1. Introduction

As industries seek to reduce their environmental footprint, interest in plant-based fibres is growing, especially for use in composite materials [

1]. Among these, flax fibre—used in textiles for millennia—is particularly valued for its mechanical properties, which are comparable to those of synthetic fibres such as glass fibre [

2]. This rising interest has driven steady growth in demand, but production struggles to keep pace, largely due to climate change, which introduces new uncertainties into farming practices and yields. France is the largest producer of fibre flax globally, with main growing regions along the English Channel coast, where mild temperatures and regular rainfall create favourable conditions. However, this region is increasingly exposed to climate-related risks, including rising temperatures and more frequent extreme events such as droughts and floods [

3]. Projections indicate that temperatures in these areas may increase by up to 3 °C by the end of the century under a high-emissions scenario [

3]. Particularly concerning is the increasing frequency and severity of heatwaves, as flax is highly sensitive to temperatures above 30 °C. Its optimal growth range is 15–20 °C [

4,

5], and under pessimistic scenarios, the number of days exceeding 25 °C could increase by more than 40 annually in Normandy [

3]. Inland regions, without the coast’s moderating effect, could be even more severely impacted.

Due to its relatively short cultivation cycle of 100 to 120 days [

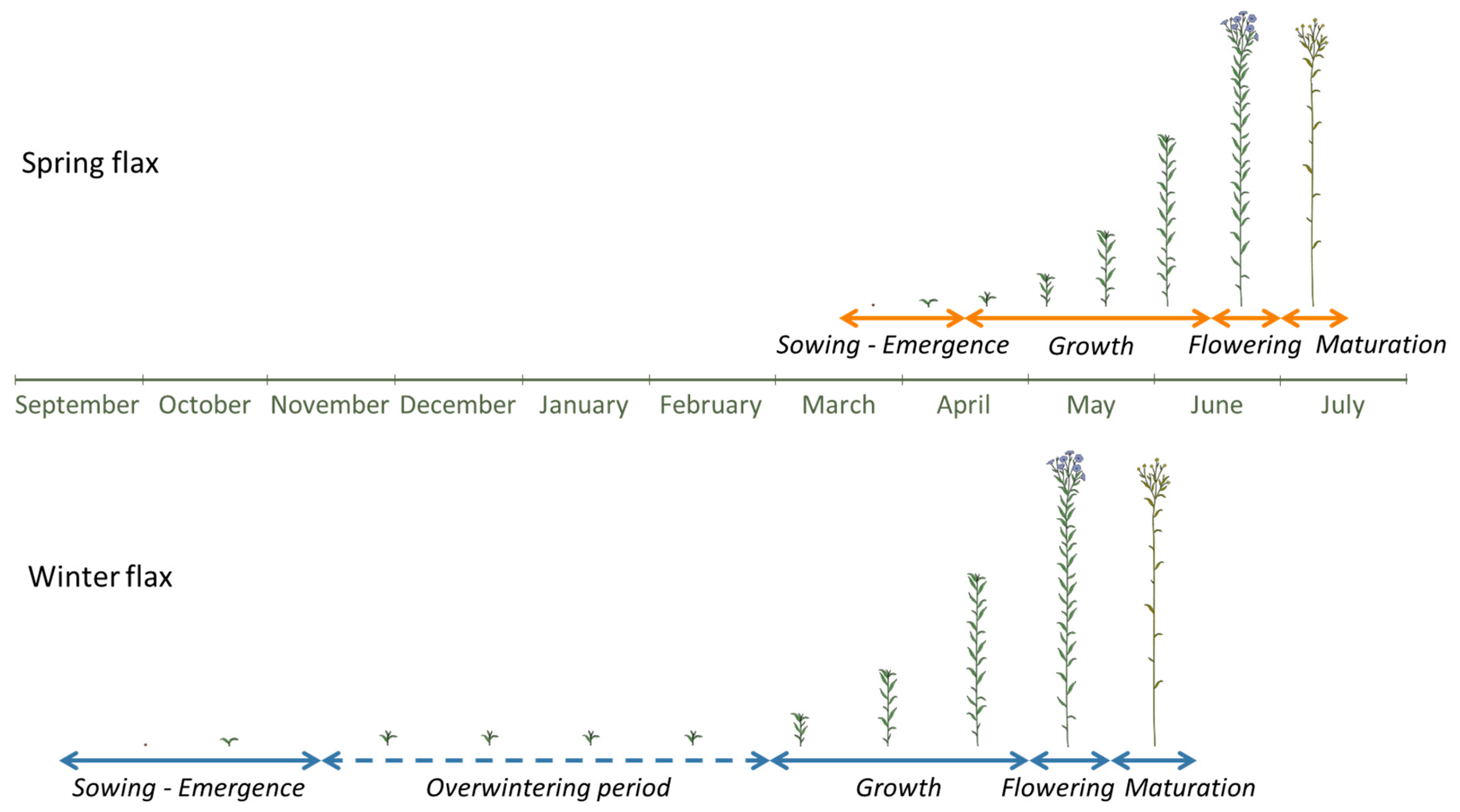

6] (

Figure 1), and narrow climatic tolerance, flax is particularly vulnerable to climate variability. Sowing typically takes place between 15 March and 15 April [

7], and germination follows within about ten days. After a slow initial growth phase of 15–20 days, the plants enter a rapid growth phase, gaining over 50 cm in height in just two weeks [

8]. Fibre cells elongate for 2 to 4 days by intrusive growth, at a rate of 1–2 cm per day [

9]. Growth gradually slows during flowering, followed by seed formation and fibre maturation, at which point the flax is harvested. These phenological stages are closely linked to cumulative growing degree days (GDD) from sowing [

10], with fibre maturity typically reached at cumulative GDD values between 950 and 1100 °C days [

6].

Droughts in May or June, which coincide with the main growth phase, can be particularly limiting to plant development and lower yields [

11]. Moreover, higher temperatures drive increased evapotranspiration, reducing soil moisture even when annual rainfall remains stable. While soil drought in flax-growing regions in France previously peaked in August, it could extend from May to November by the end of the century under continued high emissions. This is critical, as flax needs 110–150 mm of rainfall during May and June for optimal fibre development [

12]. Such growing conditions strongly influence both the plant’s morphology and its biochemical profile. Under drought stress, flax and other terrestrial plants tend to produce more lignin, with increases of up to 29% in fibre bundles reported under water stress [

11,

13,

14]. Changes in carbohydrate composition have also been observed, including reduced glucose, increased mannose [

11], and lower galactan levels, all of which can affect cell wall properties [

15].

To adapt to climate change, one promising strategy under investigation is shifting from spring to winter cultivation in countries such as France, Belgium, and the Netherlands [

16]. A precedent exists in oilseed flax, whose winter varieties were developed in the 1980s and 1990s by crossing French lines with cold-tolerant Turkish varieties [

17,

18]. Winter fibre flax appeared about a decade later. Previously almost absent from French fields, winter fibre flax has expanded rapidly after 2021 from just 5000 hectares in 2022 to 30,000 hectares in 2024—about 13% of the total textile flax area [

19]. In some French regions, winter flax accounted for over 40% of fibre flax acreage in 2024 [

20]. That year, eight winter fibre flax varieties were commercially available, compared with 26 spring varieties [

21].

Winter flax is sown in autumn, between September and November, depending on location (

Figure 1). Coastal areas typically sow later than inland regions [

21]. For successful overwintering, the plants should remain under 5 cm in height when winter sets in, having accumulated at least 250 °C days before the first frost and 500 °C days before the coldest period, which usually corresponds to about 7 cm in height [

22]. Plants should not exceed 10 cm before the end of winter, as cells at this height become turgid and more vulnerable to temperature fluctuations [

22].

