Shrimp-Derived Chitosan for the Formulation of Active Films with Mexican Propolis: Physicochemical and Functional Evaluation of the Biomaterial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Propolis: Source and Characterization

2.1.1. Propolis Source

2.1.2. Microbial Strains

2.1.3. Physicochemical, Antioxidant, and Antimicrobial Characterization of Propolis

2.1.4. Brine Shrimp Lethality Test

2.1.5. Hemolysis Assay

2.2. Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan and Chitosan–Propolis Films

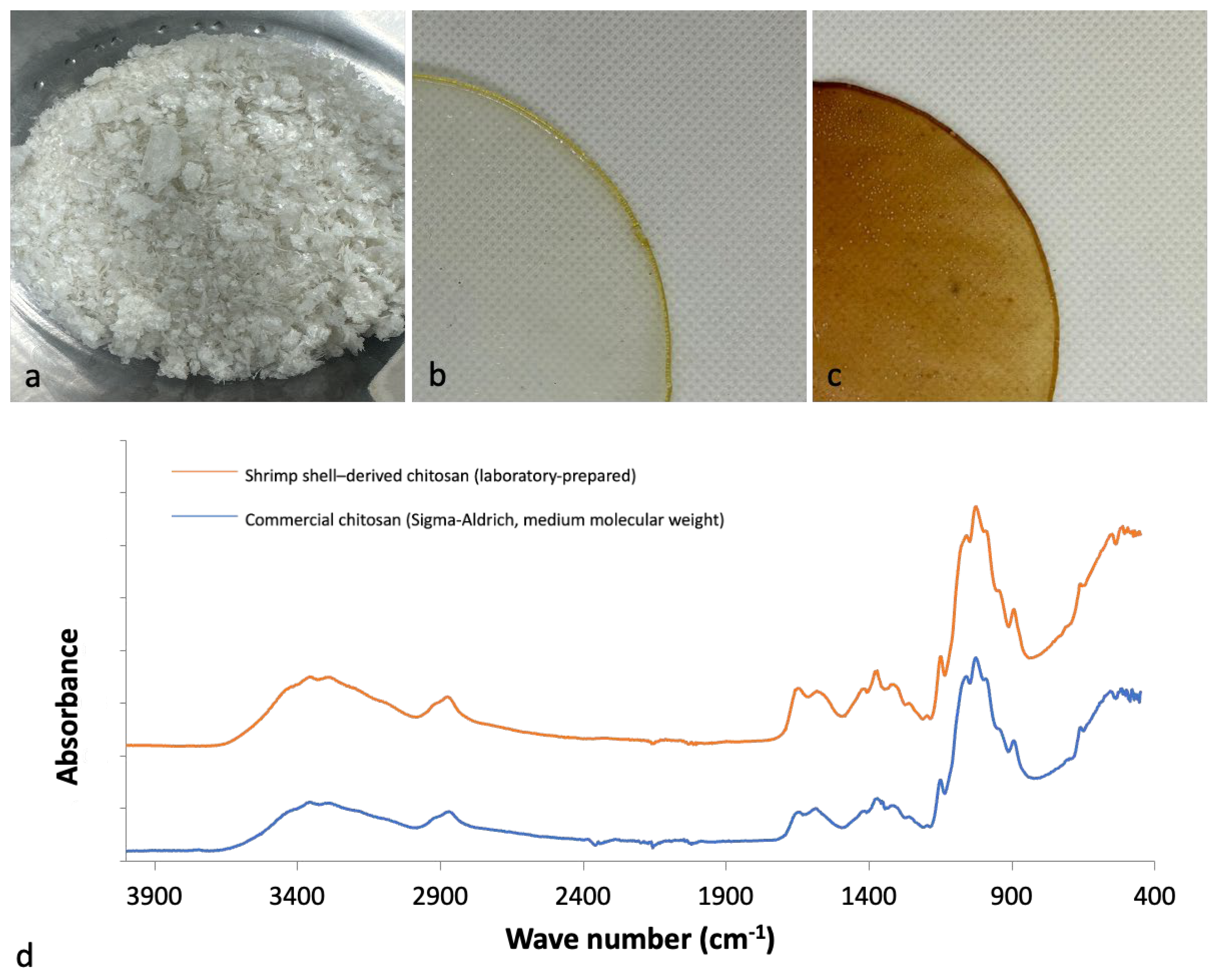

2.2.1. Extraction and Characterization of Chitosan

2.2.2. Preparation of Chitosan and Chitosan–Propolis Films

2.2.3. Antimicrobial Activity of Chitosan and Chitosan–Propolis Films

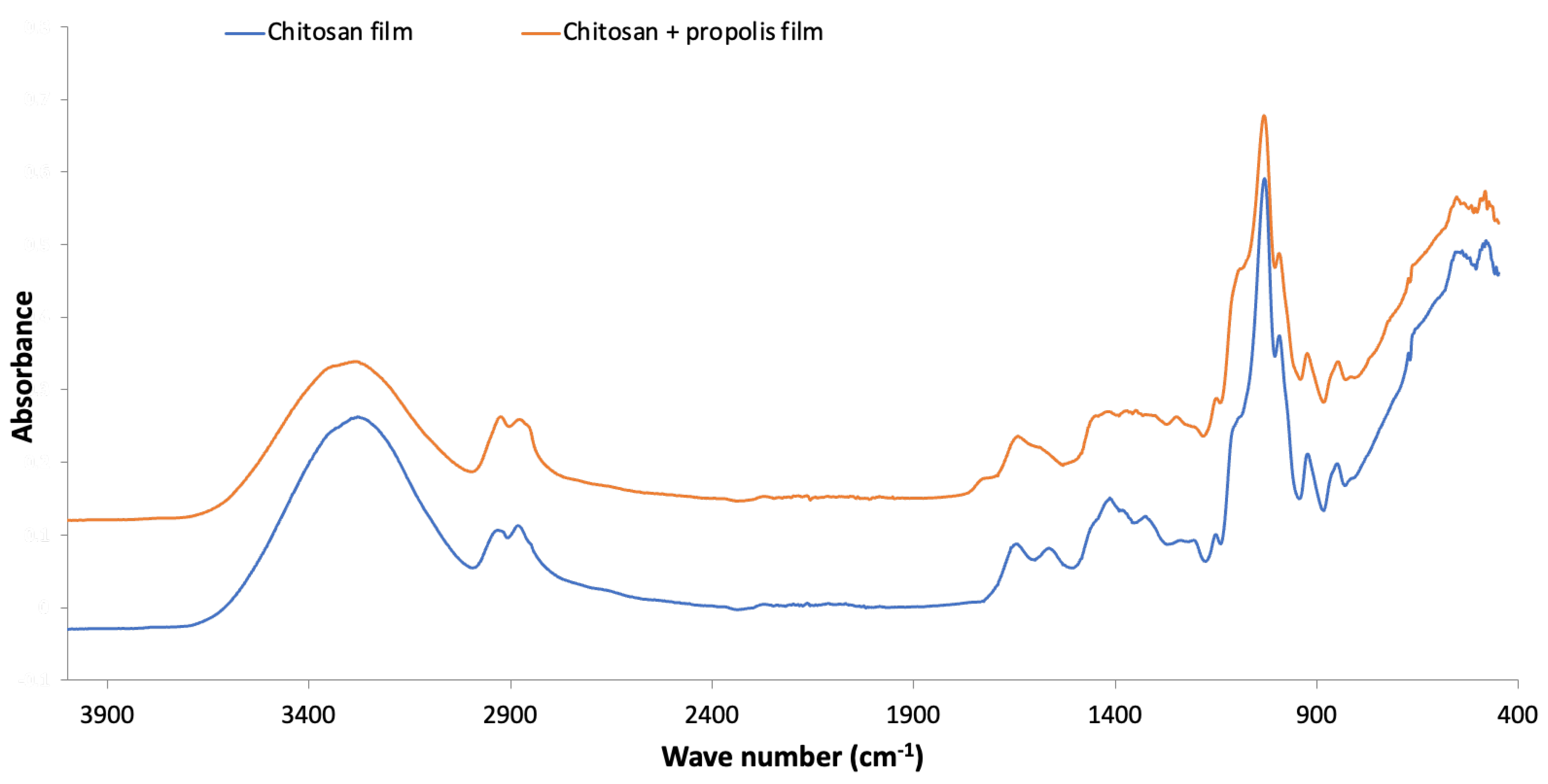

2.2.4. Fourier-Transform Infrared Analysis (FTIR-ATR)

