A Comprehensive Review of the Application of Bacteriophages Against Enteric Bacterial Infection in Poultry: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Prospects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background of Bacteriophages

3. Life Cycle of Bacteriophages

3.1. Lytic Cycle

3.2. Lysogenic Cycle

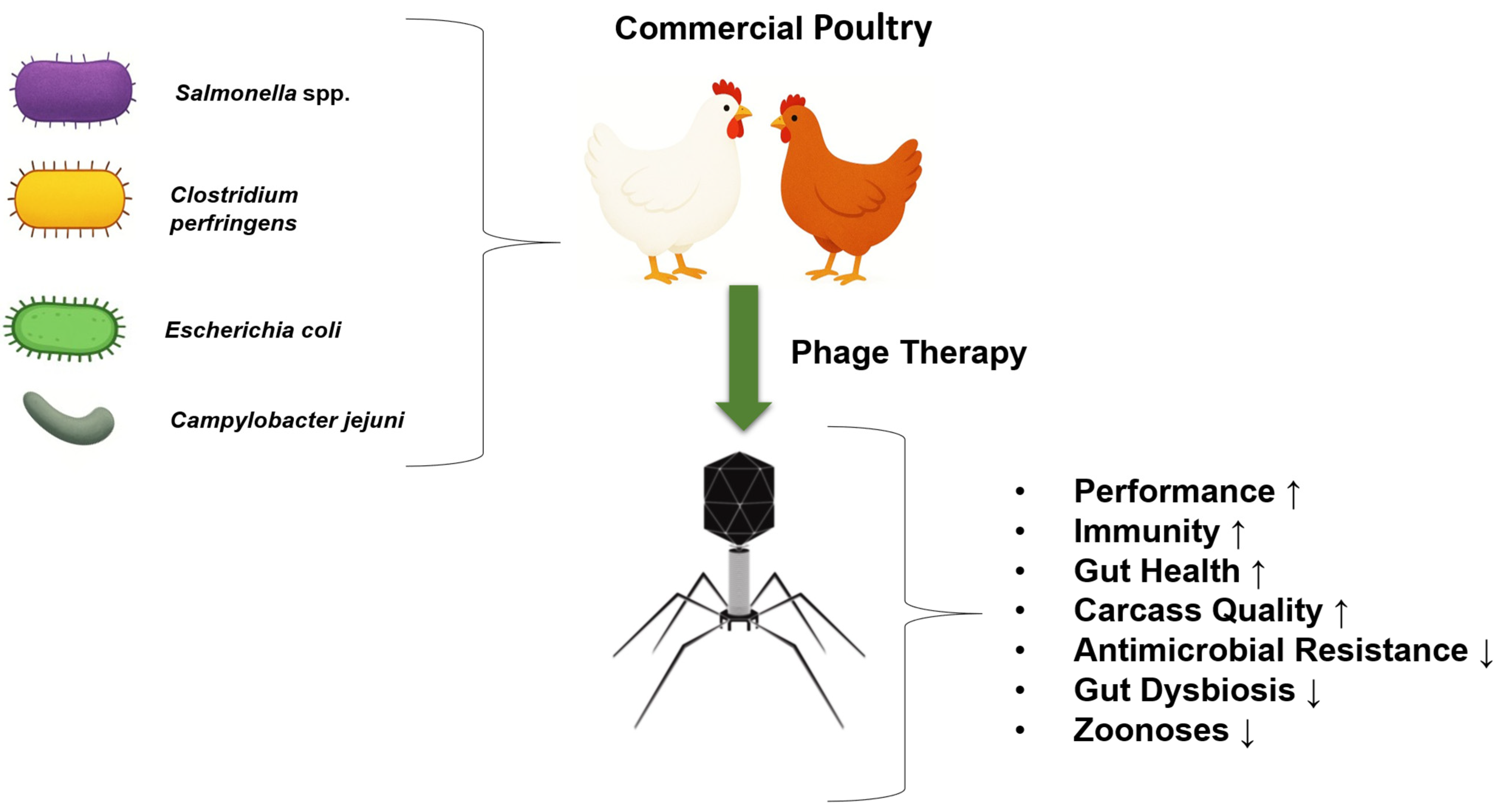

4. Applications of Bacteriophages in the Poultry Industry

4.1. Use of Phages as Feed Additives in Commercial Poultry

4.2. Bacteriophages—Emerging Antibacterial Agents in Poultry Farming

4.2.1. Influence of Bacteriophage Use on Microbial Load

| Targeted Bacteria | Phage | Dose and Route | Main Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campylobacter | Phage Mixture Fletchervirus phage NCTC 12673 + Firehammervirus phage vB_CcM-LmqsCPL1/1 | Phage Mixture: 8.94 × 106 PFU per bird via drinking water | Using a phage mixture reduced Campylobacter load in fecal samples by up to 1.1 log10 CFU/mL compared to the infected control | [64] |

| Salmonella (S. typhimurium and S. enteritidis) | BP cocktail (Belonging to the Myoviridae family) | 106 PFU/g of feed | At 7, 14, and 21 days, the application of the BP cocktail showed a significant reduction in Salmonella colonization in the broilers’ liver, crop, spleen, and caeca | [65] |

| E. coli, Clostridium perfringens | E. coli phage cocktail | Doses 1 g/kg, and 2 g/kg via feed Concentration 1010 PFU/g | C. perfringens in the ileum decreased (p < 0.05) by adding 1 g/kg phage cocktail and 1 g/kg probiotic | [66] |

| Salmonella enteritidis | Bacteriophage cocktail/BC containing G3D03, L1R06, and L1N01 | 109 PFU/mL oral administration | In comparison to the infected control group, the data showed that BC supplementation lowered bacterial concentrations in the liver, spleen, heart, and cecum | [67] |

| Salmonella enteritidis | Commercial BP (ProBe-Bac®) | 1 g/kg and 1.5 g/kg via diet | At 7- and 14-day post-challenge, BP supplementation significantly (p < 0.05) decreased S. enteritidis and coliform bacteria count in the cecum of chickens in comparison to the infected untreated group | [68] |

| Salmonella enteritidis | UPWr_S134 phage cocktail | Dose 3 × 1010 PFU/mL inoculated orally Concentration 1 × 107 PFU/mL | Phage treatment dramatically reduced the number of S. enteritidis in internal organs (such as the liver, spleen, and cecal tonsils) compared to the infected untreated group | [69] |

| Salmonella typhimurium | Phage cocktail (SPFM10 and SPFM14) | Three doses 1 × 105, 0.1 × 106, and 10 × 107 PFU/kg/day/chicken via feed Concentration 3 × 1011 PFU/L | Phage treatment significantly (p < 0.05) decreased Salmonella colonization and its counts in feces compared to the infected untreated group | [70] |

| Proteobacteria (E. coli, Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonella typhimurium) | Bacteriophage Cocktail (Bacter Phage C) (CTCBIO Inc., Seoul, Korea) | 500 ppm via diet | BP supplementation in combination with β-mannanases decreased Proteobacteria and increased Bacteroidetes in the cecum | [71] |

| Clostridium perfringens | Powdered and encapsulated BP | 106 PFU/g of diet | Dietary BP supplementation significantly (p < 0.05) decreased cecal C. perfringens counts compared to the infected control group | [72] |

| Escherichia coli | E. coli O78 bacteriophage | 108 PFU/mL intratracheally | When compared to the infected non-treated group, BP treatment resulted in a significantly lower E. coli numbers in the lungs | [73] |

| Salmonella | Phage cocktail (SK-E1, SK-Ti1 SK-T2) | 1 mL of 108 PFU/mL (drinkers) and 1 mL of 107 PFU/mL (Shavings) | Salmonella counts in drinking water were lowered by the phage cocktail by up to 2.80 log10 units, and in shavings, by up to 2.30 log10 units | [74] |

| S. enteritidis | Phage cocktail, UPWr_S134, | 1 × 107 PFU/mL via drinking water | In experimentally challenged chickens, the phage cocktail significantly reduced the count of Salmonella | [75] |

| Salmonella spp. E. coli; C. perfringens | Commercial Bacteriophage Product (CJ Cheiljedang Corp; Seoul, South Korea) contained mixture of phages targeting Salmonella spp. E. coli; C. perfringens | 0.5 g/kg, 1.0 g/kg via feed Concentration 1 × 108 PFU/g (For each of the Salmonella and E. coli) and 1 × 106 PFU/g (For C. perfringens) | BP Supplementation increased Lactobacillus count in excreta and ileum compared to the group supplemented with antibiotics, while Salmonella and C. perfringens numbers were comparable in BP and antibiotic-supplemented groups | [76] |

| Campylobacter jejuni | Φ16-izsam Φ7-izsam | Φ16-izsam 108 PFU/mL via oral gavage Φ7-izsam 107 PFU/mL, via oral gavage | In comparison to the infected unsupplemented group, the BP supplementation of Φ16-izsam and Φ16-izsam significantly decreased Campylobacter counts to 1 log10 CFU/g and 2 log10 CFU/g, respectively, in the cecum | [77] |

| Clostridium perfringens | φCJ22 | 105, 106, and 107 PFU/kg of diet | Phage inclusion at 106 and 107 decreased (p < 0.05) C. perfringens counts in the cecum (up to 1.24 log), relative to the challenged control group | [78] |

| Clostridium perfringens | Podovirus C. perfringens phage | Dose 0.5 mL via oral gavage Concentration 109 PFU/mL | Phage treatment reduced the cecal C. perfringens counts compared to the infected control group | [79] |

| E. coli,

Salmonella | Bacteriophage cocktail (S. gallinarum, S. typhimurium, S. enteritidis) | Doses 0.25 g BP/Kg, 0.5 gBP/Kg via feed Concentration 108 PFU/g | The supplementation of BP significantly (p < 0.0001) decreased cecal E. coli and Salmonella counts compared with the control group fed only a basal diet | [80] |

| E. coli (Strain E28) | Phage cocktail 1-Six-phage trial [Phages AB27, TB49, G28, TriM, KRA2, and EW2] 2-Four-phage trial [Phages AB27, TB49, G28, and EW2] | log10 4.6 PFU/mL (Six phage) log10 6.7 PFU/mL (four phage) drinking water | In comparison to the infected control group, the number of E. coli bacteria in the feces of birds supplemented with four and six phages was reduced (p < 0.0001) and demonstrated a 0.7 log unit drop | [81] |

