The Emergence of blaNDM-Encoding Plasmids in Enterobacteriaceae Isolated from Shared Water Resources for Livestock and Human Utilization in Central Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sampling and Detection of CPE

4.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility

4.3. WGS and Plasmid Conjugation Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| AST | Antibiotic Susceptibility Test |

| blaNDM | New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamase Gene |

| CPE | Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae |

| LB | Luria–Bertani |

| MALDI-TOF MS | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry |

| MDR | Multidrug Resistance |

| MIC | Minimal Inhibitory Concentration |

| MLST | Multi-Locus Sequence Type |

| NDM | New Delhi Metallo-β-lactamase |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| WGS | Whole-Genome Sequencing |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Zhao, Q.; Berglund, B.; Zou, H.; Zhou, Z.; Xia, H.; Zhao, L.; Nilsson, L.E.; Li, X. Dissemination of bla(NDM-5) via IncX3 plasmids in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae among humans and in the environment in an intensive vegetable cultivation area in eastern China. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 273, 116370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Chen, J.; Sun, S.; Deng, S. Mortality-Related Risk Factors and Novel Antimicrobial Regimens for Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Infections: A Systematic Review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 6907–6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- WHO. WHO Publishes List of Bacteria for Which New Antibiotics Are Urgently Needed; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Yong, D.; Toleman, M.A.; Giske, C.G.; Cho, H.S.; Sundman, K.; Lee, K.; Walsh, T.R. Characterization of a New Metallo-beta-lactamase gene, bla(NDM-1), and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 5046–5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, S.S.; Harnod, D.; Hsueh, P.R. Global Threat of Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 823684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ma, J.; Zhou, W.; Wu, J.; Liu, X.; Lin, J.; Ji, X.; Lin, H.; Wang, J.; Jiang, H.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Large-Scale Studies on Antimicrobial Resistance and Molecular Characterization of Escherichia coli from Food Animals in Developed Areas of Eastern China. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02015-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, A.L.; de Oliveira, P.M.; Faria-Junior, C.; Alves, E.G.; de Castro e Caldo Lima, G.R.; da Costa Lamounier, T.A.; Haddad, R.; de Araújo, W.N. Environmental spreading of clinically relevant carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli: The occurrence of blaKPC-or-NDM strains relates to local hospital activities. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, B.; Chang, J.; Cao, L.; Luo, Q.; Xu, H.; Lyu, W.; Qian, M.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Q.; Xia, X.; et al. Characterization of an NDM-5 carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli ST156 isolate from a poultry farm in Zhejiang, China. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, R.; Akeda, Y.; Sakamoto, N.; Takeuchi, D.; Sugawara, Y.; Yamamoto, N.; Kerdsin, A.; Matsumoto, Y.; Motooka, D.; Laolerd, W.; et al. A Nationwide Plasmidome Surveillance in Thailand Reveals a Limited Variety of New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Clones and Spreading Plasmids. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2022, 60, e01080-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, D.; Kerdsin, A.; Akeda, Y.; Sugawara, Y.; Sakamoto, N.; Matsumoto, Y.; Motooka, D.; Ishihara, T.; Nishi, I.; Laolerd, W.; et al. Nationwide surveillance in Thailand revealed genotype-dependent dissemination of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales. Microb. Genom. 2022, 8, 000797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yungyuen, T.; Chatsuwan, T.; Plongla, R.; Kanthawong, S.; Yordpratum, U.; Voravuthikunchai, S.P.; Chusri, S.; Saeloh, D.; Samosornsuk, W.; Suwantarat, N.; et al. Nationwide Surveillance and Molecular Characterization of Critically Drug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria: Results of the Research University Network Thailand Study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0067521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karnmongkol, C.; Wiriyaampaiwong, P.; Teerakul, M.; Treeinthong, J.; Srisamoot, N.; Tankrathok, A. Emergence of NDM-1-producing Raoultella ornithinolytica from reservoir water in Northeast Thailand. Vet. World 2023, 16, 2321–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Amarasiri, M.; Takezawa, T.; Malla, B.; Furukawa, T.; Sherchand, J.B.; Haramoto, E.; Sei, K. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes in drinking and environmental water sources of the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 894014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ding, H.; Qiao, M.; Zhong, J.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, C.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, P.; Han, L.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Y.; et al. Characterization of antibiotic resistance genes and bacterial community in selected municipal and industrial sewage treatment plants beside Poyang Lake. Water Res. 2020, 174, 115603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Yang, H.; Xu, X. Effects of Water Pollution on Human Health and Disease Heterogeneity: A Review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 880246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assawatheptawee, K.; Sowanna, N.; Treebupachatsakul, P.; Na-udom, A.; Luangtongkum, T.; Niumsup, P.R. Presence and characterization of blaNDM-1-positive carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from outpatients in Thailand. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2023, 56, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laolerd, W.; Akeda, Y.; Preeyanon, L.; Ratthawongjirakul, P.; Santanirand, P. Carbapenemase-Producing Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae from Bangkok, Thailand, and Their Detection by the Carba NP and Modified Carbapenem Inactivation Method Tests. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paveenkittiporn, W.; Lyman, M.; Biedron, C.; Chea, N.; Bunthi, C.; Kolwaite, A.; Janejai, N. Molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales in Thailand, 2016–2018. Antimicrob Resist. Infect Control. 2021, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Songsaeng, W.; Prapasarakul, N.; Wongsurawat, T.; Sirichokchatchawan, W. The occurrence and genomic characteristics of the blaIMI-1 carbapenemase-producing Enterobacter cloacae complex retrieved from natural water sources in central Thailand. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxad229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abril, D.; Vergara, E.; Palacios, D.; Leal, A.L.; Marquez-Ortiz, R.A.; Madronero, J.; Corredor Rozo, Z.L.; De La Rosa, Z.; Nieto, C.A.; Vanegas, N.; et al. Within patient genetic diversity of bla(KPC) harboring Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Colombian hospital and identification of a new NTE(KPC) platform. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lu, B.; Lin, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yan, H.; Qu, M.; Jia, L.; Wang, Q. Molecular Characteristics of Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates From Outpatients in Sentinel Hospitals, Beijing, China, 2010–2019. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Singh, A.K.; Kaur, R.; Verma, S.; Singh, S. Antimicrobials and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Water Bodies: Pollution, Risk, and Control. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 830861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Jia, X.; Liu, H.; Li, S.; Wu, X.; Huang, S. Emergence of NDM-5-Producing Escherichia coli in a Teaching Hospital in Chongqing, China: IncF-Type Plasmids May Contribute to the Prevalence of bla (NDM-) (5). Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zou, H.; Jia, X.; He, X.; Su, Y.; Zhou, L.; Shen, Y.; Sheng, C.; Liao, A.; Li, C.; Li, Q. Emerging Threat of Multidrug Resistant Pathogens From Neonatal Sepsis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 694093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ogura, Y.; Ooka, T.; Iguchi, A.; Toh, H.; Asadulghani, M.; Oshima, K.; Kodama, T.; Abe, H.; Nakayama, K.; Kurokawa, K.; et al. Comparative genomics reveal the mechanism of the parallel evolution of O157 and non-O157 enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 17939–17944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Duggett, N.A.; Randall, L.P.; Horton, R.A.; Lemma, F.; Kirchner, M.; Nunez-Garcia, J.; Brena, C.; Williamson, S.M.; Teale, C.; Anjum, M.F. Molecular epidemiology of isolates with multiple mcr plasmids from a pig farm in Great Britain: The effects of colistin withdrawal in the short and long term. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 3025–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.Y.; Chen, J.W.; Liu, T.L.; Yan, J.J.; Wu, J.J. Comparative Genomics of Escherichia coli Sequence Type 219 Clones From the Same Patient: Evolution of the IncI1 blaCMY-Carrying Plasmid in Vivo. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carattoli, A.; Villa, L.; Poirel, L.; Bonnin, R.A.; Nordmann, P. Evolution of IncA/C blaCMY-₂-carrying plasmids by acquisition of the blaNDM-₁ carbapenemase gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Partridge, S.R.; Kwong, S.M.; Firth, N.; Jensen, S.O. Mobile Genetic Elements Associated with Antimicrobial Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 31, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Villa, L.; Capone, A.; Fortini, D.; Dolejska, M.; Rodríguez, I.; Taglietti, F.; De Paolis, P.; Petrosillo, N.; Carattoli, A. Reversion to susceptibility of a carbapenem-resistant clinical isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing KPC-3. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 2482–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lei, C.-W.; Chen, X.; Yao, T.-G.; Yu, J.-W.; Hu, W.-L.; Mao, X.; Wang, H.-N. Characterization of IncC Plasmids in Enterobacterales of Food-Producing Animals Originating From China. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 580960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, J.A.; Kloos, J.; Johnsen, P.J.; Samuelsen, Ø. Host dependent maintenance of a blaNDM-1-encoding plasmid in clinical Escherichia coli isolates. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleichenbacher, S.; Stevens, M.J.A.; Zurfluh, K.; Perreten, V.; Endimiani, A.; Stephan, R.; Nuesch-Inderbinen, M. Environmental dissemination of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in rivers in Switzerland. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 115081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samreen; Ahmad, I.; Malak, H.A.; Abulreesh, H.H. Environmental antimicrobial resistance and its drivers: A potential threat to public health. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 27, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suay-García, B.; Pérez-Gracia, M.T. Present and Future of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) Infections. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tekele, S.G.; Teklu, D.S.; Legese, M.H.; Weldehana, D.G.; Belete, M.A.; Tullu, K.D.; Birru, S.K. Multidrug-Resistant and Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9999638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rose, R.; Nolan, D.J.; Ashcraft, D.; Feehan, A.K.; Velez-Climent, L.; Huston, C.; Lain, B.; Rosenthal, S.; Miele, L.; Fogel, G.B. Comparing antimicrobial resistant genes and phenotypes across multiple sequencing platforms and assays for Enterobacterales clinical isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hafi, B.; Rasheed, S.S.; Abou Fayad, A.G.; Araj, G.F.; Matar, G.M. Evaluating the efficacies of carbapenem/β-lactamase inhibitors against carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria in vitro and in vivo. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Beltrán, J.; DelaFuente, J.; León-Sampedro, R.; MacLean, R.C.; San Millán, Á. Beyond horizontal gene transfer: The role of plasmids in bacterial evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, Y.; Nazareno, P.J.; Nakano, R.; Mondoy, M.; Nakano, A.; Bugayong, M.P.; Bilar, J.; Perez, M.t.; Medina, E.J.; Saito-Obata, M.; et al. Environmental Presence and Genetic Characteristics of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae from Hospital Sewage and River Water in the Philippines. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e01906-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marquez-Ortiz, R.A.; Haggerty, L.; Olarte, N.; Duarte, C.; Garza-Ramos, U.; Silva-Sanchez, J.; Castro, B.E.; Sim, E.M.; Beltran, M.; Moncada, M.V.; et al. Genomic Epidemiology of NDM-1-Encoding Plasmids in Latin American Clinical Isolates Reveals Insights into the Evolution of Multidrug Resistance. Genome Biol. Evol. 2017, 9, 1725–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zurfluh, K.; Hächler, H.; Nüesch-Inderbinen, M.; Stephan, R. Characteristics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae Isolates from rivers and lakes in Switzerland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 3021–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 34th ed.; Clinical Lab Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024; p. 416. [Google Scholar]

