Antibiotic Prescribing Trends in Dentistry during Ten Years’ Period—Croatian National Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. General (Overall) Data

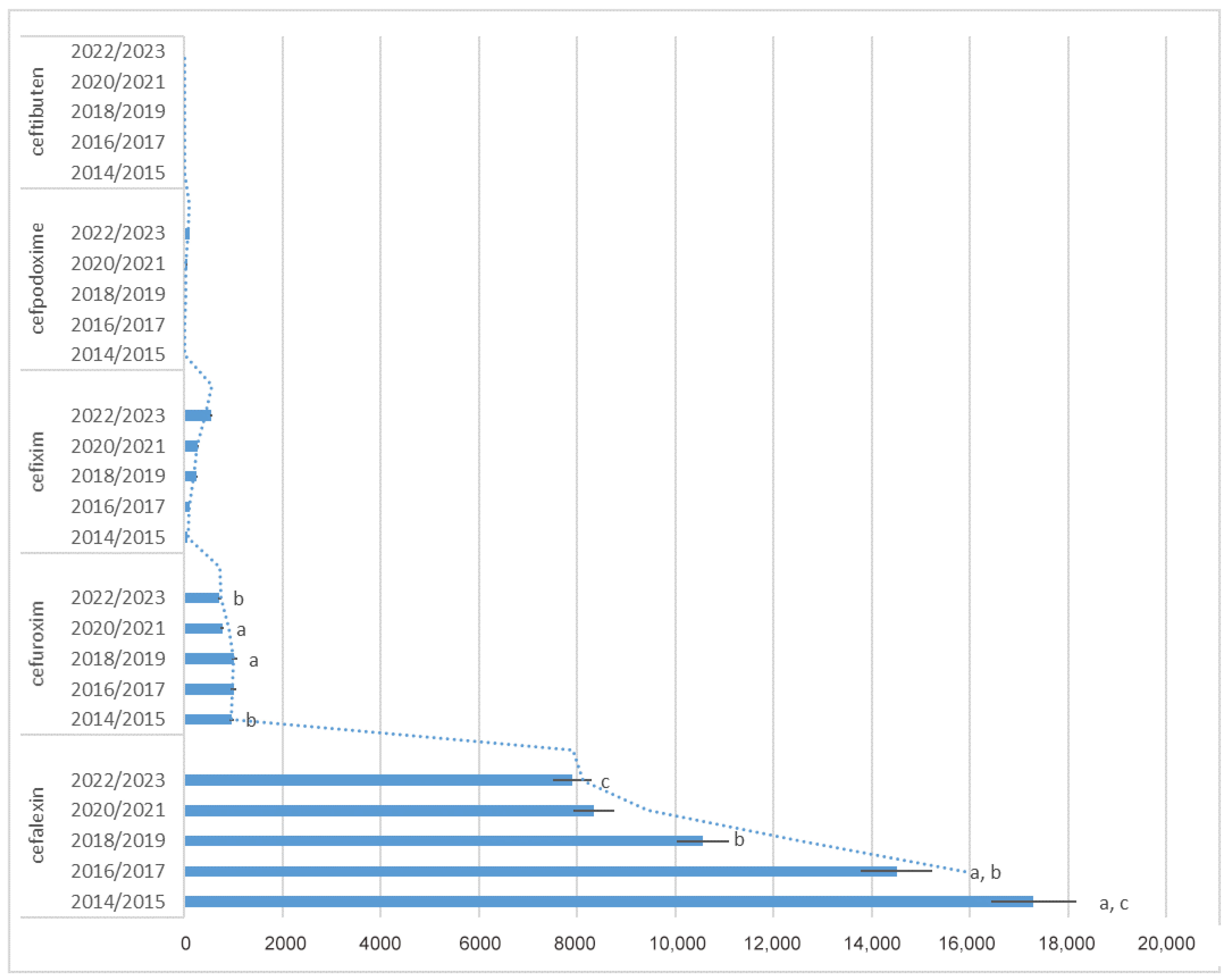

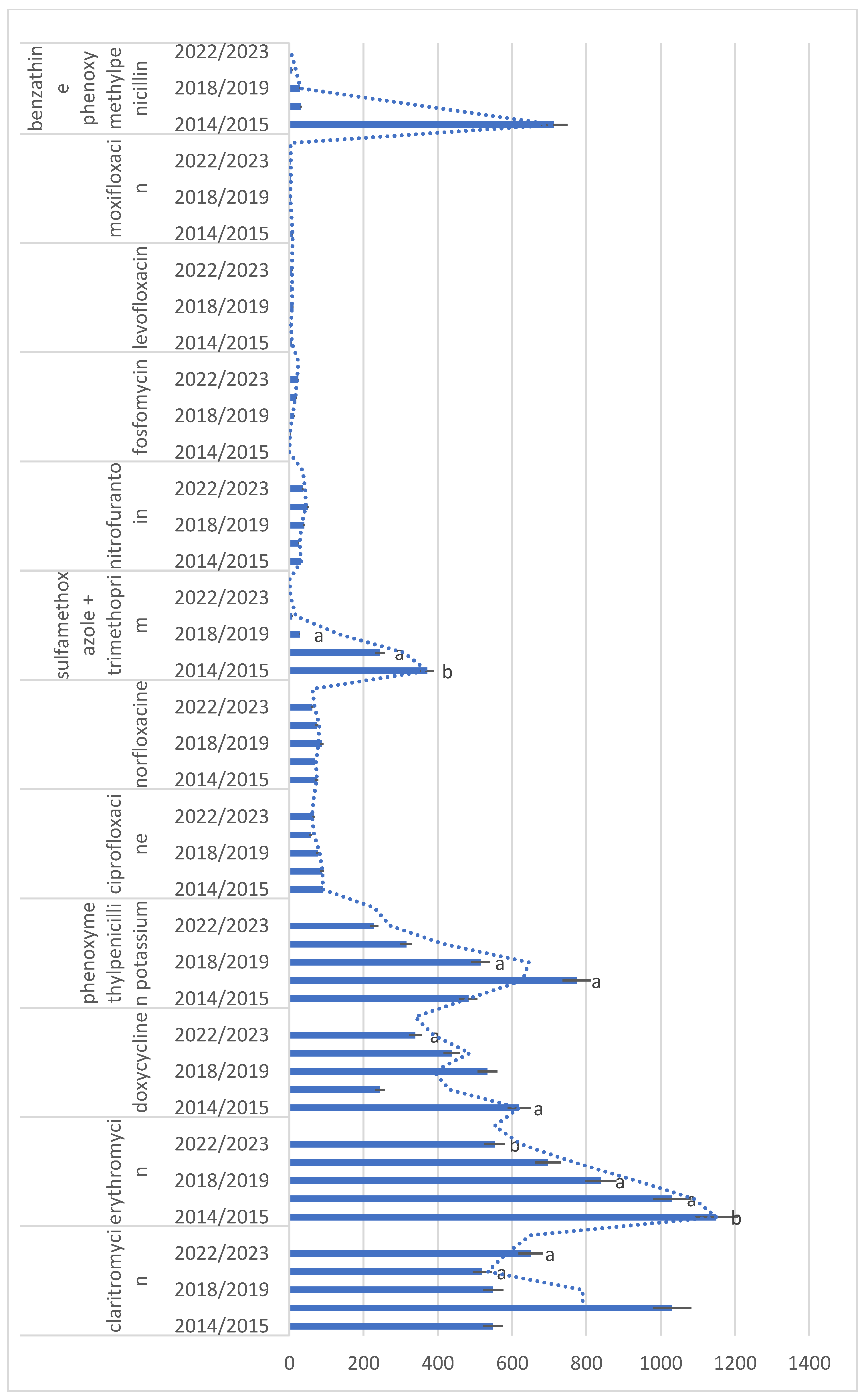

2.2. Antibiotic Utilization

2.3. Dentists Share in National Antibiotic Consumption

2.4. Changes in Utilization Trend

3. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Teughels, W.; Feres, M.; Oud, V.; Martín, C.; Matesanz, P.; Herrera, D. Adjunctive Effect of Systemic Antimicrobials in Periodontitis Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47 (Suppl. S22), 257–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Egea, J.J.; Gould, K.; Şen, B.H.; Jonasson, P.; Cotti, E.; Mazzoni, A.; Sunay, H.; Tjäderhane, L.; Dummer, P.M.H. European Society of Endodontology Position Statement: The Use of Antibiotics in Endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornhill, M.H.; Dayer, M.; Prendergast, B.D.; Lockhart, P.; Baddour, L. Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Dentistry. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 960–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romandini, M.; De Tullio, I.; Congedi, F.; Kalemaj, Z.; D’Ambrosio, M.; Laforí, A.; Quaranta, C.; Buti, J.; Perfetti, G. Antibiotic Prophylaxis at Dental Implant Placement: Which Is the Best Protocol? A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šutej, I.; Lepur, D.; Božić, D.; Pernarić, K. Medication Prescribing Practices in Croatian Dental Offices and Their Contribution to National Consumption. Int. Dent. J. 2021, 71, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roganović, J.; Barać, M. Rational Antibiotic Prescribing Is Underpinned by Dental Ethics Principles: Survey on Postgraduate and Undergraduate Dental Students’ Perceptions. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săndulescu, O.; Săndulescu, M. The 5Ds of Optimized Antimicrobial Prescription in Dental Medicine. Germs 2023, 13, 207–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Addressing Medicine Shortages in the EU 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2023%3A672%3AREV1 (accessed on 27 July 2024).

- Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Population Estimate. Available online: https://podaci.dzs.hr/en/statistics/population/population-estimate/ (accessed on 27 July 2024).

- Draganić, P.; Oštarčević, S.; Škribulja, M. Potrošnja Lijekova u Hrvatskoj 2017–2021; Agencija za Lijekove i Medicinske Proizvode-HALMED: Zagreb, Croatia, 2022.

