ElastoMeric Infusion Pumps for Hospital AntibioTICs (EMPHATIC): A Feasibility Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Primary Outcome—Feasibility

2.2. Secondary Outcomes

2.2.1. Clinical Cure

2.2.2. Adverse Events

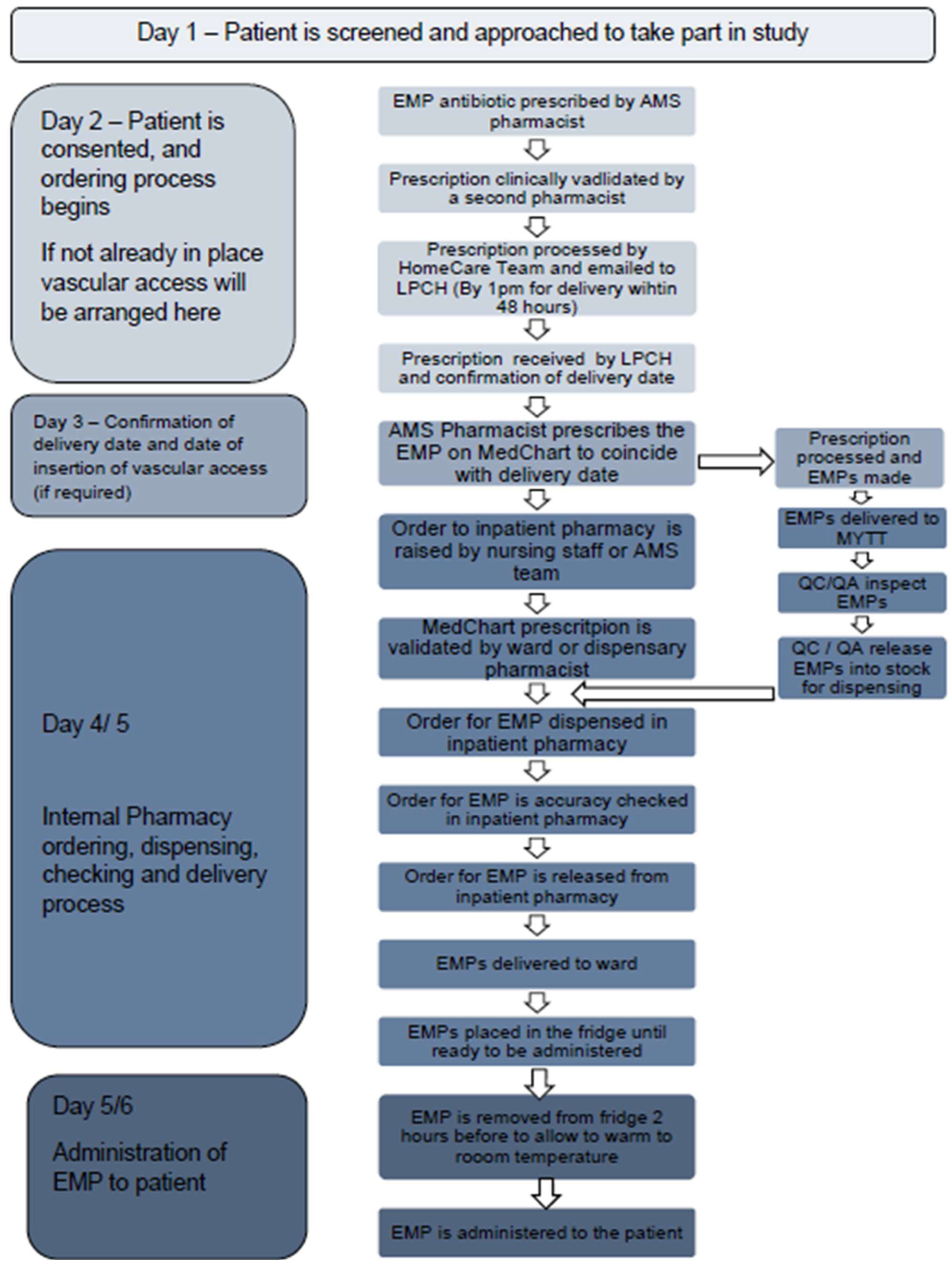

2.2.3. Procurement Process

2.2.4. Administration

2.2.5. Costs Analysis

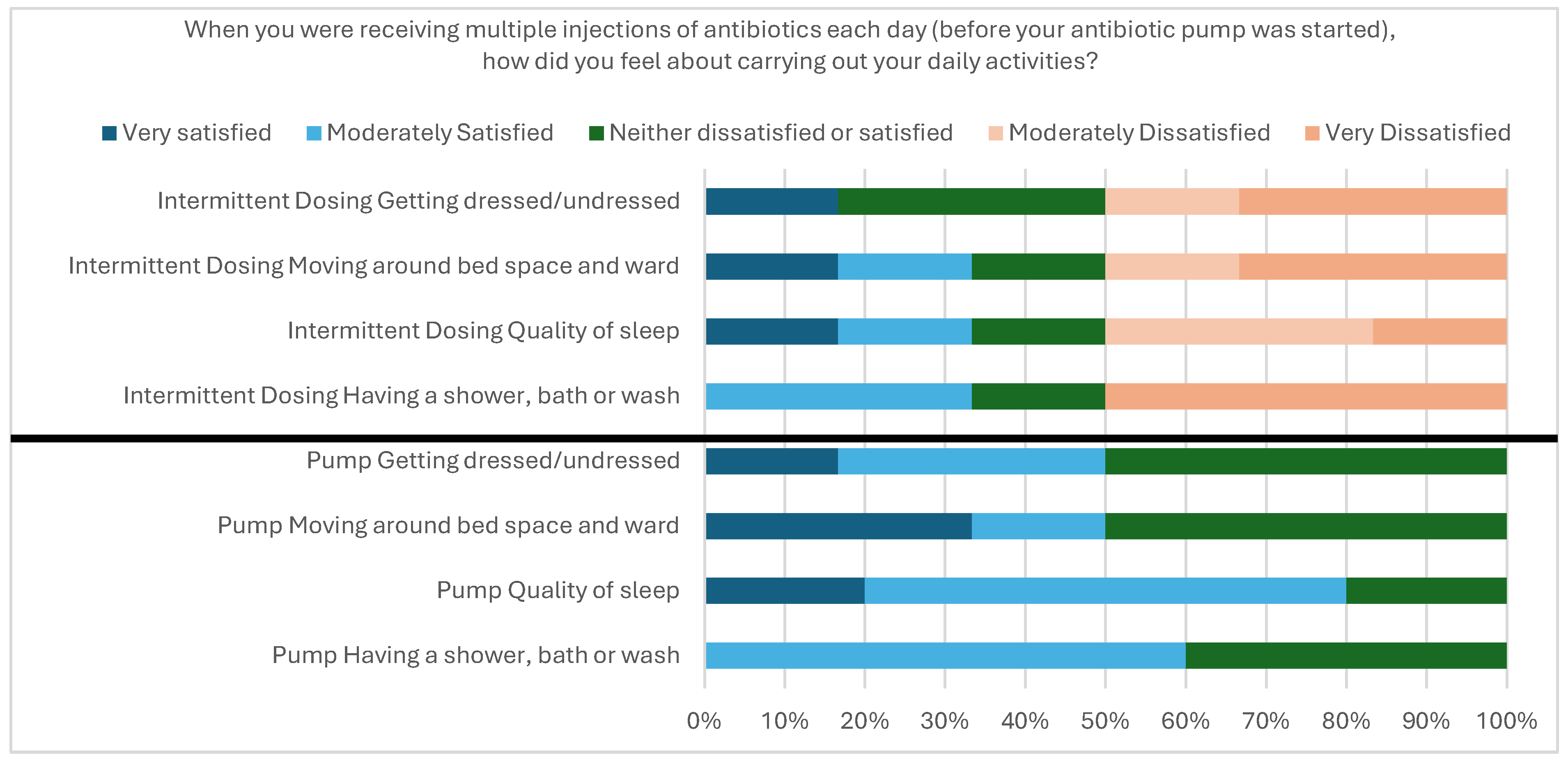

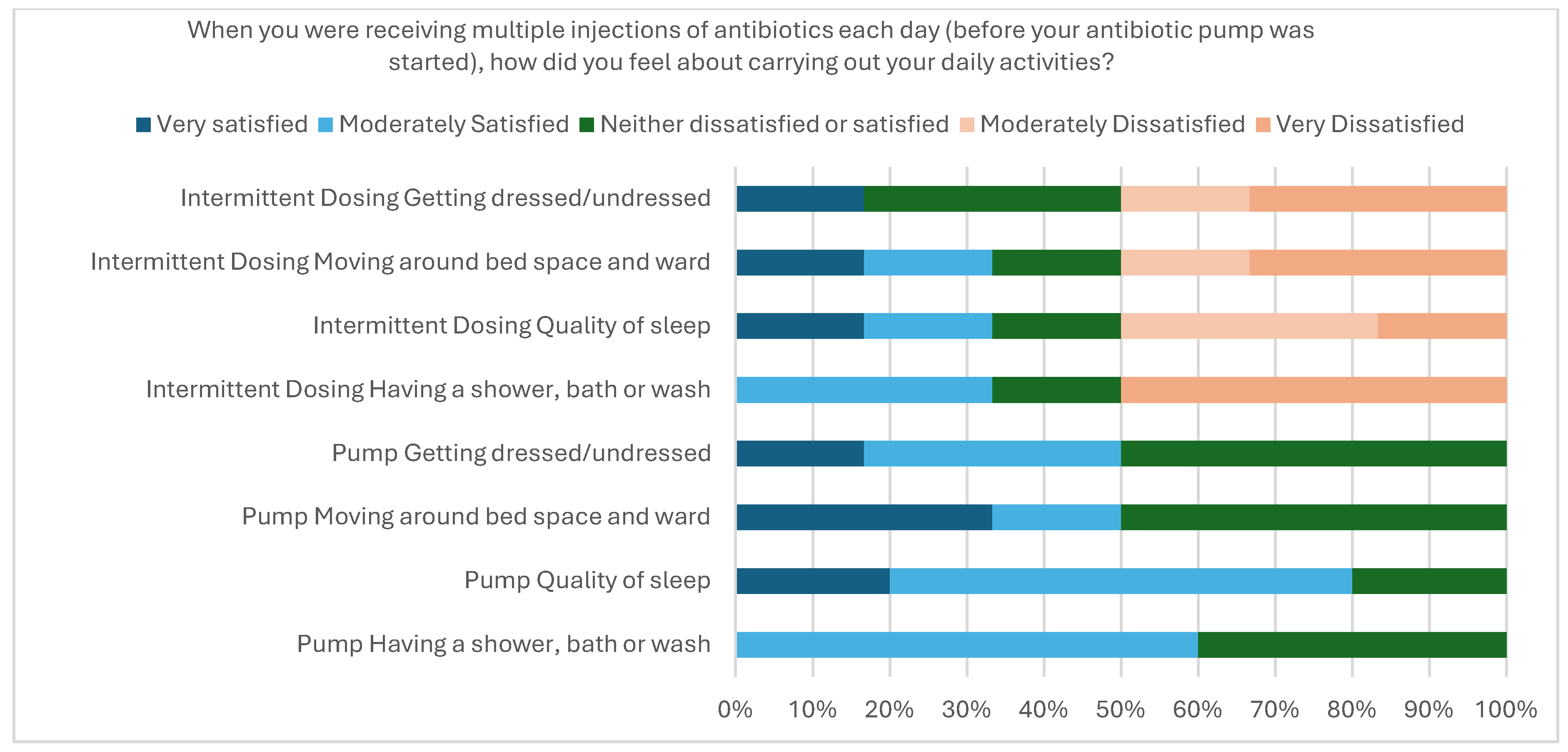

2.2.6. User Acceptability

2.2.7. Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Analysis [19]

Innovation Characteristics

Outer Setting—This Is the Setting in Which the Inner Setting Is Based: In This Case National and Local NHS Health Systems

Inner Domain—This Is the Setting Were the Innovation Takes Place: In This Case the Individual NHS Trust/Wards

Project Characteristics

Implementation Process

3. Discussion

4. Limitations

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Primary Objective

5.2. Secondary Objectives

- (a)

- To describe the antibiotic pathway for each patient;

- (b)

- To measure early termination of the planned period of IV antibiotics (including reason);

- (c)

- To evaluate user acceptability (medical, pharmacy, nursing) using a survey;

- (d)

- To measure antibiotic prescribing costs, including costs of ancillary items (IV giving sets, wipes, flushes, diluents);

- (e)

- To measure residual volume remaining in the pumps at the end of the infusion;

- (f)

- To measure the ordering and procurement process parameters;

- (g)

- To measure serious adverse events, including Clostridioides difficile diarrhea and death;

- (h)

- To measure intravascular access complications, including infection, thrombosis and line blockage;

- (i)

- To identify the barriers and facilitators to implementation.

5.3. Recruitment

5.4. Measures and Data Collection

- Demographic and clinical data were extracted from the hospitals’ electronic medical records (PPM+, version RC22.04.01—RC22.12.12, Leeds Teaching Hospitals, Leeds, UK) for each patient at baseline.

