The Impact of Antimicrobial Therapy on the Development of Microbiota in Infants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Group I: 30 healthy infants aged 6–12 months, born full-term (38–40 weeks of gestation), delivered vaginally, and who had not received antibiotic therapy.

- Group II: 30 infants aged 6–12 months, born full-term (38–40 weeks of gestation), delivered vaginally, who had received antibiotic therapy with β-lactam antibiotics (penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems). Most children in this group were born at the National Medical Research Center of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Perinatology named after V.I. Kulakov, with five children born in various other medical institutions across Russia.

- In both groups, 16 children in Group I and 14 in Group II were breastfed.

- 14 children in Group I (46.6%) and 16 in Group II (53.3%) were fed artificially (formula-fed).

- 28 children in Group I (93.3%) and 25 in Group II (83.3%) received complementary foods.

- Two children in Group I and five in Group II did not.

2.1. PCR Procedure

2.2. Statistical Analysis and Visualization

2.3. Biodiversity Indices

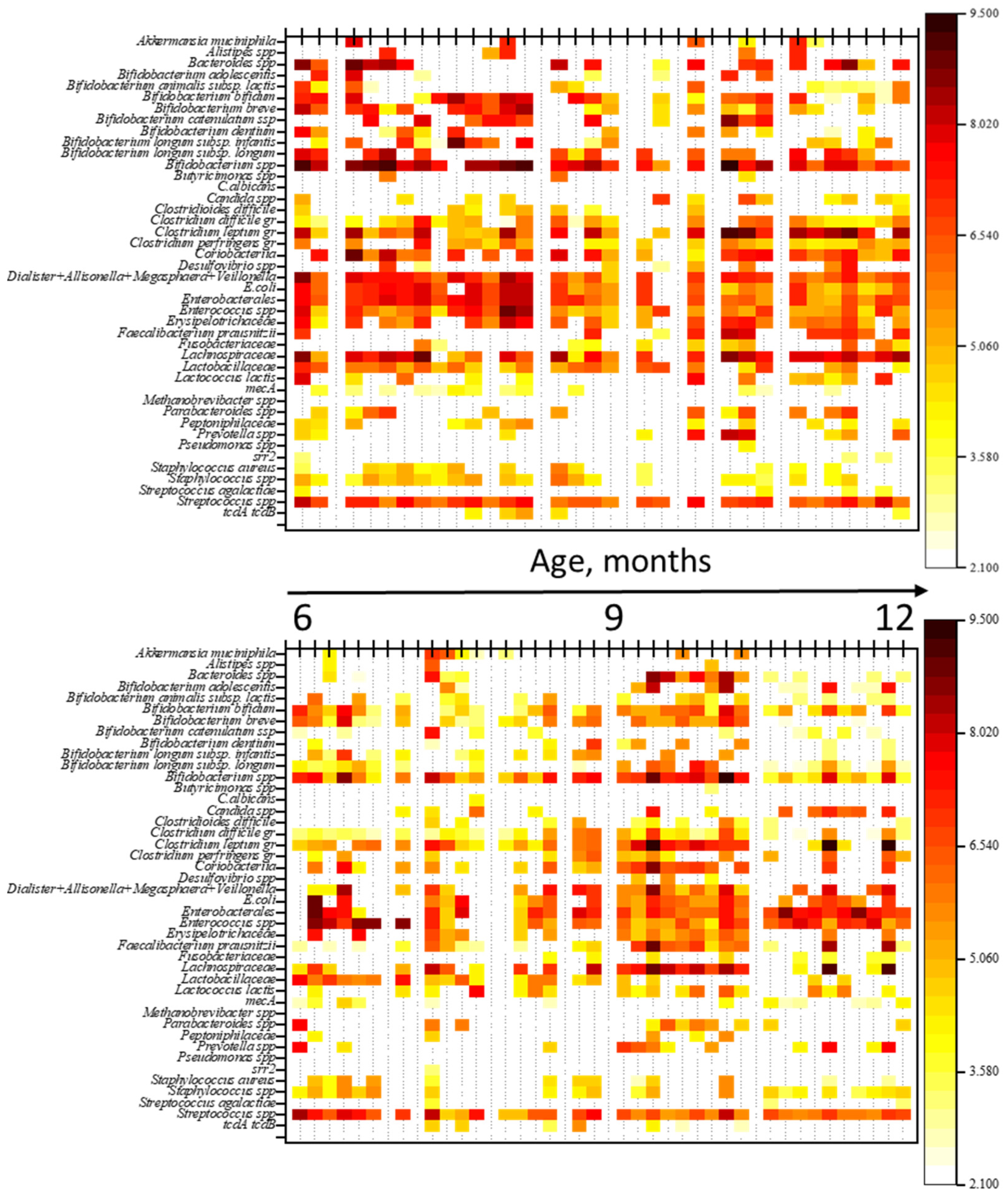

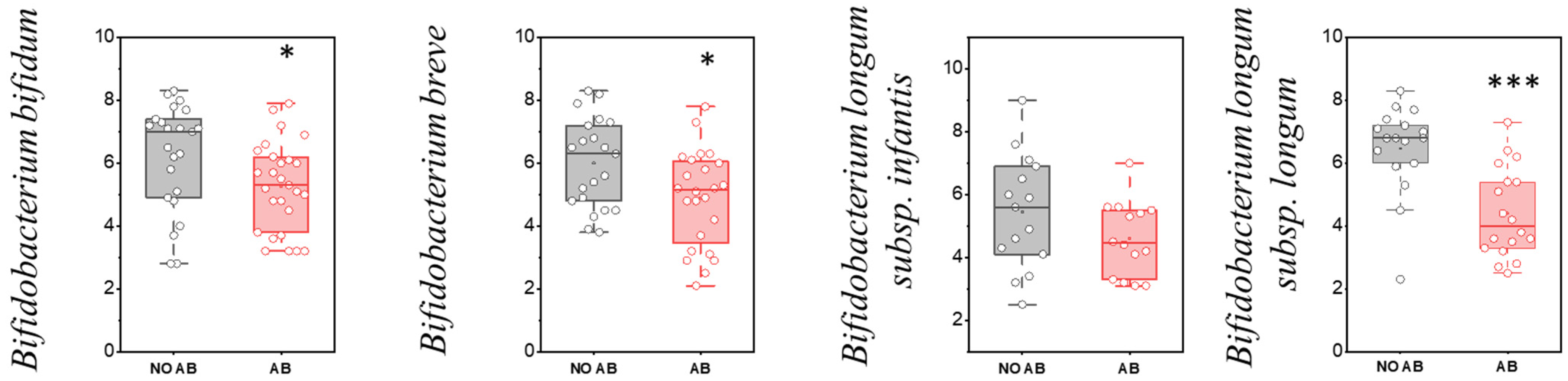

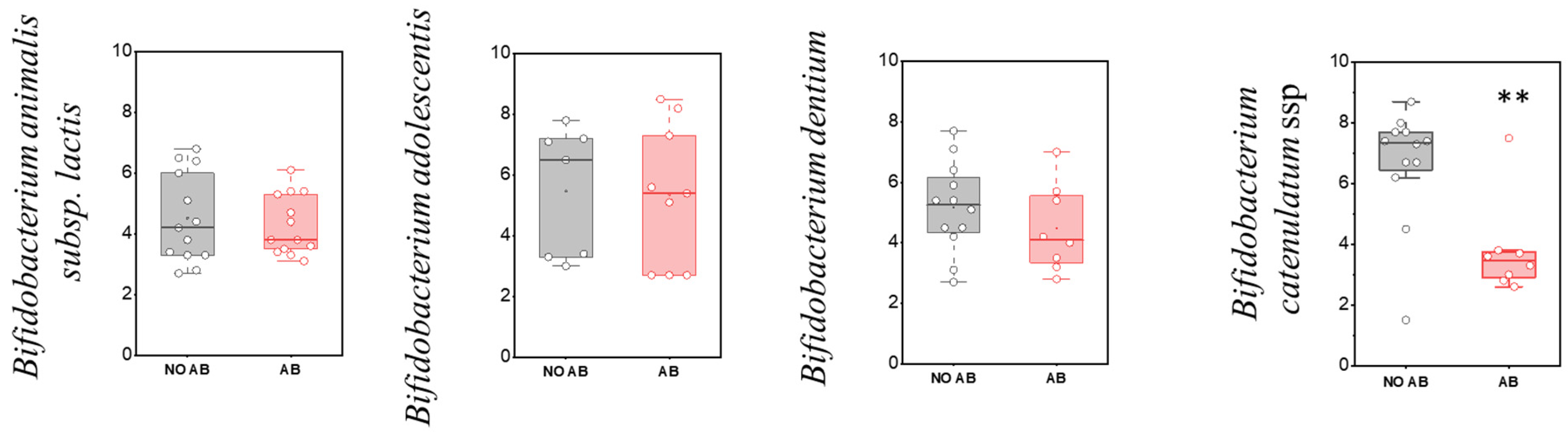

3. Results

Multiple Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AB | antibiotic |

| ABT | antibiotic therapy |

| qPCR | real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| IAP | Intrapartum Antibiotic Prophylaxis |

