1. Introduction

Plasma modification is widely used to modify the surface properties of polymer films, thereby improving the performance of packaging and self-adhesive materials based on them [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Improved adhesive properties ensure stronger adhesion of the material to other surfaces, preventing defects and failures in adhesive joints [

12,

13,

14,

15].

The main issue with using polyethylene (PE) materials in waterproofing is poor adhesion between the PE surface and the adhesive compositions and the pipeline metal substrate. Poor adhesion between the layers of the waterproofing coating prevents the achievement of the required physical and mechanical properties. This reduces service life below standard, thereby increasing the economic costs of re-insulation during major repairs. Currently, experience exists with adhesives containing solvents and modifiers that facilitate diffusion of polyethylene into the adhesive components, thereby enhancing interfacial bonding between the layers. However, it should be noted that the use of modifiers and solvents can negatively affect the strength of the adhesive bond between the polyethylene film and the adhesive. The volume of the adhesive decreases due to solvent evaporation during application and pipeline operation, resulting in cracking and reduced bond strength between the waterproofing layers. When waterproofing coatings are used alongside electrochemical protection methods, a drop in the pipe-to-ground potential can occur, leading to coating peeling from the pipeline surface. Therefore, it is essential to develop a polymer-based adhesive insulating tape that provides strong interlayer adhesion without the need for solvents or modifiers. This material should meet reliability requirements, even if it slightly increases cost and material consumption.

Modification of the surface of polymeric materials using an atmospheric-pressure gliding arc plasma (GAP) is a rapidly developing field. This technology enables targeted modification of the surface’s physicochemical properties without affecting the material’s bulk characteristics, which is especially important for applications in the light, medical, and packaging industries. This process occurs in a plasma, a partially ionized gas containing energetic particles. The plasma flow contains electrons, ions, UV photons, free atoms, radicals, and other active particles [

16].

Currently, various types of electrical discharges are used to modify polymeric materials, including glow, corona, and gliding arc discharges [

17,

18,

19]. During the modification process, surface cleaning effects are observed due to UV radiation, which breaks the organic bonds of contaminants and improves surface adhesion [

20]. Installations for plasma modification of polymeric materials can be divided into three main types, depending on the type of electric discharge used: vacuum glow-discharge installations, corona-discharge installations, atmospheric glow-discharge installations, and gliding-arc installations. The latter type of installation is similar to the first one; however, discharges in these installations occur at pressures close to atmospheric, so there is no need for vacuum systems, and an electrode system replaces the discharge system.

Fedosov et al. [

21] described the installation of glow discharge in a vacuum, developed by B.L. Gorberg from the Ivanovo Research Institute of Electromechanics and Mechanics and Mathematics. The UPH-140 installation is designed to modify polymer films, fabrics, and fibers via glow discharge. It consists of the following central units: a rolling and unrolling chamber, a working chamber, an electrode system, a power source, a gas inlet system, and a vacuum pump. Material modification is carried out in the working chamber at ~80 Pa, with a continuously operating vacuum system. The material to be modified is located between a group of electrodes connected to a power source. A glow discharge is initiated between the electrodes, thereby modifying the material’s surface over an area of 140 cm. The nature of the glow discharge necessitates a vacuum system in these installations. It imposes several technological limitations, including the need to modify the reaction chamber to match its size and to maintain a vacuum throughout the modification process. To maintain pressure in the range of 50–200 Pa, expensive oil forevacuum pumps are required. The unit’s housing must also be strong enough to withstand atmospheric pressure without deforming.

Units using corona discharge for modification have also found industrial applications. It is known that the use of corona discharge for the modification of the surface of films occurs in two different environments: oxygen-containing and oxygen-free [

22,

23,

24]. For this purpose, they used a nitrogen-filled chamber to displace oxygen. The results showed an increase in the polymer film’s wetting angle and in the adhesion work in both environments. For example, when corona is applied in an air environment, the contact angle of wetting decreased to 38.2° compared to the initial 63°. An example of a unit for modifying polymeric materials is the unit patented by Zuev [

25]. The system employs corona discharge to modify the surface of polymer products, thereby improving the interaction between the adhesive and the substrate. This system operates by injecting air into the interelectrode gap between the rod electrodes to deflect the flow of charged particles generated by corona discharge. Gas is then injected from a voltage-generating unit via a gas supply tube in an arc toward the surfaces being modified. This setup allows varying the plasma beam projection length by regulating the airflow at a distance of 30–50 mm from the electrode plane. The plasma beam consists of a multitude of microcharges-streamers initiated between the electrodes under the influence of an applied voltage of the order of U ≈ 20 kV with a frequency of f = 20 kHz. However, the presented setup has a characteristic feature: both modified and unmodified areas are observed on the modified polymer materials. This phenomenon is caused by the non-uniformity of the corona discharge, consisting of a multitude of microdischarges-streamers with a diameter of <1 mm [

26]. When interacting with the surface of the modified material, microdischarges-streamers leave local charges on the surface, which attract subsequent discharges, preventing uniform modification of the film surface. An unevenly modified film has insufficient adhesive properties, reducing the material’s performance characteristics.

Development of gliding arc installations is still underway, as not all aspects of their use to modify various materials have been explored. The setup, developed by Kusano [

27] is used to alter the surface of polymer products via a gliding arc, thereby improving adhesion between the adhesive and the substrate. The modification process begins with plasma generated by a plasma source, which is uniformly distributed over the material surface under high-power ultrasonic waves. A high-power acoustic wave generator produces ultrasonic waves. The frequency of the generated waves is f = 20–30 kHz. It is also known to use coaxial plasma torches, in which a low-current discharge initiates in a swirling gas flow [

15,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. A setup with ≤10 kV applied to the cathode of a coaxial plasma torch is described in [

40]. Under the influence of a swirling reaction-gas flow, a low-current discharge propagates along the coaxial electrodes, thereby enabling a stable process for modifying the surfaces of polymeric materials and polyolefins. Another advantage of using a coaxial plasma torch is the reduction in energy costs and reaction-gas consumption. Coaxial plasma torches are adaptable to various gases (nitrogen, argon, hydrogen, oxygen, helium, and mixtures thereof) and polymeric materials, making them versatile across industries.

Based on the reference, it can be concluded that the structural components of installations for modifying the surface of polymeric materials using an electric discharge consist of an electrode system, a power source, and a gas system. Polymer films, either as individual sheets or rolls, are placed between electrodes with an adjustable air gap, where a high-voltage electrical discharge initiates plasma modification. The scientific hypothesis is that modifying the surface of polymer films using a GAP can alter their structural, morphological, and physicochemical properties and, consequently, increase adhesion.

The advantage of this GAP configuration over corona or dielectric barrier discharges is that, in the optimal mode, the film surface temperature does not exceed 65–70 °C, thereby preventing shrinkage and deformation of 100-μm-thick polyethylene films. It is a common problem in corona systems, in which local heating can readily reach 100–130 °C. Because of the self-cleaning nature of the gliding arc, the electrodes are virtually unaffected by polymer dust contamination, and the system can operate continuously for hundreds of hours without requiring cleaning, unlike either corona wires or dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plates. In addition, the active plasma zone in GAP configuration covers 80–120 mm in width in a single pass and can be easily scaled by simply adding modules, whereas the treatment width of corona treaters is typically limited to 40–60 mm and that of DBD is even smaller. The energy consumption required to achieve the same level of adhesion with a gliding arc is 2–3 times lower than with corona discharge.

This work aims to improve the adhesive properties of PE materials in waterproofing compositions for metal substrates. A method for plasma modification of the PE surface, which involves bombarding the surface with charged particles accelerated by an electric field, is proposed in this work. During plasma modification, a layer of active centers, including hydroperoxide (-OOH), hydroxyl (-OH), and carboxyl (-COOH) functional groups, forms on the PE surface. An increase in roughness is observed, which improves mechanical adhesion and promotes adhesive placement on the PE surface, thereby increasing the strength of adhesive joints [

41]. Another advantage of this method is the ability to modify the surface without changing the original strength and optical properties of PE [

42,

43,

44].

