An Assessment of the Knowledge and Attitudes of Final-Year Dental Students on and Towards Antibiotic Use: A Questionnaire Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Power Analysis

4.2. Statistical Analysis

4.3. Ethical Approval

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thabit, A.K.; Aljereb, N.M.; Khojah, O.M.; Shanab, H.; Badahdah, A. Towards Wiser Prescribing of Antibiotics in Dental Practice: What Pharmacists Want Dentists to Know. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuderer, J.G.; Hoferer, F.; Eichberger, J.; Fiedler, M.; Gessner, A.; Hitzenbichler, F.; Gottsauner, M.; Maurer, M.; Meier, J.K.; Reichert, T.E.; et al. Predictors for prolonged and escalated perioperative antibiotic therapy after microvascular head and neck reconstruction: A comprehensive analysis of 446 cases. Head. Face Med. 2024, 20, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momand, P.; Naimi-Akbar, A.; Hultin, M.; Lund, B.; Götrick, B. Is routine antibiotic prophylaxis warranted in dental implant surgery to prevent early implant failure?—A systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karemore, T.V.; Ashtankar, K.A.; Motwani, M. Comparative efficacy of pre-operative and post-operative administration of amoxicillin in third molar extraction surgery—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 15, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lollobrigida, M.; Pingitore, G.; Lamazza, L.; Mazzucchi, G.; Serafini, G.; De Biase, A. Antibiotics to Prevent Surgical Site Infection (SSI) in Oral Surgery: Survey among Italian Dentists. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cigerim, L.; Orhan, Z.D.; Kaplan, V.; Cigerim, S.C.; Feslihan, E. Evaluation of the efficacy of topical rifamycin application on postoperative complications after lower impacted wisdom teeth surgery. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 125, 101501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagoni, T.G.; Rafalovich, V.C.; Brozoski, M.A.; Deboni, M.C.Z.; de Oliveira, N.K. Selective outcome reporting concerning antibiotics and third molar surgery. Clin. Oral Investig. 2025, 29, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quah, B.; Yong, C.W.; Lai, C.W.M.; Islam, I. Efficacy of adjunctive modalities during tooth extraction for the prevention of osteoradionecrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 3732–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Zheng, Y.; Bi, L. Is Antibiotic Prophylaxis Reasonable in Parotid Surgery? Retrospective Analysis of Surgical Site Infection. Surg. Infect. 2024, 25, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbricoli, L.; Grisolia, G.; Stellini, E.; Bacci, C.; Annunziata, M.; Bressan, E. Antibiotic-Prescribing Habits in Dentistry: A Questionnaire-Based Study. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteagoitia, M.I.; Ramos, E.; Santamaría, G.; Álvarez, J.; Barbier, L.; Santamaría, J. Survey of Spanish dentists on the prescription of antibiotics and antiseptics in surgery for impacted lower third molars. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2016, 21, e82–e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barone, A.; Chatelain, S.; Derchi, G.; Di Spirito, F.; Martuscelli, R.; Porzio, M.; Sbordone, L. Antibiotic’s effectiveness after erupted tooth extractions: A retrospective study. Oral Dis. 2020, 26, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchionni, S.; Toti, P.; Barone, A.; Covani, U.; Esposito, M. The effectiveness of systemic antibiotic prophylaxis in preventing local complications after tooth extraction. A systematic review. Eur. J. Oral Implantol. 2017, 10, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cinquini, C.; Marchionni, S.; Derchi, G.; Miccoli, M.; Gabriele, M.; Barone, A. Non-impacted tooth extractions and antibiotic treatment: A RCT study. Oral Dis. 2021, 27, 1042–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Hu, J. Prophylactic therapy for prevention of surgical site infection after extraction of third molar: An overview of reviews. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2023, 28, e581–e587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blondeau, F.; Daniel, N.G. Extraction of impacted mandibular third molars: Postoperative complications and their risk factors. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2007, 73, 325. [Google Scholar]