This study aimed to evaluate how seasonal growing conditions affect flax production and to determine whether a spring variety could be reliably grown in winter, particularly regarding cold tolerance. The rising demand and limited supply of winter flax seed make this assessment especially relevant. Moreover, using the same variety in both regimes ensured that any differences reflected environmental effects rather than genetics. The Elixir spring flax was grown for four consecutive years at the same site to assess interannual variability, and in 2023 it was cultivated in both spring and winter to allow direct comparison. Plant architecture, elementary fibre length, and mechanical properties were analysed, followed by an assessment of monosaccharide and lignin contents in the scutched fibres. These results provide insight into the potential of winter cultivation as an adaptation strategy for the flax sector under climate change.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Elixir Flax Variety: Spring and Winter Crops

The Elixir spring flax variety, first marketed by Terre de Lin in 2017, is one of the highest yielding for fibre production but is particularly sensitive to water stress. It was cultivated over four consecutive years (2021–2024) in Busnes (Pas-de-Calais, France) by the same grower and using consistent agricultural practices. Each year, a different plot (5–6.5 hectares) was used, in compliance with crop rotation regulations that require at least a seven-year interval before replanting flax on the same land.

This variety was also cultivated under experimental conditions by Terre de Lin, i.e., in micro-plots, following the same soil preparation, both as a winter and a spring crop in the same year (2023). The winter crop was sown on 11 October 2022 in La Vieille-Lyre (Eure, France) and harvested on 30 June 2023. The spring crop was sown on 2 May 2023 in Angiens (Seine-Maritime, France) and harvested on 11 August 2023. Sowing of spring flax in 2023 was delayed by about one month due to unfavourable weather, as heavy rainfall in March and April prevented soil preparation.

After dew retting, the flax stems were scutched by the Arvalis Applied Agricultural Research Institute. The elementary fibres analysed in this study were manually extracted following scutching.

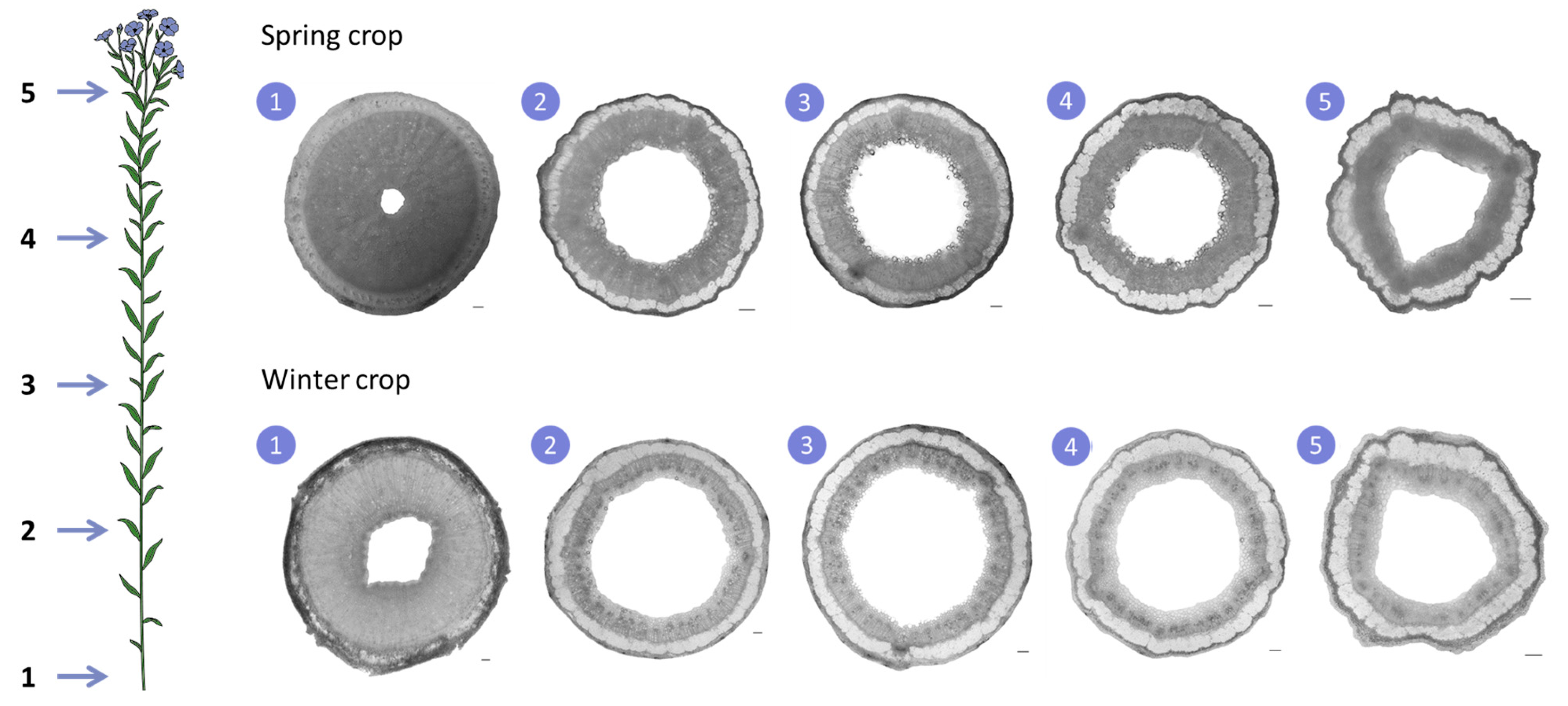

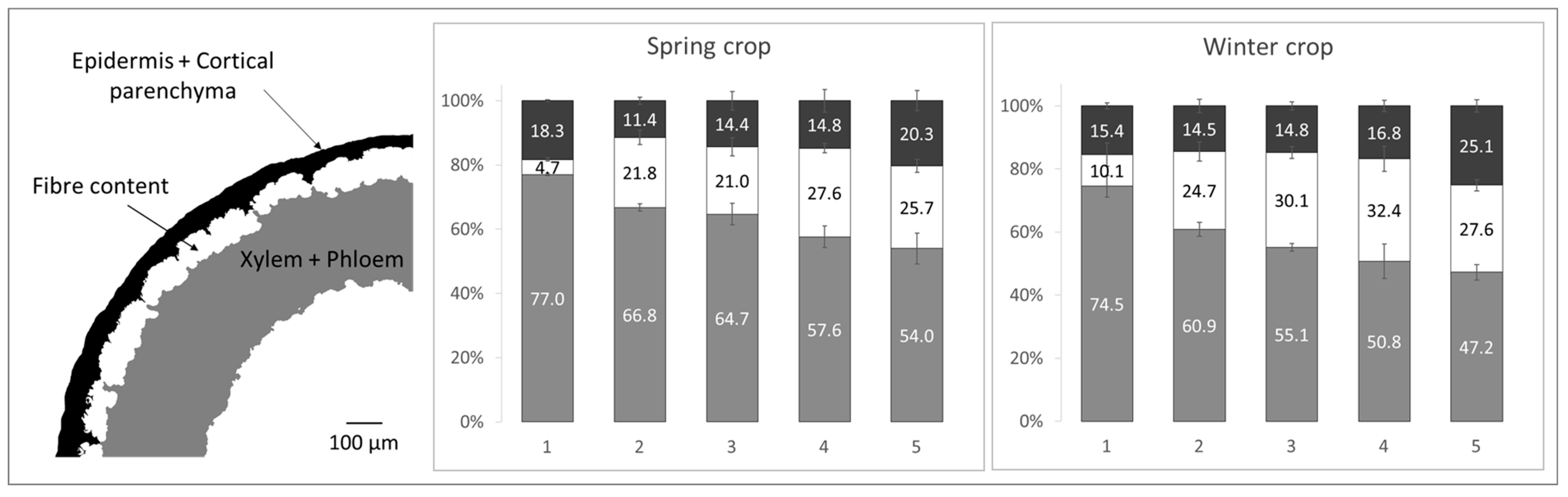

2.2. Analysis of Internal Stem Architecture

For each batch, the stem diameter of 15 plants was measured using a calliper. The total height (from collar to apex) and technical height (from collar to first branch) were measured on the same 15 stems using a measuring tape. For histological analysis, cross-sections were prepared at five different heights along each stem. The stems were preserved in a fixative solution of 70% ethanol and 30% distilled water. Sections 200 to 300 µm thick were cut using a Leica VT1000 vibratome (Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany) to facilitate observation under a Keyence VHX-7000 optical microscope.

