Antimicrobial Resistance in Selected Foodborne Pathogens in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

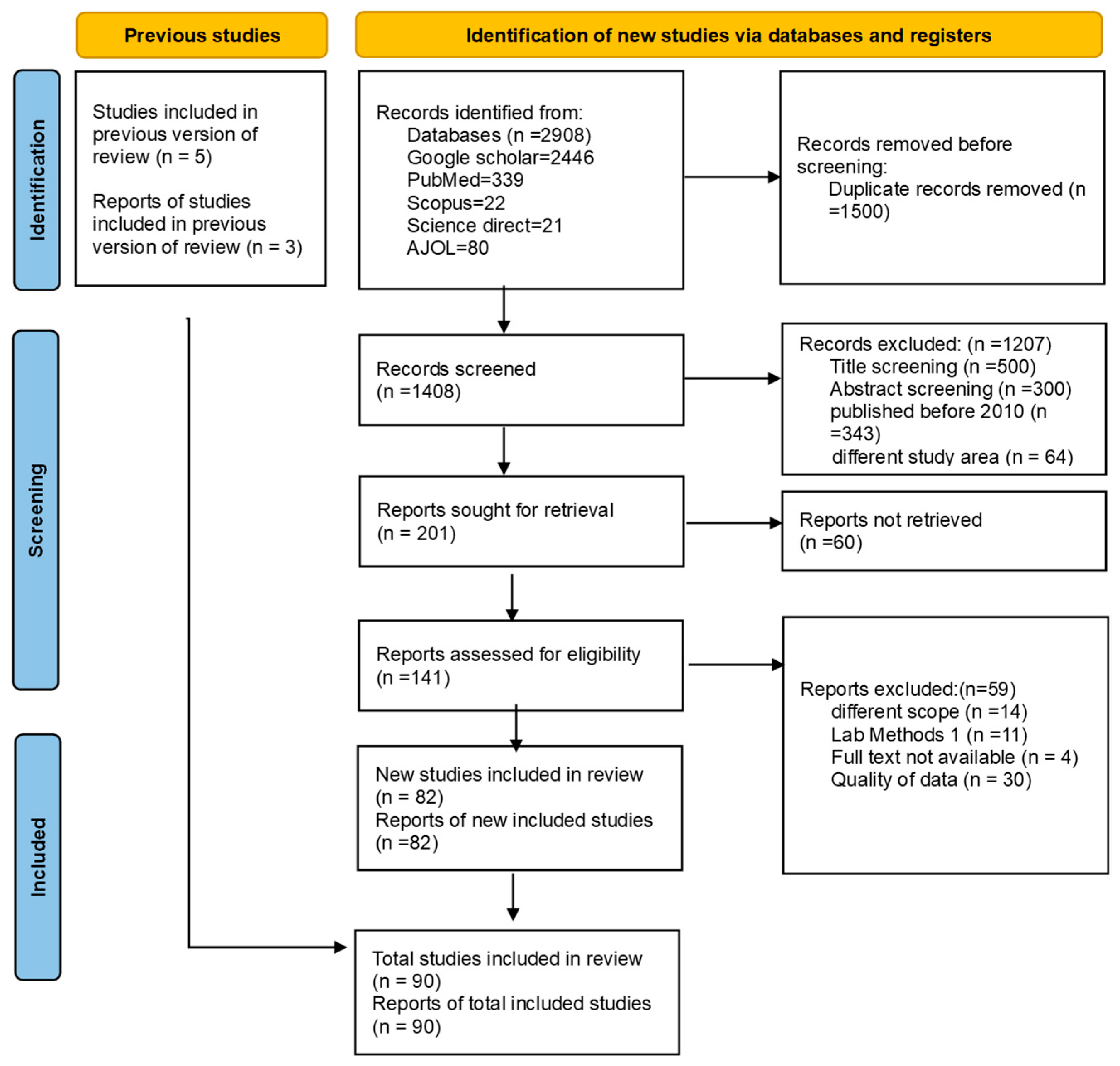

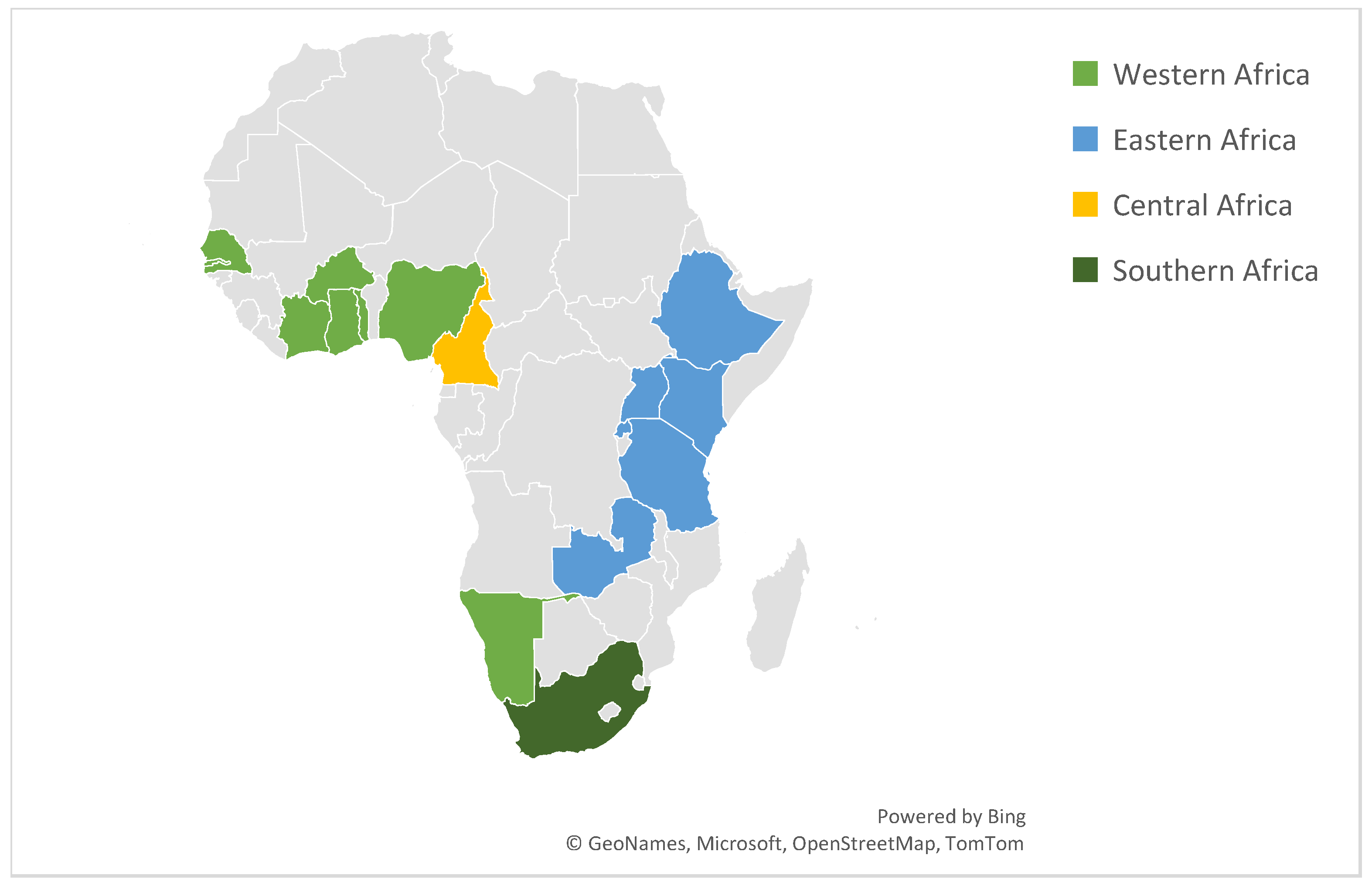

2.1. Characteristics of Included Studies and Their Distributions

2.2. Pathogen Prevalence

2.2.1. Subgroup Analysis of Pathogen Prevalence

2.2.2. Temporal Trend of Pathogen Prevalence

2.3. Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Prevalence

2.3.1. Subgroup Analysis of AMR Prevalence Rate by Country

2.3.2. Subgroup Analysis of AMR Prevalence by Pathogen Type

2.3.3. Subgroup Analysis of AMR Prevalence Rate by Classes

2.3.4. Temporal Trend of AMR Prevalence by Year

2.4. Multidrug Resistance (MDR) Prevalence

3. Discussion

3.1. Pathogen Prevalence

3.2. Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Prevalence

3.3. Multi Drug Resistance (MDR) Prevalence

3.4. Policy Implications

3.5. Limitations and Future Directions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Protocol Registration

- Population (P): Farm animals (cattle, poultry, pigs, goats, and sheep) and their derived food products (meat, milk, and eggs).

- Intervention/Exposure (I): Exposure to antimicrobial-resistant enteric pathogens (Salmonella spp., pathogenic E. coli, Campylobacter spp.).

- Comparator (C): Not applicable to prevalence analysis.

