Cathelicidin-like Peptide for Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Peptide Synthesis

3.2. Microorganisms

3.3. Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Assays

3.4. Minimal Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) Assays

3.5. Minimal Inhibitory Concentration of Biofilms (MBIC) Assays

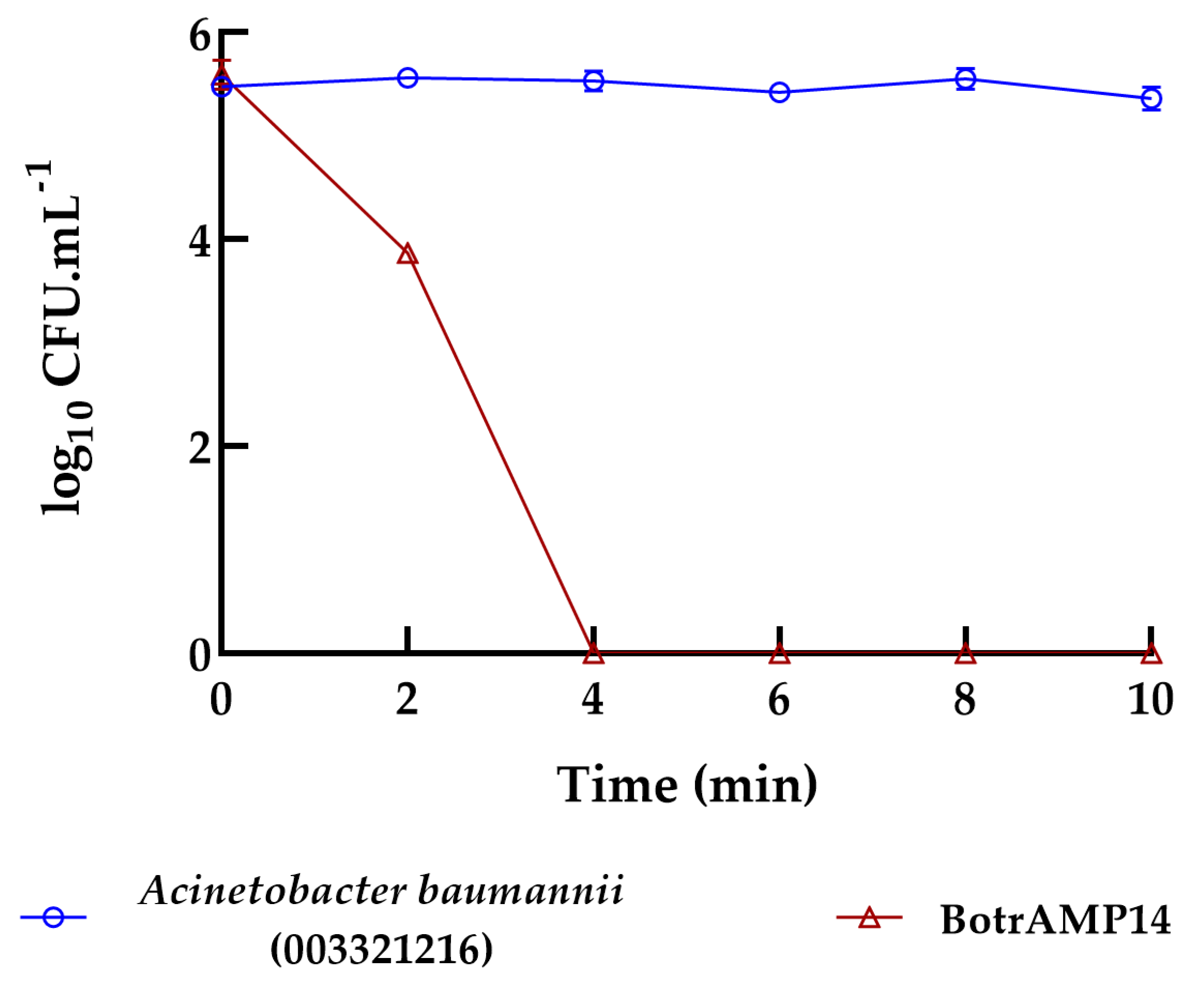

3.6. Bacterial Killing Experiments

3.7. Cytotoxicity Assay

3.8. Hemolytic Assay

3.9. Skin Wound Infection Mouse Model

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMP | Antimicrobial Peptides |

| Btn (15–34) | Bothrops cathelicidin 15 |

| BotrAMP14 | Bothrops cathelicidin analogue 14 |

| Ctn (15–34) | Crotalus cathelicidin 15 |

| CrotAMP14 | Crotalus cathelicidin 14 |

| MIC | Minimal Inhibitory Concentration |

| MICB | Minimal Inhibitory Concentration of Biofilm |

| MBC | Minimal Bactericidal Concentration |

| MBEC | Minimal Biofilm Eradication Concentration |

| CFU | Colonies Forming Units |

| IC50 | Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration |

| DP | drop plate |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay |

| F-moc | solid phase chemical peptide synthesis |

| HPLC | High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| KpC+ | Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase positive |