2. Materials and Methods

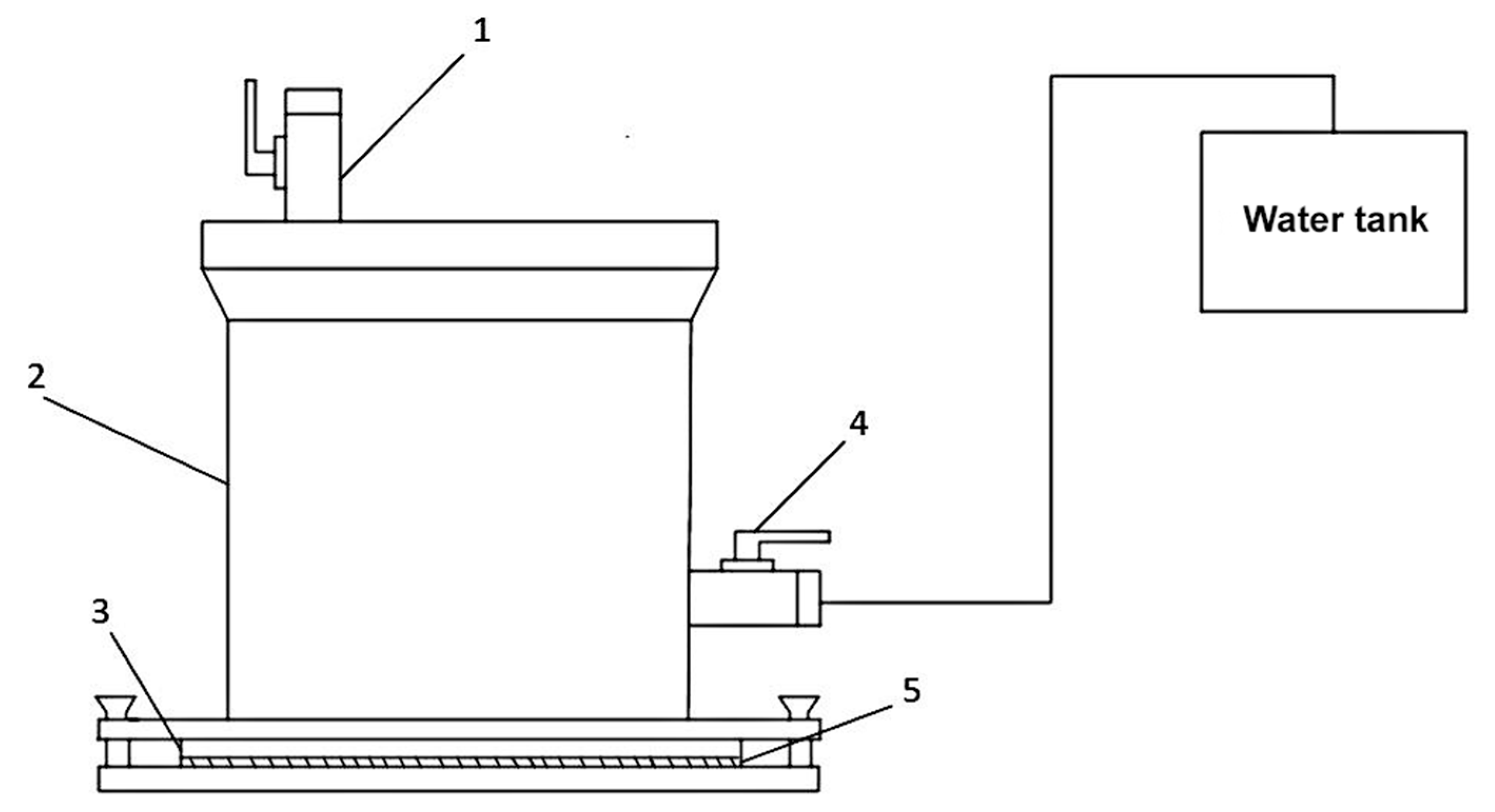

2.1. Gliding Arc Plasma Setup and Treatment Parameters

PE films with a thickness of 100 µm, manufactured in accordance with GOST 10354-82 “Polyethylene film”, were used as the test material [

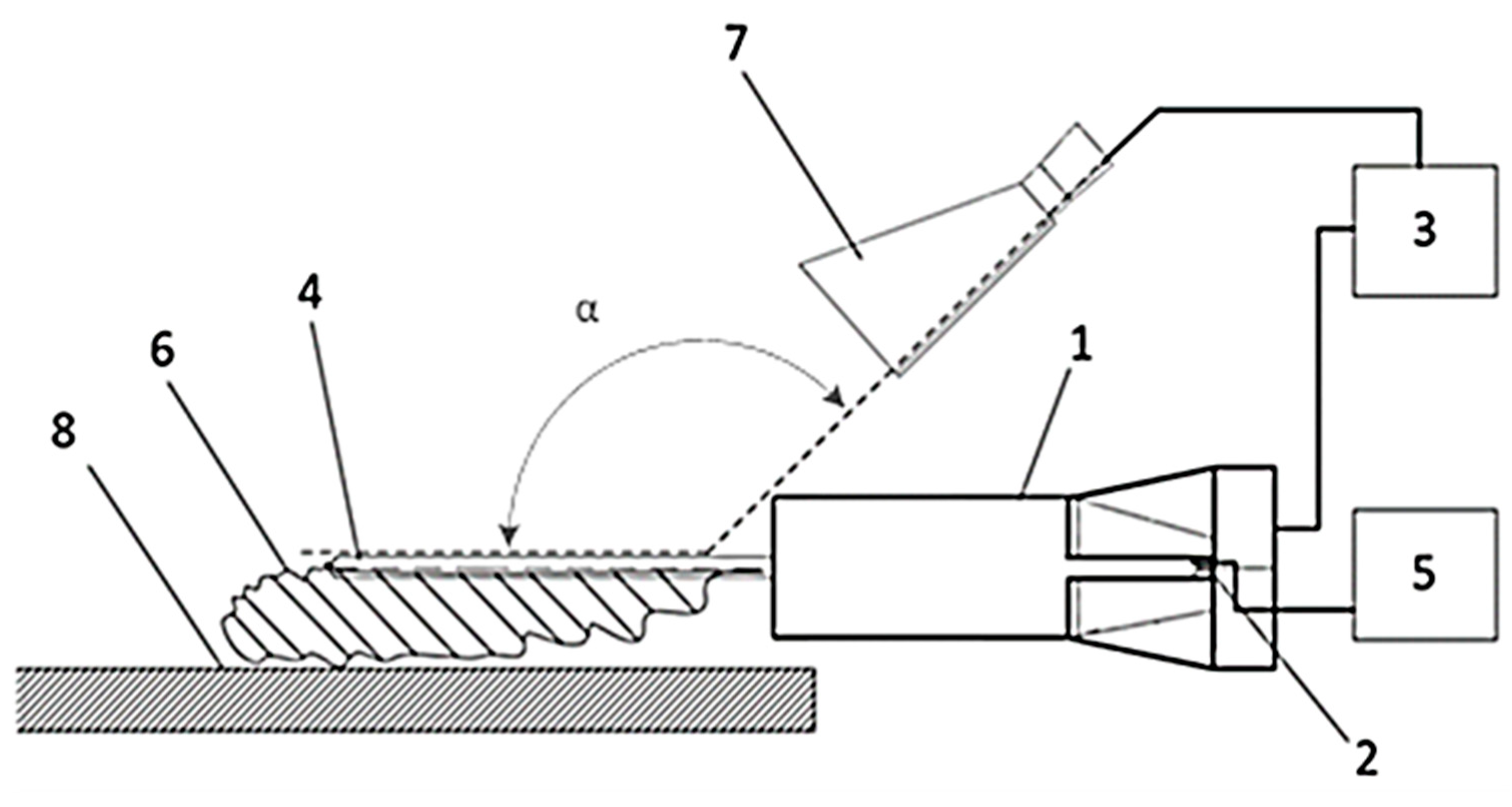

45]. To improve the adhesive properties of PE films and create a waterproofing coating with an extended service life, a surface modification setup for polymer film treatment in atmospheric-pressure GAP was developed (

Figure 1) [

46].

In the developed setup, the electrodes are equipped with seed protrusions. By adjusting the position of the hinged tube connected to the reaction gas inlet system, the diverter’s position relative to the electrode plane can be adjusted. Varying the reaction gas flow angle α of the diverter controls the area of surface modification on the polymer film.

The distance between the electrodes was adjustable from 5 to 15 mm. Polymer film surface modification was performed for up to 60 s at a pulse voltage of 8 kV, a current of 40 mA, and a frequency of 15 kHz. The deflector nozzle angle of attack was α = 115–160°. The distance between the polymer film and the electrode plane was 15 mm, preventing short circuits and eliminating thermal effects from the electrodes on the polymer film.

When studying the change in adhesion properties depending on the operating modes of the gliding arc setup, the angle of attack of the reaction gas α, the contact area of the plasma (S) of the gliding arc, and the volume flow rates of the main (M) and deflecting (F) air flows were adjusted. An increase in

M,

F, and the angle α grows the contact area S. Its highest value S = 27.3 cm2 is achieved at an angle α = 160° with a mass flow rate of the reaction gas (air)

M = 100 L/min and

F = 80 L/min. It was found that during the GAP modification of PE films at a specific modification power of Wspec < 19 W/cm2, the electrode temperature did not exceed 60–70 °C, and no signs of shrinkage were observed. At Wspec > 24 W/cm2, shrinkage of the samples is observed at an electrode temperature of 150–160 °C, as monitored using a Shot Pro thermal imager (Seek Thermal Inc., Santa Barbara, CA, USA).

2.2. The Approaches for Surface Investigation, Physical and Chemical Properties of PE Films

To study the surface adhesion properties of the modified PE film, the sessile drop method was used on a setup equipped with a Levenhuk DTX 90 digital microscope (Levenhuk, Inc., St. Petersburg, Russia) and ToupView software (Windows Microscope ToupView Package 15 January 2025). Distilled water was used as a working liquid for the contact angle test. The method and setup are described in more detail in a previous work [

47].

A multivariate statistical analysis was conducted to determine the optimal conditions for PE film modification (deflecting nozzle angle and modification time) to maximize surface adhesion properties measured by the sessile drop method. A two-factor factorial experimental design was used for calculations.

The composition of the functional groups formed on the surface of the polymer films after plasma modification was determined using an ALPHA infrared (IR) spectrometer with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) attachment (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) (incidence angle was 45°, 24 scans, resolution 4 cm

−1). All spectra were automatically baseline-corrected using the concave rubber-band method (64 points) implemented in OPUS software (

https://www.bruker.com/en/products-and-solutions/infrared-and-raman/opus-spectroscopy-software.html (accessed date 25 November 2025)) and normalized to the intensity of the internal standard band at 2919 cm

−1 to compensate for slight variations in sample–crystal contact pressure. Qualitative and quantitative elemental analysis, along with the study of the supramolecular structure of the films, were performed on a JSM-6510LV (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) scanning electron microscope (SEM) with an INCA Energy 350 (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK) microanalysis system or energy dispersive system (EDS) and a JFC-1600 desktop setup (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at the Science Center “Progress” of the East Siberia State University of Technology and Management, Ulan-Ude, Russia (ESSUTM). The SEM acceleration voltage was 15 kV. Surface roughness and local physicochemical properties were studied using a Multimode 8 Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany).

