Biodegradable Polymer Films Based on Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose and Blends with Zein and Investigation of Their Potential as Active Packaging Material

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Film Fabrication

2.3. Film Characterization

2.3.1. SEM

2.3.2. FTIR

2.3.3. Mechanical Properties

2.3.4. Barrier Properties

2.3.5. Surface Properties and Hydrophilicity

2.3.6. Thermal Stability and Phase State Investigation

2.3.7. Antioxidant Activity

2.3.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface Morphology Examination

3.2. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectra of Native Compounds and Obtained Structures

3.3. Mechanical and Barrier Properties of the Investigated Samples

3.4. Wettability and Contact Angle Measurements

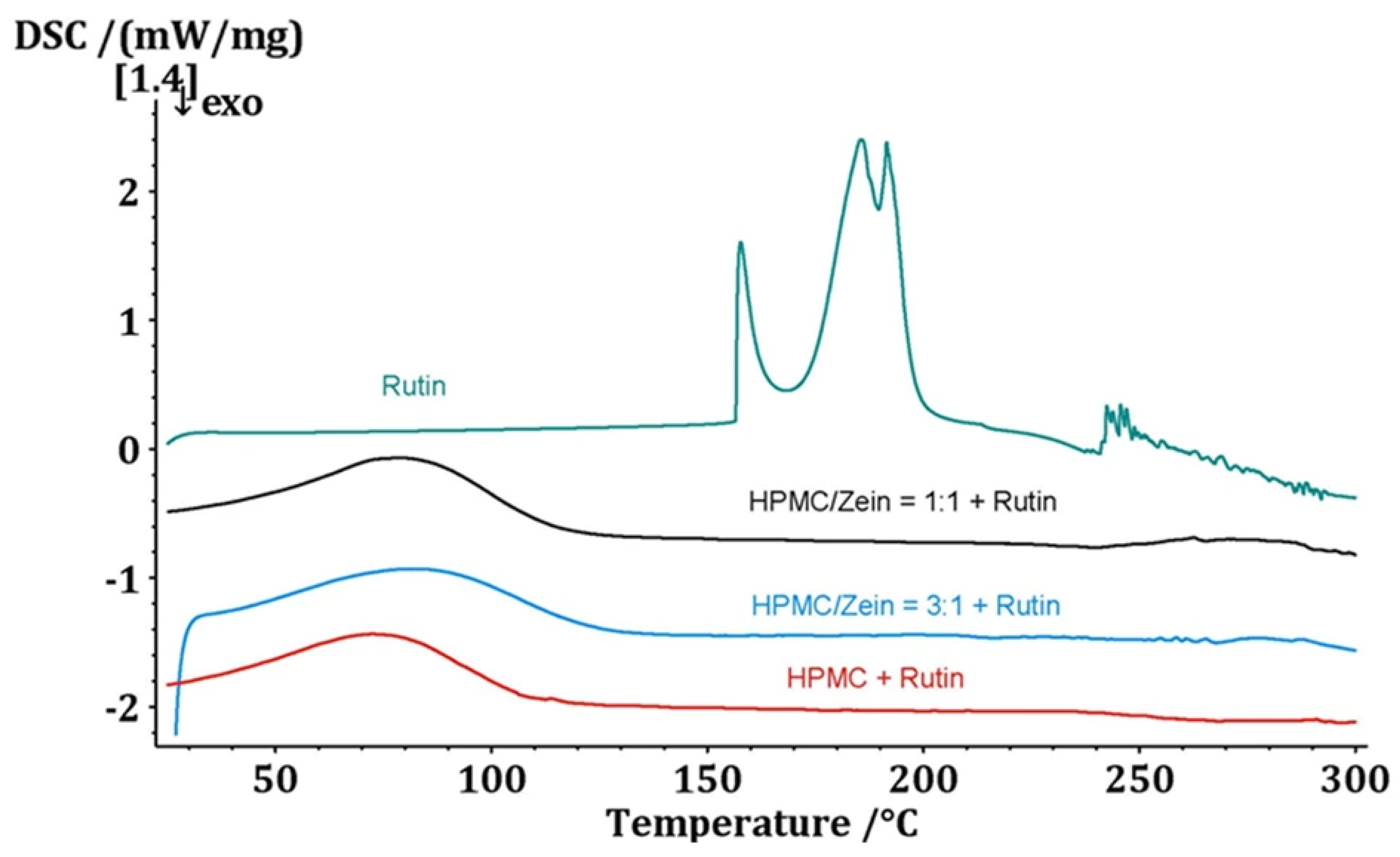

3.5. Phase State and Thermal Behavior

3.6. Antioxidant Activity Against DPPH Free Radical Solution

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, M.W.; Haque, M.A.; Mohibbullah, M.; Khan, M.S.I.; Islam, M.A.; Mondal, M.H.T.; Ahmmed, R. A review on active packaging for quality and safety of foods: Current trends, applications, prospects and challenges. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 33, 100913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasile, C.; Baican, M. Progresses in food packaging, food quality, and safety—Controlled-release antioxidant and/or antimicrobial packaging. Molecules 2021, 26, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Sun, X.; Chong, X.; Yang, M.; Zhu, Z.; Wen, Y. A review on smart active packaging systems for food preservation: Applications and future trends. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 141, 104200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasagoudr, S.S.; Hegde, V.G.; Chougale, R.B.; Masti, S.P.; Vootla, S.; Malabadi, R.B. Physico-chemical and functional properties of rutin induced chitosan/poly(vinyl alcohol) bioactive films for food packaging applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 109, 106096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Tang, B.; Zheng, T. Development of active film based on collagen and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose incorporating apple polyphenol for food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273, 132960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao-Sáinz, C.; Avena-Bustillos, R.J.; Wood, D.F.; Williams, T.G.; McHugh, T.H. Composite edible films based on hydroxypropyl methylcellulose reinforced with microcrystalline cellulose nanoparticles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 