- A literature-informed patient feedback survey (see additional file 1) was developed by the study team that included co-author JT, a patient and a public involvement representative at the Trust [40]. Each patient was asked to complete the survey toward the end of their planned course of antibiotics via the EMP. The nursing feedback survey (see additional file 2) contained questions relating to training, information, administration, issues and overall experience.

- Intermittent dosing and EMP costs (inc. VAT) were calculated and compared, including giving sets, wipes, flushes, diluents and delivery. Due to commercial sensitivity, only the difference in cost between intermittent dosing and EMPs per day was reported. The costs used were 2022/23 prices. Staff costs were estimated based on costings by NHS England for nursing staff of GBP 18.19 per hour [47].

- Residual fluid volume in the EMPs was measured manually by removing the remaining solution, with a margin of error provided by Lloyds Pharmacy Clinical Homecare (LPCH, Coventry, UK) of 15% (36 mL) of a 240 mL EMP.

- Number of patients screened compared with those recruited.

- Clinical cure, defined as the resolution of symptoms and completion of antimicrobial therapy, which was assessed by the hospital medical consultant.

- Mortality at 30 and 90 days.

- Reliability of procurement, including time taken for delivery and any delays.

- Missed or delayed doses.

- Nursing time to administer.

- Requirement of intravascular devices.

- Difference in cost between EMPs and standard treatment (including ancillary items such as IV giving sets, wipes, flushes and diluents).

- Adverse events related to antibiotics, including blood dyscrasias, serum sickness, allergies, Clostridioides difficile diarrhea and death.

- Line-related adverse events including blockage, thrombosis and infection.

5.5. Data Analysis

5.6. EMP Procurement and Administration

5.7. Training

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EMP | Elastomeric infusion pump |

| OPAT | Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy |

| CFIR | Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research |

| IV | Intravenous |

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| M | Male |

| F | Female |

| AF | Atrial Fibrillation |

| IHD | Ischemic Heart Disease |

| GORD | Gastro Esophageal Reflux Disease |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| PMR | Polymyalgia Rheumatica |

| CCF | Congestive Cardiac Failure |

| IBS | Irritable Bowel Syndrome |

Appendix A

| ID | Microbiology | EMP Antibiotic | EMP Dose/24 h | Duration of Initial Antibiotics Prior to EMP (Days) | EMP Planned Duration (Days) | EMP Actual Duration (Days) | Total Duration of Initial and EMP Antibiotics (Days) | Completion of Full EMP Course | Reason for Not Completing | Additional Antibiotics Alongside EMP | Length of Stay (Days) | Microbiology/Clinical Cure | 30-Day Mortality? (Date of Diagnosis) | 90-Day Mortality? (Date of Diagnosis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Blood culture—Staphylococcus aureus | Flucloxacillin | 12 g | 3 | 7 | 3 | 7 | No | Adverse effects—deranged liver function | Rifampicin 600 mg BD Po (4 days) Changed to Linezolid 600 mg BD and Ciprofloxacin 250 mg BD | 36 | No | No | Yes |

| 2 | Blood culture—Staphylococcus aureus | Flucloxacillin | 12 g | 30 | 29 | 29 | 50 | Yes | N/A | Rifampicin 450 mg BD Po (50 days) | 68 | No | No | No |

| 3 | No positive microbiology | Flucloxacillin | 8 g | 22 | 21 | 21 | 42 | Yes | N/A | N/A | 87 | No | No | Yes |

| 4 | Blood culture—Staphylococcus aureus | Flucloxacillin | 8 g | 6 | 6 | 6 | 13 | Yes | OPAT discharge | Rifampicin 600 mg BD IV (5 days) | 16 | Yes | No | No |

| 5 | Blood culture—Staphylococcus aureus | Piperacillin/ Tazobactam | 13.5 g | 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | No | Switched to intermittent dosing | N/A | 100 | Yes | No | No |

| 6 | Blood culture—Staphylococcus aureus | Flucloxacillin | 12 g | 1 | 21 | 1 | 8 | No | Change of treatment | Changed to IV Rifampicin 600 mg BD and Daptomycin 500 mg IV | 37 | Yes | No | No |

| 7 | Blood culture—Streptococcus mutans | Benzylpenicillin | 7.2 g | 1 | 8 | 2 | 20 | No | Patient withdrew | N/A | 49 | Yes | No | No |

| 8 | Blood culture—Streptococcus salivarius | Benzylpenicillin | 7.2 g | 3 | 3 | 3 | 16 | Yes | OPAT discharge | N/A | 14 | Yes | No | No |