- Outcomes (O): Pooled prevalence of AMR, MDR, and pathogen isolation rates; resistance profiles by antibiotic class.

- Time (T): Studies published between 2010 and June 2025.

- Setting (S): Farms, slaughterhouses, markets, and retail outlets across SSA.

4.2. Search Strategy

4.3. Eligibility Criteria

- Reported laboratory-confirmed isolates of Salmonella spp., pathogenic E. coli, or Campylobacter spp.

- Originated from food-producing animals or derived food products (meat, milk, eggs, carcasses, ready-to-eat meat, cheese, or sausages).

- Employed standardized antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) methods (disk diffusion, broth/agar dilution, E-test, MIC, or VITEK) with interpretation based on CLSI or EUCAST guidelines.

- Provided quantitative data on AMR and/or MDR prevalence.

- Focused on non-bacterial pathogens (parasites, fungi, or viruses).

- Included wildlife, companion animals, or aquatic species.

- Were reviews, editorials, conference abstracts, or gray literature.

- Lacked explicit AMR/MDR data or prevalence estimates.

- Not published in English.

4.4. Data Extraction

- Sample size and number of positive isolates;

- Pathogen prevalence;

- AMR and MDR rates (MDR defined as resistance to ≥3 antibiotic classes);

- Geographic region and study setting.