| GIT | gastrointestinal tract |

| IBD | inflammatory bowel diseases |

| SDI | species diversity |

| SCFA | short-chain fatty acids |

| CDAD | C. difficile-associated disease |

| CDI | Clostridioides difficile infection |

References

- Vrancken, G.; Gregory, A.C.; Huys, G.R.B.; Faust, K.; Raes, J. Synthetic ecology of the human gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda-Ferre, P.; Alcaraz, L.D.; Cabrera-Rubio, R.; Romero, H.; Simón-Soro, A.; Pignatelli, M.; Mira, A. The oral metagenome in health and disease. ISME J. 2012, 6, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodacre, R. Metabolomics of a superorganism. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 259S–266S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelzer, E.; Gomez-Arango, L.F.; Barrett, H.L.; Nitert, M.D. Review: Maternal health and the placental microbiome. Placenta 2017, 54, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Hamady, M.; Fraser-Liggett, C.M.; Knight, R.; Gordon, J.I. The Human Microbiome Project. Nature 2007, 449, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardissone, A.N.; de la Cruz, D.M.; Davis-Richardson, A.G.; Rechcigl, K.T.; Li, N.; Drew, J.C.; Murgas-Torrazza, R.; Sharma, R.; Hudak, M.L.; Triplett, E.W.; et al. Meconium microbiome analysis identifies bacteria correlated with premature birth. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGiulio, D.B.; Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Costello, E.K.; Lyell, D.J.; Robaczewska, A.; Sun, C.L.; Goltsman, D.S.A.; Wong, R.J.; Shaw, G.; et al. Temporal and spatial variation of the human microbiota during pregnancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 11060–11065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moles, L.; Gómez, M.; Heilig, H.; Bustos, G.; Fuentes, S.; de Vos, W.; Fernández, L.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Jiménez, E. Bacterial diversity in meconium of preterm neonates and evolution of their fecal microbiota during the first month of life. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamczak, A.M.; Werblińska, A.; Jamka, M.; Walkowiak, J. Maternal-Foetal/Infant Interactions-Gut Microbiota and Immune Health. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belyaeva, I.A.; Bombardirova, E.P.; Turti, T.V.; Mitish, M.D.; Potekhina, T.V. Intestinal Microbiota in Premature Children—The Modern State of the Problem (Literature Analysis). Pediatr. Pharmacol. 2015, 12, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, R.I.; Sghir, A.; Gaskins, H.R. Developmental microbial ecology of the neonatal gastrointestinal tract. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 1035S–1045S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, L.K.; Samoukina, A.M.; Alekseeva, Y.A.; Fedotova, T.A.; Petrova, O.A.; Strakhova, S.S. Modern View on the Formation of Microbiotes Digestive Tract in Children of the First Year of Life. Mod. Probl. Sci. Educ. 2018, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantoja-Feliciano, I.G.; Clemente, J.C.; Costello, E.K.; Perez, M.E.; Blaser, M.J.; Knight, R.; Dominguez-Bello, M.G. Biphasic assembly of the murine intestinal microbiota during early development. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1112–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grech, A.; Collins, C.E.; Holmes, A.; Lal, R.; Duncanson, K.; Taylor, R.; Gordon, A. Maternal exposures and the infant gut microbiome: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadkhah, A.I.; Simpson, E.B.; Patterson, S.G.; Ferguson, J.F. Development of the Gut Microbiome in Children, and Lifetime Implications for Obesity and Cardiometabolic Disease. Children 2018, 5, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, R.C.; Manges, A.R.; Finlay, B.B.; Prendergast, A.J. The Human Microbiome and Child Growth—First 1000 Days and Beyond. Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aagaard, K.; Stewart, C.J.; Chu, D. Una destinatio, viae diversae: Does exposure to the vaginal microbiota confer health benefits to the infant, and does lack of exposure confer disease risk? EMBO Rep. 2016, 17, 1679–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäckhed, F.; Roswall, J.; Peng, Y.; Feng, Q.; Jia, H.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Li, Y.; Xia, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhong, H.; et al. Dynamics and Stabilization of the Human Gut Microbiome During the First Year of Life. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernikova, D.A.; Madan, J.C.; Housman, M.L.; Zain-ul-abideen, M.; Lundgren, S.N.; Morrison, H.G.; Sogin, M.L.; Williams, S.M.; Moore, J.H.; Karagas, M.R.; et al. The premature infant gut microbiome during the first 6 weeks of life differs based on gestational maturity at birth. Pediatr. Res. 2018, 84, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; Costello, E.K.; Contreras, M.; Magris, M.; Hidalgo, G.; Fierer, N.; Knight, R. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11971–11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.J.; Lynch, D.B.; Murphy, K.; Ulaszewska, M.; Jeffery, I.B.; O’Shea, C.A.; Watkins, C.; Dempsey, E.; Mattivi, F.; Tuohy, K.; et al. Evolution of gut microbiota composition from birth to 24 weeks in the INFANTMET Cohort. Microbiome 2017, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson, H.E.; Abrahamsson, T.R.; Jenmalm, M.C.; Harris, K.; Quince, C.; Jernberg, C.; Björkstén, B.; Engstrand, L.; Andersson, A.F. Decreased gut microbiota diversity, delayed Bacteroidetes colonisation and reduced Th1 responses in infants delivered by Caesarean section. Gut 2014, 63, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.; Blakstad, E.W.; Moltu, S.J.; Strømmen, K.; Nakstad, B.; Rønnestad, A.E.; Brække, K.; Iversen, P.O.; Drevon, C.A.; de Vos, W. Intestinal microbiota development and gestational age in preterm neonates. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouhy, F.; Watkins, C.; Hill, C.J.; O’Shea, C.-A.; Nagle, B.; Dempsey, E.M.; O’Toole, P.W.; Ross, R.P.; Ryan, C.A.; Stanton, C. Perinatal factors affect the gut microbiota up to four years after birth. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priputnevich, T.V.; Isaeva, E.L.; Muravieva, V.V.; Mesyan, M.K.; Zubkov, V.V.; Nikolaeva, A.V.; Bembeeva, B.O.; Timofeeva, L.A.; Kozlova, A.A.; Makarov, V.V.; et al. Development of the gut microbiota of term and late preterm newborn infants. Neonatol. News Opin. Train. 2023, 11, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovtun, A.S.; Averina, O.V.; Angelova, I.Y.; Yunes, R.A.; Zorkina, Y.A.; Morozova, A.Y.; Pavlichenko, A.V.; Syunyakov, T.S.; Karpenko, O.A.; Kostyuk, G.P.; et al. Alterations of the Composition and Neurometabolic Profile of Human Gut Microbiota in Major Depressive Disorder. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Curtis, N. The effect of antibiotics on the composition of the intestinal microbiota—A systematic review. J. Infect. 2019, 79, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, W.E.; Burnham, C.-A.D.; Dantas, G.; Kwon, J.H. The Gut Microbiome as a Reservoir for Antimicrobial Resistance. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 223, S209–S213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarner, F.; Malagelada, J.-R. Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet 2003, 361, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgos, S.; Hibberd, O.; Mullally, P.J.W.; Segura-Retana, R.; Soyer, S.; Hall, D. Don’t Forget the Bubbles Antibiotic Use for Common Infections in Pediatric Emergency Departments: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakuria, B. The Beta Lactam Antibiotics as an Empirical Therapy in a Developing Country: An Update on Their Current Status and Recommendations to Counter the Resistance against Them. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013, 7, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.A. Antimicrobial therapy of pneumonia in infants and children. Semin. Respir. Infect. 1996, 11, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-S.; Zhou, Y.-L.; Bai, G.-N.; Li, S.-X.; Xu, D.; Chen, L.-N.; Chen, X.; Dong, X.-Y.; Fu, H.-M.; Fu, Z.; et al. Expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children. World J. Pediatr. 2024, 20, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thy, M.; Timsit, J.-F.; de Montmollin, E. Aminoglycosides for the Treatment of Severe Infection Due to Resistant Gram-Negative Pathogens. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovtun, A.S.; Averina, O.V.; Alekseeva, M.G.; Danilenko, V.N. Antibiotic Resistance Genes in the Gut Microbiota of Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder as Possible Predictors of the Disease. Microb. Drug Resist. 2020, 26, 1307–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianka, E.R. Evolutionary Ecology; Harper Row: New York, NY, USA; Hagerstown, MD, USA; San Francisco, CA, USA; London, UK, 1978; p. 398. [Google Scholar]