Images of the cross-sections were analysed using ImageJ® software (version 1.54). The number of elementary fibres per section was counted, and the distribution of tissues along the stem height was examined. The apparent tissue area relative to the total cross-sectional area was determined, as well as the proportional areas of the individual tissue components. For this analysis, tissues were classified into three categories: fibres; xylem plus phloem; and cortical parenchyma plus epidermis. Averages were calculated from at least three sections per sample.

2.3. Measurement of Elementary Fibre Length

In each batch, the lengths of elementary fibres were measured at the bottom, middle, and top of the stems. In each region, 25 individual fibres were manually extracted, and measured using the Keyence VHX-7000 optical microscope. Panoramic images and the microscope’s integrated measurement tools were used for length determination.

2.4. Tensile Testing of Elementary Fibres

Tensile tests were performed on elementary fibres in a controlled environment (23 ± 2 °C and 50 ± 5% relative humidity). Fibres were mounted on a plastic support and secured using a UV-curable adhesive (DYMAX, Wiesbaden, Germany). Diameters were first measured with an FDAS device (Fibre Dimensional Analysis System; Dia-Stron Ltd., Andover, Hampshire, UK). The mean diameter for each fibre was calculated from 10 measurements along its length. Tensile testing was carried out using a LEX820 system (Dia-Stron Ltd., Hampshire, UK) with a gauge length of 10 mm and elongation rate of 1 mm s−1. Approximately 80 fibres were tested and validated per batch.

2.5. Biochemical Analysis of Scutched Fibres

For each crop, a 1 g sample of fibres was taken from the mid-height of the scutched flax and homogenised by cryogrinding in liquid nitrogen using a Freezer/Mill® 6770 (SPEX SamplePrep, Metuchen, NJ, USA).

Cryo-ground fibres were characterised following the method described by Gautreau et al. [

23]. Neutral monosaccharides and their alditol acetates [

24] were analysed by gas chromatography with flame ionisation detection (GC-FID) (Perkin Elmer, Clarus 580, Shelton, CT, USA). Glucuronic and galacturonic acids were quantified using the method of Blumenkrantz and Asboe-Hansen [

25]. Reported values for both samples are means of three independent replicates. Total monosaccharide content was calculated as the sum of neutral and acidic monosaccharides.

Lignin content was determined by spectrophotometry using the acetyl bromide method [

26]. Three 20 mg subsamples were analysed per batch. All chemicals were laboratory grade (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Results are expressed as a percentage of dry matter weight and correspond to the mean of three independent trials.

The ratios of H, G, and S lignin monomers were determined following Kairouani et al. [

27]. For each batch, 5 mg of sample were analysed in triplicate, and 1 µL of trimethylsilylated extract was injected into an Agilent 6990 GC Chromatography System coupled to an Agilent 5973 Mass Selective Detector (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

To determine whether the mechanical properties of the two fibre batches differed significantly, a Student’s t-test (T.TEST function in Microsoft Excel) was used to compare means, assuming approximately normal data distribution and independent samples, the objective of the study being to perform targeted pairwise comparisons between cultivation years and between different positions of the fibres within the plant. p < 0.05 is assumed to indicate statistical significance.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Interannual Variation in Yield and Mechanical Properties of Elixir Spring Flax Fibres

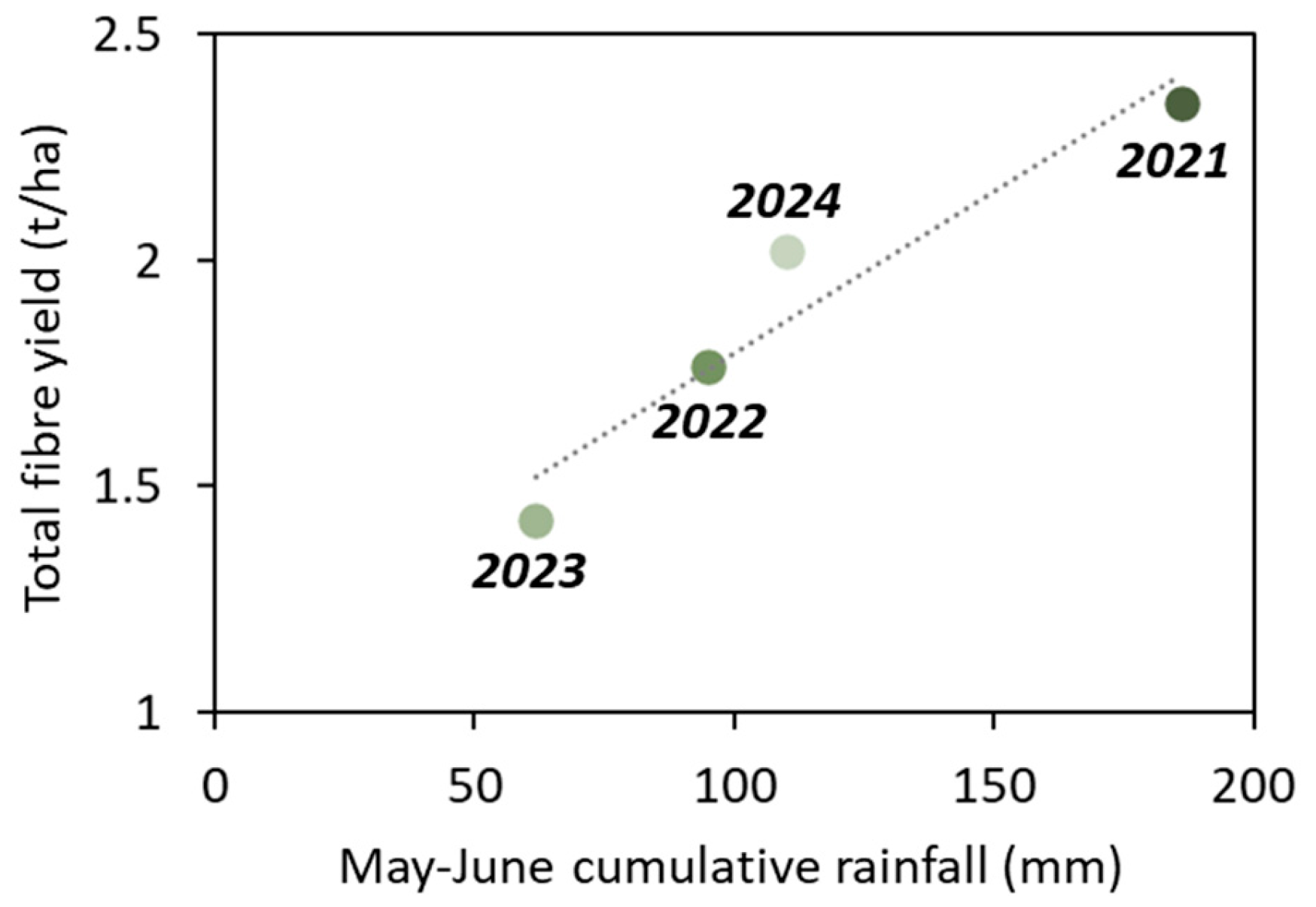

Over the four years of Elixir spring flax cultivation, temperatures remained generally mild, with no heatwaves and maximum daily temperatures staying below 25 °C—favourable conditions for flax growth. In contrast, rainfall showed marked interannual variability (

Figure 2). While favourable conditions prevailed in 2021 and 2024, with total rainfall during the key vegetative period (1 May–30 June) reaching 186 mm and 110 mm, respectively, the springs of 2022, and particularly 2023, were characterised by significant water deficits that notably impacted fibre production. May–June rainfall totalled just 95 mm in 2022 and only 62 mm in 2023, with an extended dry spell from mid-May to mid-June.