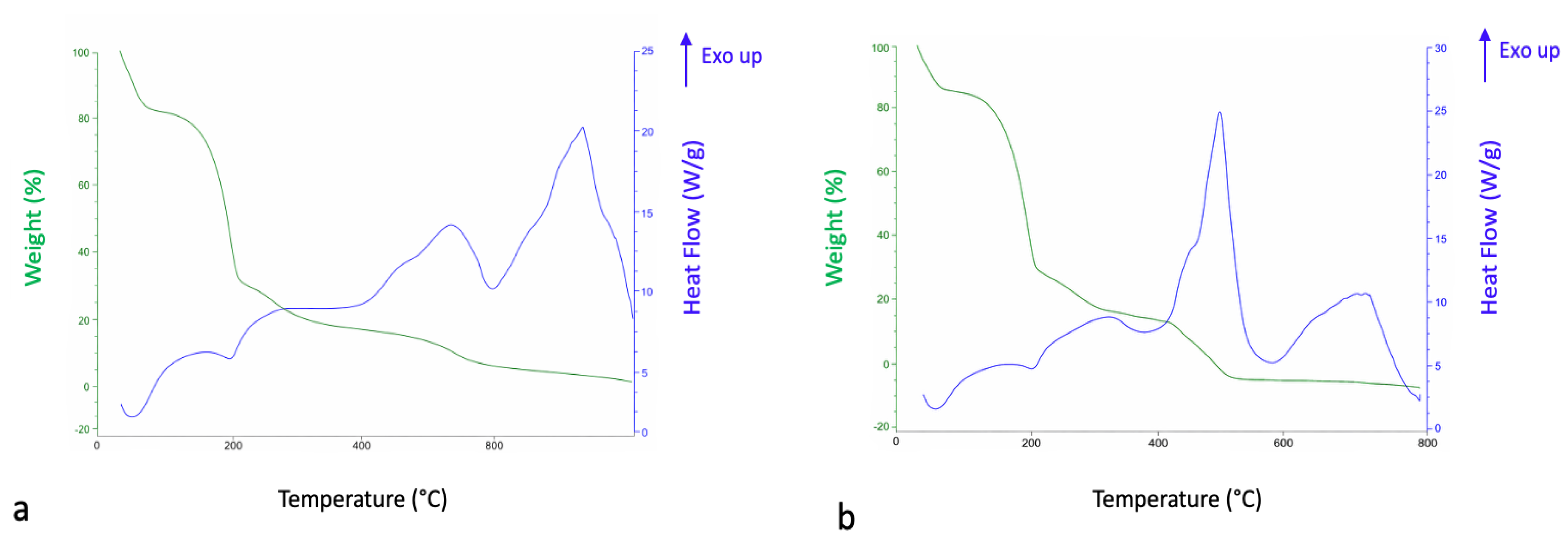

2.2.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

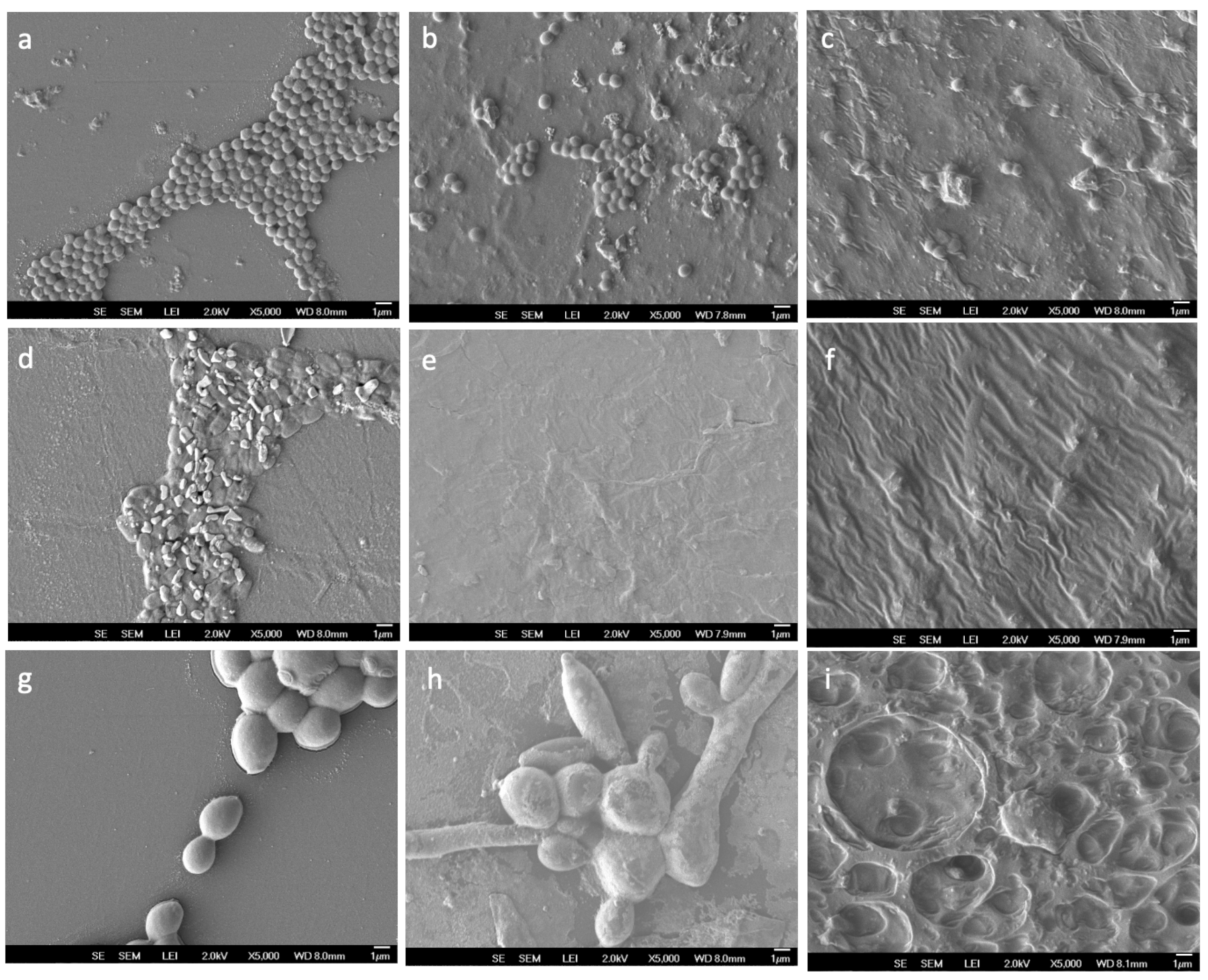

2.2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis of Film–Microorganism Interactions

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATR | Attenuated Total Reflectance |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| CA50 | Concentration required to achieve 50% antioxidant activity |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DPPH• | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| EP | Propolis extract |

| EPSs | Extracellular polymeric substances |

| FTIR | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| LD50 | Median lethal dose |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| ND | Not detected |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

