A Study on the Mechanical Properties of Ni-Al Alloy Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

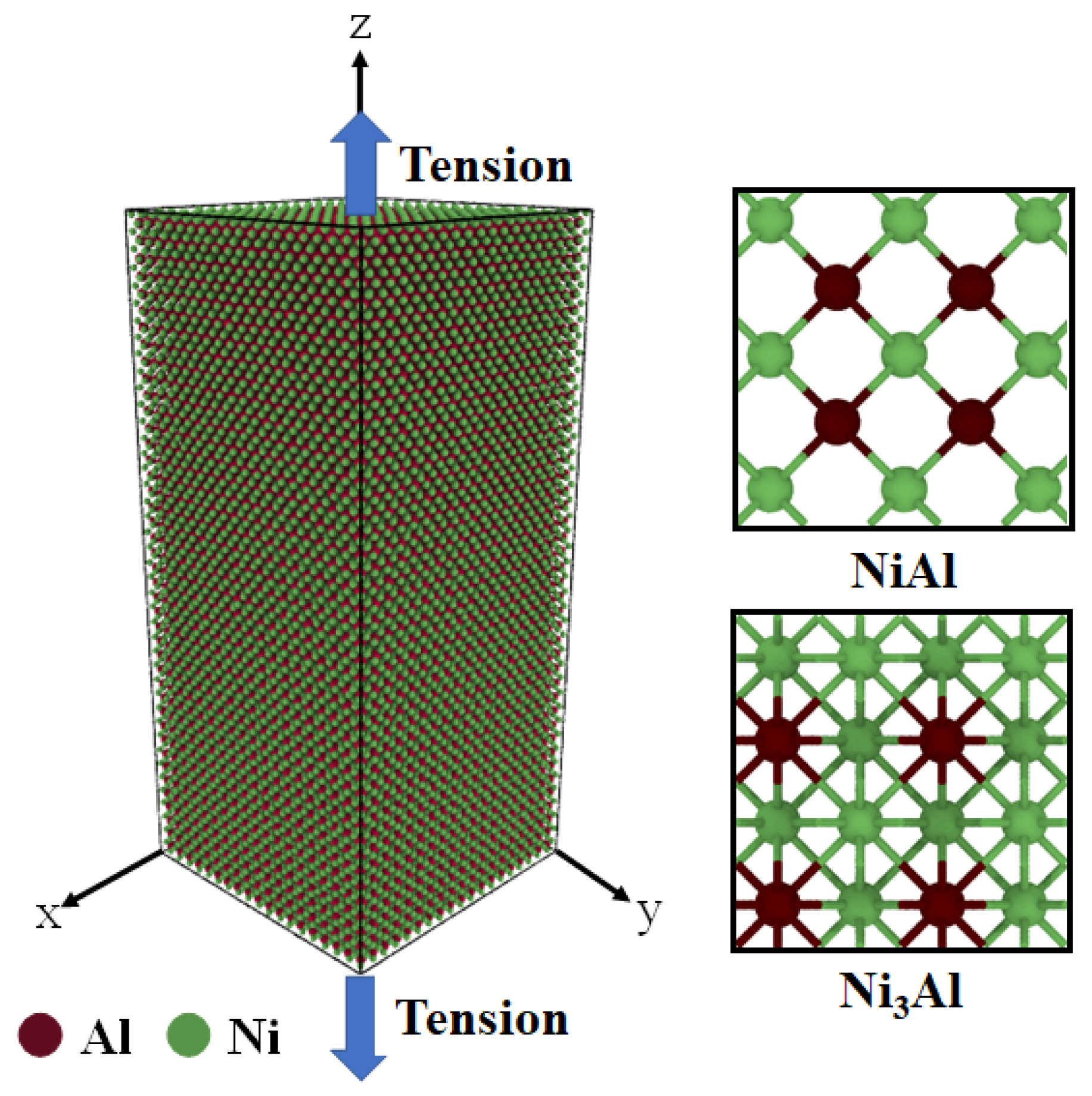

2. Modeling and Simulation Details

3. Results and Discussion

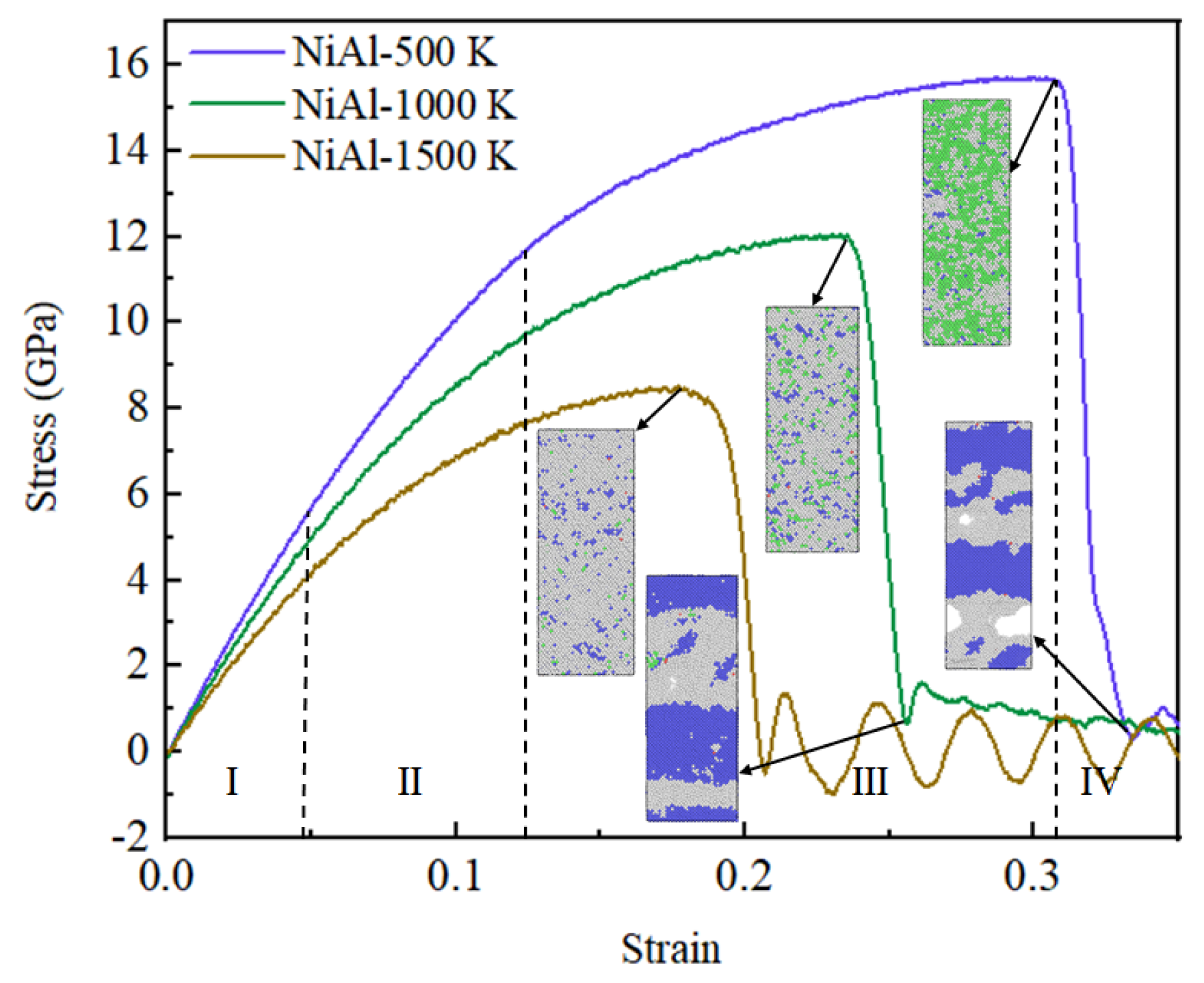

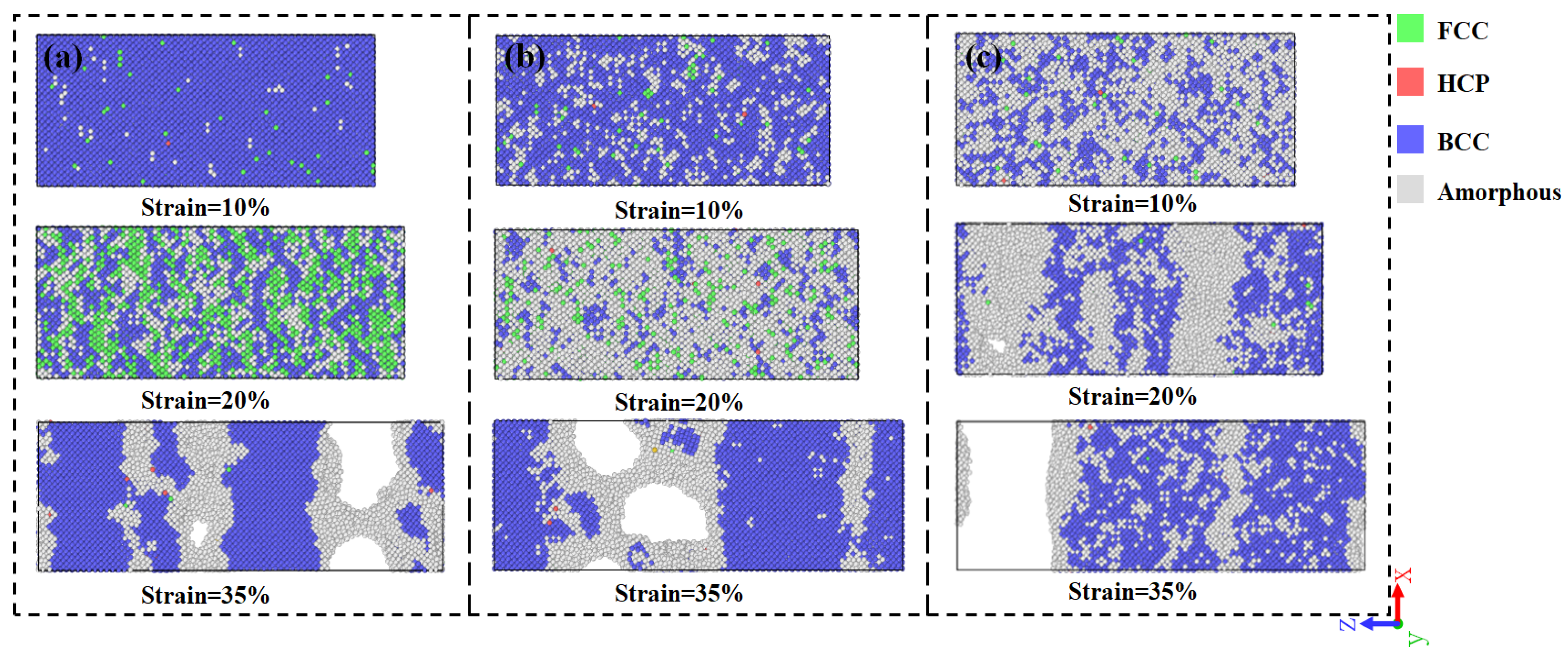

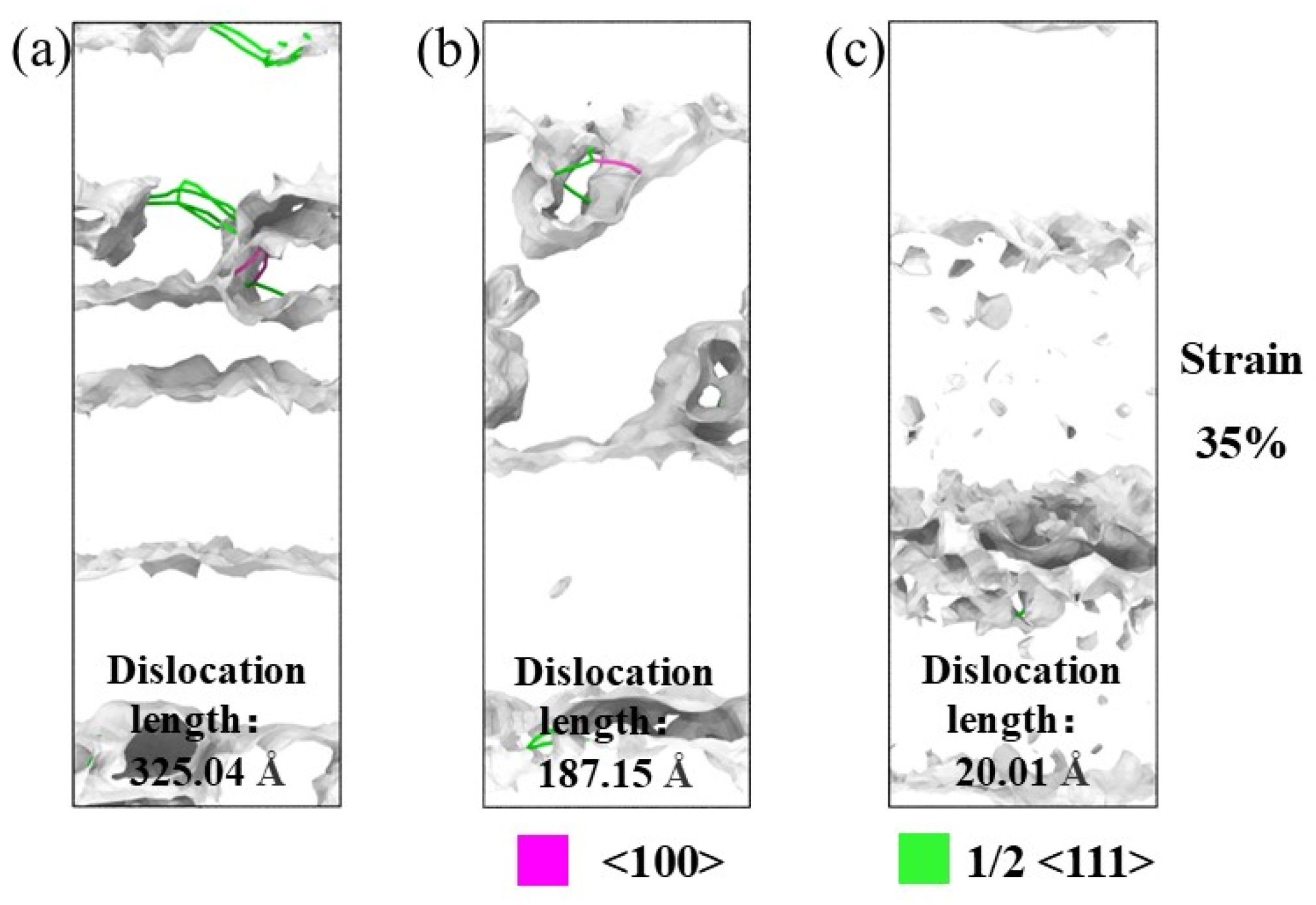

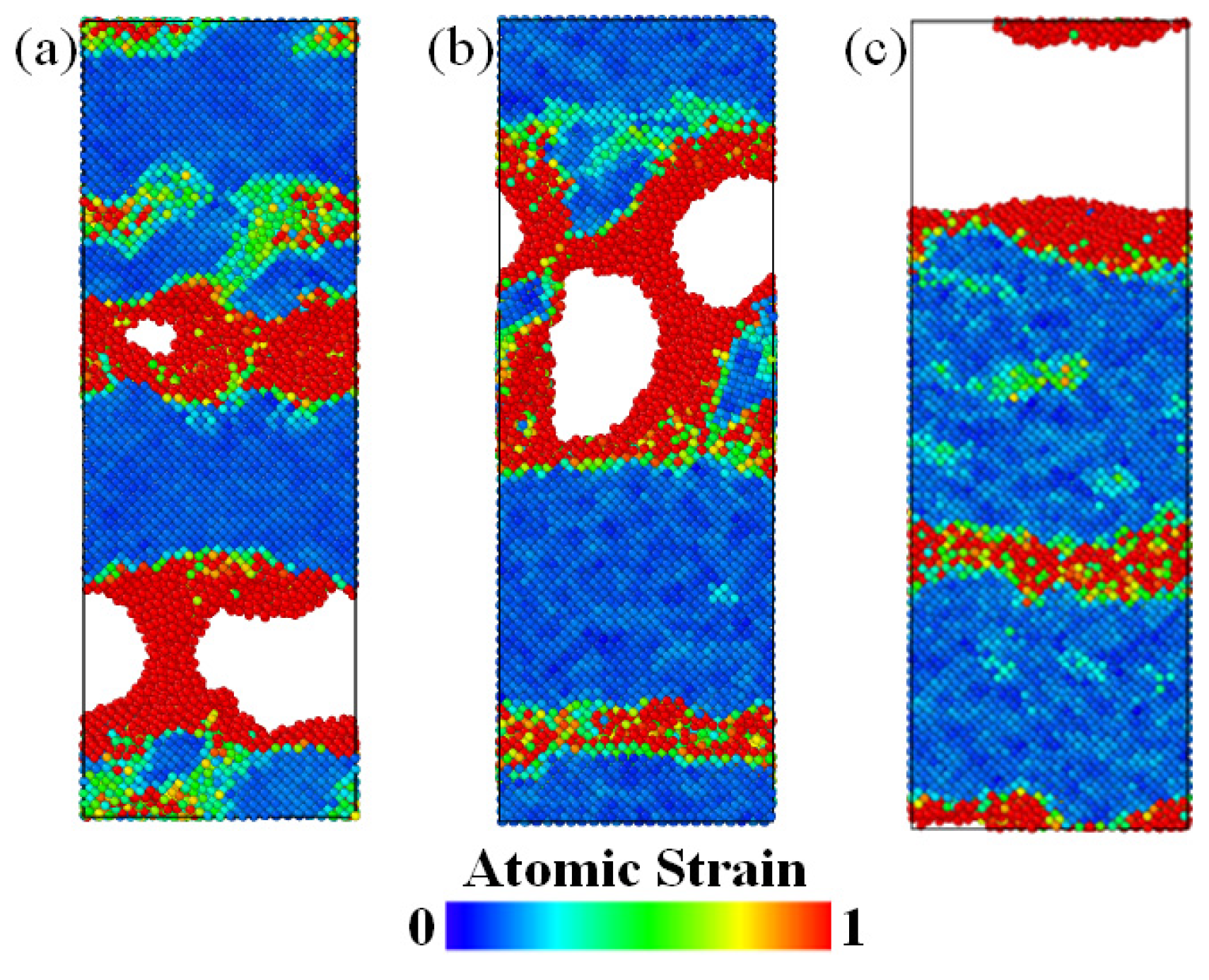

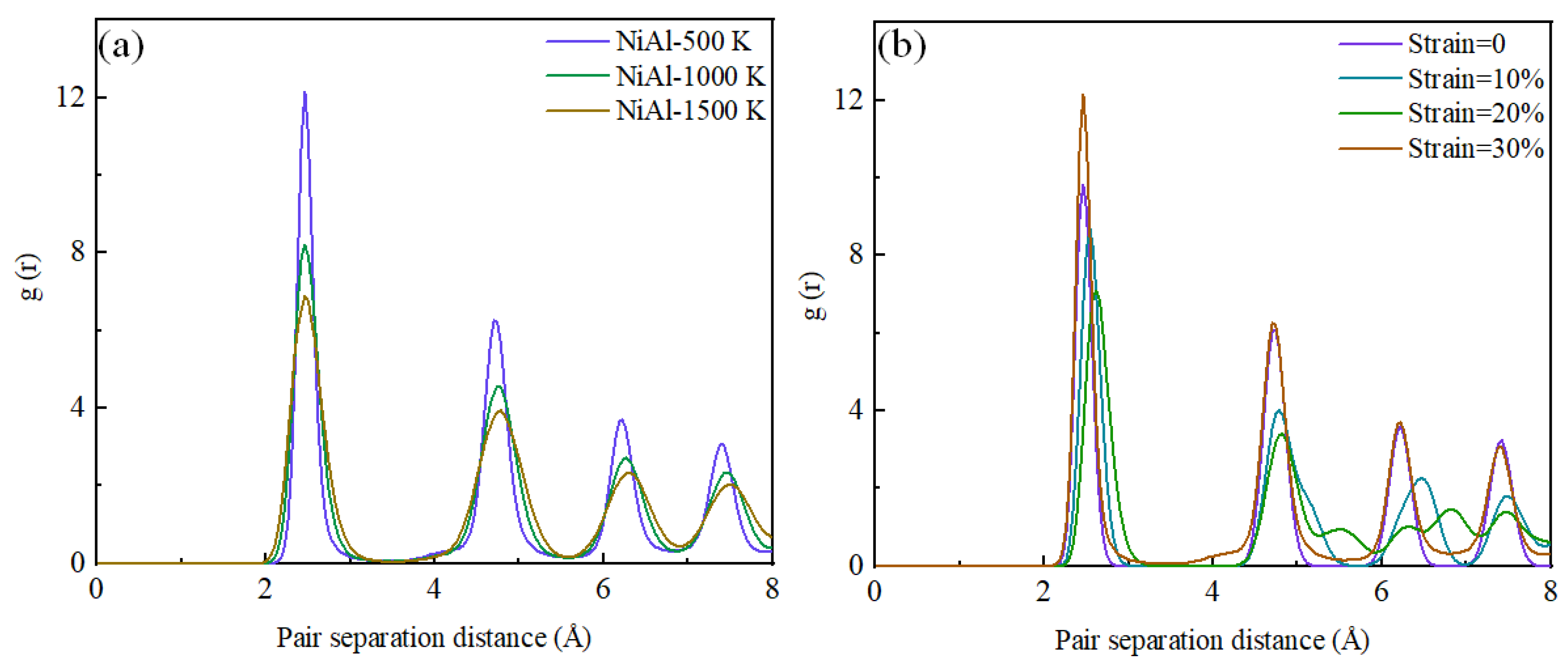

3.1. Tensile Analysis of NiAl

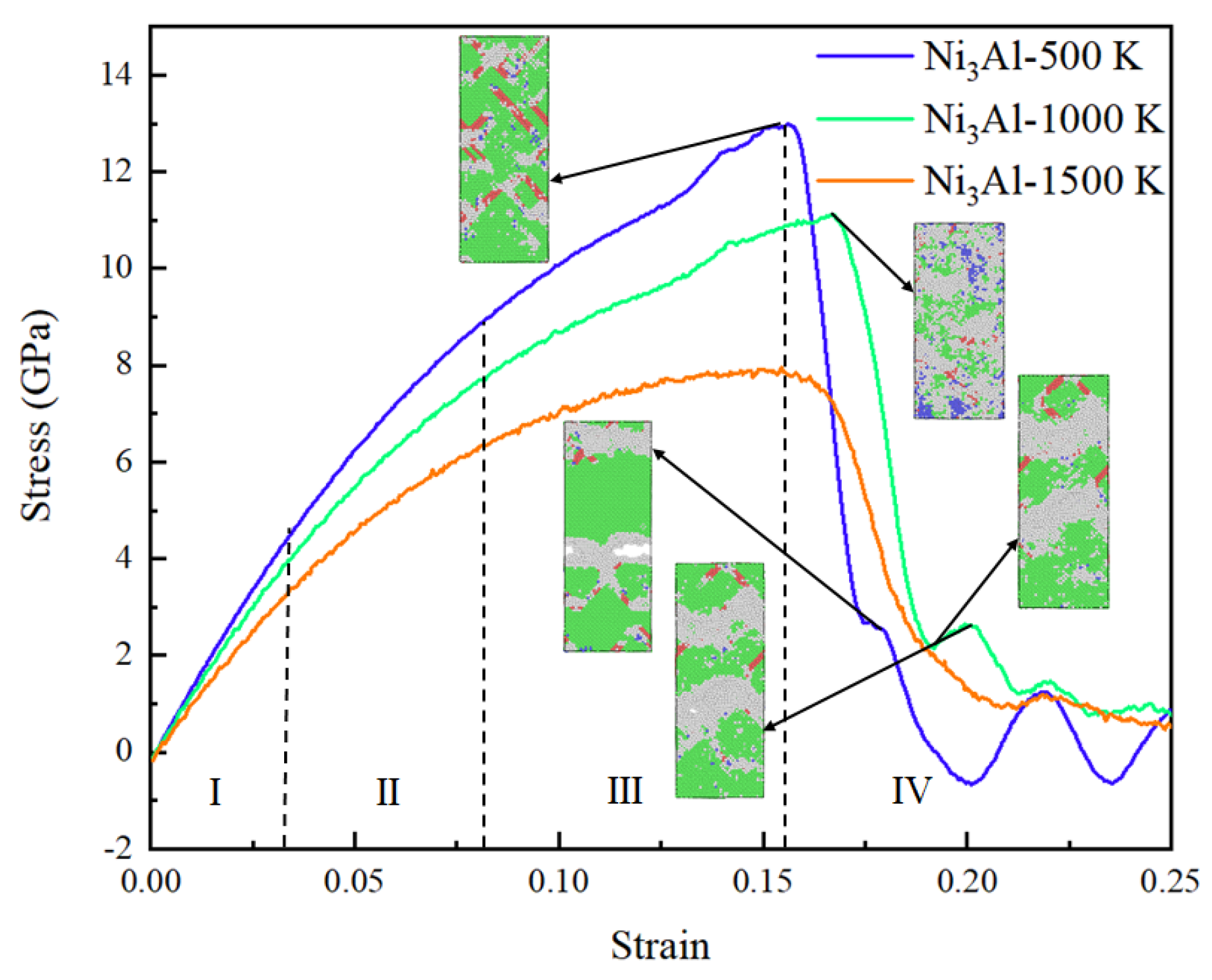

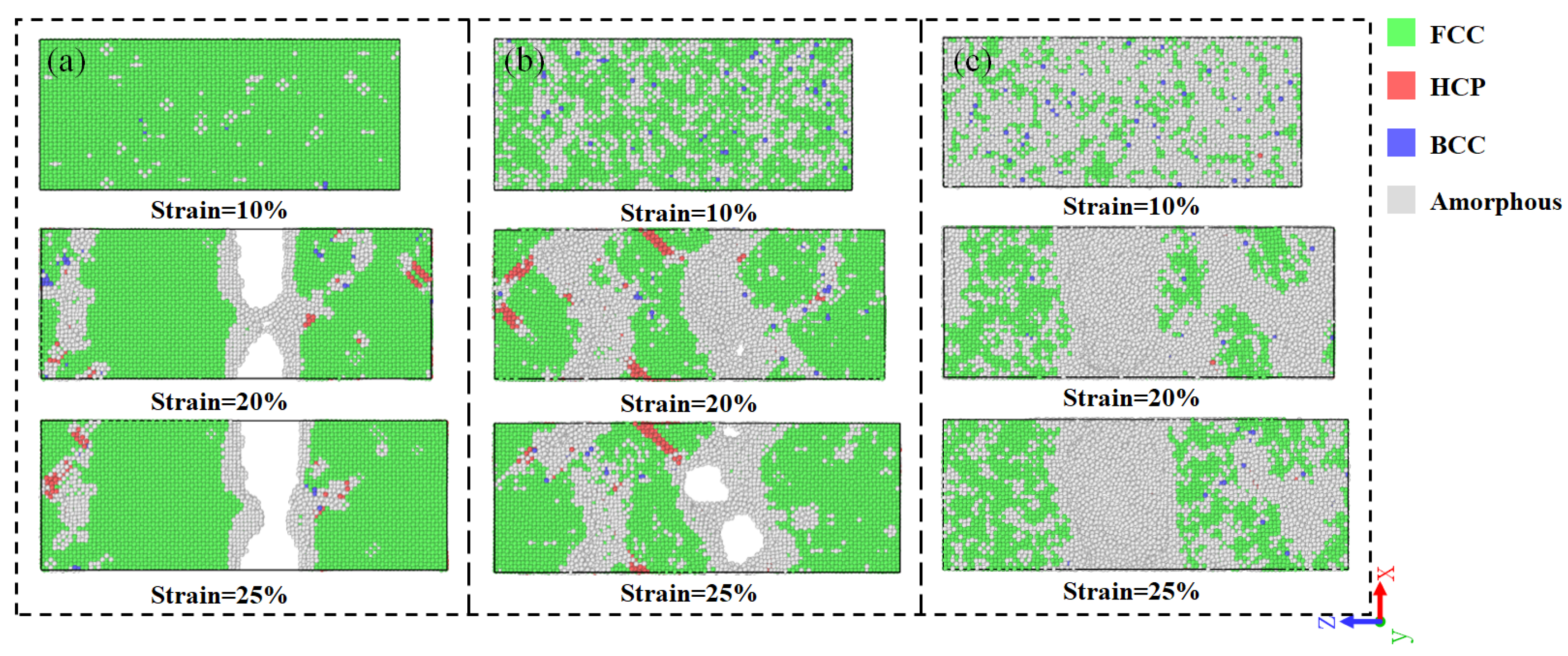

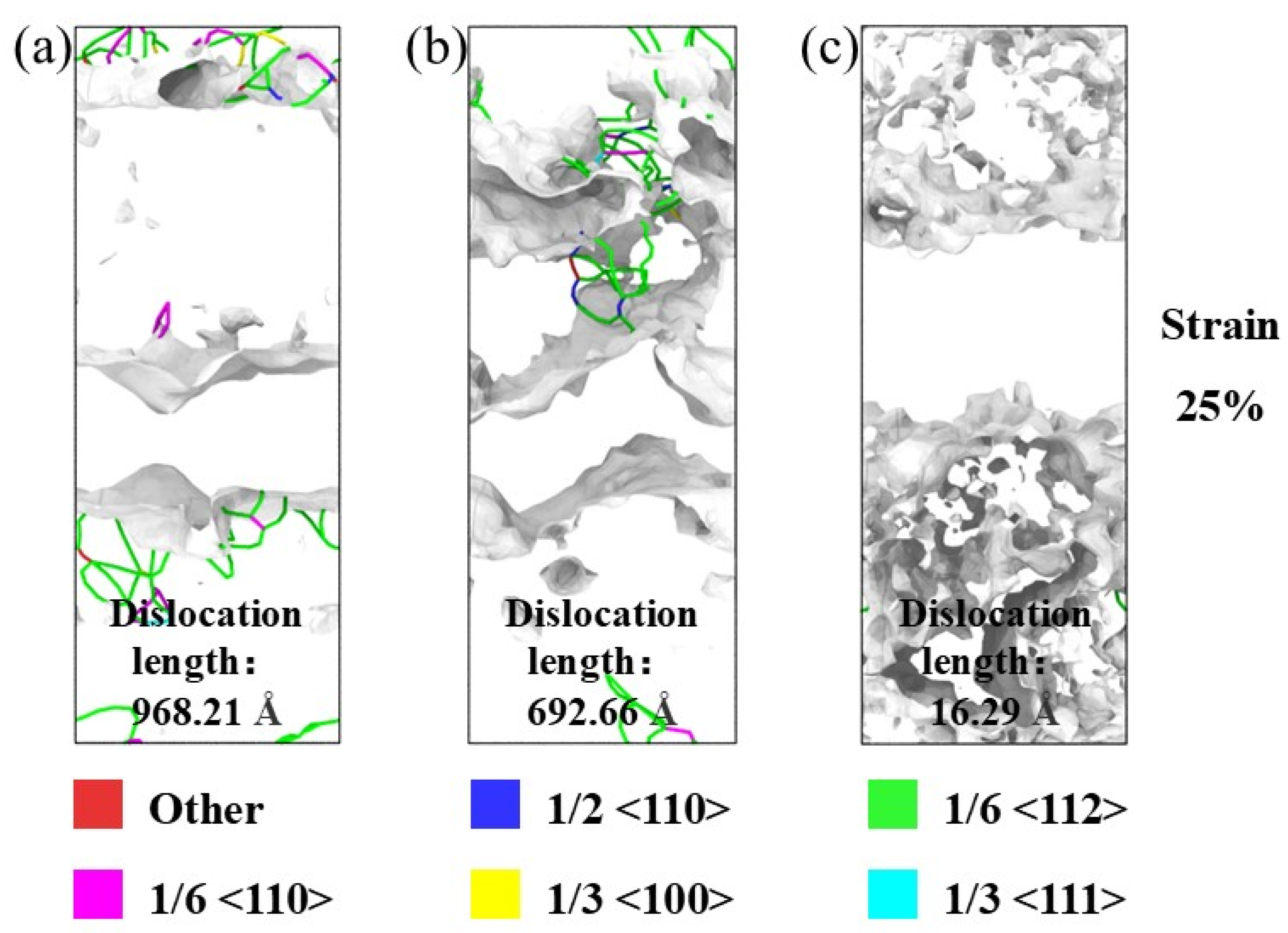

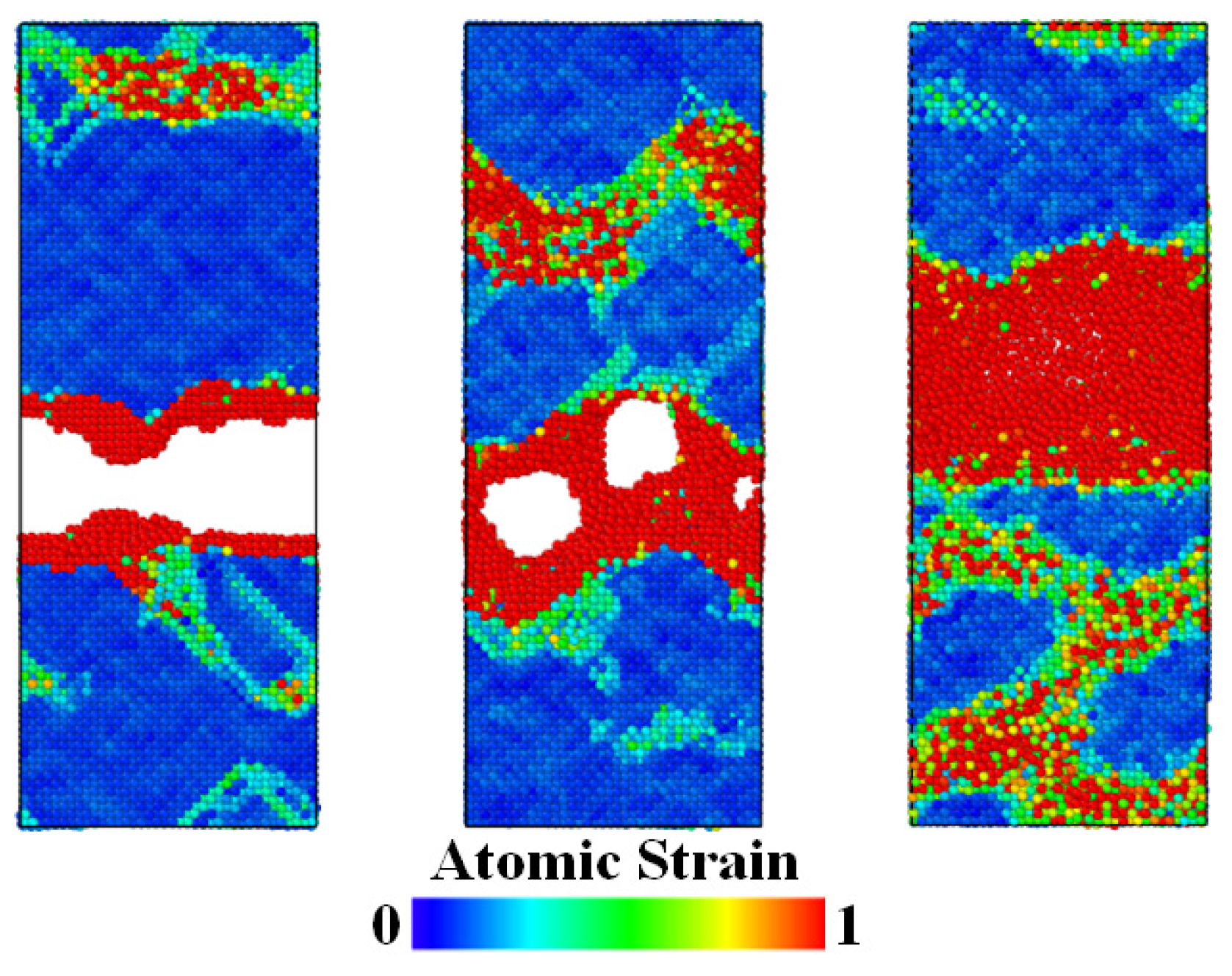

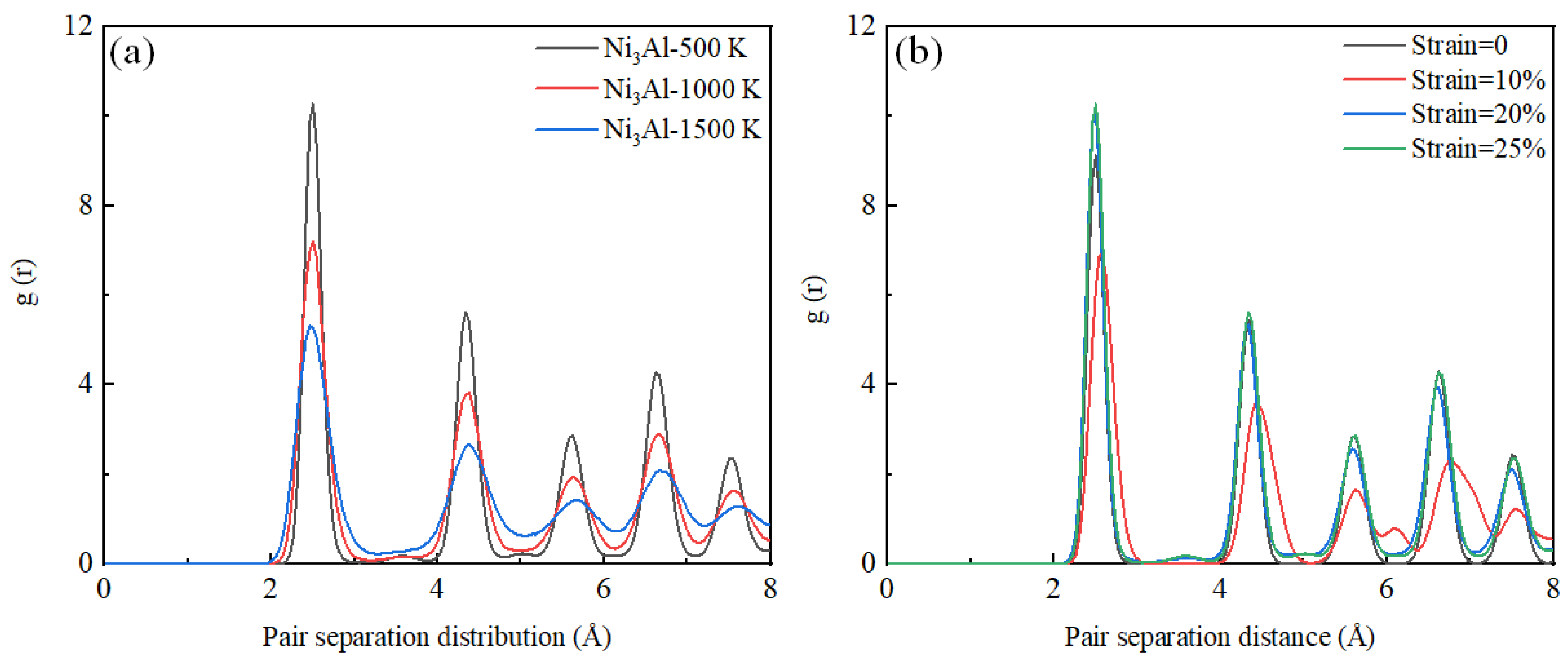

3.2. Tensile Analysis of Ni3Al

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zeng, Q.; Chen, X. Combustor technology of high temperature rise for aero engine. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2023, 140, 100927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Sethi, V.; Nalianda, D.; Li, Y.G.; Wang, L. Review of modern low emissions combustion technologies for aero gas turbine engines. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2017, 94, 12–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avan Heerden, S.J.; Judt, D.M.; Jafari, S.; Lawson, C.P.; Nikolaidis, T.; Bosak, D. Aircraft thermal management: Practices, technology, system architectures, future challenges, and opportunities. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2022, 128, 100767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrut, M.; Caron, P.; Thomas, M.; Couret, A. High temperature materials for aerospace applications: Ni-based superalloys and γ-TiAl alloys. Comptes Rendus Phys. 2018, 19, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, P.; Manna, I. Advanced high-temperature structural materials in petrochemical, metallurgical, power, and aerospace sectors—An overview. In Future Landscape of Structural Materials in India; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 79–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darolia, R. Development of strong, oxidation and corrosion resistant nickel-based superalloys: Critical review of challenges, progress and prospects. Int. Mater. Rev. 2019, 64, 355–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Li, S. Formation mechanism and prediction of new phases in binary metallic liquid/solid interface. Rare Met. 2011, 30, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Huang, T.; Song, P.; Shah, S.H.; Ali, R.; Arif, M.; Lu, J. First-principle-based structural and thermodynamic parameters of Ni–Al intermetallic compounds under different pressures and temperatures. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2021, 35, 2150124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Feng, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, E.; Ding, J.; Dai, J.; Liu, Y. Short-term corrosion behavior of polycrystalline Ni3Al-based superalloy in sulfur-containing atmosphere. Intermetallics 2022, 142, 107446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.; Rodríguez, G.P.; Marjaliza, E. Processing of intermetallic laminates by Self-Propagating High–Temperature Synthesis initiated with concentrated solar energy. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 891, 161876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, B.; Aghdam, A.S.R.; Gholami, G. A study on nanostructured in-situ oxide dispersed NiAl coating and its high temperature oxidation behavior. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 276, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, W. Comparison of oxidation resistance of Al–Ti and Al–Ni intermetallic formed in situ by thermal spraying. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 096408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wang, L.; Liang, Y.J.; Xue, Y.; Wang, L. Improving the ductility of high-strength multiphase NiAl alloys by introducing multiscale high-entropy phases and martensitic transformation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 808, 140949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnowski, M.; Gierlotka, S.; Ciołek, S.; Kulik, T. Nanocrystalline NiAl intermetallic alloy with high hardness produced by mechanical alloying and hot-pressing consolidation. Adv. Powder Technol. 2019, 30, 1312–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, G.P.P.; Mishin, Y. Molecular dynamics simulation of the martensitic phase transformation in NiAl alloys. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2010, 22, 395403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.M. Effects of interfacial stress in phase field approach for martensitic phase transformation in NiAl shape memory alloys. Appl. Phys. A 2020, 126, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, S.; Song, Y.; Jiang, H.; Rong, L. Precipitation behavior of Cu-NiAl nanoscale particles and their effect on mechanical properties in a high strength low alloy steel. Mater. Charact. 