Comparative Genomic and Resistance Analysis of ST859-KL19 and ST11 Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with Diverse Capsular Serotypes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

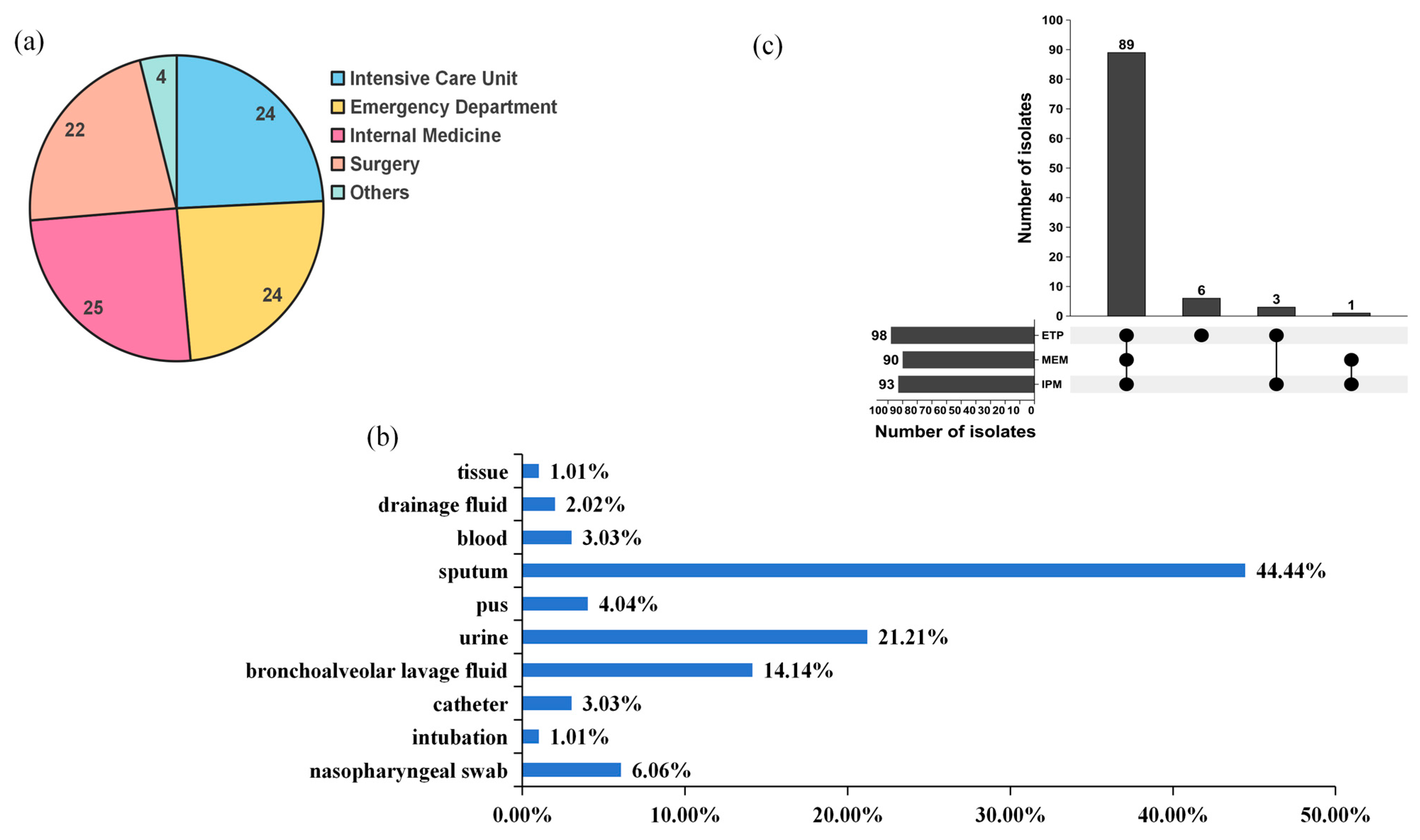

2.1. Antibiotic Susceptibility Profiles

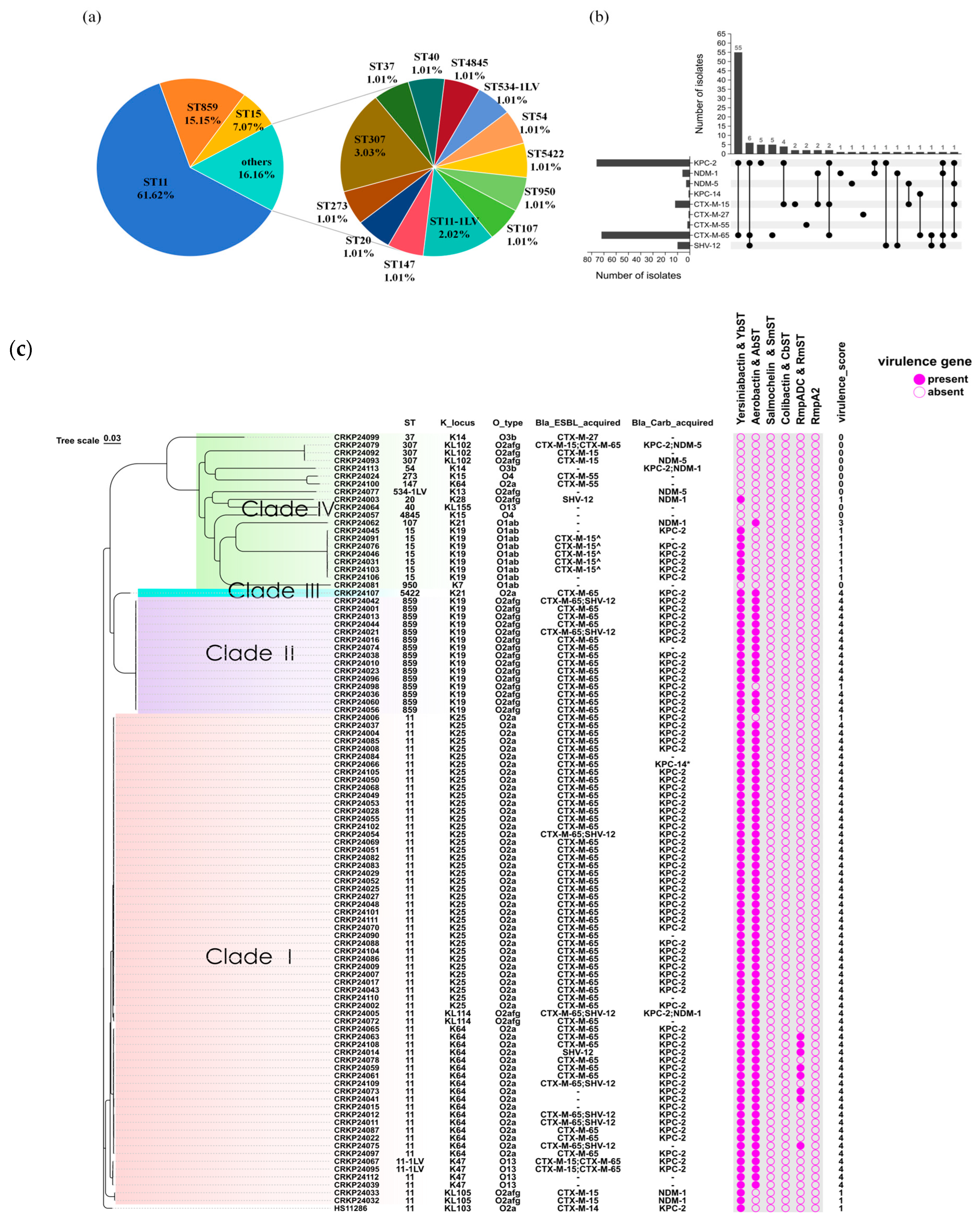

2.2. Genome Analysis

