Abstract

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in late 2019, and the catastrophe faced by the world in 2020, the food industry was one of the most affected industries. On the one hand, the pandemic-induced fear and lockdown in several countries increased the online delivery of food products, resulting in a drastic increase in single-use plastic packaging waste. On the other hand, several reports revealed the spread of the viral infection through food products and packaging. This significantly affected consumer behavior, which directly influenced the market dynamics of the food industry. Still, a complete recovery from this situation seems a while away, and there is a need to focus on a potential solution that can address both of these issues. Several biomaterials that possess antiviral activities, in addition to being natural and biodegradable, are being studied for food packaging applications. However, the research community has been ignorant of this aspect, as the focus has mainly been on antibacterial and antifungal activities for the enhancement of food shelf life. This review aims to cover the different perspectives of antiviral food packaging materials using established technology. It focuses on the basic principles of antiviral activity and its mechanisms. Furthermore, the antiviral activities of several nanomaterials, biopolymers, natural oils and extracts, polyphenolic compounds, etc., are discussed.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease, popularly known as COVID-19, is a highly transmissible viral infection caused by the SARS-CoV-2 viral strain. It was initially identified in December 2019, and the initial infections were presumed to be linked to the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan city of China [1]. The transmission rate of this virus among humans was so severe that it was ultimately declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) before too long in March 2020 [1]. This sudden unforeseen incident caused global turmoil, especially among biotechnologists and virologists, who struggled to decode this puzzle. Zhou et al. carried out the genetic sequencing of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. They compared it with the bat coronavirus and found 96.2% similarity between the genetic organization, suggesting the role of bats in the spread of this pandemic [2]. As the coronavirus research evolved, the United States Center for Disease Control revealed that the first report on the human coronavirus dates back to the 1960s. Several variants have been discovered to date [3,4]. The viruses are capable of causing mild respiratory symptoms in humans and, with genetic evolution over the years, have differentiated into several strains with different properties. SARS-CoV-2, which was the variant responsible for COVID-19, belongs to the same category of coronaviruses to which Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)-CoV and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)-CoV belong [4]. Since the primary transmission route of this category of viruses is the spread of droplets during coughing and sneezing, they are capable of easily infecting a large population.

With the advancement of this pandemic, several countries enforced nationwide lockdowns to control viral transmission. People were forced to stay indoors and work from home, which, along with the total or partial closure of food establishments, made them largely dependent on online ordering to meet their hunger needs [5]. This sudden and unusual shift in the consumer behavior of ordering food online resulted in an exponential increase in packaging-based non-biodegradable municipal solid waste, the highest contributor being single-use plastics. This further worsened the already existing massive problem of municipal waste disposal, resulting in negative environmental consequences [5].

In addition to the negative consequences on the environment, the increased use of packaging material led to negative health repercussions. It was reported that viral droplets > 5 μm in size were too heavy to stay airborne and landed on surfaces and objects [6]. These infected surfaces and objects emerged as the indirect and more prevalent source of cross-contamination, as the viruses were reported to stay active on surfaces depending on the material type [5,7]. Studies reported that coronavirus persisted on plastic for 72 h and cardboard surfaces for 24 h [7]. These materials, which play an important role in the packaging of processed and ready-to-eat food, came under suspicion. The long stability of SARS-CoV-2 on the surfaces of packaging materials created substantial risks and worries regarding the global trade of packaged food, as the virus was capable of surviving on the surface for the whole duration from production to consumption. Meanwhile, China reported the presence of coronavirus strains on animal product packages of Brazilian origin, which provided sufficient evidence that food packaging material may carry viruses, leading to cross-contamination hazards [7]. The European Union also highlighted the possibility of viral transmission via food packages [7].