To study the electret properties, an IPEP-1 device (MNIPI JSC, Minsk, Republic of Belarus) was used according to the user manual guide described in USHY 411153.002 RE [

48]. The electric charge density measurement range was 0.02–10 μC/m

2. The surface potential (

Ve), electric field strength (

E) and surface charge density (

σeff) of the samples were determined with a measurement error of no more than 3%. The IPEP-1 device operates by periodically scanning a receiving electrode at a specified distance from the sample surface.

The formation of an electret layer in a modified polymer film occurs as a result of the simultaneous occurrence of two physical processes: the deep injection of negative charge carriers from a sliding arc and the induced polarization of the dipole moments of polar functional groups under the action of this injected charge. The resulting macroscopic electric field directs the migration of polar groups toward the surface and significantly slows their thermodynamic relaxation into the bulk of the material.

The electret properties are quantitatively described using three interrelated parameters. The surface potential Ve characterizes the retention energy of polarized groups near the phase boundary: higher absolute values of Ve correspond to smaller contact angles with distilled water and greater long-term stability of the hydrophilic properties. The internal electric field strength E determines the magnitude of the electrostatic component of the attractive force between the modified film and the polar components of the bitumen-polymer mastic, thereby directly contributing to the adhesion work and the strength of the adhesive bond upon peeling. In our experiments, an increase in E by 1 kV/cm was accompanied by an increase in adhesion to the steel substrate by 4–5 N/cm. The effective surface charge density σeff integrally takes into account both the contribution of the charge actually injected from the plasma and the equivalent charge caused by the orientation of the dipoles of the macromolecules. This parameter shows the greatest sensitivity to exceeding the modification time. It begins to decrease statistically significantly even when the GAP modification duration exceeds 10 s, serving as an early indicator of subsequent degradation of wettability and adhesion characteristics, even while maintaining a high total oxygen content in the near-surface layer.

2.3. The Approaches to Measuring the Mechanical Properties of PE Films

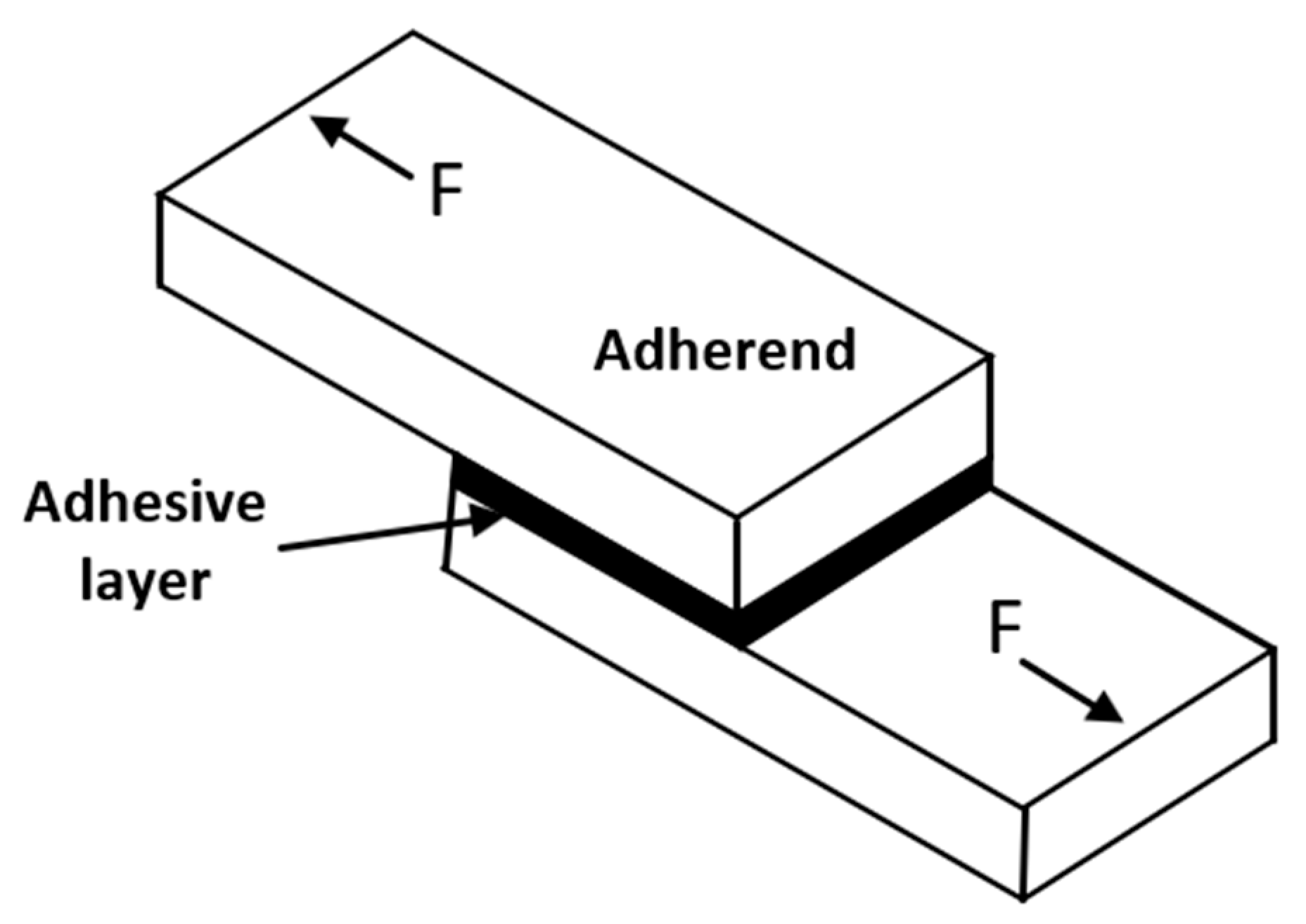

The strength test of the adhesive joint was conducted in accordance with standard methods described in ASTM D1002 “Standard Test Method for Apparent Shear Strength of Single-Lap-Joint Adhesively Bonded Metal Specimens by Tension Loading” and GOST 32316.1–2012 (EN 12317-1:1999) “Flexible bitumen-containing roofing and waterproofing materials: Method for determining the shear strength of adhesive joints” [

49,

50]. The test specimen consisted of two 50 mm-wide polyethylene film strips bonded together in a lap joint with adhesive mastic. The waterproofing sealant “Transkor-Gaz,” a rubber-resin-based mastic produced by JSC “KRONOS SPb” under TU 5775-004032989231-2015 in accordance with GOST R 51164-98 “Steel main pipelines. General requirements for corrosion protection,” was used as the mastic [

51]. The test was performed on an Instron 3367 tensile testing machine (Illinois ToolWorks Inc., Frankfort, IL, USA), compliant with GOST 28840-90 “Machines for testing materials under tension, compression, and bending. General technical requirements” [

52]. At least three specimens were used for the test. The test result was taken as the arithmetic mean of the time-to-failure values for at least three specimens, with a test error of 1%.

3. Results

3.1. Study of the Contact Angle and Adhesion Work of Modified Polymer Films

To confirm changes in contact properties and to quantitatively evaluate the adhesive properties of PE films modified by atmospheric-pressure gliding arc plasma, contact angles were measured. The test was carried out using the “sessile drop” method with an absolute error in determining the contact angle of no more than 0.5°. To assess the reproducibility of contact angle measurements, the arithmetic mean of three measurements was taken as the result. The assessment of the adhesive properties of the modified PE films is presented by a series of measurements of the contact angle value (

Table 1 and

Table 2) depending on the inclination angle of the deflecting nozzle,

α = 115°, 130°, 145°, 160° and the modification time,

t = 0.5, 10, 15, 30, 60 s.

The highest contact angle for PE films,

ϴ = 21–22.5°, was observed at

α = 145° with a modification time of 10 s. The adhesion work (

Wadh) of the modified polyethylene films was determined by calculating the Young–Dupré equation [

53]:

where

γLV is the liquid’s surface tension and

θ is the average contact angle.

