Effect of Copper Powder Modification and Silver Content on Coating Adhesion and Corrosion Resistance of Silver-Coated Copper Powder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiment

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Copper Powder Pretreatment and Surface Modification

- AlkalineCleaning Treatment

- 2.

- Acid pickling treatment

- 3.

- Surface Modification

2.3. Chemical Silver Plating

2.4. Performance Testing and Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

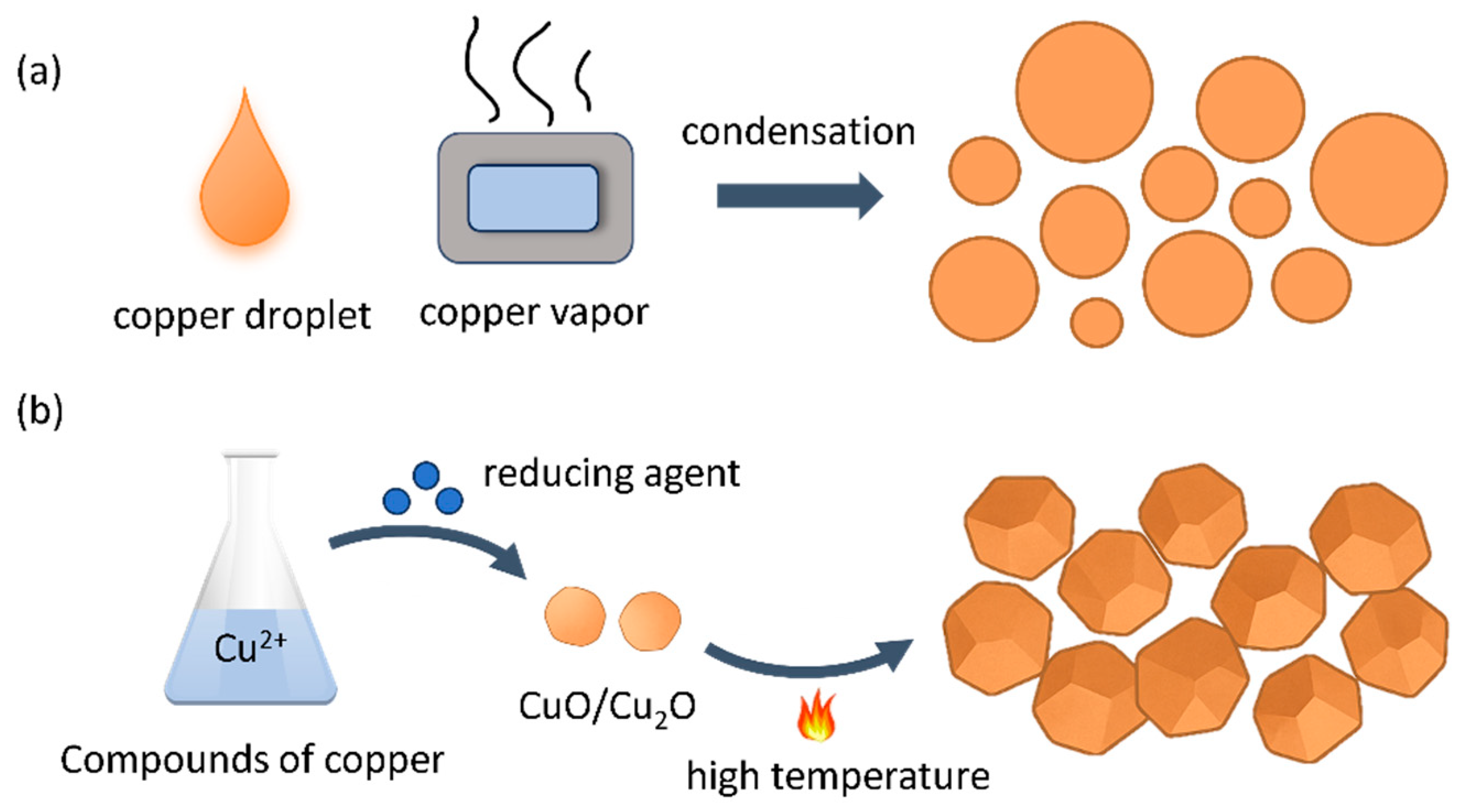

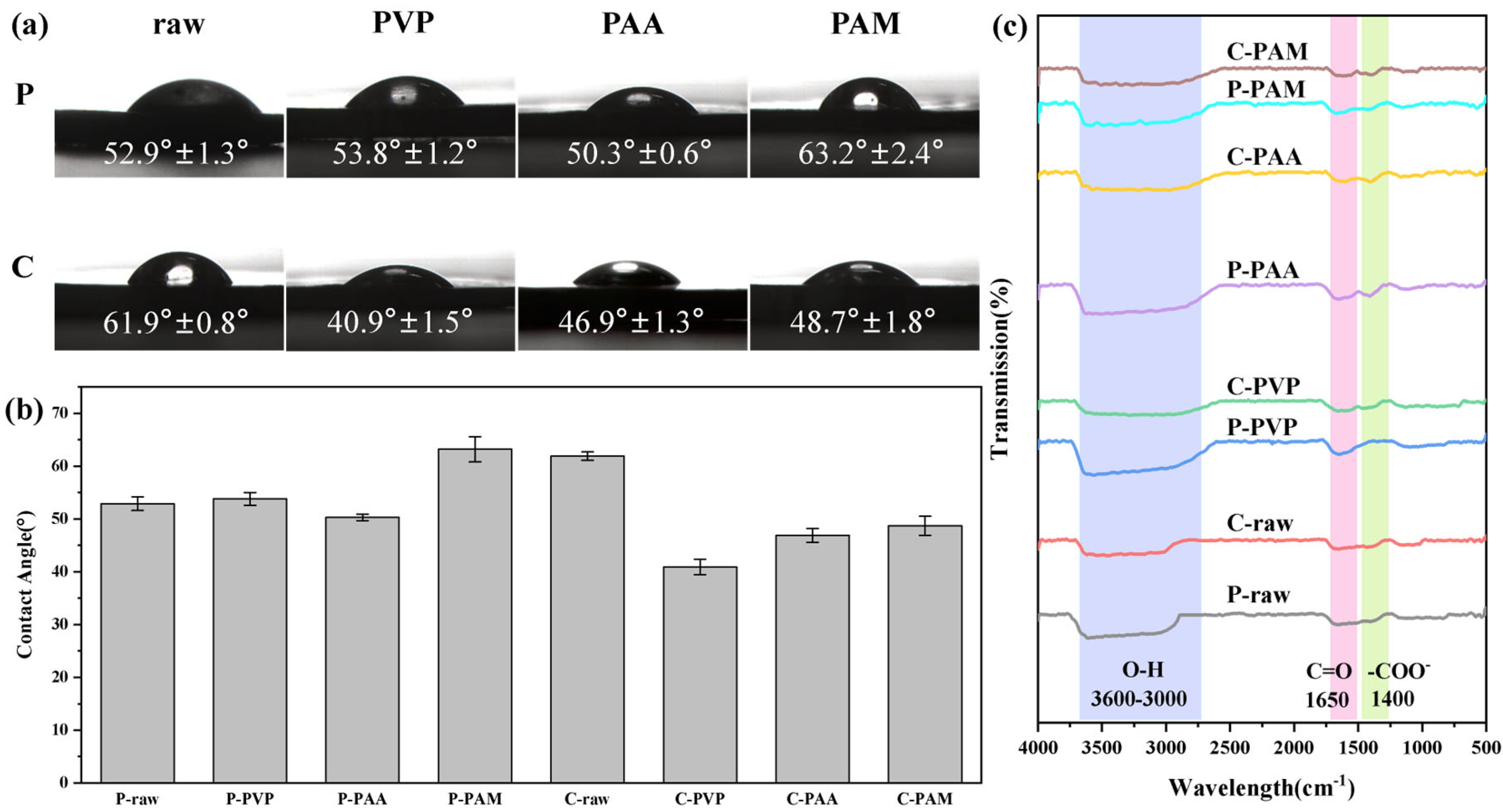

3.1. Optimization and Control of Surface Properties Through Copper Powder Modification

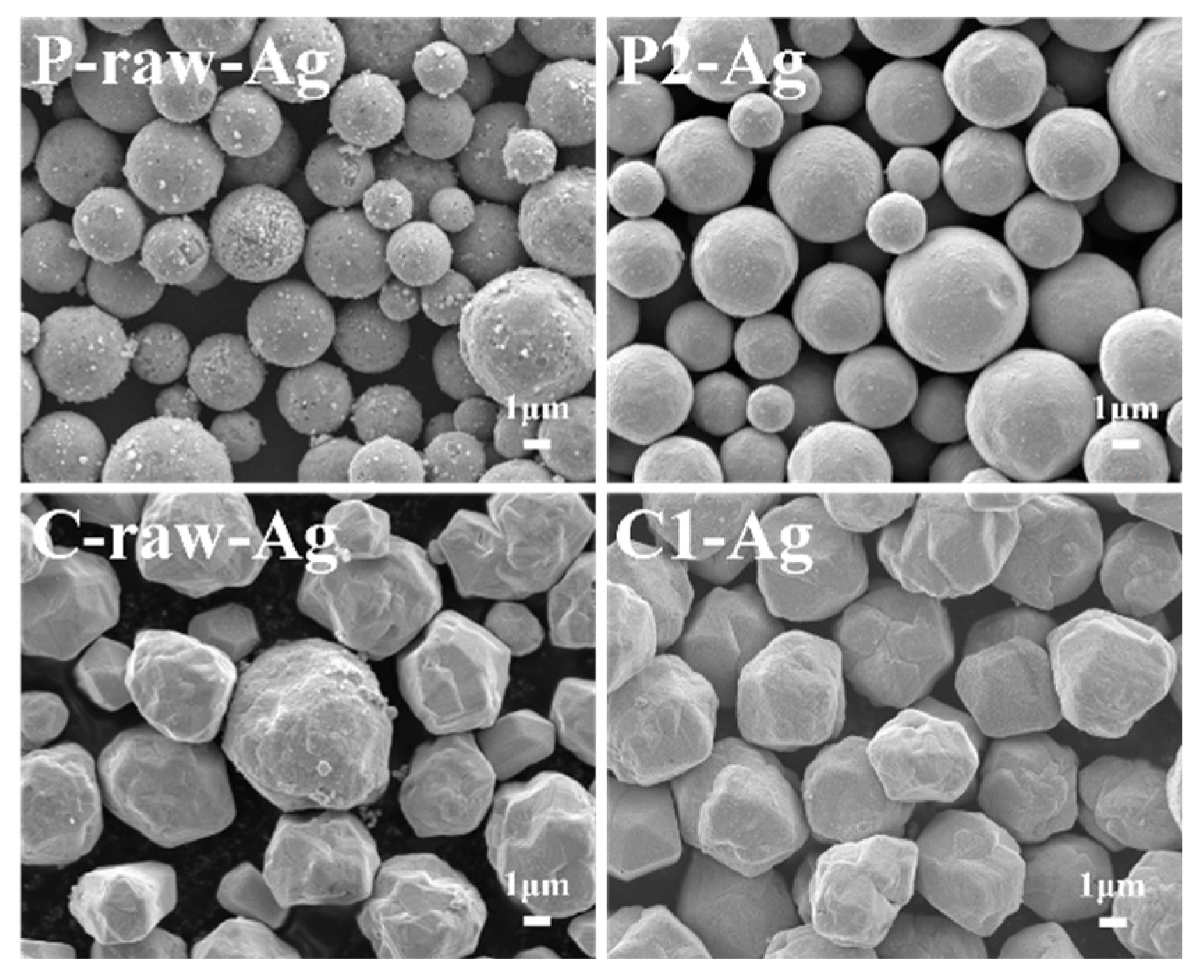

3.2. Effect of Copper Powder Surface Modification on the Plating Layer

3.3. Effect of Silver Content on the Properties of Silver-Plated Copper Powder

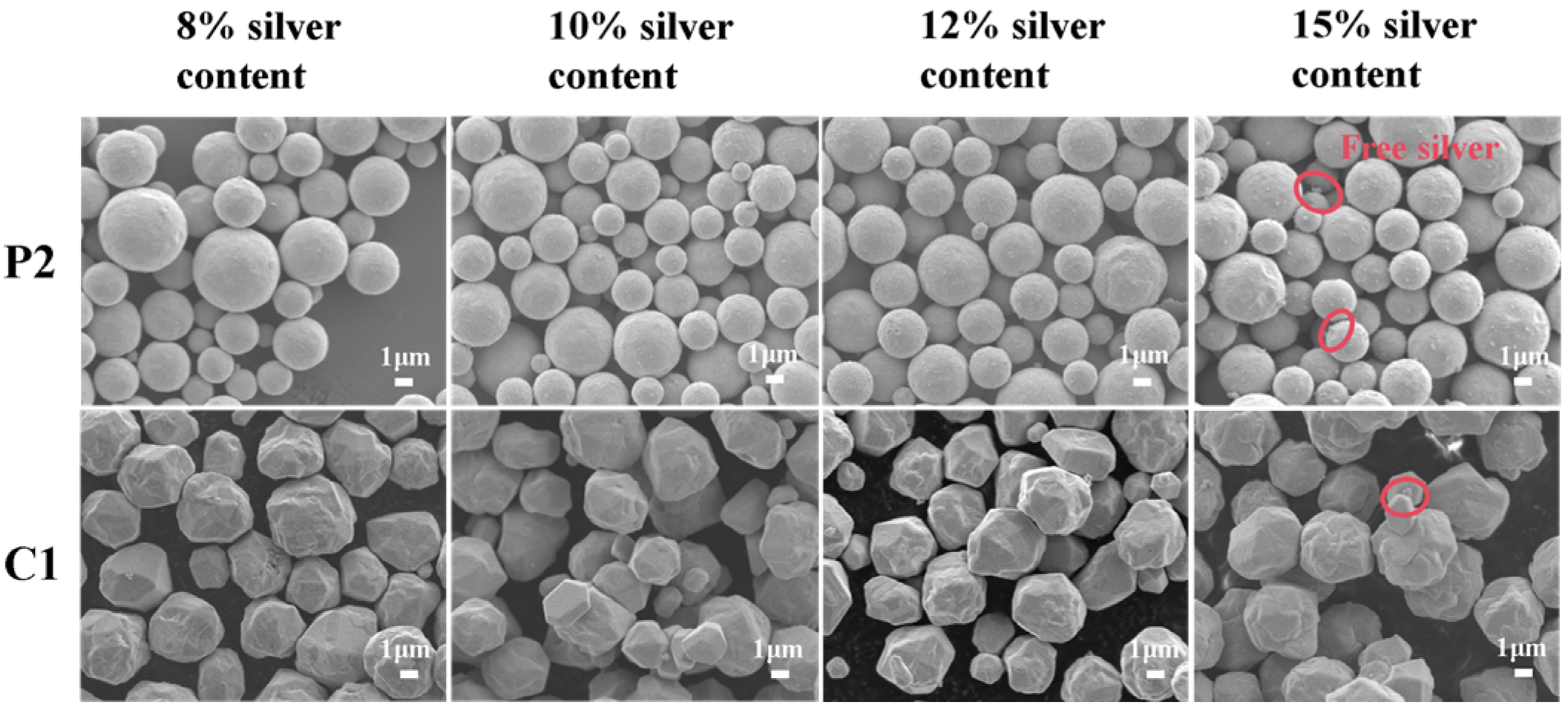

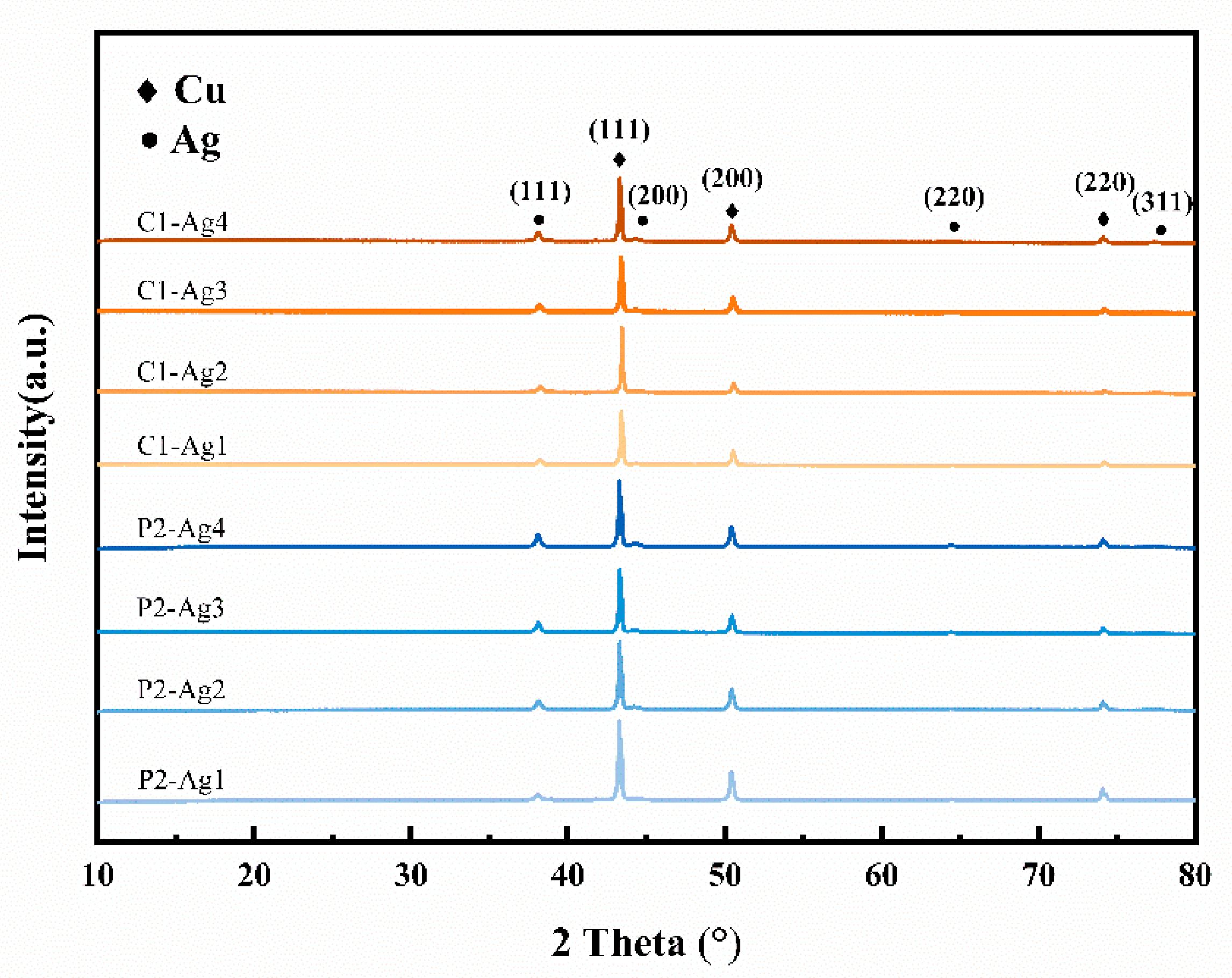

3.3.1. Morphology and Structure of Silver-Plated Copper Powder