References

- Nanda, D.; Behera, D.; Pattnaik, S.S.; Behera, A.K. Advances in Natural Polymer-Based Hydrogels: Synthesis, Applications, and Future Directions in Biomedical and Environmental Fields. Discov. Polym. 2025, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicea, D.; Nicolae-Maranciuc, A. A Review of Chitosan-Based Materials for Biomedical, Food, and Water Treatment Applications. Materials 2024, 17, 5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amponsah, O.; Nopuo, P.S.A.; Manga, F.A.; Catli, N.B.; Labus, K. Future-Oriented Biomaterials Based on Natural Polymer Resources: Characteristics, Application Innovations, and Development Trends. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saputra, H.A. Andreas Chitosan and Its Biomedical Applications: A Review. Next Mater. 2025, 9, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojczyk, E.; Klama-Baryła, A.; Łabuś, W.; Wilemska-Kucharzewska, K.; Kucharzewski, M. Historical and Modern Research on Propolis and Its Application in Wound Healing and Other Fields of Medicine and Contributions by Polish Studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 262, 113159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarapa, A.; Peter, A.; Buettner, A.; Loos, H.M. Organoleptic and Chemical Properties of Propolis: A Review. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2025, 251, 1331–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, M.; Sip, A.; Mrówczyńska, L.; Broniarczyk, J.; Waśkiewicz, A.; Ratajczak, I. Biological Activity and Chemical Composition of Propolis from Various Regions of Poland. Molecules 2022, 28, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loya-Hernández, L.P.; Arzate-Quintana, C.; Castillo-González, A.R.; Camarillo-Cisneros, J.; Romo-Sáenz, C.I.; Favila-Pérez, M.A.; Quiñonez-Flores, C.M. Propolis-Functionalized Biomaterials for Wound Healing: A Systematic Review with Emphasis on Polysaccharide-Based Platforms. Polysaccharides 2025, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Priyadarshi, R.; Rhim, J.-W. Development of Multifunctional Pullulan/Chitosan-Based Composite Films Reinforced with ZnO Nanoparticles and Propolis for Meat Packaging Applications. Foods 2021, 10, 2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Sharma, A.; Puri, V.; Aggarwal, G.; Maman, P.; Huanbutta, K.; Nagpal, M.; Sangnim, T. Chitosan-Based Polymer Blends for Drug Delivery Systems. Polymers 2023, 15, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevanneshan, Z.; Deypour, M.; Kefayat, A.; Rafienia, M.; Sajkiewicz, P.; Esmaeely Neisiany, R.; Enayati, M.S. Polyurethane-Nanolignin Composite Foam Coated with Propolis as a Platform for Wound Dressing: Synthesis and Characterization. Polymers 2021, 13, 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnevisan, K.; Maleki, H.; Samadian, H.; Doostan, M.; Khorramizadeh, M.R. Antibacterial and Antioxidant Assessment of Cellulose Acetate/Polycaprolactone Nanofibrous Mats Impregnated with Propolis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 140, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskandarinia, A.; Kefayat, A.; Rafienia, M.; Agheb, M.; Navid, S.; Ebrahimpour, K. Cornstarch-Based Wound Dressing Incorporated with Hyaluronic Acid and Propolis: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 216, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodabakhshi, D.; Eskandarinia, A.; Kefayat, A.; Rafienia, M.; Navid, S.; Karbasi, S.; Moshtaghian, J. In Vitro and in Vivo Performance of a Propolis-Coated Polyurethane Wound Dressing with High Porosity and Antibacterial Efficacy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 178, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.M.d.M.C.; da Cruz, N.F.; Lynch, D.G.; da Costa, P.F.; Salgado, C.G.; Silva-Júnior, J.O.C.; Rossi, A.; Ribeiro-Costa, R.M. Hydrogel Containing Propolis: Physical Characterization and Evaluation of Biological Activities for Potential Use in the Treatment of Skin Lesions. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barud, H.d.S.; de Araújo Júnior, A.M.; Saska, S.; Mestieri, L.B.; Campos, J.A.D.B.; de Freitas, R.M.; Ferreira, N.U.; Nascimento, A.P.; Miguel, F.G.; Vaz, M.M.d.O.L.L.; et al. Antimicrobial Brazilian Propolis (EPP-AF) Containing Biocellulose Membranes as Promising Biomaterial for Skin Wound Healing. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 703024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupp, T.; dos Santos, B.D.; Gama, L.A.; Silva, J.R.; Arrais-Silva, W.W.; de Souza, N.C.; Américo, M.F.; de Souza Souto, P.C. Natural Rubber-Propolis Membrane Improves Wound Healing in Second—Degree Burning Model. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 131, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zancanela, D.C.; Funari, C.S.; Herculano, R.D.; Mello, V.M.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Borges, F.A.; de Barros, N.R.; Marcos, C.M.; Almeida, A.M.F.; Guastaldi, A.C. Natural Rubber Latex Membranes Incorporated with Three Different Types of Propolis: Physical-Chemistry and Antimicrobial Behaviours. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2019, 97, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, S.M.; Al-Mofty, S.E.-D.; El-Sayed, E.-S.M.; Omar, A.; Abo Dena, A.S.; El-Sherbiny, I.M. Deacetylated Cellulose Acetate Nanofibrous Dressing Loaded with Chitosan/Propolis Nanoparticles for the Effective Treatment of Burn Wounds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 193, 2029–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, W.A.; Azzazy, H.M. Apitherapeutics and Phage-Loaded Nanofibers As Wound Dressings With Enhanced Wound Healing and Antibacterial Activity. Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 2055–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Yañez, N.; Rodriguez-Canales, M.; Nieto-Yañez, O.; Jimenez-Estrada, M.; Ibarra-Barajas, M.; Canales-Martinez, M.M.; Rodriguez-Monroy, M.A. Hypoglycaemic and Antioxidant Effects of Propolis of Chihuahua in a Model of Experimental Diabetes. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 2018, 4360356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Awale, S.; Tezuka, Y.; Esumi, H.; Kadota, S. Study on the Constituents of Mexican Propolis and Their Cytotoxic Activity against PANC-1 Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurado Castañeda, E.; Ramírez Martínez, C.M.; Carrillo Miranda, L.; Díaz-Barriga, A.S.; Cabrera Contreras, I.A.; Portilla Robertson, J. Eficacia Del Propóleo Mexicano de Apis Millifera En El Tratamiento de La Estomatitis Protésica. Ensayo Clínico Controlado Aleatorizado. Rev. Odontológica Mex. 2022, 25, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOM-003-SAG/GAN-2017; Propolis: Production and Specifications for Its Processing. Official Gazette of the Federation: Mexico City, Mexico, 2017. Available online: https://www.dof.gob.mx/normasOficiales/6794/sagarpa11_C/sagarpa11_C.html (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Rodríguez Pérez, B.; Canales Martínez, M.M.; Penieres Carrillo, J.G.; Cruz Sánchez, T.A. Composición Química, Propiedades Antioxidantes y Actividad Antimicrobiana de Propóleos Mexicanos. Acta Univ. 2020, 30, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Yañez, C.R.; Ruiz-Hurtado, P.A.; Reyes-Reali, J.; Mendoza-Ramos, M.I.; Vargas-Díaz, M.E.; Hernández-Sánchez, K.M.; Pozo-Molina, G.; Méndez-Catalá, C.F.; García-Romo, G.S.; Pedroza-González, A.; et al. Antifungal Activity of Mexican Propolis on Clinical Isolates of Candida Species. Molecules 2022, 27, 5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przybyłek, I.; Karpiński, T.M. Antibacterial Properties of Propolis. Molecules 2019, 24, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankova, V.S.; de Castro, S.L.; Marcucci, M.C. Propolis: Recent Advances in Chemistry and Plant Origin. Apidologie 2000, 31, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, P.P.; Hudz, N.; Yezerska, O.; Horčinová-Sedláčková, V.; Shanaida, M.; Korytniuk, O.; Jasicka-Misiak, I. Chemical Variability and Pharmacological Potential of Propolis as a Source for the Development of New Pharmaceutical Products. Molecules 2022, 27, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridi, R.; Montenegro, G.; Nuñez-Quijada, G.; Giordano, A.; Fernanda Morán-Romero, M.; Jara-Pezoa, I.; Speisky, H.; Atala, E.; López-Alarcón, C. International Regulations of Propolis Quality: Required Assays Do Not Necessarily Reflect Their Polyphenolic-Related In Vitro Activities. J. Food Sci. 2015, 80, C1188–C1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, I.S.R.; Oldoni, T.L.C.; de Alencar, S.M.; Rosalen, P.L.; Ikegaki, M. The Correlation between the Phenolic Composition and Biological Activities of Two Varieties of Brazilian Propolis (G6 and G12). Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 48, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.; Ferrigni, N.; Putnam, J.; Jacobsen, L.; Nichols, D.; McLaughlin, J. Brine Shrimp: A Convenient General Bioassay for Active Plant Constituents. Planta Med. 1982, 45, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna-Vázquez-Gómez, R.; Arellano-García, M.E.; García-Ramos, J.C.; Radilla-Chávez, P.; Salas-Vargas, D.S.; Casillas-Figueroa, F.; Ruiz-Ruiz, B.; Bogdanchikova, N.; Pestryakov, A. Hemolysis of Human Erythrocytes by ArgovitTM AgNPs from Healthy and Diabetic Donors: An In Vitro Study. Materials 2021, 14, 2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanicka, K.; Dobrucka, R.; Woźniak, M.; Sip, A.; Majka, J.; Kozak, W.; Ratajczak, I. The Effect of Chitosan Type on Biological and Physicochemical Properties of Films with Propolis Extract. Polymers 2021, 13, 3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raafat, D.; Sahl, H. Chitosan and Its Antimicrobial Potential—A Critical Literature Survey. Microb. Biotechnol. 2009, 2, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leceta, I.; Guerrero, P.; Ibarburu, I.; Dueñas, M.T.; de la Caba, K. Characterization and Antimicrobial Analysis of Chitosan-Based Films. J. Food Eng. 2013, 116, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, H.C.; Violante, I.M.P.; de Musis, C.R.; Borges, Á.H.; Aranha, A.M.F. In Vitro Effectiveness of Brazilian Brown Propolis against Enterococcus Faecalis. Braz. Oral Res. 2015, 29, S1806-83242015000100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kędzia, B.; Hołderna-Kędzia, E. Pinocembryna–Flawonoidowy Składnik Krajowego Propolisu o Działaniu Opóźniającym Rozwój Choroby Alzheimera. Post. Fitoter. 2017, 18, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamplona-Zomenhan, L.C.; Pamplona, B.C.; da Silva, C.B.; Marcucci, M.C.; Mimica, L.M.J. Evaluation of the in Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of an Ethanol Extract of Brazilian Classified Propolis on Strains of Staphylococcus Aureus. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2011, 42, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helander, I.M.; Nurmiaho-Lassila, E.-L.; Ahvenainen, R.; Rhoades, J.; Roller, S. Chitosan Disrupts the Barrier Properties of the Outer Membrane of Gram-Negative Bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 71, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursi, S.A.; Tükel, Ç. Curli-Containing Enteric Biofilms Inside and Out: Matrix Composition, Immune Recognition, and Disease Implications. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2018, 82, e00028-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Tiwari, M.; Donelli, G.; Tiwari, V. Strategies for Combating Bacterial Biofilms: A Focus on Anti-Biofilm Agents and Their Mechanisms of Action. Virulence 2018, 9, 522–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, P.; Mahanta, D.; Kaul, A.; Ishida, Y.; Terao, K.; Wadhwa, R.; Kaul, S.C. Experimental Evidence for Therapeutic Potentials of Propolis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, J.L.; Veiga, F.F.; Jarros, I.C.; Costa, M.I.; Castilho, P.F.; de Oliveira, K.M.P.; Rosseto, H.C.; Bruschi, M.L.; Svidzinski, T.I.E.; Negri, M. Propolis Extract Has Bioactivity on the Wall and Cell Membrane of Candida Albicans. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 256, 112791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyatem, R.; Auras, R.; Rachtanapun, C.; Rachtanapun, P. Biodegradable Rice Starch/Carboxymethyl Chitosan Films with Added Propolis Extract for Potential Use as Active Food Packaging. Polymers 2018, 10, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutharsan, J.; Boyer, C.A.; Zhao, J. Development and Characterization of Chitosan Edible Film Incorporated with Epoxy-activated Agarose. JSFA Rep. 2022, 2, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowska, K.; Woźniak, M.; Sip, A.; Mrówczyńska, L.; Majka, J.; Kozak, W.; Dobrucka, R.; Ratajczak, I. Characteristics of Chitosan Films with the Bioactive Substances—Caffeine and Propolis. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Phenolic Content (% Gallic Acid Equivalents) | Total Flavonoid Content (% Quercetin Equivalents) | Antioxidant Activity CA50 (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| 8.0 ± 2.6 | 3.91 ± 1.0 | 150.9 ± 35.4 |

