Abstract

Lyme disease is the most common vector borne-disease in the United States (US). While the majority of the Lyme disease patients can be cured with 2–4 weeks antibiotic treatment, about 10–20% of patients continue to suffer from persisting symptoms. While the cause of this condition is unclear, persistent infection was proposed as one possibility. It has recently been shown that B. burgdorferi develops dormant persisters in stationary phase cultures that are not killed by the current Lyme antibiotics, and there is interest in identifying novel drug candidates that more effectively kill such forms. We previously identified some highly active essential oils with excellent activity against biofilm and stationary phase B. burgdorferi. Here, we screened another 35 essential oils and found 10 essential oils (Allium sativum L. bulbs, Pimenta officinalis Lindl. berries, Cuminum cyminum L. seeds, Cymbopogon martini var. motia Bruno grass, Commiphora myrrha (T. Nees) Engl. resin, Hedychium spicatum Buch.-Ham. ex Sm. flowers, Amyris balsamifera L. wood, Thymus vulgaris L. leaves, Litsea cubeba (Lour.) Pers. fruits, Eucalyptus citriodora Hook. leaves) and the active component of cinnamon bark cinnamaldehyde (CA) at a low concentration of 0.1% have strong activity against stationary phase B. burgdorferi. At a lower concentration of 0.05%, essential oils of Allium sativum L. bulbs, Pimenta officinalis Lindl. berries, Cymbopogon martini var. motia Bruno grass and CA still exhibited strong activity against the stationary phase B. burgdorferi. CA also showed strong activity against replicating B. burgdorferi, with a MIC of 0.02% (or 0.2 μg/mL). In subculture studies, the top five essential oil hits Allium sativum L. bulbs, Pimenta officinalis Lindl. berries, Commiphora myrrha (T. Nees) Engl. resin, Hedychium spicatum Buch.-Ham. ex Sm. flowers, and Litsea cubeba (Lour.) Pers. fruits completely eradicated all B. burgdorferi stationary phase cells at 0.1%, while Cymbopogon martini var. motia Bruno grass, Eucalyptus citriodora Hook. leaves, Amyris balsamifera L. wood, Cuminum cyminum L. seeds, and Thymus vulgaris L. leaves failed to do so as shown by visible spirochetal growth after 21-day subculture. At concentration of 0.05%, only Allium sativum L. bulbs essential oil and CA sterilized the B. burgdorferi stationary phase culture, as shown by no regrowth during subculture, while Pimenta officinalis Lindl. berries, Commiphora myrrha (T. Nees) Engl. resin, Hedychium spicatum Buch.-Ham. ex Sm. flowers and Litsea cubeba (Lour.) Pers. fruits essential oils all had visible growth during subculture. Future studies are needed to determine if these highly active essential oils could eradicate persistent B. burgdorferi infection in vivo.

1. Introduction

Lyme disease, which is caused by the spirochetal organism Borrelia burgdorferi, is the most common vector borne-disease in the United States (US) with about 300,000 cases a year [1]. While the majority of the Lyme disease patients can be cured with the standard 2–4 weeks antibiotic monotherapy with doxycycline or amoxicillin or cefuroxime [2], about 36% of patients continue to suffer from persisting symptoms of fatigue, joint, or musculoskeletal pain, and neuropsychiatric symptoms, even six months after taking the standard antibiotic therapy [3]. These latter patients suffer from a poorly understood condition, called post-treatment Lyme disease (PTLDS) syndrome. While the cause for PTLDS is unclear and is likely multifactorial, the following factors may be involved: autoimmunity [4], host response to dead debris of Borrelia organism [5], tissue damage caused during the infection, and persistent infection. There have been various anecdotal reports demonstrating persistence of the organism despite standard antibiotic treatment [6,7,8]. For example, culture of B. burgdorferi bacteria from patients despite treatment has been reported as infrequent case reports [9]. In addition, in animal studies with mice, dogs and monkeys, it has been shown that the current Lyme antibiotic treatment with doxycycline, cefuroxime, or ceftriaxone is unable to completely eradicate the Borrelia organism, as detected by xenodiagnosis and PCR [6,7,8,10], but viable organism cannot be cultured in the conventional sense as in other persistent bacterial infections, like tuberculosis after treatment [11,12].

