.L. Perspectives on the Establishment of a Canadian Human Taphonomic Facility: The Experience of Rest(ES). Forensic Sci. Int. Synerg. 2020, 2, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockle, D.L.; Bell, L.S. The impact of trauma and blood loss on human decomposition. Sci. Justice 2019, 59, 332–336. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31054822 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Spies, M.J.; Finaughty, D.A.; Friedling, L.J.; Gibbon, V.E. The Effect of Clothing on Decomposition and Vertebrate Scavengers in Cooler Months of the Temperate Southwestern Cape, South Africa. Forensic Sci. Int. 2020, 309, 110197. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32114190 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.G.; Dabbs, G.R. A Taphonomic Study Exploring the Differences in Decomposition Rate and Manner between Frozen and never Frozen Domestic Pigs (Sus Scrofa). J. Forensic Sci. 2015, 60, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, C.A.; Rafuse, D.J.; González, M.E.; Álvarez, M.C.; Massigoge, A.; Scheifler, N.A.; Gutiérrez, M.A. Carcass Utilization and Bone Modifications on Guanaco Killed by Puma in Northern Patagonia, Argentina. Quat. Int. 2016, 466, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorg, M.H. Differentiating Trauma from Taphonomic Alterations. Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 302, 109893. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31419593 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, C.; Cappella, A. Distinguishing between peri- and post-mortem trauma on bone. In Taphonomy of Human Remains. Forensic Analysis of the Dead and the Depositional Environment: Forensic Analysis of the Dead and the Depositional Environment; Schotsmans, E.M.J., Márquez-Grant, N., Forbes, S.L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 352–368. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, W.M.; Driscoll, P.A. Summary of Skeletal Identification in Tennessee: 1971–1981. J. Forensic Sci. 1983, 28, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, J.C. Sharp force trauma analysis in bone and cartilage: A literature review. Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 299, 119–127. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30991210 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunawardena, S.A. Artefactual Incised Wounds due to Postmortem Predation by the Sri Lankan Water Monitor (Kabaragoya). Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2016, 12, 324–330. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27216749 (accessed on 16 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Felid | Canid | Ursid | Mustelid | Procyonid | Suid | Rodent | Cervid/Bovid | Birds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behaviour | |||||||||

| Soft tissue consumption | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | X |

| Bone consumption | (x) | X | X | X | (x) | X | X | X | (x) |

| Transport | X | X | X | X | - | - | X | - | X |

| Caching | X | X | - | X | - | - | X | - | X |

| Trampling | - | - | - | - | - | X | - | X | - |

| Bone modifications | |||||||||

| Claw marks | X | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | X |

| Conical pits | X | X | X | X | (x) | - | - | - | - |

| Irregular pits | X | X | X | X | (x) | X | - | - | X |

| Punctures | X | X | X | X | (x) | (x) | - | - | X |

| Scores | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | X | X |

| Furrows | X | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | - |

| Epiphyseal removal | (x) | X | X | X | - | X | - | (x) | (x) |

| Scooping | - | X | X | X | - | - | - | - | - |

| Crenulated edges | X | X | X | X | (x) | X | - | - | - |

| Spiral fractures | (x) | X | X | (x) | - | (x) | - | - | - |

| Splintering | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | X | - |

| High fragmentation | - | X | - | X | - | X | - | X | - |

| Pedestalling | - | - | - | - | - | - | X | - | - |

| Windows | - | - | - | - | - | - | X | - | - |

| Small, parallel striations | - | - | - | - | - | - | X | X | - |

| Notches along border | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | X |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Indra, L.; Errickson, D.; Young, A.; Lösch, S. Uncovering Forensic Taphonomic Agents: Animal Scavenging in the European Context. Biology 2022, 11, 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11040601

Indra L, Errickson D, Young A, Lösch S. Uncovering Forensic Taphonomic Agents: Animal Scavenging in the European Context. Biology. 2022; 11(4):601. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11040601

Chicago/Turabian StyleIndra, Lara, David Errickson, Alexandria Young, and Sandra Lösch. 2022. "Uncovering Forensic Taphonomic Agents: Animal Scavenging in the European Context" Biology 11, no. 4: 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11040601

APA StyleIndra, L., Errickson, D., Young, A., & Lösch, S. (2022). Uncovering Forensic Taphonomic Agents: Animal Scavenging in the European Context. Biology, 11(4), 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11040601