Achieving High Hardness and Uniformity in Fe-Based Amorphous Coatings for Enhanced Wear Resistance via Explainable Machine Learning

Highlights

- •

- A unified HVAF process optimization framework is proposed by integrating DDPM-based data augmentation with explainable machine learning.

- •

- DDPM generates synthetic samples with the highest statistical fidelity and distributional consistency, effectively mitigating data scarcity.

- •

- The optimized GBR model, enhanced with 10% DDPM-generated data, achieves superior prediction accuracy and generalization for coating hardness and uniformity.

- •

- SHAP analysis quantitatively reveals the dominant effect of spraying distance and uncovers coupled mechanisms governing hardness uniformity.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

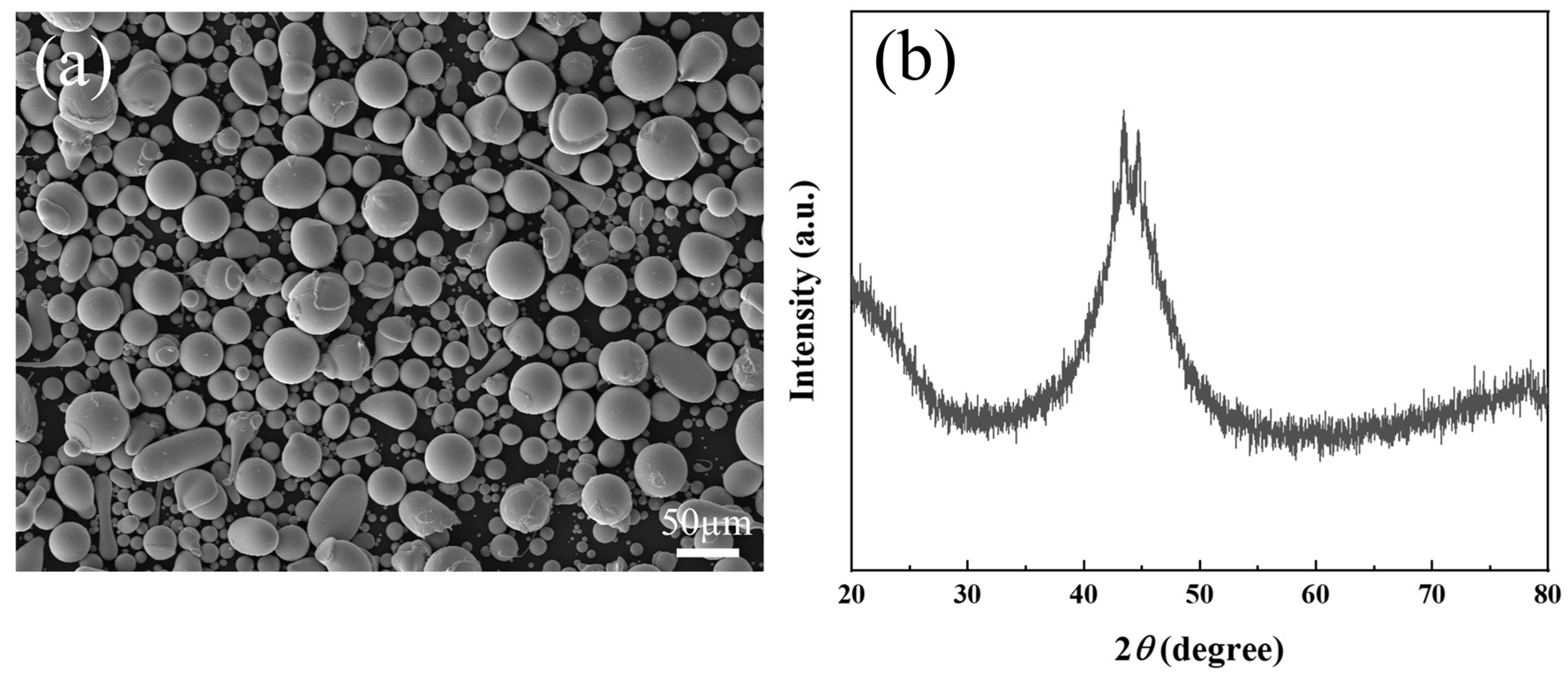

2.1. Spraying Materials

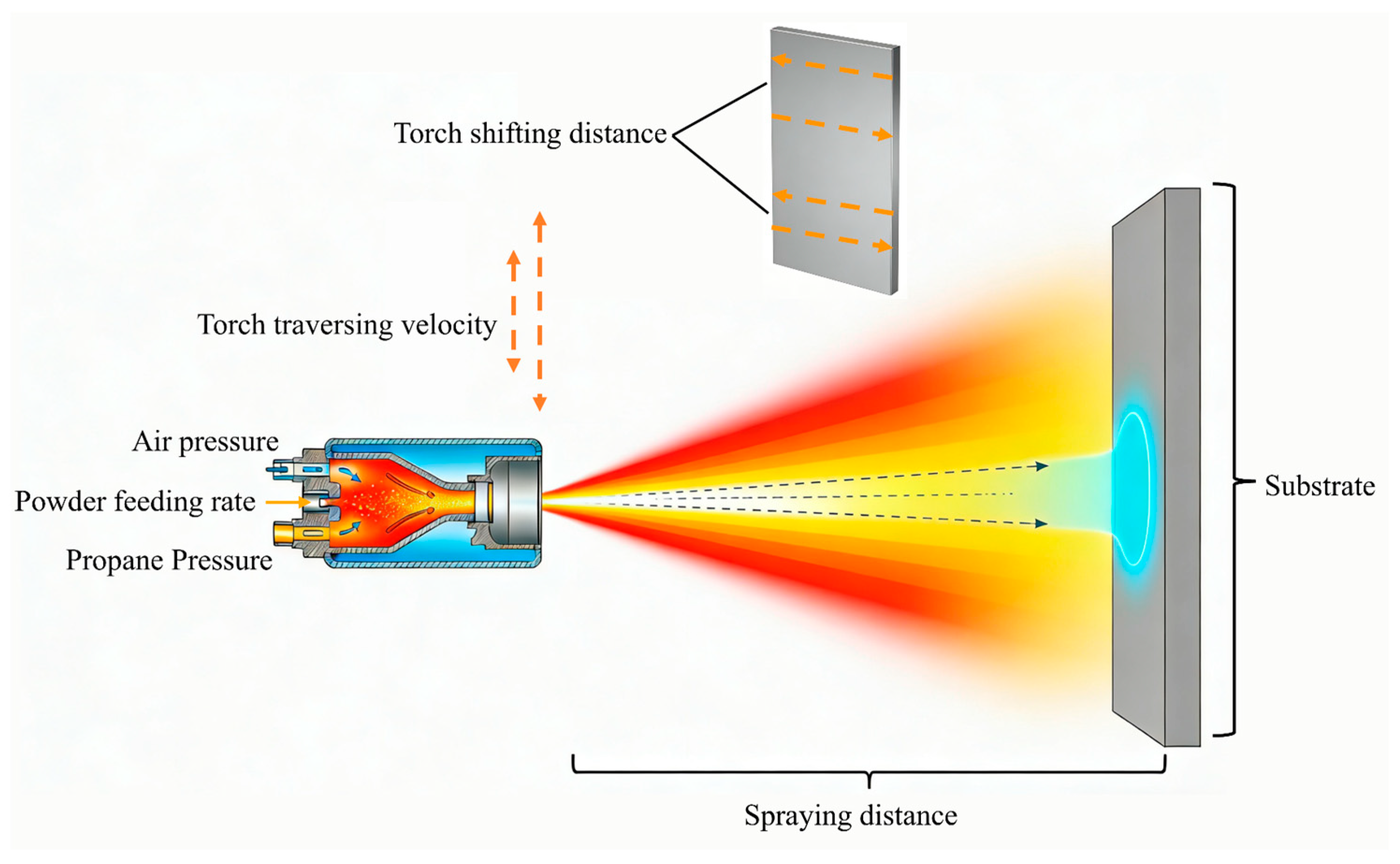

2.2. Coating Fabrication and Characterization

2.3. Data Preprocessing and Machine Learning Framework

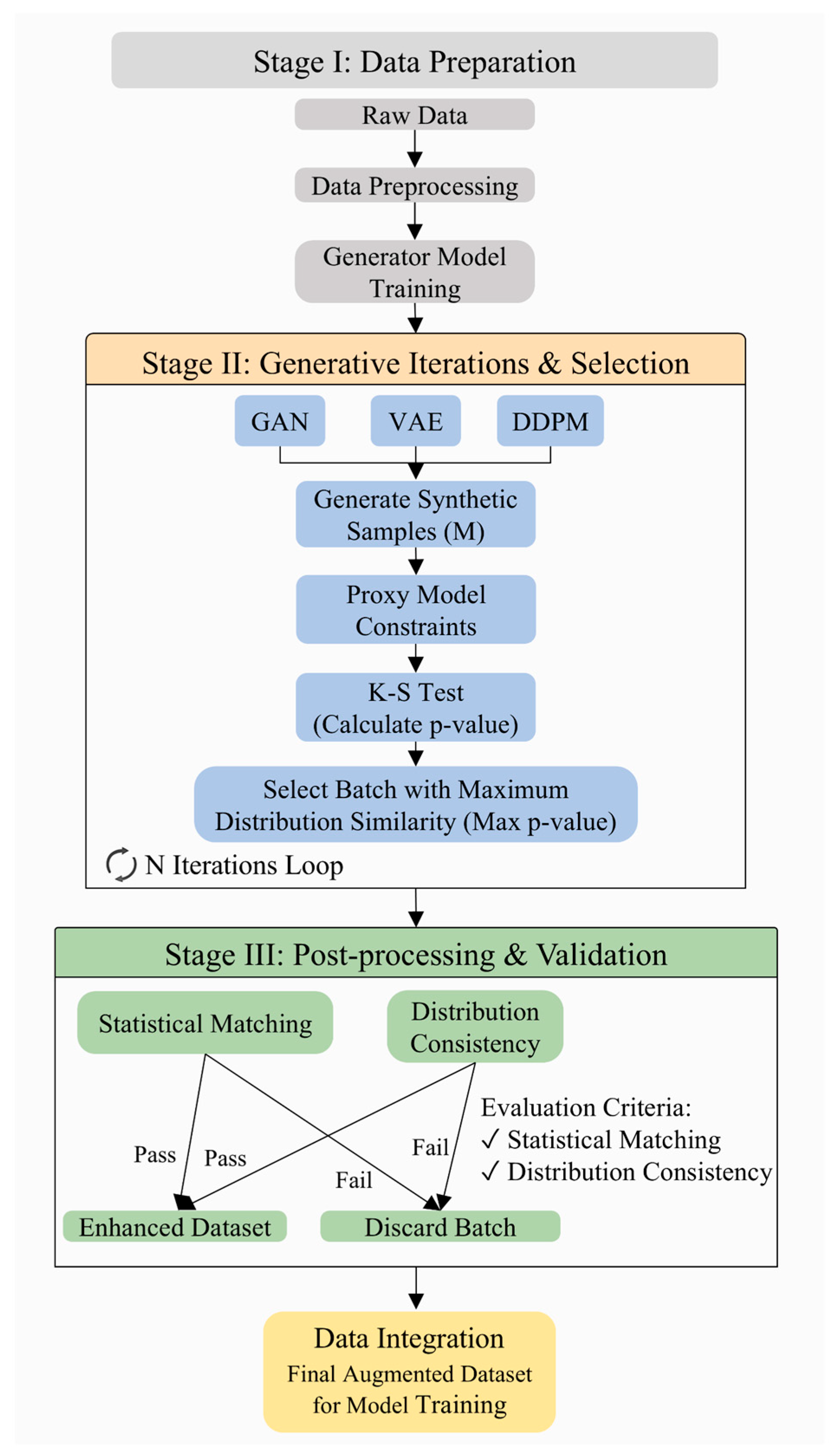

2.4. Deep Generative Models and Data Augmentation Strategy

2.5. Explainable Machine Learning Approach

3. Results and Discussion

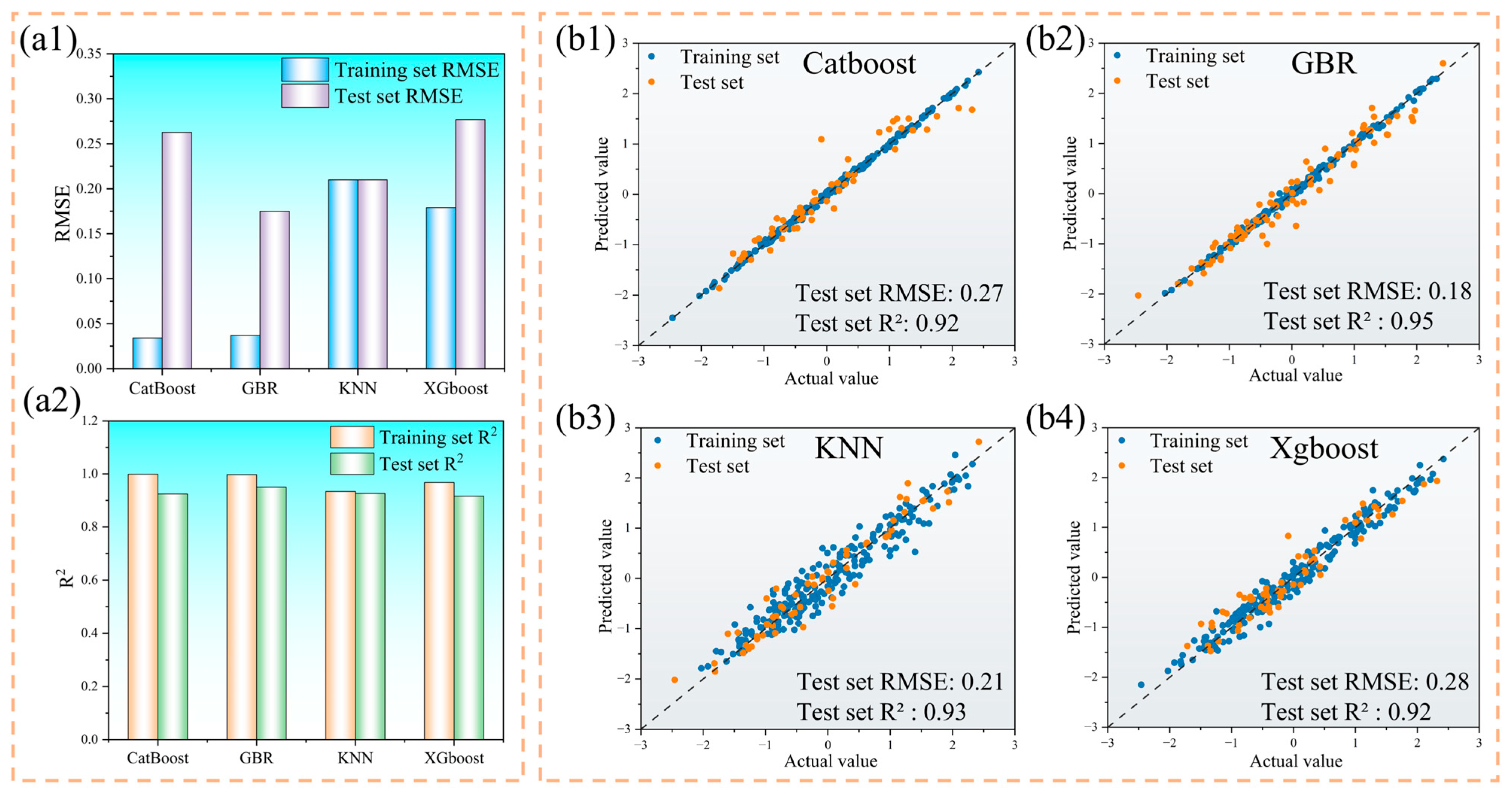