Recently, it has been demonstrated that B. burgdorferi can form various dormant non-growing persisters in stationary phase cultures that are tolerant or not killed by the current antibiotics that are used to treat Lyme disease [13,14,15,16]. Thus, while the current Lyme antibiotics are good at killing the growing B. burgdorferi they have poor activity against the non-growing persisters enriched in stationary phase culture [14,16,17]. Therefore, there is interest to identify drugs that are more active against the B. burgdorferi persisters than the current Lyme antibiotics. We used the stationary phase culture of B. burgdorferi as a persister model and performed high throughput screens and identified a range of drug candidates such as daptomycin, clofazimine, sulfa drugs, daunomycin, etc., which have strong activity against B. burgdorferi persisters. These persister active drugs act differently from the current Lyme antibiotics, as they seem to preferentially target the membrane. We found that the variant persister forms such as round bodies, microcolonies, and biofilms with increasing degree of persistence in vitro, cannot be killed by the current Lyme antibiotics or even persister drugs like daptomycin alone, and that they can only be killed by a combination of drugs that kill persisters and drugs that kill the growing forms [14]. These observations provide a possible explanation in support of persistent infection despite antibiotic treatment in vivo.

Although daptomycin has good anti-persister activity, it is expensive and is an intravenous drug and difficult to administer and adopt in clinical setting and it has limited penetration through blood brain barrier (BBB). Thus, there is interest to identify alternative drug candidates with high anti-persister activity. We recently screened a panel of 34 essential oils and found the top three candidates oregano oil and its active component carvacrol, cinnamon bark, and clove bud as having even better anti-persister activity than daptomycin at 40 μM [18]. To identify more essential oils with strong activity against B. burgdorferi persisters, in this study, we screened an additional 35 different essential oils and found 10 essential oils (garlic, allspice, cumin, palmarosa, myrrh, hydacheim, amyris, thyme white, Litsea cubeba, lemon eucalyptus) and the active component of cinnamon bark cinnamaldehyde as having strong activity in the stationary phase B. burgdorferi persister model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Organism and Culture Conditions

A low passaged strain B. burgdorferi B31 5A19 was kindly provided by Dr. Monica Embers [15]. Firstly, we prepared the B. burgdorferi B31 culture in BSK-H medium (HiMedia Laboratories, Mumbai, India), supplemented with 6% rabbit serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) without antibiotics. After incubation for seven days in microaerophilic incubator (33 °C, 5% CO2), the B. burgdorferi culture went into stationary phase (~107 spirochetes/mL), followed by evaluating potential anti-persister activity of essential oils in a 96-well plate (see below).

2.2. Essential Oils and Drugs

We purchased a panel of essential oils (Plant Guru, Plainfield, NJ, USA) and cinnamaldehyde (CA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The essential oils from Plant Guru company are tested by third party laboratory using GC/MS, and the GC/MS report can be found on their website [19]. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-soluble essential oils were prepared at 10% (v/v) in DMSO as stock solution, which was then added with seven-day old stationary phase cultures at ration of 1:50 to achieve 0.2% of essential oils in the mixture. The 0.2% essential oils were further diluted to the stationary phase culture to get the desired concentration for evaluating anti-borrelia activity. DMSO-insoluble essential oils were directly added to B. burgdorferi cultures, then vortexed to form aqueous suspension, followed by immediate transfer of essential oil aqueous suspension in serial dilutions to desired concentrations and then added to B. burgdorferi cultures. Doxycycline (Dox), cefuroxime (CefU), (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and daptomycin (Dap) (AK Scientific, Union City, CA, USA) were prepared at a concentration of 5 mg/mL in suitable solvents [20,21], then filter-sterilized by 0.2 μm filter and stored at −20 °C as stock solutions.

2.3. Microscopy

Treated B. burgdorferi cell suspensions were checked with BZ-X710 All-in-One fluorescence microscope (KEYENCE, Itasca, IL, USA). The bacterial viability was evaluated by SYBR Green I/PI assay, which was performed by calculating the ratio of green/red fluorescence after dying to determine the ratio of live and dead cells, as described previously [16,22]. The residual cell viability reading was obtained by analyzing three representative images of the same bacterial cell suspension taken by fluorescence microscopy. To quantitatively determine the bacterial viability from microscope images, software of BZ-X Analyzer and Image Pro-Plus were employed to evaluate fluorescence intensity, as we described previously [14].

2.4. Evaluation of Essential Oils for Their Activities Against B. Burgdorferi Stationary Phase Cultures

To evaluate the possible activity of the essential oils against stationary phase B. burgdorferi, 10% DMSO-soluble essential oils or aqueous suspension of DMSO-insoluble essential oils were added to 100 µL of the seven-day old stationary phase B. burgdorferi culture in 96-well plate to obtain the desired concentrations. In the primary screen, each essential oil was assayed with final concentrations of 0.2% and 0.1% (v/v) in 96-well plates. Drugs of daptomycin, doxycycline, and cefuroxime were used as control with final concentration of 40 μM. The active hits were checked further with lower concentrations of 0.1% and 0.05%; all of the tests mentioned above were run in triplicate. All of the plates were sealed and incubated at 33 °C without shaking for seven days, and 5% CO2 were maintained in the incubator.