3753–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadermazi, R.; Hamdipour, S.; Sadeghi, K.; Ghadermazi, R.; Khosrowshahi Asl, A. Effect of various additives on properties of films and coatings derived from hydroxypropyl methylcellulose—A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 3363–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Chen, J.; Tan, K.B.; Chen, M.; Zhu, Y. Development of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose film with xanthan gum and its application as a food packaging biomaterial in enhancing banana shelf life. Food Chem. 2022, 374, 131794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Ma, Y.; Hou, Y.; Jia, S.; Cheng, S.; Su, W.; Tan, M.; Zhu, B.; Wang, H. Preparation of a pH-responsive smart film based on soy lipophilic protein/hydroxypropyl methylcellulose for salmon freshness monitoring. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2025, 47, 101436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillgren, T.; Stading, M. Mechanical and barrier properties of avenin, kafirin, and zein films. Food Biophys. 2008, 3, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Singh, S.; Kaur, A.; Singh Bakshi, M. Zein: Structure, production, film properties and applications. In Natural Polymers; RSC Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, I.S. Zein in food packaging. In Sustainable Food Packaging Technology; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2021; pp. 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özçalık, O. Preparation and Characterization of Corn Zein Nanocomposite Coated Polypropylene Films for Food Packaging Applications. Master’s Thesis, Izmir Institute of Technology, İzmir, Turkey, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Bonilla, J.; Joye, I.J.; Lim, L.T. Physicochemical properties of edible films formed by phase separation of zein and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose. LWT 2025, 218, 117504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.O.; Zambuzi, G.C.; Camargos, C.H.; Carvalho, A.C.; Ferreira, M.P.; Rezende, C.A.; de Freitas, O.; Francisco, K.R. Zein and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose acetate succinate microfibers for periodontal treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 261, 129701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Mulrey, L.; Byrne, M.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. Encapsulation of essential oils in nanocarriers for active food packaging. Foods 2022, 11, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Li, Q.; Jia, R.; Liu, W.