- Schwiertz, A.; Jacobi, M.; Frick, J.-S.; Richter, M.; Rusch, K.; Köhler, H. Microbiota in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J. Pediatr. 2010, 157, 240–244.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 2012, 486, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wexler, A.G.; Goodman, A.L. An insider’s perspective: Bacteroides as a window into the microbiome. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabold, S.; Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and Statistical Modeling with Python. SciPy 2010, 7, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltak, S.N.; Steen, T.Y. The Impact of Antibiotic Use on the Human Gut Microbiome: A Review. Georgian Med. Rev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patangia, D.V.; Anthony Ryan, C.; Dempsey, E.; Paul Ross, R.; Stanton, C. Impact of antibiotics on the human microbiome and consequences for host health. Microbiologyopen 2022, 11, e1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jernberg, C.; Löfmark, S.; Edlund, C.; Jansson, J.K. Long-term impacts of antibiotic exposure on the human intestinal microbiota. Microbiology 2010, 156, 3216–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassour, M.; Vatanen, T.; Siljander, H.; Hämäläinen, A.-M.; Härkönen, T.; Ryhänen, S.J.; Franzosa, E.A.; Vlamakis, H.; Huttenhower, C.; Gevers, D.; et al. Natural history of the infant gut microbiome and impact of antibiotic treatment on bacterial strain diversity and stability. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 343ra81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.; Salonen, A.; Virta, L.J.; Kekkonen, R.A.; Forslund, K.; Bork, P.; de Vos, W.M. Intestinal microbiome is related to lifetime antibiotic use in Finnish pre-school children. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morreale, C.; Giaroni, C.; Baj, A.; Folgori, L.; Barcellini, L.; Dhami, A.; Agosti, M.; Bresesti, I. Effects of Perinatal Antibiotic Exposure and Neonatal Gut Microbiota. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiu, R.; Darby, E.M.; Alcon-Giner, C.; Acuna-Gonzalez, A.; Camargo, A.; Lamberte, L.E.; Phillips, S.; Sim, K.; Shaw, A.G.; Clarke, P.; et al. Impact of early life antibiotic and probiotic treatment on gut microbiome and resistome of very-low-birth-weight preterm infants. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, M.-C.; Stiemsma, L.T.; Amenyogbe, N.; Brown, E.M.; Finlay, B. The Intestinal Microbiome in Early Life: Health and Disease. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversa, Z.; Atkinson, E.J.; Schafer, M.J.; Theiler, R.N.; Rocca, W.A.; Blaser, M.J.; LeBrasseur, N.K. Association of Infant Antibiotic Exposure with Childhood Health Outcomes. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, S.; Thorsen, J.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Chawes, B.; Bønnelykke, K.; Blaser, M.J.; Sevelsted, A.; Stokholm, J. Use of antibiotics in early life and development of diseases in childhood: Nationwide registry study. BMJ Med. 2025, 4, e001064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, Q.A.; Pittet, L.F.; Curtis, N.; Zimmermann, P. Antibiotic exposure and adverse long-term health outcomes in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2022, 85, 213–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, M.A.; Setoguchi, S.; Gerhard, T.; Roy, J.; Koffman, D.; Mendhe, D.; Madej, J.; Strom, B.L.; Blaser, M.J.; Horton, D.B. Early Childhood Antibiotics and Chronic Pediatric Conditions: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 232, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, W.S.W.; Sabu, P.; Deopujari, V.; Levy, S.; Shah, A.A.; Clemency, N.; Provenzano, M.; Saadoon, R.; Munagala, A.; Baker, R.; et al. Prenatal and Peripartum Exposure to Antibiotics and Cesarean Section Delivery Are Associated with Differences in Diversity and Composition of the Infant Meconium Microbiome. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, B.; Jin, Z.; Zhuang, X.; Dai, W.; Yang, Z.; Feng, X.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, Y.; et al. Perinatal Antibiotic Exposure Affects the Transmission between Maternal and Neonatal Microbiota and Is Associated with Early-Onset Sepsis. mSphere 2020, 5, e00984-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajankila, N.; Wala, S.J.; Ragan, M.V.; Volpe, S.G.; Dumbauld, Z.; Purayil, N.; Mihi, B.; Besner, G.E. Current and future methods of probiotic therapy for necrotizing enterocolitis. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1120459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloisio, I.; Quagliariello, A.; De Fanti, S.; Luiselli, D.; De Filippo, C.; Albanese, D.; Corvaglia, L.T.; Faldella, G.; Di Gioia, D. Evaluation of the effects of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis on newborn intestinal microbiota using a sequencing approach targeted to multi hypervariable 16S rDNA regions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 5537–5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogacka, A.; Salazar, N.; Suárez, M.; Milani, C.; Arboleya, S.; Solís, G.; Fernández, N.; Alaez, L.; Hernández-Barranco, A.M.; de los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G.; et al. Impact of intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis upon the intestinal microbiota and the prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes in vaginally delivered full-term neonates. Microbiome 2017, 5, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzola, G.; Murphy, K.; Ross, R.P.; Di Gioia, D.; Biavati, B.; Corvaglia, L.T.; Faldella, G.; Stanton, C. Early Gut Microbiota Perturbations Following Intrapartum Antibiotic Prophylaxis to Prevent Group B Streptococcal Disease. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.; Konya, T.; Persaud, R.; Guttman, D.; Chari, R.; Field, C.; Sears, M.; Mandhane, P.; Turvey, S.; Subbarao, P.; et al. Impact of maternal intrapartum antibiotics, method of birth and breastfeeding on gut microbiota during the first year of life: A prospective cohort study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 123, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Gender | Date of Birth | ABT | Breastfeeding (Yes/No) | Complementary Foods (Yes/No) | Age (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | M | 13 June 2023 | no | No | Yes | 7 |