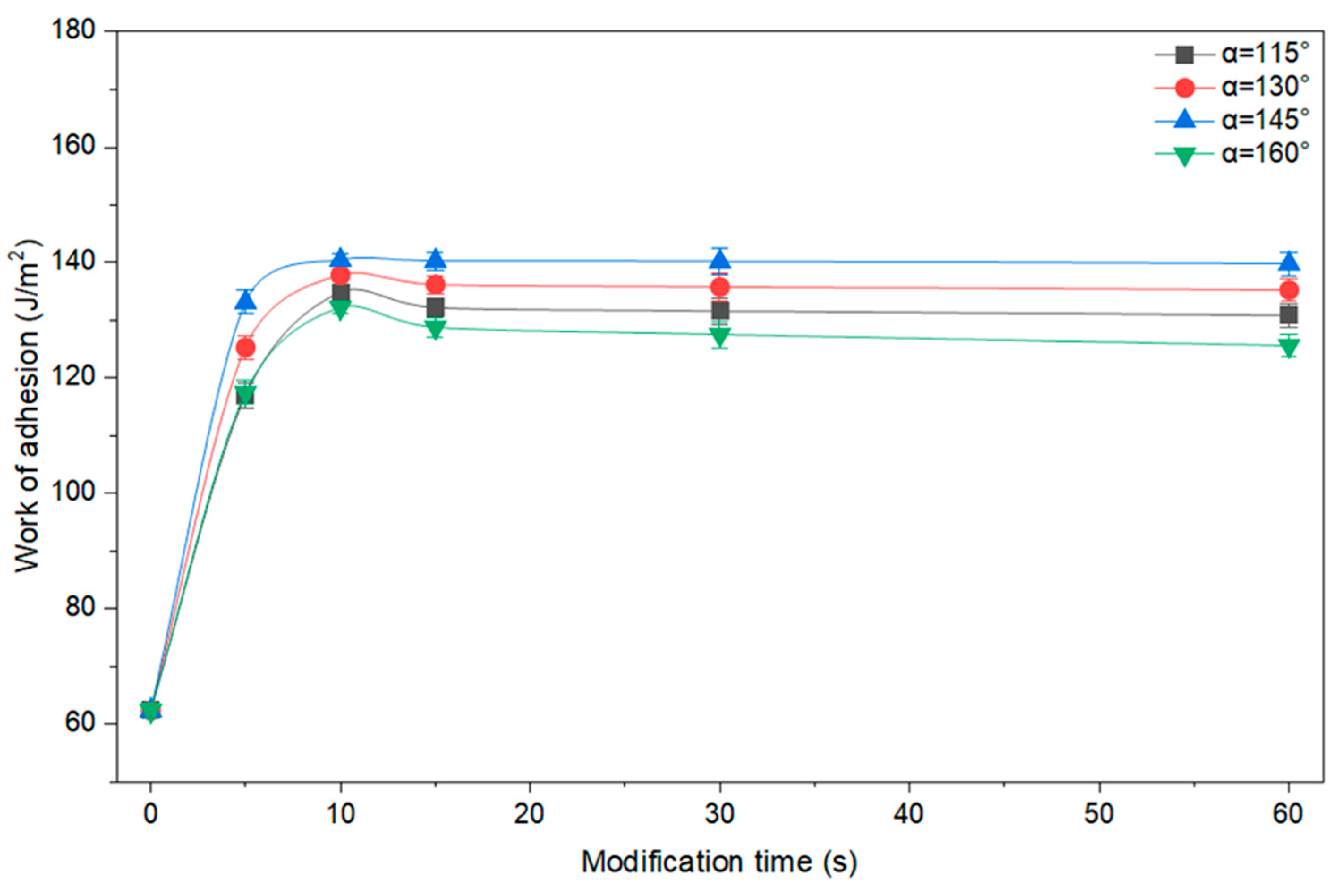

Figure 2 shows the calculated values of the work of adhesion based on the results of a study of the contact angles of PE films before and after GAP modification at angles α = 115–160°.

Depending on the deflecting nozzle angle, the highest adhesion work for PE films

Wadh = 141.3 mJ/m

2 is achieved

α = 145° with a modification time of 10 s. The adhesion work increased by 79.2 mJ/m

2 over the range from 0 to 10 s of modification, starting from an initial value of 62.1 mJ/m

2 for untreated PE. Increasing the PE modification time beyond 15 s does not result in a significant change in the work of adhesion. Therefore, it can be concluded that the adhesion work reaches a steady-state value after 15 s (

Figure 2).

The results obtained are consistent with those reported in [

25,

54], which studied the effect of the afterglow of atmospheric-pressure discharges in an air flow on the adhesive properties of PE films, yielding wetting angles

ϴ = 40 ± 3°. The modification time in this case was 20–60 s. The results of the GAP modification are described in the work [

44], indicating the achievement of a contact angle of

ϴ = 17.9 ± 2.7° with initial values of

ϴ ≈ 72°. The modification was carried out at an airflow rate of 17.5 L/min. The modification improved adhesion characteristics by 3.5–4.7 times.

Current research results are consistent with the literature and experimental data. The GAP modification of PE films for 10–15 s at an angle α of 145° reduces wetting angle ϴ by 4.5 times from 98.3° to 21–26°. This increases the adhesion work Wadh by more than two-fold from 62 mJ/m2 before GAP treatment to 140 mJ/m2 after the aforementioned treatment parameters.

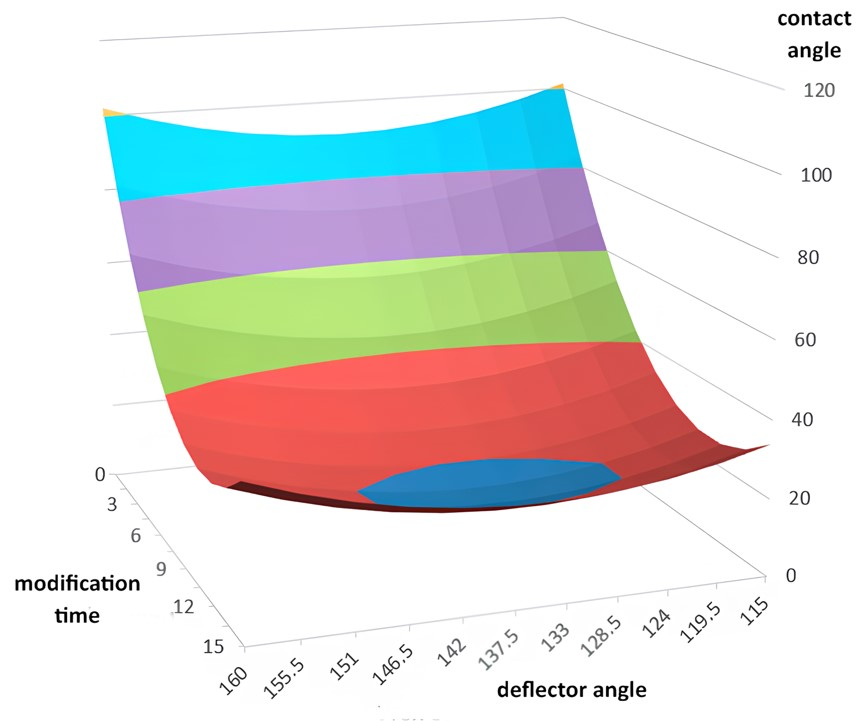

3.2. Optimization of GAP Parameters Through a Two-Factor Regression

Given the need to select optimal modification parameters (deflecting nozzle angle and the modification time) and apply them, it is reasonable to enable multivariate statistical analysis methods. To identify the optimal parameters for modifying films in a GAP, an experimental design approach was employed. Two-factor regression equations and graphical models were created. Using the collected data, regression equations were developed to describe how the contact properties of PE films, specifically the wetting angle, change as a function of the deflecting nozzle angle (

x1) and the modification time (

x2). The measurement ranges were:

x1 = 115–160°, and

x2 = 0–15 s for PE. The response variable was the contact wetting angle (

y1), which ranged from 22 to 98.3° for PE films. Based on the experimental results, planning matrices were prepared for PE films (

Table 2).

The following regression equations were obtained describing the influence of modification time and deflection angle on the contact angle of PE films:

Checking the obtained model for adequacy was calculated using the Fisher criterion. Equation (3) as follows:

where

Sres is the residual dispersion and

Srepr is the reproducibility variance.

Model reliability was assessed using the R2 coefficient, which indicates the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable explained by the model. The R2 value was 0.7114 (71.14%) for Equation (2), indicating good explanatory power. To adjust the R2 coefficient for the number of factors in the model, the adjusted R2 was calculated as 0.6153 (61.53%). The statistical significance of the model as a whole was assessed using Fisher’s F-test at the p < 0.05 significance level. The obtained model was adequate because Ftab (0.05; 3; 5) was equal to 5.41, which is greater than Fobs.

The resulting model reflects the process as shown in

Figure 3. The optimal GAP modification for PE films is 10–15 s at an angle

α of 130–145° to obtain a wetting angle

ϴ < 26°.

The response variable was the surface adhesion work (

y2) of the films, ranging from 62.4 to 140.3 mJ/m

2 for PE films (

Table 2). The following regression equations were obtained describing the influence of modification time and deflection angle on the surface adhesion work of PE films Equation (4):

The R2 value was 0.7135 (71.35%) for Equation (4), indicating good explanatory power. To adjust the R2 coefficient for the number of factors in the model, the adjusted R2 was calculated as 0.6180 (61.80%). The statistical significance of the model as a whole was assessed using Fisher’s F-test at the p < 0.05 significance level. The obtained model was adequate according to the Fisher criterion because Ftab > Fobs (5.41 > 0.01), and the p-value for the model was below the selected significance threshold.

Based on the calculated data, to achieve an adhesion work of value (

Wadh) greater than 130 mJ/m

2 on the PE surface, the optimal modification conditions for PE films were determined to be a 10 s treatment and a deflection angle of 135° (

Figure 4).

