Impact of ESKAPE Pathogens on Bacteremia: A Three-Year Surveillance Study at a Major Hospital in Southern Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Prevalence of BSIs in Studied Patients

2.2. Prevalence of Antimicrobial Resistance among Pathogens Identified in BSIs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Collection

4.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

4.3. Bacterial Culture and Identification

4.4. Antibiotic Susceptibility Assays

4.5. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hugonnet, S.; Sax, H.; Eggimann, P.; Chevrolet, J.C.; Pittet, D. Nosocomial bloodstream infection and clinical sepsis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, R.M.; Wolk, D.M. Bloodstream Infections. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 653–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, M.; Al-Hasan, M.N. Overall burden of bloodstream infection and nosocomial bloodstream infection in North America and Europe. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schechner, V.; Wulffhart, L.; Temkin, E.; Feldman, S.F.; Nutman, A.; Shitrit, P.; Schwaber, M.J.; Carmeli, Y. One-year mortality and years of potential life lost following bloodstream infection among adults: A nation-wide population based study. Lancet Reg. Health–Eur. 2022, 23, 100511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoofi, S.; Pashazadeh Kan, F.; Rafiei, S.; Hosseinipalangi, Z.; Noorani Mejareh, Z.; Khani, S.; Abdollahi, B.; Seyghalani Talab, F.; Sanaei, M.; Zarabi, F.; et al. Global prevalence of nosocomial infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0274248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità; EpiCentro—L’epidemiologia per la Sanità Pubblica. Rapporto CRE—I Dati 2022. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/antibiotico-resistenza/cre-dati (accessed on 27 July 2024).