These rainfall fluctuations strongly affected fibre yield, revealing a near-linear relationship (

Figure 2). In 2023, the driest year, fibre yield fell to just 1.4 t ha

−1. In contrast, the 2021 crop, which received nearly three times as much rain, produced the highest yield at 2.3 t ha

−1. Yields for 2022 and 2024 were intermediate, at 1.8 t ha

−1 and 2.0 t ha

−1, respectively.

Between 1969 and 2024, the national average yield for total flax fibre production in France was about 1.9 t ha

−1. Flax typically requires 110–150 mm of rainfall during vegetative growth for optimal development [

12]. It is therefore unsurprising that yields in 2022 and 2023, both years with rainfall well below this range, fell short of the long-term national mean. These results highlight how crucial adequate spring rainfall is for fibre production and underscores flax’s vulnerability to drought during this period.

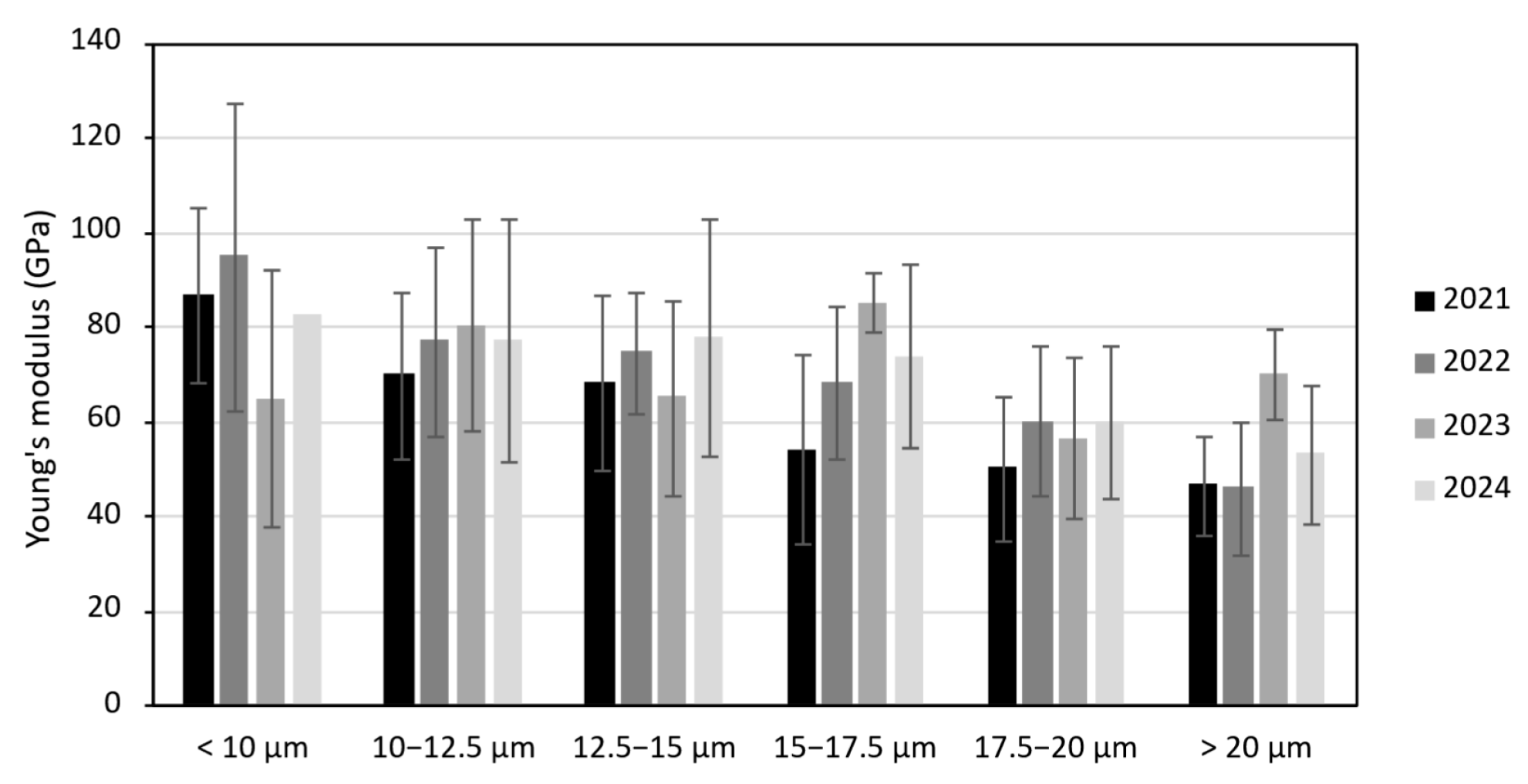

To examine whether growing conditions influenced fibre quality, tensile tests were conducted on elementary fibres from the four Elixir crops. The results are shown in

Table 1.

The diameter of the tested fibres varied significantly between years. Fibres from the drought-affected 2023 crop had the smallest average diameter (11.6 µm), while those from 2024 were the thickest (18.2 µm). These differences in diameter partly explain variations in mean modulus: the finer 2023 fibres showed the highest average Young’s modulus (71.2 GPa). However, when modulus is analysed by fibre diameter class, it is evident that fibres of similar diameter have comparable stiffness across all crops (

Figure 3). Fibres thinner than 10 µm tended to show moduli up to twice those of thicker fibres (>20 µm). This probably reflects overestimation of cross-sectional area for thicker fibres, given the challenge of measuring a diameter that is neither constant nor perfectly circular. The slightly higher modulus seen in the 2023 fibres for the 15–17.5 µm and >20 µm diameter classes is not meaningful, as only a handful of fibres were tested in these ranges (

n = 3 and

n = 2, respectively).

Tensile strength was statistically similar across the four years, ranging from 1100 to 1400 MPa. Elongation at break was also consistent, between 1.7% and 2.1%.

Overall, these results suggest that the mechanical properties of Elixir flax fibres are largely stable from year to year, despite interannual variability in meteorological conditions. This stability is encouraging for end users, as it indicates that fibre quality for textiles and composites can be maintained even under varying climatic conditions. Nonetheless, other important quality aspects, such as batch uniformity and fibre colour, may still vary and require further attention to ensure overall product consistency.

However, year-to-year variation in yield remains significant, posing challenges for supply stability and grower income. This vulnerability is driving the search for adaptation strategies, including increased adoption of winter flax. The properties of winter flax plants and fibres have been examined in previous studies [

16], but these investigations focused on specific winter varieties. To more accurately assess the influence of winter versus spring growing conditions on yield and fibre characteristics, the following section compares the Elixir spring variety grown as both a spring and a winter crop in 2023.