3.3. Study of Physicochemical Properties of Modified Films of Primary Polyethylene

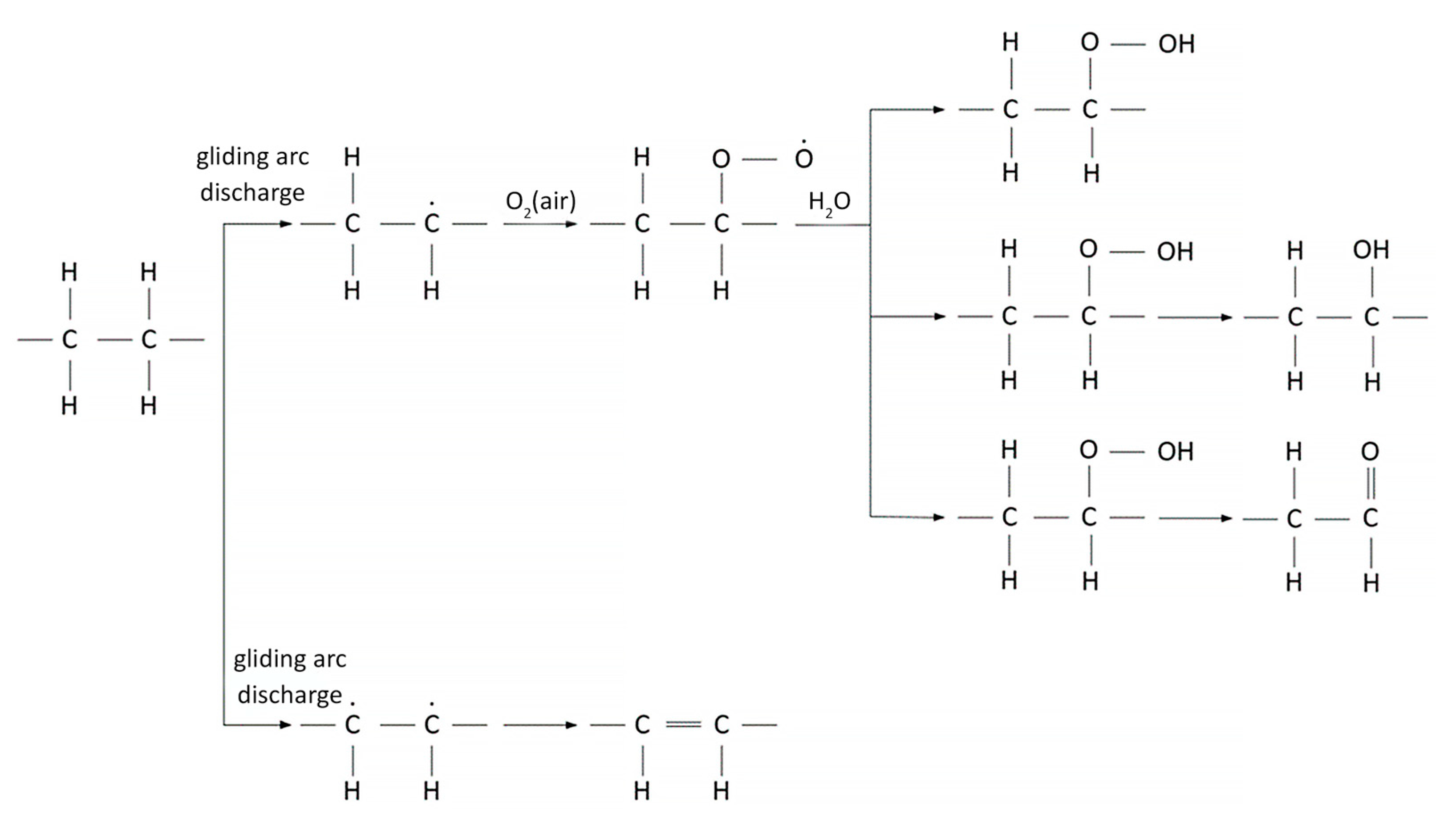

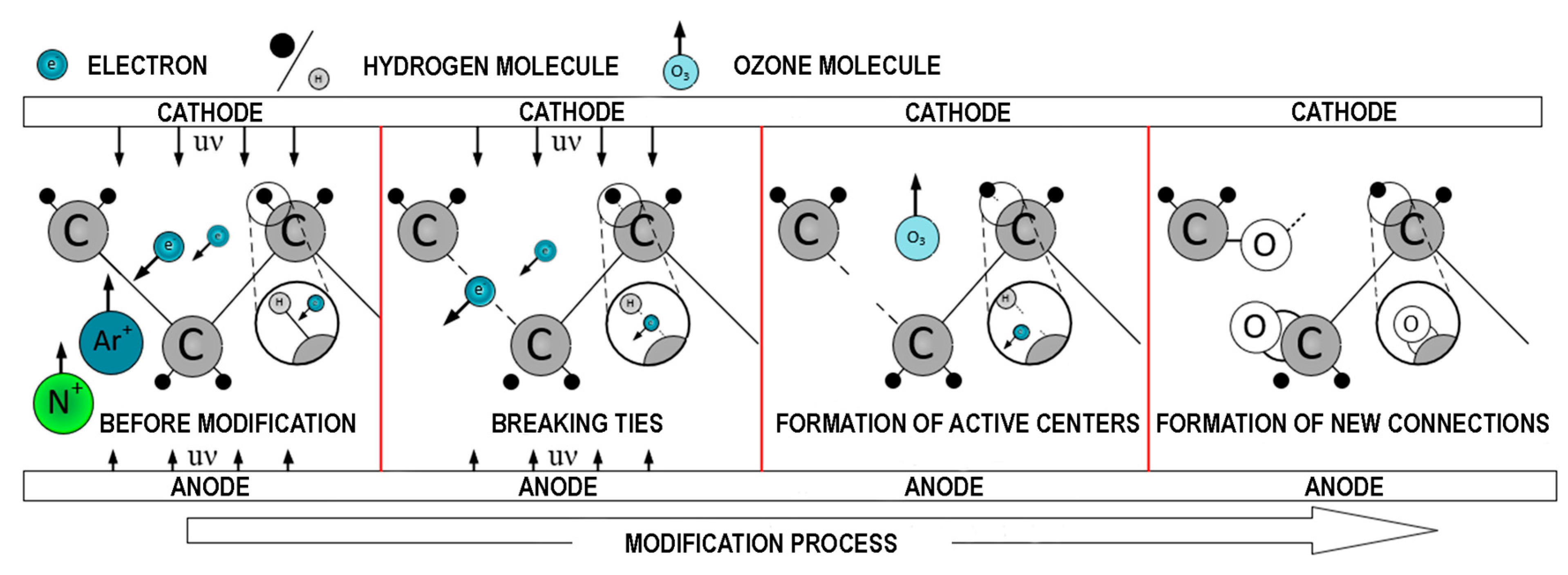

When plasma interacts with the polymer surface, the gas is ionized, generating free electrons. These electrons have high energy and can transfer it to polymer molecules. This leads to molecular excitation and the formation of radicals, which react with other polymer molecules, forming new chemical bonds. Thus, the transfer of electron energy to polymer molecules is the primary mechanism of plasma-induced activation of the film surface.

A decrease in the contact angle of modified PE films and an increase in surface energy are associated with changes in the polymer film’s structural and chemical composition. For example, during analysis of changes in the chemical composition of plasma-modified PE, peaks at 908 and 966 cm

−1 were observed [

55]. This is attributed to the formation of double bonds of the type RCH=CH

2 and R1CH=CHR

2. The broad band in the 3130–3540 cm

−1 region is due to groups that form molecular hydrogen bonds. It was noted that modification in oxygen plasma and O

2-Ar mixtures leads to the formation of oxygen-containing functional groups on the PE surface: carbonyl compounds (1570–1800 cm

−1) and hydroxyl groups (3120–3570 cm

−1).

The PE surface structure before and after modification was studied using ATR IR spectroscopy, revealing changes in the spectral parameters of functional groups under the influence of temperature, irradiation, and other factors (

Figure 5). The formation of new functional groups—hydroxyl (-OH), carboxyl (-COOH), and hydroperoxide (-OOH)—was observed in the IR spectra of the PE films.

The IR spectrum of unmodified PE films shows absorption bands related to stretching (2919 and 2845 cm

−1), deformation (1461 cm

−1—crystalline phase), and rocking (718 cm

−1) vibrations of CH

2 groups (

Figure 5). All spectra are baseline-corrected (concave rubber-band method) and normalized to the intensity of the CH

2 asymmetric stretching band at 2919 cm

−1. The intensity of the broad O–H/OOH stretching band (3100–3600 cm

−1) reaches its maximum after 10 s of treatment and slightly decreases at longer times due to surface etching. The same trend is observed for the carbonyl region (1700–1750 cm

−1).

When the polymer film is exposed to GAP, chemical bonds are broken. The modified surface then oxidizes in the presence of ozone produced during plasma combustion. After a 5 s modification of the polymer films, absorption bands appear in the range from 3600 to 3000 cm

−1, characteristic of deformation vibrations of hydroxyl OH and OOH groups, and in the 1200–1000 cm

−1 region, indicating vibrations of C-O groups, which show surface oxidation. A 10 s modification of PE films results in absorption bands in the 1300–1100 cm

−1 range, caused by vibrations of CH

2 and ν(C-C) groups. Bands above 3000 cm

−1 confirm the presence of OH groups, while C=C and C=O groups appear in the 1700–1650 cm

−1 region. The absorption observed in the 1200–1000 cm

−1 range indicates stretching vibrations of C-O groups. Increasing the exposure time to 15 s results in a decrease in the absorption bands observed for PE films (

Figure 5).

Increasing the modification time of samples in a non-monotonic manner increases the relative intensities of the hydroxyl and carbonyl group bands. This occurs because plasma modification etches the polymer surface, followed by oxidation driven by UV radiation and by ion bombardment with O atoms, O

2+, and O

3 molecules. The relative intensity of the hydroxyl group peaks after 10 s of GAP modification for PE. Extending the modification time of PE films beyond 10 s results in the rupture of macromolecular chains. Based on the data, a diagram illustrating a possible mechanism for PE film surface modification under GAP is shown in

Figure 6.

The increase in the concentration of oxygen-containing surface groups on PE is confirmed by quantitative and qualitative analysis using SEM-EDS (

Table 3).

