Activity of Natural Substances and n-Undecyl-α/β-l-Fucopyranoside Against the Formation of Pathogenic Biofilms by Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Chemical Synthesis of n-Undecyl-α/β-l-Fucopyranoside

2.2. MIC Values

2.3. Dependence of Biofilm Formation on the Culture Medium

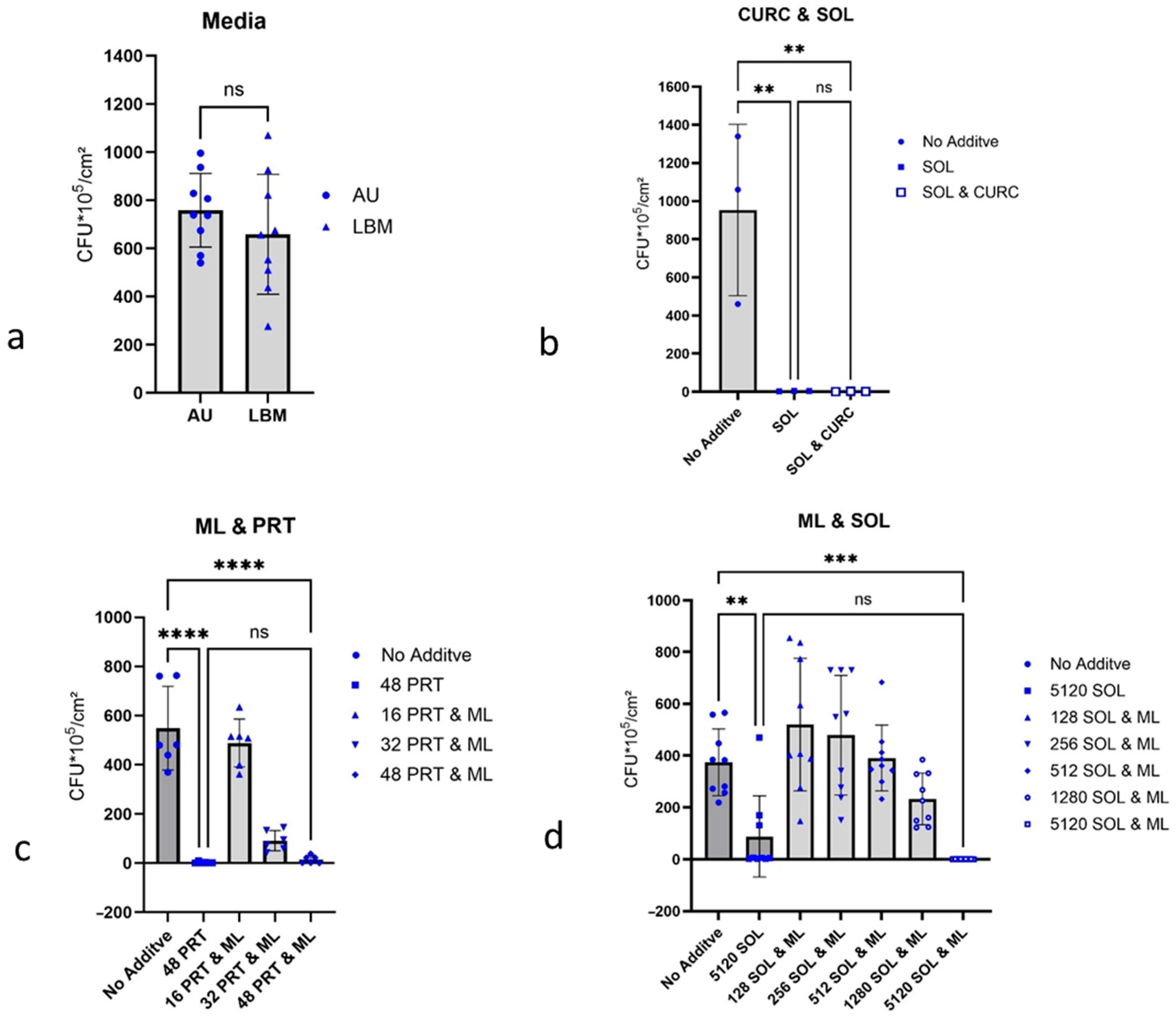

2.4. Growth Inhibition of P. aeruginosa Biofilms

2.4.1. Curcumin and 1-Monolaurin, Each with Detergent

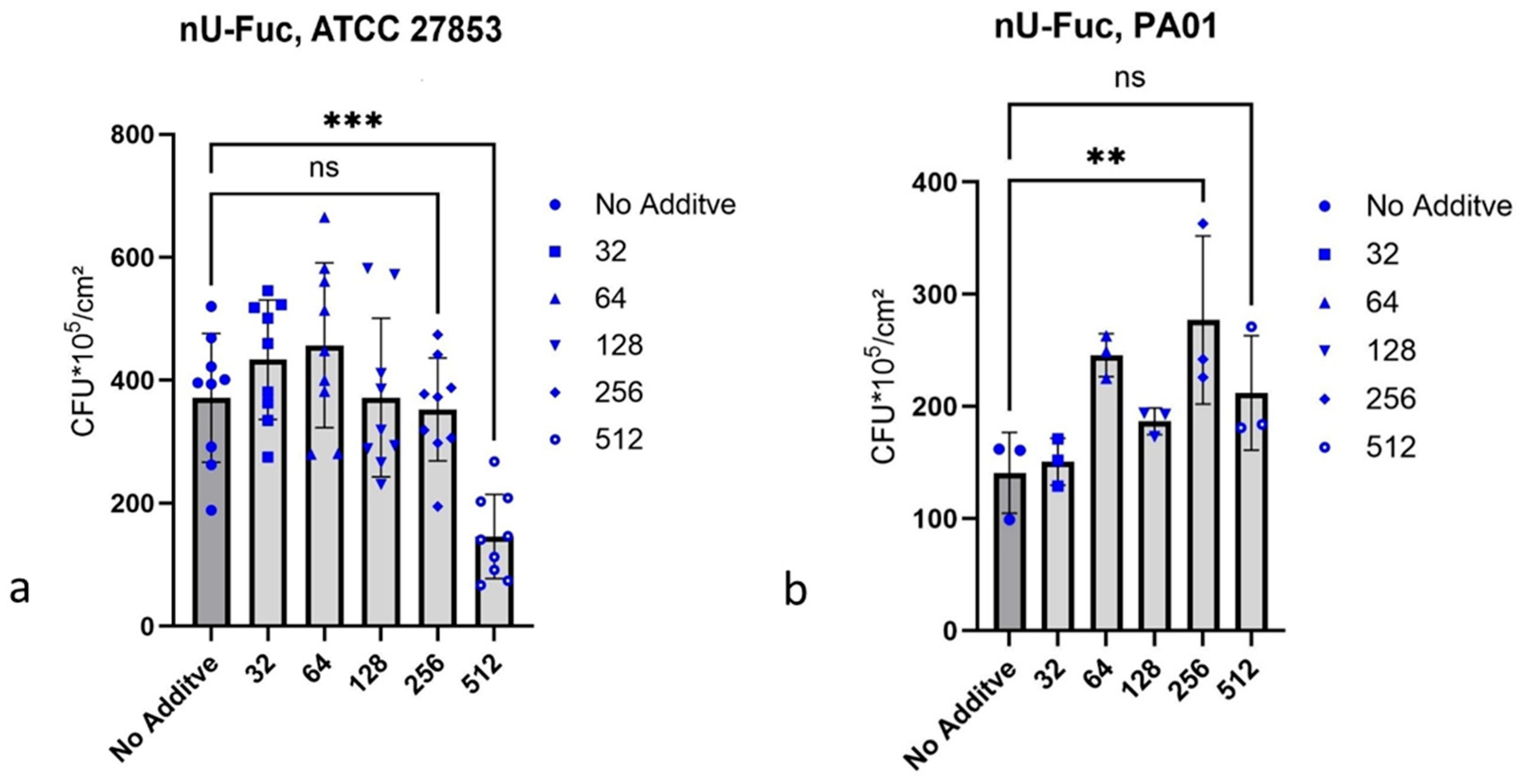

2.4.2. n-Undecyl-α/β-l-Fucopyranoside