- Dadgostar, P. Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications and Costs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 3903–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratia, C.; Soengas, R.G.; Soto, S.M. Gold-Derived Molecules as New Antimicrobial Agents. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 846959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Farmaco, A.I. The Medicines Utilisation Monitoring Centre. In National Report on Antibiotics Use in Italy; Italian Medicines Agency: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Arbune, M.; Gurau, G.; Niculet, E.; Iancu, A.V.; Lupasteanu, G.; Fotea, S.; Vasile, M.C.; Tatu, A.L. Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance of ESKAPE Pathogens over Five Years in an Infectious Diseases Hospital from South-East of Romania. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 2369–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, L.B. Federal funding for the study of antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: No ESKAPE. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 197, 1079–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santajit, S.; Indrawattana, N. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 2475067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marturano, J.E.; Lowery, T.J. ESKAPE Pathogens in Bloodstream Infections Are Associated with Higher Cost and Mortality but Can Be Predicted Using Diagnoses Upon Admission. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6, ofz503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance in Europe. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/351141/9789289056687-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance in Europe 2023–2021 Data. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/antimicrobial-resistance-surveillance-europe-2023-2021-data (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Verway, M.; Brown, K.A.; Marchand-Austin, A.; Diong, C.; Lee, S.; Langford, B.; Schwartz, K.L.; MacFadden, D.R.; Patel, S.N.; Sander, B.; et al. Prevalence and Mortality Associated with Bloodstream Organisms: A Population-Wide Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2022, 60, e0242921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrei, A.I.; Popescu, G.A.; Popoiu, M.A.; Mihai, A.; Talapan, D. Changes in Use of Blood Cultures in a COVID-19-Dedicated Tertiary Hospital. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mormeneo Bayo, S.; Palacian Ruiz, M.P.; Moreno Hijazo, M.; Villuendas Uson, M.C. Bacteremia during COVID-19 pandemic in a tertiary hospital in Spain. Enfermedades Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2022, 40, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslan, D.Z.; Crane, S.J.; Steckelberg, J.M.; Cockerill, F.R., 3rd; St Sauver, J.L.; Wilson, W.R.; Baddour, L.M. Age- and sex-associated trends in bloodstream infection: A population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohus, R.M.; Gustad, L.T.; Furberg, A.S.; Moen, M.K.; Liyanarachi, K.V.; Askim, A.; Asberg, S.E.; DeWan, A.T.; Rogne, T.; Simonsen, G.S.; et al. Explaining sex differences in risk of bloodstream infections using mediation analysis in the population-based HUNT study in Norway. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontula, K.S.K.; Skogberg, K.; Ollgren, J.; Järvinen, A.; Lyytikäinen, O. Population-Based Study of Bloodstream Infection Incidence and Mortality Rates, Finland, 2004–2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 2560–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawry, L.L.; Lugo-Robles, R.; McIver, V. Improvements to a framework for gender and emerging infectious diseases. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021, 99, 682–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliore, L.; Nicoli, V.; Stoccoro, A. Gender Specific Differences in Disease Susceptibility: The Role of Epigenetics. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiros-Roldan, E.; Sottini, A.; Natali, P.G.; Imberti, L. The Impact of Immune System Aging on Infectious Diseases. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, H.F.; Azevedo, J.; Silva, G.E.O.; Amorim, A.M.L.; de Roma, L.R.C.; Arraes, A.C.P.; Gouveia, E.L.; Reis, M.G.; Mendes, A.V.; de Oliveira Silva, M.; et al. Bloodstream infections caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria: Epidemiological, clinical and microbiological features. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licata, F.; Quirino, A.; Pepe, D.; Matera, G.; Bianco, A.; Collaborative, G. Antimicrobial Resistance in Pathogens Isolated from Blood Cultures: A Two-Year Multicenter Hospital Surveillance Study in Italy. Antibiotics 2020, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santella, B.; Folliero, V.; Pirofalo, G.M.; Serretiello, E.; Zannella, C.; Moccia, G.; Santoro, E.; Sanna, G.; Motta, O.; De Caro, F.; et al. Sepsis-A Retrospective Cohort Study of Bloodstream Infections. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccella, M.; Santella, B.; Pagliano, P.; De Filippis, A.; Casolaro, V.; Galdiero, M.; Borrelli, A.; Capunzo, M.; Boccia, G.; Franci, G. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Enterococcus Species: A Retrospective Cohort Study in Italy. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, B.P.; Barber, K.E.; Chastain, D.B. Treatment decisions in VRE bacteraemia: A survey of infectious diseases pharmacists. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 5, dlad063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net)—Annual Epidemiological Report for 2022. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/AER-antimicrobial-resistance.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Daneman, N.; Fridman, D.; Johnstone, J.; Langford, B.J.; Lee, S.M.; MacFadden, D.M.; Mponponsuo, K.; Patel, S.N.; Schwartz, K.L.; Brown, K.A. Antimicrobial resistance and mortality following E. coli bacteremia. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 56, 101781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.; Sullivan, B.; Dowsey, A.W.; Jones, K.; Beck, C.R. Epidemiology of Escherichia coli bloodstream infection antimicrobial resistance trends across South West England during the first 2 years of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic response. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, A.; Gutierrez, V.P.; Gomez, E.; Mon, A.M.; Sarmiento, C.M.; Khalid, A.; Polishchuk, S.; Al-Khateeb, M.; Yankulova, B.; Yusuf, M.; et al. Bloodstream infections in hospitalized patients before and during the COVID-19 surge in a community hospital in the South Bronx. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 116, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIFA. Agenzia Italiana Del Farmaco Terapia Mirata Delle Infezioni Causate da Batteri Gram Negativi Resistenti a Multipli Antibiotici. Available online: https://www.aifa.gov.it/documents/20142/1787183/AIFA-OPERA_Raccomandazioni_pazienti_ospedalizzati.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Gandra, S.; Mojica, N.; Klein, E.Y.; Ashok, A.; Nerurkar, V.; Kumari, M.; Ramesh, U.; Dey, S.; Vadwai, V.; Das, B.R.; et al. Trends in antibiotic resistance among major bacterial pathogens isolated from blood cultures tested at a large private laboratory network in India, 2008–2014. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 50, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremeskel, L.; Teklu, T.; Kasahun, G.G.; Tuem, K.B. Antimicrobial resistance pattern of Klebsiella isolated from various clinical samples in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, X.; Stalsby Lundborg, C.; Sun, X.; Hu, X.; Dong, H. Clinical and Economic Impact of Third-Generation Cephalosporin-Resistant Infection or Colonization Caused by Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: A Multicenter Study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrakis, V.; Panopoulou, M.; Rafailidis, P.; Lemonakis, N.; Lazaridis, G.; Terzi, I.; Papazoglou, D.; Panagopoulos, P. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Antimicrobial Resistance and Management of Bloodstream Infections. Pathogens 2023, 12, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Istituto Superiore di Sianità. Rapporto AR-ISS—I Dati 2022. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/antibiotico-resistenza/ar-iss-rapporto-klebsiella-pneumoniae (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Tabah, A.; Koulenti, D.; Laupland, K.; Misset, B.; Valles, J.; Bruzzi de Carvalho, F.; Paiva, J.A.; Cakar, N.; Ma, X.; Eggimann, P.; et al. Characteristics and determinants of outcome of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections in intensive care units: The EUROBACT International Cohort Study. Intensive Care Med. 2012, 38, 1930–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, A.; Bassetti, M.; Ceccarelli, G.; Carannante, N.; Losito, A.R.; Bartoletti, M.; Corcione, S.; Granata, G.; Santoro, A.; Giacobbe, D.R.; et al. Bloodstream infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: Clinical features, therapy and outcome from a multicenter study. J. Infect. 2019, 79, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizimungu, O.; Crook, P.; Babane, J.F.; Bitunguhari, L. The prevalence and clinical context of antimicrobial resistance amongst medical inpatients at a referral hospital in Rwanda: A cohort study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2024, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIFA, Agenzia Italiana Del Farmaco. AIFA Publishes Recommendations on Targeted Therapy of Resistant Infections. Available online: https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/-/aifa-pubblica-le-raccomandazioni-sulla-terapia-mirata-delle-infezioni-resistenti (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Serretiello, E.; Manente, R.; Dell’Annunziata, F.; Folliero, V.; Iervolino, D.; Casolaro, V.; Perrella, A.; Santoro, E.; Galdiero, M.; Capunzo, M.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Lu, L.; Zhao, K.L.; Zeng, Q.L. Resistance Transition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in SARS-CoV-2-Uninfected Hospitalized Patients in the Pandemic. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 6717–6724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

