Ensemble Machine Learning for Predicting Machining Responses of LB-PBF AlSi10Mg Across Distinct Cutting Environments with CVD Cutter

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Setup

2.1. Fabrication and Machining

2.2. Cooling Conditions

2.3. Measurement

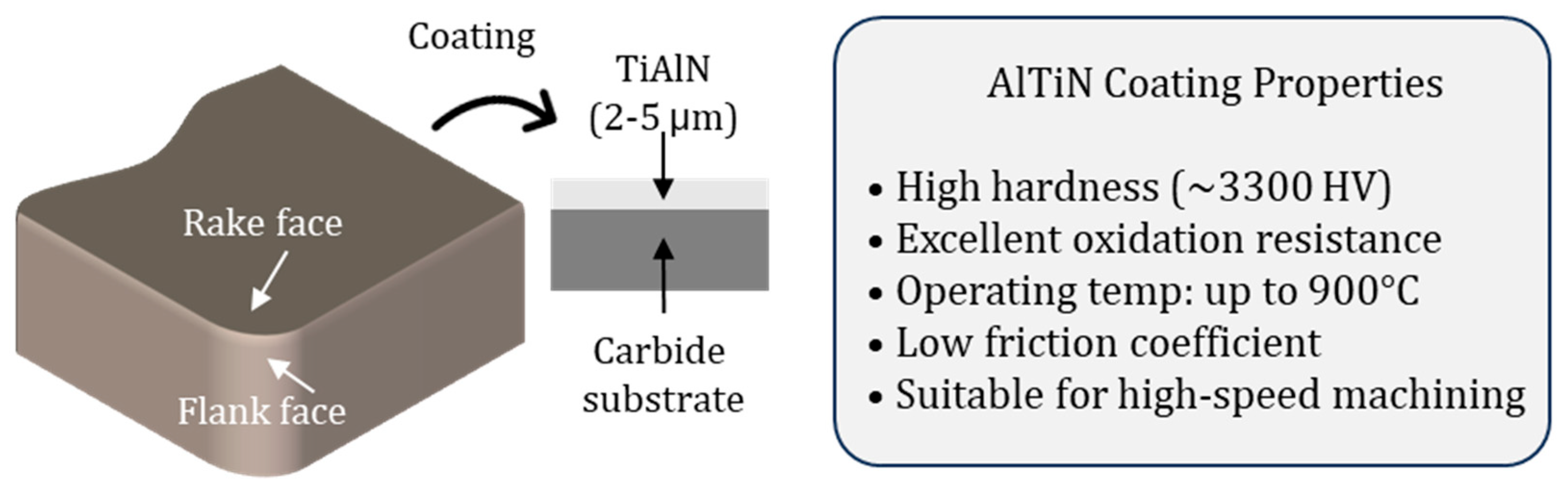

3. Tool Material

4. Results and Discussions

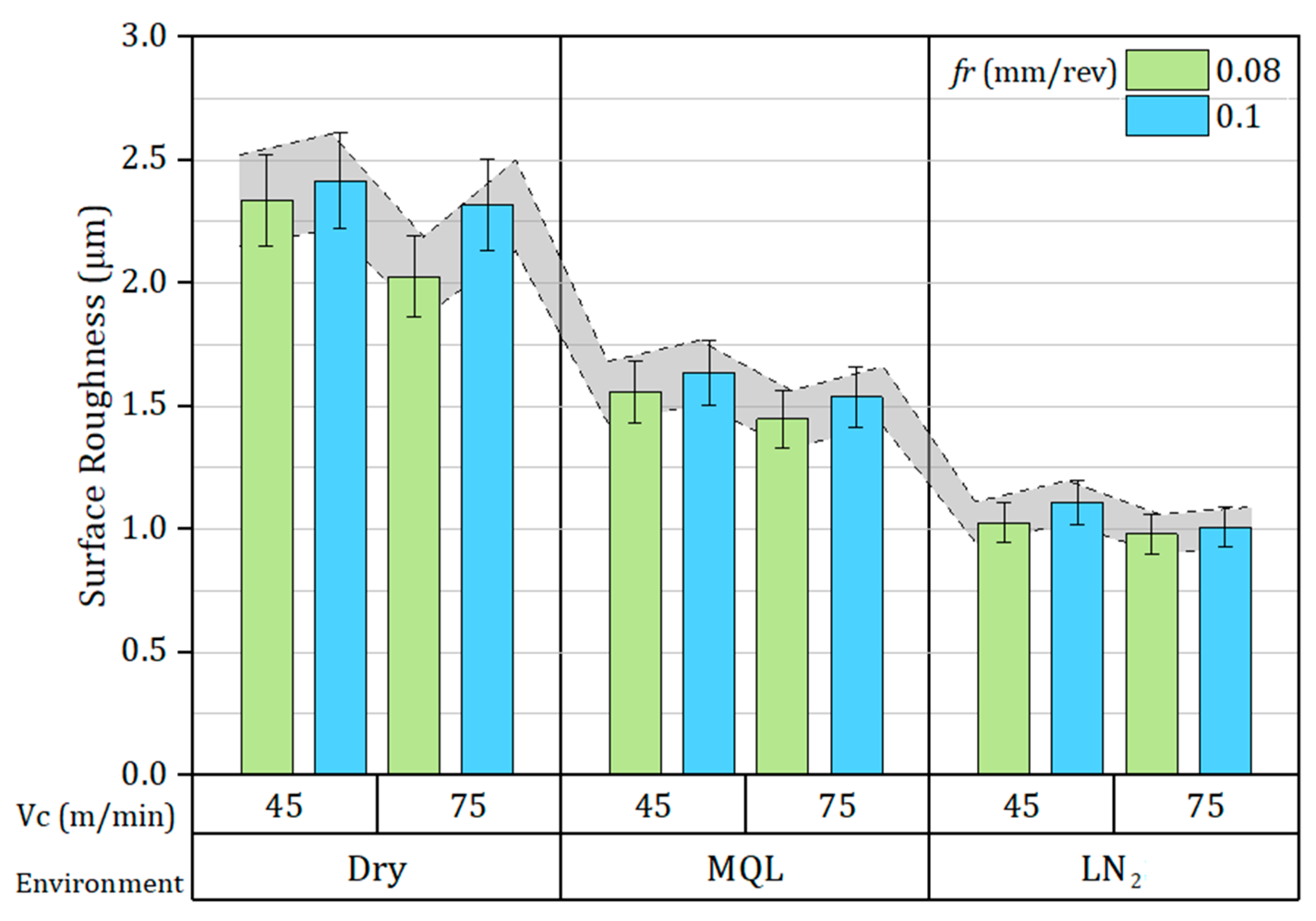

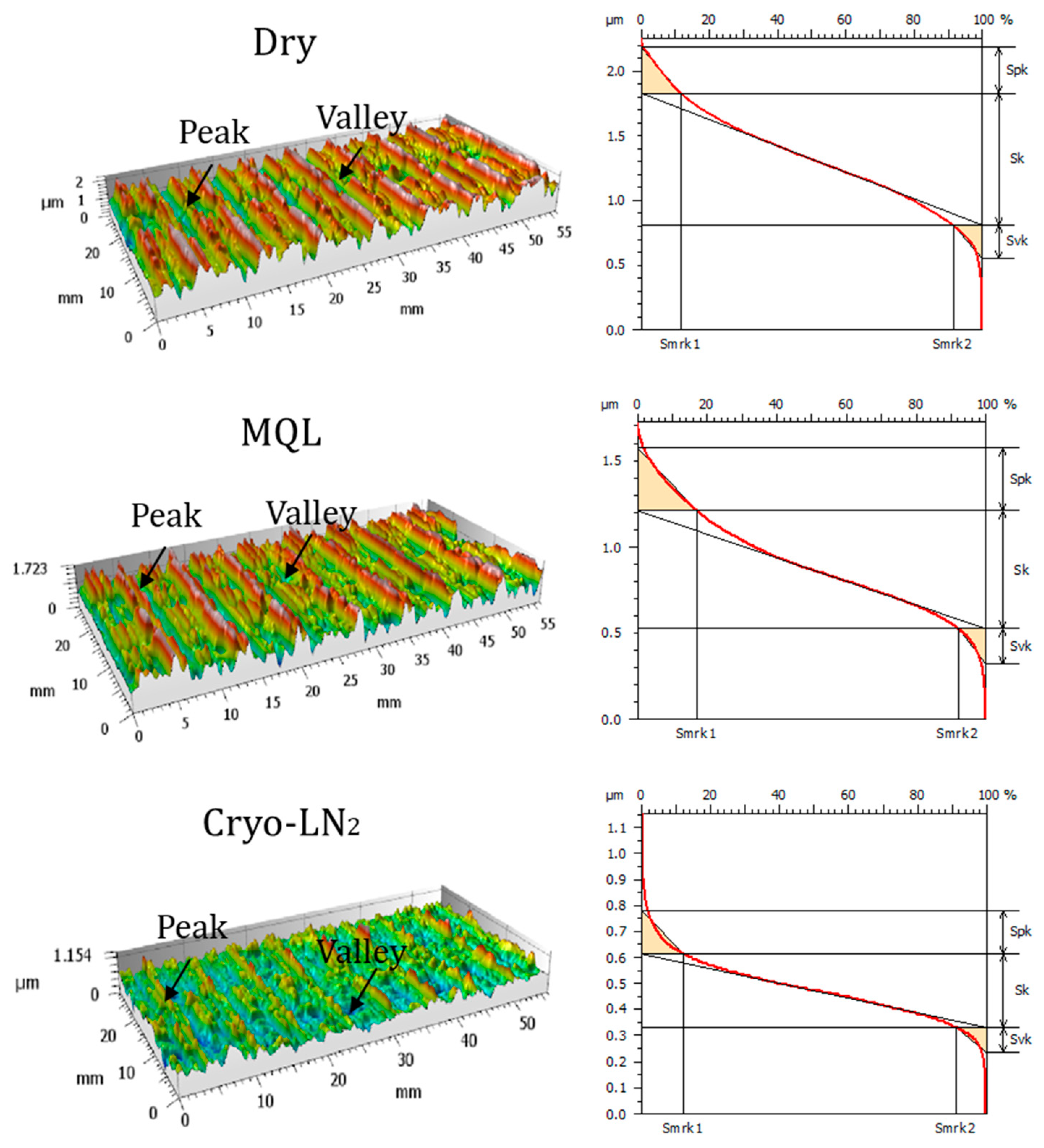

4.1. Surface Roughness

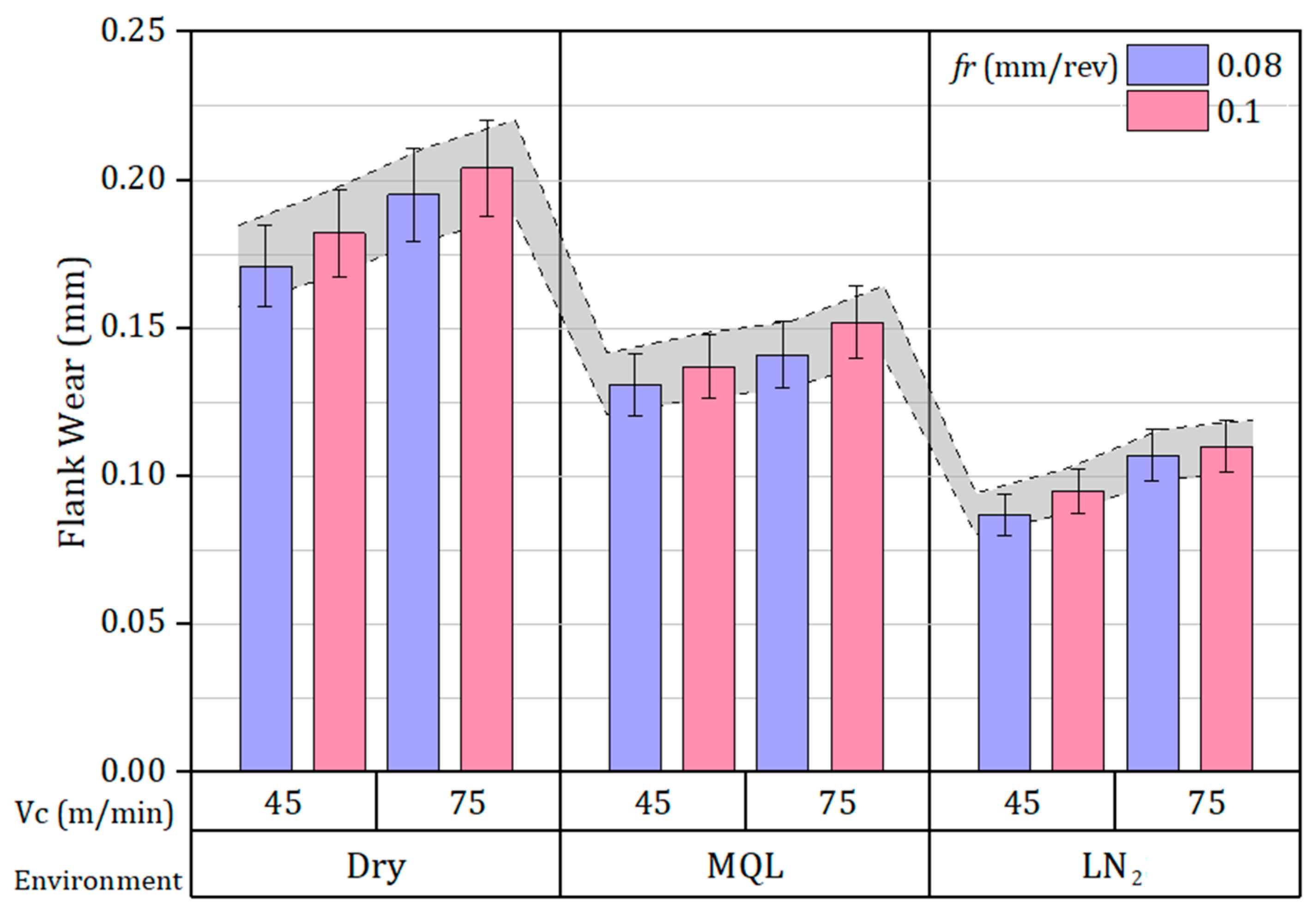

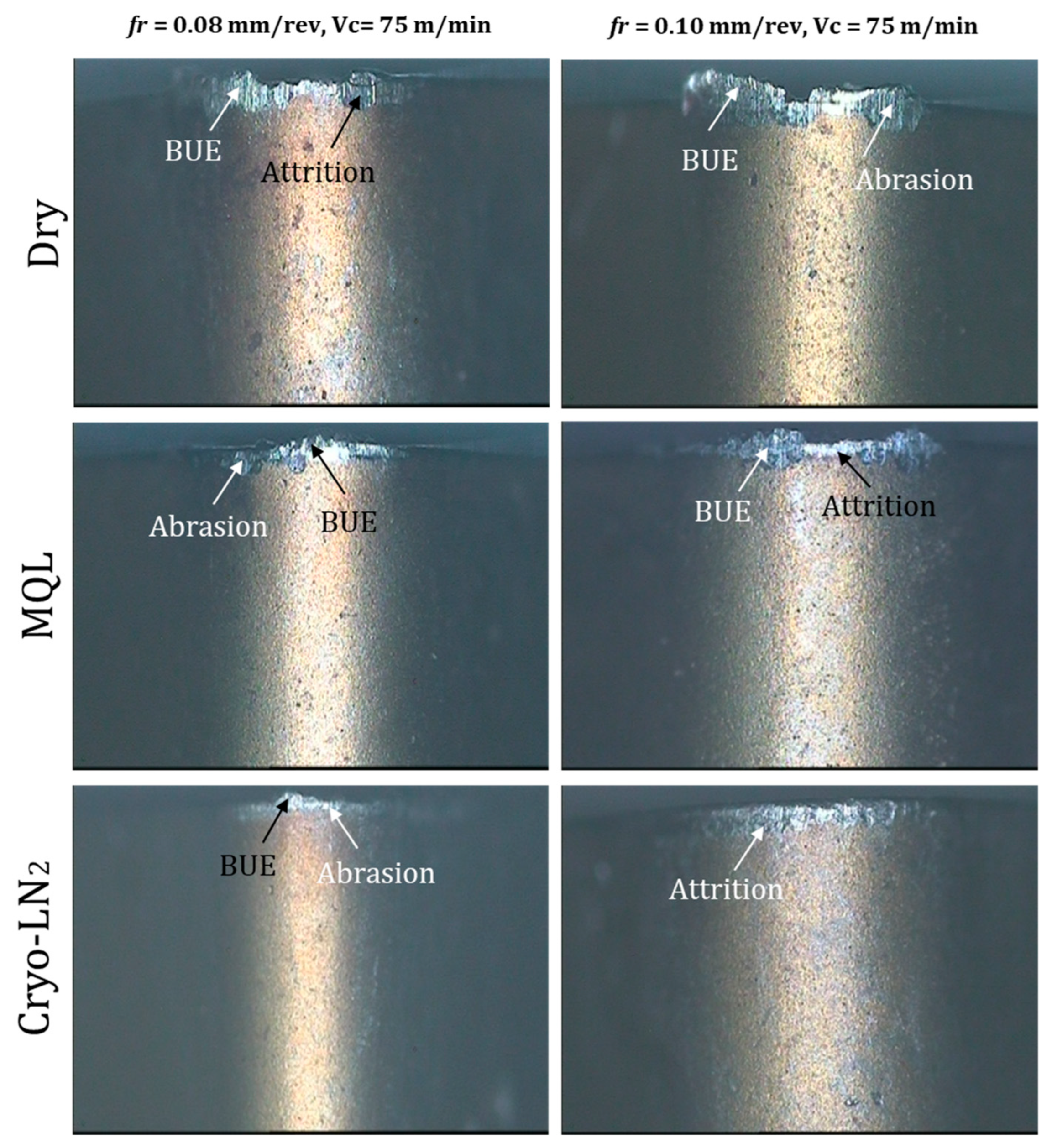

4.2. Tool Wear