2.5. Essential Oil and Drug Susceptibility Testing

The live and dead cells after seven-day treatment with essential oils or antibiotics were evaluated using the SYBR Green I/PI assay combined with fluorescence microscopy, as described [16,22]. Briefly, the ratio of live and dead cells was reflected by the ratio of green/red fluorescence, which was calculated through the regression equation and regression curve with least-square fitting analysis.

To determine the Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of cinnamaldehyde on growth of B. burgdorferi, the standard microdilution method was used and the growth inhibition was assessed by microscopy. 10% cinnamaldehyde DMSO stock was added to B. burgdorferi cultures (1 × 104 spirochetes/mL) to get an initial suspension with 0.5% of cinnamaldehyde, and then a series of suspension was prepared by two-fold dilutions, with cinnamaldehyde concentrations ranging from 0.5% (=5 µg/mL) to 0.004% (=0.04 µg/mL). All of the experiments were carried out in triplicate. The B. burgdorferi cultures after treatment in 96-well microplate were incubated at 33 °C for seven days. Cell proliferation was assessed by the SYBR Green I/PI assay combined with BZ-X710 All-in-One fluorescence microscope.

2.6. Subculture Studies to Assess Viability of Essential Oil-Treated B. Burgdorferi Organisms

Essential oils or control drugs were added into 1 mL of seven-day old B. burgdorferi stationary phase culture in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes, incubated for seven days at 33 °C without shaking. Next, cells were centrifuged and cell pellets were washed with fresh BSK-H medium (1 mL) followed by resuspension in 500 μL of the same medium without antibiotics. Then, 50 μL of cell suspension was inoculated into 1 mL of fresh BSK-H medium, incubated at 33 °C for 20 days for subculture. Cell growth was assessed using SYBR Green I/PI assay and fluorescence microscopy, as described above.