- Šutej, I.; Lepur, D.; Bašić, K.; Šimunović, L.; Peroš, K. Changes in Medication Prescribing Due to COVID-19 in Dental Practice in Croatia-National Study. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimundić Munitić, M.; Šutej, I.; Ćaćić, N.; Tadin, A.; Balić, M.; Bago, I.; Poklepović Peričić, T. Knowledge and Attitudes of Croatian Dentists Regarding Antibiotic Prescription in Endodontics: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire-Based Study. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2021, 55, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, M.; Perković, I.; Romić, M.; Simeon, P.; Matijević, J.; Mehičić, G.P.; Krmek, S.J. The Pattern of Antibiotic Prescribing by Dental Practitioners in Zagreb, Croatia. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 23, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelovucic, R.; Par, M.; Rubcic, D.; Marovic, D.; Prskalo, K.; Tarle, Z. Antibiotic Prescription in Emergency Dental Service in Zagreb, Croatia—A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int. Dent. J. 2019, 69, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sović, J.; Šegović, S.; Tomasić, I.; Pavelić, B.; Šutej, I.; Anić, I. Antibiotic Administration Along with Endodontic Therapy in the Republic of Croatia: A Pilot Study. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2020, 54, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Egea, J.J.; Velasco-Ortega, E.; Torres-Lagares, D.; Velasco-Ponferrada, M.C.; Monsalve-Guil, L.; Llamas-Carreras, J.M. Pattern of Antibiotic Prescription in the Management of Endodontic Infections amongst Spanish Oral Surgeons. Int. Endod. J. 2010, 43, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deniz-Sungur, D.; Aksel, H.; Karaismailoglu, E.; Sayin, T.C. The Prescribing of Antibiotics for Endodontic Infections by Dentists in Turkey: A Comprehensive Survey. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 1715–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuculina, M.J.; Diaconu, O.A.; Madalina, C.; Gheorghiță, L.M.; Bătăiosu, M.; Dragomir, L.; Nicola, A.G.; Cumpătă, C.N.; Dăguci, C.; Turcu, A. An Observational Study: Use of Systemic Antibiotics for Endodontic Infections Treatment. J. Dent. Health Oral Res. 2022, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Domínguez, L.; López-Marrufo-Medina, A.; Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Jiménez-Sánchez, M.C.; Areal-Quecuty, V.; López-López, J.; Segura-Egea, J.J.; Martin-González, J. Antibiotics Prescription by Spanish General Practitioners in Primary Dental Care. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobac, M.; Otasevic, K.; Ramic, B.; Cvjeticanin, M.; Stojanac, I.; Petrovic, L. Antibiotic Prescribing Practices in Endodontic Infections: A Survey of Dentists in Serbia. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, D.; Baranto, G.; Lund, B.; Hultin, M. Antibiotic Utilization in Emergency Dental Care in Stockholm 2016: A Cross Sectional Study. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2022, 80, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousi, F.; Al Haroni, M.; Lie, S.A.; Lund, B. Antibiotic Prescriptions among Dentists across Norway and the Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudet, A.; Kichenbrand, C.; Pulcini, C.; Descroix, V.; Lesclous, P.; Thilly, N.; Clément, C.; Guillet, J. Antibiotic Use and Resistance: A Nationwide Questionnaire Survey among French Dentists. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 1295–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainjot, A.; D’Hoore, W.; Vanheusden, A.; Van Nieuwenhuysen, J.-P. Antibiotic Prescribing in Dental Practice in Belgium. Int. Endod. J. 2009, 42, 1112–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolksdorf, K.; Freytag, A.; Bleidorn, J.; Markwart, R. Antibiotic Use by Dentists in Germany: A Review of Prescriptions, Pathogens, Antimicrobial Resistance and Antibiotic Stewardship Strategies. Community Dent. Health 2022, 39, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teoh, L.; Hopcraft, M.; McCullough, M.; Manski-Nankervis, J.-A.; Biezen, R. Exploring the Appropriateness of Antibiotic Prescribing for Dental Presentations in Australian General Practice—A Pilot Study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 89, 1554–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanathan, S.; Yan, C.H.; Hubbard, C.; Calip, G.S.; Sharp, L.K.; Evans, C.T.; Rowan, S.; McGregor, J.C.; Gross, A.E.; Hershow, R.C.; et al. Changes in Antibiotic Prescribing by Dentists in the United States, 2012–2019. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2023, 44, 1725–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.; Teoh, L.; Hubbard, C.C.; Marra, F.; Patrick, D.M.; Mamun, A.; Campbell, A.; Suda, K.J. Patterns of Dental Antibiotic Prescribing in 2017: Australia, England, United States, and British Columbia (Canada). Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2022, 43, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M.; Giardino, I.; Carrasco-Sanz, A.; Somekh, E.; Levy, C. The Shortage of Amoxicillin: An Escalating Public Health Crisis in Pediatrics Faced by Several Western Countries. J. Pediatr. 2023, 257, 113321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, N.M.; Lee, B.R.; Kronman, M.P.; Smith, M.J.; Patel, S.J.; Olivero, R.; Wattles, B.A.; Herigon, J.; Wirtz, A.; El Feghaly, R.E. Ambulatory Amoxicillin Use for Common Acute Respiratory Infections during a National Shortage: Results from the SHARPS-OP Benchmarking Collaborative. Am. J. Infect. Control 2024, 52, 614–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khazanchi, R.; Brewster, R.; Butler, A.; O’Meara, D.; Bagchi, D.P.; Michelson, K. 1652. Impact of the 2022–2023 Amoxicillin Shortage on Antibiotic Prescribing for Acute Otitis Media: A Regression Discontinuity Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad500.1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Steps up Action to Prevent Shortages of Antibiotics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_3890 (accessed on 27 July 2024).