- Candotto, V.; Oberti, L.; Gabrione, F.; Scarano, A.; Rossi, D.; Romano, M. Complication in third molar extractions. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2019, 33 (Suppl. S1), 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Alghamdi, H.; Leventis, M.; Deliberador, T. Management of Infected Tissues Around Dental Implants: A Short Narrative Review. Braz. Dent. J. 2024, 35, e246160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Sánchez, F.; Arteagoitia, I.; Rodríguez Andrés, C.; Caiazzo, A. Antibiotic prophylaxis habits in oral implant surgery among dentists in Italy: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Wu, Y.; Wan, Z.; Shen, D. Pathogenesis and treatment of wound healing in patients with diabetes after tooth extraction. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 949535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, D.J.; Sambrook, P.J.; Goss, A.N. The healing of dental extraction sockets in insulin-dependent diabetic patients: A prospective controlled observational study. Aust. Dent. J. 2019, 64, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sykara, M.; Maniatakos, P.; Tentolouris, A.; Karoussis, I.K.; Tentolouris, N. The necessity of administrating antibiotic prophylaxis to patients with diabetes mellitus prior to oral surgical procedures-a systematic review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2022, 16, 102621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Fan, B.; Wu, T.; Li, Z.; Yu, X.; Zhang, B. Special diffusion pathway of pericoronitis of the third molar: A case report and literature review. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2024, 119, 109709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, J.; Kunderova, M.; Pilbauerova, N.; Kapitan, M. A Review of Evidence-Based Recommendations for Pericoronitis Management and a Systematic Review of Antibiotic Prescribing for Pericoronitis among Dentists: Inappropriate Pericoronitis Treatment Is a Critical Factor of Antibiotic Overuse in Dentistry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, D.; Roldán, S.; Sanz, M. The periodontal abscess: A review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2000, 27, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabras, M.; Gambino, A.; Broccoletti, R.; Sciascia, S.; Arduino, P.G. Lack of evidence in reducing risk of MRONJ after teeth extractions with systemic antibiotics. J. Oral Sci. 2021, 63, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, B.G.; Schellevis, F.; Stobberingh, E.; Goossens, H.; Pringle, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of antibiotic consumption on antibiotic resistance. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costelloe, C.; Metcalfe, C.; Lovering, A.; Mant, D.; Hay, A.D. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010, 340, c2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, W.W.; Cross, C.L. Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