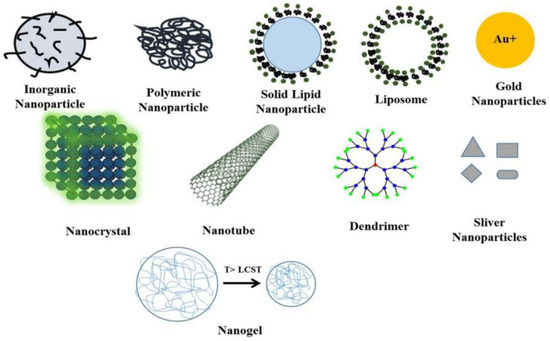

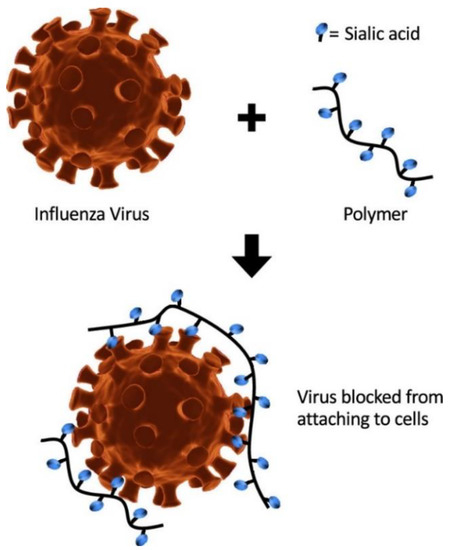

These issues may be addressed by promoting the research on biopolymer composites for food packaging and developing practical applications. In the last decade, much research has been conducted on natural biodegradable polymers for food packaging applications [8,9,10,11]. Moreover, there have been many reports on the natural antibacterial and antifungal additives present in these biopolymer films that could help in extending the shelf life of packaged food products [12,13]. Furthermore, these biopolymer composites have been studied as a standalone packaging material and as surface coatings, either directly on the food surface or as a coated layer on other packaging materials such as paperboard [14]. Nevertheless, to date, the focus has been entirely on the antibacterial and antifungal aspects of these functional biopolymer composite materials. Many of these active components and base biopolymers possess antiviral properties that have long gone unnoticed [15,16,17,18]. Biopolymers (such as chitosan [19] and carrageenan [20]), nanomaterials (such as silver [21]), polyphenolic components (such as lignin [22]), and natural oils and extracts (such as thyme [23], eucalyptus [24], and clove [25]), have been widely reported to possess strong antiviral activities.

This review aims to cover the different perspectives of antiviral food packaging materials using established technology. The prime focus is on the basic principles of antiviral activity and its mechanisms. Furthermore, the antiviral activities of several nanomaterials, biopolymers, natural oils and extracts, polyphenolic compounds, etc., are debated. Finally, the current developments in the research on biodegradable antiviral food packaging materials and coatings are reviewed, and possible future progress in this research area is discussed.

2. Virus Structure and Infection Mechanisms

For the development of antiviral materials, understanding the virus types, their structure, and infection mechanisms is paramount. Viruses are tiny opportunistic intracellular parasites with a structure consisting of an outer protein coat covering nucleic acid (RNA or DNA) in its core. A complete virus particle is called a virion. Viruses require a complex metabolic and biosynthetic machinery of eukaryotic or prokaryotic host cells for propagation and proliferation. Therefore, the virion transports its RNA or DNA genome to host cells for it to be transcribed and translated. This leads to the formation of new virus particles, where a new copy of the genome results from transcription, while their protein capsid is formed due to translation. The viral genome and linked proteins are wrapped in a symmetric protein capsid to form new virions. The nucleic acid-linked protein is called nucleoprotein, and together with the genome, it forms the nucleocapsid. In enveloped viruses, the nucleocapsid is encircled by a lipid bilayer derived from the modified host cell membrane and studded with an outer layer of virus envelope glycoproteins [26].

Viruses are classified based on their nucleic acid content, the shape of their protein capsid, their size, and the surrounding lipoprotein envelope. Their major taxonomic distribution involves two classes based on nucleic acid content: DNA and RNA viruses [27]. The DNA or RNA viruses are further sub-divided based on whether they have double-stranded or single-stranded DNA/RNA. An additional sub-division of the RNA viruses is carried out based on the segmentation of the RNA genome. Single-stranded RNA viruses are further classified into positive-sense viruses (i.e., RNA can be directly translated into proteins) or negative-sense viruses (i.e., RNA requires a polymerase for transcription into mRNA).

Coronaviruses are spherical, enveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA viruses. In clinical practice, the most frequent coronaviruses are OC43, 229E, HKU1, and NL63, which characteristically depict common cold- and flu-related symptoms in immune-competent people. SARS-CoV-2 is the third virus in the coronavirus family that has globally stimulated serious ailments in humans [28] after Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) [29] and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) [30].

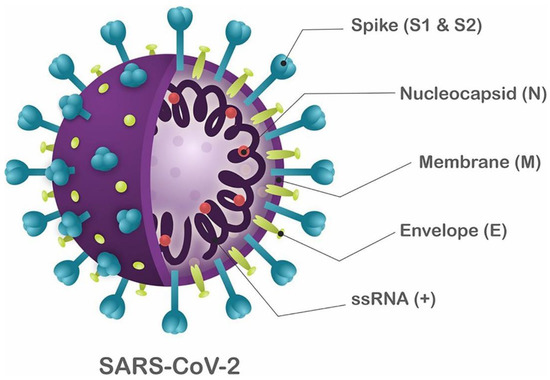

SARS-CoV-2 has a spherical shape with a diameter ranging from 60 nm to 140 nm and distinctive spikes ranging from 9 nm to 12 nm. This gives SARS-CoV-2 virions a look similar to that of the solar corona (Figure 1) [31]. SARS-CoV-2 is assumed to infect new hosts by changing its spike protein and structure through genetic recombination and variation.

Figure 1.

Schematic structure of SARS-CoV-2. The viral structure is primarily formed by structural proteins, such as spike (S), membrane (M), envelope (E), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins. The S, M, and E proteins are embedded in the viral envelope, a lipid bilayer derived from the host cell membrane. The N protein interacts with the viral RNA in the core of the virion. Adapted with permission from ref. [32], published by Frontiers, 2020.