| Campylobacter (C. jejuni NCTC 12662, C. jejuni NC3142, and C. coli NC2934) | Phage cocktail (4 phage cocktail consisting of PH5, PH8, PH11, PH13 and 2 Phage Cocktail consisting of PH18, PH19) | 3 mL of 107 PFU/mL via drinking water | In comparison to the non-supplemented control group, phage administration significantly decreased the amount of Campylobacter in the ceca (range 1–3 log10 CFU/g) | [82] |

| Salmonella enteritidis | Bacteriophage from CTCBIO Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea, consisting of a lytic bacteriophage specifically targeting S. enteritidis (KCTC 12012BP) | Doses 1 kg BP/metric ton 1.5 kg BP/metric ton Via feed Concentration 108 PFU/g | Both BP treatments decreased (p < 0.001) the number of S. enteritidis in the ceca and cloacal swabs | [83] |

| Salmonella Kentucky and E. coli | S. Kentucky and E. coli O119 bacteriophages | S. Kentucky BP 0.1 mL orally Concentration 108 PFU/mL E. coli O119 BP Dose 0.1 mL orally Concentration 102 PFU/mL | Phage therapy significantly (p < 0.05) decreased S. Kentucky and E. coli O119 levels in the cecum and liver when compared to the infected control group | [84] |

| Salmonella typhimurium | STP4-a | 109 PFU/g via feed | Pre-administration of phage STP4-a in the feed resulted in undetectable (p < 0.05) Salmonella numbers in feces compared to the infected control group | [85] |

| Salmonella (non-typhoid) | Phage cocktail (SalmoFREE®) | 1 × 108 PFU/mL in drinking water | Phage treatment reduced Salmonella incidence up to 100% compared to the untreated control group | [86] |

| E. coli (APEC O78) | APEC O78-specific bacteriophage | 108 PFU (Intratracheal inoculation) | In comparison to the untreated, uninfected control group, bacteriophage treatment significantly decreased E. coli shedding in the infected group | [87] |

| S. enteritidis | Lytic Bacteriophages (LBs) | 109 PFU/mL via drinking water | Phage therapy showed a significant reduction of up to 1.08 log10 CFU/g in the average number of intestinal S. enteritidis compared with the infected control group | [88] |

| S. typhimurium, S. enteritidis | Bacteriophage (Specific Lytic Phage against S. typhimurium, and S. enteritidis) | 1-S. typhimurium BP/chick 0.1 mL orally Concentration 1.18 × 1011 PFU/mL 2-S. enteritidis BP/chick 0.1 mL orally Concentration 1.03 × 1012 PFU/mL | Infected birds treated with bacteriophage resulted in no Salmonella colonization in the caecum at the end of the experiment | [89] |

| S. enteritidis | Bacteriophage commercial product containing 2 bacteriophages SP-1 and STP-1 | 0.1% BP and 0.2% BP via diet | Supplementation of BP at 0.2% significantly (p < 0.05) reduced nalidixic acid-resistant S. enteritidis numbers in the caecum, spleen, ovary, and feces compared to the infected control | [90] |

| Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) | Naked phage [ΦKAZ14], and Chitosan nanoparticles loaded phage [C-ΦKAZ14 NPs] | Dose 0.2 mL orally Concentration 107 PFU/mL | Chitosan nanoparticles loaded bacteriophage (ΦKAZ14) treatment significantly reduced E. coli count in feces, lungs, and spleen compared to the naked phage ΦKAZ14-treated group and the untreated infected control | [91] |

| S. enteritidis | PSE phage | 106 PFU/mL via oral gavage | BP administration significantly increased lactic acid bacteria count and decreased colibacilli and total aerobes count in the ileum compared to infected and uninfected controls. Prophylactic administration of BP reduced S. enteritidis more effectively in cecal tonsils compared to infected and therapeutic phage-supplemented groups (20% vs. 100%) | [92] |

| Salmonella spp. | Commercial Bacteriophage product (From CTCBIO Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) containing a mixture of BP designed to lyse several key Salmonella serovars and S. aureus | Doses 0.4 g/kg BP 0.8 g/kg BP via feed Concentration 108 PFU per g | BP supplementation significantly decreased caecal Salmonella species compared to the group fed a basal diet only | [93] |

| Salmonella spp. and Clostridium perfringens | Commercial Bacteriophage product (From CTCBIO Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) containing a mixture of individual BP targeting Salmonella spp. and C. perfringens | Dose 0.5 g/kg via diet Concentration 108 PFU per g and 106 PFU per g | BP addition in the diet lowered (p < 0.05) DNA copy numbers of C. perfringens compared to the negative control group who was fed a basal diet only | [94] |

| Salmonella enteritidis | Bacteriophage P22 | 109 PFU/mL via oral gavage | Broilers challenged with Salmonella enteritidis and treated with P22 reduced the Salmonella enteritidis counts in the caeca and crop to less than the detection limit of 102 CFU/g | [95] |

| Campylobacter jejuni | Phage cocktail (Phages 1, 2, 5, and 13 from British Campylobacter phage typing scheme) | 107 PFU per ml via crop | Treatment with phage cocktail and single phage significantly reduced Campylobacter load in the caecum up to log10 2.8 CFU/g | [96] |

| E. coli and Salmonella | Bacteriophage containing S. gallinarum, S. typhimurium, and S. enteritidis at the ratio of 3:3:4. | Doses 0.25 g/kg feed 0.5 g/kg feed Concentration 108 PFU per gram | BP supplementation significantly (p < 0.05) reduced E. coli and Salmonella counts in excreta while increasing Lactobacillus counts compared to the negative control group fed only a basal diet and the antibiotic-supplemented positive control group, respectively | [97] |

| Salmonella enteritidis | Anti-SE bacteriophage | Doses 0.05, 0.1, and 0.2% via feed Concentration 109 PFU/g | Anti-SE bacteriophage supplementation significantly reduced S. enteritidis concentration in the caecum in comparison to the control group fed only a basal diet | [98] |

| Salmonella enteritidis | Bacteriophage ΦCJ07 | 109 PFU/g 107 PFU/g 105 PFU/g via feed | BP supplementation at 109 PFU/g and 107 PFU/g showed significantly (p < 0.05) lower mean intestinal S. enteritidis counts in the challenged and contact birds compared to the infected untreated control | [99] |

| Salmonella spp. and E. coli | Bacteriophages used (S. gallinarum BP, S. typhimurium BP, and S. enteritidis BP) | Doses 0.020% 0.035% 0.050% via feed Concentration 108 PFU per gram | In comparison to the control group that was given only basal feed, bacteriophage supplementation significantly decreased the concentrations of Salmonella spp. and E. coli in the excreta | [100] |

| S. typhimurium | Phage cocktail (UAB_Phi20, UAB_Phi78, and UAB_Phi87) | 1011 PFU/mL via oral gavage | Birds challenged with S. typhimurium and treated with phage cocktail showed reductions (p < 0.0001) in the Salmonella concentrations in the cecum by days 2, 6, and 8 postinfection (4.4 log10, 3.2 log10, and 2 log10, respectively), and at the end of the experiment | [101] |

| Salmonella gallinarum | Bacteriophage CJø01 | 106 PFU/kg via feed | Bacteriophage supplementation in contact birds (birds placed in the same cage with orally challenged S. gallinarum birds) decreased S. gallinarum invasion in the liver, spleen, and caecum compared to the untreated contact birds | [102] |

| Campylobacter jejuni Campylobacter coli | Phage CP220 | The phage doses were 5, 7, and 9 log PFU administered in 1 mL of 30% (wt/vol) CaCO3 by oral gavage | When compared to the uninfected and infected controls, treatment with 7 and 9 log PFU of phage CP220 significantly reduced the mean cecal counts of C. jejuni and C. coli, respectively | [103] |

| Salmonella enteritidis | Bacteriophage cocktail (BP1, BP2, and BP3) | 108 PFU/mL administered via coarse spray and drinking water | Chickens challenged with S. enteritidis and treated with BP showed significantly lower intestinal S. enteritidis numbers than the infected control | [104] |

| Salmonella (S. enteritidis, and S. typhimurium) | Three bacteriophages (Φ151, Φ25, Φ10) | Lower Phage Titer 1 mL of 9 log10 PFU/mL Higher Phage Titer 1 mL of 11.0 log10 PFU/mL via oral gavage | Broilers challenged with Salmonella and treated with a high phage titer showed a significant reduction in cecal colonization by S. enterica serotypes Enteritidis and Typhimurium compared to the infected control | [105] |

| Salmonella enteritidis | Phage cocktail (CB4φ, wt45φ) | 108 PFU/mL chick via oral gavage | After 24 h, birds challenged with SE and treated with a phage cocktail had significantly lower SE load in cecal tonsils than the infected control | [106] |

| Campylobacter jejuni (HPC5 and GIIC8) | Bacteriophages (CP8 and CP34) | Doses log10 5, 7, and 9 PFU were administered in 1 mL of 30% (wt/vol) CaCO3 via oral gavage | Treatment of C. jejuni HPC5-colonized chickens with phage CP34 at varying dosages led to a significant reduction in intestinal Campylobacter counts compared to the untreated control. Similarly, birds infected with C. jejuni GIIC8 and treated with phage CP8 at a dose of log10 7 PFU had significantly lower cecal Campylobacter counts | [107] |

| Campylobacter jejuni | Phage 71 (NCTC 12671) and Phage 69 (NCTC 12669) | Phage 71 doses in PFU/mL 4 × 1011 2 × 1010 5 × 1010 4 × 1010 oral gavage Phage 69 doses in PFU/mL 3 × 1010 5 × 1010 2 × 1010 2 × 1010 | Birds challenged with C. jejuni and given phage 71 and 69 (4-day post-treatment) decreased C. jejuni colonization in the caecum by 1 log10 CFU/g than the infected control | [108] |

| Salmonella typhimurium | Phage cocktail (S2a, S9, and S11) | Dose 0.5 mL/bird orally Concentration 5.4 × 106 PFU | Broilers challenged with ST and treated with phage cocktail showed significantly lower ST counts in the ileum compared to the infected control group (1.1 CFU/mL vs. 81.8 CFU/mL) | [109] |