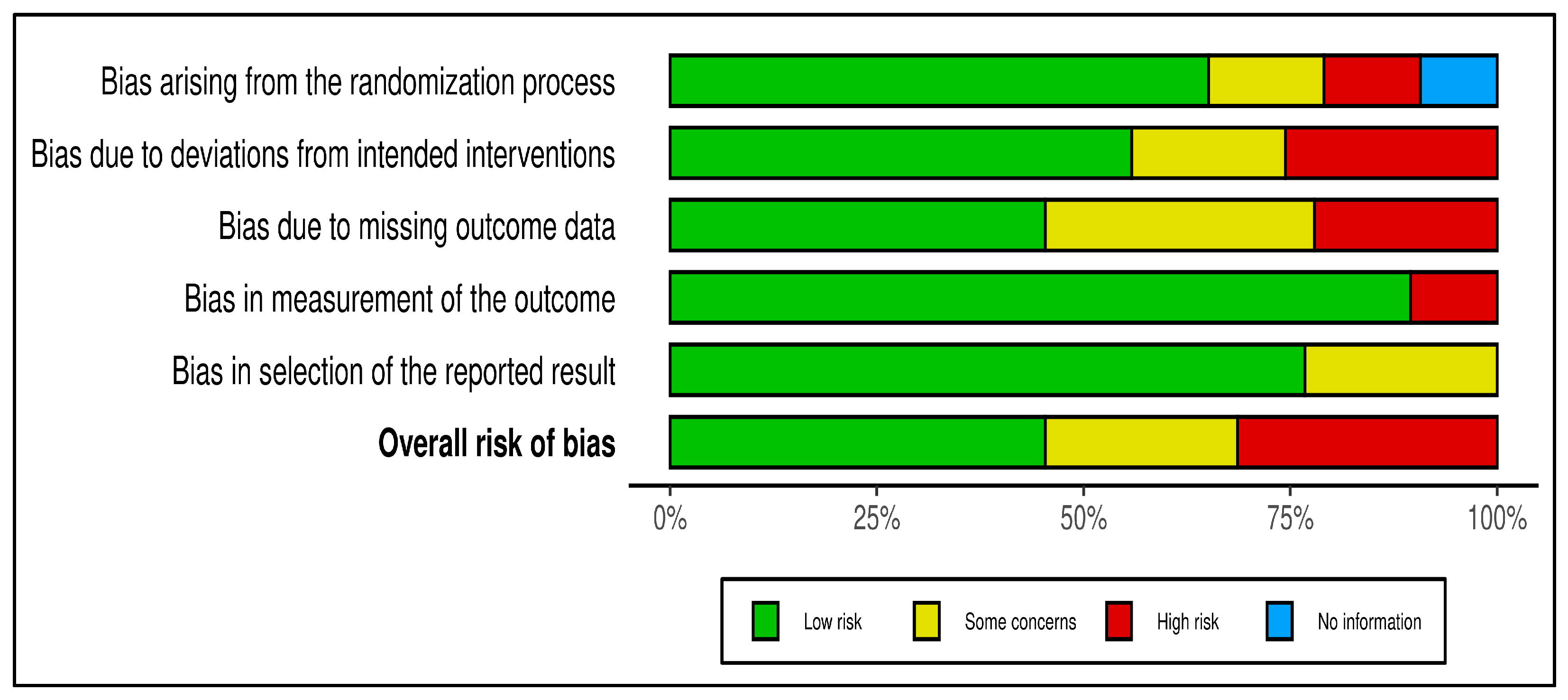

4.5. Quality Assessment

- Selection bias: representativeness of study population;

- Measurement bias: reliability of laboratory testing and AST interpretation;

- Reporting bias: completeness and transparency of data.

4.6. Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

4.7. Ethical Considerations and AI Disclosure

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| MDR | Multidrug Resistance |

| AST | Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| SSA | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| WOAH | World Organization for Animal Health (formerly OIE) |

| GLASS | Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System |

| AMRSNET | Africa Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network |

| LMICs | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| PICOTS | Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Timeframe, and Setting |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| Q | Cochran’s Heterogeneity Statistic |

| I2 | I-squared (Measure of Statistical Heterogeneity) |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| Β | Regression Coefficient |

| One Health | Integrated Approach Linking Human, Animal, and Environmental Health |