3. Results

3.1. Evaluating Activity of Essential Oils Against Stationary Phase B. Burgdorferi

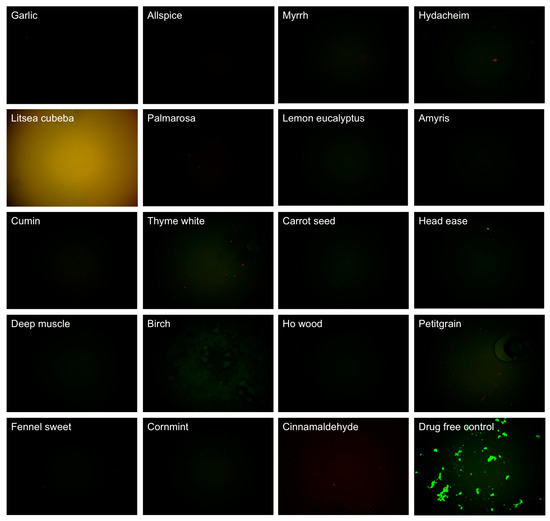

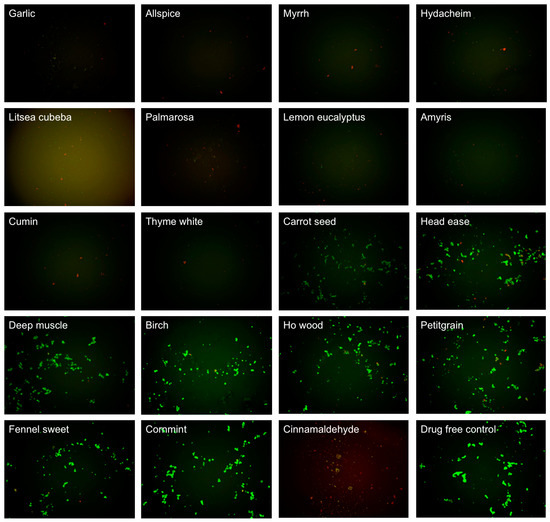

In this study, we explored activity of another panel of 35 new essential oils together with control drugs against a seven-day old B. burgdorferi stationary phase culture in 96-well plates incubated for seven days. Our previous study discovered that cinnamon bark essential oil showed very strong activity against B. burgdorferi culture at stationary phase even at 0.05% concentration [18]. To identify the active components of cinnamon bark essential oil, we also added cinnamaldehyde (CA), the major ingredient of cinnamon bark, in this screen. Table 1 outlines the activity of the 35 essential oils and CA against B. burgdorferi culture at stationary phase. Although the Litsea cubeba essential oil showed too strong autofluorescence to determine its activity at 0.2% concentration, all the other essential oil candidates, except parsley seed, showed significantly stronger activity (p < 0.05) than the doxycycline control (Table 1) at 0.2% concentration with SYBR Green I/PI assay. Among them, 16 essential oils and CA at 0.2% concentration were found to have strong activity against B. burgdorferi culture at stationary phase as compared to the control antibiotics doxycycline, cefuroxime, and daptomycin (Table 1). As previously described [23], we calculated the ratio of residual live cells and dead cells of microscope images using Image Pro-Plus software, which could eliminate the autofluorescence of the background. Using fluorescence microscopy, we confirmed that, at 0.2% concentration, the 16 essential oils and CA could eradicate all live cells with only dead and aggregated cells left as shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. At concentration of 0.1%, 10 essential oils (garlic, allspice, cumin, palmarosa, myrrh, hydacheim, amyris, thyme white, Litsea cubeba, lemon eucalyptus), and CA still exhibited significant activity (p < 0.05) over the current clinically used doxycycline (Table 1; Figure 2). Among them, the most active essential oils were garlic, allspice, cumin, palmarosa, myrrh, and hydacheim because of their remarkable activity even at 0.1%, as shown by totally red (dead) cells with SYBR Green I/PI assay and fluorescence microscope tests (Figure 1). CA also showed very strong activity at 0.1% concentration. Although the plate reader data showed carrot seed and deep muscle essential oils had a significant activity (p < 0.05) compared with the doxycycline control, the microscope result did not confirm it due to high residual viability (60% and 68%, p > 0.05) (Table 1). For the other six essential oils (cornmint, fennel sweet, ho wood, birch, petitgrain, and head ease), which showed strong activity at 0.2% concentration, we did not find them to have higher activity than the doxycycline control at 0.1% concentration (Table 1, Figure 2). In addition, although essential oils of birch and Litsea cubeba have autofluorescence, which showed false high residual viability and interfered with the SYBR Green I/PI plate reader assay, they both exhibited strong activity against the stationary phase B. burgdorferi, as confirmed by SYBR Green I/PI fluorescence microscopy.

Table 1.

Effect of essential oils on a seven-day old stationary phase B. burgdorferi a.

Figure 1.

Effect of 0.2% essential oils on the viability of stationary phase B. burgdorferi. A 7-day old B. burgdorferi stationary phase culture was treated with 0.2% (v/v) essential oils for seven days followed by staining with SYBR Green I/PI viability assay and fluorescence microscopy.

Figure 2.

Effect of 0.1% essential oils on the viability of stationary phase B. burgdorferi. A seven-day old B. burgdorferi stationary phase culture was treated with 0.1% (v/v) essential oils for seven days followed by staining with SYBR Green I/PI viability assay and fluorescence microscopy.

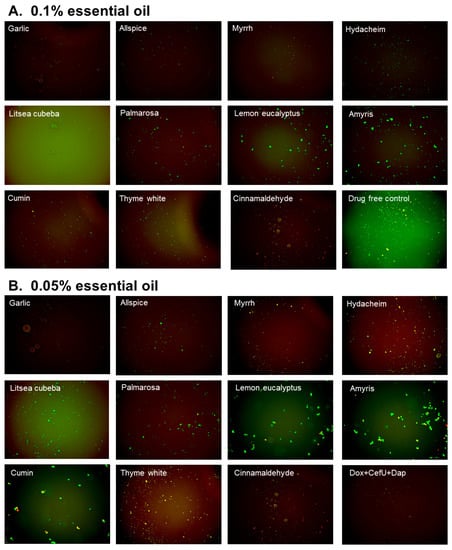

The top 10 essential oils and CA (residual viability lower 60%) were chosen to evaluate their activities and explore their potential to eradicate B. burgdorferi cultures at stationary phase that harbor large numbers of persisters using lower essential oil concentrations (0.1% and 0.05%). We did the confirmation tests with 1 mL stationary phase B. burgdorferi in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes. At 0.1% concentration, the tube tests confirmed the active hits from the previous 96-well plate screen, although the activity of all essential oils decreased slightly in the tube tests when compared to the 96-well plate tests (Table 2, Figure 3). At a very low concentration of 0.05%, we noticed that garlic, allspice, palmarosa, and CA still exhibited strong activity against the stationary phase B. burgdorferi, approved by few residual green aggregated cells shown in Table 2 and Figure 3. Meanwhile, we also found CA showed strong activity against replicating B. burgdorferi, with an MIC of 0.02% (equal to 0.2 μg/mL).