An increase in the oxygen content to 9.2% wt for PE indicates improved wettability due to the rise in the concentration of hydroxyl OH groups and oxygen-containing polar functional groups on the surface of the polymer film, which means oxidation of the polymer film surface. The formation of C=C, and COOH groups on the surface of PE films, observed in IR spectroscopy after GAP modification, is also confirmed. With a 5 s modification, absorption bands characteristic of hydroxyl OH groups and C-O-groups are observed in the IR spectra, indicating surface oxidation. Modification of PE films for 10 s leads to the appearance of absorption bands of stretching vibrations of C-O-groups and an increase in the intensity of the absorption bands of OH groups. A 15 s modification further increased the intensity of these absorption bands. When the modification time reaches 30 s, surface etching is observed. During which the breakdown of the molecular chain occurs, characterized by a decrease in the intensity of the described absorption bands. This correlates with the IR spectroscopy results.

Based on the obtained data, it was shown that when exposed to low-temperature GAP, the following chemical processes occur on the surface of PE films: an increase in the concentrations of unsaturated chain fragments, carboxyl, hydroperoxide, and hydroxyl groups.

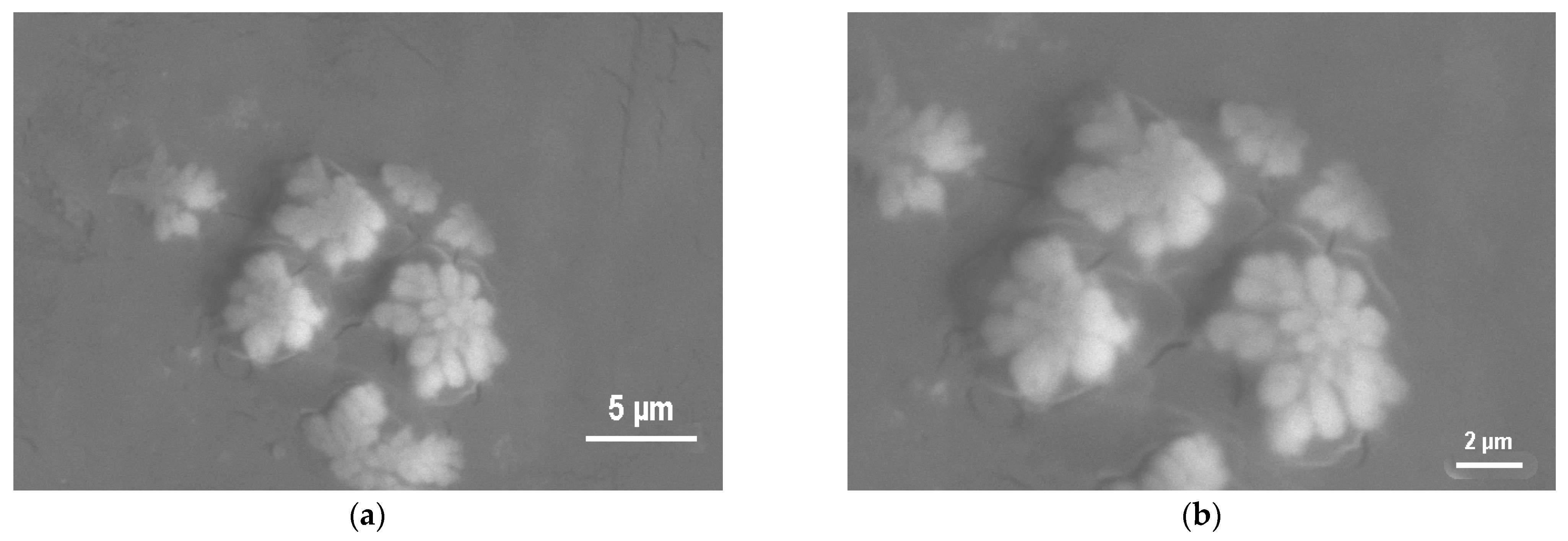

3.4. Study of the Surface Microstructure of Modified Polymer Films Using SEM

The SEM study of the supramolecular structure provides a clear picture of the morphology of the crystalline regions and the supramolecular organization of the PE films before and after atmospheric-pressure GAP modification (

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). The remaining volume is filled with macromolecules or macromolecular segments that are not integrated into the crystallite and do not form ordered structures. Polycrystalline structures, known as spherulites, and crystalline formations, called dendrites, are observed on the surface. The presence of spherulites (

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10) influences the mechanical (strength) and other properties of polymers. For instance, the opacity of polyethylene, nylon, and other crystalline polymers is caused by the presence of spherulites. The variety of supramolecular structures is the primary reason for the unique properties of crystalline polymers.

The surface of the untreated PE is smooth with minimal relief elements. Individual small casting defects and rare microcracks formed during film production are visible. The crystalline supramolecular structure is poorly defined: only the beginnings of lamellar formations and small spherulite-like aggregates less than 1–2 µm in size are visible. The boundary between the crystalline and amorphous regions is blurred and the interphase area is small. This is the typical morphology of industrial PE film produced by extrusion followed by rapid cooling, which suppresses crystallization.

During the 5 s modification, a rise in small crystallites (1.5–2 μm) is observed in PE, expanding the interface area between the crystalline and amorphous phases (

Figure 8). A short treatment (5 s) leads to surface activation and initial recrystallization. The number of charge traps at the crystallite/amorphous phase boundary increases, thereby significantly improving the electret characteristics and adhesion performance, as discussed in more detail in the following sections.

A 10 s GAP modification results in increased spherulitic and dendritic structure sizes (5–10 μm), thereby increasing the interphase boundary area, which is favorable for superior adhesion (

Figure 9). The surface is covered with well-developed spherulites and dendritic crystalline formations up to 5–10 μm with no excessive etching traces. The spherulites have a distinct radial lamellar structure with clearly defined interlamellar amorphous layers. Such a developed morphology, with lamellae protruding above the amorphous regions, creates “microanchors” for mechanical adhesion of the adhesive. The optimal ratio of chemical functionalization (maximum –OH and –COOH groups) and physical activation (maximum interphase boundary area and developed microrelief) is achieved, maximizing adhesion work (141.3 mJ/m

2) and mechanical properties (shear strength and adhesion force to the steel substrate).

Further growth of crystalline formations occurs with a 15 s modification, but at the expense of negative consequences (

Figure 10). Spherulites enlarge to 10–15 µm or more, and begin to merge, forming large dendritic aggregates. Due to prolonged thermal exposure (local heating to 60–70 °C) and intensive etching, partial melting and smoothing of the microrelief are observed: protruding lamellae tighten and the height of irregularities decreases. Signs of thermal degradation appear—microcracks along the boundaries of large spherulites and zones of localized destruction of the amorphous phase. The interphase boundary area begins to decrease due to crystallite coarsening and a decrease in the number of crystallites per unit area. Such crystallite growth causes internal stresses and shifts the fracture zone toward the interphase boundary, ultimately decreasing the strength of the adhesive bond during delamination.

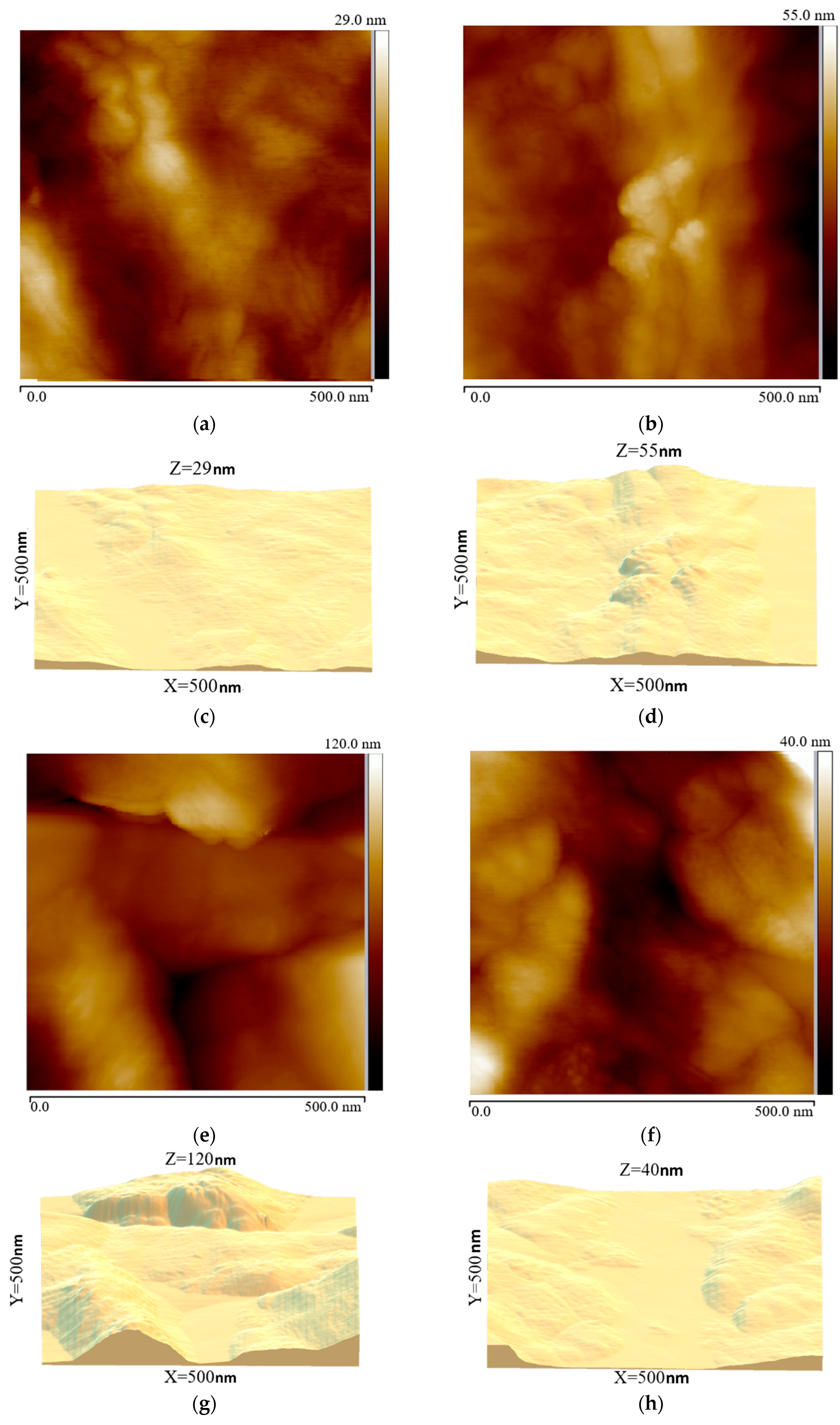

To evaluate the physico-mechanical properties, AFM was employed to estimate the phase interface area.