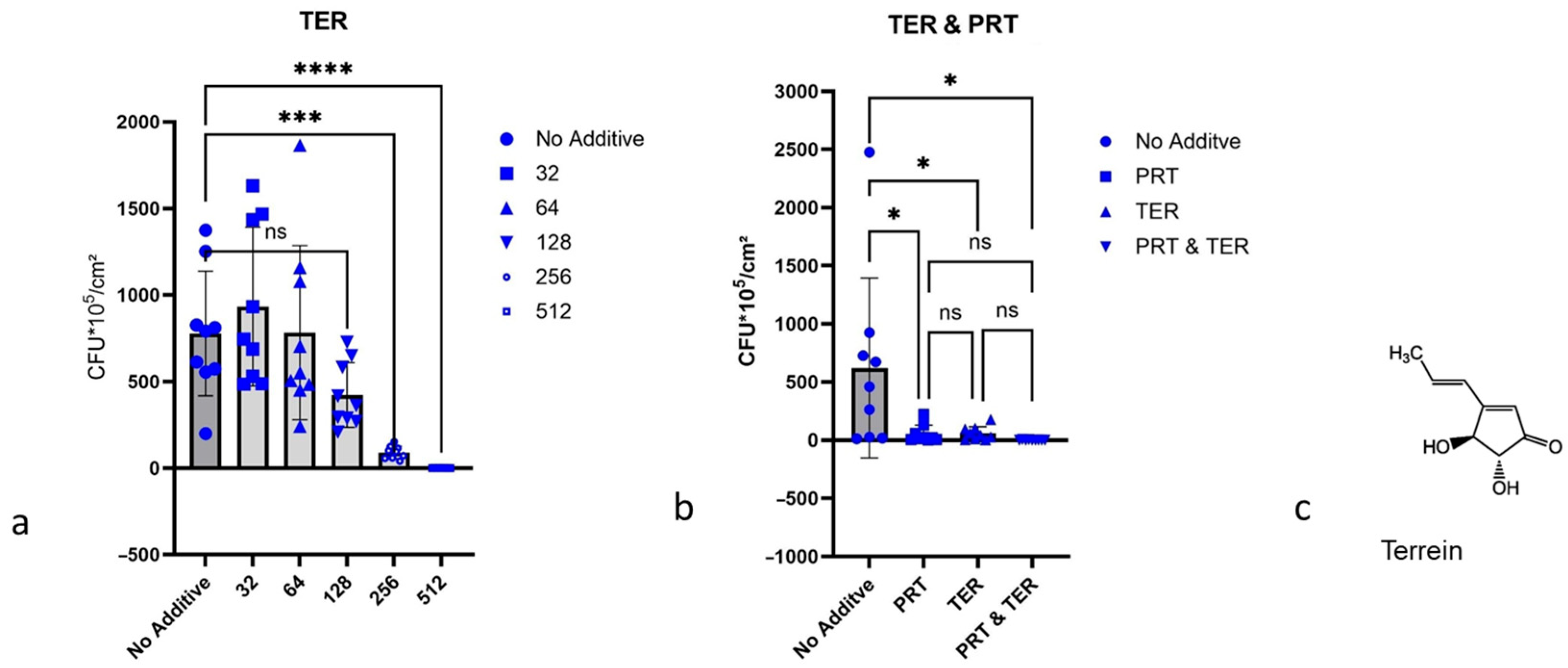

2.4.3. Terrein

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Substances and Devices

4.1.1. Culture Media

4.1.2. Chemicals and Supporting Material

4.1.3. Devices

4.2. Organisms

4.3. Culture Conditions

4.3.1. Primary Culture

4.3.2. Secondary Culture

4.4. Chemical Synthesis of n-Undecyl-α/β-l-Fucopyranoside

4.5. Determination of Minimal Inhibitory Concentration

4.6. Catheter Biofilm Experiments

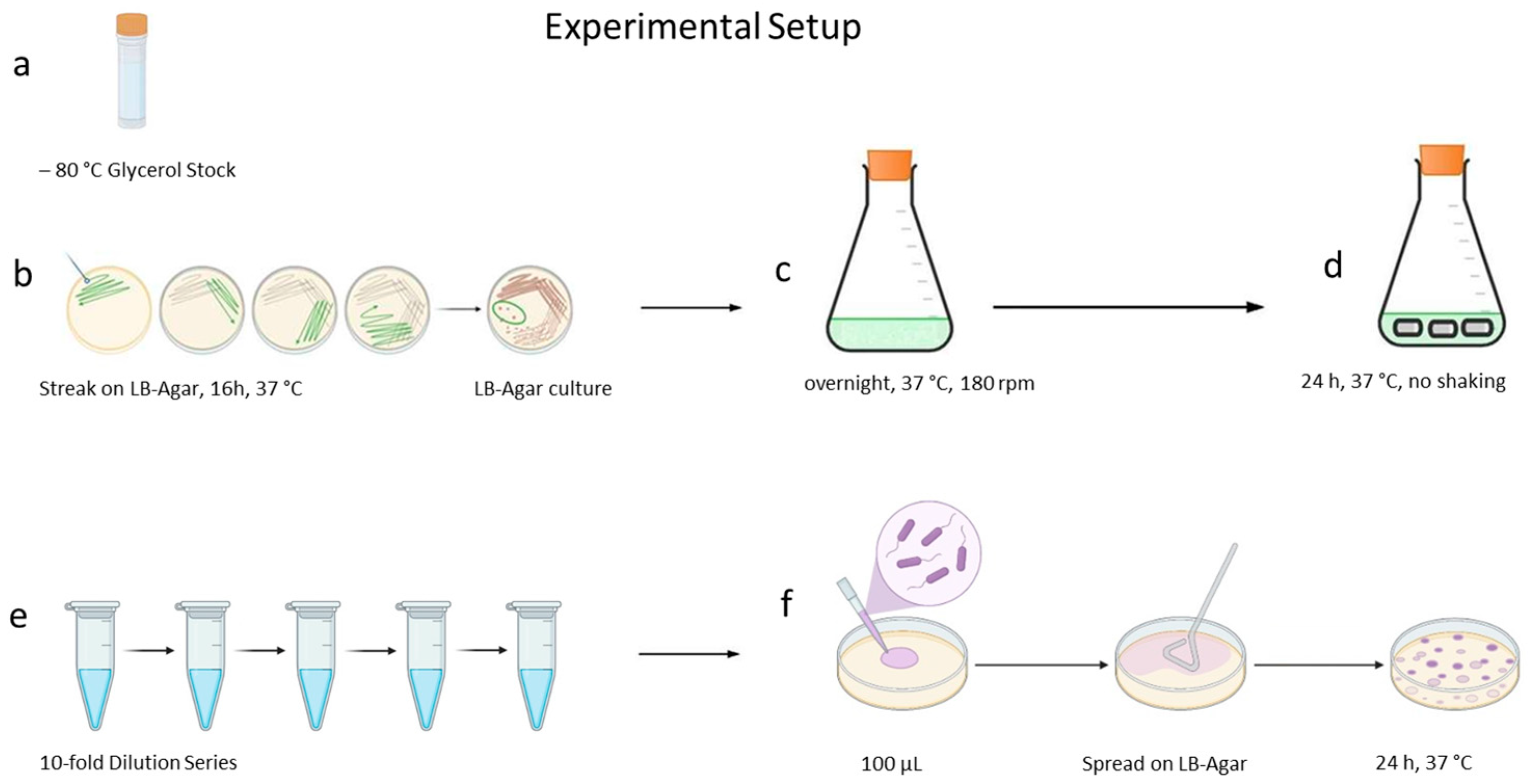

4.6.1. General Procedure Catheter Experiment

4.6.2. Influence of the Culture Medium

4.6.3. Curcumin and 1-Monolaurin, Each in Combination with Soluplus®

4.6.4. n-Undecyl-α/β-l-Fucopyranoside

4.6.5. Terrein

4.7. Estimation of Colony-Forming Units in the Biofilm

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATCC | American Type Cell Collection |

| AU | Artificial Urine |

| c-di GMP | Cyclic di-Guanosine Monophosphate |

| CFU | Colony-Forming Unit |

| CURC | Curcumin |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| DSMZ | Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (= German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures) |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| HRMS | High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry |

| Hz | Hertz |

| LBM | Lysogeny Broth Medium |

| M+ | Molecular Ion Peak |

| ML | 1-Monolaurin |

| MW | Molecular Weight |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| nU-Fuc | n-Undecyl-α/β-l-Fucopyranoside |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PIP | Piperacillin |