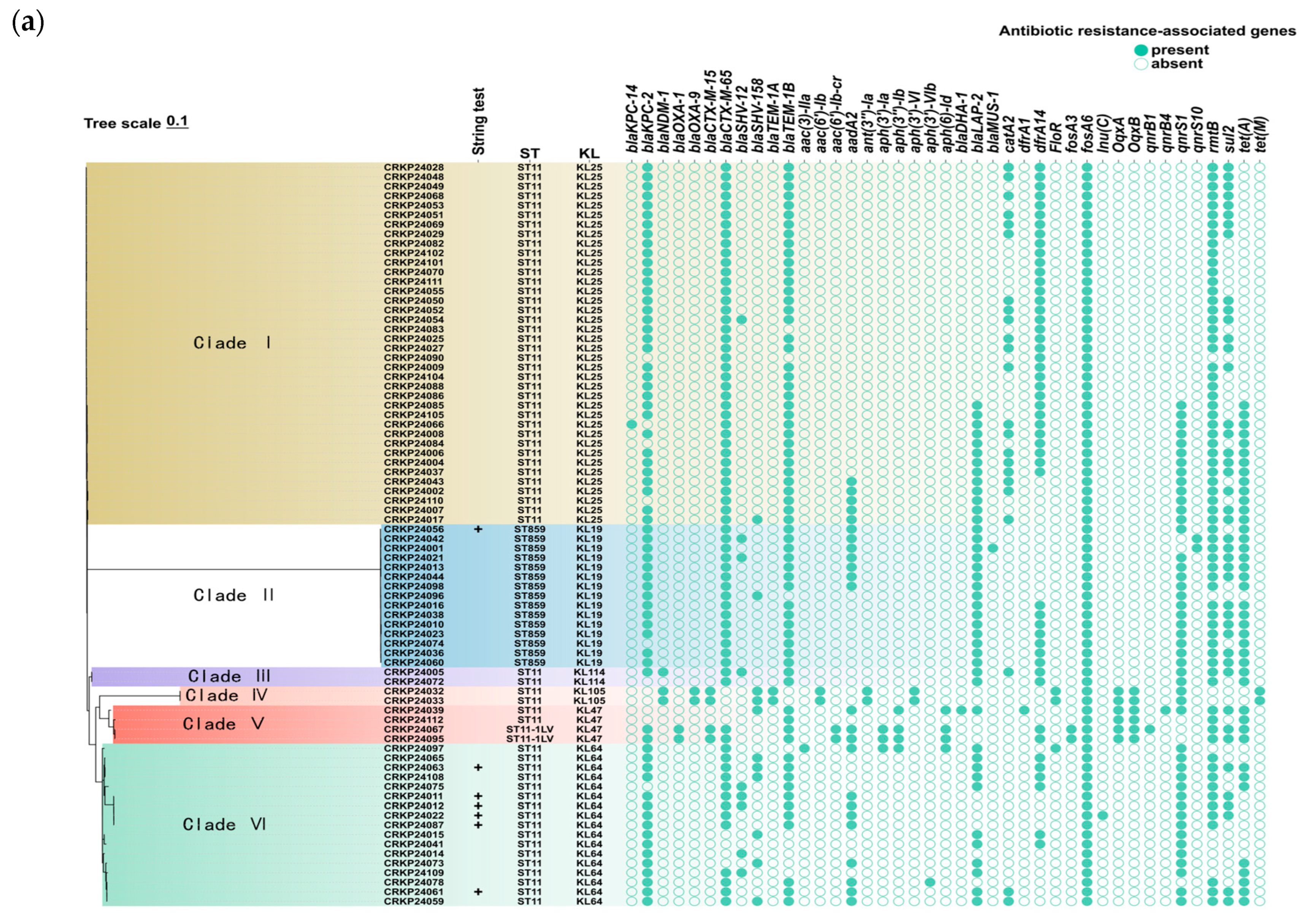

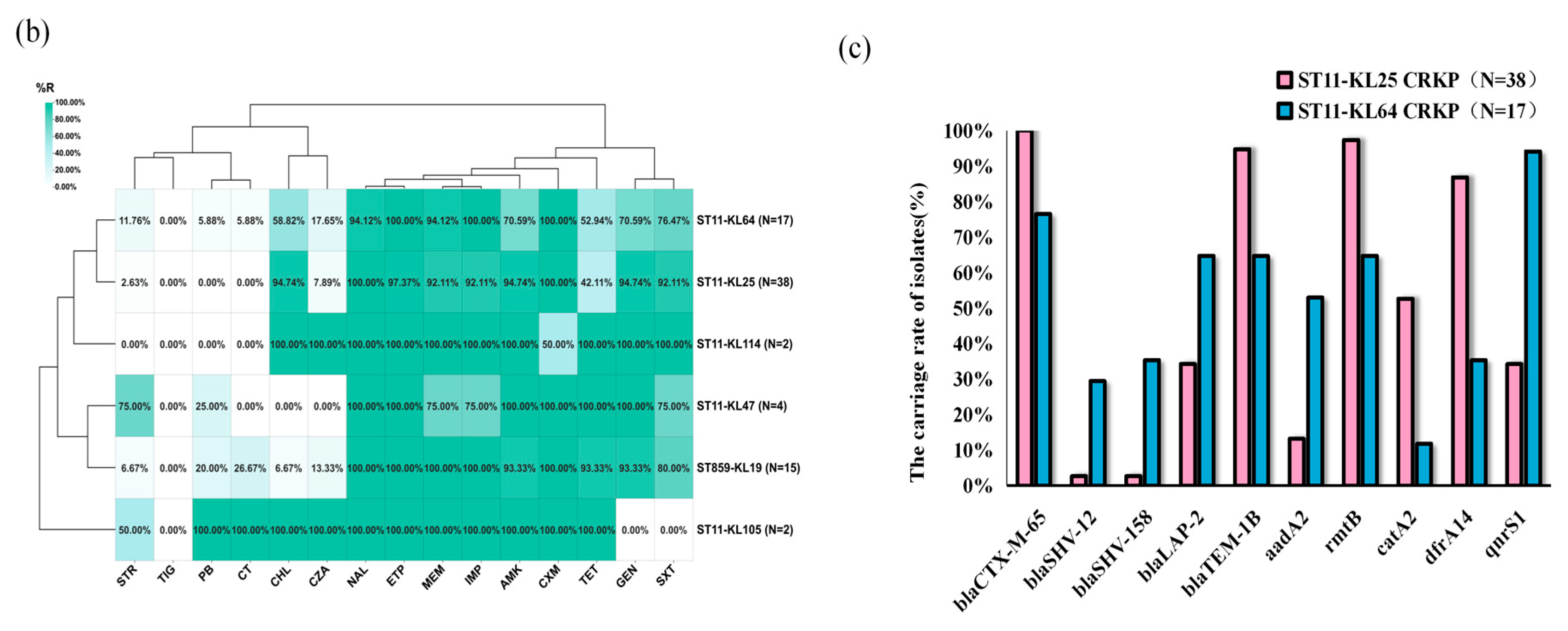

2.3. Comparison of Antimicrobial Resistance Between ST859 and ST11 CRKP

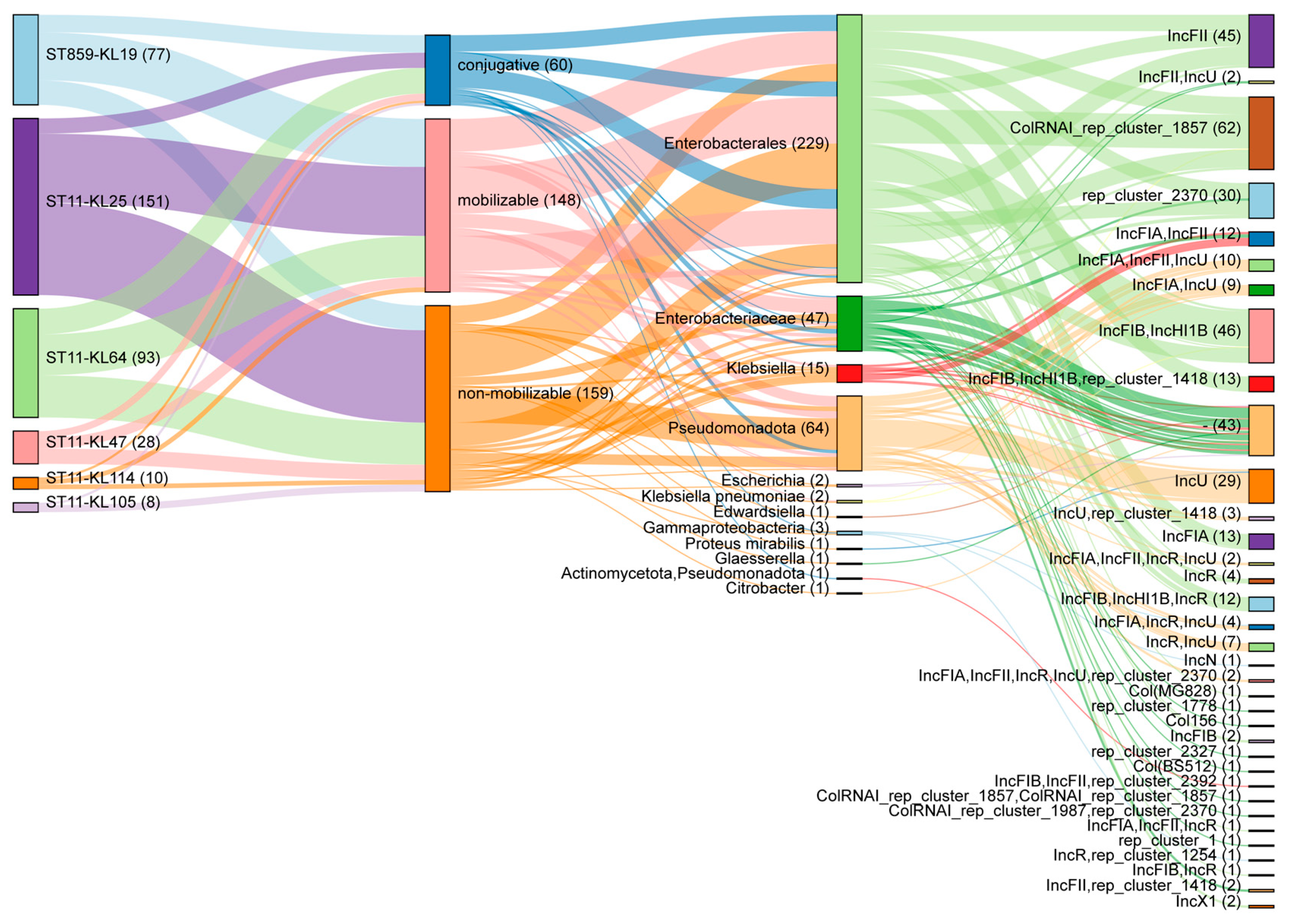

2.4. Plasmid Profiling of ST859 and ST11 CRKP

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Isolation and Identification of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae

4.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

4.3. String Test

4.4. Whole Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Annotation

4.5. Bioinformatic and Phylogenetic Analyses

4.6. Determining Plasmid Mobility

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sati, H.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Hansen, P.; Garlasco, J.; Campagnaro, E.; Boccia, S.; Castillo-Polo, J.A.; Magrini, E.; Garcia-Vello, P.; et al. The WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024: A prioritisation study to guide research, development, and public health strategies against antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Lei, Z.; Fan, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, Q.; Ma, Y.; Lu, B. Tracking international and regional dissemination of the KPC/NDM co-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampatakis, T.; Tsergouli, K.; Behzadi, P. Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: Virulence Factors, Molecular Epidemiology and Latest Updates in Treatment Options. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Ruan, Z.; Zhang, P.; Hu, H.; Han, X.; Wang, Z.; Lou, T.; Quan, J.; Lan, W.; Weng, R.; et al. Epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in China and the evolving trends of predominant clone ST11: A multicentre, genome-based study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 79, 2292–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liang, J.; Zhang, H.; Guo, J.; Li, S.; Li, M. Emergence and clinical challenges of ST11-K64 carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: Molecular insights and implications for antimicrobial resistance and virulence in Southwest China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wang, Y.; Chi, X.; Xiong, L.; Lu, P.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Q.; Shen, P.; Xiao, Y. Genetic, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance characteristics associated with distinct morphotypes in ST11 carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Virulence 2024, 15, 2349768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Dong, N.; Zheng, Z.; Lin, D.; Huang, M.; Wang, L.; Chan, E.W.-C.; Shu, L.; Yu, J.; Zhang, R.; et al. A fatal outbreak of ST11 carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Chinese hospital: A molecular epidemiological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Lei, Z.; Zhuo, X.; Yang, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, B. Two outbreak cases involving ST65-KL2 and ST11-KL64 hypervirulent carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: Similarity and diversity analysis. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhao, R.; Yan, J.; Wu, D. Analysis of the Association Between Antimicrobial Resistance Genes and Virulence Factors in ST11 and Non-ST11 CR-KP Bloodstream Infections in the Intensive Care Unit. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 17, 4011–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhao, L.; Li, M. An Outbreak of ST859-K19 Carbapenem-Resistant Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Chinese Teaching Hospital. mSystems 2022, 7, e0129721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Han, R.; Guo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, S.; Ding, L.; Zhang, R.; Yin, D.; Hu, F. Multiple Novel Ceftazidime-Avibactam-Resistant Variants of blaKPC-2-Positive Klebsiella pneumoniae in Two Patients. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0171421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, D.; Liang, Y.; Cui, J.; He, K.; He, D.; Liu, J.; Hu, G.; Yuan, L. Characterization of a Tigecycline-Resistant and blaCTX-M-Bearing Klebsiella pneumoniae Strain from a Peacock in a Chinese Zoo. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e0176422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Follador, R.; Heinz, E.; Wyres, K.L.; Ellington, M.J.; Kowarik, M.; Holt, K.E.; Thomson, N.R. The diversity of Klebsiella pneumoniae surface polysaccharides. Microb. Genom. 2016, 2, e000073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W. Virulence evolution, molecular mechanisms of resistance and prevalence of ST11 carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in China: A review over the last 10 years. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 23, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Shi, Q.; Hu, D.; Fang, L.; Mao, Y.; Lan, P.; Han, X.; Zhang, P.; Hu, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. The Emergence of Novel Sequence Type Strains Reveals an Evolutionary Process of Intraspecies Clone Shifting in ICU-Spreading Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 691406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, C.; Wang, B.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Guo, Y.; Wu, X.; Yu, J.; Rao, L.; Wang, X.; et al. Characterization difference of typical KL1, KL2 and ST11-KL64 hypervirulent and carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Drug Resist. Updates 2023, 67, 100918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, R.; Wang, S.; Zhang, A.; Duan, Q.; Sun, S.; Jin, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; et al. Expansion and transmission dynamics of high risk carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae subclones in China: An epidemiological, spatial, genomic analysis. Drug Resist. Updates 2024, 74, 101083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Jin, J.; Peng, M.; Xu, L.; Gu, L.; Bao, D.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, K. Genomic Characteristics of a Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Co-Carrying bla NDM-5 and blaKPC-2 Capsular Type KL25 Recovered from a County Level Hospital in China. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 17, 3979–3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Xu, C.; Ma, W.; Li, Q.; Jia, W.; Wang, P. Genomic characterization of ST11-KL25 hypervirulent KPC-2-producing multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae from China. iScience 2024, 27, 11471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Li, Q.; Peng, C.; Lin, T.; Du, H.; Tang, C.; Zhang, X. Molecular and epidemiological characterization of carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae in Huaian, China (2022–2024): A retrospective study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1569004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, R.; Wang, R.; Kang, J.; Duan, J.; Wang, H. ST11 carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clone harbouring capsular type KL25 becomes the primarily prevalent capsular serotype in a tertiary teaching hospital in China. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 43, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Hu, D. The making of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zhu, Y.; Jia, P.; Li, C.; Chu, X.; Sun, T.; Liu, X.; Yu, W.; Chen, F.; Xu, Y.; et al. The key role of iroBCDN-lacking pLVPK-like plasmid in the evolution of the most prevalent hypervirulent carbapenem-resistant ST11-KL64 Klebsiella pneumoniae in China. Drug Resist. Updates 2024, 77, 101137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Yan, Q.; Tao, L.; Ou, Y.; Yang, N.; Yan, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, P. Genome Sequencing and Comparative Genomic Analysis of Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Neurological Intensive Care Unit. Infect. Drug Resist. 2025, 18, 4067–4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Dong, N.; Chan, E.W.C.; Chen, S.; Zhang, R. Molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in China, 2016–2020. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 167–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; He, Z.; Li, Y.; Sun, B. Epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae ST15 of producing KPC-2, SHV-106 and CTX-M-15 in Anhui, China. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, L.; Shen, S.; Chen, J.; Tian, Z.; Shi, Q.; Han, R.; Guo, Y.; Hu, F. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase variants: The new threat to global public health. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 36, e0000823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.Q.; Sri La Sri Ponnampalavanar, S.; Wong, J.H.; Kong, Z.X.; Ngoi, S.T.; Karunakaran, R.; Lau, M.Y.; Abdul Jabar, K.; Teh, C.S.J. Investigation on the mechanisms of carbapenem resistance among the non-carbapenemase-producing carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1464816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Ismail, D.; Campos-Madueno, E.I.; Donà, V.; Endimiani, A. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae (hvKp): Overview, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Detection. Pathog. Immun. 2025, 10, 80–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, T.A.; Olson, R.; Fang, C.-T.; Stoesser, N.; Miller, M.; MacDonald, U.; Hutson, A.; Barker, J.H.; La Hoz, R.M.; Johnson, J.R.; et al. Identification of Biomarkers for Differentiation of Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae from Classical K. pneumoniae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e00776-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, T.A.; Marr, C.M. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00001-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.M.C.; Wick, R.R.; Watts, S.C.; Cerdeira, L.T.; Wyres, K.L.; Holt, K.E. A genomic surveillance framework and genotyping tool for Klebsiella pneumoniae and its related species complex. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyres, K.L.; Lam, M.M.C.; Holt, K.E. Population genomics of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Mcnally, A.; Zong, Z. Call for prudent use of the term hypervirulence in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 101090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macesic, N.; Nelson, B.; Mcconville, T.H.; Giddins, M.J.; A Green, D.; Stump, S.; Gomez-Simmonds, A.; Annavajhala, M.K.; Uhlemann, A.-C. Emergence of Polymyxin Resistance in Clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae Through Diverse Genetic Adaptations: A Genomic, Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 70, 2084–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, D.; Zhao, J.; Lu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhuo, X.; Cao, B. Within-host resistance evolution of a fatal ST11 hypervirulent carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2023, 61, 106747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An. international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochan, T.J.; Nozick, S.H.; Valdes, A.; Mitra, S.D.; Cheung, B.H.; Lebrun-Corbin, M.; Medernach, R.L.; Vessely, M.B.; Mills, J.O.; Axline, C.M.R.; et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates with features of both multidrug-resistance and hypervirulence have unexpectedly low virulence. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kille, B.; Nute, M.G.; Huang, V.; Kim, E.; Phillippy, A.M.; Treangen, T.J. Parsnp 2.0: Scalable core-genome alignment for massive microbial datasets. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Chen, Y.; Cai, G.; Cai, R.; Hu, Z.; Wang, H. Tree Visualization By One Table (tvBOT): A web application for visualizing, modifying and annotating phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W587–W592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Nash, J.H.E. MOB-suite: Software tools for clustering, reconstruction and typing of plasmids from draft assemblies. Microb. Genom. 2018, 4, e000206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Categories of Antibiotics | Antibiotics | No. | %R | No. | %I | No. | %S | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-lactams | Penicillins | Ampicillin | 99 | 100.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Ampicillin/sulbactam | 97 | 97.98% | 1 | 1.01% | 1 | 1.01% | ||