| F2 | M | 18 June 2023 | no | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| F3 | M | 13 June 2023 | no | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| F9 | F | 18 September 2023 | no | No | Yes | 6 |

| F10 | M | 2 September 2023 | no | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| F11 | F | 23 June 2023 | no | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| F12 | M | 6 May 2023 | no | No | Yes | 11 |

| F13 | F | 5 May 2023 | no | Yes | No | 12 |

| F16 | M | 15 May 2023 | no | No | Yes | 12 |

| F17 | M | 2 October 2023 | no | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| F21 | F | 7 May 2023 | no | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| F23 | F | 5 October 2023 | no | mix | Yes | 7 |

| F24 | F | 28 May 2023 | no | No | Yes | 12 |

| F25 | F | 9 October 2023 | no | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| F29 | F | 9 June 2023 | no | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| F30 | M | 24 June 2023 | no | No | Yes | 11 |

| F31 | F | 13 October 2023 | no | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| F34 | M | 1 June 2023 | no | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| F35 | M | 11 September 2023 | no | Yes | No | 9 |

| F44 | M | 2 January 2024 | no | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| F45 | F | 1 February 2024 | no | No | Yes | 6 |

| F47 | M | 19 December 2023 | no | No | Yes | 8 |

| F48 | F | 30 January 2024 | no | No | Yes | 7 |

| F49 | M | 30 January 2024 | no | No | Yes | 7 |

| F50 | F | 30 January 2024 | no | No | Yes | 7 |

| F51 | F | 10 August 2023 | no | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| F52 | F | 30 January 2024 | no | No | Yes | 7 |

| F56 | M | 2 January 2024 | no | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| F57 | M | 29 October 2023 | no | No | Yes | 10 |

| F59 | F | 29 September 2023 | no | No | Yes | 11 |

| No. | Gender | Date of Birth | ABT | Breastfeeding (Yes/No) | Complementary Foods (Yes/No) | Age (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F4 | M | 17 March 2023 | yes | No | No | 12 |

| F5 | M | 11 September 2023 | yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| F6 | F | 5 May 2023 | yes | Yes | Yes | 11 |

| F7 | M | 23 March 2023 | yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| F8 | M | 3 October 2023 | yes | No | Yes | 6 |

| F14 | F | 5 October 2023 | yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| F15 | M | 12 June 2023 | yes | No | Yes | 11 |

| F18 | F | 29 October 2023 | yes | No | Yes | 6 |

| F19 | M | 21 September 2023 | yes | No | Yes | 8 |

| F20 | M | 6 June 2023 | yes | No | Yes | 11 |

| F22 | M | 11 December 2023 | yes | Yes | No | 6 |

| F26 | M | 14 June 2023 | yes | Yes | Yes | 11 |

| F27 | M | 13 October 2023 | yes | No | Yes | 8 |

| F28 | M | 11 July 2023 | yes | No | No | 10 |

| F32 | F | 1 December 2023 | yes | Yes | No | 6 |

| F33 | F | 4 July 2023 | yes | No | Yes | 11 |

| F36 | M | 12 July 2023 | yes | No | Yes | 11 |

| F37 | F | 25 August 2023 | yes | No | Yes | 10 |

| F38 | M | 26 September 2023 | yes | No | Yes | 8 |

| F39 | M | 19 September 2023 | yes | No | Yes | 9 |

| F41 | F | 31 October 2023 | yes | No | Yes | 8 |

| F42 | F | 22 September 2023 | yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| F43 | M | 5 November 2023 | yes | No | Yes | 8 |

| F46 | M | 12 September 2023 | yes | Yes | Yes | 11 |

| F53 | M | 20 November 2023 | yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| F54 | M | 19 March 2024 | yes | Yes | No | 6 |

| F55 | M | 12 September 2023 | yes | No | Yes | 12 |

| F58 | M | 26 November 2023 | yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| F60 | M | 2 October 2023 | yes | Yes | Yes | 11 |

| F61 | M | 6 September 2023 | yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| Indexes Alpha Diversity | Formula |

|---|---|

| Simpson | S = Σ (ni/N)2 |

| Shannon | H’ = −Σ (pi × ln pi) |

| Microorganisms | NO AB (n = 30) | Frequency (%) | AAB (n = 30) | Frequency (%) | Chi-Square (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bifidobacterium bifidum | 23 | 76.7 | 27 | 90.0 | p > 0.05 |

| Bifidobacterium breve | 21 | 70.0 | 24 | 80.0 | p > 0.05 |

| Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis | 15 | 50.0 | 14 | 46.7 | p > 0.05 |

| Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum | 17 | 56.7 | 18 | 60.0 | p > 0.05 |

| Microorganisms | NO AB Group (n = 30) | Frequency (%) | AB Group (n = 30) | Frequency (%) | Chi-Square (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis | 7 | 23.3 | 9 | 30.0 | p > 0.05 |

| Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis | 13 | 43.3 | 13 | 43.3 | p > 0.05 |

| Bifidobacterium catenulatum ssp. | 12 | 40.0 | 8 | 26.7 | p > 0.05 |

| Bifidobacterium dentium | 12 | 40.0 | 8 | 26.7 | p > 0.05 |

| Microorganisms | NO AB (n = 30) | Frequency (%) | AB (n = 30) | Frequency (%) | Chi-Square (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clostridium leptum gr | 26 | 86.7 | 26 | 86.7 | p > 0.05 |

| Dialister + Allisonella + Megasphaera + Veillonella ** | 29 | 96.7 | 20 | 66.7 | 0.003 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 30 | 100.0 | 26 | 86.7 | p > 0.05 |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii * | 12 | 40.0 | 22 | 73.3 | 0.010 |

| Lachnospiraceae * | 27 | 90.0 | 20 | 66.7 | 0.029 |

| Lactobacillaceae | 24 | 80.0 | 19 | 63.3 | p > 0.05 |

| Lactococcus lactis | 12 | 40.0 | 15 | 50.0 | p > 0.05 |

| Microorganisms | 6–8 Months (n = 30) | Frequency (%) | 9–12 Months (n = 30) | Frequency (%) | Chi-Square (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F. prausnitzii NO AB | 9 | 30 | 13 | 43.3 | p > 0.05 |