| 9 | Blood culture—Streptococcus oralis | Benzylpenicillin | 7.2 g | 22 | 22 | 22 | 43 | Yes | N/A | Clarithromycin 500 mg BD Po (5 days) Then Ciprofloxacin 400 mg IV BD Po (5 days) | 71 | Yes | No | Yes |

| Number of Days Treatment with EMP | EMP Cost (Excluding Consumables) | Consumables Cost | EMP Cost (Including Consumables) | EMP Cost per Day (Including Consumables) | Average Cost of EMP per Day (Including Consumables) | Nursing Cost to Administer | Total EMP Cost per Day (Including, Drug, Consumables and Nursing Costs) | Average Total EMP Cost per Day (Including, Drug, Consumables and Nursing Costs) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flucloxacillin 8 g/24 h | 32 | GBP 55.59 | GBP 63.27 (GBP 51.78–GBP 88.12) | GBP 3.33 | GBP 58.92 | GBP 66.60 (GBP 55.11–GBP 91.45) | |||

| Flucloxacillin 12 g/24 h | 30 | GBP 51.78 | GBP 3.33 | GBP 55.11 | |||||

| Piperacillin/tazobactam 13.5 g/24 h | 5 | GBP 88.12 | GBP 3.33 | GBP 91.45 | |||||

| Benzylpenicillin 7.2 g/24 h | 27 | GBP 57.58 | GBP 3.33 | GBP 60.91 | |||||

| Totals | 94 | GBP 266.40 |

| Consumables | Cost of Consumables | Cost of Consumables per Pump |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium chloride 0.9% 2 × 10 mL flush | ||

| 2 × 10 mL luer lock syringes | ||

| 2 × filter needles | ||

| 4 × PDI wipes | ||

| PICC dressing (Changed weekly) | ||

| Needle free device (Changed weekly) | ||

| Total | GBP 0.68 |

| Intermittent Cost per Day (Including Consumables) | Nursing Cost to Administer per Day | Total EMP Cost per Day (Including, Drug, Consumables and Nursing Costs) | Average total EMP Cost per Day (Including, Drug, Consumables and Nursing Costs) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flucloxacillin 2 g, 6 hourly | GBP 12.68 | GBP 26.68 | GBP 58.92 | GBP 66.60 (GBP 55.11–GBP 91.45) |

| Flucloxacillin 2 g, 4 hourly | GBP 15.96 | GBP 40.02 | GBP 55.11 | |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam 13.5 g | GBP 10.06 | GBP 20.01 | GBP 91.45 | |

| Benzylpenicillin 7.2 g | GBP 39.60 | GBP 40.02 | GBP 60.91 | |

| Totals | GBP 266.40 |

| Nurse Cost | |

|---|---|

| Per hour | GBP 18.19 |

| Per minute (hourly rate/60) | GBP 0.30 |

| Number of Doses per Day | Nursing Time Required to Administer One Dose Treatment (Minutes) | Nursing Time Required to Administer a Full Day of Treatment (Minutes) | Cost of Nursing Time Required to Administer a Full Day of Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any EMP | 1 | 11 | 11 | GBP 3.33 |

| Flucloxacillin 2 g, 6 hourly | 4 | 22 | 88 | GBP 26.68 |

| Flucloxacillin 2 g, 4 hourly | 6 | 22 | 132 | GBP 40.02 |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam 13.5 g, 8 hourly | 3 | 22 | 66 | GBP 20.01 |