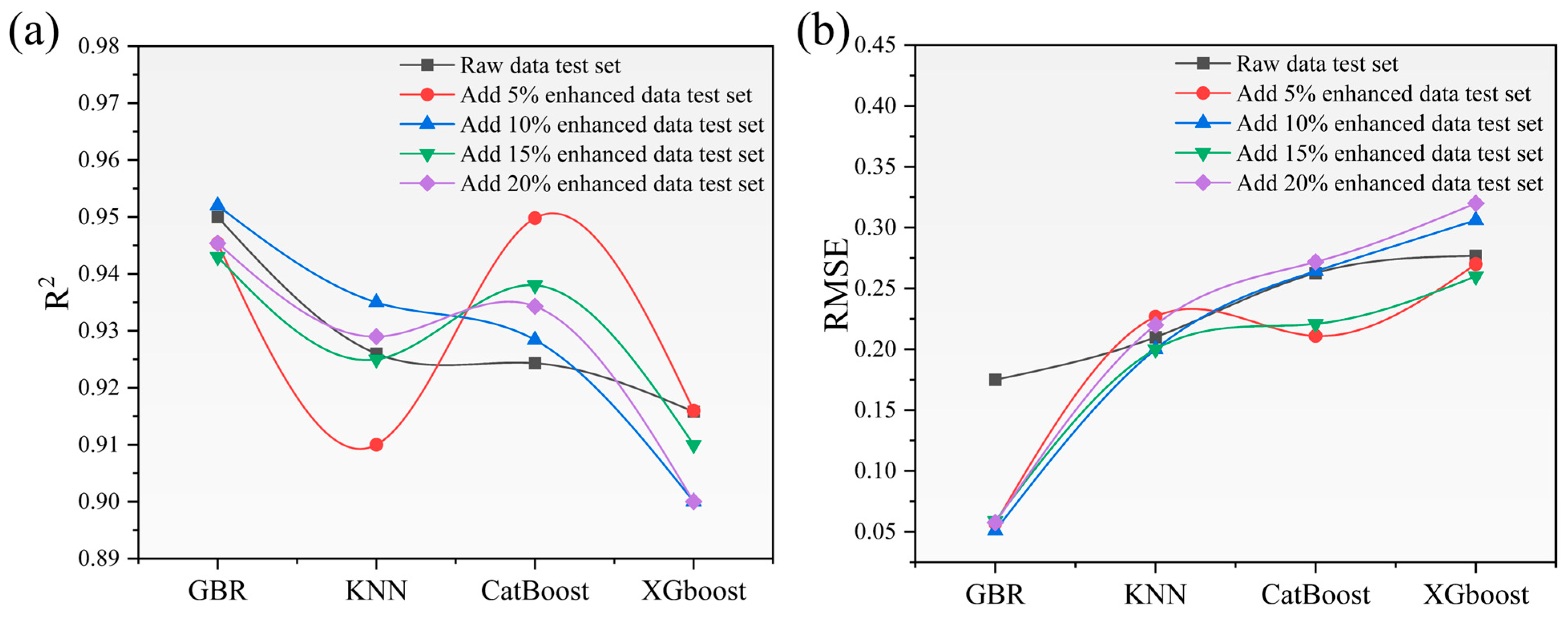

3.1. Comparison of Machine Learning Model Performance

3.2. Evaluation of Data Augmentation Models

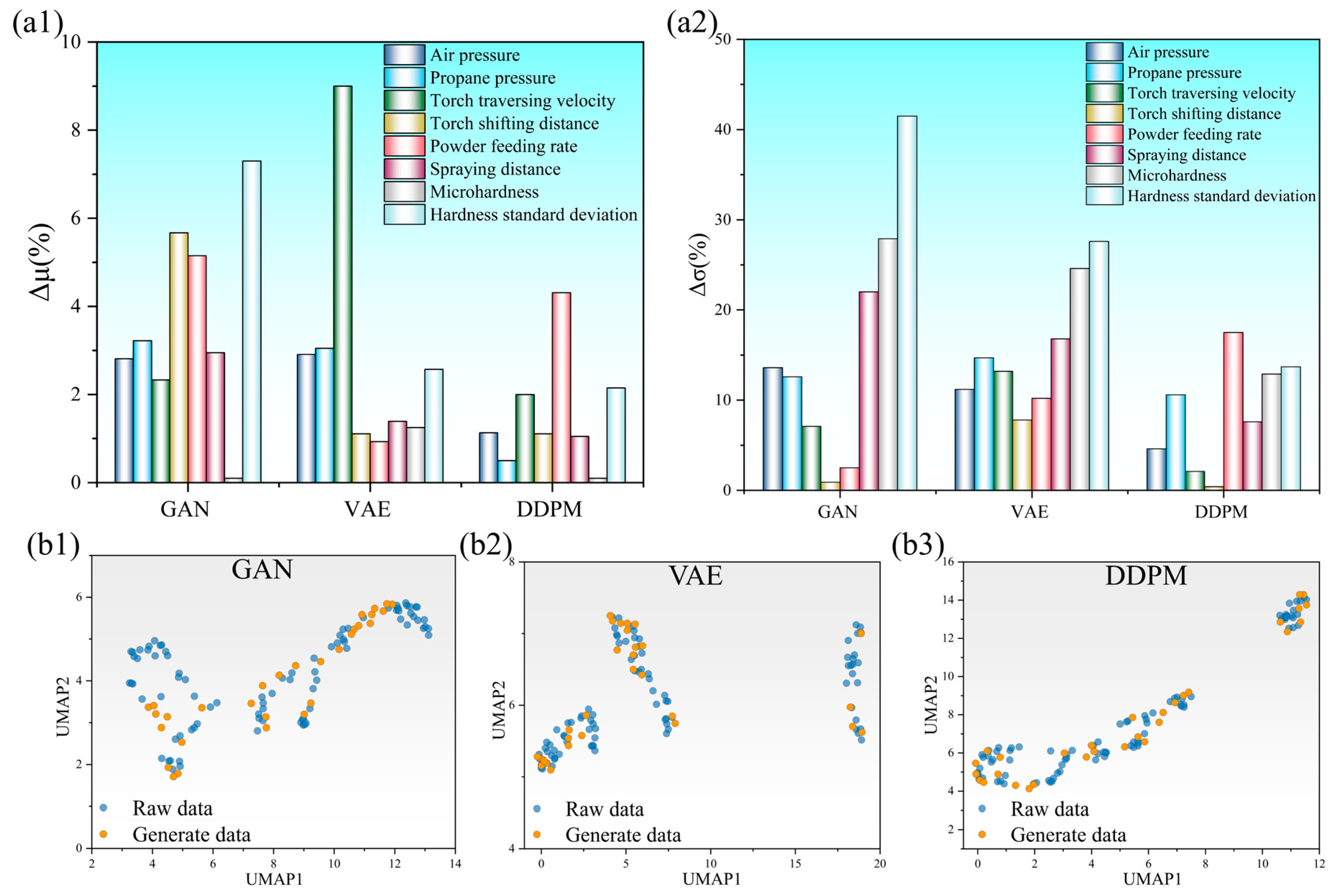

3.2.1. Selection of the Augmentation Model

3.2.2. Validation of Augmentation Model Performance

3.3. Model Interpretability Analysis

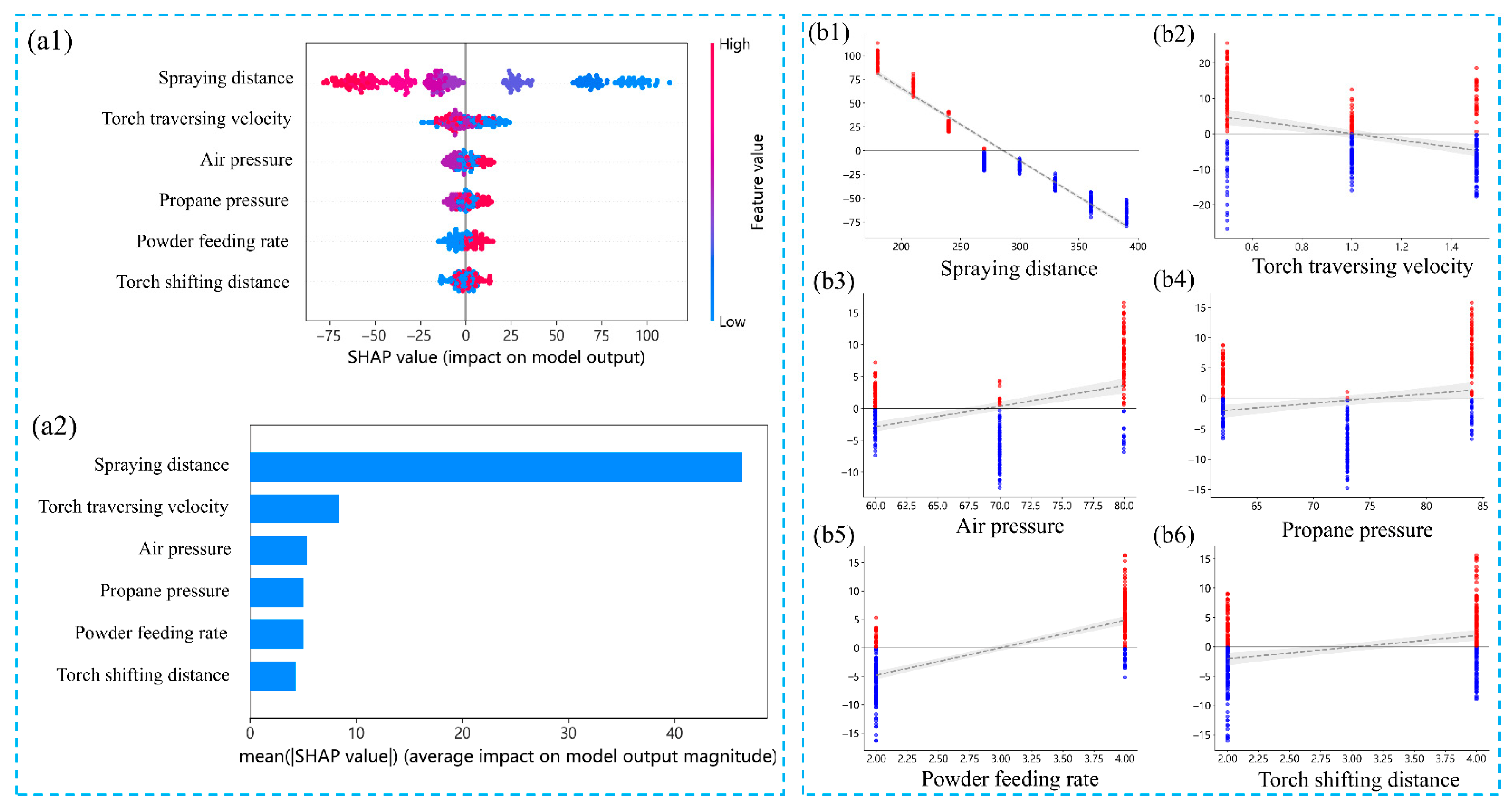

3.3.1. SHAP Analysis of Coating Microhardness

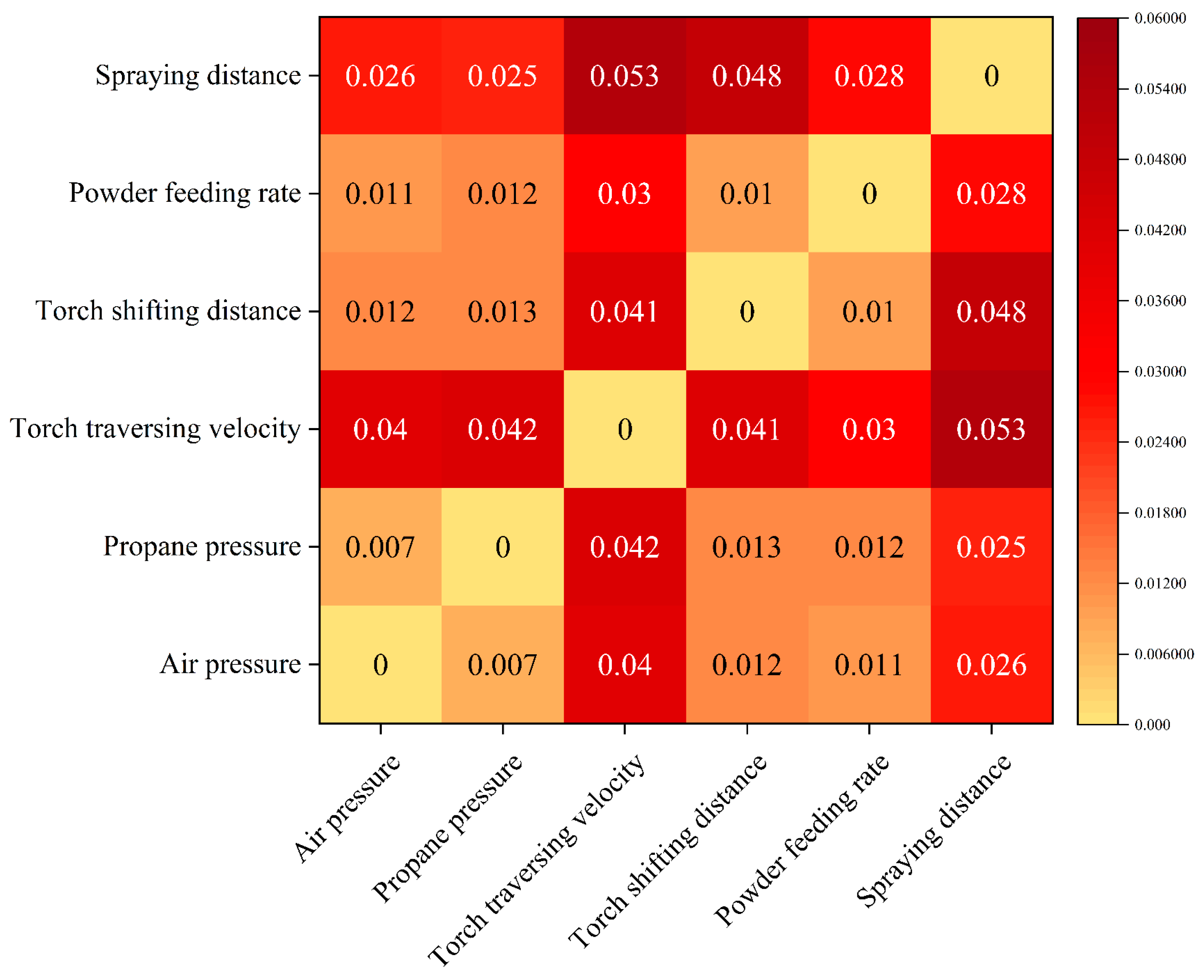

3.3.2. Analysis of Coating Microhardness Uniformity

3.4. Parameter Space Expansion and Screening

3.5. Comparative Evaluation of Friction and Wear Performance

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- A comprehensive comparison of three generative models—GAN, VAE, and DDPM—demonstrated that DDPM exhibits superior statistical fidelity and distribution consistency with respect to real HVAF process data, thereby effectively mitigating the limitations imposed by data scarcity. Among ten representative regression algorithms, GBR delivered the highest predictive accuracy and robustness. Furthermore, augmenting the training dataset with 10% DDPM-generated samples led to a further improvement in both prediction accuracy and model generalization.

- (2)

- SHAP-based feature importance and interaction analyses quantitatively revealed that spraying distance plays a dominant governing role in determining coating microhardness, substantially outweighing the contributions of other process parameters. In contrast, hardness uniformity is jointly regulated by the coupled effects of torch traversing velocity, torch shifting distance, and powder feeding rate. These findings not only enhance the transparency and interpretability of the predictive models but also provide mechanism-informed guidance directly applicable to engineering-oriented process optimization.

- (3)