Table 2.

Comparison of top 10 essential oil activities against stationary phase B. burgdorferi with 0.1% and 0.05% (v/v) treatment and subculture a.

Figure 3.

Effect of active essential oils on stationary phase B. burgdorferi. A 1 mL B. burgdorferi stationary phase culture (seven-day old) was treated with 0.1% (A) or 0.05% (B) essential oils (labeled on the image) in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes for 7 days followed by staining with SYBR Green I/PI viability assay and fluorescence microscopy.

3.2. Subculture Studies to Evaluate the Activity of Essential Oils Against Stationary Phase B. burgdorferi

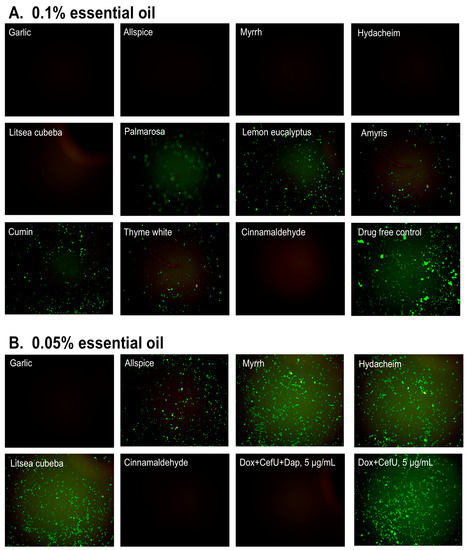

To validate the capability of the essential oils in eradicating B. burgdorferi cells at stationary phase, we performed subculture studies by incubating essential oils treated cells in fresh BSK medium after the removal of the drugs with washing, as previously described [14]. We picked the top 10 active essential oils (garlic, allspice, myrrh, hydacheim, Litsea cubeba, palmarosa, lemon eucalyptus, amyris, cumin, and thyme white) to further confirm whether they could eradicate the stationary phase B. burgdorferi cells at 0.1% or 0.05% concentration by subculture experiments after the essential oil exposure (Table 2). At 0.1% concentration, we did not find any regrowth in samples of the top five hits, including garlic, allspice, myrrh, hydacheim, and Litsea cubeba (Table 2, Figure 4A). However, palmarosa, lemon eucalyptus, amyris, cumin and thyme white could not eradicate B. burgdorferi cells at stationary phase as many spirochetes were still visible after 21 days’ subculture (Figure 4A). The subculture study also confirmed the strong activity of CA by showing no growth of spirochete after treatment with 0.1% CA. At concentration of 0.05%, we did not observe spirochetal regrowth in the garlic essential oil treated samples that were subcultured for 21 days (Figure 4B), which indicates that garlic essential oil could completely kill all B. burgdorferi forms even at 0.05% concentration. On the other hand, the other four active essential oils (allspice, myrrh, hydacheim and Litsea cubeba) at a concentration of 0.05% could not sterilize the B. burgdorferi culture at stationary phase, since spirochetes were visible after 21 days subculture (Figure 4B). Similar to the previous subculture result of cinnamon bark essential oil [18], 0.05% cinnamaldehyde sterilized the B. burgdorferi stationary phase culture as shown by no regrowth after 21 days subculture (Figure 4B), indicating that the active component of cinnamon bark essential oil is attributable to cinnamaldehyde.

Figure 4.

Subculture of B. burgdorferi after treatment with essential oils. A B. burgdorferi stationary phase culture (seven-day old) was treated with the indicated essential oils at 0.1% (A) or 0.05% (B) for seven days followed by washing and resuspension in fresh BSK-H medium and subculture for 21 days. The viability of the subculture was examined by SYBR Green I/PI stain and fluorescence microscopy.