| Benzylpenicillin 1.2 g, every 6 h | 6 | 22 | 132 | GBP 40.02 |

References

- Naghavi, M.; Vollset, S.E.; Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Gray, A.P.; Wool, E.E.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Mestrovic, T.; Smith, G.; Han, C.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: A systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plachouras, D.; Kärki, T.; Hansen, S.; Hopkins, S.; Lyytikäinen, O.; Moro, M.L.; Reilly, J.; Zarb, P.; Zingg, W.; Kinross, P.; et al. Antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals: Results from the second point prevalence survey (PPS) of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use, 2016 to 2017. Eurosurveillance 2018, 23, 1800393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi Jenkins, D.A.; Postin, E.; Saidi, N.; Agravedi, N. Jabs to Tabs: A Time and Motion Study Investigaing Medicines Administration. In Proceedings of the FIS/HIS London, 2022, London, UK, 22–26 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Garratt, K. The NHS Workforce in England; House of Commons Library: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Nursing. Employment Survery 2021; Royal College of Nursing: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pascale Carayon, A.P.G. Nursing Workload and Patient Safety—A Human Factors Engineering Perspective. In Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses; Hughes, R.G., Ed.; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, J.G.; Fernandes, J.; Duarte, A.R.; Fernandes, S.M. β-Lactam Dosing in Critical Patients: A Narrative Review of Optimal Efficacy and the Prevention of Resistance and Toxicity. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, D.; Biliune, J.; Kayyali, R.; Ashton, J.; Brown, P.; McCarthy, T.; Vikman, E.; Barton, S.; Swinden, J.; Nabhani-Gebara, S. Evaluation of the performance of elastomeric pumps in practice: Are we under-delivering on chemotherapy treatments? Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2017, 33, 2153–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selway, P. Elastomeric pumps for symptom control medication in patients dying with COVID-19. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2021, 13, e53–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, A.L.N.; Patel, S.; Horner, C.; Green, H.; Guleri, A.; Hedderwick, S.; Snape, S.; Statham, J.; Wilson, E.; Gilchrist, M.; et al. Updated good practice recommendations for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) in adults and children in the UK. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 1, dlz026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voumard, R.; Gardiol, C.; Andre, P.; Arensdorff, L.; Cochet, C.; Boillat-Blanco, N.; Decosterd, L.; Buclin, T.; De Valliere, S. Efficacy and safety of continuous infusions with elastomeric pumps for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT): An observational study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 2540–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantis, S.; Dawudi, Y.; Cassard, B.; Longuet, P.; Lesprit, P.; Gauzit, R. Home intravenous antibiotherapy and the proper use of elastomeric pumps: Systematic review of the literature and proposals for improved use. Infect. Dis. Now 2021, 51, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipman, J.; Brett, S.J.; De Waele, J.J.; Cotta, M.O.; Davis, J.S.; Finfer, S.; Glass, P.; Knowles, S.; McGuinness, S.; Myburgh, J.; et al. A protocol for a phase 3 multicentre randomised controlled trial of continuous versus intermittent β-lactam antibiotic infusion in critically ill patients with sepsis: BLING III. Crit. Care Resusc. 2019, 21, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Aziz, M.H.; Sulaiman, H.; Mat-Nor, M.B.; Rai, V.; Wong, K.K.; Hasan, M.S.; Abd Rahman, A.N.; Jamal, J.A.; Wallis, S.C.; Lipman, J.; et al. Beta-Lactam Infusion in Severe Sepsis (BLISS): A prospective, two-centre, open-labelled randomised controlled trial of continuous versus intermittent beta-lactam infusion in critically ill patients with severe sepsis. Intensiv. Care Med. 2016, 42, 1535–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulhunty, J.M.; Roberts, J.A.; Davis, J.S.; Webb, S.A.; Bellomo, R.; Gomersall, C.; Shirwadkar, C.; Eastwood, G.M.; Myburgh, J.; Paterson, D.L.; et al. A Multicenter Randomized Trial of Continuous versus Intermittent β-Lactam Infusion in Severe Sepsis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 1298–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer-Jones, J.; Luxton, T.; Bond, S.E.; Sandoe, J. Feasibility, Effectiveness and Safety of Elastomeric Pumps for Delivery of Antibiotics to Adult Hospital Inpatients—A Systematic Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geerligs, L.; Rankin, N.M.; Shepherd, H.L.; Butow, P. Hospital-based interventions: A systematic review of staff-reported barriers and facilitators to implementation processes. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Reardon, C.M.; Widerquist, M.A.O.; Lowery, J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-K.; Rombach, I.; Zambellas, R.; Walker, A.S.; McNally, M.A.; Atkins, B.L.; Lipsky, B.A.; Hughes, H.C.; Bose, D.; Kümin, M.; et al. Oral versus Intravenous Antibiotics for Bone and Joint Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iversen, K.; Ihlemann, N.; Gill, S.U.; Madsen, T.; Elming, H.; Jensen, K.T.; Bruun, N.E.; Høfsten, D.E.; Fursted, K.; Christensen, J.J.; et al. Partial Oral versus Intravenous Antibiotic Treatment of Endocarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 380, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmasry, Y.; Kwok, M.; Heard, K. Exploring benefits of nurse filled antibiotic elastomeric devices In Proceedings of the National OPAT Conference Liverpool 2024, Liverpool, UK, 8 November 2024.