References

- Kalule, J.B.; Smith, A.; Vulindhlu, M.; Tau, N.; Nicol, M.; Keddy, K.; Robberts, L. Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of enteric bacterial pathogens in human and non-human sources in an urban informal settlement in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matakone, M.; Founou, R.C.; Founou, L.L.; Dimani, B.D.; Koudoum, P.L.; Fonkoua, M.C.; Boum-Ii, Y.; Gonsu, H.; Noubom, M. Multi-drug resistant (MDR) and extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli isolated from slaughtered pigs and slaughterhouse workers in Yaoundé, Cameroon. One Health 2024, 19, 100885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumu, N.O.; Muloi, D.M.; Moodley, A.; Ochien’G, L.; Watson, J.; Kiarie, A.; Ngeranwa, J.J.; Cumming, O.; Cook, E.A. Epidemiology of Antimicrobial-Resistant Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli Pathotypes from Children, Livestock and Food in Dagoretti South, Nairobi Kenya. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2025, 65, 107419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronald, C.; Matofari, J.W.; Nduko, J.M. Antimicrobial resistance of E. coli strains in ready-to-eat red meat products in Nakuru County, Kenya. Microbe 2023, 1, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeru, F.; Adamu, H.; Woldearegay, Y.H.; Tessema, T.S.; Hansson, I.; Boqvist, S. Occurrence, risk factors and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter from poultry and humans in central Ethiopia: A one health approach. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2025, 19, e0012916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoga, E.O.; Mshelbwala, P.P.; Ogugua, A.J.; Enemuo-Edo, E.C.; Onwumere-Idolor, O.S.; Ogunniran, T.M.; Bernard, S.N.; Ugwunwarua, J.C.; Anidobe, E.C.; Okoli, C.E.; et al. Campylobacter Colonisation of Poultry Slaughtered at Nigerian Slaughterhouses: Prevalence, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Risk of Zoonotic Transmission. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyene, A.M.; Alemie, Y.; Gizachew, M.; E Yousef, A.; Dessalegn, B.; Bitew, A.B.; Alemu, A.; Gobena, W.; Christian, K.; Gelaw, B. Serovars, virulence factors, and antimicrobial resistance profile of non-typhoidal Salmonella in the human-dairy interface in Northwest Ethiopia: A one health approach. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieye, Y.; Hull, D.M.; Wane, A.A.; Harden, L.; Fall, C.; Sambe-Ba, B.; Seck, A.; Fedorka-Cray, P.J.; Thakur, S. Genomics of human and chicken Salmonella isolates in Senegal: Broilers as a source of antimicrobial resistance and potentially invasive nontyphoidal salmonellosis infections. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokgophi, T.M.; Gcebe, N.; Fasina, F.; Adesiyun, A.A. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Salmonella isolates on chickens processed and retailed at outlets of the informal market in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Pathogens 2021, 10, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello, P.; Bjöersdorff, O.G.; Hansson, I.; Boqvist, S.; Erume, J. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistant Campylobacter spp. in broiler chicken carcasses and hygiene practises in informal urban markets in a low-income setting. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagambèga, A.B.; Dembélé, R.; Traoré, O.; Wane, A.A.; Mohamed, A.H.; Coulibaly, H.; Fall, C.; Bientz, L.; M’Zali, F.; Mayonnove, L.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of Environmental Extended Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae from Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, N.P.; Thomas, K.M.; Amani, N.B.; Benschop, J.; Bigogo, G.M.; Cleaveland, S.; Fayaz, A.; Hugho, E.A.; Karimuribo, E.D.; Kasagama, E.; et al. Population Structure and Antimicrobial Resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli Isolated from Humans with Diarrhea and from Poultry, East Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 2079–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, D.; Eibach, D.; Boahen, K.G.; Akenten, C.W.; Pfeifer, Y.; Zautner, A.E.; Mertens, E.; Krumkamp, R.; Jaeger, A.; Flieger, A.; et al. Fluoroquinolone-Resistant Salmonella enterica, Campylobacter spp., and Arcobacter butzleri from Local and Imported Poultry Meat in Kumasi, Ghana. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2019, 16, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainda, G.; Bessell, P.R.; Muma, J.B.; McAteer, S.P.; Chase-Topping, M.E.; Gibbons, J.; Stevens, M.P.; Gally, D.L.; Bronsvoort, B.M.d.C. Prevalence and patterns of antimicrobial resistance among Escherichia coli isolated from Zambian dairy cattle across different production systems. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikari, A.B.; Obiri-Danso, K.; Frimpong, E.H.; Krogfelt, K.A. Antibiotic Resistance of Campylobacter Recovered from Faeces and Carcasses of Healthy Livestock. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 4091856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambuyi, K. Occurrence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Campylobacter spp. Isolates from Beef Cattle in Gauteng and North West Provinces, South Africa. Master’s Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kagambèga, A.; Thibodeau, A.; Trinetta, V.; Soro, D.K.; Sama, F.N.; Bako, É.; Bouda, C.S.; N’diaye, A.W.; Fravalo, P.; Barro, N. Salmonella spp. and Campylobacter spp. in poultry feces and carcasses in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 1601–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinduti, A.P.; Ayodele, O.; Motayo, B.O.; Obafemi, Y.D.; Isibor, P.O.; Aboderin, O.W. Cluster analysis and geospatial mapping of antibiotic resistant Escherichia coli O157 in southwest Nigerian communities. One Health 2022, 15, 100447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muligisa-Muonga, E.; Mainda, G.; Mukuma, M.; Kwenda, G.; Hang’ombe, B.; Flavien, B.N.; Phiri, N.; Mwansa, M.; Munyeme, M.; Muma, J.B.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli and Salmonella isolated from retail broiler chicken carcasses in Zambia. J. Epidemiol. Res. 2021, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabode, H.O.; Mailafia, S.; Ogbole, M.E.; Okoh, G.R.; Ifeanyi, C.I.; Onigbanjo, H.O.; Ugbaja, I.B. Isolation and Antibiotic Susceptibility of Campylobacter Species from Cattle Offals in Gwagwalada Abattoir, Abuja-FCT Nigeria. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbor, O.; Ajayi, A.; Zautner, A.E.; Smith, S.I. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Campylobacter coli isolated from poultry farms in Lagos Nigeria—A pilot study. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2019, 9, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, M.K.; Muigai, A.W.T.; Ndung’u, P.; Kariuki, S. Investigating Carriage, Contamination, Antimicrobial Resistance and Assessment of Colonization Risk Factors of Campylobacter spp. in Broilers from Selected Farms in Thika, Kenya. Microbiol. Res. J. Int. 2019, 27, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahamanyi, N.; Habimana, A.M.; Harerimana, J.P.; Mukayisenga, J.; Ntwali, S.; Umuhoza, A.; Nsengiyumva, E.; Irimaso, E.; Shimirwa, J.B.; Pan, C.-H.; et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of thermophilic Campylobacter species from human, pig, and chicken feces in Rwanda. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1570290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesonga, S.M.; Muluvi, G.M.; Okemo, P.O.; Kariuki, S. Antibiotic resistant Salmonella and Escherichia coli isolated from indiginous Gallus domesticus in Nairobi, Kenya. East Afr. Med. J. 2010, 87, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uaboi-Egbenni, P.O.; Bessong, P.O.; Samie, A.; Obi, C.L. Potentially pathogenic Campylobacter species among farm animals in rural areas of Limpopo province, South Africa: A case study of chickens and cattles. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2012, 6, 2835–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uaboi-Egbenni, P.O.; Bessong, P.O.; Samie, A.; Obi, C.L. Prevalence, haemolysis and antibiograms of Campylobacters isolated from pigs from three farm settlements in Venda region, Limpopo province, South Africa. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uaboi-Egbenni, P.O.; Bessong, P.O.; Samie, A.; Obi, C.L. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Campylobacter jejuni and coli isolated from diarrheic and non-diarrheic goat faeces in Venda region, South Africa. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 14116–14124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uaboi-Egbenni, P.O.; Bessong, P.O.; Samie, A.; Obi, C.L. Campylobacteriosis in sheep in farm settlements in the Vhembe district of South Africa. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2010, 4, 2109–2117. [Google Scholar]

- Salihu, M.D.; Junaidu, A.U.; Magaji, A.A.; Yakubu, Y. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Thermophilic Campylobacter Isolates from Commercial Broiler Flocks in Sokoto, Nigeria. Res. J. Vet. Sci. 2012, 5, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rene, K.A.; Adjehi, D.; Timothee, O.; Tago, K.; Marcelin, D.K.; Ignace-Herve, M.E. Serotypes and antibiotic resistance of Salmonella spp. isolated from poultry carcass and raw gizzard sold in markets and catering in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci 2014, 3, 764–772. [Google Scholar]