- Albrecht, H.; Schiegnitz, E.; Halling, F. Facts and Trends in Dental Antibiotic and Analgesic Prescriptions in Germany, 2012–2021. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradl, G.; Kieble, M.; Nagaba, J.; Schulz, M. Assessment of the Prescriptions of Systemic Antibiotics in Primary Dental Care in Germany from 2017 to 2021: A Longitudinal Drug Utilization Study. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjome, R.L.S.; Bjønnes, J.A.J.; Lygre, H. Changes in Dentists’ Prescribing Patterns in Norway 2005–2015. Int. Dent. J. 2021, 72, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Struyf, T.; Vandael, E.; Leroy, R.; Mertens, K.; Catry, B. Antimicrobial Prescribing by Belgian Dentists in Ambulatory Care, from 2010 to 2016. Int. Dent. J. 2019, 69, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.; Al-Mahdi, R.; Malcolm, W.; Palmer, N.; Dahlen, G.; Al-Haroni, M. Comparison of Antimicrobial Prescribing for Dental and Oral Infections in England and Scotland with Norway and Sweden and Their Relative Contribution to National Consumption 2010–2016. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teoh, L.; Stewart, K.; Marino, R.; McCullough, M. Current Prescribing Trends of Antibiotics by Dentists in Australia from 2013 to 2016. Part 1. Dent. J. 2018, 63, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruyndonckx, R.; Coenen, S.; Hens, N.; Vandael, E.; Catry, B.; Goossens, H. Antibiotic Use and Resistance in Belgium: The Impact of Two Decades of Multi-Faceted Campaigning. Acta Clin. Belg. 2021, 76, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, B.; Cederlund, A.; Hultin, M.; Lundgren, F. Effect of Governmental Strategies on Antibiotic Prescription in Dentistry. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2020, 78, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, L.; Stewart, K.; Marino, R.J.; McCullough, M.J. Improvement of Dental Prescribing Practices Using Education and a Prescribing Tool: A Pilot Intervention Study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săndulescu, O.; Preoțescu, L.L.; Streinu-Cercel, A.; Şahin, G.Ö.; Săndulescu, M. Antibiotic Prescribing in Dental Medicine-Best Practices for Successful Implementation. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Wordley, V.; Thompson, W. How Did COVID-19 Impact on Dental Antibiotic Prescribing across England? Br. Dent. J. 2020, 229, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeh, N.-D.; Babkair, H.; Abu-Hammad, S.; Borzangy, S.; Abu-Hammad, A.; Abu-Hammad, O. COVID-19: Present and Future Challenges for Dental Practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3948–4042, Erratum in Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 4780; Erratum in Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD Index. Available online: https://atcddd.fhi.no/atc_ddd_index/ (accessed on 27 July 2024).