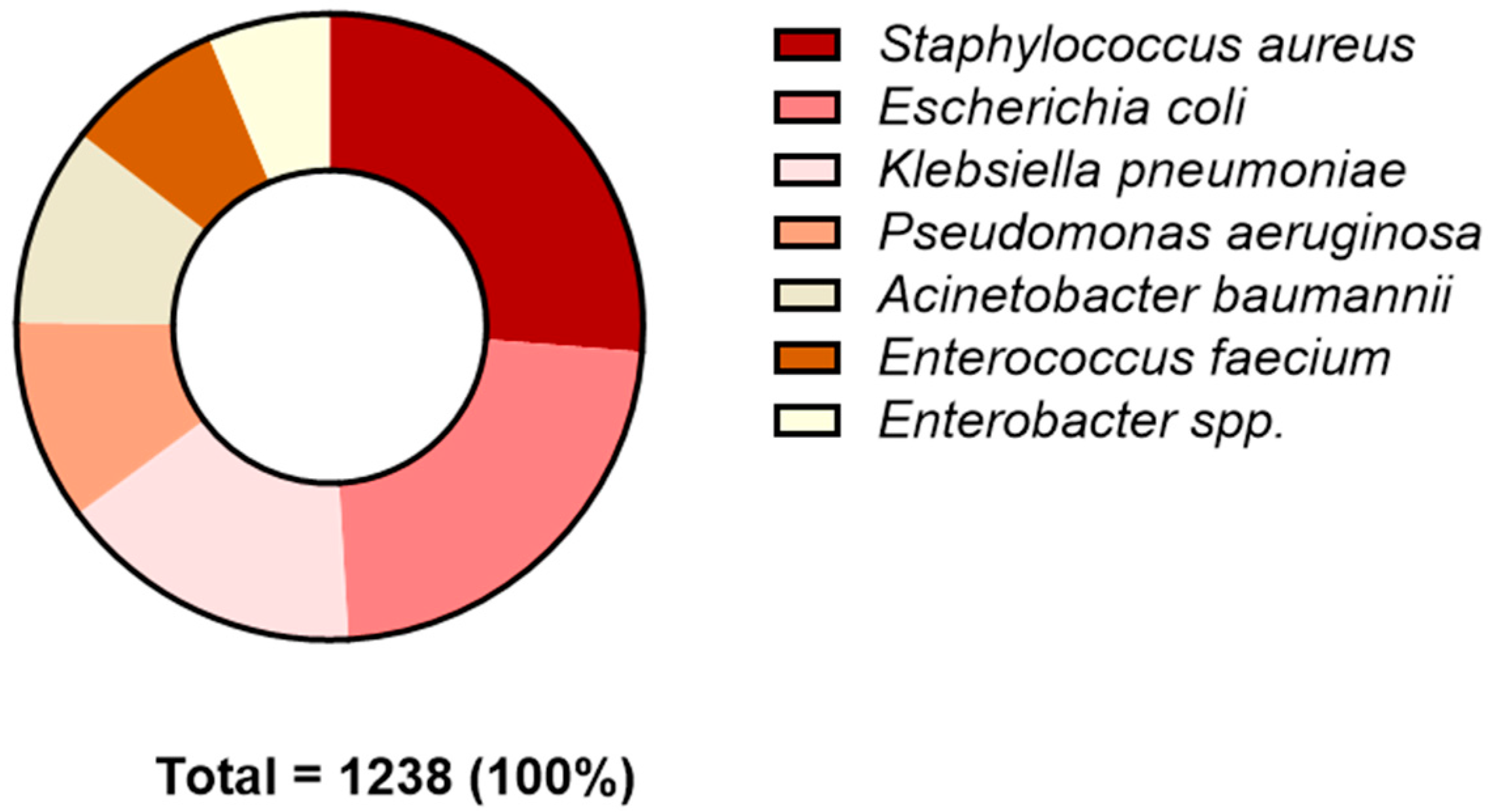

| Pathogen | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Pathogenic bacteria | 3197 |

| ESKAPE pathogen | 1238 (38.7) |

| Other pathogen | 1959 (61.3) |

| Gender | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | TOT | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 225 | 295 | 317 | 837 | 40.1 |

| Male | 348 | 441 | 461 | 1250 | 59.9 |

| Total | 573 | 736 | 778 | 2087 | |

| Age (years) | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | TOT | % |

| 0–19 | 33 | 38 | 33 | 104 | 5.0 |

| 20–39 | 39 | 35 | 29 | 103 | 4.9 |

| 40–59 | 129 | 131 | 146 | 406 | 19.5 |

| ≥60 | 372 | 532 | 408 | 1474 | 70.6 |

| Total | 573 | 736 | 778 | 2087 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 2020 (R%) | 2021 | 2022 | p-Value |

| Amikacin | 78.8 (41) | 88.9 (32) | 87.5 (35) | 0.233 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 98.0 (50) | 94.4 (34) | 94.9 (37) | 0.422 |

| Colistin | 2.0 (1) | 2.9 (1) | 2.8 (1) | 0.820 |

| Gentamicin | 94.1 (48) | 94.4 (34) | 89.7 (35) | 0.444 |

| Imipenem | 95.7 (44) | 94.4 (34) | 94.9 (37) | 0.862 |

| Meropenem | 96.1 (49) | 100 (19) | 92.5 (37) | 0.448 |

| Tobramycin | 93.3 (42) | 94.3 (33) | 88.9 (32) | 0.479 |

| Trimethoprim/sulfam | 94.1 (48) | 91.7 (33) | 87.2 (34) | 0.252 |

| Escherichia coli | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | p-Value |

| Amikacin | 0 (0) | 1.3 (1) | 1.6 (2) | 0.322 |

| Amoxicillin/clav. acid | 46.7 (28) | 49.3 (36) | 41.9 (54) | 0.435 |

| Cefepime | 33.9 (21) | 36.3 (29) | 30.2 (39) | 0.519 |

| Cefotaxime | 46.6 (34) | 37.0 (17) | 43.4 (56) | 0.751 |

| Ceftazidime | 39.7 (29) | 45.0 (36) | 34.1 (44) | 0.323 |

| Ceftazidime/avibactam | 0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 5.6 (7) | 0.020 |