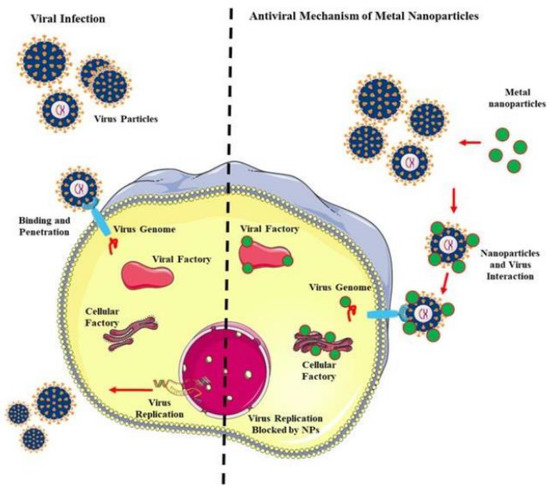

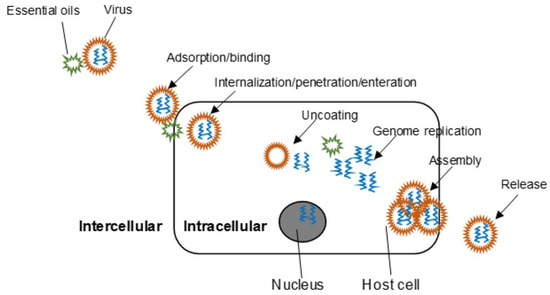

The virus infection cycle commences with the invasion of the host cell by the virion. The virion is adsorbed on the host cell surface and undergoes attachment in this step. After that, it either infiltrates the exterior layer of the host cell to enter the cytoplasm or instills its genetic material into the cell interior while the outer protein capsid and/or envelope relics at the surface of the host cell. A consequent uncoating step occurs inside the host cell when the virion structure infiltrates completely. This step releases genetic material from the virion to the host cell. In both scenarios, the virus’s genetic material cannot initiate protein synthesis until it is released from the virion structure.

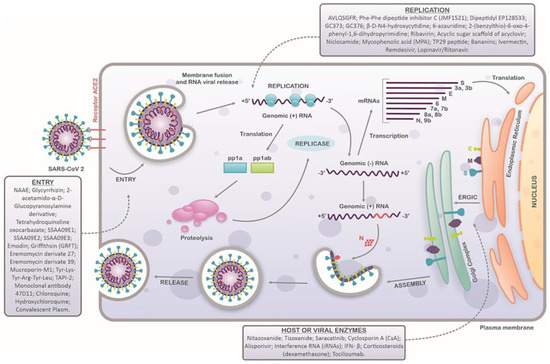

In the case of coronaviruses (SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2), when viral infection occurs and the virion comes in contact with the host cell, the viral surface glycoprotein attaches to the ACE2 receptor on the host cell surface. As this happens, viral endocytosis is triggered, and endosome formation is initiated. The S glycoprotein comprises two subunits, S1 and S2. As endocytosis commences, the S1 subunit undergoes proteolytic cleavage by cellular proteases, exposing the S2 subunit, a fusion peptide responsible for fusing the viral envelope with the endosome membrane. This process ultimately releases the viral capsid, exposing the viral RNA. Following this, the single-stranded, positive-sense RNA of the virus is translated to produce nonstructural proteins that assemble to form a replicase–transcriptase complex (RTC) responsible for the RNA synthesis, replication, and transcription of nine subgenomic RNAs. These subgenomic RNAs are finally translated to generate S, E, and M structural proteins, which are forwarded to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). In this cell organelle, the viral genomes are encapsulated by N proteins and assembled with these structural proteins to form new virions, which are finally transported to the cell surface in vesicles and released in a pathway mediated by exocytosis [32]. The basic infection cycle of a SARS-CoV-2 virion is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of SARS-CoV-2 replication cycle in host cells. SARS-CoV-2 attaches to the host cells by interacting with the ACE2 receptors and spike proteins. After entry, the viral uncoating process releases the viral genome, and the replication stage occurs (translation and transcription). Structural proteins are produced in the intermediate compartment of the endoplasmic reticulum with the Golgi complex and forwarded to assembly, packaging, and virus release. Compounds with antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 are indicated in each step of the virus replication cycle. Adapted with permission from ref. [32], published by Frontiers, 2020.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Since the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 virus-related global pandemic in 2019, the food industry has faced many impediments, especially in food packaging. Since the majority of the packaging material used throughout the world involves the use of non-biodegradable plastics, it has caused two major issues: (a) with the global lockdown and upsurge in food delivery services to meet the hunger needs of people, the utilization of plastic-based packaging increased, which, in turn, led to an increase in non-biodegradable municipal solid waste; (b) there had been reports on the transmission of viral infection due to cross-contamination caused by the packaging material while in use or even after disposal, as the coronavirus actively persists on plastic for long periods of 72 h.

Biopolymer-based food packaging materials are possible alternatives to non-biodegradable packaging and can help solve these issues. Since biopolymers are biodegradable, their contribution to municipal solid waste will be markedly reduced. Moreover, several biopolymers, such as alginate, carrageenan, and chitosan, commonly used in the fabrication of biodegradable food packaging films, have been reported to possess antiviral activity. Packaging materials made from antiviral biopolymers will prevent the persistence of viral particles on their surfaces and, hence, will avert cross-contamination. Furthermore, incorporating sustainable additives into these polymer films can enhance the antiviral potential of these films. Antiviral additives, such as nanomaterials, natural oils, and herbal extracts, will help facilitate the packaging material’s physicochemical properties while contributing to its antiviral efficacy. From a sustainability perspective, biopolymer films incorporated with natural oils and plant extracts could be a completely natural, economic, safer, and eco-friendly option for the fabrication of biopolymer-based antiviral packaging.