- Hrvatski Zavod za Javno Zdravstvo. Hrvatski Zdravstveno-Statistički Ljetopis za 2020—Tablični Podaci. Available online: https://www.hzjz.hr/hrvatski-zdravstveno-statisticki-ljetopis/hrvatski-zdravstveno-statisticki-ljetopis-za-2020-tablicni-podaci/ (accessed on 27 July 2024).

| Year | Cost (EUR)/Contribution to the National Financial Burden | Number of Overall Issued Prescriptions |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2,108,636.07/(0.46%) | 425,385 |

| 2015 | 1,893,366.23/(0.41%) | 439,737 |

| 2016 | 1,884,353.39/(0.39%) | 459,718 |

| 2017 | 1,766,086.82/(0.35%) | 456,499 |

| 2018 | 1,672,978.25/(0.31%) | 449,683 |

| 2019 | 1,683,357.15/(0.29%) | 451,728 |

| 2020 | 1,751,830.89/(0.28%) | 467,947 |

| 2021 | 1,792,705.64/(0.25%) | 479,427 |

| 2022 | 1,704,723.32/(0.23%) | 466,250 |

| 2023 | 1,737,444.36/(data not available) | 451,513 |

| ATC Generic Name | Number of Antibiotic Prescriptions (Percentage) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| J01CR02 amoxicillin + clavulanic acid | 186,698 (53.92%) | 194,123 (55.12%) | 205,411 (56.42%) | 209,632 (57.67%) | 212,860 (58.77%) | 213,156 (59.67%) | 221,922 (61.27%) | 229,072 (61.84%) | 204,971 (57.43%) | 217,162 (63.17%) |

| J01FF01 clindamycin | 44,805 (12.94%) | 45,391 (12.89%) | 46,362 (12.73%) | 44,544 (12.25%) | 43,696 (12.06%) | 43,049 (12.05%) | 44,333 (12.24%) | 43,602 (11.77%) | 48,498 (13.59%) | 46,005 (13.38%) |

| J01CA04 amoxicillin | 52,492 (15.16%) | 50,863 (14.44%) | 50,349 (13.83%) | 48,077 (13.23%) | 45,714 (12.62%) | 43,184 (12.09%) | 39,796 (10.99%) | 40,260 (10.87%) | 47,004 (13.17%) | 33,544 (9.76%) |

| P01AB01 metronidazole | 33,330 (9.63%) | 35,049 (9.95%) | 36,923 (10.14%) | 37,254 (10.25%) | 38,284 (10.57%) | 38,391 (10.75%) | 35,870 (9.9%) | 37,308 (10.07%) | 35,870 (10.05%) | 28,142 (8.19%) |

| J01FA10 azitromycine | 5311 (1.53%) | 5473 (1.55%) | 5398 (1.48%) | 5767 (1.59%) | 5794 (1.6%) | 5872 (1.64%) | 8181 (2.26%) | 8892 (2.4%) | 8992 (2.52%) | 7887 (2.29%) |

| J01DB01 cephalexin | 18,092 (5.23%) | 16,516 (4.69%) | 15,220 (4.18%) | 13,796 (3.8%) | 11,475 (3.17%) | 9642 (2.7%) | 8631 (2.38%) | 8056 (2.17%) | 8287 (2.32%) | 7519 (2.19%) |