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Zheng, M.; Cai, D.; Liu, J. Zein/gallic acid composite nanoparticles to improve the oxidation stability of corn oil Pickering emulsion. Food Sci. 2022, 43, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhu, Q.; Guo, J.; Gu, J.; Guo, J.; Wu, Y.; Ren, L.; Yang, S.; Jiang, J. Preparation and characterization of edible films from gelatin and HPMC/CMC. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Padua, G.W. Formation of zein microphases in ethanol−water. Langmuir 2010, 26, 12897–12901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, D.K.; Wendt, R.C. Estimation of polymer surface free energy. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1969, 13, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krewson, C.F.; Naghski, J. Some physical properties of rutin. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 1952, 41, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giteru, S.G.; Ali, M.A.; Oey, I. Solvent strength and biopolymer blending effects on zein–chitosan–PVA films. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 87, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yang, X.; Cao, C.; Lv, Z.; Han, C.; Guo, Q.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J. Improved antioxidant activities of edible films with curcumin-containing zein/polysaccharide. Food Biosci. 2024, 57, 103538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, H. Preparation and properties of zein–rutin composite nanoparticle/corn starch films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 169, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraisit, P.; Limmatvapirat, S.; Nunthanid, J.; Sriamornsak, P.; Luangtana-Anan, M. HPMC/polycarbophil mucoadhesive blend films via mixture design. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 65, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, A.; Yu, C.; Zang, Z.; Zhu, W.; Deng, X.; Guan, Y. Synthesis and Evaluation of Rutin–Hydroxypropyl β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes Embedded in Xanthan Gum-Based (HPMC-g-AMPS) Hydrogels for Oral Controlled Drug Delivery. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tivano, F.; Chiono, V. Zein as a renewable material for green nanoparticles. Front. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 2, 1156403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaltariov, M.F. FTIR investigation on crystallinity of HPMC blends. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2021, 55, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaltariov, M.F.; Filip, D.; Varganici, C.D.; Macocinschi, D. ATR-FTIR and Thermal Behavior Studies of New Hydrogel Formulations Based on HPMC/PAA Polymeric Blends. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2018, 52, 619–631. [Google Scholar]