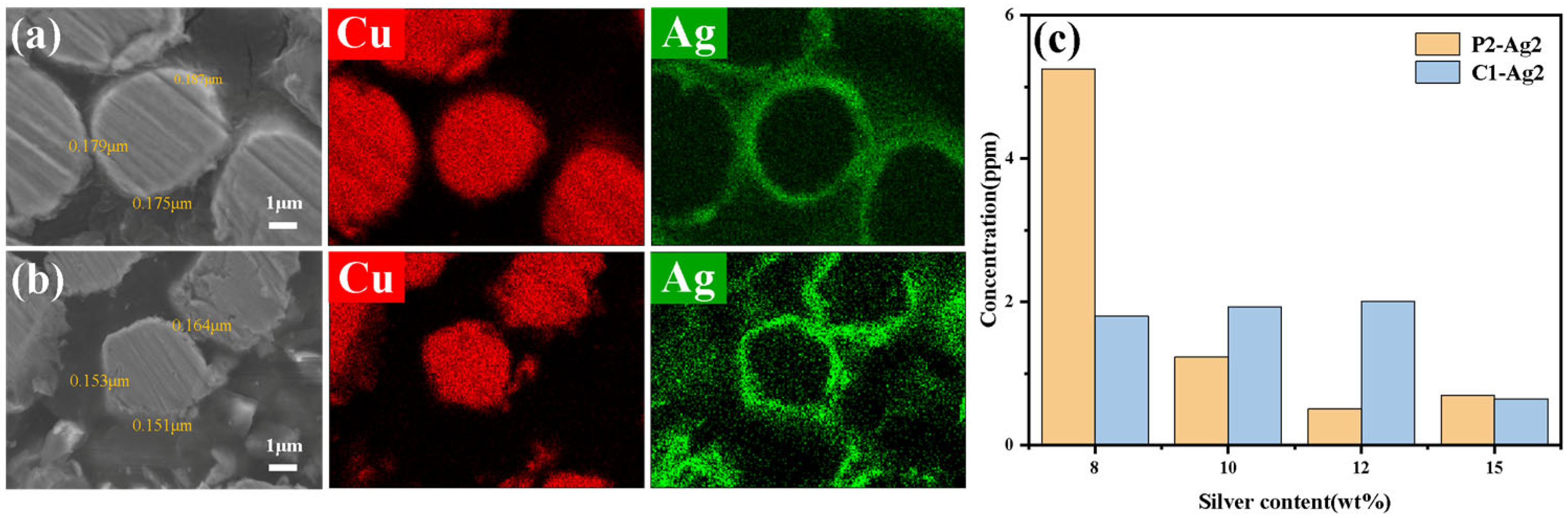

3.3.2. Envelopment and Compactness

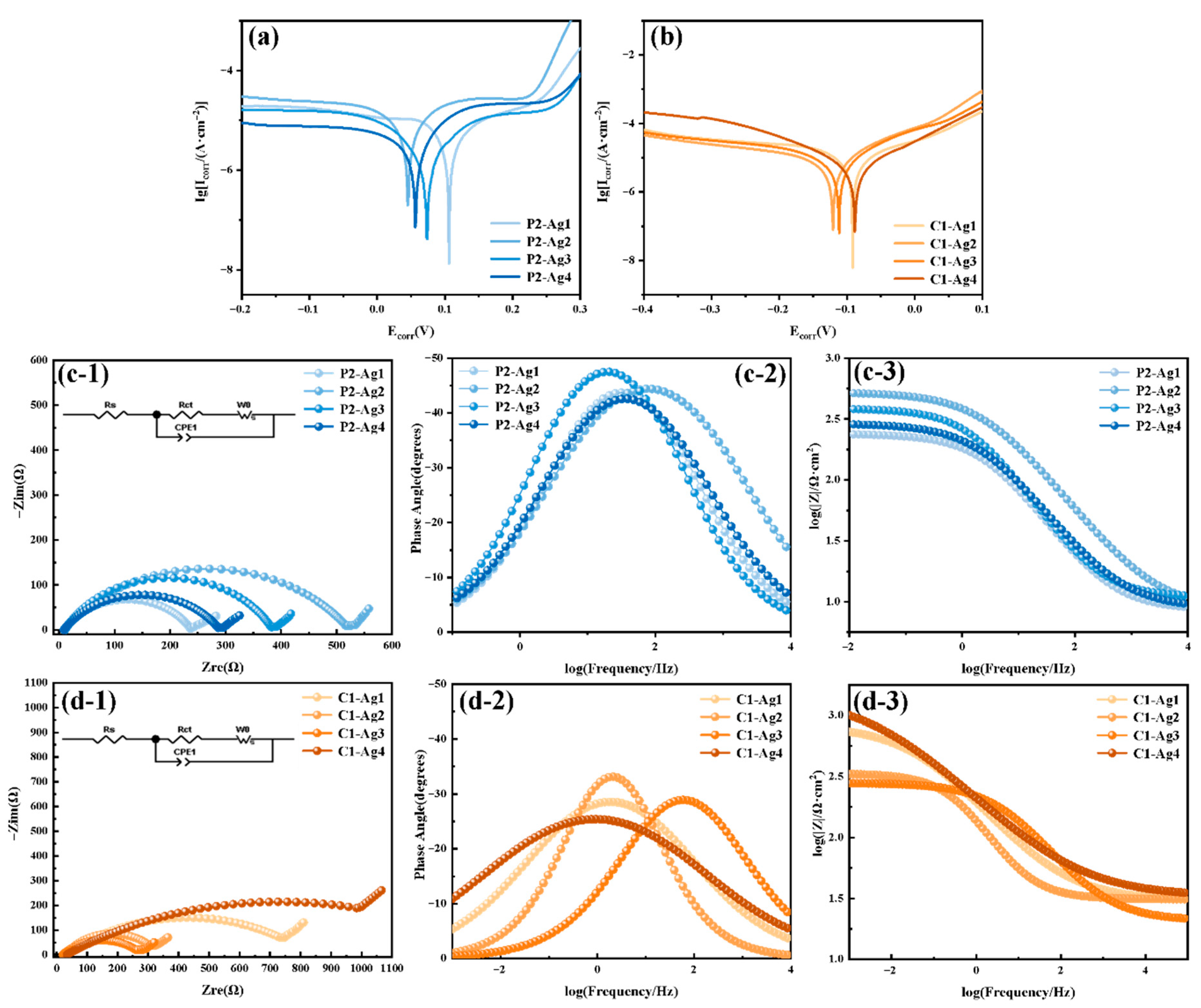

3.3.3. Corrosion Resistance

4. Conclusions

- The preparation method and surface characteristics of copper powder significantly influence the deposition behavior of silver layers during the silver plating process. Surface modification effectively regulates the surface chemical environment of copper powder and improves wettability. Following physical modification, the water contact angle of copper powder decreased from 52.9° to 50.3°, while chemical modification reduced it from 61.9° to 40.9°. FTIR spectra of modified samples exhibited characteristic absorption peaks corresponding to the modifiers, confirming alterations in surface chemical states. Copper powders prepared by different methods exhibited varying responses to modifiers, necessitating targeted regulation.

- Surface-modified copper powder exhibits enhanced coating density and interfacial stability following silver plating. Physically processed copper powder, with its higher sphericity and smoother surface, facilitates the formation of a continuous and uniform silver layer. Chemically processed copper powder, following modification, exhibits superior wettability and interfacial activity. Its charge transfer resistance after silver plating increased from 801 Ω to 1399 Ω, indicating significantly enhanced corrosion resistance and interfacial stability.