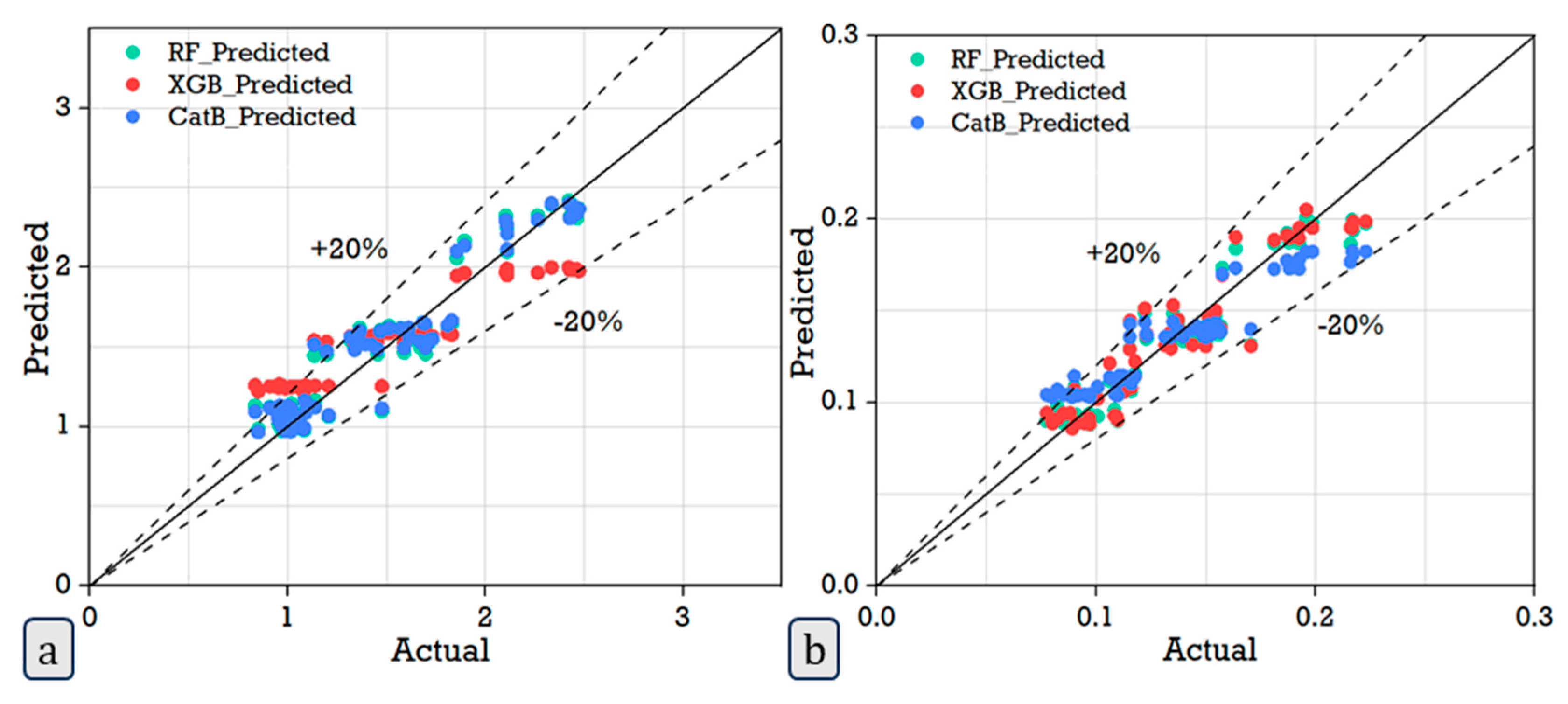

5. Machine Learning

6. Conclusions

- The Ra of the milled LB-PBF AlSi10Mg under all tested speed–feed conditions was found to be lowest for cryo-LN2 (0.98–1.107 μm), followed by MQL (1.448–1.637 μm), and highest for dry cutting (2.028–2.417 μm). Cryo-LN2 was most effective in suppressing thermal softening, allowing for controlled shearing, and hence, the lowest Ra and Sk were obtained.

- The tool wear results showed a significant environmental effect on the Vb, and the dry cutting resulted in the highest wear (0.171–0.204 mm), while the MQL significantly reduced the wear (0.131–0.152 mm), and the cryo-LN2 had the lowest wear (0.087–0.110 mm). The cryo-LN2 gave the most favorable tool life performance, followed by the MQL, while the dry cutting gave the least favorable tool life performance.