| J01DC02 cefuroxime | 917 (0.26%) | 996 (0.28%) | 1018 (0.28%) | 977 (0.27%) | 1045 (0.29%) | 987 (0.28%) | 795 (0.22%) | 744 (0.2%) | 674 (0.19%) | 742 (0.22%) |

| J01DD08 cefixime | 69 (0.02%) | 62 (0.02%) | 56 (0.02%) | 160 (0.04%) | 244 (0.07%) | 250 (0.07%) | 280 (0.08%) | 275 (0.07%) | 411 (0.12%) | 682 (0.2%) |

| J01FA09 clarithromycin | 541 (0.15%) | 556 (0.15%) | 426 (0.11%) | 563 (0.15%) | 579 (0.15%) | 519 (0.14%) | 533 (0.14%) | 506 (0.13%) | 671 (0.18%) | 628 (0.18%) |

| J01FA01 erithromycin | 1153 (0.33%) | 1146 (0.33%) | 1093 (0.3%) | 969 (0.27%) | 900 (0.25%) | 777 (0.22%) | 682 (0.19%) | 709 (0.19%) | 576 (0.16%) | 529 (0.15%) |

| J01AA02 doxycycline | 642 (0.19%) | 595 (0.17%) | 531 (0.15%) | 574 (0.16%) | 554 (0.15%) | 513 (0.14%) | 492 (0.14%) | 383 (0.1%) | 383 (0.11%) | 295 (0.09%) |

| J01CE02 phenoxymethylpenicillin | 217 (0.06%) | 747 (0.21%) | 816 (0.22%) | 733 (0.2%) | 570 (0.16%) | 460 (0.13%) | 313 (0.09%) | 317 (0.09%) | 219 (0.06%) | 238 (0.07%) |

| J01DD13 cefpodoxime | 1 (0.01%) | 5 (0.01%) | 3 (0.01%) | 4 (0.01%) | 19 (0.01%) | 27 (0.01%) | 38 (0.01%) | 57 (0.02%) | 85 (0.02%) | 123 (0.04%) |

| J01MA02 ciprofloxacin | 97 (0.03%) | 84 (0.02%) | 88 (0.02%) | 88 (0.02%) | 83 (0.02%) | 69 (0.02%) | 56 (0.02%) | 58 (0.02%) | 50 (0.01%) | 81 (0.02%) |

| J01MA06 norfloxacin | 87 (0.03%) | 61 (0.02%) | 70 (0.02%) | 69 (0.02%) | 94 (0.03%) | 81 (0.02%) | 84 (0.02%) | 64 (0.02%) | 70 (0.02%) | 54 (0.02%) |

| J01EE01 sulfamethoxazole + trimethoprim | 386 (0.11%) | 357 (0.1%) | 259 (0.07%) | 230 (0.06%) | 188 (0.05%) | 169 (0.04%) | 134 (0.03%) | 61 (0.01%) | 75 (0.02%) | 45 (0.01%) |

| J01XE01 nitrofurantoin | 23 (0.01%) | 40 (0.02%) | 22 (0.01%) | 27 (0.01%) | 36 (0.01%) | 44 (0.02%) | 47 (0.02%) | 52 (0.02%) | 39 (0.02%) | 33 (0.01%) |

| J01XX01 fosfomycin | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (0.01%) | 16 (0.01%) | 11 (0.01%) | 18 (0.01%) | 19 (0.01%) | 21 (0.01%) | 27 (0.01%) |

| J01MA12 levofloxacin | 6 (0.01%) | 8 (0.01%) | 3 (0.01%) | 3 (0.01%) | 10 (0.01%) | 11 (0.01%) | 6 (0.01%) | 5 (0.01%) | 7 (0.01%) | 9 (0.01%) |

| J01MA14 moxifloxacin | 12 (0.01%) | 6 (0.01%) | 2 (0.01%) | 2 (0.01%) | 7 (0.01%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (0.01%) | 2 (0.01%) | 2 (0.01%) | 5 (0.01%) |

| J01CE10 benzathine phenoxymethylpenicillin | 1341 (0.39%) | 85 (0.02%) | 52 (0.01%) | 12 (0.01%) | 26 (0.01%) | 29 (0.01%) | 13 (0.01%) | 3 (0.01%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| J01DD14 ceftibuten | 5 (0.01%) | 6 (0.01%) | 2 (0.01%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 346,225 (100%) | 352,169 (100%) | 364,104 (100%) | 363,487 (100%) | 362,194 (100%) | 357,241 (100%) | 362,231 (100%) | 370,445 (100%) | 356,905 (100%) | 343,750 (100%) |

