Combination Therapy with Oral Vancomycin Plus Intravenous Metronidazole Is Not Superior to Oral Vancomycin Alone for the Treatment of Severe Clostridioides difficile Infection: A KASID Multicenter Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Patient Characteristics

2.2. Outcomes

3. Discussion

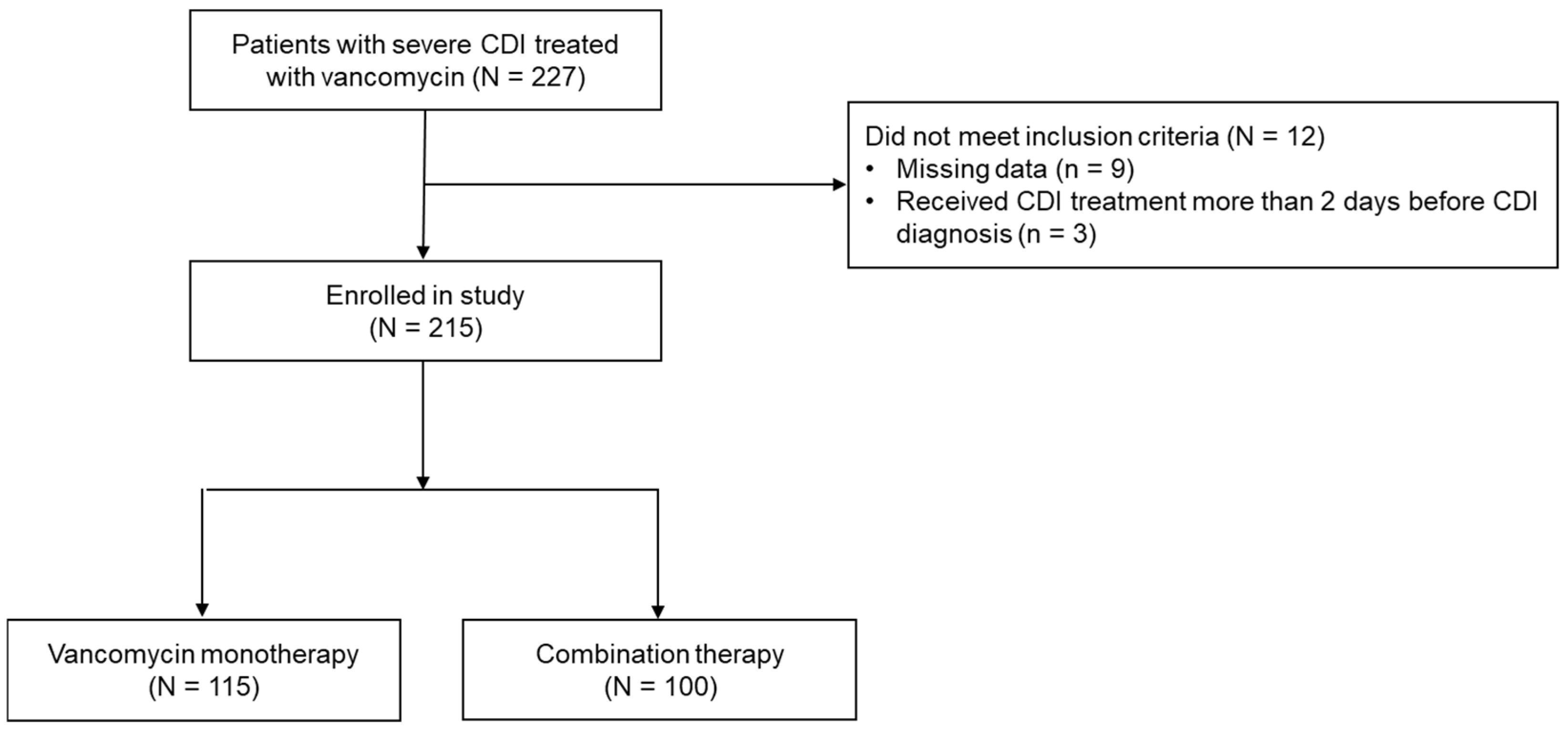

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patient Characteristics

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Outcomes

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guh, A.Y.; Mu, Y.; Winston, L.G.; Johnston, H.; Olson, D.; Farley, M.M.; Wilson, L.E.; Holzbauer, S.M.; Phipps, E.C.; Dumyati, G.K.; et al. Trends in U.S. Burden of Clostridioides difficile Infection and Outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1320–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borren, N.Z.; Ghadermarzi, S.; Hutfless, S.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N. The Emergence of Clostridium difficile Infection in Asia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Incidence and Impact. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Myung, R.; Kim, B.; Kim, J.; Kim, T.; Lee, M.S.; Kim, U.J.; Park, D.W.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, C.S.; et al. Incidence of Clostridioides difficile Infections in Republic of Korea: A Prospective Study with Active Surveillance vs. National Data from Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2024, 39, e118. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, J.M.; Yoon, J.Y.; Kwak, M.S.; Lee, M.; Cho, Y.S. Demographic Characteristics and Economic Burden of Clostridioides difficile Infection in Korea: A Nationwide Population-Based Study after Propensity Score Matching. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Lavergne, V.; Skinner, A.M.; Gonzales-Luna, A.J.; Garey, K.W.; Kelly, C.P.; Wilcox, M.H. Clinical Practice Guideline by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (Idsa) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (Shea): 2021 Focused Update Guidelines on Management of Clostridioides difficile Infection in Adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e1029–e1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.R.; Fischer, M.; Allegretti, J.R.; LaPlante, K.; Stewart, D.B.; Limketkai, B.N.; Stollman, N.H. Acg Clinical Guidelines: Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Clostridioides difficile Infections. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 1124–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokas, K.E.; Johnson, J.W.; Beardsley, J.R.; Ohl, C.A.; Luther, V.P.; Williamson, J.C. The Addition of Intravenous Metronidazole to Oral. Vancomycin Is Associated with Improved Mortality in Critically Ill Patients with Clostridium difficile Infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, A.D.; Heil, E.L.; Blackman, A.L.; Banoub, M.; Johnson, J.K.; Leekha, S.; Claeys, K.C. Evaluation of Addition of Intravenous Metronidazole to Oral Vancomycin Therapy in Critically Ill Patients with Non-Fulminant Severe Clostridioides difficile Infection. Pharmacotherapy 2020, 40, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Schluger, A.; Li, J.; Gomez-Simmonds, A.; Salmasian, H.; Freedberg, D.E. Does Addition of Intravenous Metronidazole to Oral Vancomycin Improve Outcomes in Clostridioides difficile Infection? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2414–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Prehn, J.; Reigadas, E.; Vogelzang, E.H.; Bouza, E.; Hristea, A.; Guery, B.; Krutova, M.; Norén, T.; Allerberger, F.; Coia, J.E.; et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: 2021 Update on the Treatment Guidance Document for Clostridioides difficile Infection in Adults. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, S1–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, S.N.; Bauer, S.R.; Neuner, E.A.; Lam, S.W. Comparison of Treatment Outcomes with Vancomycin Alone Versus Combination Therapy in Severe Clostridium difficile Infection. J. Hosp. Infect. 2013, 85, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, S. My Treatment Approach to Clostridioides difficile Infection. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 2192–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosty, C.; Bortolussi-Courval, É.; Lee, J.; Lee, T.C.; McDonald, E.G. Global Practice Variation in the Management of Clostridioides difficile Infections: An International Cross-Sectional Survey of Clinicians. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, M.M.; Shanholtzer, C.J.; Lee, J.T., Jr.; Gerding, D.N. Ten Years of Prospective Clostridium difficile-Associated Disease Surveillance and Treatment at the Minneapolis Va Medical Center, 1982–1991. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 1994, 15, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Clarke, L.M.; Allegretti, J.R. Review Article: The Epidemiology and Management of Clostridioides difficile Infection—A Clinical Update. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 59, 1335–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, T.; Li, W.; Yang, L.L.; Yang, S.M.; He, Q.; He, H.Y.; Sun, D.L. Systematic Review of Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Clostridioides difficile Infection. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 926482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.S.; Syue, L.S.; Cheng, A.; Yen, T.Y.; Chen, H.M.; Chiu, Y.H.; Hsu, Y.L.; Chiu, C.H.; Su, T.Y.; Tsai, W.L.; et al. Recommendations and Guidelines for the Treatment of Clostridioides difficile Infection in Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020, 53, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunishima, H.; Ohge, H.; Suzuki, H.; Nakamura, A.; Matsumoto, K.; Mikamo, H.; Mori, N.; Morinaga, Y.; Yanagihara, K.; Yamagishi, Y.; et al. Japanese Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Clostridioides (Clostridium) Difficile Infection. J. Infect. Chemother. 2022, 28, 1045–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Lu, L.; Lin, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, X. Efficacy and Safety of Metronidazole Monotherapy Versus Vancomycin Monotherapy or Combination Therapy in Patients with Clostridium difficile Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipitone, G.; Granata, G.; Sartelli, M.; Gizzi, A.; Imburgia, C.; Marsala, L.; Cascio, A.; Iaria, C. On the Use of Intravenous Metronidazole for Severe and Complicated Clostridioides difficile Infection: A Review and Meta-Analysis. Infez. Med. 2024, 32, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Korayem, G.B.; Eljaaly, K.; Matthias, K.R.; Zangeneh, T.T. Oral Vancomycin Monotherapy Versus Combination Therapy in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients with Uncomplicated Clostridium difficile Infection: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Transplant. Proc. 2018, 50, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, S.R.; Bhatt, V.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Schuster, M. A Retrospective Review of Metronidazole and Vancomycin in the Management of Clostridium difficile Infection in Patients with Hematologic Malignancies. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2014, 20, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenisch, J.M.; Schmid, D.; Kuo, H.W.; Allerberger, F.; Michl, V.; Tesik, P.; Tucek, G.; Laferl, H.; Wenisch, C. Prospective Observational Study Comparing Three Different Treatment Regimes in Patients with Clostridium difficile Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 1974–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hames, A.; Perry, J.D.; Gould, F.K. In Vitro Effect of Metronidazole and Vancomycin in Combination on Clostridium difficile. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009, 63, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Erikstrup, L.T.; Aarup, M.; Hagemann-Madsen, R.; Dagnaes-Hansen, F.; Kristensen, B.; Olsen, K.E.; Fuursted, K. Treatment of Clostridium difficile Infection in Mice with Vancomycin Alone Is as Effective as Treatment with Vancomycin and Metronidazole in Combination. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2015, 2, e000038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, S.; Yang, J.; Huang, H. Efficacy Assessment of the Co-Administration of Vancomycin and Metronidazole in Clostridioides difficile-Infected Mice Based on Changes in Intestinal Ecology. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosty, C.; Hanula, R.; Katergi, K.; Longtin, Y.; McDonald, E.G.; Lee, T.C. Clinical Outcomes and Management of Naat-Positive/Toxin-Negative Clostridioides difficile Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 78, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tansarli, G.S.; Falagas, M.E.; Fang, F.C. Clinical Significance of Toxin Eia Positivity in Patients with Suspected Clostridioides difficile Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2025, 63, e0097724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipitone, G.; Iaria, C.; Granata, G.; Cascio, A.; Maraolo, A.E. Which Trials Do We Need? Fidaxomicin Plus Either Intravenous Metronidazole or Tigecycline Versus Vancomycin Plus Either Intravenous Metronidazole or Tigecycline for Fulminant Clostridioides difficile Infection. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2025, 31, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bella, S.; Nisii, C.; Petrosillo, N. Is Tigecycline a Suitable Option for Clostridium difficile Infection? Evidence from the Literature. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 46, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergely Szabo, B.; Kadar, B.; Lenart, K.S.; Dezsenyi, B.; Kunovszki, P.; Fried, K.; Kamotsay, K.; Nikolova, R.; Prinz, G. Use of Intravenous Tigecycline in Patients with Severe Clostridium difficile Infection: A Retrospective Observational Cohort Study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kechagias, K.S.; Chorepsima, S.; Triarides, N.A.; Falagas, M.E. Tigecycline for the Treatment of Patients with Clostridium difficile Infection: An Update of the Clinical Evidence. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, B.; Pai, H. Diversity of Binary Toxin Positive Clostridioides difficile in Korea. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, L.C.; Gerding, D.N.; Johnson, S.; Bakken, J.S.; Carroll, K.C.; Coffin, S.E.; Dubberke, E.R.; Garey, K.W.; Gould, C.V.; Kelly, C.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (Idsa) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (Shea). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, e1–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, M.D.; Alverdy, J.C.; Hall, D.E.; Simmons, R.L.; Zuckerbraun, B.S. Diverting Loop Ileostomy and Colonic Lavage: An Alternative to Total Abdominal Colectomy for the Treatment of Severe, Complicated Clostridium difficile Associated Disease. Ann. Surg. 2011, 254, 423–427; discussion 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Baseline Characteristics | Total (n = 215) | Monotherapy (n = 115) | Combination Therapy (n = 100) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 106 (49.3) | 66 (57.4) | 40 (40.0) | 0.016 |