| ppm | Part per Million |

| rpm | Revolutions per Minute |

| PRT | Prontosan® |

| QC | Quality Control |

| SOL | Soluplus® |

| TER | Terrein |

| TSB | Tryptone Soy Broth |

References

- Li, X.; Gu, N.; Huang, T.Y.; Zhong, F.; Peng, G. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A typical biofilm forming pathogen and an emerging but underestimated pathogen in food processing. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1114199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Lai, Y.; Bougouffa, S.; Xu, Z.; Yan, A. Comparative genome and transcriptome analysis reveals distinctive surface characteristics and unique physiological potentials of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, P.; Locklin, J.; Handa, H. A review of the recent advances in antimicrobial coatings for urinary catheters. Acta Biomater. 2017, 50, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, J.; Schmidt, S.; Wagenlehner, F.; Schneidewind, L. Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections in Adult Patients. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2020, 117, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Yuan, X. Antimicrobial strategies for urinary catheters. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2019, 107, 445–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasamiravaka, T.; Labtani, Q.; Duez, P.; El Jaziri, M. The formation of biofilms by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A review of the natural and synthetic compounds interfering with control mechanisms. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 759348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, F.Y.; Darcan, C.; Kariptaş, E. The Determination, Monitoring, Molecular Mechanisms and Formation of Biofilm in E. coli. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauer, K.; Camper, A.K.; Ehrlich, G.D.; Costerton, J.W.; Davies, D.G. Pseudomonas aeruginosa displays multiple phenotypes during development as a biofilm. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 1140–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laventie, B.-J.; Sangermani, M.; Estermann, F.; Manfredi, P.; Planes, R.; Hug, I.; Jaeger, T.; Meunier, E.; Broz, P.; Jenal, U. A Surface-Induced Asymmetric Program Promotes Tissue Colonization by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 140–152.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagge, N.; Hentzer, M.; Andersen, J.B.; Ciofu, O.; Givskov, M.; Høiby, N. Dynamics and spatial distribution of beta-lactamase expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 1168–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjarnsholt, T. The role of bacterial biofilms in chronic infections. APMIS Suppl. 2013, 136, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, L.R.; D’Argenio, D.A.; MacCoss, M.J.; Zhang, Z.; Jones, R.A.; Miller, S.I. Aminoglycoside antibiotics induce bacterial biofilm formation. Nature 2005, 436, 1171–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardung, H.; Djuric, D.; Ali, S. Combining HME & Solubilization: Soluplus®—The Solid Solution. Drug Deliv. Technol. 2010, 10, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Baik, S.; Lau, J.; Huser, V.; McDonald, C.J. Association between tendon ruptures and use of fluoroquinolone, and other oral antibiotics: A 10-year retrospective study of 1 million US senior Medicare beneficiaries. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Li, H.; Johnson, A.; Karasawa, T.; Zhang, Y.; Meier, W.B.; Taghizadeh, F.; Kachelmeier, A.; Steyger, P.S. Inflammation up-regulates cochlear expression of TRPV1 to potentiate drug-induced hearing loss. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, H.W.; Talbot, G.H.; Bradley, J.S.; Edwards, J.E.; Gilbert, D.; Rice, L.B.; Scheld, M.; Spellberg, B.; Bartlett, J. Bad bugs, no drugs: No ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandegren, L. Selection of antibiotic resistance at very low antibiotic concentrations. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2014, 119, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlaes, D.M.; Sahm, D.; Opiela, C.; Spellberg, B. The FDA reboot of antibiotic development. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 4605–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loose, M.; Pilger, E.; Wagenlehner, F. Anti-Bacterial Effects of Essential Oils against Uropathogenic Bacteria. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Xiao, L.; Qin, W.; Loy, D.A.; Wu, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Q. Preparation, characterization and antioxidant properties of curcumin encapsulated chitosan/lignosulfonate micelles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 281, 119080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, T.; Li, T.; Wang, Z.; Li, J. Curcumin liposomes interfere with quorum sensing system of Aeromonas sobria and in silico analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, S.; Borges, A.; Gomes, I.B.; Sousa, S.F.; Simões, M. Curcumin and 10-undecenoic acid as natural quorum sensing inhibitors of LuxS/AI-2 of Bacillus subtilis and LasI/LasR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Food Res. Int. 2023, 165, 112519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulrahman, H.; Misba, L.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, A.U. Curcumin induced photodynamic therapy mediated suppression of quorum sensing pathway of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: An approach to inhibit biofilm in vitro. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 30, 101645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.H.; Marshall, D.L. Antimicrobial activity of ethanol, glycerol monolaurate or lactic acid against Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1993, 20, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabara, J.J.; Swieczkowski, D.M.; Conley, A.J.; Truant, J.P. Fatty acids and derivatives as antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1972, 2, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, R.; Exner, T.E.; Titz, A. A Biophysical Study with Carbohydrate Derivatives Explains the Molecular Basis of Monosaccharide Selectivity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lectin LecB. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, R.; Wagner, S.; Rox, K.; Varrot, A.; Hauck, D.; Wamhoff, E.-C.; Schreiber, J.; Ryckmans, T.; Brunner, T.; Rademacher, C.; et al. Glycomimetic, Orally Bioavailable LecB Inhibitors Block Biofilm Formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 2537–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicki, J.; Woch, J.; Mościpan, M.; Nowakowska-Bogdan, E. Micellar effect on the direct Fischer synthesis of alkyl glucosides. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2017 539, 13–18. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Park, J.-S.; Choi, H.-Y.; Yoon, S.S.; Kim, W.-G. Terrein is an inhibitor of quorum sensing and c-di-GMP in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A connection between quorum sensing and c-di-GMP. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrein. Version 6.5, Revision Date 20 December 2023. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/DE/de/product/sigma/t5705?srsltid=AfmBOory9kFAwnPgePBFzgs71ECzIj_LE8GZGAo4lxziIEK9f-eytRf_ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Sommer, R.; Rox, K.; Wagner, S.; Hauck, D.; Henrikus, S.S.; Newsad, S.; Arnold, T.; Ryckmans, T.; Brönstrup, M.; Imberty, A.; et al. Anti-biofilm Agents against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A Structure-Activity Relationship Study of C-Glycosidic LecB Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 9201–9216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasorn, A.; Loison, F.; Kangsamaksin, T.; Jongrungruangchok, S.; Ponglikitmongkol, M. Terrein inhibits migration of human breast cancer cells via inhibition of the Rho and Rac signaling pathways. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 39, 1378–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stickler, D.J.; Morris, N.S.; Winters, C. Simple physical model to study formation and physiology of biofilms on urethral catheters. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 310, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loose, M.; Naber, K.G.; Purcell, L.; Wirth, M.P.; Wagenlehner, F.M.E. Anti-Biofilm Effect of Octenidine and Polyhexanide on Uropathogenic Biofilm-Producing Bacteria. Urol. Int. 2021, 105, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Version 15.0, valid from 1 January 2025. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/bacteria/methodology-and-instructions/mic-determination/ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Carbon-13 NMR Spectroscopy. Available online: https://archive.org/details/0338-pdf-breitmaier-e.-voelter-w.-carbon-c-13-nmr-spectroscopy.-3rd-ed.-vch-1990-3527264663/mode/2up (accessed on 29 May 2021).