- By interpolatively expanding the original process parameter space and implementing a two-stage screening strategy, 98 high-potential process parameter combinations were identified. Experimental validation confirmed that the optimal parameter set simultaneously achieved a hardness level exceeding the maximum value observed in the original experimental dataset and improved hardness uniformity, resulting in a 13.6% reduction in wear rate compared with the reference condition. These results verify the effectiveness, robustness, and practical feasibility of the proposed framework in advancing process-window optimization and enhancing the performance of HVAF-sprayed Fe-based amorphous coatings.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, R.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Q.; Yang, Y.; Li, N.; Liu, L. Study of structure and corrosion resistance of Fe-based amorphous coatings prepared by HVAF and HVOF. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 2351–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, L.; Pukasiewicz, A.; de Aguiar, D.; Zara, A.; Björklund, S. Study of the corrosion and cavitation resistance of HVOF and HVAF FeCrMnSiNi and FeCrMnSiB coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 374, 910–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Zhang, Z.; Jing, Z.; Yuan, J.; Ma, C.; Yan, S.; Zhang, S.; Liang, X. Research Progress on Process Optimization of Thermal-Sprayed Iron-Based Amorphous Coatings. Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 2025, 14, 247–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Christofides, P.D. Modeling and analysis of HVOF thermal spray process accounting for powder size distribution. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2003, 58, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksa, M.; Turunen, E.; Suhonen, T.; Varis, T.; Hannula, S.-P. Optimization and Characterization of High Velocity Oxy-fuel Sprayed Coatings: Techniques, Materials, and Applications. Coatings 2011, 1, 17–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Yuan, J.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Z.; Jing, Z.; Chu, Z.; Liang, X. Innovative preparation and corrosion resistance of Fe-based amorphous coatings fabricated by ultra short pulse laser manufacturing process. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1049, 185410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgenc, T.; Altay, O.; Ulas, M.; Ozel, C. Extreme learning machine and support vector regression wear loss predictions for magnesium alloys coated using various spray coating methods. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 127, 185103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ling, C. A strategy to apply machine learning to small datasets in materials science. npj Comput. Mater. 2018, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, A.; Lagerquist, R.; Gagne, D.J.; Jergensen, G.E.; Elmore, K.L.; Homeyer, C.R.; Smith, T. Making the Black Box More Transparent: Understanding the Physical Implications of Machine Learning. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2019, 100, 2175–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; Liao, H.; Deng, S. Prediction and analysis of high velocity oxy fuel (HVOF) sprayed coating using artificial neural network. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 378, 124988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paturi, U.M.R.; Cheruku, S.; Geereddy, S.R. Process modeling and parameter optimization of surface coatings using artificial neural networks (ANNs): State-of-the-art review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 38, 2764–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Wang, W.; Su, Y.; Qi, W.; Feng, L.; Xie, L. Prediction of HVAF thermal spraying parameters and coating properties based on improved WOA-ANN method. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 109265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yu, Z.; Wu, H.; Liao, H.; Zhu, Q.; Deng, S. Implementation of Artificial Neural Networks for Forecasting the HVOF Spray Process and HVOF Sprayed Coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2021, 30, 1329–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, S.; Di, J.; Zhao, T.; Fan, H.; Ning, Z.; Sun, J.; Huang, Y. Multi-Objective Optimization of HVAF-Sprayed Fe-Based Amorphous Alloy Coatings via Machine Learning for Superior Corrosion Resistance. Corros. Sci. 2025, 256, 113225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Gao, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, D.; Yang, B.; Sun, W.; Wang, J. Achieving superior corrosion resistance in HVAF-sprayed Fe-based amorphous alloy coatings through data-driven machine learning. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 247, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Xia, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; He, C.; Chen, D.; Jiang, B. PCS: Property-composition-structure chain in Mg-Nd alloys through integrating sigmoid fitting and conditional generative adversarial network modeling. Scr. Mater. 2025, 265, 116762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Qin, X.; Xia, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Huang, W.; Song, Y.; Tang, W.; Chen, D. Interpretable machine learning excavates a low-alloyed magnesium alloy with strength-ductility synergy based on data augmentation and reconstruction. J. Magnes. Alloys 2025, 13, 2866–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdon, C.; Karimi, A.; Martin, J.-L. A study of high velocity oxy-fuel thermally sprayed tungsten carbide based coatings. Part 1: Microstructures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1998, 246, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E384-22; Standard Test Method for Microindentation Hardness of Materials. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Sharma, N.; Malviya, L.; Jadhav, A.; Lalwani, P. A hybrid deep neural net learning model for predicting Coronary Heart Disease using Randomized Search Cross-Validation Optimization. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 9, 100331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Wang, P.; Yan, R. Generative adversarial networks for data augmentation in machine fault diagnosis. Comput. Ind. 2019, 106, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadebec, C.; Thibeau-Sutre, E.; Burgos, N.; Allassonnière, S. Data Augmentation in High Dimensional Low Sample Size Setting Using a Geometry-Based Variational Autoencoder. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 45, 2879–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Wu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, A.; Qian, R.; Chen, X. Data Augmentation for Seizure Prediction with Generative Diffusion Model. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2024, 17, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzante, J.R. Testing for differences between two distributions in the presence of serial correlation using the Kolmogorov–Smirnovand Kuiper’s tests. Int. J. Clim. 2021, 41, 6314–6323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liang, Q.; Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Feature selection strategies: A comparative analysis of SHAP-value and importance-based methods. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Wang, X.; Lyu, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Heinen, E.; Sun, Z. Understanding cycling distance according to the prediction of the XGBoost and the interpretation of SHAP: A non-linear and interaction effect analysis. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 103, 103414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, G.; Martino, C.; Rahman, G.; Gonzalez, A.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Mishne, G.; Knight, R. Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) Reveals Composite Patterns and Resolves Visualization Artifacts in Microbiome Data. mSystems 2021, 6, e0069121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkina, A.C.; Ciccolella, C.O.; Anno, R.; Halpert, R.; Spidlen, J.; Snyder-Cappione, J.E. Automated optimized parameters for T-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding improve visualization and analysis of large datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Networks. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girin, L.; Leglaive, S.; Bie, X.; Diard, J.; Hueber, T.; Alameda-Pineda, X. Dynamical Variational Autoencoders: A Comprehensive Review. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 2022, 15, 1–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alblwi, A.; Makkawy, S.; Barner, K.E. D-DDPM: Deep Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models for Lesion Segmentation and Data Generation in Ultrasound Imaging. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 41194–41209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Li, C.; Huang, J.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Fu, B. ReF-DDPM: A novel DDPM-based data augmentation method for imbalanced rolling bearing fault diagnosis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 251, 110343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumuni, A.; Mumuni, F. Data augmentation: A comprehensive survey of modern approaches. Array 2022, 16, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.-T.; Tran, V.-H.; Nguyen, N.-B.; Nguyen, T.-K.; Cheung, N.-M. On Data Augmentation for GAN Training. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 1882–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, J.; Chen, X. Machine Learning-Based Prediction of High-Entropy Alloy Hardness: Design and Experimental Validation of Superior Hardness. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2024, 77, 3973–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauer, G.; Rauwald, K.-H.; Sohn, Y.J.; Vaßen, R. The Potential of High-Velocity Air-Fuel Spraying (HVAF) to Manufacture Bond Coats for Thermal Barrier Coating Systems. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2023, 33, 746–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobzin, K.; Zhao, L.; Heinemann, H.; Burbaum, E. Influence of the atmospheric plasma spraying parameters on the coating structure and the deposition efficiency of silicon powder. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 123, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, K.; Gangolu, S.; Antony, J.M. Effects of HVOF spray parameters on porosity and hardness of 316L SS coated Mg AZ80 alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 448, 128898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katranidis, V.; Kamnis, S.; Allcock, B.; Gu, S. Effects and Interplays of Spray Angle and Stand-off Distance on the Sliding Wear Behavior of HVOF WC-17Co Coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2019, 28, 514–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumeh, G.; Shahrooz, S.; Mahmood, G.; Ahmad, S.E. Investigation of stand-off distance effect on structure, adhesion and hardness of copper coatings obtained by the APS technique. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 2018, 12, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Awadi, G.A. Review of effective techniques for surface engineering material modification for a variety of applications. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2023, 10, 652–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, K.; Lian, G.; Zeng, J.; Chen, C.; Lan, R.; Kong, L. An investigation on graphite behavior and coating properties in the molten pool based on different powder particle sizes. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauer, G.; Rauwald, K.-H.; Sohn, Y.J.; Weirich, T.E. Cold Gas Spraying of Nickel-Titanium Coatings for Protection Against Cavitation. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2020, 30, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, W.; Hagen, L.; Luo, W. Process Parameter Settings and Their Effect on Residual Stresses in WC/W2C Reinforced Iron-Based Arc Sprayed Coatings. Coatings 2017, 7, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Chen, C.; Planche, M.-P.; Deng, S.; Huang, R.; Ren, Z.; Liao, H. Strengthened Peening Effect on Metallurgical Bonding Formation in Cold Spray Additive Manufacturing. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2019, 28, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, D.; Gao, H.; Han, X. Numerical analysis of the activated combustion high-velocity air-fuel (AC-HVAF) thermal spray process: A survey on the parameters of operation and nozzle geometry. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 405, 126588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoutam, A.K.; Lamana, M.S.; de Castilho, B.C.N.M.; Ben Ettouil, F.; Chandrakar, R.; Bessette, S.; Brodusch, N.; Gauvin, R.; Dolatabadi, A.; Moreau, C. The Role of HVAF Nozzle Design and Process Parameters on In-Flight Particle Oxidation and Microstructure of NiCoCrAlY Coatings. Coatings 2025, 15, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Leave | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Air pressure (psi) | 3 | 60, 70, 80 |