| F. prausnitzii AB | 3 | 10 | 9 | 30 | p = 0.053 |

| Microorganisms | NO AB (n = 30) | Frequency (%) | AB (n = 30) | Frequency (%) | Chi-Square (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alistipes spp. | 5 | 16.7 | 3 | 10.0 | p > 0.05 |

| Bacteroides spp. | 17 | 56.7 | 13 | 43.3 | p > 0.05 |

| Butyricimonas spp. | 3 | 10.0 | 1 | 3.3 | p > 0.05 |

| Parabacteroides spp. | 12 | 40.0 | 9 | 30.0 | p > 0.05 |

| Prevotella spp. | 10 | 33.3 | 10 | 33.3 | p > 0.05 |

| Microorganisms | NO AB Group (n = 30) | Frequency (%) | AB Group (n = 30) | Frequency (%) | Chi-Square (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clostridium difficile gr | 25 | 83.3 | 27 | 90.0 | p > 0.05 |

| Clostridium perfringens gr * | 22 | 73.3 | 13 | 43.3 | 0.019 |

| E. coli * | 28 | 93.3 | 20 | 66.7 | 0.010 |

| Enterobacterales | 29 | 96.7 | 25 | 83.3 | p > 0.05 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 30 | 100.0 | 26 | 86.7 | p > 0.05 |

| Erysipelotrichaceae * | 24 | 80.0 | 16 | 53.3 | 0.029 |

| Fusobacteriaceae | 11 | 36.7 | 6 | 20.0 | p > 0.05 |

| Peptoniphilaceae * | 12 | 40.0 | 5 | 16.7 | 0.045 |

| Prevotella spp. | 10 | 33.3 | 10 | 33.3 | p > 0.05 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 1 | 3.3 | 0 | 0.0 | p > 0.05 |