4.2.2. Effects on Production Parameters of Poultry

| Targeted Bacteria | Phage | Dose and Route | Main Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli, Clostridium perfringens | E. coli phage cocktail | Dose 1 g/kg, and 2 g/kg feed Concentration 1010 PFU/g | Supplementation of phage cocktail and probiotic, both alone or in combination, significantly improved FCR, relative thymus weight, and relative heart weight compared to the infected control group | [66] |

| Salmonella infantis | Autophages phages | 108 PFU/mL via spray | Phage application reduced Salmonella positivity from 100% to 36% in the flock | [110] |

| Salmonella | Salmonella-specific phage cocktail (SPC) SP 75 SP 100 SP 175 | 0.075 g/kg, 0.1 g/kg and 0.175 g/kg via feed | The addition of SPC in the feed significantly (p < 0.05) improved FI and breast weight when compared to the negative control group fed only the basal diet | [111] |

| Salmonella enteritidis | Bacteriophage cocktail (BC) containing G3D03, L1R06, and L1N01 | 109 PFU/mL oral administration | Supplementing BC decreased the mortality rate and improved the BWG of chicks compared to the infected control group | [67] |

| Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli | E. coli phage CE1 | 0.1 mL of 108 PFU/mL Intramuscular injection | Treatment with phage resulted in no mortality in the challenged chickens and was found to be effective in treating colibacillosis | [112] |

| Salmonella spp. (Nontyphoid) | Phage cocktail SPFM10 SPFM14 | Three doses 1 × 105, 0.1 × 106, and 10 × 107 PFU/kg/day/chicken via feed Concentration 3 × 1011 PFU/L | Phage treatment at all three doses in the challenged birds increased BWG, FI, and decreased mortality % in comparison to the challenged birds with no phage in their diet | [70] |

| Nalidixic acid-resistant Salmonella enteritidis | Commercial BP Product from CTCBIO Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea, consisting of a lytic bacteriophage specifically targeting S. enteritidis (KCTC 12012BP) | 108 PFU/g via diet | BP supplementation significantly improved adjusted FCR compared to the infected control group | [83] |

| Clostridium perfringens | Powdered and encapsulated BP | 106 PFU/g of diet | The addition of BP to the diet improved FI, BWG, and FCR compared to the non-supplemented group, and BP-fed groups showed the highest cecal short-chain fatty acids compared to uninfected and infected control groups | [72] |

| Escherichia coli | E. coli O78 bacteriophage | 108 PFU intratracheally | The bacteriophage application in the challenged group significantly increased BW, BWG, and improved FCR compared to the infected–antibiotic-treated group | [73] |

| Salmonella spp; E. coli; Clostridium perfringens | Commercial BP Product (CJ Cheiljedang Corp; Seoul, South Korea) contained mixture of phages targeting Salmonella spp. E. coli; C. perfringens | 0.5 g/kg and 1.0 g/kg Via feed Concentration 1 × 108 PFU/g (For each of the Salmonella and E. coli) and 1 × 106 PFU/g (For C. perfringens) | Throughout the experiment, the BP supplementation significantly increased BWG in comparison to the control group who was fed a basal diet | [76] |

| Clostridium perfringens | Podovirus C. perfringens phage | Dose 0.5 mL via oral gavage Concentration 109 PFU/ml | Phage treatment led to a significant reduction in mortality relative to the infected control | [79] |

| Clostridium perfringens | φCJ22 | 105, 106, and 107 PFU/kg of diet | Compensated FI, BWG, and FCR relative to the challenged control after disease challenge Decreased mortality rates (p < 0.05) | [78] |

| E. coli; Salmonella | Bacteriophage cocktail (S. gallinarum, S. typhimurium, S. enteritidis) | Doses 0.25 g BP/Kg, 0.5 g BP/Kg via feed Concentration 108 PFU/g | BP used at 0.5 g/kg significantly increased BWG compared to the control group fed only a basal diet | [80] |

| Salmonella and E. coli | S. Kentucky and E. coli O119 bacteriophages | S. Kentucky BP 0.1 mL orally Concentration 108 PFU/mL E. coli O119 BP 0.1 mL orally Concentration 102 PFU/mL | Broilers challenged with S. Kentucky and E. coli O119 and treated with phage showed no mortality compared to the infected control (30% mortality) | [84] |

| E. coli (O78:K80, O2:K1) | Single phage (TM3) Phage cocktail (TM1, TM2, TM3, TM4, TM5) | 1010 PFU in 200 μL via intramuscular injection | On days 7, 14, and 21 post-challenge, birds treated with the phage cocktail had a greater BW (p < 0.05) compared to infected control Moreover, the birds challenged with E. coli and treated with either a single phage or phage cocktail showed a significant decrease in mortality (26.3% and 13.3%, respectively) compared to the untreated infected control (46.6%) | [113] |

| E. coli (APEC O78) | APEC O78-specific bacteriophage | 108 PFU (Intratracheal inoculation) | Bacteriophage treatment reduced the mortality associated with infection of E. coli | [87] |

| Avian pathogenic E. coli | Naked phage (ΦKAZ14); Chitosan nanoparticles loaded phage (C-ΦKAZ14 NPs) | Dose 0.2 mL orally Concentration 107 PFU/mL | Chitosan nanoparticles loaded bacteriophage (ΦKAZ14) treatment significantly improved BW and decreased mortality % compared to the infected untreated group | [91] |

| Salmonella spp; C. perfringens | Commercial BP Product (From CTCBIO Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) containing a mixture of individual BP targeting Salmonella spp. and Clostridium perfringens | Dose 0.5 g/kg via diet Concentration 108 PFU per g 106 PFU per g | BP addition to the diet resulted in better FCR (p < 0.05) relative to the negative control treatment, fed only the basal diet | [94] |

| E. coli | SPR02 | Dose 200 mL sprayed on the surface area of 3.9 m2 pens Concentration 108 PFU/ml | Bacteriophage treatment of the litter significantly reduced mortality in the challenged birds | [114] |

| E. coli | Bacteriophage SPR02 | 1 ml of 3.9 × 109 pfu (via spray); and 0.1 ml of 3.9 × 108 pfu per bird (Intratracheal) | Intratracheal administration of BP SPR02 in challenged birds significantly decreased mortality % compared to the untreated challenged treatment | [115] |

| Salmonella enteritidis | Anti-SE bacteriophage | 0.05, 0.1 and 0.2% via feed Concentration 109 PFU/g | Anti-SE bacteriophage supplementation at 0.2% significantly decreased mortality % and increased relative leg muscle weight compared to the infected unsupplemented group | [98] |

| Salmonella spp.; E. coli | Bacteriophages used (S. gallinarum BP, S. typhimurium BP and S. enteritidis BP) | Doses 0.020% 0.035% 0.050% via feed Concentration 108 PFU per gram | Bacteriophage supplementation at all three doses resulted in a significant increase in egg production in comparison to the control group that fed only a basal diet during weeks 4 to 6. Moreover, BP at inclusion levels of 0.020% and 0.050% showed greater (p < 0.05) Haugh unit (HU) relative to the control group fed only a basal diet during weeks 5 and 6 | [100] |

| Salmonella gallinarum | Bacteriophage CJø01 | 106 PFU/kg via feed | Bacteriophage supplementation significantly decreased mortality in contact birds compared to unsupplemented contact birds | [102] |

| E. coli | Experiment-1 phi F78E Experiment-2 Phage cocktail (phi F78E, phi F258E and phi F61E) | phi F78E Doses 1 mL orally 1 mL spray Concentration 1.5 × 109 PFU/mL Phage cocktail 5.0 × 107 PFU/mL via spray and orally | Bacteriophage administered at 1.5 × 109 PFU/mL significantly decreased mortality and morbidity compared to the untreated infected group. In the second experiment, a phage cocktail administered at an inclusion level of 5.0 × 107 PFU/mL reduced flock mortality (to <0.5%) in E. coli-infected flock | [116] |

| E. coli | Bacteriophage EC1 | 0.2 mL of bacteriophage EC1 (1011 PFU/mL) via intratracheal | Infected birds treated with bacteriophage EC1 had higher body weight (15.4%) and lower mortality rates compared to untreated birds (13.3% vs. 83.3%) | [117] |

| Clostridium perfringens | Phage cocktail (INT-401) | 0.5 mL (2.5 × 109 PFU/bird via oral gavage | Birds challenged with CP and treated with INT-401 significantly (p < 0.05) reduced mortality (by 92%) and improved BWG and FCR compared to untreated infected controls | [118] |

| E. coli | Two bacteriophages (SPR02 and DAF6 used separately) | Dose 0.1 mL via IM injection Concentrations 4 × 109, 107, 105, or 103 PFU/ml | Broilers infected with E. coli and treated with BP SPR02 at a phage titer of 108 exhibited significantly decreased mortality compared to the infected group (7% vs. 48%) | [119] |

| Salmonella typhimurium (ST) | Phage cocktail (S2a, S9, and S11) | 5.4 × 106 PFU/0.5 mL/bird via orally | Broilers challenged with ST and treated with phage cocktail resulted in a significantly higher BWG compared to the infected control | [109] |

| E. coli | Phage cocktail (DAF6 and SPR02) | 3.7 × 109 and 9.3 × 109 PFU/mL, DAF6 and SPR02, respectively, via injection in the thigh | Birds challenged with E. coli and treated with BP cocktail significantly decreased mortality % compared to the infected control (15% vs. 68%) | [120] |

| E. coli | SPR02 | Study 1 103, 104, 106, and 108 PFU via air sac inoculation Study 2 103, 104, 106 PFU bacteriophage via drinking water | Study1 Birds infected with E. coli, and treated with 103, 104, and 106 PFU BP SPR02, significantly reduced mortality rates as compared to the infected control Study 2 Birds challenged with E. coli and supplemented with phage SPR02 at the inclusion of 103 PFU in drinking water resulted in a significantly higher BW compared to the infected control | [121] |

| E. coli | DAF6 and SPRO2 | 3.6 × 107 and 4.6 × 107 PFU/mL, of DAF6 and SPRO2, respectively (Aerosol spray) | Significantly improved BW and decreased mortality rate (50% less) compared to the PBS-treated challenged group on day 7 | [121] |

| Salmonella spp. | 3 phages 3ent1, 8sent65 and 8sent1748 | Dose 1 L of BAFASAL® for 75,000 birds Concentration 108 PFU/mL via drinking water | Bafasel® application reduced mortality and Salmonella-positive birds (by 94.2%), as well as improved FCR compared to the non-treated controls | [122] |

| Salmonella spp. | SalmoFree® Sciphage | 108 PFU/mL via drinking water | SalmoFree® eliminated the occurrence of Salmonella and had no impact on production metrics such as FI, BWG, and FCR | [86] |

| Salmonella spp. | Biotector S1® | Broilers 5 × 107, 1 × 108 and 2 × 108 PFU/kg via feed Broilers breeders 1 × 106 PFU/kg via feed Layers 1 × 108 PFU/kg via feed | Phage application decreased mortality by 73% and 53% in challenged broilers and broiler breeders, respectively, compared to the infected control In layers, phage application at 1 × 108 PFU/kg improved egg production by 3% (90.6% vs. 87.5% in control) and egg mass by 2.4% (59.2% vs. 56.8% in control) | [123] |