- Akinosho, H.; Hawkins, S.; Wicker, L. HPMC substituent analysis and rheology. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 98, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, K.; Vijayalakshmi, E.; Korrapati, P.S. Interactions of zein microspheres with drugs. AAPS PharmSciTech 2014, 15, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Gao, A.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.T.; Chen, Y. Properties of cold plasma–modified zein. Food Bioprod. Process. 2017, 106, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; An, D.; Li, J.; Deng, S. Zein-based nanoparticles: Preparation, characterization, and pharmaceutical application. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1120251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immaculate, A.A.; Vimala, J.R.; Takuwa, D.T. Isolation and characterization of rutin from Cadaba aphylla and Adenia glauca. Orient. J. Chem. 2022, 38, 1404–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paczkowska, M.; Lewandowska, K.; Bednarski, W.; Mizera, M.; Podborska, A.; Krause, A.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Spectroscopic identification of quercetin-3-O-rutinoside. Spectrochim. Acta A 2015, 140, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutrizio, M.; Jurić, S.; Kucljak, D.; Švaljek, S.L.; Vlahoviček-Kahlina, K.; Jambrak, A.R.; Vinceković, M. Encapsulation of rosemary extracts in alginate/zein/HPMC microparticles. Foods 2023, 12, 1570.

- Madkour, D.A.; Ahmed, M.; Elkirdasy, A.F.; Orabi, S.H.; Mousa, A.A. Rutin: Chemical and biological properties. Matrouh J. Vet. Med. 2024, 4, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysa, M.; Szymańska-Chargot, M.; Zdunek, A. FT-IR and FT-Raman fingerprints of flavonoids. Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulou, E.; Maurizzi, E.; Bigi, F.; Quartieri, A.; Pulvirenti, A.; Tsironi, T. Comparative effect of different plasticizers on physicochemical properties of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose (HPMC)-based films appropriate for gilthead seabream packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 10, 100839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.; Cheng, C.J.; Jones, O.G. Vapor barrier and mechanical properties of HPMC/zein nanoparticle films. Food Biophys. 2018, 13, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luner, P.E.; Oh, E. Characterization of surface free energy of cellulose ether films. Colloids Surf. A 2001, 181, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xie, J.; Paximada, E. Electrosprayed zein/quercetin particles: Formation and properties. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2025, 18, 2840–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Xue, C.; Huang, Q. Assembly of zein–polyphenol conjugates. LWT 2022, 154, 112708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhillips, H.; Craig, D.Q.M.; Royall, P.G.; Hill, V.L. Glass transition of HPMC using MTDSC. Int. J. Pharm. 1999, 180, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisharat, L.; Berardi, A.; Perinelli, D.R.; Bonacucina, G.; Casettari, L.; Cespi, M.; AlKhatib, H.S.; Palmieri, G.F. Aggregation of zein in ethanol dispersions: Effect on film properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 106, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marudova, M.; Viraneva, A.; Milenkova, S.; Shivachev, B.; Titorenkova, R.; Tarassov, M. Polyphenols/PLA blends—structure, thermal and electret properties. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 57, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardi, A.; Voci, S.; Paolino, D.; Fresta, M.; Cosco, D. Influence of model compounds on zein-based gels. Molecules 2020, 25, 3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; Man, T.; Xiong, X.; Wang, Y.; Duan, X.; Xiong, X. HPMC films functionalized by zein/CTG emulsions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 238, 124053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Title 1 | HMPC | HPMC 3:1 Zein | HPMC 1:1 Zein | HPMC + Rutin | HPMC 3:1 Zein + Rutin | HPMC 1:1 Zein + Rutin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young’s modulus, MPa | 276.98 ± 28.48 c | 307.67 ± 30.73 c | 52.17 ± 10.19 a | 325.24 ± 69.78 d | 455.94 ± 57 e | 92.97 ± 15.80 b |

| Stress at break, MPa | 39.75 ± 3.68 d | 20.54 ± 5.34 b | 10.88 ± 1.87 a | 30.39 ± 5.17 c | 25.36 ± 3.75 b | 13.55 ± 1.82 a |

| Strain at break, % | 86.74 ± 8.64 d | 77.14 ± 12.20 c | 72.44 ± 9.62 c | 58.34 ± 9.30 b | 16.41 ± 2.55 a | 82.51 ± 9.61 d |

| Water vapor transmission rate, g/m2.24 h | 913.07 ± 74.01 c | 878.01 ± 6.29 bc | 873.05 ± 9.07 bc | 769.26 ± 40.85 a | 762.70 ± 22.18 a | 826.35 ± 33.67 ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Milenkova, S.; Marudova, M.; Viraneva, A. Biodegradable Polymer Films Based on Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose and Blends with Zein and Investigation of Their Potential as Active Packaging Material. Coatings 2026, 16, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010066

Milenkova S, Marudova M, Viraneva A. Biodegradable Polymer Films Based on Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose and Blends with Zein and Investigation of Their Potential as Active Packaging Material. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010066

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilenkova, Sofia, Maria Marudova, and Asya Viraneva. 2026. "Biodegradable Polymer Films Based on Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose and Blends with Zein and Investigation of Their Potential as Active Packaging Material" Coatings 16, no. 1: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010066

APA StyleMilenkova, S., Marudova, M., & Viraneva, A. (2026). Biodegradable Polymer Films Based on Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose and Blends with Zein and Investigation of Their Potential as Active Packaging Material. Coatings, 16(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010066