| Female | 109 (50.7) | 49 (42.6) | 60 (60.0) | |

| Age, y | 72.0 ± 14.56 | 72.2 ± 14.5 | 71.7 ± 14.5 | 0.812 |

| Hospital characteristics at the time of CDI diagnosis | ||||

| Vital signs (Mean ± SD) | ||||

| Systolic BP | 122.2 ± 19.9 | 124.2 ± 21.4 | 120.0 ± 17.9 | 0.112 |

| Diastolic BP | 68.3 ± 12.0 | 69.6 ± 11.8 | 66.8 ± 12.2 | 0.093 |

| Temperature | 37.1 ± 0.7 | 37.1 ± 0.7 | 37.2 ± 0.7 | 0.682 |

| Heart rate | 89.6 ± 19.0 | 88.4 ± 19.8 | 90.9 ± 18.0 | 0.333 |

| Laboratory results (Mean ± SD) | ||||

| White blood cell count, 109/L | 17.2 ± 11.0 | 16.3 ± 11.5 | 18.4 ± 10.3 | 0.157 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 9.6 ± 1.6 | 9.5 ± 1.7 | 9.8 ± 1.5 | 0.294 |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 106.0 ± 119.6 | 10.4.2 ± 115.1 | 108.1 ± 125.2 | 0.811 |

| BUN, mg/dL | 41.5 ± 28.1 | 41.3 ± 23.6 | 41.7 ± 32.6 | 0.921 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 2.9 ± 2.5 | 3.0 ± 2.5 | 2.8 ± 2.5 | 0.485 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 0.440 |

| Toxin EIA | ||||

| Negative | 18 (15.7) | 14 (14.0) | 0.919 | |

| Positive | 32 (27.8) | 27 (27.0) | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hematologic malignancies | 25 (11.6) | 14 (12.2) | 11 (11.0) | 0.956 |

| Solid cancers | 19 (8.8) | 8 (7.0) | 11 (11.0) | 0.423 |

| Solid organ transplantations | 11 (5.1) | 6 (5.2) | 5 (5.0) | 1.000 |

| Hypertension | 108 (50.2) | 61 (53.0) | 47 (47.0) | 0.455 |

| Coronary artery disease | 18 (8.4) | 13 (11.3) | 5 (5.0) | 0.156 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 80 (37.2) | 41 (35.7) | 39 (39.0) | 0.715 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 8 (3.7) | 6 (5.2) | 2 (2.0) | 0.290 |

| Chronic renal disorders | 99 (46.0) | 60 (50.2) | 39 (39.0) | 0.073 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 45 (20.9) | 25 (21.7) | 20 (20.0) | 0.885 |

| Immunosuppressed | ||||

| Immunosuppressants | 15 (7.0) | 8 (7.0) | 7 (7.0) | 1.000 |

| Corticosteroids | 37 (17.2) | 21 (18.3) | 16 (16.0) | 0.797 |

| ICU admission | 60 (27.9) | 29 (25.2) | 31 (31.0) | 0.940 |

| Antibiotic exposures | 191 (93.6) | 104 (93.7) | 87 (93.5) | 1.000 |

| 60-Day Outcome | Total (n = 215) | Monotherapy (n = 115) | Combination Therapy (n = 100) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Death or colectomy | 55 (25.6) | 29 (25.2) | 26 (26.0) | 1.000 |

| Death | 52 (24.2) | 27 (23.5) | 25 (25.0) | 0.920 |

| Colectomy | 3 (1.4) | 2 (1.7) | 1 (1.0) | 1.000 |

| Clinical cure at Day 10 | 156 (72.6) | 91.1 (79.1) | 65 (65.0) | 0.031 |

| Recurrence | 37 (18.0) | 21 (19.1) | 16 (16.8) | 0.814 |

| Length of stay after CDI diagnosis, days, mean (range) | 26.0 (2–779) | 31.0 (2–779) | 23.0 (3–619) | 0.159 |