- As the silver plating content increased from 8 wt% to 15 wt%, the coating integrity and density of the silver-coated copper powder significantly improved, effectively suppressing the corrosion reaction. The self-corrosion current density of physically modified copper powder after silver plating decreased from 1.285 × 10−5 A·cm−2 to 4.671 × 10−6 A·cm−2, while chemically modified samples decreased from 1.120 × 10−5 A·cm−2 to 5.075 × 10−6 A·cm−2. However, excessively high silver content readily leads to silver precipitation and the formation of free particles, thereby inducing risks of corrosion and electromigration. This necessitates optimized control between performance and cost.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, Y.; Cui, B.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Lin, B. Uniformly Coated Cu@Ag Core-Shell Particles with Low Silver Content: Hydroxy Acid as a Complexing Agent with “Double-Sided Adhesive” Function. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 46, 104137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, G.R.; Jourdan, J.; Bastide, S.; Favre, W. Evaluation of Commercial Pure Conductive Copper Pastes by Screen Printing for A-Si:H/c-Si Heterojunction Solar Cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 292, 113690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheibarian, Z.; Soleimani, E.; Mardani, H.R. Photocatalytic Activity of Cu@Ag BNCs Synthesized by the Green Method: Photodegradation Methyl Orange and Indigo Carmine. Inorg. Nano-Met. Chem. 2023, 53, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruces, E.; Arancibia-Miranda, N.; Manquián-Cerda, K.; Perreault, F.; Bolan, N.; Azócar, M.I.; Cubillos, V.; Montory, J.; Rubio, M.A.; Sarkar, B. Copper/Silver Bimetallic Nanoparticles Supported on Aluminosilicate Geomaterials as Antibacterial Agents. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 1472–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.I.; Lee, J.-H. Die Sinter Bonding in Air Using Cu@Ag Particulate Preform and Rapid Formation of Near-Full Density Bondline. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 1724–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Hu, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, F.; Liu, P.; Yu, Y.; Feng, Q.; Xiao, X. Highly Stretchable, Tough, and Conductive Ag@Cu Nanocomposite Hydrogels for Flexible Wearable Sensors and Bionic Electronic Skins. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2021, 306, 2100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Subramanian, V. Screen-Printable Cu–Ag Core–Shell Nanoparticle Paste for Reduced Silver Usage in Solar Cells: Particle Design, Paste Formulation, and Process Optimization. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2022, 4, 4929–4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-S.; An, C.Y.; Kannan, P.K.; Seo, N.; Zhuo, K.; Yoo, T.K.; Chung, C.-H. Fabrication of Dendritic Silver-Coated Copper Powders by Galvanic Displacement Reaction and Their Thermal Stability against Oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 389, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, O.; Varol, T.; Alver, Ü.; Çanakçı, A. The Effect of Flake-like Morphology on the Coating Properties of Silver Coated Copper Particles Fabricated by Electroless Plating. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 782, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, H.T.; Ahn, J.G.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, J.R.; Chung, H.S.; Kim, C.O. Developing Process for Coating Copper Particles with Silver by Electroless Plating Method. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 201, 3788–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.G.; Zhang, H.Y. Fabrication and Performance of Silver Coated Copper Powder. Electron. Mater. Lett. 2012, 8, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Kim, H.; Song, K.H.; Choe, J. Synthesis of Silver-Coated Copper Particles with Thermal Oxidation Stability for a Solar Cell Conductive Paste. Chem. Lett. 2015, 44, 1223–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh Chaudhuri, R.; Paria, S. Core/Shell Nanoparticles: Classes, Properties, Synthesis Mechanisms, Characterization, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 2373–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Lin, G.; Wang, S.; Hu, T.; Li, S.; Xia, H.; Zhang, L. Preparation methods and research progress of copper powder. Chin. J. Nonferrous Met. 2025, 35, 3325–3349. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Hou, H.; Dang, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. Preparation of Micron Copper Powder and Its Application in the Field of Flexible Electronics. Chem. Ind. Eng. Prog. 2025, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Chen, C.; Zhang, C.; Xiao, N.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z. Effects of Ball Milling on Powder Particle Boundaries and Properties of ODS Copper. High Temp. Mater. Process. 2021, 40, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yao, Q.; Liu, G.; Tu, G.; Zhou, Z.; Ding, M.; Xu, H. Performance of Spherical Powder Manufactured by Arc Plasma Micro-Blasting. Mater. Rep. 2020, 34, 1386–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Feng, G.; Li, W.; Yin, J.; Zhou, S. Preparation and Phase Analysis of Cu Nano power by Electrical Explosion. High Power Laser Part Beams 2013, 25, 2408–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yu, S. Process Optimization on Preparation of Nanometer Copper Powder by Reduction of Hydrazine Hydrate. Hunan Nonferrous Met. 2019, 35, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, A.K.S.; Magnago, L.B.; Pegoretti, V.C.B.; De Freitas, M.B.J.G.; Lelis, M.F.F.; Fabris, J.D.; Porto, A.O. Copper Local Structure in Spinel Ferrites Determined by X-Ray Absorption and Mössbauer Spectroscopy and Their Catalytic Performance. Mater. Res. Bull. 2019, 109, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, N.; Han, S.; Jiang, Q.; Wei, Y.; Wang, H. Preparation of Dendritic Copper Powder by Electrolysis of Scrap Copper in A New Electrolytic Clle. Hydrometall. China 2023, 42, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Wang, C.; Qing, Q. Effect of PEG10000 Concentrations on the Localized Electrochemical Deposition of Copper Microcolumns at Various Deposition Voltages. China Surf. Eng. 2025, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Hou, B.; Shu, S.; Li, A.; Geng, Q.; Li, H.; Shi, Y.; Yang, M.; Du, S.; Wang, J.-Q.; et al. High Oxidation Resistance of CVD Graphene-Reinforced Copper Matrix Composites. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramović, L.; Maksimović, V.M.; Baščarević, Z.; Ignjatović, N.; Bugarin, M.; Marković, R.; Nikolić, N.D. Influence of the Shape of Copper Powder Particles on the Crystal Structure and Some Decisive Characteristics of the Metal Powders. Metals 2019, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Cao, M.; Lin, J.; Liu, T.; Zhu, X. Preparation and Anti-Oxidisation Resistance of Silver-Coated Copper Powders by Cobalt-Modified Copper Powders. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 40, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, X.; Yang, N.; Li, X.; Yang, B. Mechanism of Free Silver Formation While Preparing Silver-Coated Copper Powder by Chemical Plating and Its Control. Coatings 2025, 15, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Kuang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zeng, X. Surface Morphology Control of Ag-Coated Cu Particles and Its Effect on Oxidation Resistance. Coatings 2025, 15, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhu, X.; Cao, M.; Long, J. Preparation and Properties of Silver-Coated Copper Powder with Sn Transition Layer. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 076563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, K.; Jiang, B.; Liang, X. Co-addition of Al and Cu on microstructure and corrosion behavior of FeCoNiAlCu high-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Eng. 2025, 53, 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Štrbák, M.; Kajánek, D.; Knap, V.; Florková, Z.; Pastorková, J.; Hadzima, B.; Goraus, M. Effect of Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation on the Short-Term Corrosion Behaviour of AZ91 Magnesium Alloy in Aggressive Chloride Environment. Coatings 2022, 12, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Huang, H.; Huang, G. Galvanic Corrosion Behavior between ADC12 Aluminum Alloy and Copper in 3.5 Wt% NaCl Solution. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 927, 116984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbilen, S.; Ünal, A.; Sheppard, T. Influence of Superheat on Particle Shape and Size of Gas Atomised Copper Powders. Powder Metall. 1991, 34, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Deng, D.; Huang, Q.; Xu, X.; Xie, Y. Development and Thermal Performance of a Vapor Chamber with Multi-Artery Reentrant Microchannels for High-Power LED. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 166, 114686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S. Preparation of Fine Copper Powder Using Ascorbic Acid as Reducing Agent and Its Application in MLCC. Mater. Lett. 2007, 61, 1125–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, D.K.; Wendt, R.C. Estimation of the Surface Free Energy of Polymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1969, 13, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero de Hijes, P.; Shi, K.; Noya, E.G.; Santiso, E.E.; Gubbins, K.E.; Sanz, E.; Vega, C. The Young–Laplace Equation for a Solid–Liquid Interface. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 191102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibowski, E. Some Problems of Characterization of a Solid Surface via the Surface Free Energy Changes. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2017, 35, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, H.; Li, M. The Synergistic Effect of Micron Spherical and Flaky Silver-Coated Copper for Conductive Adhesives to Achieve High Electrical Conductivity with Low Percolation Threshold. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2022, 114, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravis, D.; Poncin-Epaillard, F.; Coulon, J.-F. Correlation between the Surface Chemistry, the Surface Free Energy and the Adhesion of Metallic Coatings onto Plasma-Treated Poly(Ether Ether Ketone). Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 501, 144242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, E.C.; Geldart, D. The Use of Bulk Density Measurements as Flowability Indicators. Powder Technol. 1999, 102, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, Z.; Pourabdoli, M. Physical and Chemical Properties of Ag–Cu Composite Electrical Contacts Prepared by Cold-Press and Sintering of Silver-Coated Copper Powder. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 290, 126608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershov, B.; Abkhalimov, E.V. Colloidal Copper and Peculiarities of Its Reaction with Silver Ions in Aqueous Solution. Colloid J. 2009, 71, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokuniaeva, A.O.; Vorokh, A.S. Estimation of Particle Size Using the Debye Equation and the Scherrer Formula for Polyphasic TiO2 Powder. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1410, 012057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Jeong, S.; Park, Y.; Shin, Y.; Jeong, H. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis of Damaged Layer During Polishing of Silicon Carbide. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2022, 24, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Fan, S.; Lv, D.; Tang, X.; Peng, K.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Lv, J.; Zhou, M. Process Optimization of Silver-Coated Copper Powders Based on the RSM-ANNHHO Approach: Achieving High-Quality Ag Coatings and Excellent Conductivity. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 74, 107692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, K.L.; Hess, D.W. A Novel Method of Etching Copper Oxide Using Acetic Acid. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2001, 148, G640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazem, M.E.; Itagaki, M. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 2025, 34, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukács, Z.; Kristóf, T. A Generalized Model of the Equivalent Circuits in the Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 363, 137199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liu, M. Corrosion Behavior of High-Strength C71500 Copper-Nickel Alloy in Simulated Seawater with High Concentration of Sulfide. Materials 2022, 15, 8513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrubovčáková, M.; Kupková, M.; Fedorková, A.; Oriňáková, R.; Zeleňák, A. Effect of Silver Content on Microstructure and Corrosion Behavior of Material Prepared from Silver Coated Iron Powder. Mater. Sci. Forum 2014, 782, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