4.2.3. Impact of Bacteriophages on Blood Constituents and Immune Response

| Targeted Bacteria | Animal/Model | Phage | Dose and Route | Main Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli, Clostridium perfringens | Male Broilers (Cobb 500) | E. coli phage cocktail | 1 g/kg, and 2 g/kg feed | Supplementation of 1 g/kg phage cocktail alone significantly decreased the cholesterol levels compared to the control group (0 g/kg) and the higher dosage of phage cocktail (2 g/kg) | [66] |

| Salmonella | Male Broiler chickens (Ross-308) | Salmonella-specific phage cocktail (SPC) SP 75 SP 100 SP 175 | 0.075 g/kg, 0.1 g/kg, and 0.175 g/kg via feed | Supplementation of SPC resulted in a linear increase in monocytes, albumin, and globulin | [111] |

| Salmonella enteritidis | As hatched broiler chickens (Ross-308) | Commercial BP (ProBe-Bac®) | 1 g/kg 1.5 g/kg via diet | Supplementation of BP significantly decreased serum concentration of AST and increased concentrations of albumin, A/G ratio, and triglycerides | [68] |

| Clostridium perfringens | 1-day-old broiler chickens (Ross-308 unsexed) | Powdered and encapsulated BP | 106 PFU/g of diet | Chickens that were fed a diet supplemented with encapsulated BP showed the most elevated (p < 0.05) serum IgA levels | [72] |

| E. coli, Salmonella | Broilers (day-old chickens) | Bacteriophage cocktail (S. gallinarum, S. typhimurium, S. enteritidis) | Dose 0.25 g BP/Kg, 0.5 g BP/Kg Concentration 108 PFU/g | Bacteriophage supplementation did not significantly affect the blood profile (RBCs, PCV, Hb, WBCs, and lymphocytes) of experimental broiler chickens | [80] |

| Salmonella enteritidis | Single comb white leghorns (40 wk. old) | Commercial bacteriophage product containing 2 bacteriophages SP-1 and STP-1 | 0.1% BP and 0.2% BP via diet | Supplementation of BP at 0.1% and 0.2% significantly reduced IL-6 mRNA expression as compared to the infected control | [90] |

| Salmonella enteritidis | Male broilers (Ross 308) | Anti-SE bacteriophage | 0.05%, 0.1% and 0.2% via feed Concentration 109 PFU/g | Anti-SE bacteriophage supplementation decreased AST levels in blood and decreased LDL concentration in serum compared to the control group fed only a basal diet | [98] |

4.2.4. Application of Phages in Postharvest Products (Biocontrol Agents)

| Targeted Bacteria | Animal/Model | Phage Product | Dose & Route | Main Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. enteritidis | Chicken and turkey meat cuts | Commercial product (PhageGuard S, formerly called Salmonelex) | 1 and 2 × 107 PFU/cm2 The phage was applied by emersion to a final conc. of ∼7 log10 PFU/cm2 | Inoculating chicken and turkey meat with 4 log10 CFU/cm2 of S. enteritidis, followed by PhageGuard S treatment at both doses, resulted in a reduction of more than 1 log10 CFU/cm2 in S. enteritidis after 24 h | [125] |

| Salmonella spp. from ground chickens and other sources | Postharvest Salmonella-free boneless, skinless chicken meat | Commercial phage (Salmonelex™) | (~107 PFU/cm2) via tap and filtered water | When phage (diluted in sterile tap water) was applied to boneless chicken thighs and legs experimentally contaminated with Salmonella serovars, there was a more significant (p < 0.05) decrease in Salmonella, with a 0.39 log CFU/cm2 decrease observed, as opposed to a 0.23 log10 CFU/cm2 decrease with sterile filtered water | [126] |

| Salmonella spp. | Chicken breast | Commercial phage (SalmoFresh) | 108 and 109 PFU/mL via spray (surface application) for the samples up to 7 days of storage at 4 °C | Applying phage at 9 log PFU/mL decreased Salmonella by 1.0–1.1 log10 CFU/g, whereas 8 log PFU/mL achieved a reduction of 0.5–0.6 log10 CFU/g | [127] |

| Salmonella typhimurium | Chicken breast and chicken mince | P22 phage | 8 mL of P22 phage, having a concentration 1012 PFU/ml | In sliced breast and minced chicken, the P22 phage significantly decreased the Salmonella population by 1.0–2.0 log cycles | [128] |

| S. typhimurium and S. enteritidis | Chicken breasts | Bacteriophage Cocktail (UAB_Phi 20, UAB_Phi78, UAB_Phi87) | 100 mL phage cocktail having a concentration 109 PFU/mL | After dipping chicken breasts in a phage cocktail solution for five minutes and refrigerating at 4 °C for seven days, a significant decrease of 2.2 log10 CFU/g for S. typhimurium and 0.9 log10 CFU/g for S. enteritidis was recorded | [129] |

| S. enteritidis and S. typhimurium | Meat (chicken skin) | wksl3 phage | 2.2 × 108 PFU/mL via spray | Salmonella levels decreased by almost 2.5 logs after phage wksl3 was applied to chicken skin at 8 °C | [130] |

| S. enteritidis | Meat (chicken skin) | Phage cocktail | 100 mL used, having a concentration 109 PFU/mL via dipping | Bacteriophage cocktail application to chicken skin experimentally contaminated with S. enteritidis significantly decreased S. enteritidis by 1.0 log10 CFU/cm2 compared to the untreated infected control | [131] |

| Campylobacter jejuni NCTC 11168 and Campylobacter coli NCTC 12668 | Meat (Raw chicken) | Phage CP81, and Phage NCTC12684 | 1 mL phage lysate applied to the meat stored at 4 °C for up to 1 week | No reduction in Campylobacter number was detected in chicken meat following phage treatment | [132] |

| S. enteritidis | Broiler Meat | PHL 4 (Salmonella enteritidis phage type 13A) | 5.5 mL of 108 or 1010 PFU/mL via spray | The broiler carcasses treated with 5.5 × 108 or 1010 PFU of PHL 4 phage resulted in a 93% decrease in S. enteritidis levels as compared to the control group sprayed with sterile saline | [133] |

| Campylobacter jejuni | Meat (chicken skin) | C. jejuni phage 12673 | Dose 106 PFU/cm2 Applied to chicken skin Concentration log10 9.2 and 10.1 PFU/ml | Treatment with phage at 106 PFU/cm2 significantly lowered the Campylobacter numbers by almost 95%, compared to the untreated group | [134] |

| S. enteritidis | Meat (chicken skin) | Bacteriophage P22, 29C | P22 phage 7.1 × 102 PFU/mL 29C phage 8.1 × 102 PFU/mL via spray | BP P22 and 29C were administered to chicken skin (experimentally infected with S. enteritidis), significantly (p < 0.01) decreasing S. enteritidis by 98.7 and 99.2%, respectively, as compared to the untreated infected control | [134] |

| Campylobacter jejuni | Meat (chicken skin) | Bacteriophage Φ2 | 107 PFU | Phage application significantly (p < 0.0001) reduced Campylobacter recovery by 1log10 CFU/cm2 as compared to untreated inoculated control | [135] |