- Okunlade, A.O.; Ogunleye, A.O.; Jeminlehin, F.O.; Ajuwape, A.T.P. Occurrence of Campylobacter species in beef cattle and local chickens and their antibiotic profiling in Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2015, 9, 1473–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonga, H.E.; Muhairwa, A.P. Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility of thermophilic Campylobacter isolates from free range domestic duck (Cairina moschata) in Morogoro municipality, Tanzania. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2010, 42, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigatu, S.; Mequanent, A.; Tesfaye, R.; Garedew, L. Prevalence and Drug Sensitivity Pattern of Campylobacter jejuni Isolated from Cattle and Poultry in and Around Gondar Town, Ethiopia. Glob. Vet. 2015, 14, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resource Type Themes Keywords African Union AMR Landmark Report: Voicing African Priorities on the Active Pandemic. Available online: https://africacdc.org/download/african-union-amr-landmark-report-voic (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The FAO Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance 2021–2025; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Meza, M.E.; Galarde-López, M.; Carrillo-Quiróz, B.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.M. Antimicrobial resistance: One Health approach. Vet. World 2022, 15, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Organisation for Animal Health. OIE Standards, Guidelines and Resolution on Antimicrobial Resistance and the Use of Antimicrobial Agents; OIE: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sartorius, B.; Gray, A.P.; Weaver, N.D.; Aguilar, G.R.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Ikuta, K.S.; Mestrovic, T.; Chung, E.; Wool, E.E.; Han, C.; et al. The burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in the WHO African region in 2019: A cross-country systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e201–e216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; OIE; WHO. Monitoring and Evaluation of the Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance Framework and Recommended Indicators; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Essack, P.S.; Essack, S.Y. AMR Surveillance in Africa: Are We There Yet? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 152, 107828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajumbula, H.M.; Amoako, D.G.; Tessema, S.K.; Aworh, M.K.; Chikuse, F.; Okeke, I.N.; Okomo, U.; Jallow, S.; Egyir, B.; Kanzi, A.M.; et al. Enhancing clinical microbiology for genomic surveillance of antimicrobial resistance implementation in Africa. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2024, 13, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onohuean, H.; Olot, H.; Onohuean, F.E.; Bukke, S.P.N.; Akinsuyi, O.S.; Kade, A. A scoping review of the prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant pathogens and signatures in ready-to-eat street foods in Africa: Implications for public health. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1525564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, N.; Todo, A. Civil Society Report on Sustainable Development Goals: Agenda 2030. Sustainable Development Goals: Agenda 2030 A Civil Society Report INDIA 2017. Available online: https://www.gcap.global/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Sustainable-Development-Goals-2018.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Antimicrobial Resistance Control—Africa CDC. Available online: https://africacdc.org/antimicrobial-resistance/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Strategic Framework for Collaboration on Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240045408 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Mathole, M.A.; Muchadeyi, F.C.; Mdladla, K.; Malatji, D.P.; Dzomba, E.F.; Madoroba, E. Presence, distribution, serotypes and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Salmonella among pigs, chickens and goats in South Africa. Food Control 2017, 72, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komba, E.V.G.; Mdegela, R.H.; Msoffe, P.L.M.; Matowo, D.E.; Maro, M.J. Occurrence, species distribution and antimicrobial resistance of thermophilic Campylobacter isolates from farm and laboratory animals in Morogoro, Tanzania. Vet. World 2014, 7, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iroha, I.R.; Ugbo, E.C.; Ilang, D.C.; Oji, A.E.; Ayogu, T.E. Bacteria contamination of raw meat sold in Abakaliki, Ebonyi State Nigeria. J. Public Health Epidemiol. 2011, 3, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Garedew, L.; Hagos, Z.; Addis, Z.; Tesfaye, R.; Zegeye, B. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Salmonella isolates in association with hygienic status from butcher shops in Gondar town, Ethiopia. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2015, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewnetu, D.; Mihret, A. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Campylobacter Isolates from Humans and Chickens in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2010, 7, 667–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanyalew, Y.; Asrat, D.; Amavisit, P.; Loongyai, W. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Thermophilic Campylobacter Isolated from Sheep at Debre Birhan, North-Shoa, Ethiopia. Nat. Sci. 2013, 47, 551–560. [Google Scholar]

- Bester, L.A.; Essack, S.Y. Observational study of the prevalence and antibiotic resistance of Campylobacter spp. from different poultry production systems in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J. Food Prot. 2012, 75, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, B.; Ashenafi, M. Distribution of drug resistance among enterococci and Salmonella from poultry and cattle in Ethiopia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2010, 42, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawa, I.; Tchamba, G.B.; Bagre, T.; Bouda, S.; Konate, A.; Bako, E.; Kagambega, A.; Zongo, C.; Somda, M.; Savadogo, A.; et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Salmonella enterica strains isolated from raw beef, mutton and intestines sold in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. J. Appl. Biosci. 2015, 95, 8966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bata, S.I.; Karshima, N.S.; Yohanna, J.; Dashe, M.; Pam, V.A.; Ogbu, K.I. Isolation and antibiotic sensitivity patterns of Salmonella species from raw beef and quail eggs from farms and retail outlets in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria. J. Vet. Med. Anim. Health 2016, 8, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, S.; Zewde, B.M. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Salmonella enterica serovars isolated from slaughtered cattle in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2012, 44, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, A.O.; Egbebi, A.O. Antibiotic sucseptibility of Salmonella Typhi and Klebsiella pneumoniae from poultry and local birds in Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti-State, Nigeria. Ann. Biol. Res. 2011, 2, 431–437. [Google Scholar]