| Ceftolozane/tazobactam | 3.8 (2) | 6.6 (4) | 7.2 (9) | 0.413 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 63.5 (47) | 57.5 (46) | 51.9 (67) | 0.107 |

| Colistin | 0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 3.2 (4) | 0.061 |

| Gentamicin | 31.5 (23) | 27.5 (22) | 19.4 (25) | 0.046 |

| Imipenem | 0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 1.6 (2) | 0.180 |

| Meropenem | 0 (0) | 1.7 (1) | 1.5 (2) | 0.359 |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 10.8 (8) | 16.0 (13) | 10.1 (13) | 0.725 |

| Tobramycin | 32.3 (20) | 32.4 (22) | 19.2 (24) | 0.032 |

| Trimethoprim/sulfam | 47.3 (35) | 37.5 (30) | 47.3 (61) | 0.826 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | p-Value |

| Amikacin | 35.8 (24) | 21.4 (12) | 20.8 (15) | 0.047 |

| Amoxicillin/clav. acid | 85.0 (51) | 69.6 (39) | 80.6 (58) | 0.602 |

| Cefepime | 74.5 (35) | 48.2 (27) | 65.3 (47) | 0.493 |

| Cefotaxime | 83.8 (57) | 65.2 (30) | 69.4 (50) | 0.056 |

| Ceftazidime | 82.4 (56) | 61.4 (35) | 70.8 (51) | 0.137 |

| Ceftazidime/avibactam | 11.4 (5) | 5.6 (3) | 9.9 (7) | 0.895 |

| Ceftolozane/tazobactam | 45.5 (20) | 49.1 (26) | 47.9 (34) | 0.828 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 82.4 (56) | 58.9 (33) | 63.9 (46) | 0.020 |

| Colistin | 32.3 (21) | 3.8 (2) | 7.0 (5) | <0.001 |

| Gentamicin | 43.3 (29) | 17.9 (10) | 33.3 (24) | 0.230 |

| Imipenem | 42.6 (20) | 24.1 (14) | 33.3 (24) | 0.406 |

| Meropenem | 57.4 (39) | 24.5 (12) | 36.0 (27) | 0.011 |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 67.6 (46) | 63.2 (36) | 73.6 (53) | 0.438 |

| Tobramycin | 63.6 (28) | 38.5 (20) | 43.7 (31) | 0.063 |

| Trimethoprim/sulfam | 45.6 (31) | 48.2 (27) | 47.2 (34) | 0.849 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | p-Value |

| Amikacin | 8.8 (3) | 4.2 (2) | 17.0 (8) | 0.170 |

| Cefepime | 26.9 (7) | 12.2 (6) | 36.2 (17) | 0.235 |

| Ceftazidime | 35.3 (12) | 18.8 (9) | 36.2 (17) | 0.774 |

| Ceftazidime/avibactam | 13.6 (3) | 7.7 (3) | 13.0 (6) | 0.902 |

| Ceftolozane/tazobactam | 22.7 (5) | 7.7 (3) | 13.0 (6) | 0.423 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 20.6 (7) | 33.3 (16) | 38.3 (18) | 0.098 |

| Colistin | 10.0 (3) | 2.3 (1) | 8.7 (4) | 0.975 |

| Imipenem | 18.5 (5) | 16.3 (8) | 34.0 (16) | 0.078 |

| Meropenem | 5.9 (2) | 21.4 (9) | 32.0 (16) | 0.004 |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 39.4 (13) | 29.2 (14) | 44.7 (21) | 0.521 |

| Tobramycin | 12.5 (3) | 9.1 (4) | 28.3 (13) | 0.046 |

| Enterococcus faecium | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | p-Value |

| Amoxicillin/clav. acid | 93.3 (14) | 100 (32) | 98.0 (48) | 0.491 |

| Ampicillin | 90.0 (18) | 97.0 (32) | 98.0 (48) | 0.158 |

| Ampicillin/sulbactam | 87.5 (7) | 90.9 (20) | 95.9 (47) | 0.466 |

| Quinupristin/dalfopristin | 12.5 (2) | 6.1 (2) | 2.0 (1) | 0.097 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 85.7 (6) | 100 (22) | 95.9 (47) | 0.580 |