5. Role of Bacteriophages as Disinfectants in Poultry Operations

6. Emerging Trends in Phage Applications

7. Pros and Cons of Bacteriophages

8. Challenges of Using Phages in Poultry and Potential Solutions

8.1. Development and Risk of Phage Resistance

8.2. Phage Selection and Effective Delivery

8.3. Phage Behavior in Complex Microbiomes and In Vivo Systems

8.4. Environmental Release, Biosafety, and Phage Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) Challenges

8.5. Regulatory Concerns and Limitations

9. Future Prospects of Bacteriophage Therapy

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nhung, N.T.; Chansiripornchai, N.; Carrique-Mas, J.J. Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacterial Poultry Pathogens: A Review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lincke, S.J.; Wolf, J.J. Dietary Modeling of Greenhouse Gases Using Oecd Meat Consumption/Retail Availability Estimates. Int. J. Food Eng. 2023, 19, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.K.; Songer, J.G. Necrotic Enteritis in Chickens: A Paradigm of Enteric Infection by Clostridium perfringens Type A. Anaerobe 2009, 15, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yegani, M.; Korver, D.R. Factors Affecting Intestinal Health in Poultry. Poult. Sci. 2008, 87, 2052–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timbermont, L.; Haesebrouck, F.; Ducatelle, R.; Van Immerseel, F. Necrotic Enteritis in Broilers: An Updated Review on the Pathogenesis. Avian Pathol. 2011, 40, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, D.L. Multicausal Enteric Diseases. In Diseases of Poultry; Iowa State University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 2003; pp. 1169–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Hafez, H.M. Enteric Diseases of Poultry with Special Attention to Clostridium perfringens. Pak. Vet. J. 2011, 3, 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, D.P.; Knox, J.; Dehaeck, B.; Huntington, B.; Rathinam, T.; Ravipati, V.; Ayoade, S.; Gilbert, W.; Adebambo, A.O.; Jatau, I.D.; et al. Re-Calculating the Cost of Coccidiosis in Chickens. Vet. Res. 2020, 51, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, B.; Keyburn, A.; Seemann, T.; Rood, J.; Moore, R. Binding of Clostridium perfringens to Collagen Correlates with the Ability to Cause Necrotic Enteritis in Chickens. Vet. Microbiol. 2015, 180, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guabiraba, R.; Schouler, C. Avian Colibacillosis: Still Many Black Holes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2015, 362, fnv118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, S.M.L. Avian Colibacillosis and Salmonellosis: A Closer Look at Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Control and Public Health Concerns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Hack, M.E.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Shafi, M.E.; Alshahrani, O.A.; Saghir, S.A.; Al-Wajeeh, A.S.; Al-Shargi, O.Y.; Taha, A.E.; Mesalam, N.M.; Abdel-Moneim, A.M.E. Prebiotics Can Restrict Salmonella Populations in Poultry: A Review. Anim. Biotechnol. 2022, 33, 1668–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silveira, V.A.I.; Nishio, E.K.; Freitas, C.A.; Amador, I.R.; Kobayashi, R.K.; Caretta, T.; Macedo, F.; Celligoi, M.A.P. Production and Antimicrobial Activity of Sophorolipid against Clostridium perfringens and Campylobacter jejuni and Their Additive Interaction with Lactic Acid. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 101287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M.T.; Lubbers, B.V.; Schwarz, S.; Watts, J.L. Applying Definitions for Multidrug Resistance, Extensive Drug Resistance and Pandrug Resistance to Clinically Significant Livestock and Companion Animal Bacterial Pathogens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1460–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Immerseel, F.; De Buck, J.; Pasmans, F.; Huyghebaert, G.; Haesebrouck, F.; Ducatelle, R. Clostridium perfringens in Poultry: An Emerging Threat for Animal and Public Health. Avian Pathol. 2004, 33, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, H.M.; Huque, K.S.; Kamaruddin, K.M.; Beg, A.H. Global Restriction of Using Antibiotic Growth Promoters and Alternative Strategies in Poultry Production. Sci. Prog. 2018, 101, 52–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricke, S.C.; Rothrock, M.J., Jr. Gastrointestinal Microbiomes of Broilers and Layer Hens in Alternative Production Systems. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofacre, C.L.; Beacorn, T.; Collett, S.; Mathis, G. Using Competitive Exclusion, Mannan-Oligosaccharide and Other Intestinal Products to Control Necrotic Enteritis. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2003, 12, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Immerseel, F.; Rood, J.I.; Moore, R.J.; Titball, R.W. Rethinking Our Understanding of the Pathogenesis of Necrotic Enteritis in Chickens. Trends. Microbiol. 2009, 17, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelzer, K.; Wong, N.; Thomas, J.; Talkington, K.; Jungman, E.; Coukell, A. Antimicrobial Drug Use in Food-Producing Animals and Associated Human Health Risks: What, and How Strong, is the Evidence? BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenco, J.M.; Nunn, S.C.; Lee, E.J.; Dove, C.R.; Callaway, T.R.; Azain, M.J. Effect of Supplemental Protease on Growth Performance and Excreta Microbiome of Broiler Chicks. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zbikowska, K.; Michalczuk, M.; Dolka, B. The Use of Bacteriophages in the Poultry Industry. Animals 2020, 10, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Rothrock, M.J., Jr.; Ricke, S.C. Applications of Microbiome Analyses in Alternative Poultry Broiler Production Systems. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, G.; Das, R.K.; Brar, S.K.; Rouissi, T.; Ramirez, A.A.; Chorfi, Y.; Godbout, S. Alternatives to Antibiotics in Poultry Feed: Molecular Perspectives. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 44, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, H.-W. Bacteriophage Observations and Evolution. Microbiol. Res. 2003, 154, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.S.; Jeong, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Min, W.; Myung, H. Therapeutic Effects of Bacteriophages against Salmonella gallinarum Infection in Chickens. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 23, 1478–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, P.J.; Connerton, P.L.; Connerton, I.F. Phage Biocontrol of Campylobacter Jejuni in Chickens Does Not Produce Collateral Effects on the Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Belleghem, J.D.; Dąbrowska, K.; Vaneechoutte, M.; Barr, J.J.; Bollyky, P.L. Interactions between Bacteriophage, Bacteria, and the Mammalian Immune System. Viruses 2018, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortier, L.C.; Sekulovic, O. Importance of Prophages to Evolution and Virulence of Bacterial Pathogens. Virulence 2013, 4, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, E.; Campbell, K.; Grant, I.; McAuliffe, O. Understanding and Exploiting Phage-Host Interactions. Viruses 2019, 11, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, A.S. Phage Therapy-Constraints and Possibilities. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2014, 119, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twort, F.W. An Investigation on the Nature of Ultra-Microscopic Viruses. Lancet 1961, 2, 1241–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Herelle, M.F. Sur Un Microbe Invisible Antagoniste Des Bacilles Dysentériques. Acta Sci. 1961, 165, 373–375. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth, D.H. Who Discovered Bacteriophage? Bacteriol. Rev. 1976, 40, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Gomez, C.; Blanco-Picazo, P.; Brown-Jaque, M.; Quiros, P.; Rodriguez-Rubio, L.; Cerda-Cuellar, M.; Muniesa, M. Infectious Phage Particles Packaging Antibiotic Resistance Genes Found in Meat Products and Chicken Feces. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrique, P.; Bolduc, B.; Walk, S.T.; van der Oost, J.; de Vos, W.M.; Young, M.J. Healthy Human Gut Phageome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10400–10405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, A.B.; Kobiler, O.; Stavans, J.; Court, D.L.; Adhya, S. Switches in Bacteriophage Lambda Development. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2005, 39, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A. The Future of Bacteriophage Biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003, 4, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huff, G.R.; Huff, W.E.; Rath, N.C.; Donoghue, A.M. Critical Evaluation of Bacteriophage to Prevent and Treat Colibacillosis in Poultry. J. Ark. Acad. Sci. 2009, 63, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslik, M.; Baginska, N.; Jonczyk-Matysiak, E.; Wegrzyn, A.; Wegrzyn, G.; Gorski, A. Temperate Bacteriophages-the Powerful Indirect Modulators of Eukaryotic Cells and Immune Functions. Viruses 2021, 13, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard-Varona, C.; Hargreaves, K.R.; Abedon, S.T.; Sullivan, M.B. Lysogeny in Nature: Mechanisms, Impact and Ecology of Temperate Phages. ISME J. 2017, 11, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dec, M.; Wernicki, A.; Urban-Chmiel, R. Efficacy of Experimental Phage Therapies in Livestock. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2020, 21, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peh, E.; Szott, V.; Reichelt, B.; Friese, A.; Rösler, U.; Plötz, M.; Kittler, S. Bacteriophage Cocktail Application for Campylobacter Mitigation-from in Vitro to in Vivo. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melaku, M.; Wang, J.; Xie, Y.; Ali, A.; Yi, B.; Ma, T.; Zhong, R.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H. Reviving Hope: Phage Therapy Application for Antimicrobial Resistance in Farm Animal Production over the Past Decade. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2025, 324, 116333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneeb, M.; Khan, E.U.; Ahmad, S.; Naveed, S.; Ali, M.; Qazi, M.A.; Ahmad, T.; Abdollahi, M.R. An Updated Review on Alternative Strategies to Antibiotics against Necrotic Enteritis in Commercial Broiler Chickens. World Poult. Sci. 2024, 80, 821–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneeb, M.; Khan, E.U.; Saima; Suleman, M.; Awais, M.M.; Ahmad, S. Effects of Bacteriophage Supplementation on Performance, Gut Health and Blood Biochemistry in Broilers Challenged with Necrotic Enteritis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2025, 193, 105809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosimann, S.; Desiree, K.; Ebner, P. Efficacy of Phage Therapy in Poultry: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.; Sereno, R.; Nicolau, A.; Azeredo, J. The Influence of the Mode of Administration in the Dissemination of Three Coliphages in Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2009, 88, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jończyk-Matysiak, E.; Łodej, N.; Kula, D.; Owczarek, B.; Orwat, F.; Międzybrodzki, R.; Neuberg, J.; Bagińska, N.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B.; Górski, A. Factors Determining Phage Stability/Activity: Challenges in Practical Phage Application. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2019, 17, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, D.J.; Sokolov, I.J.; Vinner, G.K.; Mancuso, F.; Cinquerrui, S.; Vladisavljevic, G.T.; Clokie, M.R.; Garton, N.J.; Stapley, A.G.; Kirpichnikova, A. Formulation, Stabilisation and Encapsulation of Bacteriophage for Phage Therapy. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 249, 100–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.-H.; Islam, G.S.; Wu, Y.; Sabour, P.M.; Chambers, J.R.; Wang, Q.; Wu, S.X.Y.; Griffiths, M.W. Temporal Distribution of Encapsulated Bacteriophages during Passage through the Chick Gastrointestinal Tract. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 2911–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsattar, A.S.; Abdelrahman, F.; Dawoud, A.; Connerton, I.F.; El-Shibiny, A. Encapsulation of E. Coli Phage Zcec5 in Chitosan–Alginate Beads as a Delivery System in Phage Therapy. AMB Express 2019, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Authority European Food Safety. The European Union One Health 2018 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2019, 17, e05926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, A.B.; Rees, C.D.; Barrow, P.; Hagens, S.; Harper, D.R. Bacteriophage Applications: Where Are We Now? Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 51, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moye, Z.D.; Woolston, J.; Sulakvelidze, A. Bacteriophage Applications for Food Production and Processing. Viruses 2018, 10, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, L.K.; Barnes, H.J.; Vaillancourt, J.P.; Abdul-Aziz, T.A.; Logue, C.M. Colibacillosis; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 751–805. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, O.; Kassem, I.I.; Shen, Z.; Lin, J.; Rajashekara, G.; Zhang, Q. Campylobacter in Poultry: Ecology and Potential Interventions. Avian Dis. 2015, 59, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäckel, C.; Hammerl, J.A.; Hertwig, S. Campylobacter Phage Isolation and Characterization: What We Have Learned So Far. Methods Protoc. 2019, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.W. The Bacteriophages of Clostridium perfringens. Microbiol. 1959, 21, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seal, B.S. Characterization of Bacteriophages Virulent for Clostridium perfringens and Identification of Phage Lytic Enzymes as Alternatives to Antibiotics for Potential Control of the Bacterium. Poult. Sci. 2013, 92, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M.; Vukov, N.; Scherer, S.; Loessner, M.J. The Murein Hydrolase of the Bacteriophage Φ3626 Dual Lysis System Is Active against All Tested Clostridium perfringens Strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 5311–5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervasi, T.; Horn, N.; Wegmann, U.; Dugo, G.; Narbad, A.; Mayer, M.J. Expression and Delivery of an Endolysin to Combat Clostridium perfringens. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 2495–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loponte, R.; Pagnini, U.; Iovane, G.; Pisanelli, G. Phage Therapy in Veterinary Medicine. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogun, K.; Peh, E.; Meyer-Kühling, B.; Hartmann, J.; Hirnet, J.; Plötz, M.; Kittler, S. Investigating Bacteriophages as a Novel Multiple-Hurdle Measure against Campylobacter: Field Trials in Commercial Broiler Plants. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourabadeh, A.H.; Madani, S.A.; Dorostkar, R.; Rezaeian, M.; Esmaeili, H.; Bolandian, M.; Salavati, A.; Hashemian, S.M.M.; Aghahasani, A. Evaluation of the in Vitro and in Vivo Efficiency of in-Feed Bacteriophage Cocktail Application to Control Salmonella typhimurium and Salmonella enteritidis Infection in Broiler Chicks. Avian. Pathol. 2024, 53, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaufi, M.A.M.; Sieo, C.C.; Chong, C.W.; Tan, G.H.; Omar, A.R.; Ho, Y.W. Multiple Factorial Analysis of Growth Performance, Gut Population, Lipid Profiles, Immune Responses, Intestinal Histomorphology, and Relative Organ Weights of Cobb 500 Broilers Fed a Diet Supplemented with Phage Cocktail and Probiotics. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 23, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, N.T.A.; Lan, L.T.T.; Linh, N.T.; Dang, C.C.; Phuc, N.H.; Tuan, T.D.; Ngu, N.T. Effects of Bacteriophage Cocktail to Prevent Salmonella enteritidis in Native Broiler Chickens. J. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2023, 11, 1218–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrami, Z.; Sedghi, M.; Mohammadi, I.; Bedford, M.; Miranzadeh, H.; Ghasemi, R. Effects of Bacteriophage on Salmonella enteritidis Infection in Broilers. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuźmińska-Bajor, M.; Śliwka, P.; Korzeniowski, P.; Kuczkowski, M.; Moreno, D.S.; Woźniak-Biel, A.; Śliwińska, E.; Grzymajło, K. Effective Reduction of Salmonella enteritidis in Broiler Chickens Using the Upwr_S134 Phage Cocktail. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1136261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanki, A.M.; Hooton, S.; Whenham, N.; Salter, M.G.; Bedford, M.R.; O’NEill, H.V.M.; Clokie, M.R.J. A Bacteriophage Cocktail Delivered in Feed Significantly Reduced Salmonella Colonization in Challenged Broiler Chickens. Emerg. Microbes. Infect. 2023, 12, 2217947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, C.A.P.-D.; Gómez-Verduzco, G.; Márquez-Mota, C.C.; Téllez-Isaías, G.; Kwon, Y.M.; Cortés-Cuevas, A.; Arce-Menocal, J.; Martínez-Gómez, D.; Ávila-González, E. Productive Performance and Cecum Microbiota Analysis of Broiler Chickens Supplemented with Beta-Mannanases and Bacteriophages-a Pilot Study. Animals 2022, 12, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-G.; Kim, Y.-B.; Lee, S.-H.; Moon, J.-O.; Chae, J.-P.; Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, K.-W. In Vivo Recovery of Bacteriophages and Their Effects on Clostridium perfringens-Infected Broiler Chickens. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, S.; Tolba, H.M.; Hamed, R.I.; Al-Atfeehy, N.M. Bacteriophage Therapy as an Alternative Biocontrol against Emerging Multidrug Resistant E. Coli in Broilers. Saudi. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 3380–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evran, S.; Tayyarcan, E.K.; Acar-Soykut, E.; Boyaci, I.H. Applications of Bacteriophage Cocktails to Reduce Salmonella Contamination in Poultry Farms. Food. Environ. Virol. 2022, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korzeniowski, P.; Śliwka, P.; Kuczkowski, M.; Mišić, D.; Milcarz, A.; Kuźmińska-Bajor, M. Bacteriophage Cocktail Can Effectively Control Salmonella Biofilm in Poultry Housing. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 901770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhaya, S.D.; Ahn, J.M.; Cho, J.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Kang, D.K.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, H.B.; Kim, I.H. Bacteriophage Cocktail Supplementation Improves Growth Performance, Gut Microbiome and Production Traits in Broiler Chickens. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’angelantonio, D.; Scattolini, S.; Boni, A.; Neri, D.; Di Serafino, G.; Connerton, P.; Connerton, I.; Pomilio, F.; Di Giannatale, E.; Migliorati, G.; et al. Bacteriophage Therapy to Reduce Colonization of Campylobacter Jejuni in Broiler Chickens before Slaughter. Viruses 2021, 13, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, D.; Lee, J.-W.; Chae, J.-P.; Kim, J.-W.; Eun, J.-S.; Lee, K.-W.; Seo, K.-H. Characterization of a Novel Bacteriophage Phicj22 and Its Prophylactic and Inhibitory Effects on Necrotic Enteritis and Clostridium perfringens in Broilers. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosny, R.A.; Gaber, A.F.; Sorour, H.K. Bacteriophage Mediated Control of Necrotic Enteritis Caused by C. Perfringens in Broiler Chickens. Vet. Res. Commun. 2021, 45, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, M.; Runa, N.; Husna, A.; Rahman, M.; Rajib, D.M.; Mahbub-e-Elahi, A.T.; Rahman, M.M. Evaluation of the Effect of Dietary Supplementation of Bacteriophage on Production Performance and Excreta Microflora of Commercial Broiler and Layer Chickens in Bangladesh. MOJ Proteom. Bioinform. 2020, 9, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kittler, S.; Mengden, R.; Korf, I.H.E.; Bierbrodt, A.; Wittmann, J.; Plotz, M.; Jung, A.; Lehnherr, T.; Rohde, C.; Lehnherr, H.; et al. Impact of Bacteriophage-Supplemented Drinking Water on the E. Coli Population in the Chicken Gut. Pathogens 2020, 9, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinivasagam, H.N.; Estella, W.; Maddock, L.; Mayer, D.G.; Weyand, C.; Connerton, P.L.; Connerton, I.F. Bacteriophages to Control Campylobacter in Commercially Farmed Broiler Chickens, in Australia. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimminau, E.A.; Russo, K.N.; Karnezos, T.P.; Oh, H.G.; Lee, J.J.; Tate, C.C.; Baxter, J.A.; Berghaus, R.D.; Hofacre, C.L. Bacteriophage in-Feed Application: A Novel Approach to Preventing Salmonella enteritidis Colonization in Chicks Fed Experimentally Contaminated Feed. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2020, 29, 930–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorour, H.K.; Gaber, A.F.; Hosny, R.A. Evaluation of the Efficiency of Using Salmonella kentucky and Escherichia coli O119 Bacteriophages in the Treatment and Prevention of Salmonellosis and Colibacillosis in Broiler Chickens. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 71, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Lin, H.; Jing, Y.; Wang, J. Broad-Host-Range Salmonella Bacteriophage Stp4-a and Its Potential Application Evaluation in Poultry Industry. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 3643–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavijo, V.; Baquero, D.; Hernandez, S.; Farfan, J.C.; Arias, J.; Arevalo, A.; Donado-Godoy, P.; Vives-Flores, M. Phage Cocktail Salmofree® Reduces Salmonella on a Commercial Broiler Farm. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 5054–5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawakol, M.M.; Nabil, N.M.; Samy, A. Evaluation of Bacteriophage Efficacy in Reducing the Impact of Single and Mixed Infections with Escherichia coli and Infectious Bronchitis in Chickens. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2019, 9, 1686822. [Google Scholar]