3.2. Weather Conditions During the Growth of Spring and Winter Crops in 2023

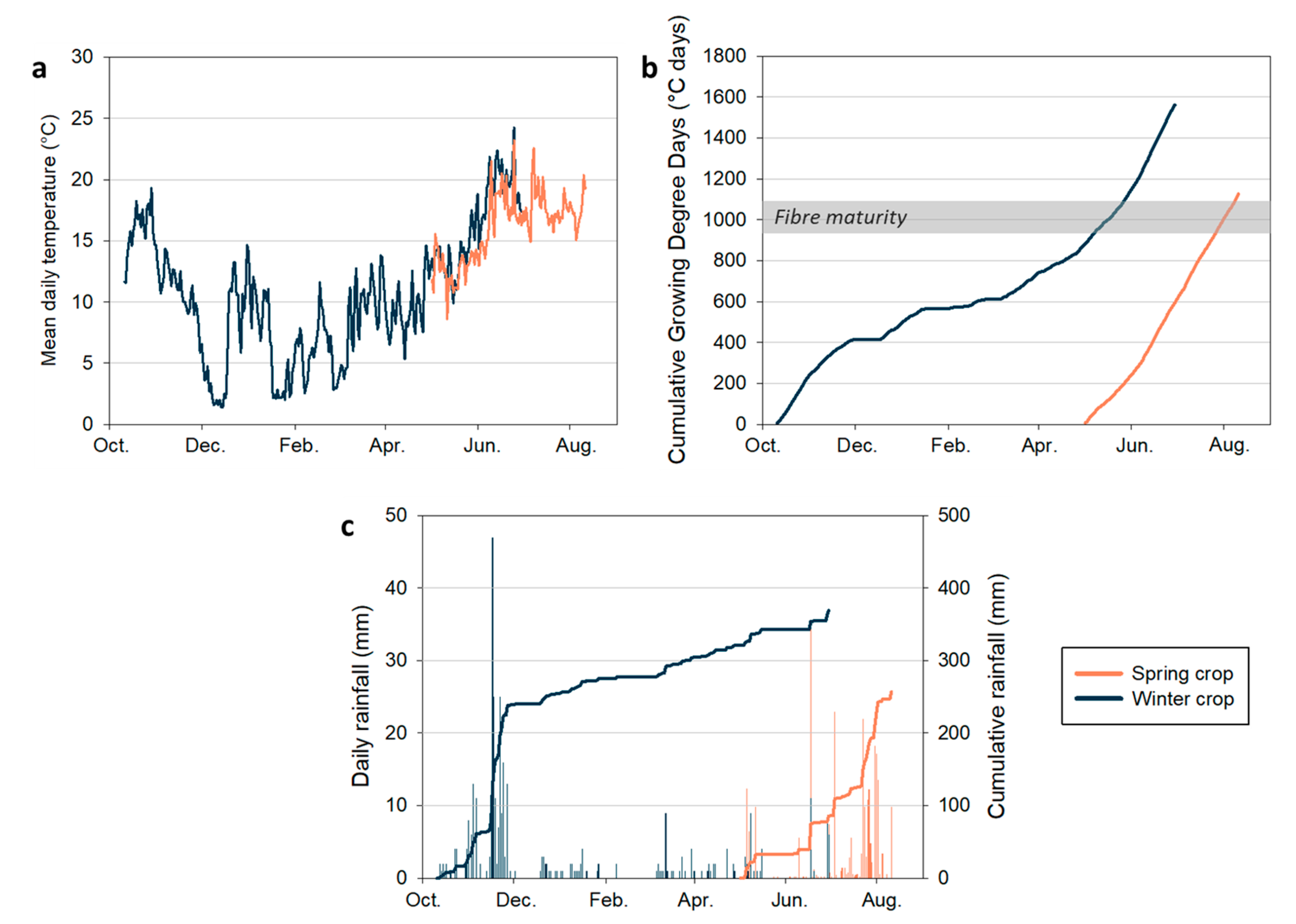

The year 2023 presented highly contrasting conditions for flax production, proving favourable for winter flax but exceptionally challenging for spring flax. Temperatures during the winter of 2022-2023 were relatively mild, never dropping below 0 °C, with no severe frost events recorded in early spring (March and April;

Figure 4a). Between 11 October and 1 December, total rainfall reached 240 mm, followed by little to no precipitation in February (

Figure 4c). Regular rainfall from March to May, combined with mild temperatures, created near-ideal conditions for winter crop. In contrast, persistent rainfall in March and April delayed soil preparation for spring flax, pushing sowing to early May, over a month behind schedule. In the two weeks following sowing, 33 mm of rain fell (

Figure 4c). From mid-May to mid-June—the critical growth phase—a prolonged dry period combined with persistent winds further depleted soil moisture. This is when flax is most sensitive to water stress [

28]. Moreover, wind action can hinder stem elongation [

29]. Summer brought more rainfall, but temperatures remained moderate, rarely exceeding 25 °C (

Figure 4a,c). The hottest day was 25 June, with a maximum temperature of 30.7 °C. Between 1 July and 11 August, the average temperature was 17.6 °C. These conditions allowed the spring flax to develop, but its late sowing and early-season drought resulted in stunted plants and yields well below average. Together, these two crops exemplify the increasing challenges facing flax production: a mild winter that benefited the winter crop and a spring drought that severely constrained the spring crop.

Thermal time (cumulative daily mean temperature) was calculated from sowing to harvest (

Figure 4b). Spring flax fibre maturity is generally reached when cumulative growing degree days (GDD) reach 950–1100 °C days [

6]. Despite the late sowing, the spring crop reached a cumulative GDD value of 1126 °C days, indicating that fibre maturity was nevertheless achieved. For the winter crop, cumulative GDD reached 1562 °C days; however, this value should be interpreted with caution, as no consensus yet exists on GDD thresholds for winter flax cultivation.

3.3. Analysis of Stem Structure in Spring and Winter Crops

The stem dimensions differed notably between the spring and winter crops. Although grown on different plots, and despite potential influences from soil fertility, crop rotation, and wind exposure, weather conditions were clearly the primary driver of the observed differences. Winter flax stems averaged 114.7 ± 3.3 cm in total height, 105.9 ± 4.5 cm in technical height, and 1.96 ± 0.42 mm mid-stem diameter, whereas spring flax stems were significantly shorter and thinner, with 72.8 ± 6.8 cm total height, 63.7 ± 4.4 cm technical height, and 1.46 ± 0.17 mm mid-stem diameter. For reference, fibre flax typically reaches 80–90 cm [

21]. The greater height of the winter crop indicates highly favourable growth conditions, while the stunted spring flax reflects severe water stress.

Analysis of stem cross-sections showed a slightly higher tissue proportion at mid-stem in spring flax (71.8 ± 1.8%) compared to winter flax (62.7 ± 1.2%), mainly due to a thinner xylem layer in the winter flax (

Figure 5). The xylem transports water and nutrients from roots to shoots, a process driven by evapotranspiration. In winter, lower temperatures reduce water loss, slowing sap flow and thus reducing the need for extensive xylem vessels, explaining the observed difference. These results align with previous studies reporting about 63% tissue for winter flax [

16] and 70–85% for spring flax [

30]. After scutching, the lower shive yield from winter flax has minimal economic impact due to its low market value relative to fibres.

Flax stem tissue consists of xylem, phloem, fibres, cortical parenchyma, and epidermis. Examining the distribution of these components along the stem shows similar patterns for both crops (

Figure 6): the xylem is thickest at the base providing structural support and thins towards the top, while the epidermis is thicker near the first branches. The fibre layer, which provides mechanical strength, differed slightly between crops: the winter flax showed a higher fibre proportion in sections 3 and 4 (mid-upper stem), while the spring flax peaked in sections 4 and 5 (upper stem). In spring flax, the number of fibres per cross-section reached a maximum of 842 ± 149 at level 4 (

Table 2), aligning with previous findings for the Marylin variety (898 fibres at mid-height with a 1.52 mm stem diameter) [

31]. Other spring varieties typically show 800–1300 fibres at mid-height, for about 2 mm stem diameter [

30]. In the winter flax, fibres were predominantly concentrated at mid-height, yielding twice as many fibres as the spring crop at this level and more than in our previous study [

16].

This lower fibre count in the spring crop highlights the impact of water stress on fibre production. In contrast, the favourable conditions for the winter crop resulted in denser fibre development, illustrating the potential of winter cultivation to offset some climate-related risks.