4. Discussion

We recently found that many essential oils have better activity against B. burgdorferi cells at stationary phase than the current clinically used antibiotics for treating Lyme disease [18]. Here, we screened another panel of 35 new essential oils using B. burgdorferi culture at stationary phase as a persister model [16]. Previously, we found that 23 essential oils had strong activity at 1% concentration, but only five of them showed good activity at a lower concentration of 0.25% [18]. To identify the essential oils that have activity against B. burgdorferi persisters at low concentrations, we performed the screen at 0.2% and 0.1% concentrations in this study. Some essential oils, such as Litsea cubeba oil, showed high autofluorescence after SYBR Green I/PI stain, which significantly interfered with the SYBR Green I/PI assay (Table 1, Figure 1). However, using lower concentration (0.1%) and fluorescence microscopy, we were able to verify the results from the SYBR Green I/PI assay and eliminate the problem of autofluorescence with some essential oils. Another limitation of the SYBR Green/PI assay is that not all cells turning red are dead, and further subculture studies are needed to verify whether the PI- stained red cells are indeed dead after drug exposure. In this study, we identified 18 essential oils (at 0.2% concentration) that are more active than 40 μM daptomycin (a persister drug control that could eradicate B. burgdorferi stationary phase cells), from which 10 essential oils stand out as having a remarkable activity even at 0.1% concentration (Table 1). Among them, garlic essential oil exhibited the best activity as shown by the lowest residual viability of B. burgdorferi at 0.1%. In the subsequent comparison studies, the garlic essential oil highlighted itself as showing a sterilizing activity even at a lower concentration of 0.05%, because no Borrelia cells grew up in the subculture study (Table 2). Garlic as a common spice has been used throughout history as an antimicrobial, and a variety of garlic supplements have been commercialized as tablets and capsules. The antibacterial activity of garlic was described by ancient Chinese, and in more recent times, by Louis Pasteur in 1858. Although allicin, an antibacterial compound from garlic, is shown to have antibacterial activity against multiple bacterial species [24,25], it has not been well studied on B. burgdorferi, especially the non-growing stationary phase organism, despite its anecdotal clinical use by some patients with Lyme disease (http://www.natural-homeremedies.com/blog/best-home-remedies-for-lyme-disease/; http://lymebook.com/blog/supplements/garlic-allimax-allimed-alli-c-allicin/). In this study, garlic essential oil was identified as the most potent candidate having activity against stationary phase B. burgdorferi, and its activity is equivalent to that of oregano and cinnamon bark essential oils, the two most active essential oils against B. burgdorferi we identified in our previous study [18].

Additionally, we found four other essential oils, allspice, myrrh, hydacheim, and Litsea cubeba that showed excellent activity against B. burgdorferi at the stationary phase, though the extracts or essential oils of these four plants were reported to possess antibacterial activity on other bacteria. Allspice is a commonly used flavoring agent in food processing and is known to have antibacterial activities on many organisms [26]. Myrrh as a traditional medicine has been used since ancient times. In modern times, myrrh is used as an antiseptic in topical and toothpaste [27]. It has been shown that some sesquiterpene components of myrrh, including furanodien-6-one, methoxyfuranoguai-9-en-8-one possess in vitro bactericidal, and fungicidal activity against multiple pathogenic bacteria, including E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and C. albicans [28], but these two most active compounds were not detected in our samples [19] (Table 3). Hydacheim essential oil is extracted from the flower of Hedychium spicatum plant which is commonly known as the ginger lily plant. The methanol extract of H. spicatum is reported to have antimicrobial activity against many bacteria, including Shigella boydii, E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumoniae [29]. Litsea cubeba is also used in traditional Chinese medicine for a long time. Its essential oils from stem, alabastrum, leaf, flower, root, fruit parts are also reported to exhibit antibacterial activity on B. subtilis, E. coli, E. faecalis, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and M. albicans [30]. Based on these studies and application of allspice, myrrh, hydacheim, and Litsea cubeba, it would be of interest to develop effective regimens to fight against Lyme disease in the future.

Table 3.

The top five major compositions of the three most active essential oils.

Although the active essential oils we identified have strong activity against stationary phase cells of B. burgdorferi in vitro, their activity in vivo is unknown at this time. In future studies, we will use GC-Mass Spectrometry to identify the active ingredients of the active essential oils and confirm their activity against growing and non-growing B. burgdorferi. Once we identify the active components of active essential oils drug combination studies can be performed to enhance activity against persister bacteria. In addition, we will study the mechanism of action of the active compounds in the near future. The pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of the active compounds in these active essential oils will be assessed and their effective dosage and toxicity will be determined in vivo. In our previous study, we found that the cinnamon bark essential oil showed excellent activity against stationary phase B. burgdorferi [18], here we found CA is an active component of cinnamon bark essential oil. CA could eradicate the stationary phase B. burgdorferi at 0.05% concentration as no regrowth occurred in subculture (Table 2). This indicates that CA possess similar activity against stationary phase B. burgdorferi as carvacrol, which is the one of the most active compounds against non-growing B. burgdorferi we identified from natural products [18]. Furthermore, CA is observed to be very active against growing B. burgdorferi cells with an MIC of 0.2 µg/mL. The antibacterial activity of CA was also reported on some other bacteria. The mechanism of the antibacterial activity of CA has been studied on different microorganisms, which suggests that its antibacterial action is mainly through interaction with the cell membrane [31]. CA as a common favoring agent in food processing is also used as food preservative to protect animal feeds and human food from pathogenic bacteria [31]. CA is considered as a safe compound for mammals, as the median lethal dose LD50 of CA is 1850 ± 37 mg/kg by oral administration in the acute toxicity study with oral administration rat model [32]. These findings suggest that CA could be a good drug candidate for further evaluation against B. burgdorferi in future studies. We also want to point out that the safety of using essential oils and their components needs more thorough research; for example, the intravenous toxicity of carvacrol is considerably higher than oral toxicity [33]. Thus, appropriate animal studies are necessary to confirm the safety and activity of CA and other active essential oils in animal models before human studies.