- Poirel, L.; Walsh, T.R.; Cuvillier, V.; Nordmann, P. Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemase genes. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 70, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Tang, B.; Zheng, X.; Chang, J.; Ma, J.; He, Y.; Yang, H.; Wu, Y. Emergence of Incl2 plasmid-mediated colistin resistance in avian Escherichia fergusonii. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2022, 369, fnac016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhu, J.; Gong, D.; Wu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, L. Whole genome sequence of EC16, a blaNDM-5-, blaCTX-M-55-, and fosA3-coproducing Escherichia coli ST167 clinical isolate from China. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 29, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikhan, N.; Petty, N.; Zakour, N.; Beatson, S. BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): Simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genom. 2011, 12, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.; Petty, N.; Scott, B. Easyfig: A genome comparison visualiser. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Isolate No. | Bacteria Species | Location of Water Sources | Carbapenems | Other Antimicrobials | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOR | IPM | MEM | ETP | AMK | AMC | AMP | FEP | FOX | CAZ | CTX | SAM | TZP | CST | CIP | CRO | LVX | GEN | NET | SXT | |||

| WS_5-3 | Escherichia coli | Next to pig farms | R | I | R | R | S | R | I | R | I | R | R | R | I | S | I | R | R | I | S | R |

| WS_29-1 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Within community | R | I | R | R | S | R | I | R | S | R | R | R | I | R | S | R | S | I | S | R |

| Isolate | Bacterial Species | Carbapenemase Genes | Other AMR Genes a | Gene Location (Replicon Type) | Transfer Ability Rate | ST | GenBank Accession * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