| Propane pressure (psi) | 3 | 62, 73, 84 |

| Torch traversing velocity (m/s) | 3 | 0.5, 1, 1.5 |

| Torch shifting distance (mm) | 2 | 2, 4 |

| Powder feeding rate (r/min) | 2 | 2, 4 |

| Spraying distance (mm) | 8 | 180, 210, 240, 270, 300, 330, 360, 390 |

| Parameter | Leave | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Air pressure (psi) | 5 | 60, 65, 70, 75, 80 |

| Propane pressure (psi) | 5 | 62, 67, 73, 78, 84 |

| Torch traversing velocity (m/s) | 5 | 0.5, 0.8, 1, 1.3, 1.5 |

| Torch shifting distance (mm) | 5 | 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4 |

| Powder feeding rate (r/min) | 5 | 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4 |

| Spraying distance (mm) | 15 | 180, 195, 210, 225, 240, 255, 270, 285, 300, 315, 330, 345, 360, 375, 390 |

| Sample | A | B | C | D | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted optimal parameter | Predicting Moderate Parameters | Predicted poor parameter | Optimal parameters of the dataset | ||

| Air pressure (psi) | 80 | 65 | 70 | 70 | 80 |

| Propane pressure (psi) | 84 | 67 | 73 | 73 | 84 |

| Torch traversing velocity (m/s) | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.8 | 1.5 |

| Torch shifting distance (mm) | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Powder feeding rate (r/min) | 4 | 2 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 4 |

| Spraying distance (mm) | 195 | 225 | 240 | 255 | 210 |

| Predicted microhardness (HV) | 1268.92 | 1124.54 | 1010.12 | 994.15 | 1165.13 |

| Predicted microhardness standard deviation (HV) | 79.49 | 115.4 | 125.07 | 110.79 | 89.69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, E.; Ma, C.; Yuan, J.; Yan, S.; Zhang, Z.; Jing, Z.; Zhang, B. Achieving High Hardness and Uniformity in Fe-Based Amorphous Coatings for Enhanced Wear Resistance via Explainable Machine Learning. Coatings 2026, 16, 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020199

Zhang E, Ma C, Yuan J, Yan S, Zhang Z, Jing Z, Zhang B. Achieving High Hardness and Uniformity in Fe-Based Amorphous Coatings for Enhanced Wear Resistance via Explainable Machine Learning. Coatings. 2026; 16(2):199. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020199

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Enhao, Cong Ma, Jiachi Yuan, Shuang Yan, Zhibin Zhang, Zhiyuan Jing, and Binbin Zhang. 2026. "Achieving High Hardness and Uniformity in Fe-Based Amorphous Coatings for Enhanced Wear Resistance via Explainable Machine Learning" Coatings 16, no. 2: 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020199

APA StyleZhang, E., Ma, C., Yuan, J., Yan, S., Zhang, Z., Jing, Z., & Zhang, B. (2026). Achieving High Hardness and Uniformity in Fe-Based Amorphous Coatings for Enhanced Wear Resistance via Explainable Machine Learning. Coatings, 16(2), 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020199