This study used B. burgdorferi stationary phase cultures enriched in persisters as a persister model for essential oil screens. The reason we used this model is that studies with tuberculosis persister drug pyrazinamide (PZA), which is more active against stationary phase cells and persisters than against log phase growing cells and shortens the therapy [34,35], suggest that drugs active against stationary phase cells/persisters will be more effective at curing persistent infections than drugs active against growing cultures. This has been shown in the case of colistin as a persister drug for E. coli when being used together with quinolone or nitrofuran could more effectively eradicate urinary tract infection in mice [36]. Future studies are needed to determine if the essential oils active against non-growing stationary phase B. burgdorferi cultures enriched in persisters are more effective in eradicating persistent B. burgdorferi infections in animal models than the current Lyme antibiotics which are mainly active against growing Borrelia.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we identified some additional essential oils that have strong activity against stationary-phase cells of B. burgdorferi. The most active essential oils include garlic, allspice, myrrh, hydacheim, and Litsea cubeba. Among them, garlic oil could completely eradicate stationary phase B. burgdorferi with no regrowth at 0.05%, and the others could reach the same activity at 0.1%. Additionally, cinnamaldehyde is identified to be an active ingredient of cinnamon bark oil with very strong activity against B. burgdorferi stationary phase cells. Future studies will be carried out to identify the active components in the candidate essential oils, and to determine their in vitro activity alone or in combination with other active essential oils or antibiotics against B. burgdorferi sensu lato strains, including B. burgdorferi, B. garinii and B. afzelii, and assess their safety and efficacy against B. burgdorferi in animal models before human trials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and J.M.; Methodology, J.F., W.S., G.M.T. and C.J.M.; Validation, J.F., W.S., G.M.T. and C.J.M.; Formal Analysis, J.F. and W.S.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, J.F. and Y.Z.; Writing-Review & Editing, Y.Z., J.M.; Supervision, Y.Z.; Funding Acquisition, Y.Z.

Funding

This research was funded in part by Global Lyme Alliance, LivLyme Foundation, NatCapLyme, and the Einstein-Sim Family Charitable Fund.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support by Global Lyme Alliance, LivLyme Foundation, NatCapLyme, and the Einstein-Sim Family Charitable Fund.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- CDC. Lyme Disease. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/lyme/ (accessed on 7 March 2018).