- Adeyanju, G.T.; Ishola, O. Salmonella and Escherichia coli contamination of poultry meat from a processing plant and retail markets in Ibadan, Oyo state, Nigeria. Springerplus 2014, 3, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemisi, A.O.; Oyebode, A.T.; Margaret, A.A.; Justina, J.B. Prevalence of Arcobacter, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella species in Retail Raw Chicken, Pork, Beef and Goat meat in Osogbo, Nigeria. Sierra Leone J. Biomed. Res. 2011, 3, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Addis, Z.; Kebede, N.; Worku, Z.; Gezahegn, H.; Yirsaw, A.; Kassa, T. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella isolated from lactating cows and in contact humans in dairy farms of Addis Ababa: A cross sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibril, A.H.; Sarkinfulani, S.A.; Ballah, F.M.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Garba, B.; Garba, S.; Abubakar, Y. Molecular prevalence and resistance profile of Escherichia coli from poultry in Niger State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Environ. 2025, 20, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fashae, K.; Ogunsola, F.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Hendriksen, R.S. Antimicrobial susceptibility and serovars of Salmonella from chickens and humans in Ibadan, Nigeria. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2010, 4, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baluka, S.A.; Musisi, L.N.; Buyinza, L.S.Y.; Ejobi, F. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Foodborne Pathogens in Sentinel Dairy Farms. Eur. J. Agric. Food Sci. 2021, 3, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; OIE; WHO. Monitoring Global Progress on Antimicrobial Resistance: Tripartite AMR Country Self-Assessment Survey; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland; FAO: Rome, Italy; OIE: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Collignon, P.C.; Conly, J.M.; Andremont, A.; McEwen, S.A.; Aidara-Kane, A. World Health Organization Advisory Group on Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance (WHO-AGISAR). World Health Organization Ranking of Antimicrobials According to Their Importance in Human Medicine: A Critical Step for Developing Risk Management Strategies to Control Antimicrobial Resistance from Food Animal Production. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, 1087–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Africa CDC. Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Guidance for the African Region; Africa CDC: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Founou, L.L.; Founou, R.C.; Essack, S.Y. Antimicrobial Resistance in the farm-to-plate Continuum—More Than a Food Safety Issue. Future Sci. OA 2021, 7, FSO692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO; FAO; OIE. World Health Organization Collaboration with OIE on Foodborne Antimicrobial Resistance: Role of the Environment, Crops and Biocides; Meeting Report 34 Microbiological Risk Assessment Series; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland; FAO: Rome, Italy; OIE: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Prioritization of Pathogens to Guide Discovery, Research and Development of New Antibiotics for Drug-Resistant Bacterial Infections, Including Tuberculosis; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nyabundi, D.; Onkoba, N.; Kimathi, R.; Nyachieo, A.; Juma, G.; Kinyanjui, P.; Kamau, J. Molecular characterization and antibiotic resistance profiles of Salmonella isolated from fecal matter of domestic animals and animal products in Nairobi. Trop. Dis. Travel Med. Vaccines 2017, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agumah, N.B.; Effendi, M.H.; Tyasningsih, W.; Witaningrum, A.M.; Ugbo, E.N.; Agumah, O.B.; Ahmad, R.Z.; Ugbo, A.I.; Nwagwu, C.S.; Khairullah, A.R.; et al. Distribution of cephalosporin-resistant Campylobacter species isolated from meat sold in Abakaliki, Nigeria. Open Vet. J. 2025, 15, 1615–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemeda, B.A.; Wieland, B.; Alemayehu, G.; Knight-Jones, T.J.D.; Wodajo, H.D.; Tefera, M.; Kumbe, A.; Olani, A.; Abera, S.; Amenu, K. Antimicrobial Resistance of Escherichia coli Isolates from Livestock and the Environment in Extensive Smallholder Livestock Production Systems in Ethiopia. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katakweba, A.A.S.; Muhairwa, A.P.; Lupindu, A.M.; Damborg, P.; Rosenkrantz, J.T.; Minga, U.M.; Mtambo, M.M.A.; Olsen, J.E. First Report on a Randomized Investigation of Antimicrobial Resistance in Fecal Indicator Bacteria from Livestock, Poultry, and Humans in Tanzania. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touglo, K.; Djeri, B.; Sina, H.; Boya, B.; Ayadokoun, G.G.; Baba-Moussa, L.; Ameyapoh, Y. First detection of resistance genes and virulence factors in Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. in Togo: The case of imported chicken and frozen by-products. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashim, B.J.S.; Ssajjakambwe, P.; Ntulume, I.; Pius, T. Escherichia coli isolated from raw cow milk at selected collection centres in Bushenyi district, Western Uganda: A potential risk to human health. Res. Sq. 2024; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manishimwe, R.; Moncada, P.M.; Musanayire, V.; Shyaka, A.; Scott, H.M.; Loneragan, G.H. Antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli and Salmonella from the feces of food animals in the east province of Rwanda. Animals 2021, 11, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyolimati, C.A.; Mayito, J.; Obuya, E.; Acaye, A.S.; Isingoma, E.; Kibombo, D.; Byonanebye, D.M.; Walwema, R.; Musoke, D.; Orach, C.G.; et al. Prevalence and factors associated with multidrug resistant Escherichia coli carriage on chicken farms in west Nile region in Uganda: A cross-sectional survey. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2025, 5, e0003802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, P.B.; Essodina, T.; Malibida, D.; Adeline, D.; Rianatou, B.A. Antibiotic resistance of enterobacteria (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp. and Salmonella spp.) isolated from healthy poultry and pig farms in peri-urban area of Lome, Togo. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 14, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, J.; Ndung’u, P.; Muigai, A.; Kiiru, J. Antimicrobial resistance profiles and genetic basis of resistance among non-fastidious Gram-negative bacteria recovered from ready-to-eat foods in Kibera informal housing in Nairobi, Kenya. Access Microbiol. 2021, 3, 000236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sime, M.G. Occurrence and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Salmonella in Fecal and Carcass Swab Samples of Small Ruminants at Addis Ababa Livestock Market. J. Vet. Sci. 2021, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Eguale, T.; Birungi, J.; Asrat, D.; Njahira, M.N.; Njuguna, J.; Gebreyes, W.A.; Gunn, J.S.; Djikeng, A.; Engidawork, E. Fecal prevalence, serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonellae in dairy cattle in central Ethiopia. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waktole, H.; Alemie, Y.; Gizachew, M.; Yousef, A.E.; Dessalegn, B.; Bitew, A.B.; Alemu, A.; Gobena, W.; Christian, K.; Gelaw, B. Prevalence, Molecular Detection, and Antimicrobial Resistance of Salmonella Isolates from Poultry Farms across Central Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study in Urban and Peri-Urban Areas. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akenten, C.W.; Ofori, L.A.; Mbwana, J.; Sarpong, N.; May, J.; Thye, T.; Obiri-Danso, K.; Paintsil, E.K.; Philipps, R.O.; Eibach, D.; et al. Characterization of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli From Domestic Free-Range Poultry in Agogo, Ghana. Res. Sq. 2022; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, A.S.; Gharedaghi, Y.; Mumed, B.A. Isolation and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test of Non-typhoidal Salmonella from Raw Bovine Milk and Assessments of Hygienic Practices in Gursum District, Eastern Hararghe, Ethiopia. Int. J. Med. Parasitol. Epidemiol. Sci. 2025, 6, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takele, S.; Woldemichael, K.; Gashaw, M.; Tassew, H.; Yohannes, M.; Abdissa, A. Prevalence and drug susceptibility pattern of Salmonella isolates from apparently healthy slaughter cattle and personnel working at the Jimma municipal abattoir, south-West Ethiopia. Trop. Dis. Travel Med. Vaccines 2018, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwambete, K.D.; Stephen, S. Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of Bacteria Isolated from Chicken Droppings in Dar es Salaam. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci 2015, 7, 268–271. [Google Scholar]