- Vaz, C.S.L.; Voss-Rech, D.; Alves, L.; Coldebella, A.; Brentano, L.; Trevisol, I.M. Effect of Time of Therapy with Wild-Type Lytic Bacteriophages on the Reduction of Salmonella enteritidis in Broiler Chickens. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 240, 108527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabil, N.M.; Tawakol, M.M.; Hassan, H.M. Assessing the Impact of Bacteriophages in the Treatment of Salmonella in Broiler Chickens. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2018, 8, 1539056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, P.A.; Cosby, D.E.; Cox, N.A.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, W.K. Effect of Dietary Bacteriophage Supplementation on Internal Organs, Fecal Excretion, and Ileal Immune Response in Laying Hens Challenged by Salmonella enteritidis. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 3264–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaikabo, A.A.; AbdulKarim, S.M.; Abas, F. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Chitosan Nanoparticles Loaded Phikaz14 Bacteriophage in the Biological Control of Colibacillosis in Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Torshizi, M.A.K.; Rahimi, S.; Dennehy, J.J. Prophylactic Bacteriophage Administration More Effective Than Post-Infection Administration in Reducing Salmonella enterica Serovar Enteritidis Shedding in Quail. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.W.; Shin, H.S.; Kim, M.C.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, G.B.; Kil, D.Y. Effect of Dietary Supplementation of Bacteriophage on Performance, Egg Quality and Caecal Bacterial Populations in Laying Hens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2015, 56, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, B.B.; Lee, G.I.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, G.B.; Kil, D.Y. Effect of Dietary Supplementation of Bacteriophage on Growth Performance and Cecal Bacterial Populations in Broiler Chickens Raised in Different Housing Systems. Livest. Sci. 2014, 170, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, G.A.; Donato, T.C.; Baptista, A.A.; Correa, I.M.; Garcia, K.C.; Filho, R.L.A. Bacteriophage-Induced Reduction in Salmonella enteritidis Counts in the Crop of Broiler Chickens Undergoing Preslaughter Feed Withdrawal. Poult. Sci. 2014, 93, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, S.; Kittler, S.; Klein, G.; Glunder, G. Impact of a Single Phage and a Phage Cocktail Application in Broilers on Reduction of Campylobacter jejuni and Development of Resistance. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.P.; Yan, L.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, I.H. Evaluation of Bacteriophage Supplementation on Growth Performance, Blood Characteristics, Relative Organ Weight, Breast Muscle Characteristics and Excreta Microbial Shedding in Broilers. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 26, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.H.; Lee, G.Y.; Jang, J.C.; Kim, J.E.; Kim, Y.Y. Evaluation of Anti-Se Bacteriophage as Feed Additives to Prevent Salmonella enteritidis, (Se) in Broiler. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 26, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.H.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, Y.N.; Park, J.K.; Youn, H.N.; Lee, H.J.; Yang, S.Y.; Cho, Y.W.; Lee, J.B.; et al. Use of Bacteriophage for Biological Control of Salmonella enteritidis Infection in Chicken. Res. Vet. Sci. 2012, 93, 1173–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.Y.; Baek, H.Y.; Kim, I.H. Effects of Bacteriophage Supplementation on Egg Performance, Egg Quality, Excreta Microflora, and Moisture Content in Laying Hens. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 25, 1015–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardina, C.; Spricigo, D.A.; Cortes, P.; Llagostera, M. Significance of the Bacteriophage Treatment Schedule in Reducing Salmonella Colonization of Poultry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 6600–6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.H.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, Y.N.; Park, J.K.; Youn, H.N.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, H.J.; Yang, S.Y.; Cho, Y.W.; Lee, J.B.; et al. Efficacy of Bacteriophage Therapy on Horizontal Transmission of Salmonella gallinarum on Commercial Layer Chickens. Avian. Dis. 2011, 55, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shibiny, A.; Scott, A.; Timms, A.; Metawea, Y.; Connerton, P.; Connerton, I. Application of a Group Ii Campylobacter Bacteriophage to Reduce Strains of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli Colonizing Broiler Chickens. J. Food. Prot. 2009, 72, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borie, C.; Albala, I.; Sanchez, P.; Sanchez, M.L.; Ramirez, S.; Navarro, C.; Morales, M.A.; Retamales, A.J.; Robeson, J. Bacteriophage Treatment Reduces Salmonella Colonization of Infected Chickens. Avian. Dis. 2008, 52, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atterbury, R.J.; Van Bergen, M.A.; Ortiz, F.; Lovell, M.A.; Harris, J.A.; De Boer, A.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Allen, V.M.; Barrow, P.A. Bacteriophage Therapy to Reduce Salmonella Colonization of Broiler Chickens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 4543–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreatti Filho, R.L.; Higgins, J.P.; Higgins, S.E.; Gaona, G.; Wolfenden, A.D.; Tellez, G.; Hargis, B.M. Ability of Bacteriophages Isolated from Different Sources to Reduce Salmonella enterica Serovar Enteritidis in Vitro and in Vivo. Poult. Sci. 2007, 86, 1904–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, C.L.; Atterbury, R.J.; El-Shibiny, A.; Connerton, P.L.; Dillon, E.; Scott, A.; Connerton, I.F. Bacteriophage Therapy to Reduce Campylobacter jejuni Colonization of Broiler Chickens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 6554–6563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagenaar, J.A.; Van Bergen, M.A.; Mueller, M.A.; Wassenaar, T.M.; Carlton, R.M. Phage Therapy Reduces Campylobacter jejuni Colonization in Broilers. Vet. Microbiol. 2005, 109, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, H.; Price, S.B.; McKee, A.S.; Hoerr, F.J.; Krehling, J.; Perdue, M.; Bauermeister, L. Use of Bacteriophages in Combination with Competitive Exclusion to Reduce Salmonella from Infected Chickens. Avian Dis. 2005, 49, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla-Navarro, S.; Torres-Boncompte, J.; Garcia-Llorens, J.; Bernabeu-Gimeno, M.; Domingo-Calap, P.; Catala-Gregori, P. Fighting Salmonella infantis: Bacteriophage-Driven Cleaning and Disinfection Strategies for Broiler Farms. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1401479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dlamini, S.B.; Mnisi, C.M.; Ateba, C.N.; Egbu, C.F.; Mlambo, V. In-Feed Salmonella-Specific Phages Alter the Physiology, Intestinal Histomorphology, and Carcass and Meat Quality Parameters in Broiler Chickens. Sci. Afri. 2023, 21, e01756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Tang, N.; Wang, X.; Ren, H.; Zhang, C.; Zou, L.; Han, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, W. Characterization of a Lytic Escherichia coli Phage Ce1 and Its Potential Use in Therapy against Avian Pathogenic Escherichia coli Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1091442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghizadeh, M.; Torshizi, M.A.K.; Rahimi, S.; Dalgaard, T.S. Synergistic Effect of Phage Therapy Using a Cocktail Rather Than a Single Phage in the Control of Severe Colibacillosis in Quails. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Gohary, F.A.; Huff, W.E.; Huff, G.R.; Rath, N.C.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Donoghue, A.M. Environmental Augmentation with Bacteriophage Prevents Colibacillosis in Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2014, 93, 2788–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huff, W.E.; Huff, G.R.; Rath, N.C.; Donoghue, A.M. Method of Administration Affects the Ability of Bacteriophage to Prevent Colibacillosis in 1-Day-Old Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2013, 92, 930–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.; Sereno, R.; Azeredo, J. In Vivo Efficiency Evaluation of a Phage Cocktail in Controlling Severe Colibacillosis in Confined Conditions and Experimental Poultry Houses. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 146, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, G.L.; Sieo, C.C.; Tan, W.S.; Hair-Bejo, M.; Jalila, A.; Ho, Y.W. Efficacy of a Bacteriophage Isolated from Chickens as a Therapeutic Agent for Colibacillosis in Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2010, 89, 2589–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.W.; Skinner, E.J.; Sulakvelidze, A.; Mathis, G.F.; Hofacre, C.L. Bacteriophage Therapy for Control of Necrotic Enteritis of Broiler Chickens Experimentally Infected with Clostridium perfringens. Avian. Dis. 2010, 54, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, W.E.; Huff, G.R.; Rath, N.C.; Donoghue, A.M. Evaluation of the Influence of Bacteriophage Titer on the Treatment of Colibacillosis in Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2006, 85, 1373–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, W.E.; Huff, G.R.; Rath, N.C.; Balog, J.M.; Donoghue, A.M. Therapeutic Efficacy of Bacteriophage and Baytril, (Enrofloxacin) Individually and in Combination to Treat Colibacillosis in Broilers. Poult. Sci. 2004, 83, 1944–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, W.E.; Huff, G.R.; Rath, N.C.; Balog, J.M.; Xie, H.; Moore, P.A., Jr.; Donoghue, A.M. Prevention of Escherichia Coli Respiratory Infection in Broiler Chickens with Bacteriophage, (Spr02). Poult. Sci. 2002, 81, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, E.A.; Wojtasik, A.; Górecka, E.; Stanczyk, M.; Dastych, J. Application of Bacteriophage Preparation Bafasal® in Broiler Chickens Experimentally Exposed to Salmonella spp. Viruses 2015, 2, 241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, J.; Trautner, C.; Witte, A.K.; Fister, S.; Schoder, D.; Rossmanith, P.; Mester, P.J. Don’t Shut the Stable Door after the Phage Has Bolted-the Importance of Bacteriophage Inactivation in Food Environments. Viruses 2019, 11, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sillankorva, S.M.; Oliveira, H.; Azeredo, J. Bacteriophages and Their Role in Food Safety. Int. J. Microbiol. 2012, 2012, 863945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagens, S.; De Vegt, B.; Peterson, R. Efficacy of a Commercial Phage Cocktail in Reducing Salmonella Contamination on Poultry Products-Laboratory Data and Industrial Trial Data. Int. J. Microbiol. 2018, 2, 863945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.; Parveen, S.; Schwarz, J.; Hashem, F.; Vimini, B. Reduction of Salmonella in Ground Chicken Using a Bacteriophage. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 2845–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukumaran, A.T.; Nannapaneni, R.; Kiess, A.; Sharma, C.S. Reduction of Salmonella on Chicken Meat and Chicken Skin by Combined or Sequential Application of Lytic Bacteriophage with Chemical Antimicrobials. Int. J. Food. Microbiol. 2015, 207, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinno, P.; Devirgiliis, C.; Ercolini, D.; Ongeng, D.; Mauriello, G. Bacteriophage P22 to Challenge Salmonella in Foods. Int. J. Food. Microbiol. 2014, 191, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spricigo, D.A.; Bardina, C.; Cortés, P.; Llagostera, M. Use of a Bacteriophage Cocktail to Control Salmonella in Food and the Food Industry. Int. J. Food. Microbiol. 2013, 165, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.