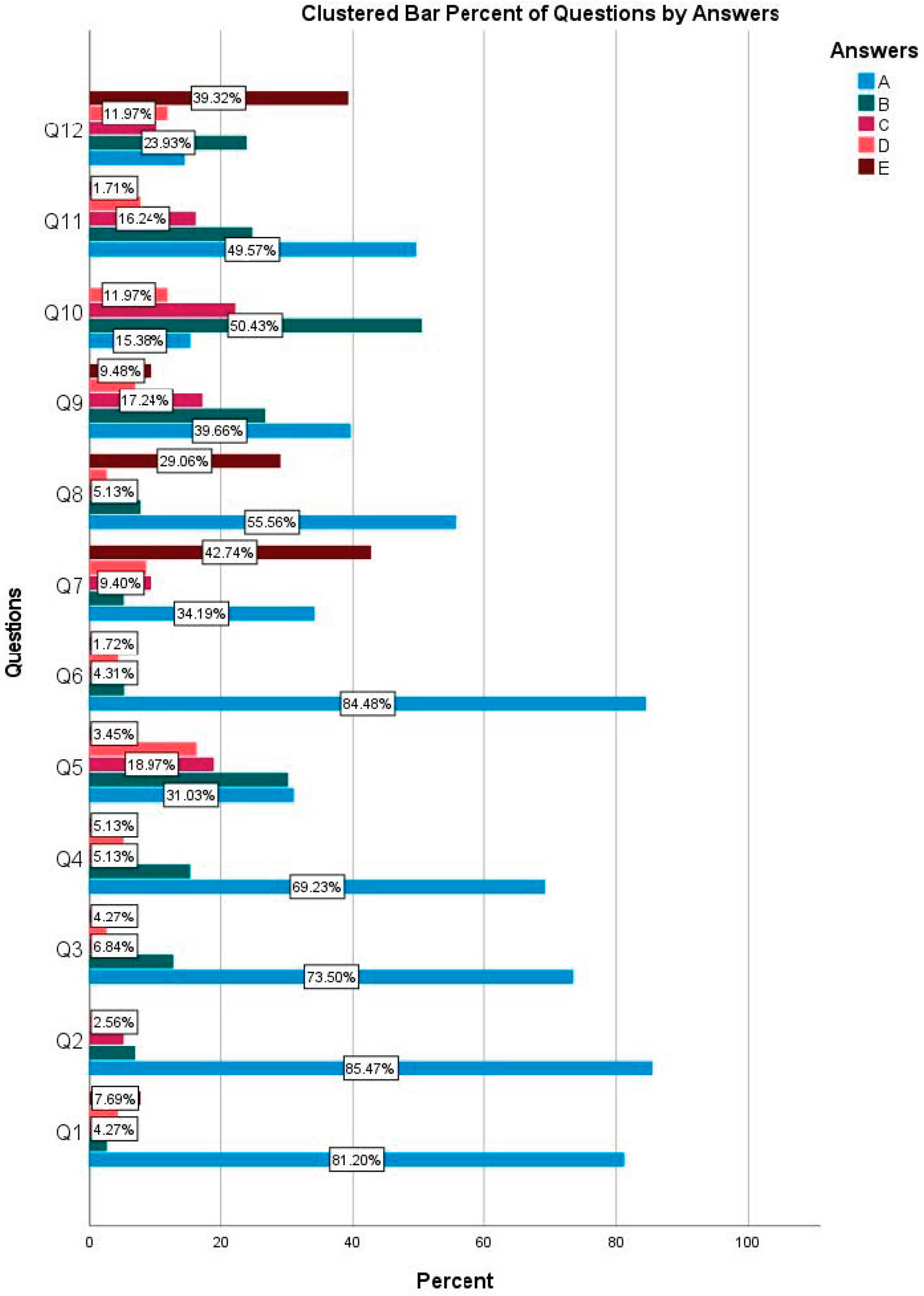

| A | B | C | D | E | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | Test Statistics | p-Value | |

| Q1 | 95 | 81.2 | 3 | 2.6 | 5 | 4.3 | 5 | 4.3 | 9 | 7.7 | 274.667 | <0.001 * |

| Q2 | 100 | 85.5 | 8 | 6.8 | 6 | 5.1 | 3 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 228.607 | <0.001 * |