- Ware, L. Nurse-filled elastomerics—The Leeds experience. In Proceedings of the British Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC) Regional OPAT Workshops, Birmingham, UK, 21 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ahtela, E.; Oksi, J.; Porela, P.; Ekström, T.; Rautava, P.; Kytö, V. Trends in occurrence and 30-day mortality of infective endocarditis in adults: Population-based registry study in Finland. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, N.; Al-Ahmady, Z.S.; Beziere, N.S.; Ntziachristos, V.; Kostarelos, K. Monoclonal antibody-targeted PEGylated liposome-ICG encapsulating doxorubicin as a potential theranostic agent. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 482, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangenberg, M.; Mende, K.C.; Mohme, M.; Krätzig, T.; Viezens, L.; Both, A.; Rohde, H.; Dreimann, M. Influence of microbiological diagnosis on the clinical course of spondylodiscitis. Infection 2021, 49, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.J.; Hodson, J.; Brooks, H.L.; Rosser, D. Missed medication doses in hospitalised patients: A descriptive account of quality improvement measures and time series analysis. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2013, 25, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Härkänen, M.; Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K.; Murrells, T.; Rafferty, A.M.; Franklin, B.D. Medication administration errors and mortality: Incidents reported in England and Wales between 2007–2016. Res Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Patient Safety Agency. Reducing Harm from Omitted and Delayed Medicines in Hospital; National Patient Saftey Agency: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, K.L.; Harris-Brown, T.; Smits, E.J.; Legg, A.; Chatfield, M.D.; Paterson, D.L. The MOBILISE study: Utilisation of ambulatory pumps in the inpatient setting to administer continuous antibiotic infusions—A randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 40, 2505–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.A. Does the Dose Matter? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, S233–S237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiveaud, D.; Demazieres, V.; Lafont, J. Comparison of the performance of four elastomeric devices. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. Pract. 2005, 11, 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Teames, R.; Joyce, A.; Scranton, R.; Vick, C.; Nagaraj, N. Characterization of Device-Related Malfunction, Injury, and Death Associated with Using Elastomeric Pumps for Delivery of Local Anesthetics in the US Food and Drug Administration MAUDE Database. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 2020, 12, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skryabina, E.A.; Dunn, T.S. Disposable infusion pumps. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2006, 63, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sime, F.B.; Wallis, S.; Jamieson, C.; Hills, T.; Gilchrist, M.; Santillo, M.; Seaton, R.A.; Drummond, F.; Roberts, J. Evaluation of the stability of aciclovir in elastomeric infusion devices used for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2025, 32, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Cartelle, B.; Vicente-Oliveros, N.; Menendez-Conde, C.P.; Serrano, D.R.; Martin-Davila, P.; Fortun-Abete, J.; Leon-Gil, L.A.; Alvarez-Diaz, A. Antibiotic stability in portable elastomeric infusion devices: A systematic review. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2022, 79, 1355–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS Pharmaceutical Assurance Committee; NHS Pharmaceutical Research and Development Working Group. A Standard Protocol for Deriving and Assessment of Stability. Part 1—Aseptic Preparations (Small Molecules); NHS Pharmaceutical Assurance Committee: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Rubio, B.; del Valle-Moreno, P.; Herrera-Hidalgo, L.; Gutierrez-Valencia, A.; Luque-Marquez, R.; Lopez-Cortes, L.E.; Gutierrez-Urbon, J.M.; Luque-Pardos, S.; Fernandez-Polo, A.; Gil-Navarro, M.V. Stability of Antimicrobials in Elastomeric Pumps: A Systematic Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A.; Shanu, S.; Jamieson, C.; Santillo, M. Systematic review of the stability of antimicrobial agents in elastomeric devices for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy services based on NHS Yellow Cover Document standards. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2022, 29, 304–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J.G.; Ryan, M.K.; Ritchie, B.; Sluggett, J.K.; Sluggett, A.J.; Ralton, L.; Reynolds, K.J. Protocol for a randomised crossover trial to evaluate patient and nurse satisfaction with electronic and elastomeric portable infusion pumps for the continuous administration of antibiotic therapy in the home: The Comparing Home Infusion Devices (CHID) study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, G. Optimising patient safety when using elastomeric pumps to administer outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy. Br. J. Nurs. 2016, 25, S22–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.R.; Weiner, B.J.; Reeve, B.B.; Hofmann, D.A.; Christian, M.; Weinberger, M. Determining the predictors of innovation implementation in healthcare: A quantitative analysis of implementation effectiveness. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonken, L.; de Bruijn, G.-J.; Noordink, A.; Kremers, S.; Schneider, F. Barriers and facilitators of implementation of new antibacterial technologies in patient care: An interview study with orthopedic healthcare professionals at a university hospital. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, M.A.; Kelley, C.; Yankey, N.; Birken, S.A.; Abadie, B.; Damschroder, L. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS England. NHS Long Term Workforce Plan; NHS England: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). Transforming NHS Pharmacy Aseptic Services in England; DHSC: London, UK, 2020.