2022, 190, 112014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plimpton, S. Fast Parallel Algorithms for Short-Range Molecular Dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 1995, 117, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.M.T.; Grindon, C.; Harris, S.; Evans, T.; Novik, K.; Coveney, P.; Laughton, C. Large-scale molecular dynamics simulation of DNA: Implementation and validation of the AMBER98 force field in LAMMPS. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2004, 362, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Wang, C. First-principles studies of effects of interstitial boron and carbon on the structural, elastic, and electronic properties of Ni solution and Ni3Al intermetallics. Chin. Phys. B 2016, 25, 107104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartbauer, M.; Daoud, H.; Scherm, F.; Schumann, H.; Barroso, G.; Scherm, F.; Glatzel, U. Fe/Al and Ni/Al coatings–composition and intermetallic formation. Surf. Eng. 2025, 41, 928–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, M.H. Stability of superdislocations and shear faults in L12 ordered alloys. Acta Metall. 1987, 35, 1559–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivam, V.; Basu, J.; Pandey, V.K.; Shadangi, Y.; Mukhopadhyay, N.K. Alloying behaviour, thermal stability and phase evolution in quinary AlCoCrFeNi high entropy alloy. Adv. Powder Technol. 2018, 29, 2221–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toton, D.; Lorenz, C.D.; Rompotis, N.; Martsinovich, N.; Kantorovich, L. Temperature control in molecular dynamic simulations of non-equilibrium processes. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2010, 22, 074205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, N.E.; Mahjoub, R.; Law, K.J.; Ferry, M. A blended NPT/NVT scheme for simulating metallic glasses. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2017, 130, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishin, Y.; Asta, M.; Li, J. Atomistic modeling of interfaces and their impact on microstructure and properties. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 1117–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Pelaez, P.; Sanchez-Burgos, I.; Valeriani, C.; Vega, C.; Sanz, E. Seeding approach to nucleation in the NVT ensemble: The case of bubble cavitation in overstretched Lennard Jones fluids. Phys. Rev. E 2020, 101, 022611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.W.; Johnson, R.A.; Wadley, H.N.G. Misfit-energy-increasing dislocations in vapor-deposited CoFe/NiFe multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 144113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, M.S.; Baskes, M.I. Embedded-atom method: Derivation and application to impurities, surfaces, and other defects in metals. Phys. Rev. B 1984, 29, 6443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO–the Open Visualization Tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2009, 18, 015012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.R.; Zhang, R.F. AACSD: An atomistic analyzer for crystal structure and defects. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2018, 222, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Chen, L.; Gong, H.R.; Fan, J.L. Strain-stress relationship and dislocation evolution of W–Cu bilayers from a constructed n-body W–Cu potential. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2019, 31, 305002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrich, H.J.; Dollmann, A.; Grützmacher, P.G.; Gachot, C.; Eder, S.J. Automated identification and tracking of deformation twin structures in molecular dynamics simulations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 236, 112878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, D.; Ren, X.; Wang, Y. A new mechanism for low and temperature-independent elastic modulus. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregorová, E.; Černý, M.; Pabst, W.; Esposito, L.; Zanelli, C.; Hamáček, J.; Kutzendörfer, J. Temperature dependence of Young׳ s modulus of silica refractories. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimvall, G.; Magyari-Köpe, B.; Ozoliņš, V.; Persson, K. Lattice instabilities in metallic elements. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2012, 84, 945–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Zhai, Y.; Han, X. Timely and atomic-resolved high-temperature mechanical investigation of ductile fracture and atomistic mechanisms of tungsten. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Yao, Z.W.; Lu, G.H.; Deng, H.Q.; Gao, F. Mechanisms for <100> interstitial dislocation loops to diffuse in BCC iron. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Guo, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Ran, G.; Wu, L.; Qiu, X.; Deng, H.; Wu, X.; Li, Y.; et al. In-situ TEM observation and MD simulation of the reaction and transformation of <100> loops in tungsten during H2+ & He+ dual-beam irradiation. Scr. Mater. 2021, 204, 114154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresca, F.; Curtin, W.A. Mechanistic origin of high strength in refractory BCC high entropy alloys up to 1900 K. Acta Mater. 2020, 182, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.I.; Woodward, C.; Akdim, B.; Senkov, O.N.; Miracle, D. Theory of solid solution strengthening of bcc chemically complex alloys. Acta Mater. 2021, 209, 116758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.; Fu, T.; Peng, X.; Chen, X. Anisotropic Phase Transformation in B2 Crystalline CuZr Alloy. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, C.; Li, Q.; Wei, X.; Zhang, B. First-Principles Study on the Alloying Segregation and Ideal Fracture at Coherent B2-NiAl and BCC-Fe Interface. Materials 2025, 18, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, F.; Li, G.; Liu, C.; Han, F.; Zhang, Y.; Muhammad, A.; Gu, H.; Guo, W.; Ren, J. Cross stacking faults in Zr(Fe,Cr)2 face-centered cubic Laves phase nanoparticle. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 513, 145716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, C.R.; Boyce, B.L.; Battaile, C.C. Slip planes in bcc transition metals. Int. Mater. Rev. 2013, 58, 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröger, R.; Vitek, V. Impact of non-Schmid stress components present in the yield criterion for bcc metals on the activity of {110} <111> slip systems. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2019, 159, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Cai, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Tan, C. Analysis of crystallographic twinning and slip in fcc crystals under plane strain compression. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 464, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Zhou, Z.; Li, S. Co-yield surfaces for {111} <110> slip and {111} <112> twinning in fcc metals. J. Mater. Sci. 2002, 37, 2843–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, X.; Zhou, K.; Han, X.; Song, S.; Zheng, F.; Yang, J.; Li, R. A Study on the Mechanical Properties of Ni-Al Alloy Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Coatings 2026, 16, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020168

Yang X, Zhou K, Han X, Song S, Zheng F, Yang J, Li R. A Study on the Mechanical Properties of Ni-Al Alloy Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Coatings. 2026; 16(2):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020168

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Xuejin, Kemin Zhou, Xu Han, Shaoyun Song, Fangyan Zheng, Junsheng Yang, and Rui Li. 2026. "A Study on the Mechanical Properties of Ni-Al Alloy Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulation" Coatings 16, no. 2: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020168

APA StyleYang, X., Zhou, K., Han, X., Song, S., Zheng, F., Yang, J., & Li, R. (2026). A Study on the Mechanical Properties of Ni-Al Alloy Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Coatings, 16(2), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020168