| Q3 | 86 | 73.5 | 15 | 12.8 | 8 | 6.8 | 3 | 2.6 | 5 | 4.3 | 212.872 | <0.001 * |

| Q4 | 81 | 69.2 | 18 | 15.4 | 6 | 5.1 | 6 | 5.1 | 6 | 5.1 | 181.846 | <0.001 * |

| Q5 | 36 | 31.0 | 35 | 30.2 | 22 | 19.0 | 19 | 16.4 | 4 | 3.4 | 29.776 | <0.001 * |

| Q6 | 98 | 84.5 | 6 | 5.2 | 5 | 4.3 | 5 | 4.3 | 2 | 1.7 | 301.845 | <0.001 * |

| Q7 | 40 | 34.2 | 6 | 5.1 | 11 | 9.4 | 10 | 8.5 | 50 | 42.7 | 69.197 | <0.001 * |

| Q8 | 65 | 55.6 | 9 | 7.7 | 6 | 5.1 | 3 | 2.6 | 34 | 29.1 | 118.342 | <0.001 * |

| Q9 | 46 | 39.7 | 31 | 26.7 | 20 | 17.2 | 8 | 6.9 | 11 | 9.5 | 41.845 | <0.001 * |

| Q10 | 18 | 15.4 | 59 | 50.4 | 26 | 22.2 | 14 | 12.0 | 58 | 49.6 | 42.897 | <0.001 * |

| Q11 | 58 | 49.6 | 29 | 24.8 | 19 | 16.2 | 9 | 7.7 | 2 | 1.7 | 81.761 | <0.001 * |

| Q12 | 17 | 14.5 | 28 | 23.9 | 12 | 10.3 | 14 | 12.0 | 46 | 39.3 | 33.812 | <0.001 * |

| Q1—Non-surgical extraction of tooth 36 in infraocclusion with odontomy in an 11-year-old patient with no history of systemic disease: (a) No antibiotic therapy is applied (b) One dose of broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied 1 h before the procedure (c) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied 1 h before the procedure and continued for up to 5 days after the procedure (d) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied starting 24–48 h before surgery and continued for 3–4 days after the procedure (e) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied for 5–7 days after the procedure Q2—Non-surgical extraction of tooth 24 with extensive caries and no acute or chronic inflammatory lesions in a 56-year-old patient with controlled arterial hypertension, (a) No antibiotic therapy is applied (b) One dose of broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied 1 h before the procedure (c) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied 1 h before the procedure and up to 5 days after the procedure (d) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied starting 24/48 h before the surgery and up to 5 days after the procedure Broad spectrum antibiotics are applied for 3–4 days (e) Broad spectrum antibiotics are applied for 5–7 days after the procedure Q3—Non-surgical extraction of tooth number 26 with grade 3 mobility in an 88-year-old ASA II patient who is on anticoagulants and has controlled hypertension., (a) No antibiotic therapy is applied (b) One dose of broad spectrum antibiotics are applied 1 h before the procedure (c) Broad spectrum antibiotics are applied 1 h before the procedure and up to 5 days after the procedure (d) Broad spectrum antibiotics are applied 24/48 h before the surgery and for 3–4 days after the procedure (e) Broad spectrum antibiotics are applied for 5–7 days after the procedure Q4—Non-surgical extraction of teeth numbers 34 and 35 in a 75-year-old patient with controlled arterial hypertension and well-controlled type II diabetes, without acute or chronic inflammatory lesions, (a) No antibiotic therapy is applied (b) One dose of broad-spectrum antibiotics are applied 1 h before the procedure (c) Broad spectrum antibiotics are applied 1 h before the procedure and up to 5 days after the procedure (d) Broad spectrum antibiotics are applied starting 24/48 h before the surgery and for 3–4 days after the procedure (e) Broad spectrum antibiotics are applied for 5–7 days after the procedure Q5—A 57-year-old patient with a history of myocardial infarction, high cholesterol, anticoagulant medication, and controlled hypertension presents with three root remnants in a single-rooted tooth. Periapical granuloma was detected in two of the roots on the X-ray. For non-surgical extraction of this tooth, (a) No antibiotic therapy (b) One dose of broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied 1 h before the procedure (c) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied 1 h before the procedure and up to 5 days after the procedure (d) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied starting 24/48 h before the surgery and up to 3–4 days after the procedure (e) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied for 5–7 days after the procedure Q6—Non-surgical extraction of five root remnants (teeth 13, 15, 22, 24, and 26) without acute or chronic periapical lesions in a 68-year-old patient with no history of systemic disease, (a) No antibiotic therapy (b) One dose of broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied 1 h before the procedure (c) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied 1 h before the procedure and up to 5 days after the procedure (d) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied starting 24/48 h before the surgery and up to 3–4 days after the procedure (e) Broad spectrum antibiotics are applied for 5–7 days after the procedure Q7—Surgical extraction of tooth number 48, which is completely impacted in mandible, in a 25-year-old patient with no systemic disease, (a) No antibiotic therapy is applied (b) One dose of broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied 1 h before the procedure (c) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied 1 h before the procedure and up to 5 days after the procedure (d) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied starting 24/48 h before