| MHA | Muller-Hinton agar |

| MHB | Muller-Hinton broth |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| CEUA | Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee |

| UCDB | Universidade Católica Dom Bosco |

References

- Maslova, E.; Eisaiankhongi, L.; Sjöberg, F.; McCarthy, R.R. Burns and Biofilms: Priority Pathogens and in Vivo Models. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Li, Y.; Wu, M.X. Bacteria-Specific pro-Photosensitizer Kills Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sati, H.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Hansen, P.; Garlasco, J.; Campagnaro, E.; Boccia, S.; Castillo-Polo, J.A.; Magrini, E.; Garcia-Vello, P.; et al. The WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024: A Prioritisation Study to Guide Research, Development, and Public Health Strategies against Antimicrobial Resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawani, M.; Fauzi, M.B. Injectable Hydrogels for Chronic Skin Wound Management: A Concise Review. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, B.R.; Hwang, C.; Talbot, S.; Hibler, B.; Matoori, S.; Mooney, D.J. Breakthrough Treatments for Accelerated Wound Healing. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade7007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, J.S.; Madden, L.; Chew, S.Y.; Becker, D.L. Drug Therapies and Delivery Mechanisms to Treat Perturbed Skin Wound Healing. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019, 149–150, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.R.; Bernstein, J.M. Chronic Wound Infection: Facts and Controversies. Clin. Dermatol. 2010, 28, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Liang, H.; Clarke, E.; Jackson, C.; Xue, M. Inflammation in Chronic Wounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, D.D.; Wolcott, R.D.; Percival, S.L. Biofilms in Wounds: Management Strategies. J. Wound Care 2008, 17, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.; Simões, S.; Ascenso, A.; Reis, C.P. Therapeutic Advances in Wound Healing. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2022, 33, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, P.; Wächter, J.; Windbergs, M. Therapy of Infected Wounds: Overcoming Clinical Challenges by Advanced Drug Delivery Systems. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2021, 11, 1545–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhirajan, N.; Shanmugasundaram, N.; Shanmuganathan, S.; Babu, M. Collagen-Based Wound Dressing for Doxycycline Delivery: In-Vivo Evaluation in an Infected Excisional Wound Model in Rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2009, 61, 1617–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corduas, F.; Lamprou, D.A.; Mancuso, E. Next-Generation Surgical Meshes for Drug Delivery and Tissue Engineering Applications: Materials, Design and Emerging Manufacturing Technologies. Bio-Des. Manuf. 2021, 4, 278–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, M.; Shamloo, A.; Aghababaei, Z.; Vossoughi, M.; Moravvej, H. Antimicrobial Wound Dressing Containing Silver Sulfadiazine with High Biocompatibility: In Vitro Study. Artif. Organs 2016, 40, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, J.; Zhang, R.; Min, H.; Huang, M. Development of Silver Sulfadiazine Loaded Bacterial Cellulose/Sodium Alginate Composite Films with Enhanced Antibacterial Property. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 132, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiadis, J.; Nascimento, V.B.; Donat, C.; Okereke, I.; Shoja, M.M. Dakin’s Solution: One of the Most Important and Far-Reaching Contributions to the Armamentarium of the Surgeons. Burns 2019, 45, 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.; Pastar, I.; Houghten, R.A.; Padhee, S.; Higa, A.; Solis, M.; Valdez, J.; Head, C.R.; Michaels, H.; Lenhart, B.; et al. Novel Cyclic Lipopeptides Fusaricidin Analogs for Treating Wound Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 708904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, S. Mepilex Ag: An Antimicrobial, Absorbent Foam Dressing with Safetac Technology. Br. J. Nurs. 2009, 18, S30–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockmann, A.; Schill, T.; Hartmann, F.; Grönemeyer, L.-L.; Holzkamp, R.; Schön, M.P.; Thoms, K.-M. Testing Elevated Protease Activity: Prospective Analysis of 160 Wounds. Adv. Skin Wound Care 2018, 31, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyszczyk, P.; Schloss, R.; Palmer, A.; Berthiaume, F. The Role of Macrophages in Acute and Chronic Wound Healing and Interventions to Promote Pro-Wound Healing Phenotypes. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Sinha, M.; Datta, S.; Abas, M.; Chaffee, S.; Sen, C.K.; Roy, S. Monocyte and Macrophage Plasticity in Tissue Repair and Regeneration. Am. J. Pathol. 2015, 185, 2596–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesketh, M.; Sahin, K.B.; West, Z.E.; Murray, R.Z. Macrophage Phenotypes Regulate Scar Formation and Chronic Wound Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, N.G.J.; Cardoso, M.H.; Velikova, N.; Giesbers, M.; Wells, J.M.; Rezende, T.M.B.; de Vries, R.; Franco, O.L. Physicochemical-Guided Design of Cathelicidin-Derived Peptides Generates Membrane Active Variants with Therapeutic Potential. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Júnior, N.G.; Freire, M.S.; Almeida, J.A.; Rezende, T.M.B.; Franco, O.L. Antimicrobial and Proinflammatory Effects of Two Vipericidins. Cytokine 2018, 111, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcao, C.B.; de La Torre, B.G.; Pérez-Peinado, C.; Barron, A.E.; Andreu, D.; Rádis-Baptista, G. Vipericidins: A Novel Family of Cathelicidin-Related Peptides from the Venom Gland of South American Pit Vipers. Amino Acids 2014, 46, 2561–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Lan, X.-Q.; Du, Y.; Chen, P.-Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, F.; Lee, W.-H.; Zhang, Y. King Cobra Peptide OH-CATH30 as a Potential Candidate Drug through Clinic Drug-Resistant Isolates. Zool. Res. 2018, 39, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcao, C.B.; Pérez-Peinado, C.; de la Torre, B.G.; Mayol, X.; Zamora-Carreras, H.; Jiménez, M.