-W.; Kim, J.-W.; Jung, T.-S.; Woo, G.-J. Wksl3, a New Biocontrol Agent for Salmonella enterica Serovars Enteritidis and Typhimurium in Foods: Characterization, Application, Sequence Analysis, and Oral Acute Toxicity Study. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 1956–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungaro, H.M.; Mendonça, R.C.S.; Gouvêa, D.M.; Vanetti, M.C.D.; de Oliveira Pinto, C.L. Use of Bacteriophages to Reduce Salmonella in Chicken Skin in Comparison with Chemical Agents. Int. Food Res. 2013, 52, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orquera, S.; Golz, G.; Hertwig, S.; Hammerl, J.; Sparborth, D.; Joldic, A.; Alter, T. Control of Campylobacter spp. and Yersinia enterocolitica by Virulent Bacteriophages. J. Mol. Genet. Med. 2012, 6, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Higgins, S.E.; Guenther, K.L.; Huff, W.; Donoghue, A.M.; Donoghue, D.J.; Hargis, B.M. Use of a Specific Bacteriophage Treatment to Reduce Salmonella in Poultry Products. Poult. Sci. 2005, 84, 1141–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, D.; Allen, V.M.; Barrow, P.A. Reduction of Experimental Salmonella and Campylobacter Contamination of Chicken Skin by Application of Lytic Bacteriophages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 5032–5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atterbury, R.J.; Connerton, P.L.; Dodd, C.E.; Rees, C.E.; Connerton, I.F. Application of Host-Specific Bacteriophages to the Surface of Chicken Skin Leads to a Reduction in Recovery of Campylobacter jejuni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 6302–6306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Ornellas Dutka Garcia, K.C.; de Oliveira Correa, I.M.; Pereira, L.Q.; Silva, T.M.; de Souza Ribeiro Mioni, M.; de Moraes Izidoro, A.C.; Bastos, I.H.V.; Goncalves, G.A.M.; Okamoto, A.S.; Filho, R.L.A. Bacteriophage Use to Control Salmonella Biofilm on Surfaces Present in Chicken Slaughterhouses. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 3392–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denes, T.; den Bakker, H.C.; Tokman, J.I.; Guldimann, C.; Wiedmann, M. Selection and Characterization of Phage-Resistant Mutant Strains of Listeria monocytogenes Reveal Host Genes Linked to Phage Adsorption. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 4295–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinay, M.; Franche, N.; Gregori, G.; Fantino, J.R.; Pouillot, F.; Ansaldi, M. Phage-Based Fluorescent Biosensor Prototypes to Specifically Detect Enteric Bacteria Such as E. coli and Salmonella enterica Typhimurium. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meile, S.; Sarbach, A.; Du, J.; Schuppler, M.; Saez, C.; Loessner, M.J.; Kilcher, S. Engineered Reporter Phages for Rapid Bioluminescence-Based Detection and Differentiation of Viable Listeria Cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00442-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasyagin, E.A.; Zykova, A.A.; Mardanova, E.S.; Nikitin, N.A.; Shuklina, M.A.; Ozhereleva, O.O.; Stepanova, L.A.; Tsybalova, L.M.; Blokhina, E.A.; Ravin, N.V. Influenza A Vaccine Candidates Based on Virus-like Particles Formed by Coat Proteins of Single-Stranded RNA Phages Beihai32 and PQ465. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, P.; Mahalingam, M.; Zhu, J.; Moayeri, M.; Sha, J.; Lawrence, W.S.; Leppla, S.H.; Chopra, A.K.; Rao, V.B. A Bacteriophage T4 Nanoparticle-Based Dual Vaccine against Anthrax and Plague. mBio 2018, 9, e01926-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Pan, P.; Ye, J.J.; Zhang, Q.L.; Zhang, X.Z. Hybrid M13 Bacteriophage-Based Vaccine Platform for Personalized Cancer Immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2022, 289, 121763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, P.; Zhu, J.; Mahalingam, M.; Batra, H.; Rao, V.B. Bacteriophage T4 Nanoparticles for Vaccine Delivery against Infectious Diseases. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 2019, 145, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittebole, X.; De Roock, S.; Opal, S.M. A Historical Overview of Bacteriophage Therapy as an Alternative to Antibiotics for the Treatment of Bacterial Pathogens. Virulence 2014, 5, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azeredo, J.; Sutherland, I.W. The Use of Phages for the Removal of Infectious Biofilms. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2008, 9, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Du, F.; Long, M.; Li, P. Limitations of Phage Therapy and Corresponding Optimization Strategies: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, J.J.; Hyman, P. Phage Choice, Isolation, and Preparation for Phage Therapy. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2010, 11, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, B.K.; Abedon, S.T.; Loc-Carrillo, C. Phage Cocktails and the Future of Phage Therapy. Future. Microbiol. 2013, 8, 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carascal, M.B.; Cruz-Papa, D.M.D.; Remenyi, R.; Cruz, M.C.B.; Destura, R.V. Phage Revolution against Multidrug-Resistant Clinical Pathogens in Southeast Asia. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 820572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berchieri, A., Jr.; Lovell, M.A.; Barrow, P.A. The Activity in the Chicken Alimentary Tract of Bacteriophages Lytic for Salmonella typhimurium. Res. Microbiol. 1991, 142, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigot, B.; Lee, W.J.; McIntyre, L.; Wilson, T.; Hudson, J.A.; Billington, C.; Heinemann, J.A. Control of Listeria Monocytogenes Growth in a Ready-to-Eat Poultry Product Using a Bacteriophage. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 1448–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanki, A.M.; Hooton, S.; Gigante, A.M.; Atterbury, R.J.; Clokie, M.R. Potential Roles for Bacteriophages in Reducing Salmonella from Poultry and Swine. In Salmonella spp.—A Global Challenge; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Caflisch, K.M.; Suh, G.A.; Patel, R. Biological Challenges of Phage Therapy and Proposed Solutions: A Literature Review. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2019, 17, 1011–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, M.F.; Alsaedi, A.A.; Hayder, A.Q.; Bougafa, F.H.E.; Al-Bofkane, N.M. Invasive Bacteriophages between a Bell and a Hammer: A Comprehensive Review of Pharmacokinetics and Bacterial Defense Systems. Discover Life 2025, 55, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, R.A.; Sakr, M.M.; Shebl, R.I.; Aboshanab, K.M. Recent Insights on Challenges Encountered with Phage Therapy against Gastrointestinal-Associated Infections. Gut Pathog. 2025, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, T.; Salabarria, A.-C.; Roach, D.R. Phage Therapy in the Resistance Era: Where Do We Stand and Where Are We Going? Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, 1659–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranveer, S.A.; Dasriya, V.; Ahmad, F.; Dhillon, H.S.; Samtiya, M.; Shama, E.; Anand, T.; Dhewa, T.; Chaudhary, V.; Chaudhary, P.; et al. Positive and Negative Aspects of Bacteriophages and Their Immense Role in the Food Chain. npj Sci. Food 2024, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferriol-González, C.; Concha-Eloko, R.; Bernabéu-Gimeno, M.; Fernández-Cuenca, F.; Cañada-García, J.E.; García-Cobos, S.; Sanjuán, R.; Domingo-Calap, P. Targeted Phage Hunting to Specific Klebsiella Pneumoniae Clinical Isolates Is an Efficient Antibiotic Resistance and Infection Control Strategy. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e00254-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, K.C.; Kurt, H.; Tokuç, E.; Özbey, D.; Arabacı, D.N.; Aydın, S.; Gönüllü, N.; Skurnik, M.; Tokman, H.B. Isolation and Characterization of New Lytic Bacteriophage Psa-Kc1 against Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates from Cystic Fibrosis Patients. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Chen, I.A.; Qimron, U. Engineering Phages to Fight Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 933–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.A.; El Houjeiry, S.; Kanj, S.S.; Matar, G.M.; Saba, E.S. From Forgotten Cure to Modern Medicine: The Resurgence of Bacteriophage Therapy. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 39, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanki, A.M.; Osei, E.K.; Whenham, N.; Salter, M.G.; Bedford, M.R.; Masey O’Neill, H.V.; Clokie, M.R. Broad Host Range Phages Target Global Clostridium Perfringens Bacterial Strains and Clear Infection in Five-Strain Model Systems. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e03784-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulani, M.S.; Kamble, E.E.; Kumkar, S.N.; Tawre, M.S.; Pardesi, K.R. Emerging Strategies to Combat Eskape Pathogens in the Era of Antimicrobial Resistance: A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, S.; He, X.; Tong, Y. Editorial: Phage Biology and Phage Therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 891848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, M.E.K.; Hodges, F.E.; Nale, J.Y.; Mahony, J.; van Sinderen, D.; Kaczorowska, J.; Alrashid, B.; Akter, M.; Brown, N.; Sauvageau, D.; et al. Analysis of Selection Methods to Develop Novel Phage Therapy Cocktails against Antimicrobial Resistant Clinical Isolates of Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 613529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godsil, M.; Ritz, N.L.; Venkatesh, S.; Meeske, A.J. Gut Phages and Their Interactions with Bacterial and Mammalian Hosts. J. Bacteriol. 2025, 207, e0042824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, F.; Menor-Flores, M.; Fernández, L.; Vega-Rodríguez, M.A.; García, P. Systematic Analysis of Putative Phage-Phage Interactions on Minimum-Sized Phage Cocktails. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peez, C.; Chen, B.; Henssler, L.; Chittò, M.; Onsea, J.; Verhofstad, M.H.J.; Arens, D.; Constant, C.; Zeiter, S.; Obremskey, W.; et al. Evaluating the Safety, Pharmacokinetics and Efficacy of Phage Therapy in Treating Fracture-Related Infections with Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus: Intravenous versus Local Application in Sheep. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1547250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qadir, M.I.; Mobeen, T.; Masood, A. Phage Therapy: Progress in Pharmacokinetics. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 54, e17093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, L.; Bleriot, I.; Fernández-Grela, P.; Paño-Pardo, J.R.; Oteo-Iglesias, J.; Tomás, M. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics Studies of Phage Therapy. Farm. Hosp. 2025, 49, T407–T412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, B.; Munoz Pineiro, A.; Pirnay, J. Overview and Outlook of Phage Therapy and Phage Biocontrol; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, J.A.M.; Rocha, E.P.C. Environmental Structure Drives Resistance to Phages and Antibiotics during Phage Therapy and to Invading Lysogens during Colonisation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Bagchi, D.; Chen, I.A. Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution of Phages and Their Current Applications in Antimicrobial Therapy. Adv. Ther. 2024, 7, 2300355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosco, K.; Lynch, S.; Sandaradura, I.; Khatami, A. Therapeutic Phage Monitoring: A Review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, S384–S394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards. Evaluation of the Safety and Efficacy of Listex™ P100 for Reduction of Pathogens on Different Ready-to-Eat, (Rte) Food Products. EFSA J. 2016, 14, e04565. [Google Scholar]