- Jones, S.M.; Yerly, J.; Hu, Y.; Ceri, H.; Martinuzzi, R. Structure of Proteus mirabilis biofilms grown in artificial urine and standard laboratory media. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007, 268, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hola, V.; Peroutkova, T.; Ruzicka, F. Virulence factors in Proteus bacteria from biofilm communities of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 65, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Substance | MIC [µg/mL] |

|---|---|

| Curcumin and Soluplus® | >512 (Curcumin) and >5120 (Soluplus®) |

| Curcumin | not determined |

| Soluplus® | >5120 |

| 1-Monolaurin | >512 |

| 1-Monolaurin and Soluplus® | >512 (1-Monolaurin) and >5120 (Soluplus®) |

| Prontosan® | 16/32 |

| Terrein | 512 |

| Terrein and Prontosan® | 128 (Terrein) and 32 (Prontosan®) |

| n-Undecyl-α/β-l-Fucopyranoside | not determined |

| Piperacillin | 4 |

| Substance | Abbreviation | Literature | Vendor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curcumin and Soluplus® | CURC and SOL | ||

| Curcumin | CURC | Abdulrahman et al. 2020 [23] | Merck Millipore # CAS 458-37-7 |

| Soluplus® | SOL | Hendrik Hardung et al. [13] | BASF SE Ludwigshafen am Rhein Germany |

| 1-Monolaurin | ML | Oh, and Marshall 1993 [24]; Kabara et al. 1972 [25] | TCI # CAS RN®: 142-18-7 |

| 1-Monolaurin & Soluplus® | ML and SOL | ||

| Prontosan® | PRT | Loose et al. 2021 [34] | B. Braun Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany |

| Terrein | TER | Kim et al. 2018 [29] | AdipoGen # CAS-No. 582-46-7 |

| Terrein and Prontosan® | TER and PRT | ||

| n-Undecyl-α/β-l-Fucopyranoside | nU-Fuc | Nowicki et al. 2017 [28]; Sommer et al. 2018 [27] | Laboratory synthesis |

| Piperacillin | PIP | EUCAST QC Tables [35] | Sigma-Aldrich # CAS-No. 66258-76-2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vogel, C.D.; Aust, A.C.; Wende, R.C.; Schagdarsurengin, U.; Wagenlehner, F. Activity of Natural Substances and n-Undecyl-α/β-l-Fucopyranoside Against the Formation of Pathogenic Biofilms by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010076

Vogel CD, Aust AC, Wende RC, Schagdarsurengin U, Wagenlehner F. Activity of Natural Substances and n-Undecyl-α/β-l-Fucopyranoside Against the Formation of Pathogenic Biofilms by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010076

Chicago/Turabian StyleVogel, Christian Dietrich, Anne Christine Aust, Raffael Christoph Wende, Undraga Schagdarsurengin, and Florian Wagenlehner. 2026. "Activity of Natural Substances and n-Undecyl-α/β-l-Fucopyranoside Against the Formation of Pathogenic Biofilms by Pseudomonas aeruginosa" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010076

APA StyleVogel, C. D., Aust, A. C., Wende, R. C., Schagdarsurengin, U., & Wagenlehner, F. (2026). Activity of Natural Substances and n-Undecyl-α/β-l-Fucopyranoside Against the Formation of Pathogenic Biofilms by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiotics, 15(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010076