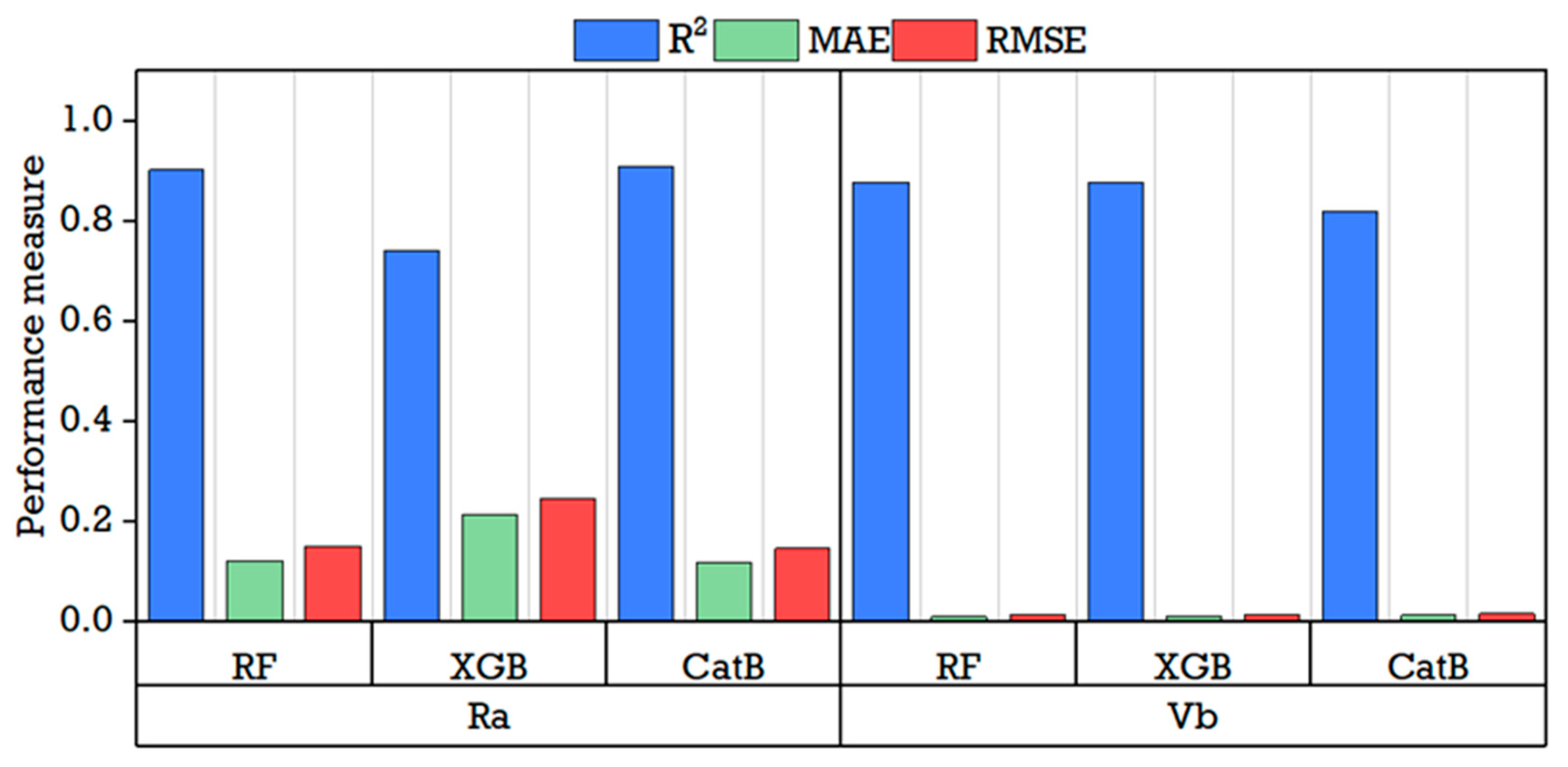

- Data augmentation is applied in this work to ensure the stability of the model training due to the small number of samples, and the dataset is augmented to about 300 observations by applying SMOTE, which generates synthetic samples in order to balance under-represented regions of the feature space. Predictive models for Ra and Vb are developed by utilizing three ensemble learning algorithms, RF, XGB, and CatB, which have shown great performance in the modeling of nonlinear relationships in manufacturing processes.