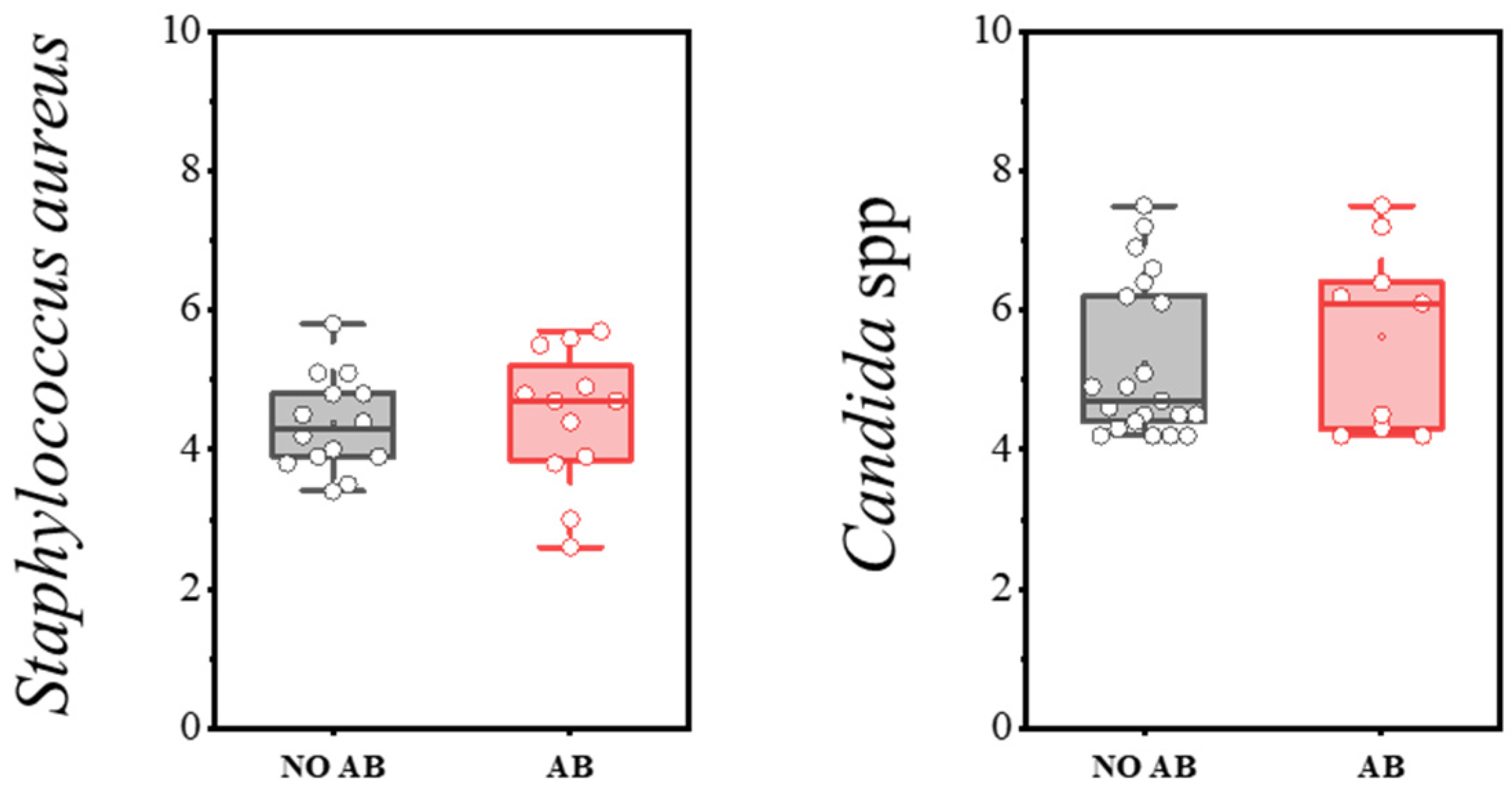

| Microorganisms | NO AB Group (n = 30) | Frequency (%) | AB Group (n = 30) | Frequency (%) | Chi-Square (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | 14 | 47.0 | 12 | 40.0 | p > 0.05 |

| Candida spp. | 12 | 40.0 | 9 | 30.0 | p > 0.05 |

| Variable | Coef | Std.Err | p-Value | Conf_Lower | Conf_Upper | Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABT | −1.7908 | 0.9149 | 0.0552 | −3.6229 | 0.0413 | Bacteroides spp. |

| ABT | −1.5180 | 0.3502 | 0.0001 | −2.2193 | −0.8166 | Bifidobacterium spp. |

| ABT | −2.4733 | 0.6541 | 0.0004 | −3.7831 | −1.1635 | Dialister Allisonella Megasphaera Veillonella |

| ABT | −1.6585 | 0.7901 | 0.0402 | −3.2406 | −0.0764 | Coriobacteriia |

| ABT | −2.0327 | 0.8016 | 0.0140 | −3.6379 | −0.4276 | Lachnospiraceae |

| ABT | −1.7854 | 0.7157 | 0.0155 | −3.2186 | −0.3523 | Bifidobacterium catenulatum ssp. |

| ABT | −2.0162 | 0.7346 | 0.0081 | −3.4873 | −0.5451 | Erysipelotrichaceae |

| ABT | −1.8441 | 0.6830 | 0.0091 | −3.2118 | −0.4764 | E. coli |

| ABT | −1.2229 | 0.4985 | 0.0172 | −2.2211 | −0.2246 | Peptoniphilaceae |

| ABT | −1.5782 | 0.6544 | 0.0191 | −2.8885 | −0.2679 | Clostridium perfringens gr |

| Breastfeeding | −1.6220 | 0.7758 | 0.0410 | −3.1755 | −0.0686 | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii |

| Breastfeeding | −1.8040 | 0.5781 | 0.0028 | −2.9617 | −0.6464 | Akkermansia muciniphila |

| Breastfeeding | −1.2088 | 0.6878 | 0.0842 | −2.5860 | 0.1685 | Clostridium leptum gr |

| Breastfeeding | −1.3544 | 0.7161 | 0.0637 | −2.7883 | 0.0795 | Bifidobacterium catenulatum ssp. |

| Breastfeeding | −1.7622 | 0.4988 | 0.0008 | −2.7610 | −0.7634 | Peptoniphilaceae |

| Breastfeeding | −1.6065 | 0.6861 | 0.0227 | −2.9803 | −0.2327 | Bifidobacterium breve |

| Breastfeeding | −0.5169 | 0.2894 | 0.0794 | −1.0963 | 0.0626 | Streptococcus agalactiae |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Priputnevich, T.; Denisov, P.; Zhigalova, K.; Muravieva, V.; Shabanova, N.; Gordeev, A.; Zubkov, V.; Bembeeva, B.; Isaeva, E.; Nikolaeva, A.; et al. The Impact of Antimicrobial Therapy on the Development of Microbiota in Infants. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1245. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121245

Priputnevich T, Denisov P, Zhigalova K, Muravieva V, Shabanova N, Gordeev A, Zubkov V, Bembeeva B, Isaeva E, Nikolaeva A, et al. The Impact of Antimicrobial Therapy on the Development of Microbiota in Infants. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1245. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121245

Chicago/Turabian StylePriputnevich, Tatiana, Pavel Denisov, Ksenia Zhigalova, Vera Muravieva, Natalia Shabanova, Alexey Gordeev, Viktor Zubkov, Bayr Bembeeva, Elena Isaeva, Anastasia Nikolaeva, and et al. 2025. "The Impact of Antimicrobial Therapy on the Development of Microbiota in Infants" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1245. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121245

APA StylePriputnevich, T., Denisov, P., Zhigalova, K., Muravieva, V., Shabanova, N., Gordeev, A., Zubkov, V., Bembeeva, B., Isaeva, E., Nikolaeva, A., & Sukhikh, G. (2025). The Impact of Antimicrobial Therapy on the Development of Microbiota in Infants. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1245. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121245