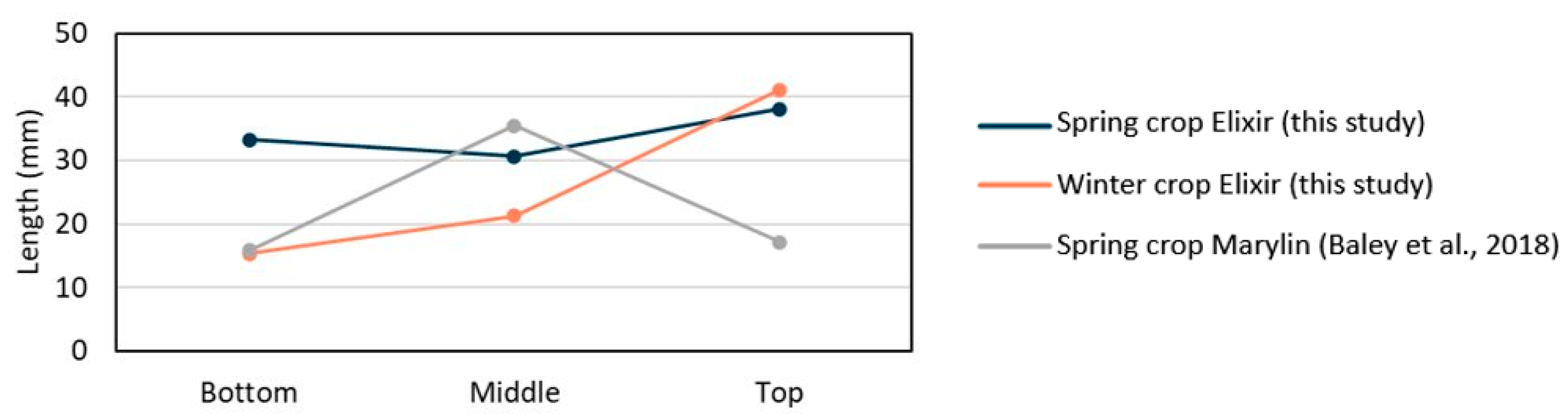

3.4. Elementary Fibre Length

The lengths of fibres from the base, middle, and top of the stems were measured for spring and winter Elixir crops (

Table 3). In the spring crop, fibre length remained relatively uniform along the stem, ranging from 31 to 38 mm. In contrast, fibres at the top of the winter crop were on average 2.7 times longer than those at the base—consistent with observations for other winter flax varieties [

16]. All measured lengths fell within the range reported in the literature for flax elementary fibres (2–65 mm) [

31,

32,

33].

The same variety thus showed significant variation in fibre length depending on the cultivation regime, demonstrating the strong influence of growth conditions on fibre elongation. During plant growth, fibre cells elongate in just a few days [

32]. Although flax can grow at temperatures as low as 5 °C, rapid elongation occurs at 15–20 °C [

4]. Fibres from the top of the stems showed no significant difference between spring and winter crops because they formed during the same late spring period. Fibres from other stem levels were significantly shorter in the winter crop, reflecting the slower cumulative GDD increase during early vegetative growth: the average temperature from October to March for the winter crop was 8.5 °C, compared to 12.7 °C in May, the first month of growth for the spring crop. This explains the more uniform fibre lengths along the spring stems (near linear cumulative GDD; cf.,

Figure 4b) versus the sharp gradient in the winter crop, where cooler days during the early growth phase limited cell elongation.

A comparison with the standard Marylin spring flax variety [

31] further illustrates this effect (

Figure 7). The Marylin crop was cultivated in Normandy in 2012 under typical conditions: April-July temperature averaged 13.4 °C, with 220 mm of rainfall, 1 day of frost (<0 °C), and 9 hot days (>25 °C)—close to the long-term regional norm [

3]. At the base, Marylin fibre lengths matched those of the Elixir winter crop; at mid-height, they matched the base of the delayed Elixir spring crop, confirming the strong climate influence on fibre elongation. However, at the top of the stems, the Marylin fibres were significantly shorter despite the favourable climate conditions—likely due to an unreported chemical treatment such as a fungicide, which may have prematurely halted cell development.

These results show that elementary fibre length is primarily driven by temperature during elongation rather than by water availability. Although the spring crop endured drought and developed fewer fibres, their length remained suitable for textile applications. For winter flax, however, short fibres in the lower stem may complicate processing with conventional spinning methods.

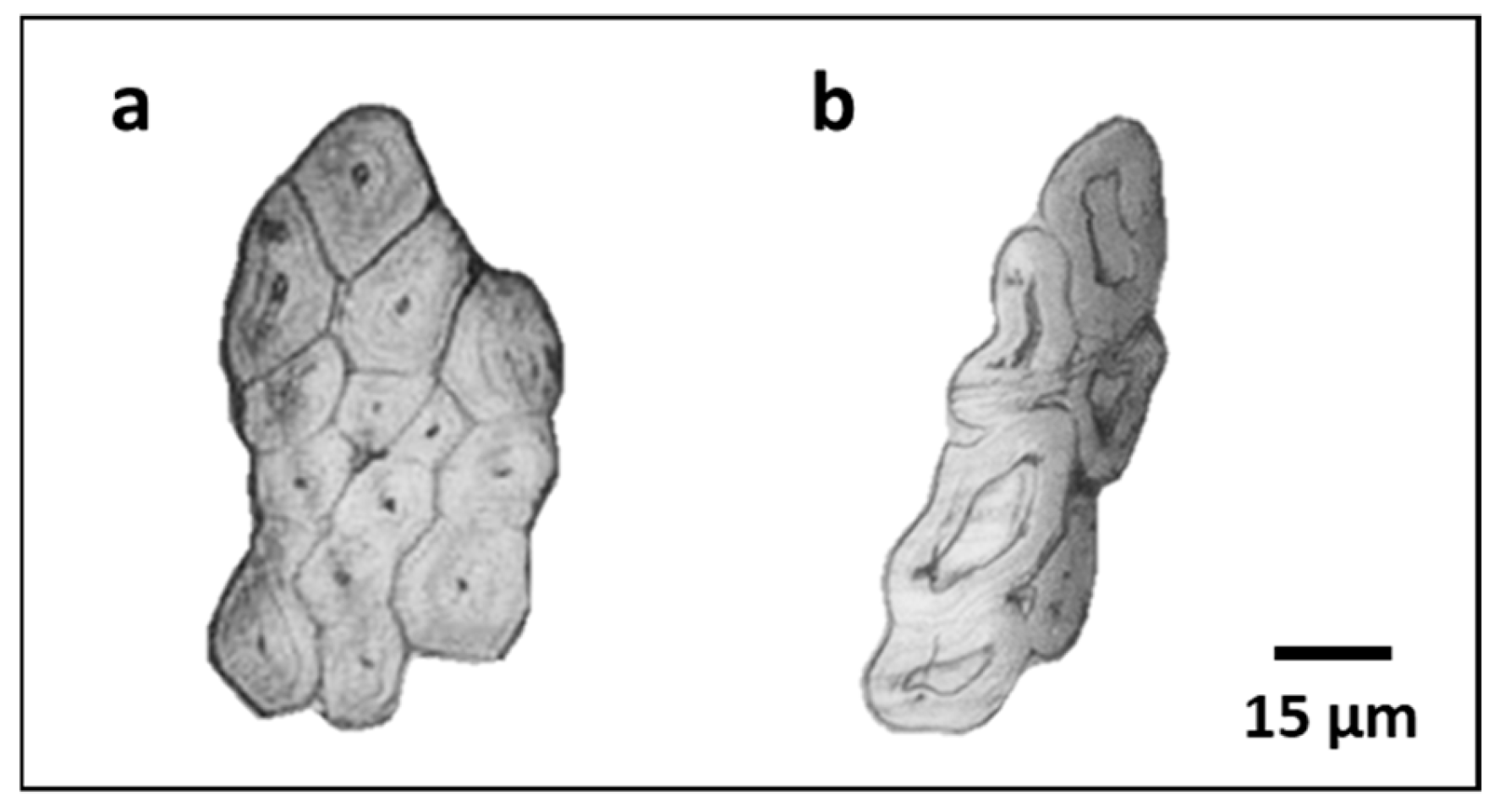

3.5. Mechanical Properties of Elementary Fibres

Examining the tensile properties of the elementary fibres (

Table 4), we find that their diameter decreases with increasing stem height for both crops, in line with previous observations for spring [

34] and winter flax [

16]. At the base, fibre diameters were statistically similar between both crops. At mid-height and the top, however, spring flax fibres were about 10% thinner—likely due to drought stress, which is known to produce narrower fibres [

11,

28].

Tensile strength at the top of the stems was statistically similar between crops (

p > 0.05). However, spring flax fibres had a higher Young’s modulus, consistent with their smaller diameters. At mid-height, mechanical properties were comparable for both crops and consistent with compiled reference values for spring flax: Baley and Bourmaud reported average Young’s modulus, tensile strength, and elongation values of 52.5 ± 8.6 GPa, 945 ± 200 MPa, and 2.1 ± 0.5%, respectively, for fibres with an average diameter of 16.8 ± 2.7 µm [

35]. This shows that Elixir fibres’ mid-stem performance aligns with well-established benchmarks.