| Imipenem | 90.0 (18) | 100 (33) | 98.0 (48) | 0.159 |

| Kanamycin high level | 81.3 (13) | 84.4 (27) | 100 (49) | 0.005 |

| Levofloxacin | 85.7 (6) | 100 (22) | 98.0 (48) | 0.238 |

| Linezolid | 14.3 (3) | 5.9 (2) | 4.1 (2) | 0.145 |

| Streptomycin high level | 75.0 (12) | 84.4 (27) | 89.6 (43) | 0.155 |

| Teicoplanin | 28.6 (6) | 23.5 (8) | 18.8 (9) | 0.355 |

| Tigecycline | 6.3 (1) | 6.3 (2) | 6.3 (3) | 0.997 |

| Vancomycin | 23.8 (5) | 22.9 (8) | 18.8 (9) | 0.595 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | p-Value |

| Fusidic acid | 2.4 (2) | 1.9 (2) | 7.4 (10) | 0.053 |

| Ceftaroline | 1.3 (1) | 0.9 (1) | 1.5 (1) | 0.871 |

| Daptomycin | 4.8 (4) | 2.8 (3) | 8.8 (12) | 0.146 |

| Erythromycin | 44.6 (37) | 51.0 (53) | 48.2 (66) | 0.679 |

| Gentamicin | 6.0 (5) | 5.7 (6) | 6.6 (9) | 0.844 |

| Levofloxacin | 35.7 (30) | 33.0 (35) | 34.6 (47) | 0.900 |

| Linezolid | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2.2 (3) | 0.070 |

| Mupirocin | 0 (0) | 1.9 (2) | 0.7 (1) | 0.748 |

| Oxacillin | 36.1 (30) | 36.2 (38) | 33.8 (46) | 0.702 |

| Benzylpenicillin | 80.7 (67) | 72.0 (77) | 69.9 (95) | 0.091 |

| Rifampicin | 6.0 (5) | 4.8 (5) | 7.4 (10) | 0.620 |

| Teicoplanin | 9.6 (8) | 10.4 (11) | 11.7 (16) | 0.624 |

| Tetracycline | 7.2 (6) | 2.9 (3) | 2.9 (4) | 0.147 |

| Tigecycline | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.7 (1) | 0.296 |

| Trimethoprim/sulfam | 1.2 (1) | 3.8 (4) | 3.7 (5) | 0.339 |

| Vancomycin | 1.2 (1) | 5.5 (6) | 12.5 (17) | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Prisco, M.; Manente, R.; Santella, B.; Serretiello, E.; Dell’Annunziata, F.; Santoro, E.; Bernardi, F.F.; D’Amore, C.; Perrella, A.; Pagliano, P.; et al. Impact of ESKAPE Pathogens on Bacteremia: A Three-Year Surveillance Study at a Major Hospital in Southern Italy. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13090901

De Prisco M, Manente R, Santella B, Serretiello E, Dell’Annunziata F, Santoro E, Bernardi FF, D’Amore C, Perrella A, Pagliano P, et al. Impact of ESKAPE Pathogens on Bacteremia: A Three-Year Surveillance Study at a Major Hospital in Southern Italy. Antibiotics. 2024; 13(9):901. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13090901

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Prisco, Mariagrazia, Roberta Manente, Biagio Santella, Enrica Serretiello, Federica Dell’Annunziata, Emanuela Santoro, Francesca F. Bernardi, Chiara D’Amore, Alessandro Perrella, Pasquale Pagliano, and et al. 2024. "Impact of ESKAPE Pathogens on Bacteremia: A Three-Year Surveillance Study at a Major Hospital in Southern Italy" Antibiotics 13, no. 9: 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13090901

APA StyleDe Prisco, M., Manente, R., Santella, B., Serretiello, E., Dell’Annunziata, F., Santoro, E., Bernardi, F. F., D’Amore, C., Perrella, A., Pagliano, P., Boccia, G., Franci, G., & Folliero, V. (2024). Impact of ESKAPE Pathogens on Bacteremia: A Three-Year Surveillance Study at a Major Hospital in Southern Italy. Antibiotics, 13(9), 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13090901