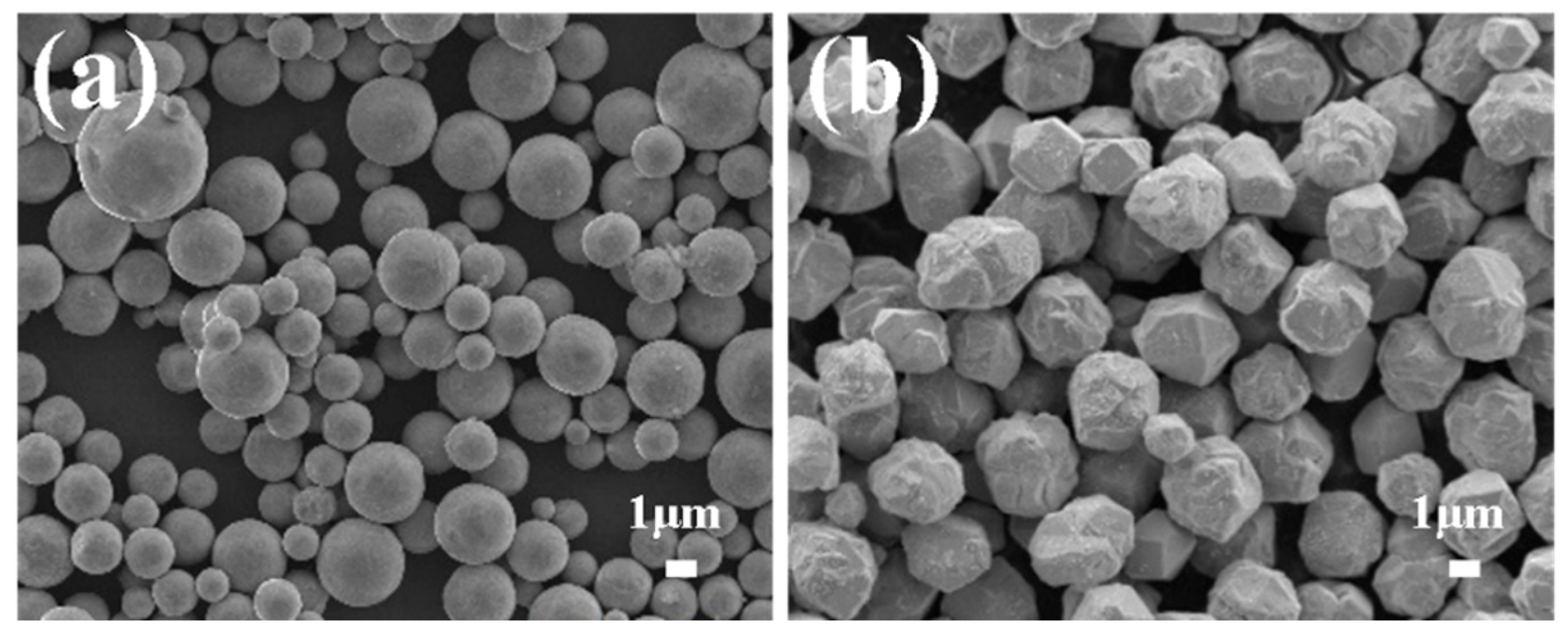

| Powder Parameters | PCu | CCu |

|---|---|---|

| Copper powder shape | Spherical | Polyhedron/Spheroidal |

| Average particle size (μm) | 3.5 | 4.75 |

| Specific surface area (m2/g) | 0.3 | 0.37 |

| Tapped density (g/cm3) | ≥4.0 | ≥4.5 |

| Wavelength (cm−1) | Assignment | Unmodified Sample | Modified Sample | Relative Intensity Ratio * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3600–3000 | O–H | medium | strong | 1.36 |

| ~1650 | C=O | weak | medium | 1.20 |

| ~1400 | –COO− | weak | medium | 1.14 |

| ~1200 | C–O | stable | stable | 1.00 |

| Sample | Theoretical Silver Content (wt%) * | Actual Silver Content (wt%) | Bulk Density (g·cm−3) | Pressed Resistor (mΩ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2-Ag1 | 8 | 7.91 | 3.16 | 4.3 |

| P2-Ag2 | 10 | 9.95 | 3.38 | 4.1 |

| P2-Ag3 | 12 | 11.92 | 3.36 | 3.7 |

| P2-Ag4 | 15 | 14.97 | 3.44 | 3.6 |

| C1-Ag1 | 8 | 7.92 | 2.72 | 4.2 |

| C1-Ag2 | 10 | 9.93 | 2.94 | 3.4 |

| C1-Ag3 | 12 | 11.9 | 2.98 | 3.2 |

| C1-Ag4 | 15 | 14.95 | 3.08 | 2.9 |

| Sample | P2-Ag1 | P2-Ag2 | P2-Ag3 | P2-Ag4 | C1-Ag1 | C1-Ag2 | C1-Ag3 | C1-Ag4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2θ (XRD) | 38.1 | 38.1 | 38.1 | 38.1 | 38.1 | 38.1 | 38.1 | 38.1 |

| FWHM (°) | 0.33707 | 0.32609 | 0.29544 | 0.29471 | 0.3309 | 0.30209 | 0.29379 | 0.29407 |

| Grain size (nm) | 24.051 | 24.857 | 27.440 | 27.505 | 24.497 | 26.835 | 27.615 | 27.565 |

| Silver Content (%) | Sample | Ecorr/mV | Icorr/ (A·cm−2) | βa/(mV/dec) | βc/(mV/dec) | Rct/Ω | Rs/Ω |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | P2-Ag1 | 36.23 | 1.285 × 10−5 | 3.142 | −2.686 | 230 | 8.519 |

| C1-Ag1 | −78.81 | 1.120 × 10−5 | 5.597 | −3.101 | 801 | 30.619 | |

| 10 | P2-Ag2 | 144.60 | 9.315 × 10−6 | 4.353 | −0.541 | 515 | 8.649 |

| C1-Ag2 | −124.56 | 7.403 × 10−6 | 8.402 | −3.616 | 320 | 31.150 | |

| 12 | P2-Ag3 | 70.20 | 3.663 × 10−6 | 5.415 | −5.694 | 374 | 10.834 |

| C1-Ag3 | −111.34 | 7.898 × 10−6 | 8.643 | −4.445 | 260 | 20.919 | |

| 15 | P2-Ag4 | 23.36 | 4.671 × 10−6 | 5.019 | −2.731 | 281 | 8.826 |

| C1-Ag4 | −84.40 | 5.075 × 10−6 | 9.107 | −8.048 | 1399 | 33.785 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, N.; Zhu, X.; Hu, J.; Li, X. Effect of Copper Powder Modification and Silver Content on Coating Adhesion and Corrosion Resistance of Silver-Coated Copper Powder. Coatings 2026, 16, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020183

Yang N, Zhu X, Hu J, Li X. Effect of Copper Powder Modification and Silver Content on Coating Adhesion and Corrosion Resistance of Silver-Coated Copper Powder. Coatings. 2026; 16(2):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020183

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Nan, Xiaoyun Zhu, Jin Hu, and Xiang Li. 2026. "Effect of Copper Powder Modification and Silver Content on Coating Adhesion and Corrosion Resistance of Silver-Coated Copper Powder" Coatings 16, no. 2: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020183

APA StyleYang, N., Zhu, X., Hu, J., & Li, X. (2026). Effect of Copper Powder Modification and Silver Content on Coating Adhesion and Corrosion Resistance of Silver-Coated Copper Powder. Coatings, 16(2), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020183