3.5. Surface Investigation of Modified Polymer Films Using AFM

AFM was used to examine the surface microrelief of 100-μm-thick modified PE films before and after modification. For comparison with GAP modification, a chemical modification was conducted. It aims to alter the surface chemistry of a polymer by introducing new functional groups or other surface structures. Chemical modification was discussed in [

56,

57,

58,

59]. According to chemical bond theory, the reactive components in the adhesive and the substrate interact with each other to form chemical bonds.

A method for treating the surface of PE and polypropylene films in a solution of sulfuric acid and sodium dichromate was proposed in [

35]. Before treatment, the film surface is degreased with acetone or xylene. Then, the film is immersed for 120–180 s in a solution consisting of 15 parts by weight of sodium dichromate, 250 parts by weight of concentrated acid, and 25 parts by weight of distilled water, heated to 70 °C. After treatment, the polymer films are rinsed with distilled water and dried. During chemical modification, new functional groups form on the film surface, enabling more active interactions with other chemical structures, such as adhesives. A similar experiment was conducted to compare the changes in the PE structure.

Protrusion-like structures formed across the entire film surface. The morphological structures of chemical and plasma modifications exhibit distinct features, as evidenced by 2D and 3D AFM images of the PE film surface (

Figure 11).

AFM studies of the surface morphologies of polymer films at several points revealed that the untreated samples had uniform surfaces with a low roughness of 29 nm for PE (

Figure 11). After a 10 s modification, roughness

Rmax increased from 29 nm to 120 nm due to the enlargement of structural formations (

Table 4). A 15 s modification decreased roughness without reducing the size of structural formations, indicating thermal smoothing of the PE film surface.

The crystalline supramolecular structure is virtually invisible in the relief of the untreated samples (

Figure 11a,c). After a 10 s modification, the surface is covered with a system of rounded, slightly elongated hillocks up to 120 nm high and 0.8–2 µm in diameter. These are the protruding edges of the lamellae and small spherulites observed on SEM images (

Figure 9). Between the hillocks are relatively smooth amorphous regions, creating an alternation of hard crystalline islands and soft depressions. This relief promotes mechanical adhesion, allowing bitumen mastic to flow into the depressions and around the protrusions, creating numerous micro-adhesions. The maximum concentration of polar groups ensures the highest adhesive bond strength and the film’s cohesive failure (51 N/cm to the steel substrate). With a 15 s modification, the hillocks become more gradual, the relief height decreases, and individual protrusions are tightened and smoothed. This is a direct consequence of localized thermal exposure and more intense etching of the amorphous layers. After 15 s of exposure to the GAP, the electrode temperature approaches 70 °C, and the surface layer begins to melt. The crystallites become larger, as shown on the SEM images in

Figure 10, but their peaks are partially smoothed. As a result, the mechanical interlocking area decreases, although chemical functionalization remains high. Further GAP modification time resulted in loss of optimal nano- and microrelief and decreased adhesion, despite ongoing oxidation.

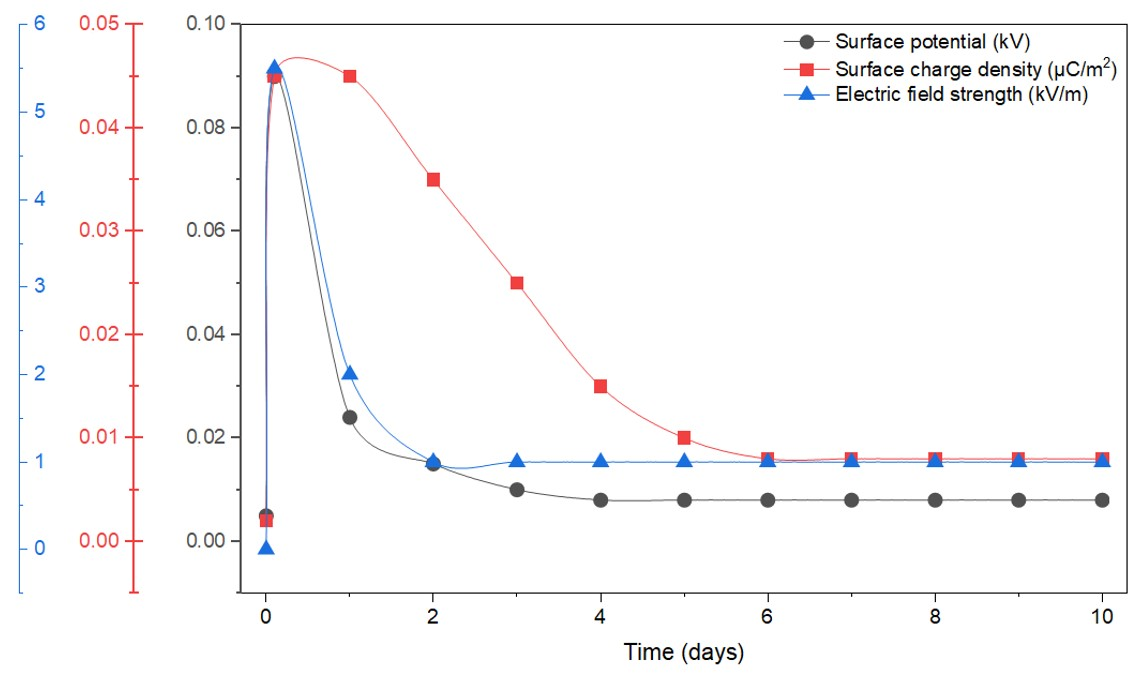

3.6. Kinetics of the Changes in the Electret Properties of Polymer Films Modified in GAP

Plasma modification reorients polar groups, increasing the material’s overall polarity and thereby enhancing intermolecular interactions. Sieve and Maxwell–Wagner polarization also contribute specifically to the polarization of polymers [

60]. This principle underpins techniques used to boost electrostatic adhesion. It is known that energy traps responsible for polarization effects occur at phase boundaries between amorphous and crystalline regions, due to differences in their electrical conductivity. Electret properties were measured using the periodic screening method with an IPEP-1 device. The results for both the untreated and modified samples are shown in

Table 5.

The increase in adhesion work can be attributed to improvements in the electret properties of PE films relative to their initial values. However, over time, due to surface charge relaxation, adsorption, and the transfer of functional groups from the surface into the bulk of the polymer films—known as segmental mobility of macromolecules—a decrease in electret properties occurs.

When polymer films modified in GAP are stored in air, signs of the described “aging effect” are observed. The aging process occurs in all polymeric materials, and changes in their properties—including increased brittleness—are especially characteristic of films and materials with a highly developed surface area. The aging of polymeric materials results from changes in their structure or composition: a gradual increase in the polymerization coefficient; an increase in the size of crystalline formations; continued chain cross-linking and the formation of spatial networks; oxidation and other chemical interactions with the environment.

Despite these processes, the electret properties remained higher than the initial values after a week. The presence of impurities and stabilizing soot particles had a positive effect on the electret properties, enabling charge retention for 10 days (

Figure 12). Three regions can be distinguished on the curves: growth, decline, and stabilization. The decline and subsequent stabilization process occur within the first 24 h (

Ve = 0.004 kV,

σeff = 0.009 μC/m

2, and

E = 1.1 kV/m). This is because during modification in a gliding arc, charge carriers are injected into the material, where energy traps capture them at various levels. According to physicochemical analysis, these traps include impurities, structural anomalies, and the interface between the crystalline and amorphous phases. The decline in surface potential is due to the release of charge carriers from shallow surface energy traps. After this, the magnitude of the surface potential is determined by the number of injected charge carriers trapped in deeper traps.

Ananyev et al. [

61] and Nguyen [

24] reported that, as analyzed by secondary ion mass spectrometry, the surface of modified films showed an “aging effect” attributed to thermodynamic relaxation and reorientation of polar groups from the surface into the polymer’s interior. The 200-μm-thick polyethylene terephthalate (PET) films were modified with a corona discharge, resulting in electret properties of

Ve = 0.049 kV,

σeff = 0.015 μC/m

2, and

E = 5.8 kV/m. It was reported that the retention of electret properties lasted for 14 days after corona discharge modification.

GAP modification of PE films is technically feasible and provides a stable effect over time. The results of the electret property study supported the understanding of the electrostatic component of adhesion and complemented the research on the supramolecular structure.