Á.; Rádis-Baptista, G.; Andreu, D. Structural Dissection of Crotalicidin, a Rattlesnake Venom Cathelicidin, Retrieves a Fragment with Antimicrobial and Antitumor Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 8553–8563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, R.P.; da Hora, G.C.A.; Ramstedt, M.; Soares, T.A. Outer Membrane Remodeling: The Structural Dynamics and Electrostatics of Rough Lipopolysaccharide Chemotypes. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014, 10, 2488–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Peinado, C.; Dias, S.A.; Domingues, M.M.; Benfield, A.H.; Freire, J.M.; Rádis-Baptista, G.; Gaspar, D.; Castanho, M.A.R.B.; Craik, D.J.; Henriques, S.T.; et al. Mechanisms of Bacterial Membrane Permeabilization by Crotalicidin (Ctn) and Its Fragment Ctn(15-34), Antimicrobial Peptides from Rattlesnake Venom. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 1536–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Gao, J.; Zhang, S.; Wu, S.; Xie, Z.; Ling, G.; Kuang, Y.-Q.; Yang, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y. Identification and Characterization of the First Cathelicidin from Sea Snakes with Potent Antimicrobial and Anti-Inflammatory Activity and Special Mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 16633–16652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, G.; Eriksson, J.; Terry, A.; Edwards, K.; Lawrence, M.J.; Barlow, D.; Harvey, R.D. Characterization of the Aggregates Formed by Various Bacterial Lipopolysaccharides in Solution and upon Interaction with Antimicrobial Peptides. Langmuir 2015, 31, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.E.S.; Pol-Fachin, L.; Lins, R.D.; Soares, T.A. Polymyxin Binding to the Bacterial Outer Membrane Reveals Cation Displacement and Increasing Membrane Curvature in Susceptible but Not in Resistant Lipopolysaccharide Chemotypes. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 2181–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.H.; Fuente-Nunez, C.d.l.; Santos, N.C.; Zasloff, M.A.; Franco, O.L. Influence of Antimicrobial Peptides on the Bacterial Membrane Curvature and Vice Versa. Trends Microbiol. 2024, 32, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, M.H.; Chan, L.Y.; Cândido, E.S.; Buccini, D.F.; Rezende, S.B.; Torres, M.D.T.; Oshiro, K.G.N.; Silva, Í.C.; Gonçalves, S.; Lu, T.K.; et al. An N-Capping Asparagine–Lysine–Proline (NKP) Motif Contributes to a Hybrid Flexible/Stable Multifunctional Peptide Scaffold. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 9410–9424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Weide, H.; Brunetti, J.; Pini, A.; Bracci, L.; Ambrosini, C.; Lupetti, P.; Paccagnini, E.; Gentile, M.; Bernini, A.; Niccolai, N.; et al. Investigations into the Killing Activity of an Antimicrobial Peptide Active against Extensively Antibiotic-Resistant K. Pneumon Iae and P. Aeruginosa. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2017, 1859, 1796–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, R.M.; Monges, B.E.D.; Oshiro, K.G.N.; Cândido, E.d.S.; Pimentel, J.P.F.; Franco, O.L.; Cardoso, M.H. Advantages and Challenges of Using Antimicrobial Peptides in Synergism with Antibiotics for Treating Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. ACS Infect. Dis. 2025, 11, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, L.; Gross, S.P.; Siryaporn, A. Developing Antimicrobial Synergy with AMPs. Front. Med. Technol. 2021, 3, 640981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzolato-Cezar, L.R.; Okuda-Shinagawa, N.M.; Machini, M.T. Combinatory Therapy Antimicrobial Peptide-Antibiotic to Minimize the Ongoing Rise of Resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiegand, I.; Hilpert, K.; Hancock, R.E.W. Agar and Broth Dilution Methods to Determine the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of Antimicrobial Substances. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, R.M.; Ambler, J.; Mitchell, S.L.; Castanheira, M.; Dingle, T.; Hindler, J.A.; Koeth, L.; Sei, K. The CLSI Methods Development and Standardization Working Group of the Subcommittee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. CLSI Methods Development and Standardization Working Group Best Practices for Evaluation of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e01934-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente-Núñez, C.; Hancock, R.E.W. Using Anti-Biofilm Peptides to Treat Antibiotic-Resistant Bacterial Infections. Postdr. J. 2015, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendi, P.; Ruppen, C. Time Kill Assays for Streptococcus agalactiae and Synergy Testing. Protoc. Exch. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irazazabal, L.N.; Porto, W.F.; Ribeiro, S.M.; Casale, S.; Humblot, V.; Ladram, A.; Franco, O.L. Selective Amino Acid Substitution Reduces Cytotoxicity of the Antimicrobial Peptide Mastoparan. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1858, 2699–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W.; Liao, C.Z.; Wong, H.M.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Tjong, S.C. Preparation of Polyetheretherketone Composites with Nanohydroxyapatite Rods and Carbon Nanofibers Having High Strength, Good Biocompatibility and Excellent Thermal Stability. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 19417–19429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccini, D.F.; Nunes, A.A.; Silva, G.G.; Silva, O.N.; Franco, O.L.; Moreno, S.E. Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities of Rhipicephalus microplus saliva. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2018, 8, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.H.; Cândido, E.S.; Chan, L.Y.; Der Torossian Torres, M.; Oshiro, K.G.N.; Rezende, S.B.; Porto, W.F.; Lu, T.K.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C.; Craik, D.J.; et al. A Computationally Designed Peptide Derived from Escherichia Coli as a Potential Drug Template for Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Therapies. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Antibacterial Activity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microorganism | MIC (MBC) [µM] | |||