| Hemolysis (%) | Brine Shrimp Lethality Test LD50 (µg/mL) | Candida albicans | Escherichia coli | Staphylococcus aureus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition Zone (mm) | ||||

| 3.17 ± 0.8 | 956.3 ± 257.7 | 11.3 ± 0.4 | 13.6 ± 1.8 | 12.2 ± 0.8 |

| Candida albicans | Escherichia coli | Staphylococcus aureus | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition Zone (mm) | |||

| Chitosan film | ND | ND | ND |

| Chitosan–propolis film | 8.9 ± 0.60 | 13.2 ± 0.99 | 11.9 ± 0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Delgado-Lozano, A.; Ledesma-Prado, P.A.; Leyva-Porras, C.; Loya-Hernández, L.P.; Romo-Sáenz, C.I.; Arzate-Quintana, C.; Román-Aguirre, M.; Favila-Pérez, M.A.; Castillo-González, A.R.; Quiñonez-Flores, C.M. Shrimp-Derived Chitosan for the Formulation of Active Films with Mexican Propolis: Physicochemical and Functional Evaluation of the Biomaterial. Coatings 2026, 16, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010124

Delgado-Lozano A, Ledesma-Prado PA, Leyva-Porras C, Loya-Hernández LP, Romo-Sáenz CI, Arzate-Quintana C, Román-Aguirre M, Favila-Pérez MA, Castillo-González AR, Quiñonez-Flores CM. Shrimp-Derived Chitosan for the Formulation of Active Films with Mexican Propolis: Physicochemical and Functional Evaluation of the Biomaterial. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010124

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelgado-Lozano, Alejandra, Pedro Alberto Ledesma-Prado, César Leyva-Porras, Lydia Paulina Loya-Hernández, César Iván Romo-Sáenz, Carlos Arzate-Quintana, Manuel Román-Aguirre, María Alejandra Favila-Pérez, Alva Rocío Castillo-González, and Celia María Quiñonez-Flores. 2026. "Shrimp-Derived Chitosan for the Formulation of Active Films with Mexican Propolis: Physicochemical and Functional Evaluation of the Biomaterial" Coatings 16, no. 1: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010124

APA StyleDelgado-Lozano, A., Ledesma-Prado, P. A., Leyva-Porras, C., Loya-Hernández, L. P., Romo-Sáenz, C. I., Arzate-Quintana, C., Román-Aguirre, M., Favila-Pérez, M. A., Castillo-González, A. R., & Quiñonez-Flores, C. M. (2026). Shrimp-Derived Chitosan for the Formulation of Active Films with Mexican Propolis: Physicochemical and Functional Evaluation of the Biomaterial. Coatings, 16(1), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010124