3.7. Adhesion Properties of the PE Film to the Steel Substrate

During the operation of a main pipeline buried underground, the pipe surface is exposed to various factors, including longitudinal and transverse deformation forces, thermal effects across different temperature ranges and chemical processes. These factors often work together, not only adding up but also strengthening each other [

62]. Understanding the mechanical properties of waterproofing materials at sub-zero temperatures helps predict their behavior in cold regions such as Siberia and the Far East of the Russian Federation. To study this, a flexibility test on a beam (flexural or bend test) was conducted at −20 °C. According to State standard GOST 2678-94 [

63], the flexibility of a beam made of rolled waterproofing materials should be at least 15°. The flexibility of a sample comprising a waterproofing material based on GAP-modified PE film, combined with “Transcor-Gaz” (JSC “Delan”, Moscow, Russia) bitumen mastic, was measured at 20°. This is attributed to the high content of polymer and rubber modifiers in the bitumen mastic of the beam sample [

64]. It is crucial to conduct re-insulation work at sub-zero temperatures in accordance with all installation rules, with the metal surface temperature exceeding 15 °C [

51,

65].

Water resistance testing of modified PE films under a pressure of 0.1 ± 0.01 MPa for 2 ± 0.1 h showed that no water traces were observed on the surface of three samples, confirming the feasibility of producing waterproofing materials based on modified PE films (

Figure 13).

Another cause of failure of rolled waterproofing materials is the degradation of the adhesive joint due to electrochemical processes at the lap joint between the turns of the waterproofing coating, leading to destruction and a reduction in the overall service life of the pipeline. In this regard, the adhesive properties of the polymer film—the base of the waterproofing material—are decisive and influence the coating’s durability [

66]. When conducting adhesion tests on protective coatings in a film–mastic–film system for PE, bonded with “Transcor-Gaz” bitumen mastic, lap-joint strength is determined (

Figure 14). It is crucial that the bonded samples and the adhesive form the most complete contact possible.

The maximum shear load for PE film samples with mastication was achieved with a 10 s GAP modification, where the shear strength increased from 57–58 N to 64–65 N, and the peel adhesion force enhanced from 28–29 to 32 N/cm before and after GAP modification (

Table 6). A longer GAP modification time reduces the shear load. This effect is associated with plasma etching of the surface, as observed in IR spectroscopy studies. The PE films’ surface becomes smoother after longer GAP modification and the relative surface roughness decreases, which reduces adhesion performance according to mechanical theory.

Adhesion of the PE film to primed steel in the PE–mastic–steel system was determined to assess the strength of interaction between the waterproofing material and the main pipeline surface (

Table 7).

The failure mechanism in the PE–mastic–steel system depends on the treatment (

Figure 15). The PE film peeled from the bitumen substrate was observed in the system without GAP modification and after a longer GAP treatment of 30 s (

Figure 15b). After a 10 s GAP modification, cohesive failure of the PE film was established and its adhesion to the primed steel was the highest, reaching 51 N/cm (

Figure 15a). The increase in the film peel force after exposure to GAP is due to the presence of active functional groups on the film surface, which improve its wettability with the bitumen adhesive. When joining samples with the sticky sides together, both cohesive and adhesive failures occur (

Figure 15c).

Waterproofing material based on GAP-modified PE films has higher indicators compared to similar commercial materials, such as “LITKOR” polymer–bitumen tape (MBMP, Moscow, Russia), “LIAM” anti-corrosion tape (PolymerKOR Plant, Samara, Russia) and the “BILAR” combined coating (LLC NPF “ADA”, Ufa, Russia) (

Table 7) [

51].

4. Discussion

It has been established that modification of the surface of polymer films in gliding arc plasma increases the maximum values of the breaking load under shear of the adhesive joint, which is crucial during the operation of the main pipeline in the ground. The shear strength of PE films reaches 65 N, and the adhesion force is 32 N/cm after 10 s of modification in the PE–mastic–PE system. The same GAP treatment parameters resulted in a 20% increase in the adhesion force of the PE films to the steel substrate in the PE–mastic–steel system. A dependence of the GAP modification duration of PE polymer films on the shear strength, adhesion force to mastic and steel was established. The higher properties are associated with the formation of oxygen-containing groups on the film surface, confirmed by IR spectroscopy, SEM and AFM studies.

The mechanism of plasma modification can be explained by plasma-chemical etching processes that remove material from the surfaces of polymer films [

56,

70]. This etching method involves modifying only one side of the polymer film surface, which allows preserving the hydrophobicity of the unmodified side. The bulk of the polymer remains unchanged, retaining the physicochemical and electrophysical properties of the modified material. In studies [

71,

72] on the etching of polymeric materials, it was noted that the erosion rate increases primarily with the reactivity of the plasma-forming gas. Thus, for PE, the etching rates in a helium environment were 7 × 10

2 mg/cm

2 h, in N

2 were 9 × 10

2 mg/cm

2 h, and in O

2 were 42 × 10

2 mg/cm

2 h [

70]. Also, the etching rate of PE associated with the bombardment of the surface with an ion stream is proportional to the specific power of the discharge. As the modified surface area increases, the plasma becomes depleted of active particles, leading to a decrease in the etching rate. Furthermore, the mass change is attributed to plasma-chemical etching of the PE film surfaces (

Figure 16). If the material being modified is located in the plasma beam region, accelerated charged particles break the bonds between carbon and hydrogen molecules, triggering the formation of highly reactive active sites. If the plasma beam is separated from the polymer material being modified, only chemical interaction with plasma atoms and radicals occurs.

During modification of PE films, ionization, excitation, and dissociation of oxygen- and nitrogen-containing molecules into atoms may occur in a small volume of air near the electrode. These atoms then recombine into various groups, such as hydroxyl groups, singlet oxygen (O2), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), ozone (O3), and carboxyl groups. Nitrogen-based substances such as nitric oxide II (NO) and nitric oxide IV (NO2) are also formed and are highly reactive with the surface of the modified PE film. From this, it can be concluded that the etching rate depends on both the gas present in the atmosphere and the polymers’ structure and properties.

A comparative analysis of the obtained data and literature sources indicates convergence of the results [

1,

13,

42,

59,

73]. The current research has potential applications in addressing the peeling of waterproofing from a steel pipeline, thereby increasing its durability. Additionally, the GAP method is an environmentally friendly and resource-efficient alternative to chemical modification.

The gliding arc provides significantly deeper and faster surface activation of PE films: a minimum contact angle of 21.2° and adhesion work of 141.3 mJ/m2 are achieved in just 8–12 s of treatment, whereas industrial corona treaters require 30–90 s to reach an angle below 30–32°, and DBD requires 20–60 s. Even with deliberate over-treatment for up to 60 s, the contact angle rises to only 31–34°, whereas with corona treatment, strong etching and rapid hydrophobic recovery begin after 15–20 s.

The main difference in the costs of plasma and chemical methods of polymer surface modification stems from their different cost structures. Plasma modification methods require high capital investment: the cost of industrial plasma modification systems for polymer materials ranges from 0.5 to 1.5 million rubles. Operating costs are low, as the primary resource—electricity (1–3 kWh)—accounts for 35–50% of them.

There are also technological differences among plasma methods for modifying polymer materials, which affect cost and energy efficiency. Plasma treatment systems for polymers using corona discharge are the most affordable in terms of capital investment. The cost of such equipment ranges from 0.3 to 0.8 million rubles. However, this method provides limited depth and treatment heterogeneity and is not suitable for polymer materials with complex three-dimensional geometries.

The use of low-temperature atmospheric-pressure plasma represents a more versatile, high-tech approach. The cost of these systems ranges from 1 to 1.5 million rubles, but they provide deeper, more uniform, and more reproducible modification of surface properties and effectively process large, complex parts. Chemical methods for modifying polymeric materials are associated with high ongoing costs. The use of reagents and acids results in monthly costs of 0.05 to 0.2 rubles, and hazardous waste disposal costs 500 to 2000 rubles per kilogram. Plasma modification is more energy-efficient because it is performed at room temperature and does not require heating the solutions.

For large-scale production of over 50,000 parts per month, plasma treatment typically becomes cost-effective after 1 to 3 years of operation. Chemical methods are more efficient for small volumes (up to 5000–10,000 parts) or when modification of the entire material is required.

5. Conclusions

The conducted studies showed that using atmospheric-pressure gliding arc plasma to modify polymeric materials, e.g., PE, is effective. Analysis of the results showed that the average adhesion work increased by 79.2 mJ/m2 for PE, almost twice the initial value. It was established that modifying PE films for 30 s or more is impractical, as the increase in adhesion work ceases after that. According to the regression model to maximize adhesion work value (Wadh) greater than 130 mJ/m2 on the PE surface, the optimal modification conditions for PE films were determined to be a 10 s treatment and a deflection angle of 135°.

It was found that the surface roughness Rmax increased by up to 4.1 times after 10 s GAP modification compared to nontreated PE. A study of the electret properties showed that the observed decline and subsequent stabilization of values occurred within the first 24 h. The increase in adhesion work is attributed to improvements in the electret properties of PE films and the complex morphology of PE films after GAP modification.

Studies of the chemical composition of PE film surfaces showed that plasma modification leads to etching of the polymer surface, followed by oxidation under UV radiation and plasma-ion bombardment. The results of IR spectroscopy studies indicated oxidation of the film surface, an increase in the concentration of surface polar groups (-COOH, OH, C=O), and the formation of double bonds (C=C), which led to improved adhesive properties. These results demonstrate that modification of the polymer waterproofing film results in cross-linking of macromolecular chains, thereby increasing its mechanical strength. Mechanical tests indicated improved performance of the GAP-modified PE films compared with untreated PE films in the PE–mastic–PE and PE–mastic–steel systems. The operation of a waterproofing coating is a complex physicochemical process that occurs through various mechanisms and depends on environmental conditions. Determining the durability of a waterproofing material is part of a comprehensive approach to service life studies, enabling testing both during operation, without opening the pipeline or using destructive methods, and during the design phase.