| Btn (15–34) | BotrAMP14 | Ctn (15–34) | CrotAMP14 | |

| A. baumannii 003321216 | 12.5 (25) | 1.56 (1.56) | 3.12 (6.25) | 1.56 (1.56) |

| E. coli KpC+ 001812446 | 6.25 (6.25) | 1.56 (1.56) | 6.25 (6.25) | 3.12 (3.12) |

| P. aeruginosa 003321199 | 6.25 (6.25) | 0.78 (0.78) | 3.12 (3.12) | 1.56 (1.56) |

| Antibiofilm Activity (MBIC) | ||||

| A. baumannii 003321216 | 12.5 | 1.56 | 12.5 | 3.12 |

| E. coli KpC+ 001812446 | 12.5 | 1.56 | 6.25 | 1.56 |

| Hemolytic activity [µM] | ||||

| Murine erythrocytes | >128 | 128 | >128 | >128 |

| Cytotoxic activity (IC50) | ||||

| Raw 264.7 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cândido, E.d.S.; Buccini, D.F.; Miranda, E.d.B.; Gonçalves, R.M.; Brandão, A.L.d.O.; Nieto-Marín, V.; Leal, A.P.F.; Rezende, S.B.; Cardoso, M.H.; Franco, O.L. Cathelicidin-like Peptide for Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Control. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010077

Cândido EdS, Buccini DF, Miranda EdB, Gonçalves RM, Brandão ALdO, Nieto-Marín V, Leal APF, Rezende SB, Cardoso MH, Franco OL. Cathelicidin-like Peptide for Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Control. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010077

Chicago/Turabian StyleCândido, Elizabete de Souza, Danieli Fernanda Buccini, Elizangela de Barros Miranda, Regina Meneses Gonçalves, Amanda Loren de Oliveira Brandão, Valentina Nieto-Marín, Ana Paula Ferreira Leal, Samilla Beatriz Rezende, Marlon Henrique Cardoso, and Octavio Luiz Franco. 2026. "Cathelicidin-like Peptide for Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Control" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010077

APA StyleCândido, E. d. S., Buccini, D. F., Miranda, E. d. B., Gonçalves, R. M., Brandão, A. L. d. O., Nieto-Marín, V., Leal, A. P. F., Rezende, S. B., Cardoso, M. H., & Franco, O. L. (2026). Cathelicidin-like Peptide for Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Control. Antibiotics, 15(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010077