| ATC Generic Name | DID 2014 | DID 2015 | DID 2016 | DID 2017 | DID 2018 | DID 2019 | DID 2020 | DID 2021 | DID 2022 | DID 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J01AA02 doxycycline | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.01 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.005 |

| J01CA04 amoxicillin | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.174 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.185 | 0.14 |

| J01CE02 phenoxymethylpenicillin | 0.0025 | 0.0013 | 0.0014 | 0.0012 | 0.001 | 0.0008 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | 0.0004 | 0.0004 |

| J01CR02 amoxicillin + clavulanic acid | 1.15 | 1.22 | 1.28 | 1.3 | 1.36 | 1.38 | 1.47 | 1.54 | 1.39 | 1.47 |

| J01DB01 cephalexin | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.031 | 0.029 | 0.028 | 0.029 | 0.026 |

| J01DC02 cefuroxime | 0.0056 | 0.006 | 0.0062 | 0.0063 | 0.0065 | 0.0062 | 0.005 | 0.0048 | 0.0043 | 0.0049 |

| J01DD08 cefixime | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0006 | 0.0009 | 0.0009 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.0016 | 0.0025 |

| J01DD13 cefpodoxime | 0 | 0.00002 | 0.00001 | 0.00002 | 0.00004 | 0.00008 | 0.0001 | 0.00017 | 0.00028 | 0.0004 |

| J01EE01 sulfamethoxazole + trimethoprim | 0.0058 | 0.0054 | 0.0039 | 0.0035 | 0.0026 | 0.0025 | 0.002 | 0.0009 | 0.001 | 0.0008 |

| J01FA01 erithromycin | 0.0038 | 0.0039 | 0.0037 | 0.0035 | 0.0032 | 0.0028 | 0.0027 | 0.0027 | 0.0021 | 0.0021 |

| J01FA09 clarithromycin | 0.0044 | 0.0046 | 0.0034 | 0.0046 | 0.0048 | 0.0043 | 0.0044 | 0.0044 | 0.0057 | 0.0053 |

| J01FA10 azitromycin | 0.01 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.02 | 0.021 | 0.018 |

| J01FF01 clindamycin | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.128 | 0.138 | 0.136 | 0.154 | 0.145 |

| J01MA02 ciprofloxacin | 0.0004 | 0.0004 | 0.00039 | 0.00039 | 0.00035 | 0.0003 | 0.00025 | 0.00026 | 0.00023 | 0.0004 |

| J01MA06 norfloxacin | 0.00066 | 0.00043 | 0.00055 | 0.00059 | 0.0008 | 0.0007 | 0.00068 | 0.00056 | 0.00062 | 0.00044 |

| J01MA12 levofloxacin | 0.000058 | 0.000026 | 0.000028 | 0.00002 | 0.000087 | 0.0001 | 0.000047 | 0.000056 | 0.000056 | 0.000064 |

| J01MA14 moxifloxacin | 0.000067 | 0.000027 | 0.000009 | 0.000009 | 0.00006 | 0 | 0.000056 | 0.000019 | 0.000014 | 0.000025 |

| P01AB01 metronidazole | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.082 | 0.085 | 0.081 | 0.079 | 0.062 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Šutej, I.; Bašić, K.; Šegović, S.; Peroš, K. Antibiotic Prescribing Trends in Dentistry during Ten Years’ Period—Croatian National Study. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13090873

Šutej I, Bašić K, Šegović S, Peroš K. Antibiotic Prescribing Trends in Dentistry during Ten Years’ Period—Croatian National Study. Antibiotics. 2024; 13(9):873. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13090873

Chicago/Turabian StyleŠutej, Ivana, Krešimir Bašić, Sanja Šegović, and Kristina Peroš. 2024. "Antibiotic Prescribing Trends in Dentistry during Ten Years’ Period—Croatian National Study" Antibiotics 13, no. 9: 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13090873

APA StyleŠutej, I., Bašić, K., Šegović, S., & Peroš, K. (2024). Antibiotic Prescribing Trends in Dentistry during Ten Years’ Period—Croatian National Study. Antibiotics, 13(9), 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13090873