- Naureen, Z.; Malacarne, D.; Anpilogov, K.; Dautaj, A.; Camilleri, G.; Cecchin, S.; Bressan, S.; Casadei, A.; Albion, E.; Sorrentino, E.; et al. Comparison between American and European Legislation in the Therapeutical and Alimentary Bacteriophage Usage. Acta. Biomed. 2020, 91, e2020023. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Lin, H.; Ji, X.; Yan, G.; Lei, L.; Han, W.; Gu, J.; Huang, J. Therapeutic Applications of Lytic Phages in Human Medicine. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 142, 104048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Van Belleghem, J.D.; de Vries, C.R.; Burgener, E.; Chen, Q.; Manasherob, R.; Aronson, J.R.; Amanatullah, D.F.; Tamma, P.D.; Suh, G.A. The Safety and Toxicity of Phage Therapy: A Review of Animal and Clinical Studies. Viruses 2021, 13, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolston, J.; Sulakvelidze, A. Bacteriophages and Food Safety; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Leverentz, B.; Conway, W.S.; Janisiewicz, W.; Camp, M.J. Optimizing Concentration and Timing of a Phage Spray Application to Reduce Listeria Monocytogenes on Honeydew Melon Tissue. J. Food Prot. 2004, 67, 1682–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.N.; Abuladze, T.; Li, M.; Woolston, J.; Sulakvelidze, A. Bacteriophage Cocktail Significantly Reduces or Eliminates Listeria Monocytogenes Contamination on Lettuce, Apples, Cheese, Smoked Salmon and Frozen Foods. Food Microbiol. 2015, 52, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soffer, N.; Woolston, J.; Li, M.; Das, C.; Sulakvelidze, A. Bacteriophage Preparation Lytic for Shigella Significantly Reduces Shigella sonnei Contamination in Various Foods. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuladze, T.; Li, M.; Menetrez, M.Y.; Dean, T.; Senecal, A.; Sulakvelidze, A. Bacteriophages Reduce Experimental Contamination of Hard Surfaces, Tomato, Spinach, Broccoli, and Ground Beef by Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 6230–6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Patel, J.R.; Conway, W.S.; Ferguson, S.; Sulakvelidze, A. Effectiveness of Bacteriophages in Reducing Escherichia coli O157:H7 on Fresh-Cut Cantaloupes and Lettuce. J. Food Prot. 2009, 72, 1481–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.D.; Parks, A.; Abuladze, T.; Li, M.; Woolston, J.; Magnone, J.; Senecal, A.; Kropinski, A.M.; Sulakvelidze, A. Bacteriophage Cocktail Significantly Reduces Escherichia coli O157. Bacteriophage 2012, 2, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyacioglu, O.; Sharma, M.; Sulakvelidze, A.; Goktepe, I. Biocontrol of Escherichia coli O157. Bacteriophage 2013, 3, e24620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnone, J.P.; Marek, P.J.; Sulakvelidze, A.; Senecal, A.G. Additive Approach for Inactivation of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Shigella spp. On Contaminated Fresh Fruits and Vegetables Using Bacteriophage Cocktail and Produce Wash. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 1336–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]