At the base, spring crop fibres outperformed those of winter crop, with a Young’s modulus, tensile strength, and elongation 17%, 32%, and 20% higher, respectively. Since their diameters were equivalent, fibre cross-sections were examined under a microscope (

Figure 8). Winter flax fibres from the base showed larger lumens, indicating incomplete cell wall thickening. Flax fibre cells mature by inward thickening of the secondary wall [

6]; a large lumen therefore suggests immature fibres, which can result from chemical treatments—including growth regulators, which prematurely interrupt development—, reduced soil quality, or environmental stress. Incomplete filling reduces mechanical performance [

36], explaining the inferior tensile properties of the winter fibres at the base.

3.6. Biochemical Analysis of Fibres

A biochemical analysis of the fibres from the spring and winter crops of the Elixir variety was conducted. While fibres from both crops showed generally comparable mechanical properties, winter flax fibres were often coarser and less well individualised after retting and scutching. Although the retted fibres from the winter crop appeared visually more retted—suggested by their greyer colour compared to the still-yellow spring flax fibres—their monosaccharide and lignin contents were analysed to understand why the majority of the winter flax fibres remained more tightly bound together despite this apparent indication of good retting.

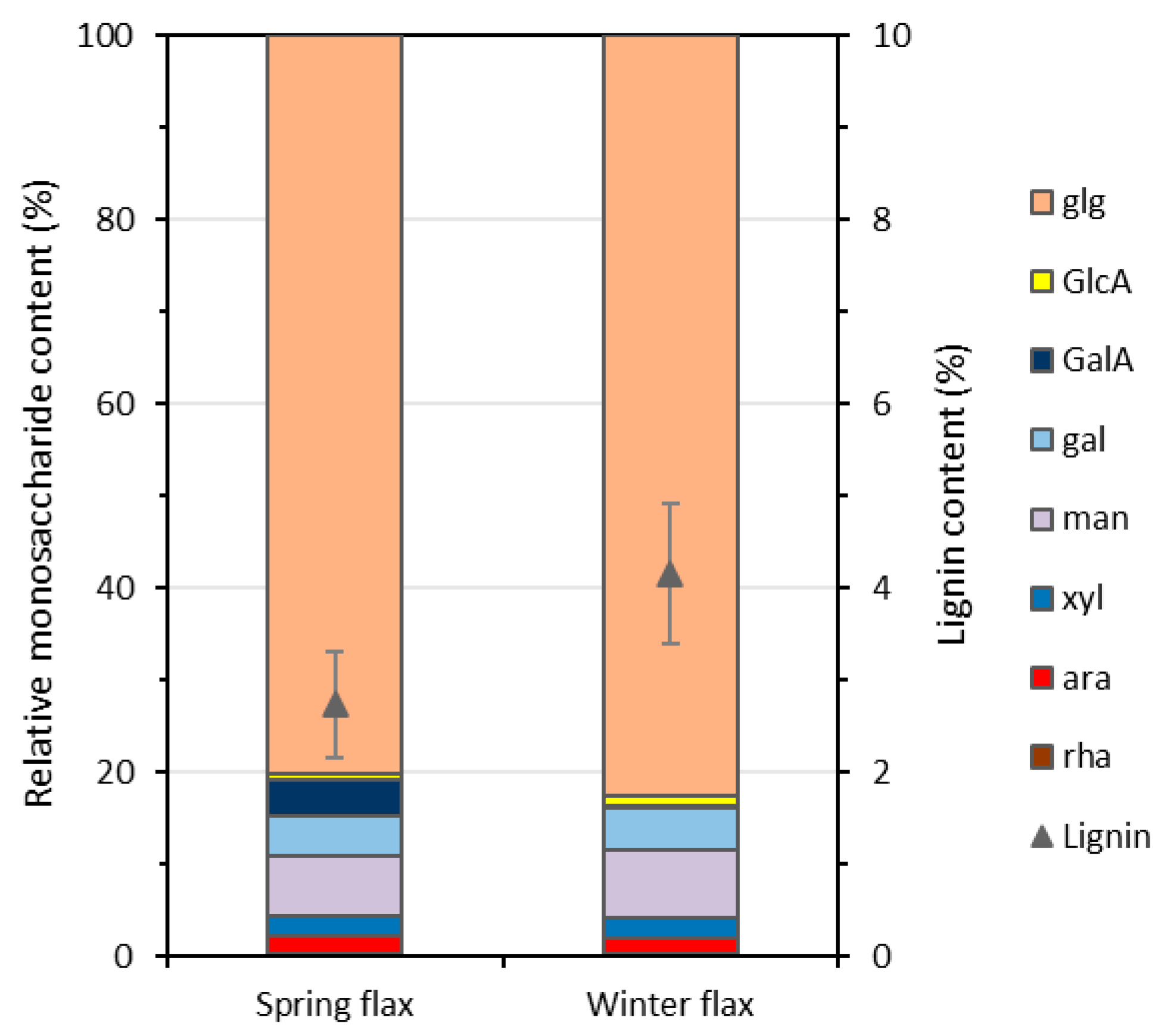

Monosaccharide analysis showed only one notable difference: the absence of galacturonic acid (GalA) in the scutched fibres from the winter crop, whereas GalA made up about 4% of the total monosaccharides in the spring crop fibres (

Figure 9). GalA is the main sugar in pectic compounds like homogalacturonans and rhamnogalacturonans, which are abundant in the middle lamella and primary cell walls [

37]. Its presence is typical immediately after harvesting and declines as retting progresses [

38]. Thus, its persistence in the spring crop indicates incomplete retting, while its near absence in the winter crop confirms more complete retting. These results suggest that the different growing conditions did not notably affect the final monosaccharide composition of the retted fibres.

The lignin content of flax fibres varies depending on plant maturity and growing conditions, but is generally very low—typically below 5% of dry matter [

39,

40], compared to 20–30% in softwoods and 10–15% in grass fibres [

33]. Here, Analysis revealed a lignin content of 2.74% in the Elixir spring crop and 4.15% in the winter crop (

Figure 9), representing over 50% more lignin.

Lignin is a complex phenolic polymer that strengthens cell walls and provides resistance to environmental stresses. It accumulates first in the middle lamellae and cell junctions before extending into secondary cell walls [

41]. Its synthesis is known to increase under abiotic stresses such as drought [

11,

13,

42] or cold [

43]. Although this effect is stronger in xylem than in bast fibres [

44], winter conditions can still promote hyperlignification in bast tissues.

In this study, the high lignin content observed in winter flax appears to be a response to low temperatures during the extended growth period, which allows prolonged lignin deposition. This pattern matches findings in other winter crops such as cereals [

45] and oilseed flax [

46].

Thioacidolysis analysis confirmed this pattern. In flax, lignin mainly consists of guaiacyl (G) units, with smaller amounts of syringyl (S) and negligible p-hydroxyphenyl (H) units [

41,

47].

Table 5 shows the yields of these monomers. Thioacidolysis cleaves the labile aryl-alkyl-ether linkages, thereby enabling the characterization of the so-called uncondensed lignin fraction. Total yields of labile linkages were very low, as reported previously [

47], indicating a relatively condensed lignin structure, with no significant differences between the winter crop and literature data. The low S/G ratio for winter crop (0.07) indicated a guaiacyl-rich lignin, typical of condensed lignin [

48]. Surprisingly, no G units were extracted from the spring crop, which instead contained mostly S units (0.09 ± 0.01 µmol g

−1 of dry matter)—a rare result suggesting a highly condensed lignin structure, most likely linked to drought stress.