- Cyuzuzo, E.; Amosun, E.A.; Byukusenge, M.; Musanayire, V. Antimicrobial Resistance Profiling of Escherichia coli Isolated from Chickens in Northern Province of Rwanda. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2023, 26, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, A.; Sharew, B.; Tilahun, M.; Million, Y. Isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility profile of Salmonella species from slaughtered cattle carcasses and abattoir personnel at Dessie, municipality Abattoir, Northeast Ethiopia. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndukui, J.G.; Gikunju, J.K.; Aboge, G.O.; Mwaniki, J.; Kariuki, S.; Mbaria, J.M. Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Selected Enterobacteriaceae Isolated from Commercial Poultry Production Systems in Kiambu County, Kenya. Pharmacol. Pharm. 2021, 12, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwasinga, W.; Shawa, M.; Katemangwe, P.; Chambaro, H.; Mpundu, P.; M’kandawire, E.; Mumba, C.; Munyeme, M. Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli from Raw Cow Milk in Namwala District, Zambia: Public Health Implications. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiiti, R.W.; Komba, E.V.; Msoffe, P.L.; Mshana, S.E.; Rweyemamu, M.; Matee, M.I.N. Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of Escherichia coli Isolated from Broiler and Layer Chickens in Arusha and Mwanza, Tanzania. Int. J. Microbiol. 2021, 2021, 6759046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyalo, J.A.; Gebreyes, W.A.; Mutai, W.; Anzala, O.; Ponte, A.; Merdadus, J.; Kariuki, S. Detection of Fluoroquinolone and other Multi-drug Resistance Determinants in Multi-drug Resistant Non-Typhoidal Salmonella Isolated from Swine. Afr. J. Health Sci. 2020, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Haile, A.F.; Kebede, D.; Wubshet, A.K. Prevalence and antibiogram of Escherichia coli O157 isolated from bovine in Jimma, Ethiopia: Abattoirbased survey. Ethiop. Vet. J. 2017, 21, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kebbeh, A.; Anderson, B.; Jallow, H.S.; Sagnia, O.; Mendy, J.; Camara, Y.; Darboe, S.; Sambou, S.M.; Baldeh, I.; Sanneh, B. Prevalence of Highly Multi-Drug Resistant Salmonella Fecal Carriage Among Food Handlers in Lower Basic Schools in The Gambia. Int. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2017, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ramatla, T.; Taioe, M.O.; Thekisoe, O.M.M.; Syakalima, M. Confirmation of antimicrobial resistance by using resistance genes of isolated Salmonella spp. in chicken houses of north west, South Africa. World’s Vet. J. 2019, 9, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaonga, N.; Hang’ombe, B.M.; Lupindu, A.M.; Hoza, A.S. Detection of CTX-M-Type Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Producing Salmonella Typhimurium in Commercial Poultry Farms in Copperbelt Province, Zambia. Ger. J. Vet. Res. 2021, 1, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilangale, R.; Kaaya, G.; Chimwamurombe, P. Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Salmonella Strains Isolated from Beef in Namibia. Br. Microbiol. Res. J. 2016, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtonga, S.; Nyirenda, S.S.; Mulemba, S.S.; Ziba, M.W.; Muuka, G.M.; Fandamu, P. Epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance of pathogenic E. coli in chickens from selected poultry farms in Zambia. J. Zoonotic Dis. 2021, 5, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guesh, M. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Salmonella species from lactating cows in dairy farm of Bahir Dar Town, Ethiopia. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 11, 1578–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshatu, F.; Fanta, D.; Aklilu, F.; Getachew, T.; Nebyu, M. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Salmonella isolates from apparently healthy slaughtered goats at Dire Dawa municipal abattoir, Eastern Ethiopia. J. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2015, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disassa, N.; Sibhat, B.; Mengistu, S.; Muktar, Y.; Belina, D. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Pattern of E. coli O157:H7 Isolated from Traditionally Marketed Raw Cow Milk in and around Asosa Town, Western Ethiopia. Vet. Med. Int. 2017, 2017, 7581531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. GLASS Whole-Genome Sequencing for Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sourd, G.L.; Ricker, B. Cartography for global sustainable development agendas: Informing public policies with geospatial information and knowledge for people, places and planet*. Int. J. Cartogr. 2025, 11, 428–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pathogen | No. Studies (n) | N | Positive Isolates | Pathogen (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmonella spp. | 41 | 96,721 | 18,782 | 17.6 |

| Pathogenic E. coli | 31 | 119,859 | 58,231 | 44.0 |

| Campylobacter spp. | 30 | 175,704 | 27,073 | 18.4 |

| Total | 90 | 392,284 | 104,086 | 53.1 |

| Pathogen Prevalence | Heterogeneity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Regions | k † | in % (95% CI) | τ2 | I2 (%) | Q |

| Burkina Faso | West Africa | 68 | 21.0 (17.6–24.6) | 0.0205 | 87.4 | 532.6 |

| Cameroon | Central Africa | 12 | 22.4 (14.2–31.8) | 0.0256 | 92.8 | 152.14 |

| Cote d’Ivoire | West Africa | 23 | 33.1 (25.0–41.6) | 0.0402 | 97.0 | 732.05 |

| Ethiopia | East Africa | 296 | 24.7 (21.1–28.4) | 0.1317 | 99.4 | 52,828.1 |

| Gambia | West Africa | 12 | 2.6 (2.6–2.6) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Ghana | West Africa | 156 | 9.5 (8.1–11.0) | 0.0223 | 97.3 | 5703.03 |

| Kenya | East Africa | 172 | 21.0 (17.8–24.4) | 0.0695 | 98.6 | 12,029.7 |

| Namibia | Southern Africa | 7 | 32.9 (29.9–36.0) | 0.0002 | 12.7 | 6.87 |

| Nigeria | West Africa | 201 | 21.8 (18.8–25.0) | 0.064 | 96.2 | 5215.42 |

| Rwanda | East Africa | 77 | 21.3 (19.1–23.7) | 0.0145 | 95.0 | 1515.27 |

| Senegal | West Africa | 11 | 37.7 (37.7–37.7) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| South Africa | Southern Africa | 231 | 20.1 (17.6–22.8) | 0.0571 | 97.4 | 8764.12 |