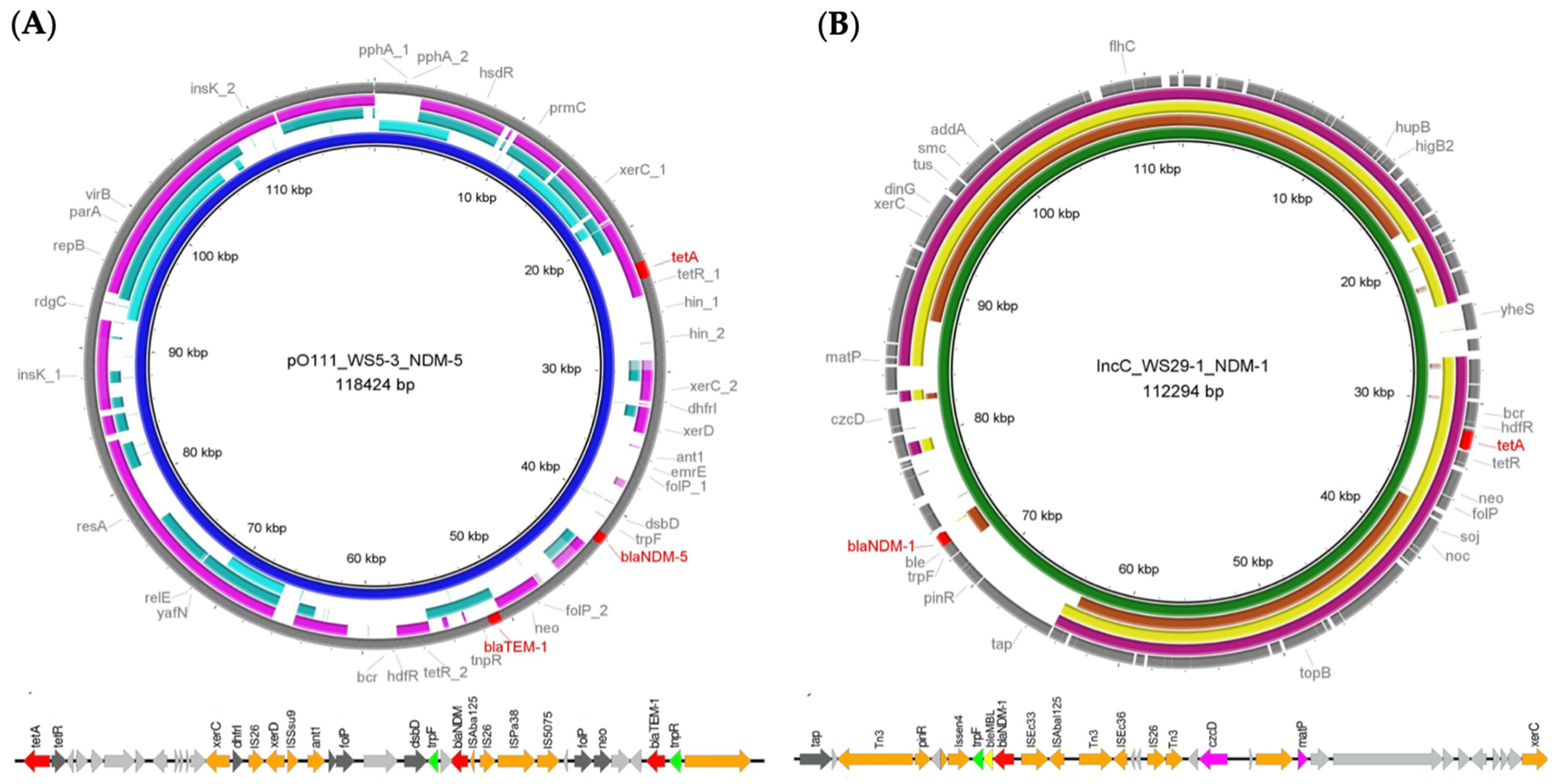

| WS5-3 | Escherichia coli | blaNDM-5 | aph(6)-Id, aadA2, aph(3″)-Ib, dfrA14, sul2, sul1, dfrA12, qnrS1, tet(A), blaTEM-1 | Plasmid (pO111) | 2.24 × 10−4 | ST 4538 | CP110512 |

| WS29-1 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | blaNDM-1 | aph (3″)-lb, mph(A), aph(6)-ld, sul2, tet(A), blaSHV | Plasmid (IncC) | 5.52 × 10−3 | ST 6316 b | CP110518 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Songsaeng, W.; Kurilung, A.; Prapasarakul, N.; Wongsurawat, T.; Am-In, N.; Lugsomya, K.; Lohwacharin, J.; Damrongsiri, S.; Shein, H.Z.; Sirichokchatchawan, W. The Emergence of blaNDM-Encoding Plasmids in Enterobacteriaceae Isolated from Shared Water Resources for Livestock and Human Utilization in Central Thailand. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010008

Songsaeng W, Kurilung A, Prapasarakul N, Wongsurawat T, Am-In N, Lugsomya K, Lohwacharin J, Damrongsiri S, Shein HZ, Sirichokchatchawan W. The Emergence of blaNDM-Encoding Plasmids in Enterobacteriaceae Isolated from Shared Water Resources for Livestock and Human Utilization in Central Thailand. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleSongsaeng, Wipawee, Alongkorn Kurilung, Nuvee Prapasarakul, Thidathip Wongsurawat, Nutthee Am-In, Kittitat Lugsomya, Jenyuk Lohwacharin, Seelawut Damrongsiri, Htet Zaw Shein, and Wandee Sirichokchatchawan. 2026. "The Emergence of blaNDM-Encoding Plasmids in Enterobacteriaceae Isolated from Shared Water Resources for Livestock and Human Utilization in Central Thailand" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010008

APA StyleSongsaeng, W., Kurilung, A., Prapasarakul, N., Wongsurawat, T., Am-In, N., Lugsomya, K., Lohwacharin, J., Damrongsiri, S., Shein, H. Z., & Sirichokchatchawan, W. (2026). The Emergence of blaNDM-Encoding Plasmids in Enterobacteriaceae Isolated from Shared Water Resources for Livestock and Human Utilization in Central Thailand. Antibiotics, 15(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010008