In summary, the spring crop fibres showed a typical lignin content, but incomplete retting, as reflected by the higher GalA content. In contrast, the winter crop fibres were more lignified, with a lignin monomeric profile similar to that of spring flax grown under standard conditions. This increased lignification likely reflects a response to cold stress during winter and to the extended growth cycle. However, it complicates retting and scutching processes, resulting in poor separation of fibre bundles, ultimately posing challenges for downstream processes such as spinning.

3.7. Potential of Winter Flax and Other Adaptation Strategies to Climate Change

One adaptation strategy for coping with climate risks to spring-sown flax is shifting sowing to autumn. Winter flax is increasingly adopted for its agronomic advantages. By developing roots over winter, the crop can access deeper soil moisture in spring, improving its resilience to early-season drought. Winter flax also matures earlier, avoiding peak summer heat and spreading harvesting work over a longer period, which reduces pressure on processing facilities. However, there is only a narrow window—less than three months—between spring flax harvest and winter sowing, which complicates farm planning.

Despite these advantages, winter flax remains vulnerable. It is more susceptible to late-winter hazards like frost and waterlogging. While climate warming may reduce spring frosts, frost damage during regrowth can still be severe [

3]. For instance, although the 2023 winter flax harvest was excellent, the 2022 and 2024 crops suffered heavy frost and flooding damage. Establishment can also fail when heavy rain in autumn waterlogs soils. Additionally, winter flax usually requires more phytosanitary treatments, which conflicts with goals to reduce chemical inputs. Nevertheless, in case of winter crop failure, fields can be reploughed and sown with spring flax, limiting losses. From a quality perspective, winter flax fibres are generally lower in quality because of higher lignin content, as demonstrated earlier, which complicates fibre separation, resulting in prices 5–10% lower than spring flax.

Winter flax is therefore promising, especially in areas increasingly affected by spring droughts. However, its yield risks, processing challenges, and higher input needs mean it should complement, not fully replace, spring flax.

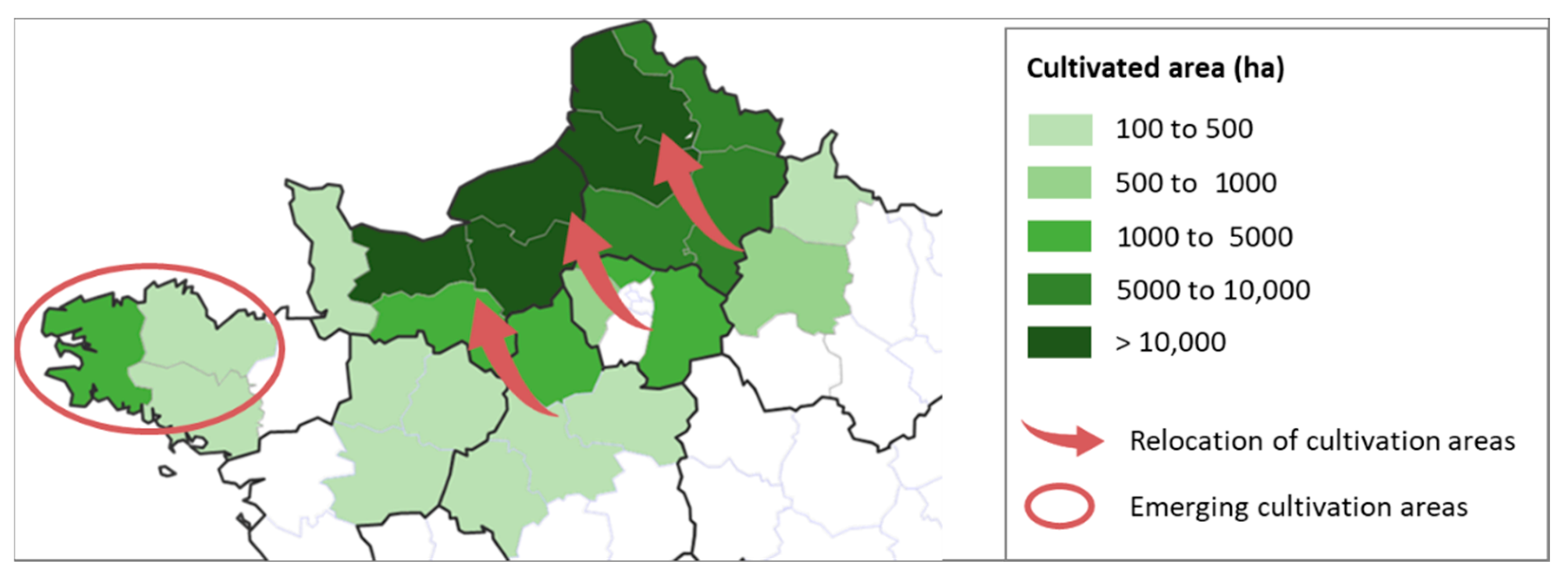

Geographically, climate change is also pushing flax cultivation closer to coastal regions with more temperate, stable climates [

49] (

Figure 10). Traditional inland growing areas are increasingly unsuitable due to heat and drought. At the same time, new regions are emerging as viable alternatives. For example, in the French Brittany region, flax area expanded from 600 ha in 2023 to 2500 ha in 2024, with 8000 ha targeted by 2030.

Additional climate adaptation strategies include varietal selection. Historically, breeding focused on improving yield, lodging, and disease resistance [

30]. Now, breeders also aim to develop spring varieties more tolerant to heat and drought and improve winter flax lines. However, breeding remains a slow process, requiring a decade or more to deliver new varieties.

Cropping practices are also evolving, with more attention to agroecological methods and conservation agriculture to maintain soil health, enhance biodiversity, and reduce inputs.

Despite high interannual yield variability—including poor harvests like 2023—flax cultivation continues to expand in Western Europe, covering about 200,000 ha in 2025—a 14% increase over 2024 [

50]. The crop’s strong economic returns—it can yield three to four times more revenue per hectare than wheat or rapeseed—are driving this growth. To keep this momentum and secure profitability, robust adaptation strategies are essential to stabilise yields and meet growing industrial demand for flax fibre.

4. Conclusions

Over four years (2021–2024) of spring cultivation of the Elixir flax variety, strong interannual climate variability—especially spring droughts—consistently reduced yields. Yet, the mechanical properties of elementary fibres remained stable. As these yield reductions become more frequent, winter flax crops are gaining traction as an adaptation strategy. To evaluate their potential and understand how winter conditions affect plant development, the Elixir spring flax variety was cultivated as both a spring and a winter crop in 2023—a year marked by a mild winter and an unusually dry spring. Despite the two crops were grown on different plots, and therefore on soils with potentially slightly different properties, contrasting weather conditions clearly dominated the plants’ responses. The winter crop benefitted from more favourable conditions overall. Stems were taller (>1 m) and thicker, while spring flax stems, stressed by drought, were shorter and thinner. Internally, the two crops showed similar stem structure, except for a thinner xylem in winter flax. The spring crop produced fewer fibres at mid-stem height due to water stress, but the mechanical properties of the elementary fibres remained comparable between the two crops. However, cell development temperature clearly affected fibre length: fibres in the lower part of the winter flax, grown during colder winter months, were shorter than those of the spring crop, which grew during warmer months, potentially making spinning more challenging. Biochemical analysis also showed higher lignin content in winter flax fibres—likely a response to cold stress—with important implications for industrial processing. Increased lignification makes retting, scutching, and fibre division for spinning more difficult. As a result, processing winter flax may require adjusted retting protocols, modifications of scutching parameters, or fibre sorting strategies to compensate for these structural differences.

Despite these challenges, this study showed that, under favourable climatic conditions, a spring variety can be successfully grown as a winter crop, producing fibres of comparable mechanical performance. Winter flax is therefore a promising option for adapting flax cultivation to climate change. However, its adoption must be supported by other measures, such as shifting cultivation to more suitable regions and breeding new varieties better suited to changing climates, to secure long-term resilience of flax production.

Further research should investigate more precisely how temperature affects elementary fibre elongation—ideally under controlled experimental conditions—and how lignin content evolves during the growth cycles of winter flax, to inform targeted improvements in both agronomy and processing.