| Tanzania | East Africa | 122 | 66.9 (61.4–72.2) | 0.0972 | 97.8 | 5384.47 |

| Togo | West Africa | 88 | 34.3 (27.8–41.0) | 0.1019 | 97.8 | 3903.23 |

| Uganda | East Africa | 38 | 85.6 (62.3–97.4) | 0.2877 | 99.3 | 2884.89 |

| Zambia | Southern Africa | 41 | 23.7 (0.141–0.348) | 0.1461 | 99.4 | 6891.92 |

| Parameter | Estimate (β) | SE | z-Value | p-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −155.75 | 19.88 | −7.84 | <0.0001 | −194.71 to −116.80 |

| Year | 0.0765 | 0.0098 | 7.77 | <0.0001 | 0.0572–0.0958 |

| AMR Prevalence | Heterogeneity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Region | k † | in % (95% CI) | τ2 | I2 (%) | Q |

| Burkina Faso | West Africa | 68 | 26.4 (19.0–34.5) | 0.1205 | 98.7 | 5129.95 |

| Cameroon | Central Africa | 12 | 63.1 (27.1–92.4) | 0.3334 | 99.4 | 1852.05 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | West Africa | 23 | 25.3 (15.0–37.1) | 0.0849 | 98.2 | 1219.93 |

| Ethiopia | East Africa | 296 | 30.9 (26.3–35.6) | 0.1865 | 99.3 | 43,293.93 |

| Gambia | West Africa | 12 | 38.4 (11.9–69.3) | 0.2454 | 99.8 | 5415.81 |

| Ghana | West Africa | 156 | 55.3 (47.8–62.7) | 0.2264 | 99.8 | 62,372.45 |

| Kenya | East Africa | 172 | 28.4 (23.6–33.4) | 0.1272 | 99.1 | 18,972.39 |

| Namibia | Southern Africa | 7 | 4.2 (0.1–12.9) | 0.0278 | 96.3 | 164.30 |

| Nigeria | West Africa | 201 | 50.5 (44.3–56.8) | 0.1972 | 99.3 | 29,634.48 |

| Rwanda | East Africa | 77 | 14.5 (8.6–21.7) | 0.1675 | 99.6 | 20,743.17 |

| Senegal | West Africa | 11 | 18.7 (6.4–35.6) | 0.0799 | 98.9 | 893.40 |

| South Africa | Southern Africa | 231 | 25.6 (20.5–31.1) | 0.2128 | 99.5 | 45,963.07 |

| Tanzania | East Africa | 122 | 41.5 (34.9–48.4) | 0.1419 | 99.3 | 16,562.13 |

| Togo | West Africa | 88 | 22.0 (15.1–29.8) | 0.1698 | 98.4 | 5300.42 |

| Uganda | East Africa | 54 | 45.9 (28.2–65.4) | 0.1557 | 98.5 | 1783.2 |

| Zambia | Southern Africa | 41 | 25.6 (14.2–39.0) | 0.2025 | 99.6 | 9920.30 |

| AMR Prevalence | Heterogeneity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | k † | in % (95% CI) | τ2 | I2 (%) | Q |

| Campylobacter spp. | 660 | 43.5 (40.2–46.9) | 0.1929 | 99.6 | 150,877.5 |

| Escherichia coli | 417 | 22.8 (19.6–26.2) | 0.1631 | 99.4 | 70,412.52 |

| Salmonella spp. | 478 | 29.1 (25.5–32.9) | 0.1977 | 99.3 | 71,610.12 |

| AMR Prevalence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial Class | k † | In % (95% CI) | τ2 | I2 (%) | Q |

| Aminoglycosides | 257 | 23.1 (19.4–27.0) | 0.1287 | 99.1 | 27,097.3 |

| Fluoroquinolones | 280 | 23.7 (19.8–27.8) | 0.1526 | 99.3 | 38,331.27 |

| Folate Pathway Inhibitors | 136 | 49.8 (42.6–56.9) | 0.1758 | 99.5 | 25,708.75 |

| Glycopeptides | 6 | 72.6 (29.9–98.9) | 0.1746 | 99.6 | 1157.82 |

| Lincosamides | 4 | 35.6 (20.2–52.7) | 0.0114 | 96.1 | 76.24 |

| Macrolides | 100 | 39.4 (30.3–48.8) | 0.2254 | 99.7 | 30,606.17 |

| Nitrofurans | 18 | 40.5 (19.8–63.0) | 0.2056 | 99.6 | 3995.84 |

| Phenicol’s | 96 | 20.0 (14.2–26.4) | 0.1355 | 99.4 | 14,651.03 |

| Phosphonic Acids | 2 | 5.3 (0.00–100.0) | 0.0323 | 95.7 | 23.51 |

| Pleuromutilins | 1 | 39.8 (33.9–45.9) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Polymyxins | 8 | 9.0 (0.00–40.5) | 0.194 | 98.1 | 368.98 |

| Polypeptide Antibiotics | 2 | 88.0 (0.06–100.0) | 0.0148 | 88.9 | 9.02 |

| Rifamycin’s | 2 | 100.0 (98.7–100.0) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.02 |

| Tetracyclines | 169 | 53.5 (46.8–60.2) | 0.1894 | 99.5 | 32,620.34 |

| β-Lactam Antibiotics | 471 | 34.7 (30.6–38.8) | 0.2247 | 99.6 | 119,206.85 |

| Parameter | Estimate (β) | SE | z-Value | p-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −161.6759 | 26.1326 | −6.1868 | <0.0001 | −212.8948 to −110.4570 |

| Year | 0.0785 | 0.0129 | 6.0617 | <0.0001 | 0.0531 to 0.1038 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hassen, K.A.; Fafetine, J.; Augusto, L.; Mandomando, I.; Garrine, M.; Sileshi, G.W. Antimicrobial Resistance in Selected Foodborne Pathogens in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010087

Hassen KA, Fafetine J, Augusto L, Mandomando I, Garrine M, Sileshi GW. Antimicrobial Resistance in Selected Foodborne Pathogens in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010087

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassen, Kedir A., Jose Fafetine, Laurinda Augusto, Inacio Mandomando, Marcelino Garrine, and Gudeta W. Sileshi. 2026. "Antimicrobial Resistance in Selected Foodborne Pathogens in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010087

APA StyleHassen, K. A., Fafetine, J., Augusto, L., Mandomando, I., Garrine, M., & Sileshi, G. W. (2026). Antimicrobial Resistance in Selected Foodborne Pathogens in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antibiotics, 15(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010087