Biodegradable polymeric materials incorporated with natural oils and plant extracts have long been studied for potential food packaging applications. Although these materials have been widely studied for their several functionalities, such as antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant properties, there is a scarcity of reports discussing their antiviral food packaging properties. However, independent reports elaboratively discuss the antiviral properties of ionic biopolymers, plant extracts, and essential oils, which can help researchers reach a logical conclusion that many of the biodegradable packaging materials studied to date tend to possess antiviral functionality. However, concrete quantitative and qualitative research is still needed to prove this hypothesis. To ensure food safety and sustainability, exploring the potential of natural antiviral bioactive components in food packaging is essential. Moreover, it is presumed that the demand for biodegradable antiviral food packaging and coatings will increase further in the post-pandemic period, and efforts are required to analyze the practicality of these natural antiviral materials and their potential to be quickly commercialized.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P.; investigation, R.P. and S.D.P.; writing—original draft, R.P., S.D.P., S.R. and T.G.; writing—review and editing, J.-W.R., R.P. and S.S.H.; visualization, R.P. and S.D.P.; funding acquisition, J.-W.R.; supervision, J.-W.R. and S.S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Brain Pool Program funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning through the National Research Foundation of Korea (2019H1D3A1A01070715), and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (2022R1A2B5B02001422).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wu, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-S.; Chan, Y.-J. The Outbreak of COVID-19: An Overview. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2020, 83, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. A Pneumonia Outbreak Associated with a New Coronavirus of Probable Bat Origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kahn, J.S.; McIntosh, K. History and Recent Advances in Coronavirus Discovery. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2005, 24, S223–S227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Shin, W.I.; Pang, Y.X.; Meng, Y.; Lai, J.; You, C.; Zhao, H.; Lester, E.; Wu, T.; Pang, C.H. The First 75 Days of Novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Outbreak: Recent Advances, Prevention, and Treatment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Oliveira, W.Q.; de Azeredo, H.M.C.; Neri-Numa, I.A.; Pastore, G.M. Food Packaging Wastes amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Trends and Challenges. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klompas, M.; Baker, M.A.; Rhee, C. Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: Theoretical Considerations and Available Evidence. JAMA 2020, 324, 441–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jyoti; Bhattacharya, B. Impact of COVID-19 in Food Industries and Potential Innovations in Food Packaging to Combat the Pandemic—A Review. Sci. Agropecu. 2021, 12, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabra, M.J.; López-Rubio, A.; Lagaron, J.M. Biopolymers for Food Packaging Applications. In Smart Polymers And Their Applications; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2014; pp. 476–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grujić, R.; Vujadinović, D.; Savanović, D. Biopolymers as Food Packaging Materials. In Advances In Applications of Industrial Biomaterials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyeye, O.A.; Sadiku, E.R.; Babu Reddy, A.; Ndamase, A.S.; Makgatho, G.; Sellamuthu, P.S.; Perumal, A.B.; Nambiar, R.B.; Fasiku, V.O.; Ibrahim, I.D.; et al. The Use of Biopolymers in Food Packaging. In Green Biopolymers and Their Nanocomposites; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, R.; Sabbah, M.; Di Pierro, P. Biopolymers as Food Packaging Materials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, R.; Roy, S.; Ghosh, T.; Biswas, D.; Rhim, J.-W. Antimicrobial Nanofillers Reinforced Biopolymer Composite Films for Active Food Packaging Applications—A Review. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2021, e00353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, R.; Rhim, J.-W. Chitosan-Based Biodegradable Functional Films for Food Packaging Applications. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 62, 102346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Rhim, J.-W. Antimicrobial Wrapping Paper Coated with a Ternary Blend of Carbohydrates (Alginate, Carboxymethyl Cellulose, Carrageenan) and Grapefruit Seed Extract. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 196, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramaniam, B.; Prateek; Ranjan, S.; Saraf, M.; Kar, P.; Singh, S.P.; Thakur, V.K.; Singh, A.; Gupta, R.K. Antibacterial and Antiviral Functional Materials: Chemistry and Biological Activity toward Tackling COVID-19-like Pandemics. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2020, 4, 8–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randazzo, W.; Fabra, M.J.; Falcó, I.; López-Rubio, A.; Sánchez, G. Polymers and Biopolymers with Antiviral Activity: Potential Applications for Improving Food Safety. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 754–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sha-Tshibey Tshibangu, D.; Liyongo Inkoto, C.; T Tshibangu, D.S.; Matondo, A.; Lengbiye, E.M.; Inkoto, C.L.; Ngoyi, E.M.; Kabengele, C.N.; Bongo, G.N.; Gbolo, B.Z.; et al. Possible Effect of Aromatic Plants and Essential Oils against COVID-19: Review of Their Antiviral Activity. J. Complement. Altern. Med. Res. 2020, 11, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parham, S.; Kharazi, A.Z.; Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R.; Nur, H.; Ismail, A.F.; Sharif, S.; Ramakrishna, S.; Berto, F. Antioxidant, Antimicrobial and Antiviral Properties of Herbal Materials. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amankwaah, C.; Li, J.; Lee, J.; Pascall, M.A. Development of Antiviral and Bacteriostatic Chitosan-Based Food Packaging Material with Grape Seed Extract for Murine Norovirus, Escherichia coli, and Listeria innocua Control. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 6174–6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcó, I.; Randazzo, W.; Sánchez, G.; López-Rubio, A.; Fabra, M.J. On the Use of Carrageenan Matrices for the Development of Antiviral Edible Coatings of Interest in Berries. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 92, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, T.T.N.; Nam, V.N.; Nhan, T.T.; Ngoc, T.T.B.; Minh, L.Q.; Nga, B.T.T.; Phan Le, V.; Quang, D.V. Silver Nanoparticles as Potential Antiviral Agents against African Swine Fever Virus. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 6, 1250g9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, F.; Jiang, B.; Yuan, Y.; Li, M.; Wu, W.; Jin, Y.; Xiao, H. Biological Activities and Emerging Roles of Lignin and Lignin-Based Products—A Review. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 4905–4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo, S.; Jaime, L.; García-Risco, M.R.; Lopez-Hazas, M.; Reglero, G. Supercritical Fluid Extraction as an Alternative Process to Obtain Antiviral Agents from Thyme Species. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 52, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzler, P.; Schön, K.; Reichling, J. Antiviral Activity of Australian Tea Tree Oil and Eucalyptus Oil against Herpes Simplex Virus in Cell Culture. Pharmazie 2001, 56, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vicidomini, C.; Roviello, V.; Roviello, G.N. Molecular Basis of the Therapeutical Potential of Clove (Syzygium aromaticum L.) and Clues to Its Anti-COVID-19 Utility. Molecules 2021, 26, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.A. Gene Cloning and DNA Analysis: An Introduction; Brown, T.A., Ed.; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gelderblom, H.R. Structure and Classification of Viruses. In Medical Microbiology; Baron, S., Ed.; University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston: Galveston, TX, USA, 1996; ISBN 0963117211. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, N.S.; Zheng, B.J.; Li, Y.M.; Poon, L.L.M.; Xie, Z.H.; Chan, K.H.; Li, P.H.; Tan, S.Y.; Chang, Q.; Xie, J.P.; et al. Epidemiology and Cause of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in Guangdong, People’s Republic of China, in February 2003. Lancet 2003, 362, 1353–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zaki, A.M.; Van Boheemen, S.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Isolation of a Novel Coronavirus from a Man with Pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1814–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, C.S.; Tatti, K.M.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Rollin, P.E.; Comer, J.A.; Lee, W.W.; Rota, P.A.; Bankamp, B.; Bellini, W.J.; Zaki, S.R. Ultrastructural Characterization of SARS Coronavirus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.D.A.; Grosche, V.R.; Bergamini, F.R.G.; Sabino-Silva, R.; Jardim, A.C.G. Antivirals Against Coronaviruses: Candidate Drugs for SARS-CoV-2 Treatment? Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazie, A.A.; Albaaji, A.J.; Abed, S.A. A Review on Recent Trends of Antiviral Nanoparticles and Airborne Filters: Special Insight on COVID-19 Virus. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2021, 14, 1811–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, S.; Qasim, M.; Choi, Y.; Do, J.T.; Park, C.; Hong, K.; Kim, J.H.; Song, H. Antiviral Potential of Nanoparticles—Can Nanoparticles Fight Against Coronaviruses? Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh, A.; Kafshdooz, L.; Razban, Z.; Dastranj Tbrizi, A.; Rasoulpour, S.; Khalilov, R.; Kavetskyy, T.; Saghfi, S.; Nasibova, A.N.; Kaamyabi, S.; et al. An Overview Application of Silver Nanoparticles in Inhibition of Herpes Simplex Virus. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2017, 46, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, M.; Xu, T.; Wang, C.; Zhao, M.; Wang, H.; Chen, T.; Zhu, B. The Inhibition of H1N1 Influenza Virus-Induced Apoptosis by Silver Nanoparticles Functionalized with Zanamivir. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.; Yeom, M.; Lee, T.; Kim, H.O.; Na, W.; Kang, A.; Lim, J.W.; Park, G.; Park, C.; Song, D.; et al. Porous Gold Nanoparticles for Attenuating Infectivity of Influenza A Virus. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, M.Y.; Yang, J.A.; Jung, H.S.; Beack, S.; Choi, J.E.; Hur, W.; Koo, H.; Kim, K.; Yoon, S.K.; Hahn, S.K. Hyaluronic Acid-Gold Nanoparticle/Interferon α Complex for Targeted Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus Infection. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 9522–9531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, H.; Fang, L.; Liang, J.; Xiao, S. Glutathione-Stabilized Fluorescent Gold Nanoclusters Vary in Their Influences on the Proliferation of Pseudorabies Virus and Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, R.; Negi, Y.S. Effect of Varying Filler Concentration on Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle Embedded Chitosan Films as Potential Food Packaging Material. J. Polym. Environ. 