- Wormser, G.P.; Dattwyler, R.J.; Shapiro, E.D.; Halperin, J.J.; Steere, A.C.; Klempner, M.S.; Krause, P.J.; Bakken, J.S.; Strle, F.; Stanek, G.; et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 43, 1089–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aucott, J.N.; Rebman, A.W.; Crowder, L.A.; Kortte, K.B. Post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome symptomatology and the impact on life functioning: Is there something there? Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steere, A.C.; Gross, D.; Meyer, A.L.; Huber, B.T. Autoimmune mechanisms in antibiotic treatment-resistant Lyme arthritis. J. Autoimmun. 2001, 16, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bockenstedt, L.K.; Gonzalez, D.G.; Haberman, A.M.; Belperron, A.A. Spirochete antigens persist near cartilage after murine Lyme borreliosis therapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 2652–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodzic, E.; Imai, D.; Feng, S.; Barthold, S.W. Resurgence of Persisting Non-Cultivable Borrelia burgdorferi following Antibiotic Treatment in Mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Embers, M.E.; Barthold, S.W.; Borda, J.T.; Bowers, L.; Doyle, L.; Hodzic, E.; Jacobs, M.B.; Hasenkampf, N.R.; Martin, D.S.; Narasimhan, S.; et al. Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi in rhesus macaques following antibiotic treatment of disseminated infection. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodzic, E.; Feng, S.; Holden, K.; Freet, K.J.; Barthold, S.W. Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi following antibiotic treatment in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 1728–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, A.; Telford, S.R., 3rd; Turk, S.P.; Chung, E.; Williams, C.; Dardick, K.; Krause, P.J.; Brandeburg, C.; Crowder, C.D.; Carolan, H.E.; et al. Xenodiagnosis to detect Borrelia burgdorferi infection: A first-in-human study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straubinger, R.K.; Summers, B.A.; Chang, Y.F.; Appel, M.J. Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi in experimentally infected dogs after antibiotic treatment. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997, 35, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. Persistent and dormant tubercle bacilli and latent tuberculosis. Front. Biosci. 2004, 9, 1136–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yew, W.W.; Barer, M.R. Targeting persisters for tuberculosis control. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 2223–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.; Brown, A.V.; Matluck, N.E.; Hu, L.T.; Lewis, K. Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, forms drug-tolerant persister cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4616–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Auwaerter, P.G.; Zhang, Y. Drug Combinations against Borrelia burgdorferi persisters in vitro: Eradication achieved by using daptomycin, cefoperazone and doxycycline. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caskey, J.R.; Embers, M.E. Persister development by Borrelia burgdorferi populations in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 6288–6295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Wang, T.; Shi, W.; Zhang, S.; Sullivan, D.; Auwaerter, P.G.; Zhang, Y. Identification of novel activity against Borrelia burgdorferi persisters using an FDA approved drug library. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2014, 3, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Zhang, S.; Shi, W.; Zhang, Y. Ceftriaxone pulse dosing fails to eradicate biofilm-like microcolony B. burgdorferi persisters which are sterilized by daptomycin/doxycycline/cefuroxime without pulse dosing. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Zhang, S.; Shi, W.; Zubcevik, N.; Miklossy, J.; Zhang, Y. Selective Essential oils from spice or culinary herbs have high activity against stationary phase and biofilm Borrelia burgdorferi. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GC/MS TESTING. Available online: https://www.theplantguru.com/gc-ms-testing (accessed on 13 September 2018).

- Wikler, M.A.; National Committee for Clinical Laboratory. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Fifteenth Informational Supplement; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2005.

- The United States Pharmacopeial Convention. The United States Pharmacopeia, 24th ed.; The United States Pharmacopeial Convention: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000.

- Feng, J.; Wang, T.; Zhang, S.; Shi, W.; Zhang, Y. An Optimized SYBR Green I/PI Assay for Rapid Viability Assessment and Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing for Borrelia burgdorferi. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Shi, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y. Identification of new compounds with high activity against stationary phase Borrelia burgdorferi from the NCI compound collection. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2015, 4, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, L.D. Garlic: A Review of Its Medicinal Effects and Indicated Active Compounds. In Phytomedicines of Europe; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 176–209. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovska, B.B.; Cekovska, S. Extracts from the history and medical properties of garlic. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelef, L.A.; Naglik, O.A.; Bogen, D.W. Sensitivity of some common food-borne bacteria to the spices sage, rosemary, and allspice. J. Food Sci. 1980, 45, 1042–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisa, E.L.; Carac, G.; Barbu, V.; Robu, S. The synergistic antioxidant effect and antimicrobial efficacity of propolis, myrrh and chlorhexidine as beneficial toothpaste components. Rev. Chim.-Buchar. 2017, 68, 2060–2065. [Google Scholar]

- Dolara, P.; Corte, B.; Ghelardini, C.; Pugliese, A.M.; Cerbai, E.; Menichetti, S.; Lo Nostro, A. Local anaesthetic, antibacterial and antifungal properties of sesquiterpenes from myrrh. Planta Med. 2000, 66, 356–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritu, A.; Avijit, M. Phytochemical screening and antimicrobial activity of rhizomes of hedychium spicatum. Phcog. J. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of essential oils from different parts of Litsea cubeba. Chem. Biodivers. 2010, 7, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, M. Chemistry, antimicrobial mechanisms, and antibiotic activities of cinnamaldehyde against pathogenic bacteria in animal feeds and human foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 10406–10423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subash Babu, P.; Prabuseenivasan, S.; Ignacimuthu, S. Cinnamaldehyde—A potential antidiabetic agent. Phytomedicine 2007, 14, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feketa, V.V.; Marrelli, S.P. Systemic Administration of the TRPV3 Ion Channel Agonist Carvacrol Induces Hypothermia in Conscious Rodents. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, W.; Zhang, W.; Mitchison, D. Mechanisms of Pyrazinamide Action and Resistance. Microbiol. Spectr. 2013, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Permar, S.; Sun, Z. Conditions that may affect the results of susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to pyrazinamide. J. Med. Microbiol. 2002, 51, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, P.; Niu, H.; Shi, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Margolick, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y. Disruption of membrane by colistin kills uropathogenic Escherichia coli persisters and enhances killing of other antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 6867–6871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).