the surgery and for 3–4 days after the procedure (e) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied for 5–7 days after the procedure | Q8—Placement of dental implants in the mandibular molar region by raising a mucoperiosteal flap in a 54-year-old patient with no systemic disease, (a) No antibiotic therapy is applied (b) A dose of broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied 1 h before the procedure (c) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied 1 h before the procedure and up to 5 days after the procedure (d) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied starting 24/48 h before surgery and for 3–4 days after the procedure (e) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied for 5–7 days after the procedure Q9—Non-surgical extraction of teeth numbers 14 and 15 in a 55-year-old patient with metabolic syndrome and no acute or chronic periapical lesions (patient’s fasting blood sugar: 160 mg/dL) (a) No antibiotic therapy is applied (b) A dose of broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied 1 h before the procedure (c) Broad-spectrum antibiotic is applied 1 h before the procedure and up to 5 days after the procedure (d) 24/48 h before and 3–4 days after the procedure broad-spectrum antibiotics are applied (e) Broad-spectrum antibiotics are applied for 5–7 days after the procedure Q10—A 17-year-old patient with mild pain in tooth number 38, which has partial bone retention and has been ongoing for 2 days. The patient has no fever or purulent exudate in the pericoronal tissue on clinical examination, but the tissue was found to be erythematous and edematous. In this patient, (a) Broad-spectrum antibiotics and anti-inflammatory/analgesic drugs are prescribed for 5 days, (b) Local antiseptics (chlorhexidine), anti-inflammatory/analgesic drugs and oral hygiene instructions; If there is no regression in symptoms in 3 days, broad-spectrum antibiotics are prescribed for 5 days, (c) Spontaneous regression in symptoms is expected; If there is no regression in symptoms within 3 days, broad-spectrum antibiotics are prescribed for 5 days, (d) Immediate surgical extraction is performed, and broad-spectrum antibiotics are prescribed for 5 days after the procedure. Q11—A 54-year-old male patient presents with a 7 mm diameter fluctuant swelling in the buccal mucosa adjacent to tooth number 26. The tooth is not luxated. Patient has no fever or lymphadenopathy, palpation revealed suppuration in the sulcus, and probing in three different areas of the vestibule revealed pocket depths of 9 mm, 8 mm, and 9 mm. In this patient, (a) Manual and ultrasonic root planing, along with abscess drainage from the pocket, are performed. (b) After manual and ultrasonic root planing and abscess drainage from the pocket, 5 days of broad-spectrum antibiotics are prescribed. (c) Manual and ultrasonic root planing are performed, followed by 5 days of broad-spectrum antibiotics. (d) Following a single dose of antibiotic prophylaxis 1 h before the procedure, the tooth is extracted. (e) Other Q12—A 62-year-old patient who has been using bisphosphonates (70 mg oral sodium alendronate once a week) for 11 years due to osteoporosis has had his treatment interrupted for 30 days. Patient has no other systemic diseases. For non-surgical extraction of the root of this patient’s cervically fractured tooth number 35, (a) A single dose of broad-spectrum antibiotic is used 1 h before surgery and local antiseptic and mouthwash (0.2% chlorhexidine) before extraction (b) Local antiseptic (0.2% chlorhexidine); use of antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin + metronidazole) drugs for 2–3 days before surgery and 5–7 days after surgery (c) Use of local antiseptics (0.2% chlorhexidine); use of antibiotic (amoxicillin + metronidazole) for 5–7 days after surgery (d) Use of local antiseptics (0.2% chlorhexidine); use of antibiotics (amoxicillin + metronidazole) starting 1 day before surgery and continuing until 5–7 days after surgery (e) I refer the patient to an oral surgeon |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yildirim, O.; Yildiz, H.; Mollaoglu, N. An Assessment of the Knowledge and Attitudes of Final-Year Dental Students on and Towards Antibiotic Use: A Questionnaire Study. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 645. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14070645

Yildirim O, Yildiz H, Mollaoglu N. An Assessment of the Knowledge and Attitudes of Final-Year Dental Students on and Towards Antibiotic Use: A Questionnaire Study. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(7):645. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14070645

Chicago/Turabian StyleYildirim, Ozgun, Humeyra Yildiz, and Nur Mollaoglu. 2025. "An Assessment of the Knowledge and Attitudes of Final-Year Dental Students on and Towards Antibiotic Use: A Questionnaire Study" Antibiotics 14, no. 7: 645. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14070645

APA StyleYildirim, O., Yildiz, H., & Mollaoglu, N. (2025). An Assessment of the Knowledge and Attitudes of Final-Year Dental Students on and Towards Antibiotic Use: A Questionnaire Study. Antibiotics, 14(7), 645. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14070645