| Cephalosporins | Ceftazidime/avibactam | 21 | 21.21% | 0 | 0.00% | 78 | 78.79% | |

| Cefoxitin | 98 | 98.99% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 1.01% | ||

| Cefuroxime | 96 | 96.97% | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 3.03% | ||

| Ceftiofur | 96 | 96.97% | 1 | 1.01% | 2 | 2.02% | ||

| Cefazolin | 98 | 98.99% | 1 | 1.01% | 0 | 0.00% | ||

| Ceftazidime | 97 | 97.98% | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 2.02% | ||

| Cefepime | 97 | 97.98% | 1 | 1.01% | 1 | 1.01% | ||

| Carbapenems | Imipenem | 93 | 93.94% | 2 | 2.02% | 4 | 4.04% | |

| Ertapenem | 98 | 98.99% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 1.01% | ||

| Meropenem | 90 | 90.91% | 3 | 3.03% | 6 | 6.06% | ||

| Aminoglycosides | Amikacin | 78 | 78.79% | 3 | 3.03% | 18 | 18.18% | |

| Streptomycin | 12 | 12.12% | 0 | 0.00% | 87 | 87.88% | ||

| Gentamicin | 82 | 82.83% | 1 | 1.01% | 16 | 16.16% | ||

| Quinolons | Ciprofloxacin | 97 | 97.98% | 1 | 1.01% | 1 | 1.01% | |

| Nalidixic acid | 95 | 95.96% | 0 | 0.00% | 4 | 4.04% | ||

| Sulfonamides | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 80 | 80.81% | 0 | 0.00% | 19 | 19.19% | |

| Tetracyclines | Tigecycline | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 99 | 100.00% | |

| Tetracycline | 58 | 58.59% | 10 | 10.10% | 31 | 31.31% | ||

| Polypeptide | Polymyxin B | 7 | 7.07% | 92 | 92.93% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Colistin | 10 | 10.10% | 89 | 89.90% | 0 | 0.00% | ||

| Chloramphenicol | 62 | 62.63% | 18 | 18.18% | 19 | 19.19% | ||

| Antimicrobial Agent | ST11 CRKP (n = 63) | ST859 CRKP (n = 15) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | %R | No. | %R | ||

| Ampicillin | 63 | 100.00% | 15 | 100.00% | / |

| Ampicillin/sulbactam | 63 | 100.00% | 15 | 100.00% | / |

| Ceftazidime/avibactam | 10 | 15.87% | 2 | 13.33% | 1.000 |

| Cefoxitin | 63 | 100.00% | 15 | 100.00% | / |

| Cefuroxime | 62 | 98.41% | 15 | 100.00% | 1.000 |

| Ceftiofur | 63 | 100.00% | 15 | 100.00% | / |

| Cefazolin | 63 | 100.00% | 15 | 100.00% | / |

| Ceftazidime | 63 | 100.00% | 15 | 100.00% | / |

| Cefepime | 63 | 100.00% | 15 | 100.00% | / |

| Imipenem | 59 | 93.65% | 15 | 100.00% | 0.726 |

| Ertapenem | 62 | 98.41% | 15 | 100.00% | 1.000 |

| Meropenem | 58 | 92.06% | 15 | 100.00% | 0.577 |

| Amikacin | 56 | 88.89% | 14 | 93.33% | 0.971 |

| Streptomycin | 7 | 11.11% | 1 | 6.67% | 0.971 |

| Gentamicin | 54 | 85.71% | 14 | 93.33% | 0.716 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 63 | 100.00% | 15 | 100.00% | / |