- Hand, K.; IVOS Financial Savings and Busines Case Rescources. NHS Futures. 2023. Available online: https://future.nhs.uk/A_M_R/view?objectId=42417840 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Unique ID | Age | Sex | Past Medical History | Weight (kg) | Vascular Access Device | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 64 | M | Aortic stenosis—Tissue aortic valve replacement November 2021, GORD, COPD, two previous hip replacements | 84.1 | 5 French dual lumen PICC line | Endocarditis |

| 2 | 66 | M | Gout, obesity, appendicectomy, PMR, asthma, chronic kidney disease (stage 2) | 140 | 4 French single lumen PICC line | Discitis/infected knee joint |

| 3 | 67 | F | COPD, AF, CCF, type 2 diabetes mellitus, diabetic retinopathy, hypothyroid, diverticular disease, hypoadrenalism, hypertension, GORD | 54.8 | 5 French dual lumen PICC line | Osteomyelitis |

| 4 | 71 | M | Diverticulosis, asthma | 61.8 | 5 French dual lumen PICC line | Discitis |

| 5 | 59 | F | Type 2 diabetes mellitus, previous decompression and fusion surgery at L3/L4, osteoarthritis, hip replacement, recurrent osteomyelitis (right hallux), chronic pancreatitis, IBS, anxiety and depression, alcoholic fatty liver disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetic neuropathy, duodenitis | 65 | 3 French single lumen midline | Discitis |

| 6 | 54 | M | Hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, CCF, mitral regurgitation, osteoarthritis, recurrent cellulitis | 130 | 4 French single lumen PICC line | Endocarditis |

| 7 | 68 | M | Diverticulosis, mitral regurgitation, psoriasis, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus | 63.8 | Single lumen PICC line | Endocarditis |

| 8 | 63 | M | Hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus | 71.5 | 4 French single lumen PICC line | Endocarditis |

| 9 | 78 | M | Aortic valve replacement 2012, IHD, AF, pacemaker, type 2 diabetes mellitus | Unable to assess | 5 French single lumen PICC line | Endocarditis |

| Average Costs per Day | Difference Between EMP and Intermittent Dosing Costs per Day (Excluding Delivery Charges) | Difference Between EMP and Intermittent Dosing Costs per Day (with Delivery Charges Included) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EMP (including drug, consumables and nursing costs) | GBP 66.60 (GBP 55.11–GBP 91.45) | GBP 10.45 (GBP −18.71 to GBP 61.38) | GBP 32.50 (GBP 3.35–GBP 83.44) |

| Intermittent dosing (including drug, consumables and nursing costs) | GBP 56.15 (GBP 30.07–GBP 79.62) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spencer-Jones, J.J.; Bond, S.E.; Walker, N.; Lee-Milner, J.; Thompson, J.; Mustapha, D.; Sadiq, A.; Guleri, A.; Sarma, J.B.; Breen, L.; et al. ElastoMeric Infusion Pumps for Hospital AntibioTICs (EMPHATIC): A Feasibility Study. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111122

Spencer-Jones JJ, Bond SE, Walker N, Lee-Milner J, Thompson J, Mustapha D, Sadiq A, Guleri A, Sarma JB, Breen L, et al. ElastoMeric Infusion Pumps for Hospital AntibioTICs (EMPHATIC): A Feasibility Study. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(11):1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111122

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpencer-Jones, Joseph J., Stuart E. Bond, Nicola Walker, Jade Lee-Milner, Julie Thompson, Damilola Mustapha, Annam Sadiq, Achyut Guleri, Jayanta B. Sarma, Liz Breen, and et al. 2025. "ElastoMeric Infusion Pumps for Hospital AntibioTICs (EMPHATIC): A Feasibility Study" Antibiotics 14, no. 11: 1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111122

APA StyleSpencer-Jones, J. J., Bond, S. E., Walker, N., Lee-Milner, J., Thompson, J., Mustapha, D., Sadiq, A., Guleri, A., Sarma, J. B., Breen, L., & Sandoe, J. A. T. (2025). ElastoMeric Infusion Pumps for Hospital AntibioTICs (EMPHATIC): A Feasibility Study. Antibiotics, 14(11), 1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111122