| Length of ICU stay after CDI diagnosis, days, mean (range) | 35.0 (3–619) | 35.0 (6–112) | 32.0 (3–619) | 0.988 |

| 60-Day Outcome | Total (n = 91) | Negative (n = 32) | Positive (n = 59) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Death or colectomy | 19 (20.9) | 8 (25.0) | 11 (18.6) | 0.658 |

| Clinical cure at Day 10 | 65 (71.4) | 20 (62.5) | 45 (76.3) | 0.252 |

| Recurrence | 21 (23.1) | 7 (21.9) | 14 (23.7) | 1.000 |

| Length of stay after CDI diagnosis, days, mean (range) | 43.5 (3–358) | 35.2 (5–144) | 47.7 (3–358) | 0.352 |

| Length of ICU stay after CDI diagnosis, days, mean (range) | 37.2 (4–141) | 24.3 (5–86) | 45.1 (4–141) | 0.081 |

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariable Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Treatment | ||||

| Combination | Reference | |||

| Vancomycin | 1.04 (0.56, 1.93) | 0.896 | ||

| Sex (female vs. male) | 1.12 (0.6, 2.06) | 0.727 | ||

| Age, y | ||||

| 18–55 | Reference | |||

| 56–75 | 1.39 (0.13, 14.78) | 0.785 | ||

| ≥76 | 1.33 (0.14, 12.37) | 0.804 | ||

| Vital signs | ||||

| Systolic BP | 0.99 (0.97, 1) | 0.097 | ||

| Diastolic BP | 0.97 (0.95, 1) | 0.057 | ||

| Temperature | 0.91 (0.58, 1.43) | 0.68 | ||

| Heart rate | 1.04 (1.02, 1.05) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory results | ||||

| White blood cell count | 1 (1, 1) | 0.073 | ||

| Hemoglobin | 1 (1, 1) | 0.067 | ||

| Platelet count | 1 (1, 1) | 0.373 | ||

| BUN | 1.02 (1, 1.03) | 0.005 | 1.01 (1, 1.03) | 0.019 |

| Creatinine | 1.02 (0.91, 1.16) | 0.699 | ||

| Albumin | 0.35 (0.18, 0.66) | 0.001 | 0.34 (0.17, 0.7) | 0.003 |

| Toxin EIA positivity | 0.69 (0.24,1.93) | 0.478 | ||

| Hematologic malignancies | 3.82 (1.62, 8.99) | 0.002 | 3.6 (1.36, 9.51) | 0.01 |

| Immunosuppressed | ||||

| Immunosuppressants | 1.06 (0.32, 3.48) | 0.92 | ||

| Corticosteroids | 1.75 (0.82, 3.74) | 0.147 | ||

| Antibiotic exposures | 4.37 (0.55, 34.47) | 0.162 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cho, Y.W.; Moon, J.M.; Lee, H.H.; Kim, J.; Choi, C.H.; Lee, K.-M.; Cho, Y.-S. Combination Therapy with Oral Vancomycin Plus Intravenous Metronidazole Is Not Superior to Oral Vancomycin Alone for the Treatment of Severe Clostridioides difficile Infection: A KASID Multicenter Study. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121252

Cho YW, Moon JM, Lee HH, Kim J, Choi CH, Lee K-M, Cho Y-S. Combination Therapy with Oral Vancomycin Plus Intravenous Metronidazole Is Not Superior to Oral Vancomycin Alone for the Treatment of Severe Clostridioides difficile Infection: A KASID Multicenter Study. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121252

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, Young Wook, Jung Min Moon, Hyeong Han Lee, Jiyoung Kim, Chang Hwan Choi, Kang-Moon Lee, and Young-Seok Cho. 2025. "Combination Therapy with Oral Vancomycin Plus Intravenous Metronidazole Is Not Superior to Oral Vancomycin Alone for the Treatment of Severe Clostridioides difficile Infection: A KASID Multicenter Study" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121252

APA StyleCho, Y. W., Moon, J. M., Lee, H. H., Kim, J., Choi, C. H., Lee, K.-M., & Cho, Y.-S. (2025). Combination Therapy with Oral Vancomycin Plus Intravenous Metronidazole Is Not Superior to Oral Vancomycin Alone for the Treatment of Severe Clostridioides difficile Infection: A KASID Multicenter Study. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121252