- CatB yielded the best predictions for Ra, and RF performed closely, while XGB was not the best for Ra. RF and XGB performed very similarly at the top for Vb, and CatB performed poorly. The change of rank between Ra and Vb suggests that the algorithm should be response specific, and therefore, the ensemble methods are very successful in modeling machining responses.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AM | Additive manufacturing |

| Al | Aluminum |

| LB-PBF | Laser beam powder bed fusion |

| MQL | Minimum quantity lubrication |

| ML | Machine learning |

| Ra | Surface roughness |

| Vb | Flank wear |

| Cryo | Cryogenic |

| LN2 | Liquid nitrogen |

| SM | Subtractive manufacturing |

| CFs | Cutting fluids |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| XGB | XGBoost |

| RF | Random forest |

| MLP | Multi-layer perceptron |

| VC | Cutting speed |

| fr | Feed rate |

| DOC | Depth of cut |

| Sk | Core roughness |

| SMOTE | Synthetic minority over-sampling technique |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| RMSE | Root mean squared error |

References

- Li, S.-S.; Yue, X.; Li, Q.-Y.; Peng, H.-L.; Dong, B.-X.; Liu, T.-S.; Yang, H.-Y.; Fan, J.; Shu, S.-L.; Qiu, F.; et al. Development and Applications of Aluminum Alloys for Aerospace Industry. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 944–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouf, S.; Malik, A.; Singh, N.; Raina, A.; Naveed, N.; Siddiqui, M.I.H.; Haq, M.I.U. Additive Manufacturing Technologies: Industrial and Medical Applications. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Yadaiah, N.; Prakash, C.; Ramakrishna, S.; Dixit, S.; Gulta, L.R.; Buddhi, D. Laser Powder Bed Fusion: A State-of-the-Art Review of the Technology, Materials, Properties & Defects, and Numerical Modelling. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 2109–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.; Mehrabi, H.; Naveed, N. An Overview of Modern Metal Additive Manufacturing Technology. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 84, 1001–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, N.S.; Ananth, M.B.J.; Mashinini, P.M.; Ji, H.; Chinnasamy, M.; Palaniappan, S.K.; Gupta, M.K.; Vashishtha, G. Mitigating Tribological Challenges in Machining Additively Manufactured Stainless Steel with Cryogenic-MQL Hybrid Technology. Tribol. Int. 2024, 193, 109343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, M.E.; Waqar, S.; Garcia-Collado, A.; Gupta, M.K.; Krolczyk, G.M. A Technical Overview of Metallic Parts in Hybrid Additive Manufacturing Industry. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, G.; Serjouei, A. Work Hardening for Powder Bed Fusion-Laser Beam (PBF-LB) AlSi10Mg Alloy Manufactured at Different Orientations and Its Application for Vickers Hardness Evaluation. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 138, 1925–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Kruth, J.-P.; Cao, J.; Lanza, G.; Bruschi, S.; Merklein, M.; Vaneker, T.; Schmidt, M.; Sutherland, J.W.; Donmez, A.; et al. Vision on Metal Additive Manufacturing: Developments, Challenges and Future Trends. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 47, 18–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Fu, L.; Xiao, K.; Wang, X. Study of the Material Removal Mechanism and Surface Damage in Laser-Assisted Milling of CF/PEEK. Materials 2025, 18, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, Y.S.; Nguyen, N.; Hosseini, A. Milling of Additively Manufactured AlSi10Mg with Microstructural Porosity Defects, Finite Element Modeling and Experimental Analysis. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 118, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.; Mueller, D.; Kirsch, B.; Greco, S.; Aurich, J.C. Analysis of the Machinability When Milling AlSi10Mg Additively Manufactured via Laser-Based Powder Bed Fusion. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 112, 989–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, B.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, X.; Bai, H. Anisotropy of Additively Manufactured Metallic Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, M.E.; Gupta, M.K.; Ross, N.S.; Sivalingam, V. Implementation of Green Cooling/Lubrication Strategies in Metal Cutting Industries: A State of the Art towards Sustainable Future and Challenges. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 36, e00641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Babu, M.N.; Santhanakumar, M.; Muthukrishnan, N. Experimental Investigation of Copper Nanofluid Based Minimum Quantity Lubrication in Turning of H 11 Steel. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2018, 40, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metla, S.B.S.; Huang, C.-H.; Stachiv, I.; Jeng, Y.-R. Opportunities and Challenges of Minimum Quantity Lubrication as Pathways to Sustainable Manufacturing. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 108272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandan, V.; Naresh Babu, M.; Vetrivel Sezhian, M.; Yildirim, C.V.; Dinesh Babu, M. Influence of Graphene Nanofluid on Various Environmental Factors during Turning of M42 Steel. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 68, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramoni, M.; Shanmugam, R.; Ross, N.S.; Gupta, M.K. An Experimental Investigation of Hybrid Manufactured SLM Based Al-Si10-Mg Alloy under Mist Cooling Conditions. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 70, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebaraj, M.; Kumar, M.P.; Anburaj, R. Effect of LN2 and CO2 Coolants in Milling of 55NiCrMoV7 Steel. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 53, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, N.S.; Srinivasan, N.; Ananth, M.B.J.; AlFaify, A.Y.; Anwar, S.; Gupta, M.K. Performance Assessment of Different Cooling Conditions in Improving the Machining and Tribological Characteristics of Additively Manufactured AlSi10Mg Alloy. Tribol. Int. 2023, 186, 108631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Sinha, A.K. Digital Economy to Improve the Culture of Industry 4.0: A Study on Features, Implementation and Challenges. Green Technol. Sustain. 2024, 2, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-J.; Adityawardhana, Y. Prediction of Mechanical Properties and Fractography Examination of AZ91 Magnesium Composites Reinforced with Graphene Using a Random Forest Machine Learning Model: Experimental Validation. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2025, 25, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omole, S.; Dogan, H.; Lunt, A.J.G.; Kirk, S.; Shokrani, A. Using Machine Learning for Cutting Tool Condition Monitoring and Prediction during Machining of Tungsten. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2024, 37, 747–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-H.; Le, T.-T.; Truong, H.-S.; Le, M.V.; Ngo, V.-L.; Nguyen, A.T.; Nguyen, H.Q. Applying Bayesian Optimization for Machine Learning Models in Predicting the Surface Roughness in Single-Point Diamond Turning Polycarbonate. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6815802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.; Gupta, M.K.; Irfan, S.A.; Ghazali, S.M.; Rathore, M.F.; Krolczyk, G.M.; Alsaady, A. Machine Learning Models for Prediction and Classification of Tool Wear in Sustainable Milling of Additively Manufactured 316 Stainless Steel. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, A.A.G.; Manimaran, G.; Ross, N.S. A Comprehensive Assessment of Coconut Shell Biochar Created Al-HMMC under VO Lubrication and Cooling—Challenge towards Sustainable Manufacturing. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 9059–9075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anburaj, R.; Pradeep Kumar, M. Influences of Cryogenic CO2 and LN2 on Surface Integrity of Inconel 625 during Face Milling. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2021, 36, 1829–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, M.P.; Pelaingre, C.; Delamézière, A.; Ayed, L.B.; Barlier, C. Machine Learning Models for Surface Roughness Monitoring in Machining Operations. Procedia CIRP 2022, 108, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Miao, E.M.; Wei, X.Y.; Zhuang, X.D. Robust Modeling Method for Thermal Error of CNC Machine Tools Based on Ridge Regression Algorithm. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2017, 113, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Qi, J.; Xu, X.; Yang, S. Machining Quality Prediction of Multi-Feature Parts Using Integrated Multi-Source Domain Dynamic Adaptive Transfer Learning. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 90, 102815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, N.S.; Rai, R.; Ananth, M.B.J.; Srinivasan, D.; Ganesh, M.; Gupta, M.K.; Korkmaz, M.E.; Królczyk, G.M. Carbon Emissions and Overall Sustainability Assessment in Eco-Friendly Machining of Monel-400 Alloy. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 37, e00675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Milling Setup | Feeler FV 1000 |