2017, 25, 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, R.; Kim, S.-M.; Rhim, J.-W. Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Based Multifunctional Film Combined with Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Grape Seed Extract for the Preservation of High-Fat Meat Products. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2021, 29, e00325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, H.; Tavakoli, A.; Moradi, A.; Tabarraei, A.; Bokharaei-Salim, F.; Zahmatkeshan, M.; Farahmand, M.; Javanmard, D.; Kiani, S.J.; Esghaei, M.; et al. Inhibition of H1N1 Influenza Virus Infection by Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Another Emerging Application of Nanomedicine. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, A.; Ataei-Pirkooh, A.; Mm Sadeghi, G.; Bokharaei-Salim, F.; Sahrapour, P.; Kiani, S.J.; Moghoofei, M.; Farahmand, M.; Javanmard, D.; Monavari, S.H. Polyethylene Glycol-Coated Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle: An Efficient Nanoweapon to Fight against Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1. Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 2675–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T. Review on The Role of Zn2+ Ions in Viral Pathogenesis and the Effect of Zn2+ Ions for Host Cell-Virus Growth Inhibition. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. Res. 2019, 2, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tavakoli, A.; Hashemzadeh, M.S. Inhibition of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 by Copper Oxide Nanoparticles. J. Virol. Methods 2020, 275, 113688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurkow, J.M.; Yüzbasi, N.S.; Domagala, K.W.; Pfeiffer, S.; Kata, D.; Graule, T. Nano-Sized Copper (Oxide) on Alumina Granules for Water Filtration: Effect of Copper Oxidation State on Virus Removal Performance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkl, P.; Long, S.; Mcinerney, G.M.; Sotiriou, G.A.; Ahonen, M.; Kogermann, K.; Pestryakov, A.; Mihailescu, I.N.; Papini, E. Antiviral Activity of Silver, Copper Oxide and Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle Coatings against SARS-CoV-2. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sametband, M.; Kalt, I.; Gedanken, A.; Sarid, R. Herpes Simplex Virus Type-1 Attachment Inhibition by Functionalized Graphene Oxide. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.X.; Li, C.M.; Li, Y.F.; Wang, J.; Huang, C.Z. Synergistic Antiviral Effect of Curcumin Functionalized Graphene Oxide against Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 16086–16092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannazzo, D.; Pistone, A.; Ferro, S.; De Luca, L.; Monforte, A.M.; Romeo, R.; Buemi, M.R.; Pannecouque, C. Graphene Quantum Dots Based Systems As HIV Inhibitors. Bioconjug. Chem. 2018, 29, 3084–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, T.; Liang, J.; Dong, N.; Lu, J.; Fu, Y.; Fang, L.; Xiao, S.; Han, H. Glutathione-Capped Ag2S Nanoclusters Inhibit Coronavirus Proliferation through Blockage of Viral RNA Synthesis and Budding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 4369–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Arshad, F.; Sk, M.P. Emergence of Sulfur Quantum Dots: Unfolding Their Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 285, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, R.; Riahi, Z.; Rhim, J.-W.; Han, S.; Lee, S.-G. Sulfur Quantum Dots as Fillers in Gelatin/Agar-Based Functional Food Packaging Films. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 14292–14302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Cai, K.; Han, H.; Fang, L.; Liang, J.; Xiao, S. Probing the Interactions of CdTe Quantum Dots with Pseudorabies Virus. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łoczechin, A.; Séron, K.; Barras, A.; Giovanelli, E.; Belouzard, S.; Chen, Y.T.; Metzler-Nolte, N.; Boukherroub, R.; Dubuisson, J.; Szunerits, S. Functional Carbon Quantum Dots as Medical Countermeasures to Human Coronavirus. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 42964–42974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.J.; Chang, L.; Chu, H.W.; Lin, H.J.; Chang, P.C.; Wang, R.Y.; Unnikrishnan, B.; Mao, J.Y.; Chen, S.Y.; Huang, C.C. High Amplification of the Antiviral Activity of Curcumin through Transformation into Carbon Quantum Dots. Small 2019, 15, 1902641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Gu, J.; Ye, J.; Fang, B.; Wan, S.; Wang, C.; Ashraf, U.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Shao, L.; et al. Benzoxazine Monomer Derived Carbon Dots as a Broad-Spectrum Agent to Block Viral Infectivity. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 542, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza E Silva, J.M.; Hanchuk, T.D.M.; Santos, M.I.; Kobarg, J.; Bajgelman, M.C.; Cardoso, M.B. Viral Inhibition Mechanism Mediated by Surface-Modified Silica Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 16564–16572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaBauve, A.E.; Rinker, T.E.; Noureddine, A.; Serda, R.E.; Howe, J.Y.; Sherman, M.B.; Rasley, A.; Brinker, C.J.; Sasaki, D.Y.; Negrete, O.A. Lipid-Coated Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for the Delivery of the ML336 Antiviral to Inhibit Encephalitic Alphavirus Infection. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bimbo, L.M.; Denisova, O.V.; Mäkilä, E.; Kaasalainen, M.; De Brabander, J.K.; Hirvonen, J.; Salonen, J.; Kakkola, L.; Kainov, D.; Santos, H.A. Inhibition of Influenza A Virus Infection in vitro by Saliphenylhalamide-Loaded Porous Silicon Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 6884–6893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, K.R.; Beloor, J.; Jo, A.; Nguyen, M.N.; Choi, T.G.; Kim, J.H.; Akter, S.; Lee, S.K.; Maeng, C.H.; Baik, H.H.; et al. Liver-Targeted Cyclosporine A-Encapsulated Poly (Lactic-Co-Glycolic) Acid Nanoparticles Inhibit Hepatitis C Virus Replication. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Illescas, B.M.; Rojo, J.; Delgado, R.; Martín, N. Multivalent Glycosylated Nanostructures To Inhibit Ebola Virus Infection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 6018–6025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kandeel, M.; Al-Taher, A.; Park, B.K.; Kwon, H.J.; Al-Nazawi, M. A Pilot Study of the Antiviral Activity of Anionic and Cationic Polyamidoamine Dendrimers against the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 1665–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagno, V.; Andreozzi, P.; D’Alicarnasso, M.; Jacob Silva, P.; Mueller, M.; Galloux, M.; Le Goffic, R.; Jones, S.T.; Vallino, M.; Hodek, J.; et al. Broad-Spectrum Non-Toxic Antiviral Nanoparticles with a Virucidal Inhibition Mechanism. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donskyi, I.; Drüke, M.; Silberreis, K.; Lauster, D.; Ludwig, K.; Kühne, C.; Unger, W.; Böttcher, C.; Herrmann, A.; Dernedde, J.; et al. Interactions of Fullerene-Polyglycerol Sulfates at Viral and Cellular Interfaces. Small 2018, 14, 1800189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liang, J. An Overview of Functional Nanoparticles as Novel Emerging Antiviral Therapeutic Agents. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 112, 110924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, A.R.; Yadav, K.; Khursheed, A.; Rather, M.A. An Updated and Comprehensive Review of the Antiviral Potential of Essential Oils and Their Chemical Constituents with Special Focus on Their Mechanism of Action against Various Influenza and Coronaviruses. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 152, 104620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Yao, L. Antiviral Effects of Plant-Derived Essential Oils and Their Components: An Updated Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, J.; Wang, M.X.; Ang, I.Y.H.; Tan, S.H.X.; Lewis, R.F.; Chen, J.I.P.; Gutierrez, R.A.; Gwee, S.X.W.; Chua, P.E.Y.; Yang, Q.; et al. Potential Rapid Diagnostics, Vaccine and Therapeutics for 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-NCoV): A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Astani, A.; Reichling, J.; Schnitzler, P. Screening for Antiviral Activities of Isolated Compounds from Essential Oils. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 2011, 253643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Salem, M.A.; Ezzat, S.M. The Use of Aromatic Plants and Their Therapeutic Potential as Antiviral Agents: A Hope for Finding Anti-COVID 19 Essential Oils. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2021, 33, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harrasi, A.; Bhatia, S.; Behl, T.; Kaushik, D. Essential Oils in the Treatment of Respiratory Tract Infections. In Role of Essential Oils in the Management of COVID-19; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzoli, S.; Mohamed, M.E.; Tawfeek, N.; Elbaramawi, S.S.; Fikry, E. Agathis Robusta Bark Essential Oil Effectiveness against COVID-19: Chemical Composition, In Silico and In Vitro Approaches. Plants 2022, 11, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badraoui, R.; Saoudi, M.; Hamadou, W.S.; Elkahoui, S.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Alam, J.M.; Jamal, A.; Adnan, M.; Suliemen, A.M.E.; Alreshidi, M.M.; et al. Antiviral Effects of Artemisinin and Its Derivatives against SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease: Computational Evidences and Interactions with ACE2 Allelic Variants. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagno, V.; Sgorbini, B.; Sanna, C.; Cagliero, C.; Ballero, M.; Civra, A.; Donalisio, M.; Bicchi, C.; Lembo, D.; Rubiolo, P. In Vitro Anti-Herpes Simplex Virus-2 Activity of Salvia desoleana Atzei & V. Picci Essential Oil. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pourghanbari, G.; Nili, H.; Moattari, A.; Mohammadi, A.; Iraji, A. Antiviral Activity of the Oseltamivir and Melissa officinalis L. Essential Oil against Avian Influenza A Virus (H9N2). VirusDisease 2016, 27, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roy, S.; Priyadarshi, R.; Ezati, P.; Rhim, J.W. Curcumin and its uses in active and smart food packaging applications-A comprehensive review. Food Chem. 2021, 375, 131885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilling, D.H.; Kitajima, M.; Torrey, J.R.; Bright, K.R. Antiviral Efficacy and Mechanisms of Action of Oregano Essential Oil and Its Primary Component Carvacrol against Murine Norovirus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 116, 1149–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vimalanathan, S.; Hudson, J. Anti-Influenza Virus Activity of Essential Oils and Vapors. Am. J. Essent. Oils Nat. Prod. 2014, 2, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Selvarani, V.; James, H. The Activity of Cedar Leaf Oil Vapor Against Respiratory Viruses: Practical Applications ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feriotto, G.; Marchetti, N.; Costa, V.; Beninati, S.; Tagliati, F.; Mischiati, C. Chemical Composition of Essential Oils from Thymus vulgaris, Cymbopogon citratus, and Rosmarinus officinalis, and Their Effects on the HIV-1 Tat Protein Function. Chem. Biodivers. 2018, 15, e1700436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabra, M.J.; Falcó, I.; Randazzo, W.; Sánchez, G.; López-Rubio, A. Antiviral and Antioxidant Properties of Active Alginate Edible Films Containing Phenolic Extracts. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 81, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianculli, R.H.; Mase, J.D.; Schulz, M.D. Antiviral Polymers: Past Approaches and Future Possibilities. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 9158–9186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C.; Finkelstein, M.S. Interferon-Stimulating and in Vivo Antiviral Effects of Various Synthetic Anionic Polymers. Virology 1968, 35, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Baba, M.; Sato, A.; Pauwels, R.; De Clercq, E.; Shigeta, S. Inhibitory Effect of Dextran Sulfate and Heparin on the Replication of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) in Vitro. Antivir. Res. 1987, 7, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witvrouw, M.; De Clercq, E. Sulfated Polysaccharides Extracted from Sea Algae as Potential Antiviral Drugs. Gen. Pharmacol. Vasc. Syst. 1997, 29, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermelli, C.; Cuoghi, A.; Scuri, M.; Bettua, C.; Neglia, R.G.; Ardizzoni, A.; Blasi, E.; Iannitti, T.; Palmieri, B. In vitro evaluation of antiviral and virucidal activity of a high molecular weight hyaluronic acid. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mallakpour, S.; Azadi, E.; Hussain, C.M. Recent Breakthroughs of Antibacterial and Antiviral Protective Polymeric Materials during COVID-19 Pandemic and after Pandemic: Coating, Packaging, and Textile Applications. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 55, 101480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyadarshi, R.; Kim, H.-J.; Rhim, J.-W. Effect of Sulfur Nanoparticles on Properties of Alginate-Based Films for Active Food Packaging Applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 110, 106155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saedi, S.; Shokri, M.; Priyadarshi, R.; Rhim, J.-W. Carrageenan-Based Antimicrobial Films Integrated with Sulfur-Coated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (Fe3O4@SNP). ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 4913–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Priyadarshi, R.; Rhim, J.-W. Development of Multifunctional Pullulan/Chitosan-Based Composite Films Reinforced with ZnO Nanoparticles and Propolis for Meat Packaging Applications. Foods 2021, 10, 2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.; Packirisamy, G. Nano-Based Antiviral Coatings to Combat Viral Infections. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 2020, 24, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delumeau, L.V.; Asgarimoghaddam, H.; Alkie, T.; Jones, A.J.B.; Lum, S.; Mistry, K.; Aucoin, M.G.; Dewitte-Orr, S.; Musselman, K.P. Effectiveness of Antiviral Metal and Metal Oxide Thin-Film Coatings against Human Coronavirus 229E. APL Mater. 2021, 9, 111114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabra, M.J.; Castro-Mayorga, J.L.; Randazzo, W.; Lagarón, J.M.; López-Rubio, A.; Aznar, R.; Sánchez, G. Efficacy of Cinnamaldehyde Against Enteric Viruses and Its Activity After Incorporation Into Biodegradable Multilayer Systems of Interest in Food Packaging. Food Environ. Virol. 2016, 8, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ordon, M.; Zdanowicz, M.; Nawrotek, P.; Stachurska, X.; Mizielińska, M. Polyethylene Films Containing Plant Extracts in the Polymer Matrix as Antibacterial and Antiviral Materials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordon, M.; Nawrotek, P.; Stachurska, X.; Mizielińska, M. Polyethylene Films Coated with Antibacterial and Antiviral Layers Based on CO2 Extracts of Raspberry Seeds, of Pomegranate Seeds, and of Rosemary. Coatings 2021, 11, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizielińska, M.; Nawrotek, P.; Stachurska, X.; Ordon, M.; Bartkowiak, A. Packaging Covered with Antiviral and Antibacterial Coatings Based on ZnO Nanoparticles Supplemented with Geraniol and Carvacrol. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Mayorga, J.L.; Randazzo, W.; Fabra, M.J.; Lagaron, J.M.; Aznar, R.; Sánchez, G. Antiviral Properties of Silver Nanoparticles against Norovirus Surrogates and Their Efficacy in Coated Polyhydroxyalkanoates Systems. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 79, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghosh, T.; Mondal, K.; Giri, B.S.; Katiyar, V. Silk Nanodisc Based Edible Chitosan Nanocomposite Coating for Fresh Produces: A Candidate with Superior Thermal, Hydrophobic, Optical, Mechanical, and Food Properties. Food Chem. 2021, 360, 130048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, T.; Das, D.; Katiyar, V. Edible Food Packaging: Targeted Biomaterials and Synthesis Strategies. In Nanotechnology in Edible Food Packaging; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 25–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, T.; Katiyar, V. Edible Food Packaging: An Introduction BT—Nanotechnology in Edible Food Packaging: Food Preservation Practices for a Sustainable Future; Katiyar, V., Ghosh, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-981-33-6169-0. [Google Scholar]

- Falcó, I.; Flores-Meraz, P.L.; Randazzo, W.; Sánchez, G.; López-Rubio, A.; Fabra, M.J. Antiviral Activity of Alginate-Oleic Acid Based Coatings Incorporating Green Tea Extract on Strawberries and Raspberries. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 87, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharif, N.; Falcó, I.; Martínez-Abad, A.; Sánchez, G.; López-Rubio, A.; Fabra, M.J. On the Use of Persian Gum for the Development of Antiviral Edible Coatings against Murine Norovirus of Interest in Blueberries. Polymers 2021, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).