| Nalidixic acid | 62 | 98.41% | 15 | 100.00% | 1.000 |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 53 | 84.13% | 12 | 80.00% | 1.000 |

| Tigecycline | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | / |

| Tetracycline | 33 | 52.38% | 14 | 93.33% | 0.004 * |

| Polymyxin B | 4 | 6.35% | 3 | 20.00% | 0.246 |

| Colistin | 3 | 4.76% | 4 | 26.67% | 0.030 * |

| Chloramphenicol | 50 | 79.37% | 1 | 6.67% | <0.001 * |

| Categories of Antibiotics | Antibiotics | ST11-KL64 CRKP (n = 17) | ST11-KL25 CRKP (n = 38) | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | %R | No. | %R | ||||

| β-lactams | Penicillins | Ampicillin | 17 | 100.00% | 38 | 100.00% | / |

| Ampicillin/sulbactam | 17 | 100.00% | 38 | 100.00% | / | ||

| Cephalosporins | Ceftazidime/avibactam | 3 | 17.65% | 3 | 7.89% | 0.546 | |

| Cefoxitin | 17 | 100.00% | 38 | 100.00% | / | ||

| Cefuroxime | 17 | 100.00% | 38 | 100.00% | / | ||

| Ceftiofur | 17 | 100.00% | 38 | 100.00% | / | ||

| Cefazolin | 17 | 100.00% | 38 | 100.00% | / | ||

| Ceftazidime | 17 | 100.00% | 38 | 100.00% | / | ||

| Cefepime | 17 | 100.00% | 38 | 100.00% | / | ||

| Carbapenems | Imipenem | 17 | 100.00% | 35 | 92.11% | 0.583 | |

| Ertapenem | 17 | 100.00% | 37 | 97.37% | 1.000 | ||

| Meropenem | 16 | 94.12% | 35 | 92.11% | 1.000 | ||

| Aminoglycosides | Amikacin | 12 | 70.59% | 36 | 94.74% | 0.041 * | |

| Streptomycin | 2 | 11.76% | 1 | 2.63% | 0.462 | ||

| Gentamicin | 12 | 70.59% | 36 | 94.74% | 0.041 * | ||

| Quinolons | Ciprofloxacin | 17 | 100.00% | 38 | 100.00% | / | |

| Nalidixic acid | 16 | 94.12% | 38 | 100.00% | 0.677 | ||

| Sulfonamides | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 13 | 76.47% | 35 | 92.11% | 0.242 | |

| Tetracyclines | Tigecycline | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | / | |

| Tetracycline | 9 | 52.94% | 16 | 42.11% | 0.456 | ||

| Polypeptide | Polymyxin B | 1 | 5.88% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.677 | |

| Colistin | 1 | 5.88% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.677 | ||

| Chloramphenicols | Chloramphenicol | 10 | 58.82% | 36 | 94.74% | 0.003 * | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Feng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, B.; Liang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Ren, L. Comparative Genomic and Resistance Analysis of ST859-KL19 and ST11 Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with Diverse Capsular Serotypes. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010040

Wang X, Feng J, Zhang Y, Qiu Y, Yang B, Liang Y, Wang Y, Zhao B, Ren L. Comparative Genomic and Resistance Analysis of ST859-KL19 and ST11 Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with Diverse Capsular Serotypes. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiao, Jun Feng, Yue Zhang, Ye Qiu, Bowen Yang, Yanru Liang, Yuanping Wang, Bing Zhao, and Lili Ren. 2026. "Comparative Genomic and Resistance Analysis of ST859-KL19 and ST11 Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with Diverse Capsular Serotypes" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010040

APA StyleWang, X., Feng, J., Zhang, Y., Qiu, Y., Yang, B., Liang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhao, B., & Ren, L. (2026). Comparative Genomic and Resistance Analysis of ST859-KL19 and ST11 Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with Diverse Capsular Serotypes. Antibiotics, 15(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010040