|---|---|

| Material (W/p) | AlSi10Mg |

| Measurement (cm) | 10 × 5 × 1 |

| Insert (tool) coating | CVD-AlTiN |

| Model | APMT |

| Vc (m/min) | 45–75 |

| fr (mm/rev) | 0.08–0.10 |

| Radial DOC (mm) | 12 |

| Axial DOC (mm) | 1 |

| Length of cut (mm) | 20 (4 passes) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Dou, Z.; Guo, K.; Sun, J.; Huang, X. Ensemble Machine Learning for Predicting Machining Responses of LB-PBF AlSi10Mg Across Distinct Cutting Environments with CVD Cutter. Coatings 2026, 16, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010022

Zhang Z, Dou Z, Guo K, Sun J, Huang X. Ensemble Machine Learning for Predicting Machining Responses of LB-PBF AlSi10Mg Across Distinct Cutting Environments with CVD Cutter. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zekun, Zhenhua Dou, Kai Guo, Jie Sun, and Xiaoming Huang. 2026. "Ensemble Machine Learning for Predicting Machining Responses of LB-PBF AlSi10Mg Across Distinct Cutting Environments with CVD Cutter" Coatings 16, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010022

APA StyleZhang, Z., Dou, Z., Guo, K., Sun, J., & Huang, X. (2026). Ensemble Machine Learning for Predicting Machining Responses of LB-PBF AlSi10Mg Across Distinct Cutting Environments with CVD Cutter. Coatings, 16(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010022